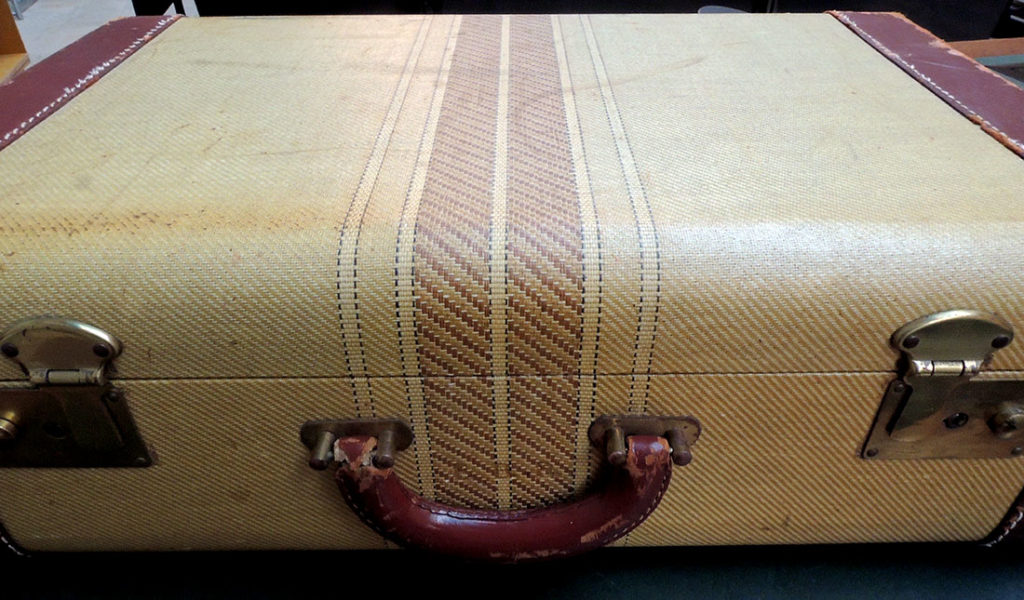

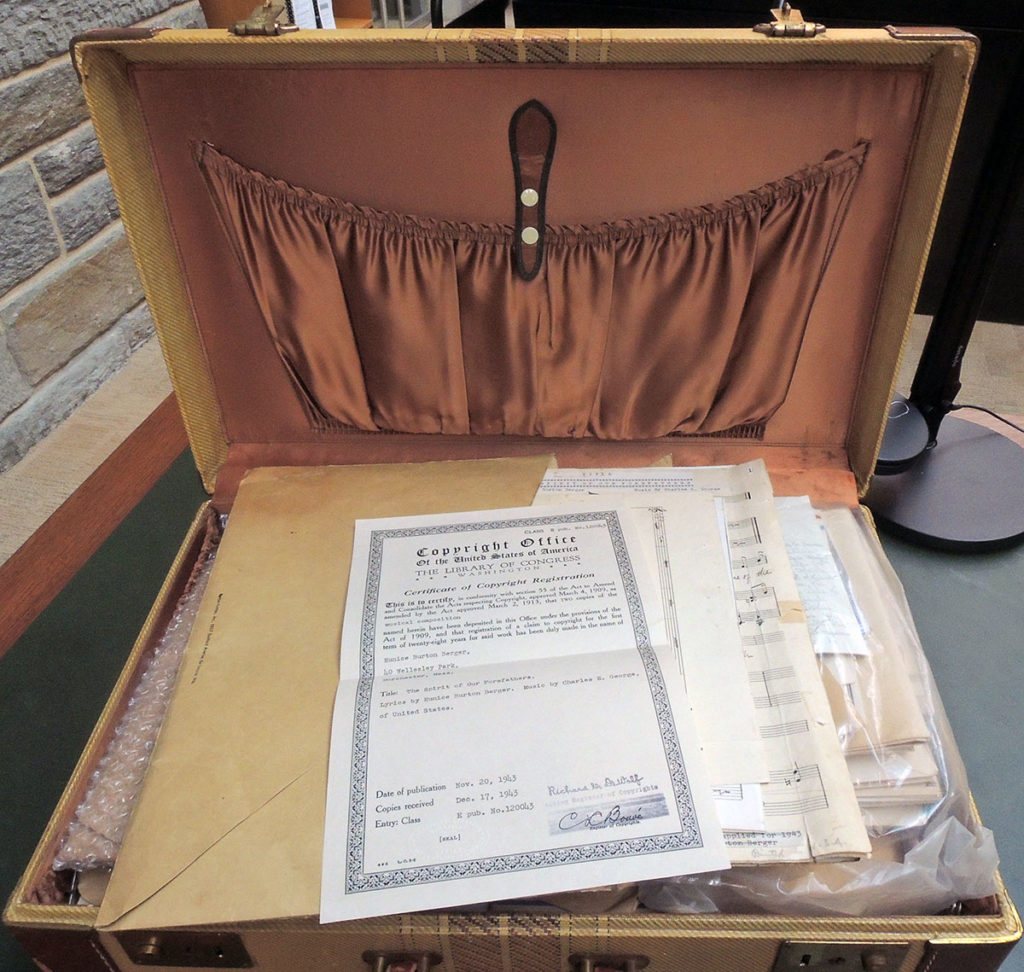

When an author finishes a book or a poem, she sends the text off to a publisher. When a painter finishes an oil painting, it is hung in a gallery so buyers can see and hopefully, buy it. What happens to a composer who writes music for a marching band? How do you print the 35 parts and have them distributed to be copyrighted and played? The Graphic Arts Collection recently acquired a suitcase filled with the printing plates, proof sheets, and published music by Eunice Burton Berger (ca.1888-1966), a Dorchester, Massachusetts musician who did just that. Together with her husband, Louis H. Berger (1879-1965), an engineering and surveying instrument manufacturer, Berger wrote, printed, promoted, and sold her music to radio programs, military bands, and national music companies.

When an author finishes a book or a poem, she sends the text off to a publisher. When a painter finishes an oil painting, it is hung in a gallery so buyers can see and hopefully, buy it. What happens to a composer who writes music for a marching band? How do you print the 35 parts and have them distributed to be copyrighted and played? The Graphic Arts Collection recently acquired a suitcase filled with the printing plates, proof sheets, and published music by Eunice Burton Berger (ca.1888-1966), a Dorchester, Massachusetts musician who did just that. Together with her husband, Louis H. Berger (1879-1965), an engineering and surveying instrument manufacturer, Berger wrote, printed, promoted, and sold her music to radio programs, military bands, and national music companies.

