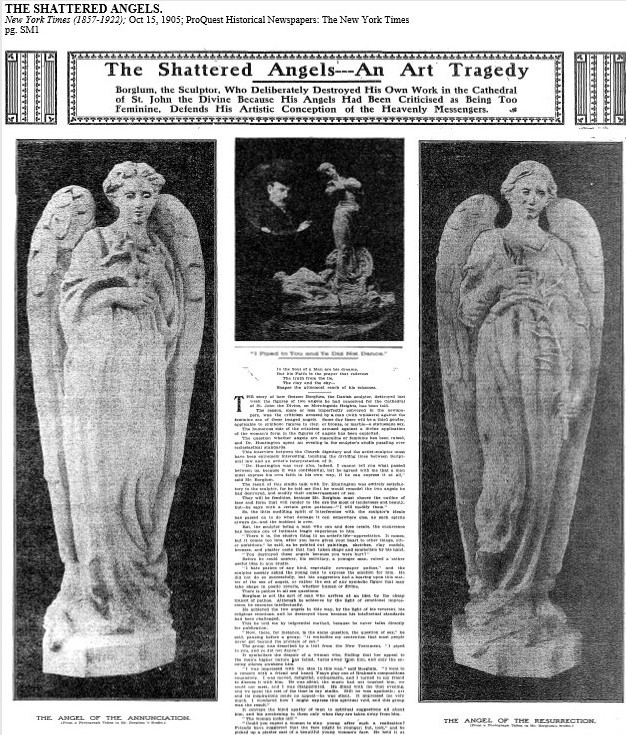

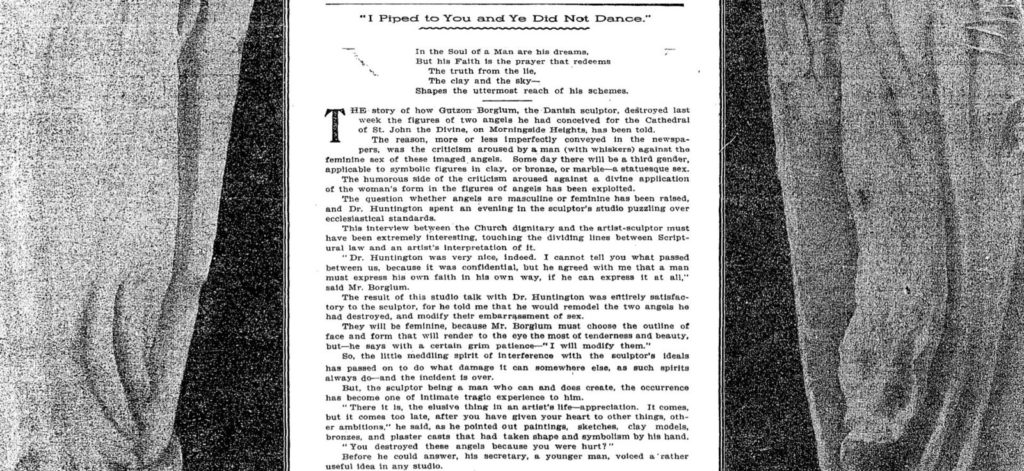

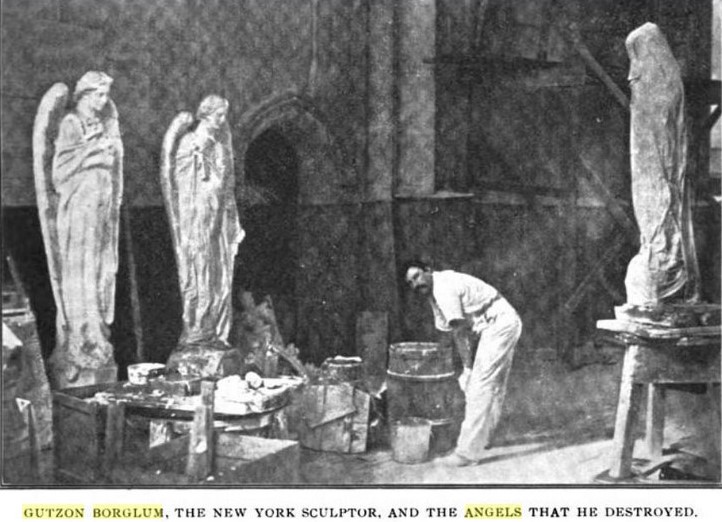

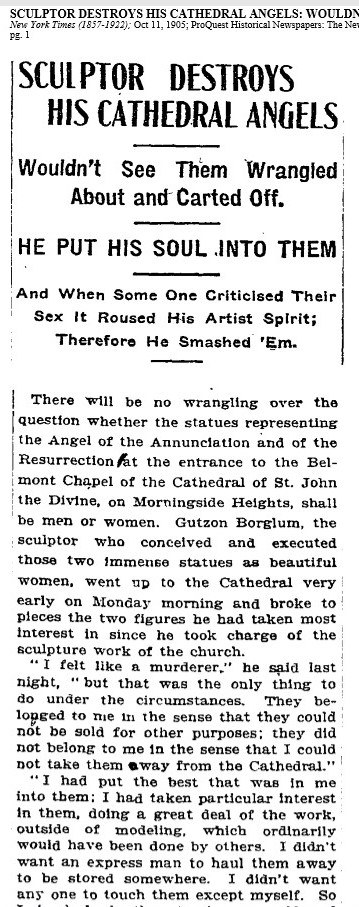

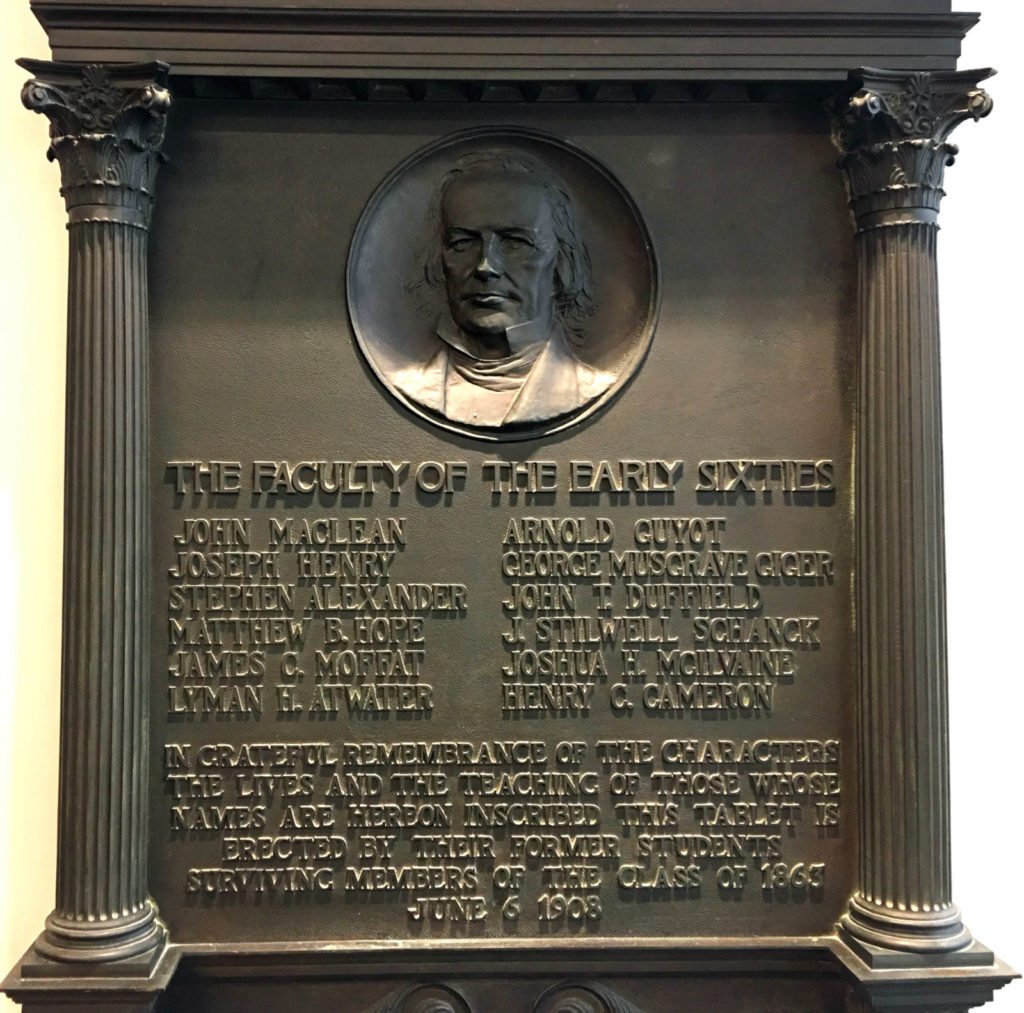

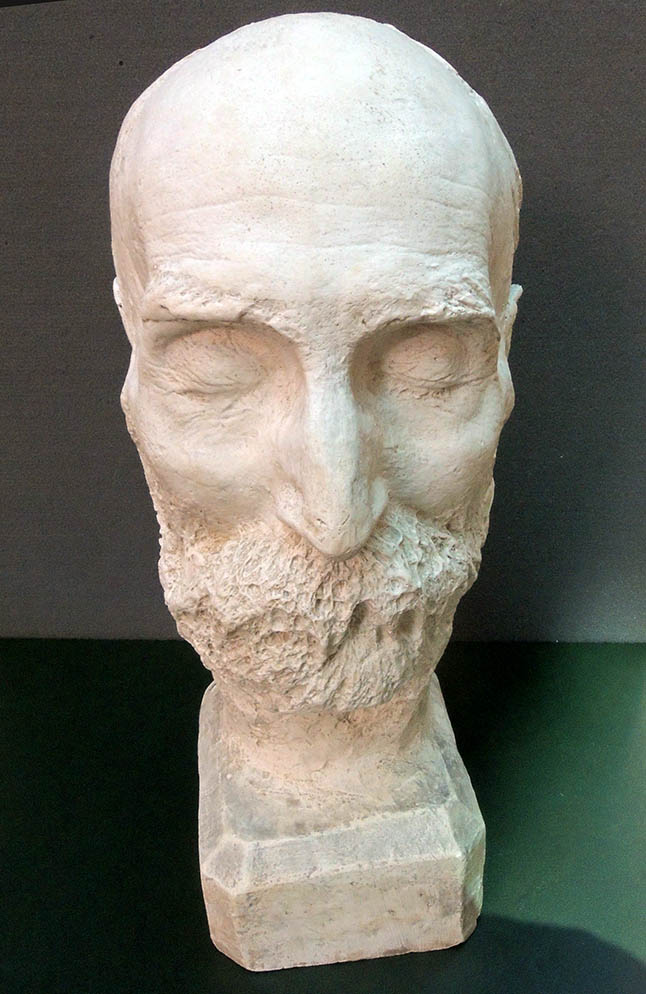

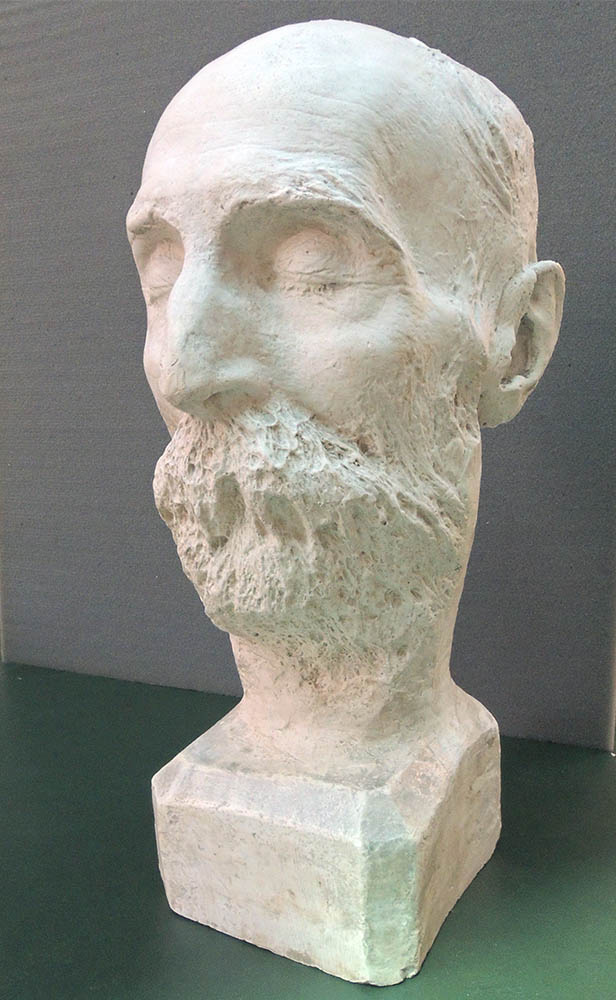

Not long after John Gutzon de la Mothe Borglum (1867-1941, famous for carving Mount Rushmore) finished sculpting dozens of gargoyles for Princeton University’s Class of 1879 Hall at the request of his friend Woodrow Wilson, Borglum was commissioned to sculpt a series of angels for the Cathedral of St. John the Divine. As the project neared completion, Catholic officials were surprised to find many of his angels were female. This led to a heated public debate over the gender of angels, repeated in newspaper across the country.

