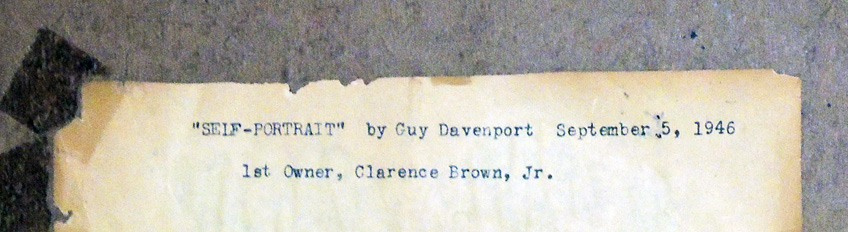

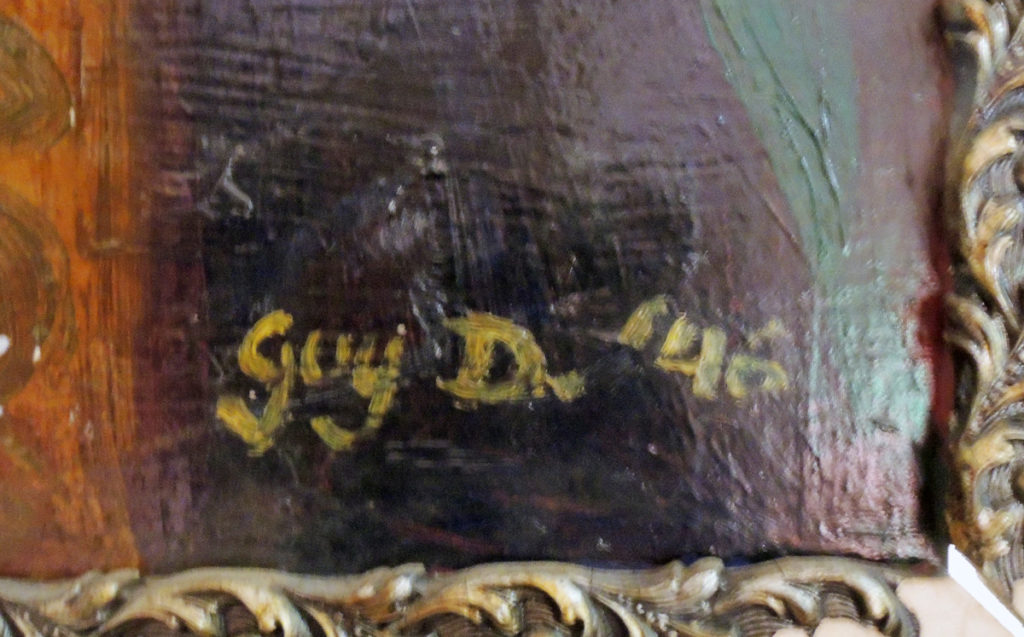

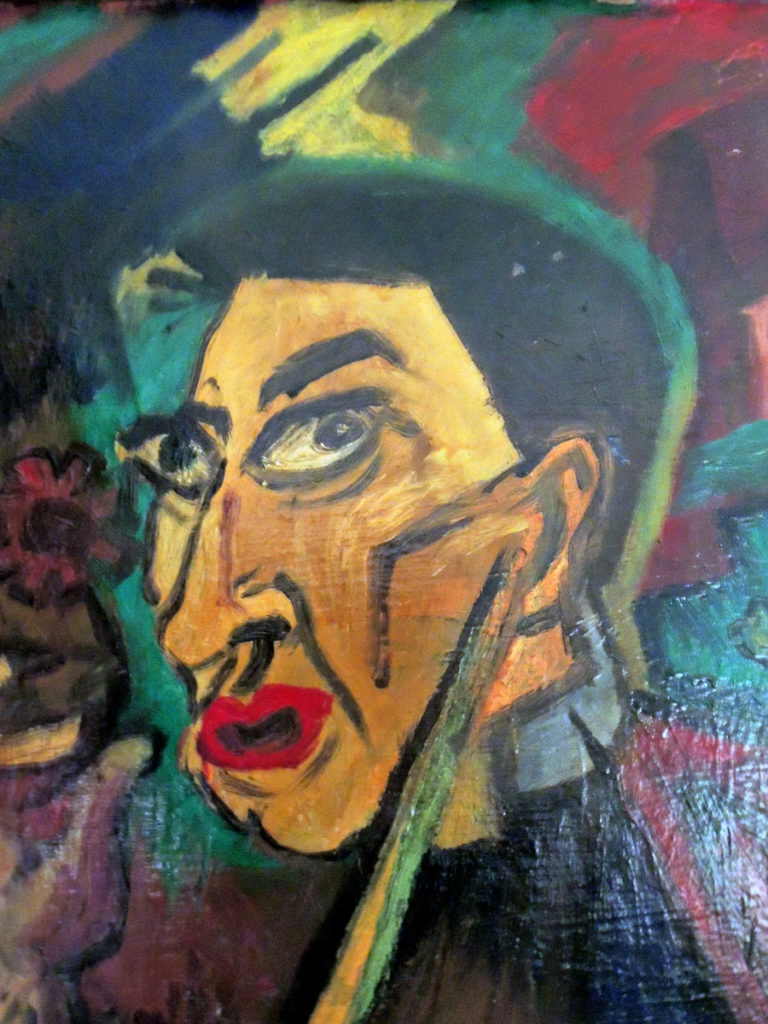