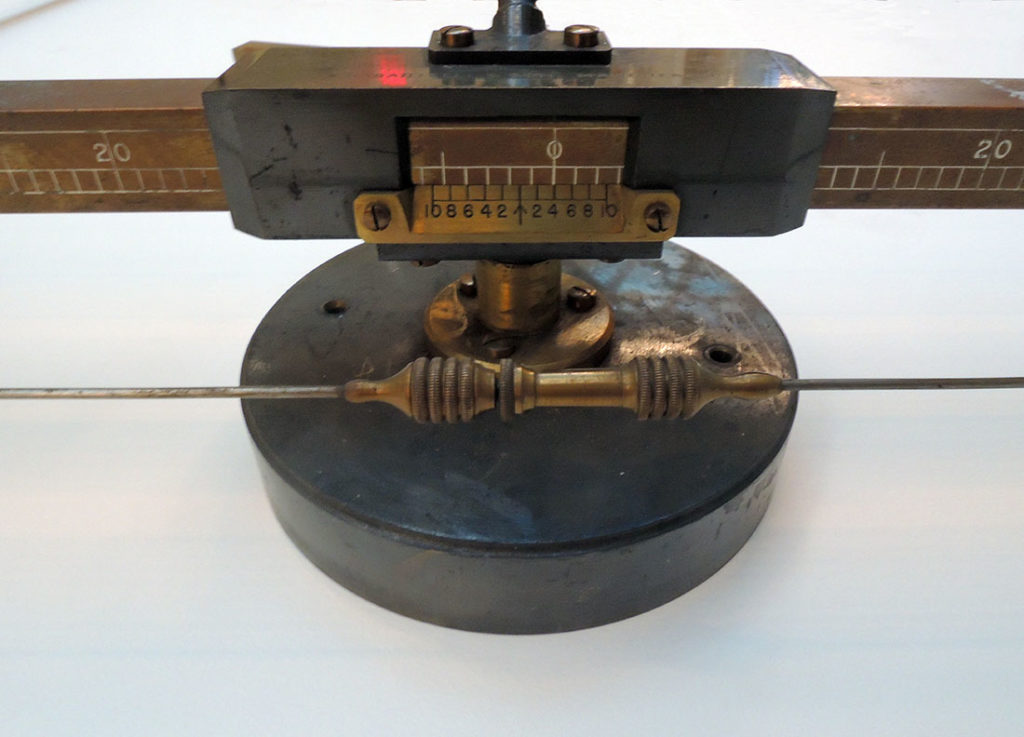

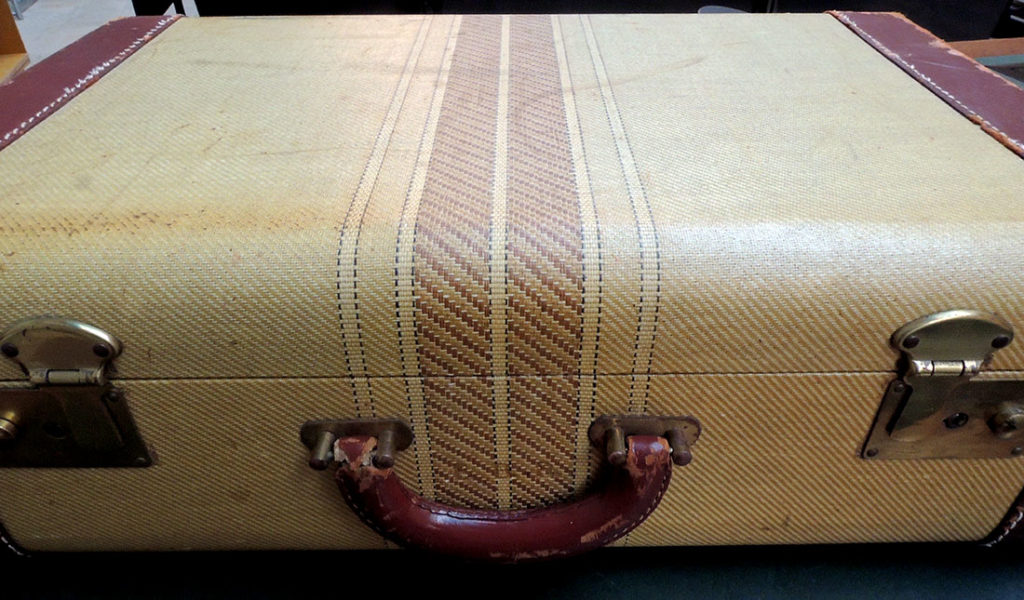

Note the initials, E.B.B. by the handle.

Note the initials, E.B.B. by the handle.

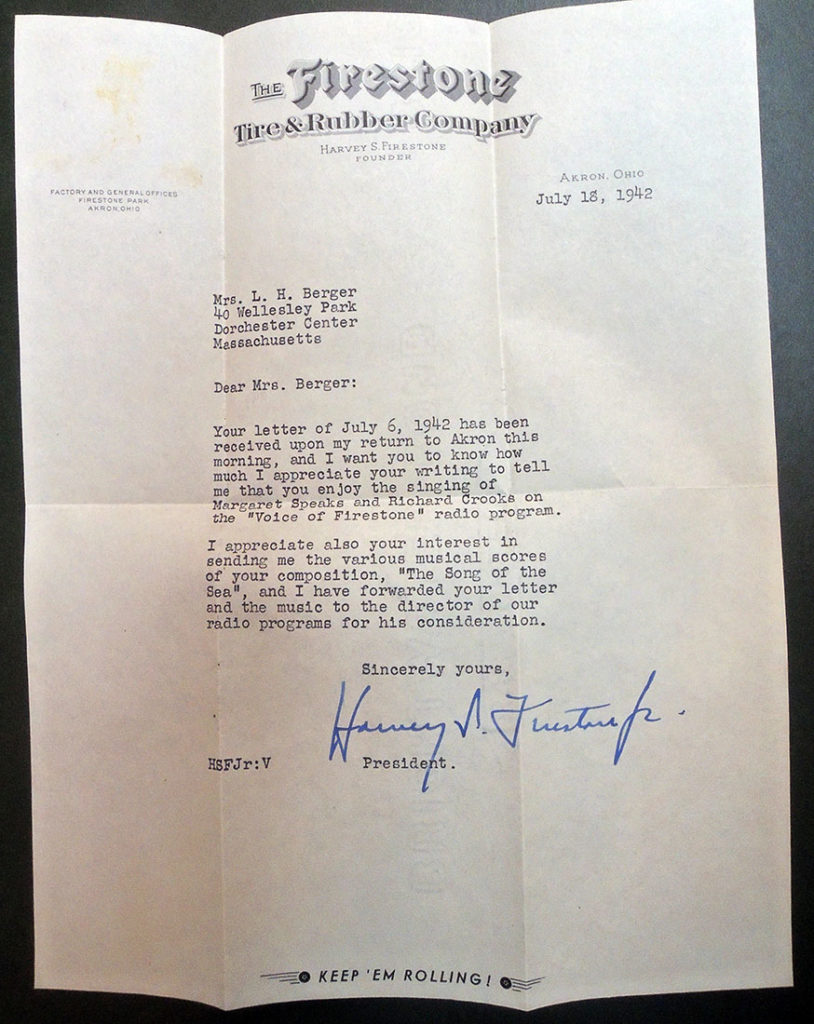

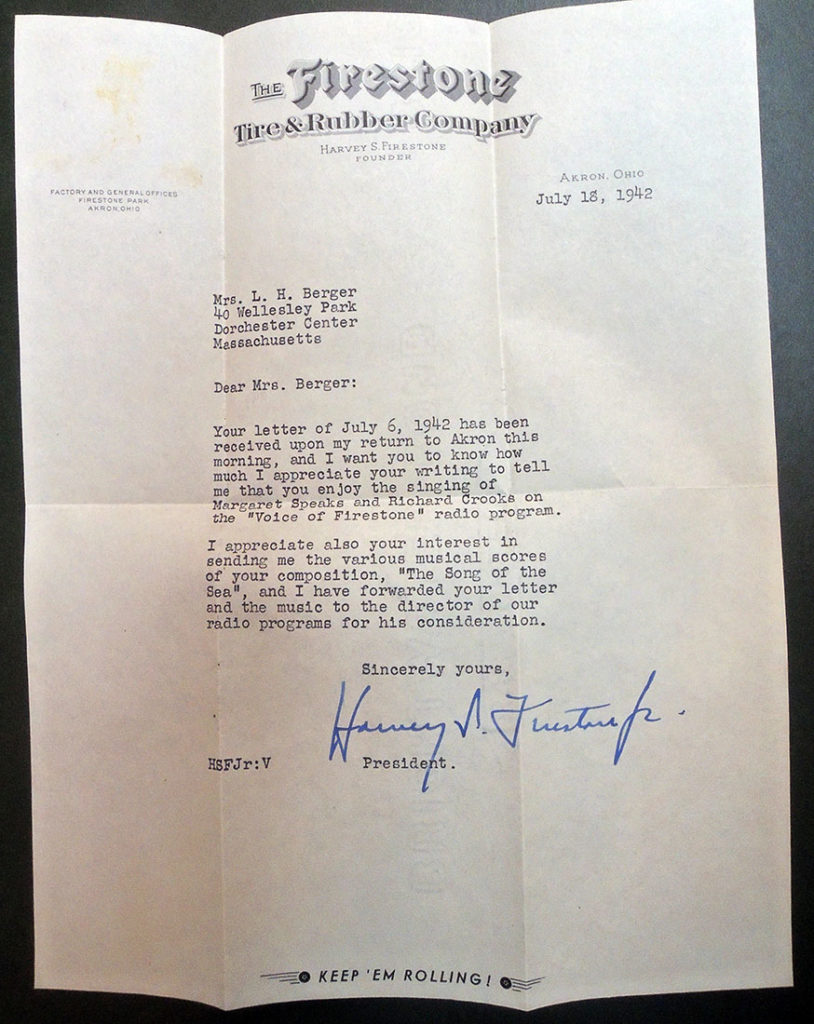

One of many examples of her self-promotion is a reply she received from Harvey S. Firestone Jr., Princeton University class of 1920 (1898-1973) and son of Harvey S. Firestone (1868-1938), in whose memory Princeton University’s Firestone Library is named. In addition to managing the Firestone Tire and Rubber Company, both father and son sponsored The Voice of Firestone (originally called The Firestone Hour), a radio broadcast on NBC Radio beginning on December 3, 1928, featuring classical musicians and popular Broadway stars. The show later became the first series to be simulcast on both radio and television, and Harvey Jr. actively managed both the radio and television programs. [Broadcasts archived https://necmusic.edu/archives/voice-of-firestone] It is unknown whether Berger’s music was ever included in one of the Firestone broadcasts.