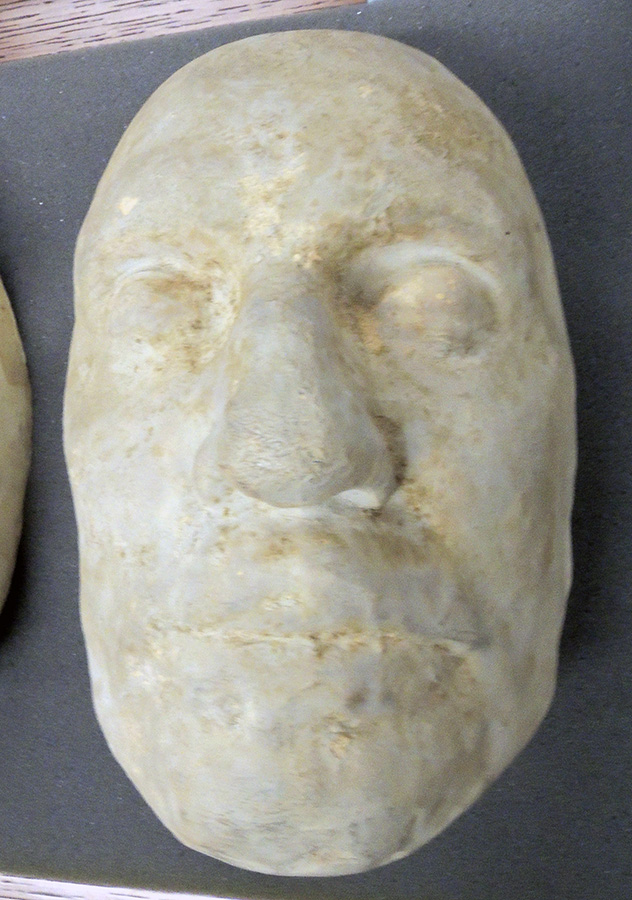

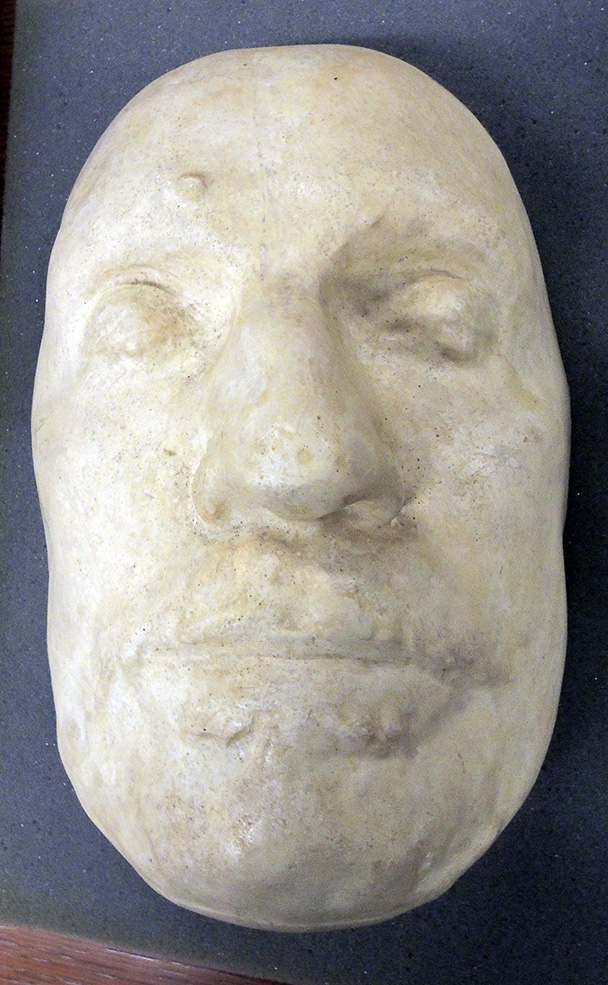

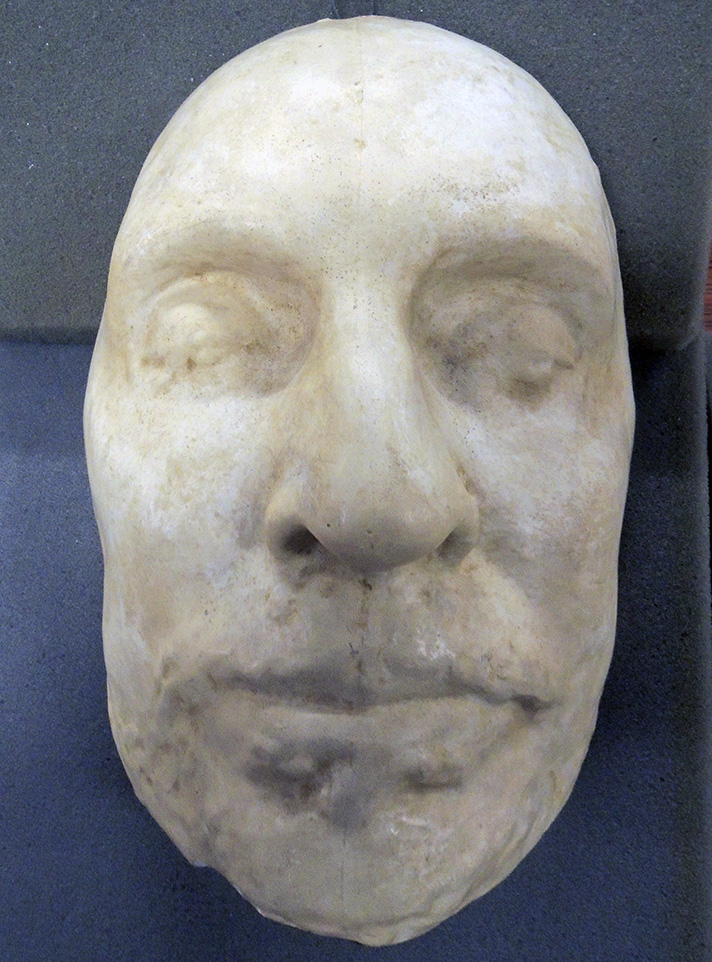

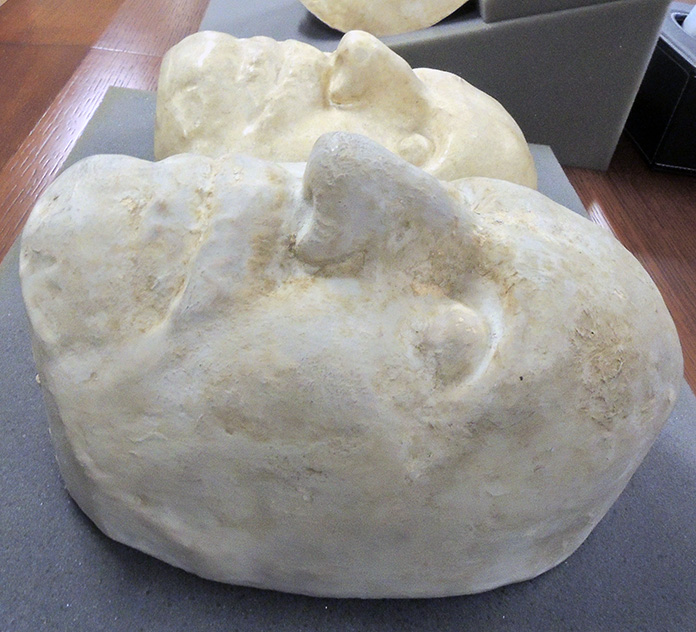

Borglum was told to replace the female angels. An impassioned dialogue followed, ending with the artist smashing the molds for several of the figures. “I felt like a murderer,” he confessed afterward, “but that was the only thing to do under the circumstances.” –“The Sex of Angels,” Current Opinion, Volume 39 (1905). Eventually Borglum sculpted new molds and then, publicly declared they were poorly cast and did not want his name connected with them.