It is unknown whether Berger’s music was ever included in one of the Firestone broadcasts.

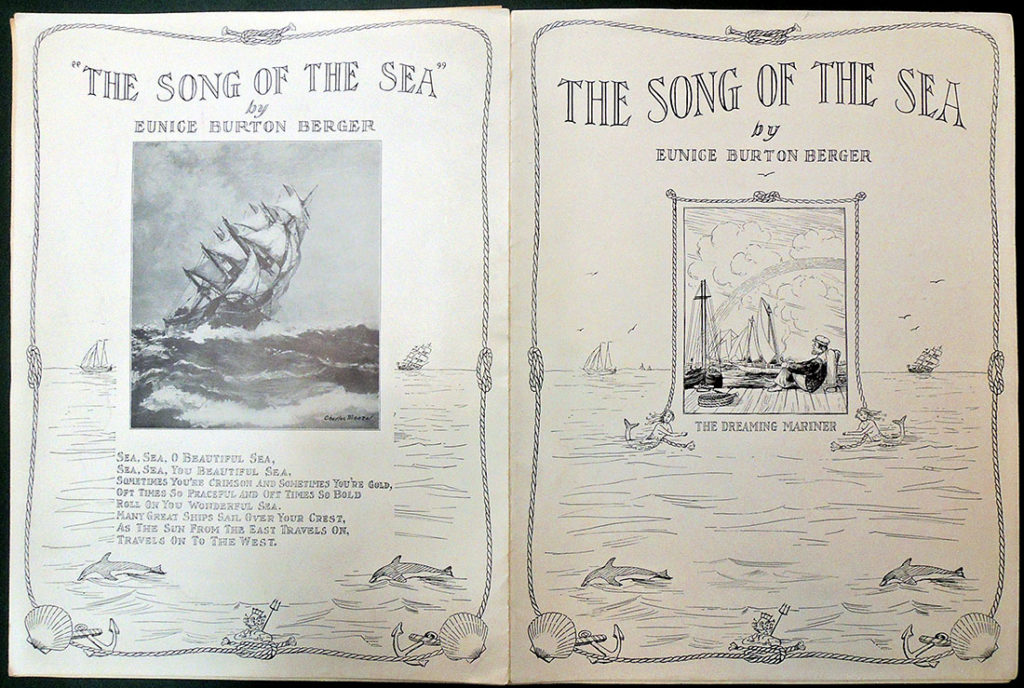

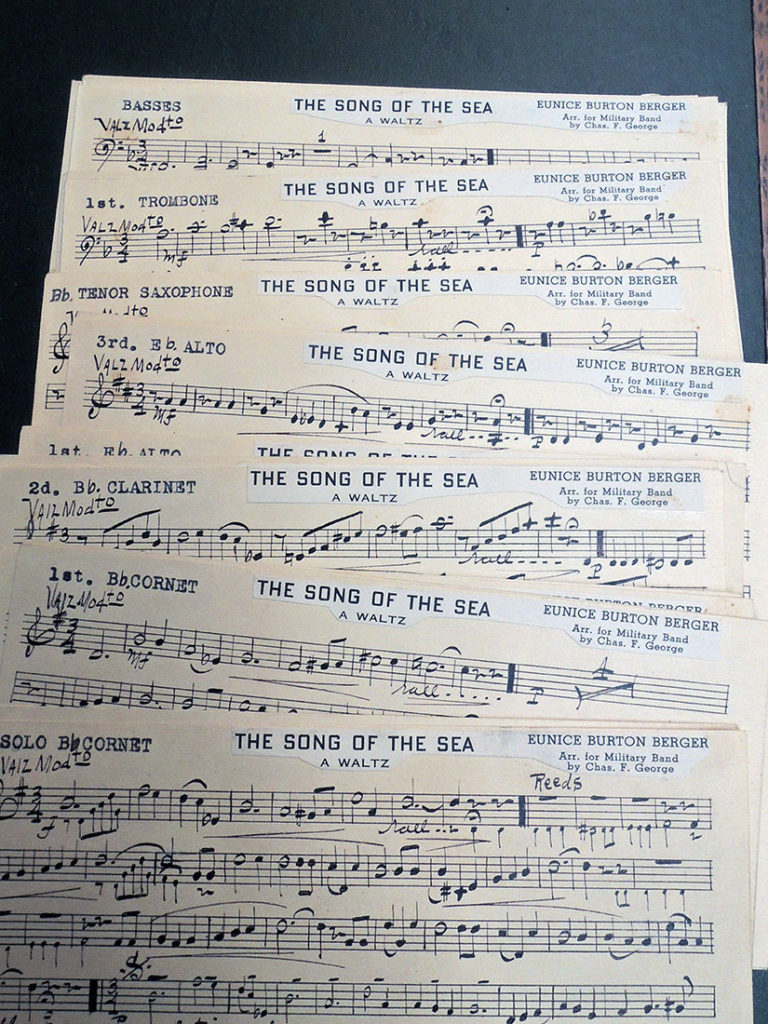

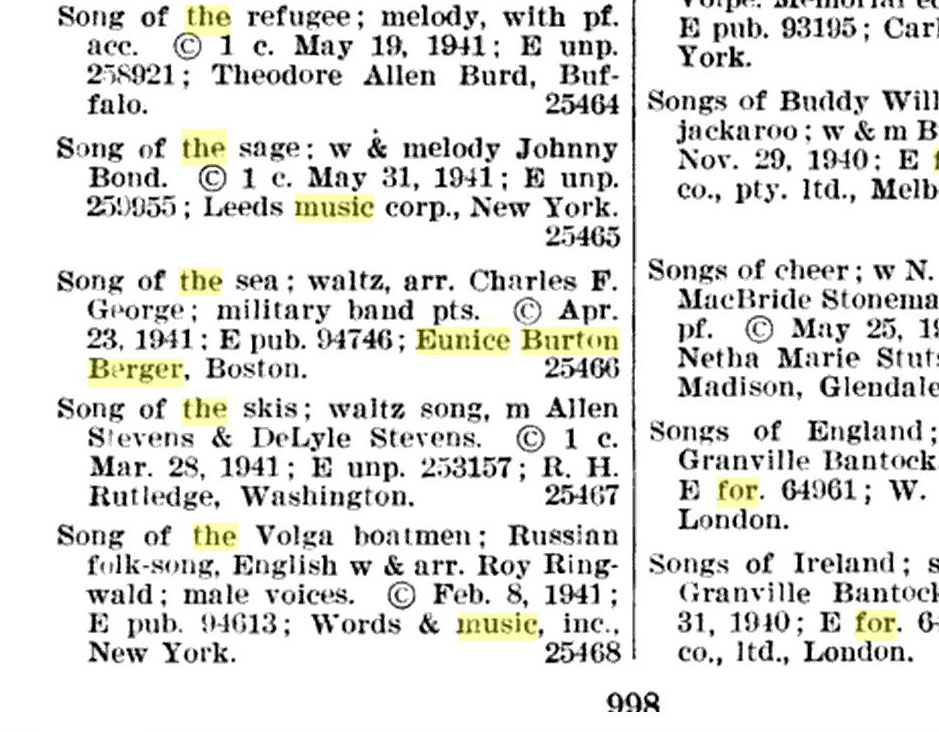

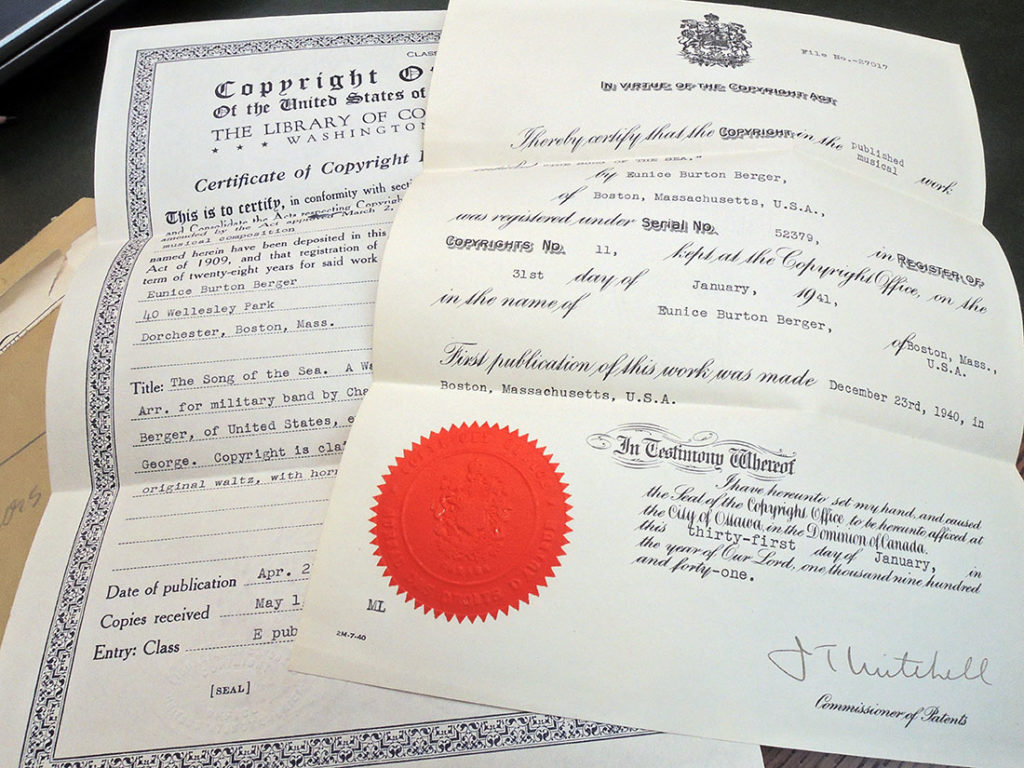

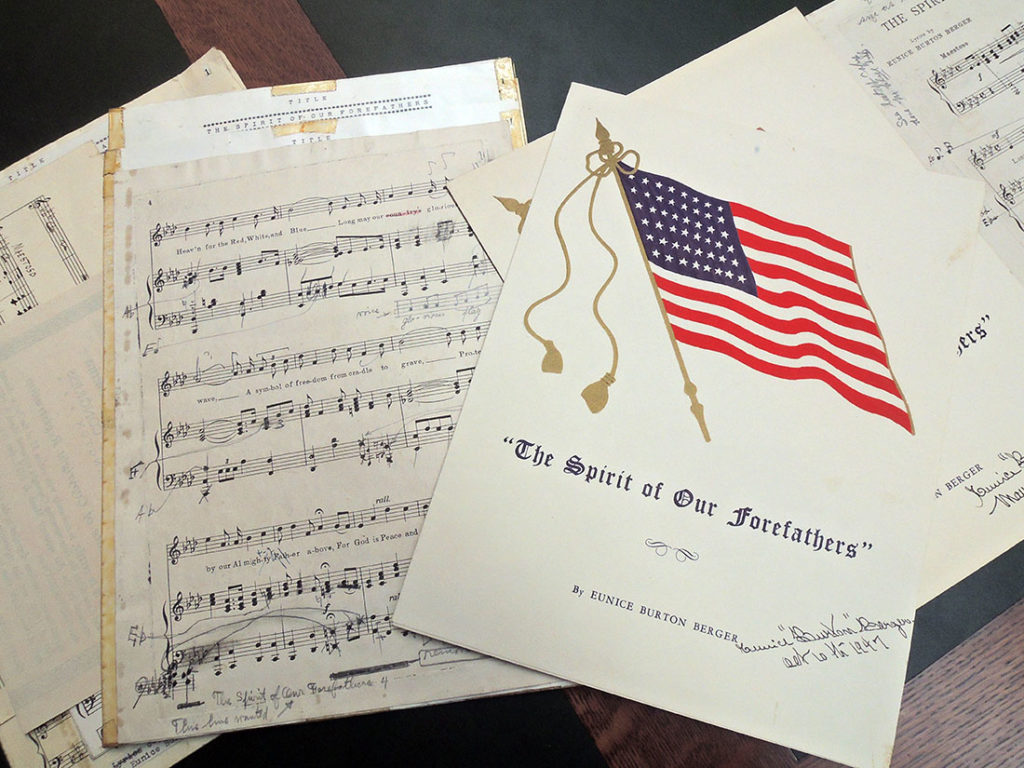

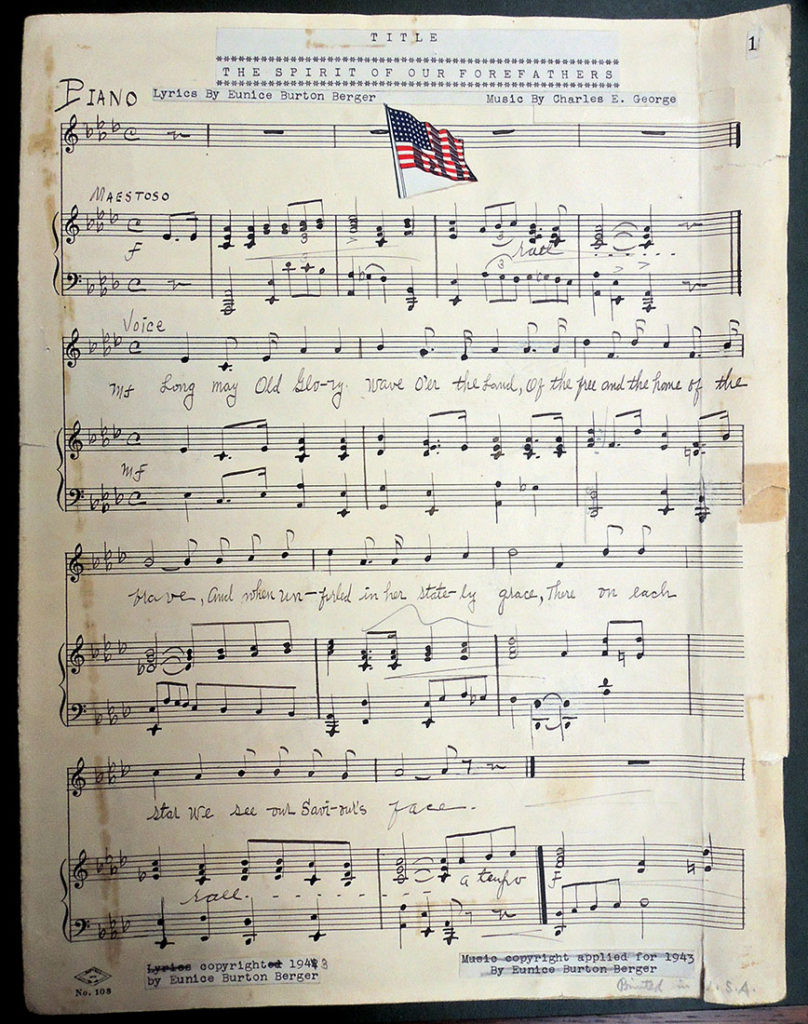

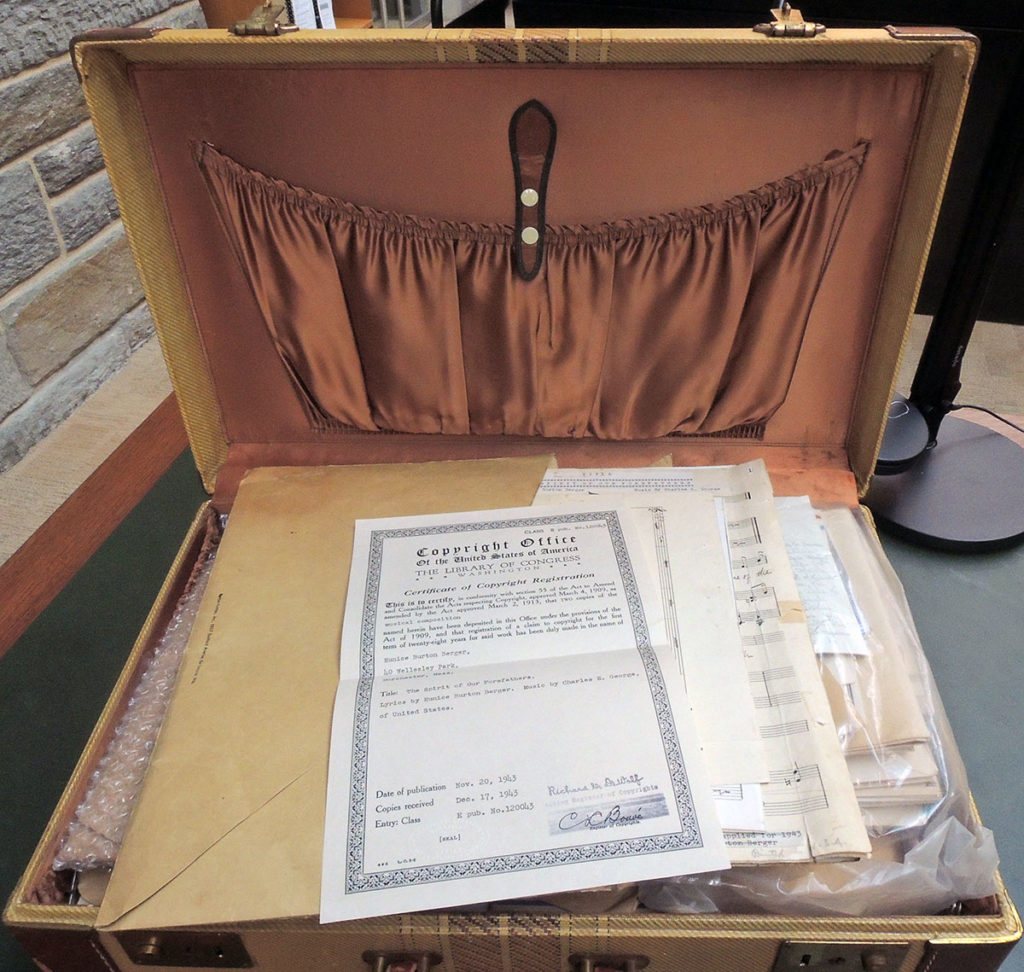

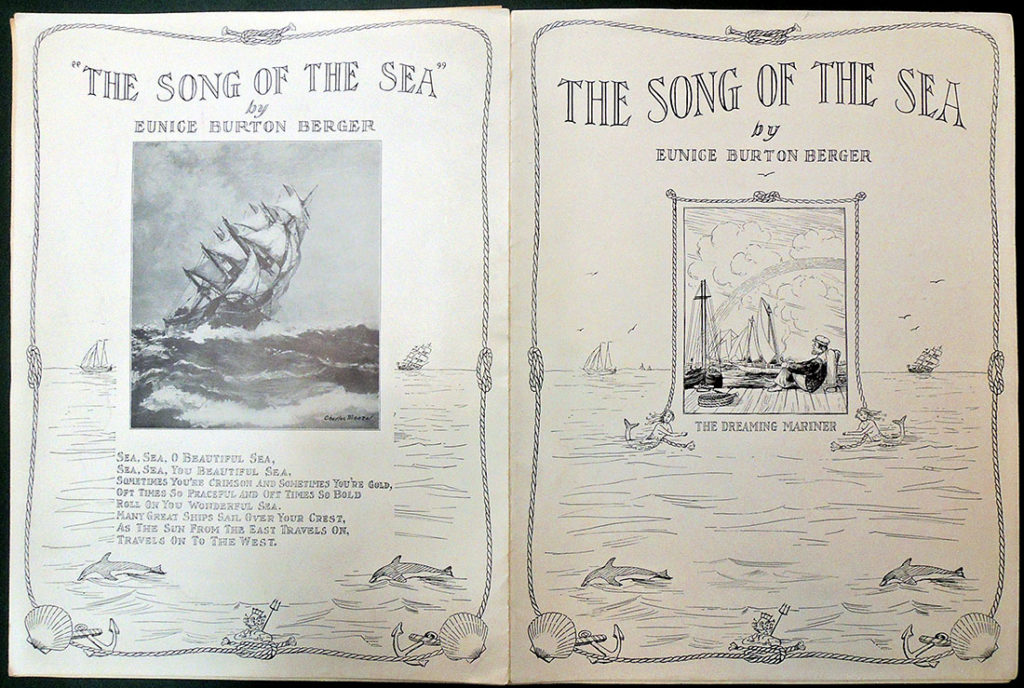

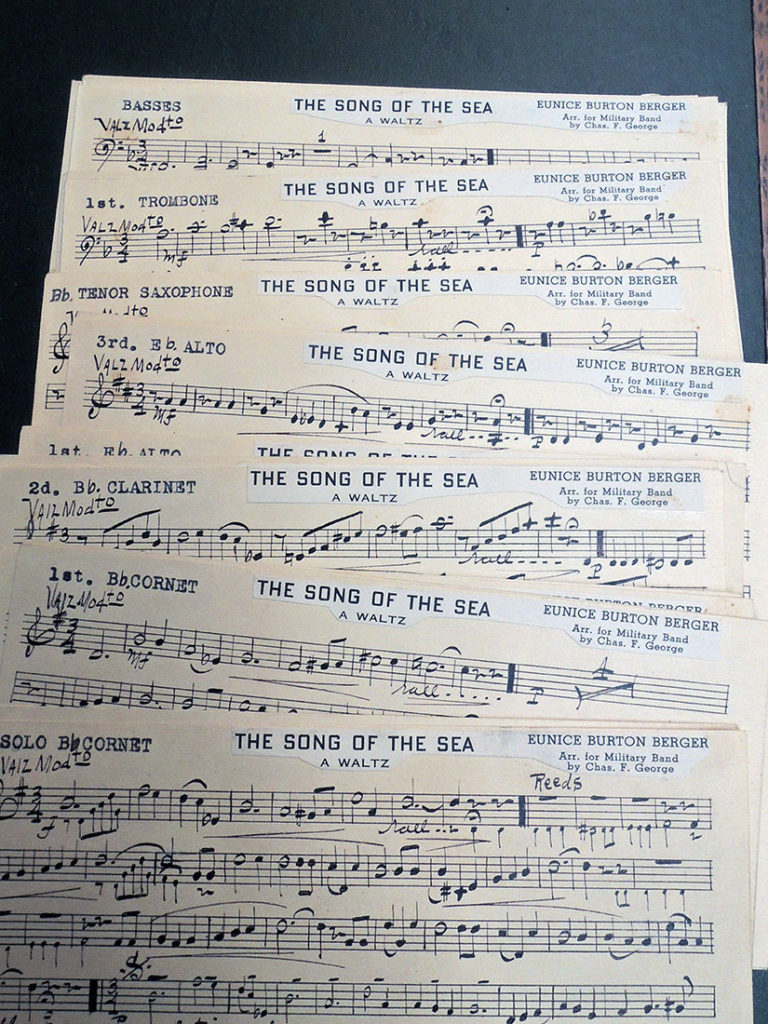

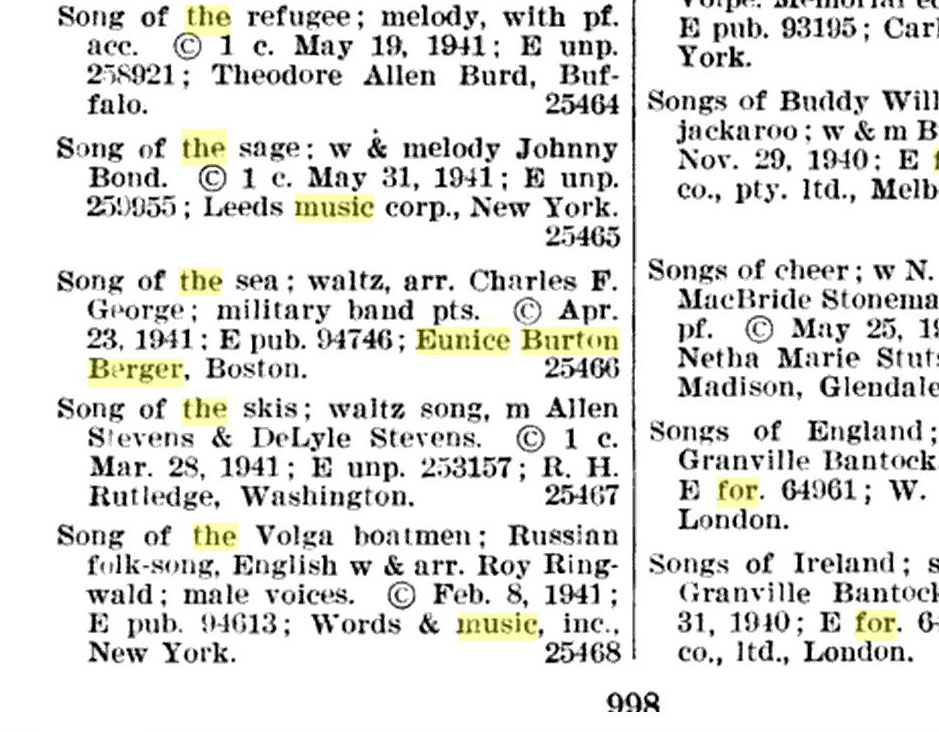

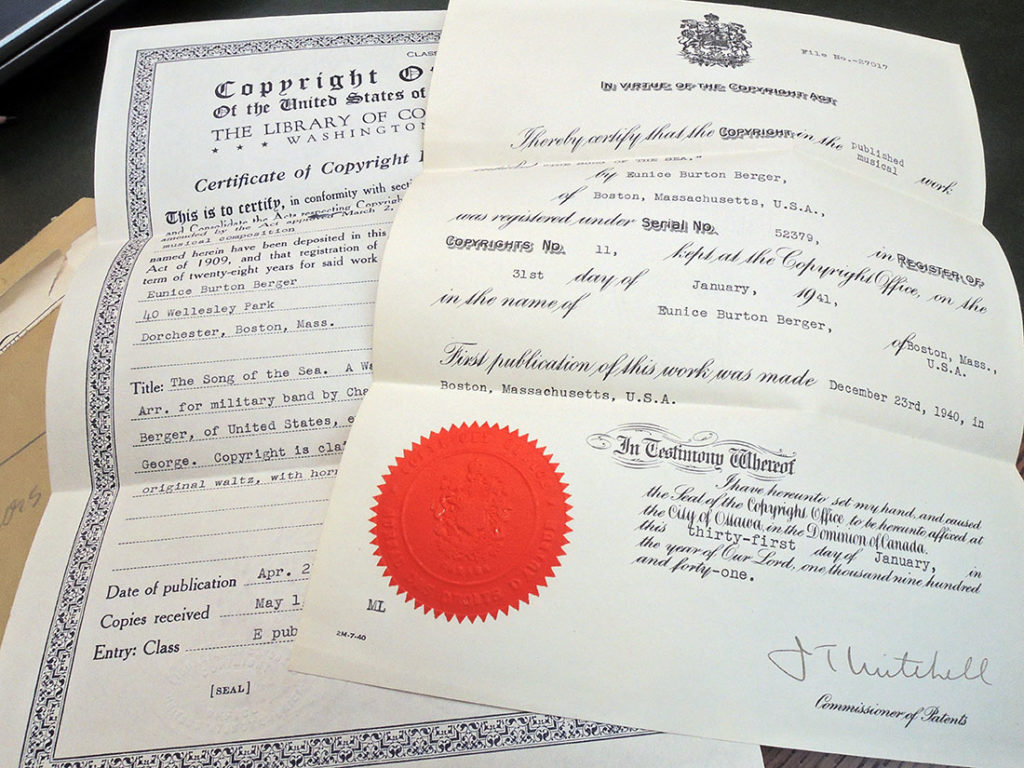

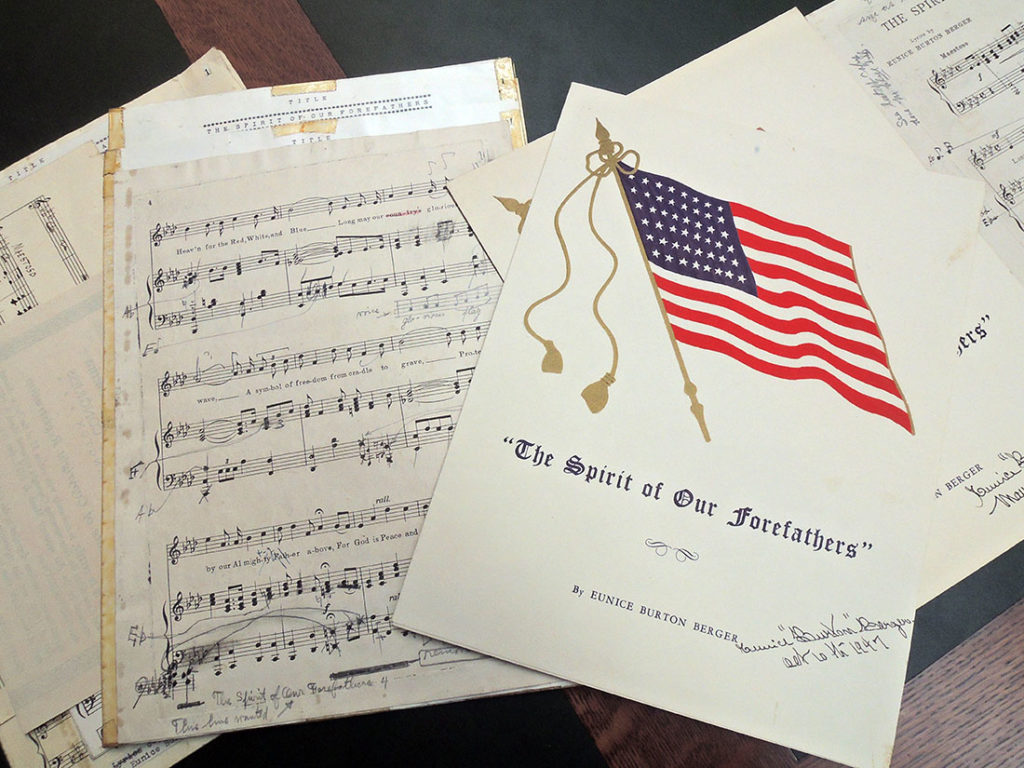

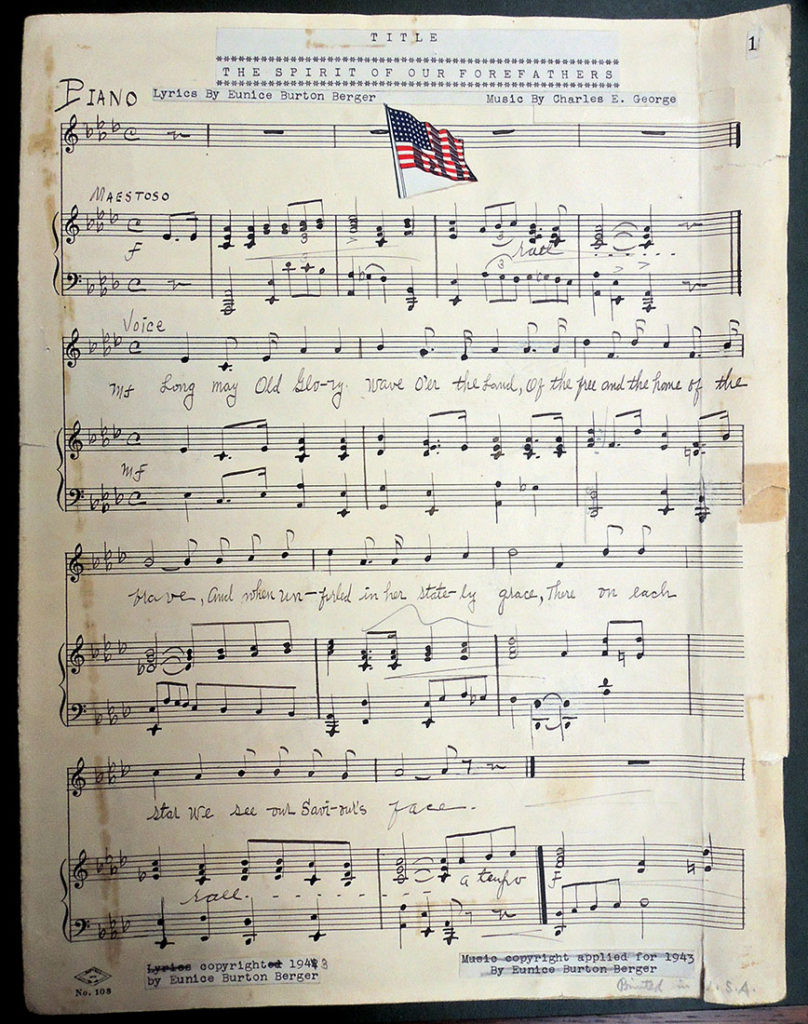

Berger’s compositions include: “On the Brink,” “The Song of the Sea,” “The Spirit of Our Forefathers,” all copyrighted by her between 1939 and 1943, plus “Men of the Sea,” copyrighted in 1960. A few additional poems and partially completed musical scores are also found in her suitcase, along with correspondence between Berger and various members of the branches of the service thanking her for sending her scores. Copyright notices and certificates from the Library of Congress are present for each of her compositions along with paste-ups and proof at each stage of the printing process. There are contracts for royalties and research on the art to be included on the sheet music.