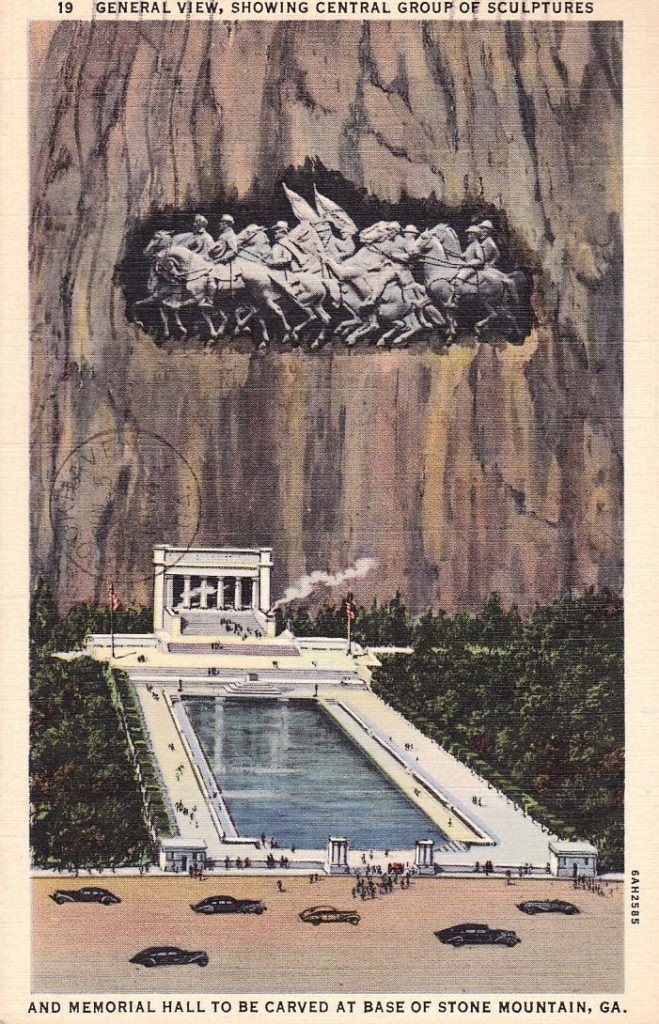

The controversy led to enormous publicity, national fame for the sculptor, and in 1910, Woodrow Wilson presented Borglum with an honorary master’s degree for service to the University. His next major commission was to carve relief statues of Robert E. Lee, Stonewall Jackson, and Jefferson Davis on the Stone Mountain, hired by the United Daughters of the Confederacy. Originally the frieze was to include an altar to the Ku Klux Klan but this plan was later dropped (See the Stone Mountain Sculpture and Memorial Hall as originally projected on the left).

The controversy led to enormous publicity, national fame for the sculptor, and in 1910, Woodrow Wilson presented Borglum with an honorary master’s degree for service to the University. His next major commission was to carve relief statues of Robert E. Lee, Stonewall Jackson, and Jefferson Davis on the Stone Mountain, hired by the United Daughters of the Confederacy. Originally the frieze was to include an altar to the Ku Klux Klan but this plan was later dropped (See the Stone Mountain Sculpture and Memorial Hall as originally projected on the left).

In 1925, when a dispute arose between Borglum and the managing association. the sculptor once again smashed the models he had completed. He quickly moved on to begin the carving of the famous Mount Rushmore quartet.

For more, read: “The Sordid History of Mount Rushmore: The sculptor behind the American landmark had some unseemly ties to white supremacy groups” by Matthew Shaer in Smithsonian Magazine October 2016. Also recommended: Debra McKinney, “Stone Mountain: A Monumental Dilemma: Some see the monument as “the largest shrine to white supremacy in the history of the world.” Intelligence Report, Southern Poverty Law Center, Spring 2018. https://www.splcenter.org/fighting-hate/intelligence-report/2018/stone-mountain-monumental-dilemma

In 1924, the National Alumni Committee of Princeton donated $1,000 to support the project.

“In the early going,” writes John Taliaferro, “the Klan contributed money directly to the Stone Mountain Confederate Monumental Association, a number of whose members were active Klansmen. While there seems to be no extant proof that Borglum officially joined the Klan himself—that he took the secret oath or donned a hooded robe—he nonetheless became deeply involved in Klan politics, as they related to Stone Mountain and on a national scale as well. He attended Klan rallies, served on Klan committees, and endeavored to play peacemaker in several Klan leadership disputes (with mixed results).

… The Kloran, the Klan’s book of rules, demanded that members be native born, white, male, and Gentile. And after World War I, the Klan’s Kreed became increasingly white supremacist, anti-Catholic, anti-Semitic, anti-labor, anti-alien.” — John Taliaferro, Great White Fathers: The Story of the Obsessive Quest to Create Mount Rushmore (2007).

It is perhaps ironic that a scandal emerged within the Klan leadership when they found out Borglum was a Catholic.