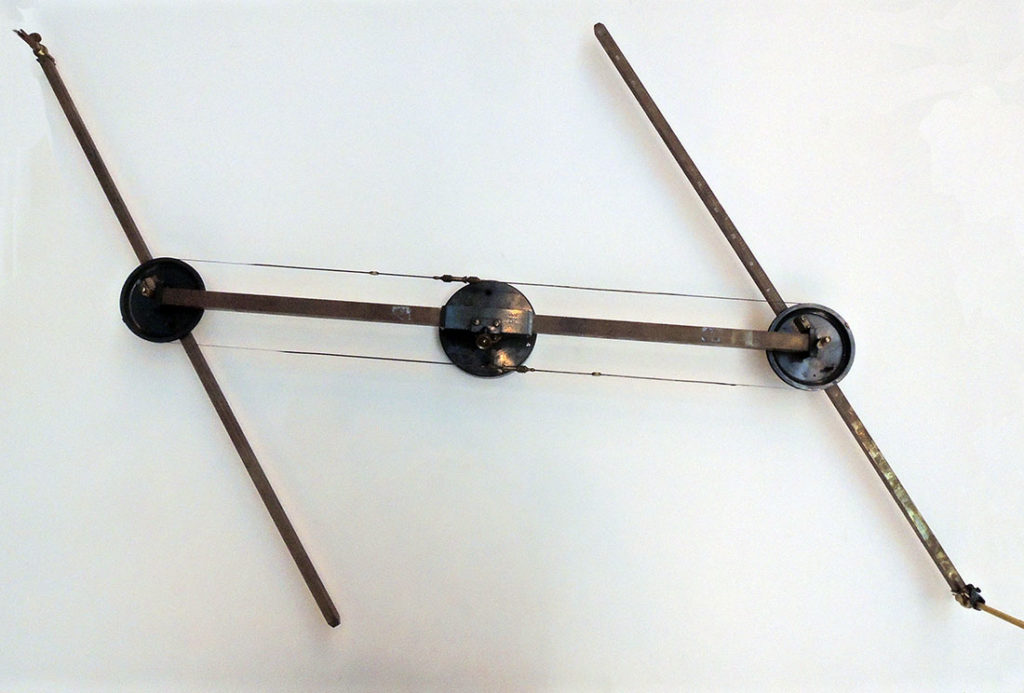

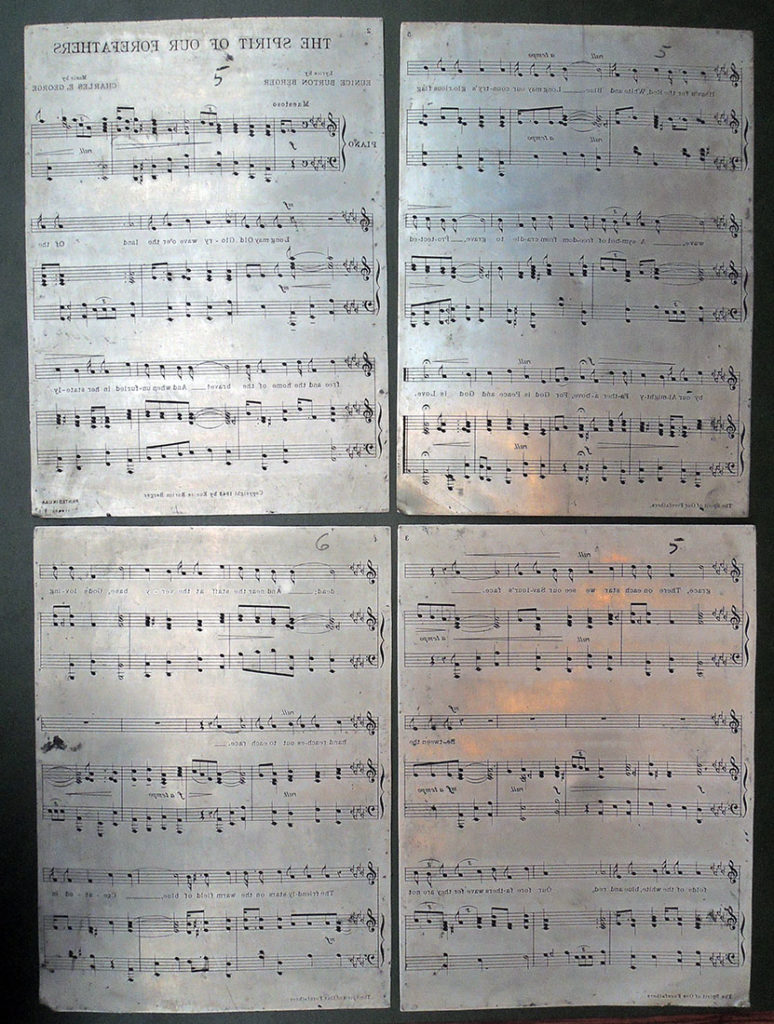

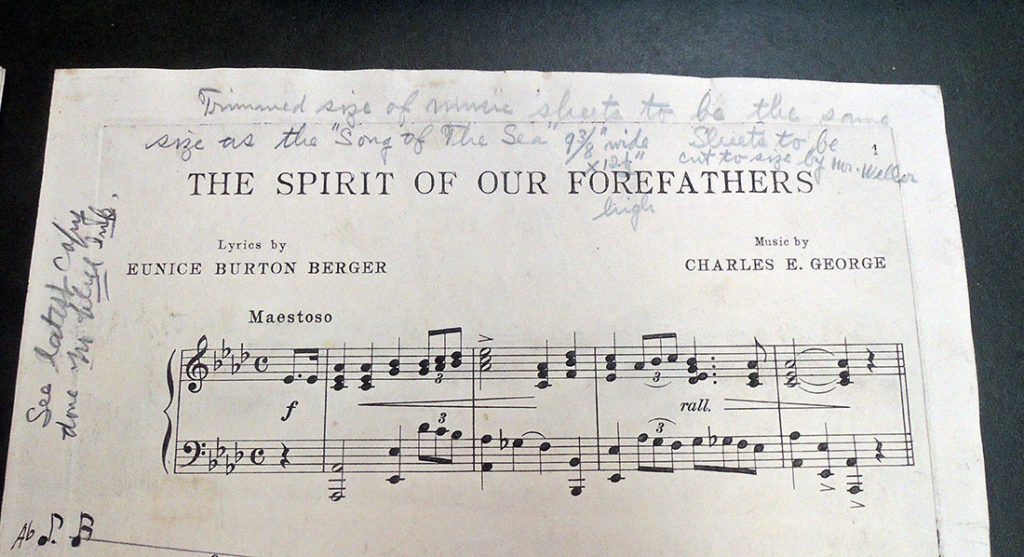

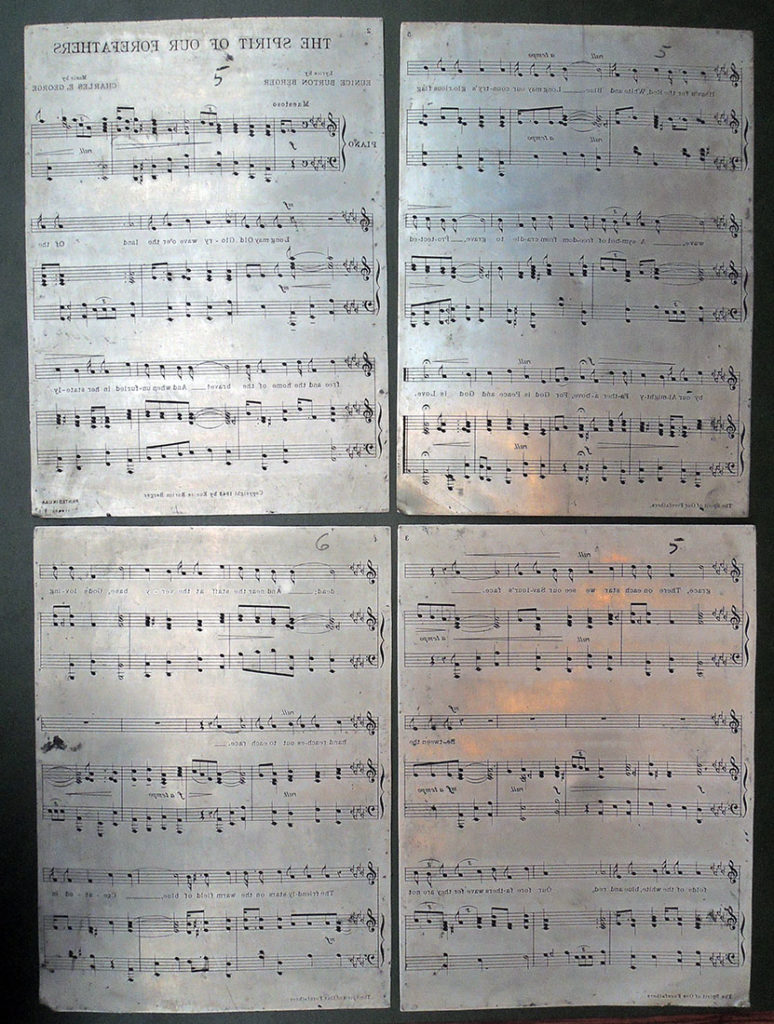

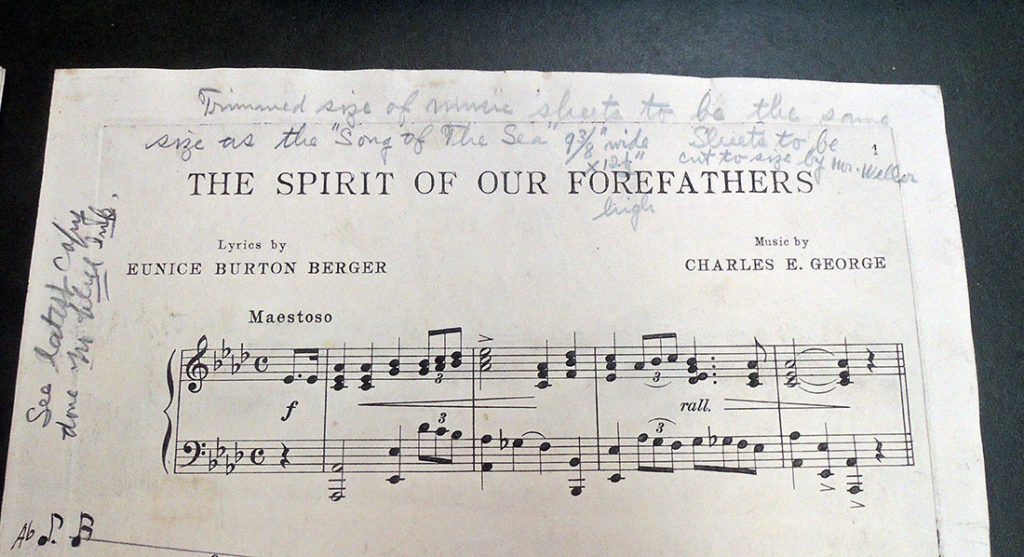

Engraved metal plates for “The Spirit of our Forefathers” come with instructions to the engraver as to what Berger wanted changed or improved. Although she shared credit with Charles E. George, bandmaster of the Irving Post of the American Legion in Roslindale, Massachusetts, on this and several other songs, it was Mr. and Mrs. Berger who produced sheet music and endlessly promoted the work.

Engraved metal plates for “The Spirit of our Forefathers” come with instructions to the engraver as to what Berger wanted changed or improved. Although she shared credit with Charles E. George, bandmaster of the Irving Post of the American Legion in Roslindale, Massachusetts, on this and several other songs, it was Mr. and Mrs. Berger who produced sheet music and endlessly promoted the work.

The Spirit of Our Forefathers music by Charles E. George and lyrics by Eunice Burton Berger

https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/mmb-vp-copyright/4511/

The 35 marching band parts for “On the Brink,” copyright applied for October 31, 1939, include Berger’s notation additions and printed title laid down at the head of the page. There is a contract dated August 31, 1944, between Eunice Burton Berger and Broadcast Music wherein she gives them exclusive rights to perform “The Song of the Sea” for five years, and they agree to pay her royalties. Along with this are four small brass plaques commemorating relatives lost at sea, possibly the inspiration for several of her song.

The remainder of the material includes a family genealogy by Berger, a number of photographs, and love letters between the dedicated couple. Canadian-born Eunice Burton Berger was married twice, first to Charles Redmond in Canada, and then to Louis H. Berger, a partner in his father C.L. Berger’s firm in Boston, manufacturers of Engineering and Surveying Instruments. The couple lived in the Dorchester section of Boston.

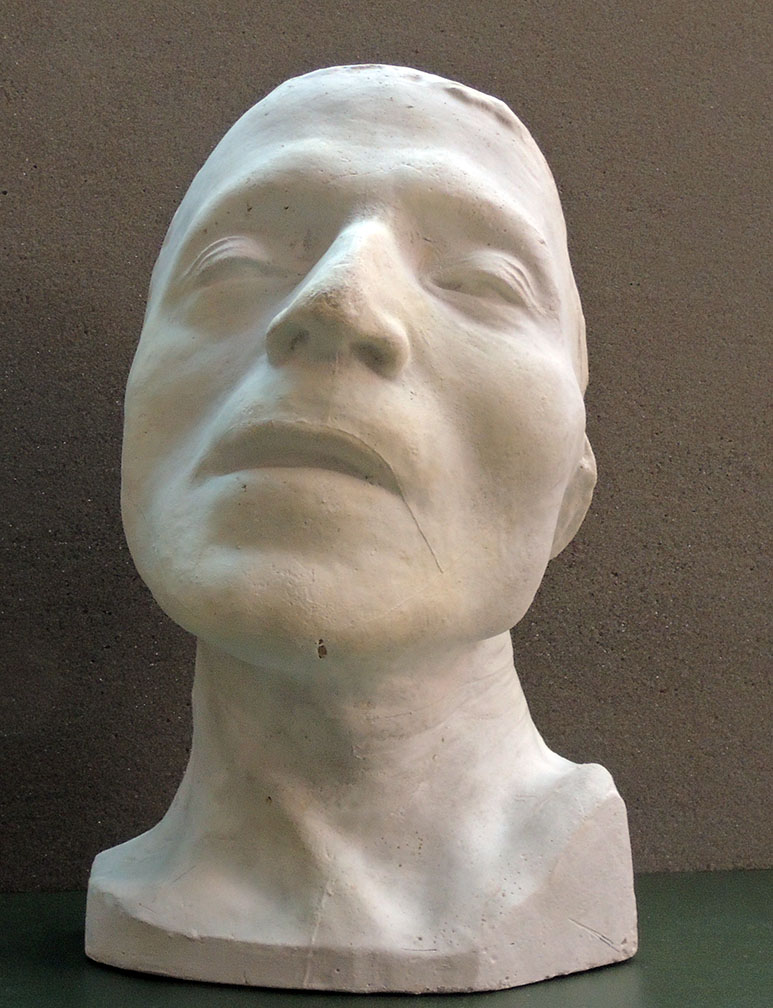

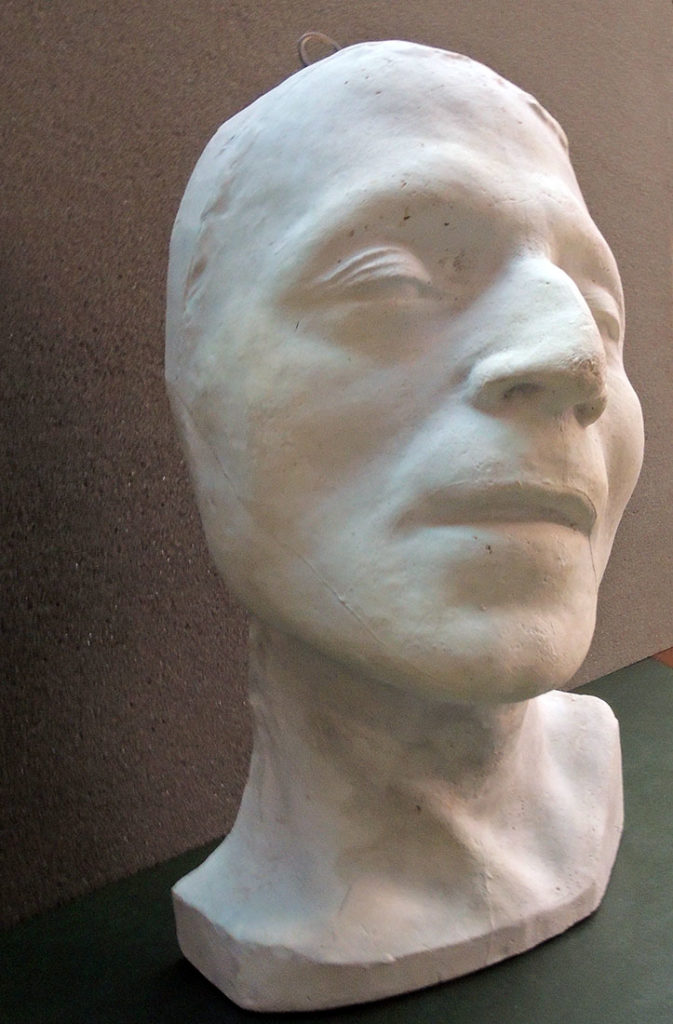

After many long years renovating and reconfiguring Firestone Library, Isamu Noguchi’s White Sun has returned to the Firestone front lobby. Created in 1966 and installed in 1970, Noguchi’s beautiful work is part of Princeton’s Putnam Collection of Sculpture, under the campus art collections managed by Lisa Arcomano. https://artmuseum.princeton.edu/campus-art

After many long years renovating and reconfiguring Firestone Library, Isamu Noguchi’s White Sun has returned to the Firestone front lobby. Created in 1966 and installed in 1970, Noguchi’s beautiful work is part of Princeton’s Putnam Collection of Sculpture, under the campus art collections managed by Lisa Arcomano. https://artmuseum.princeton.edu/campus-art