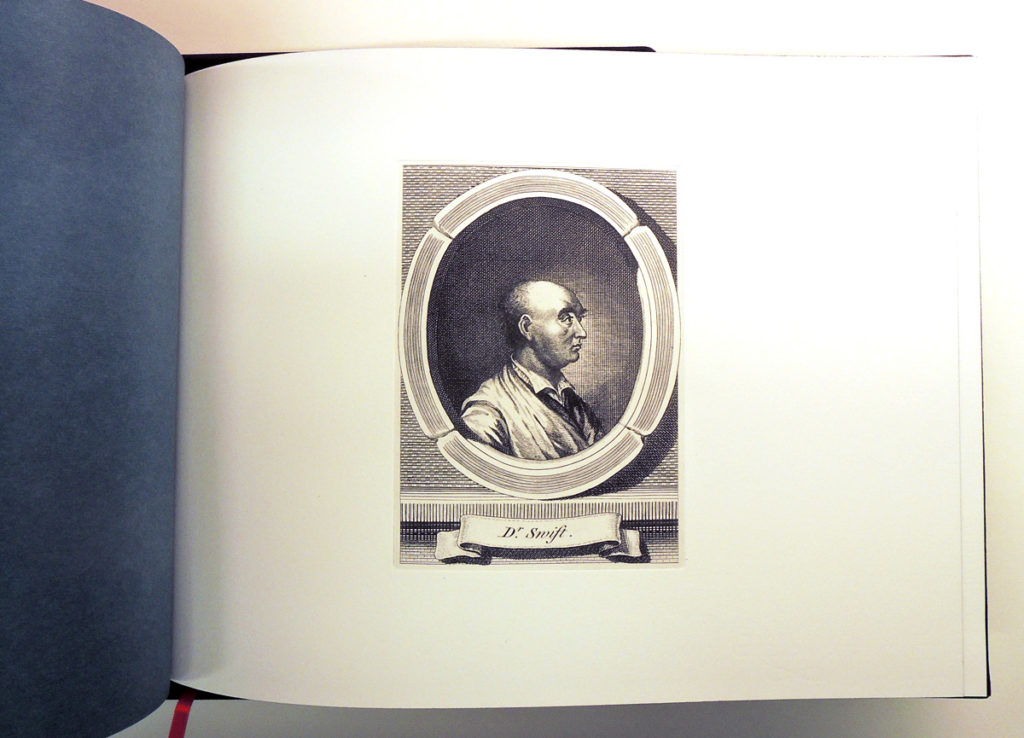

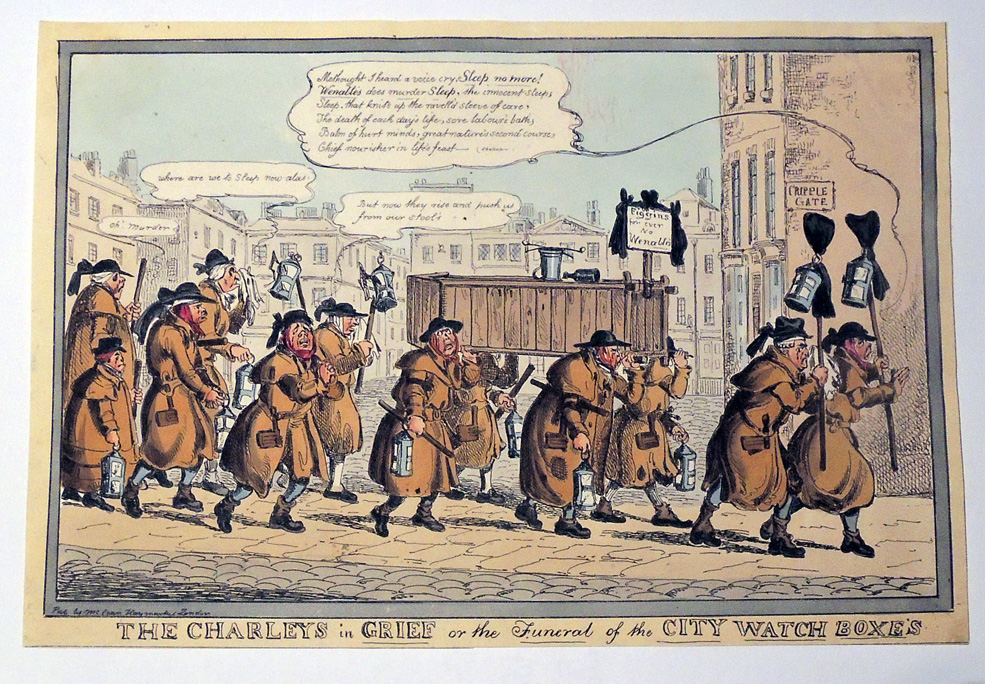

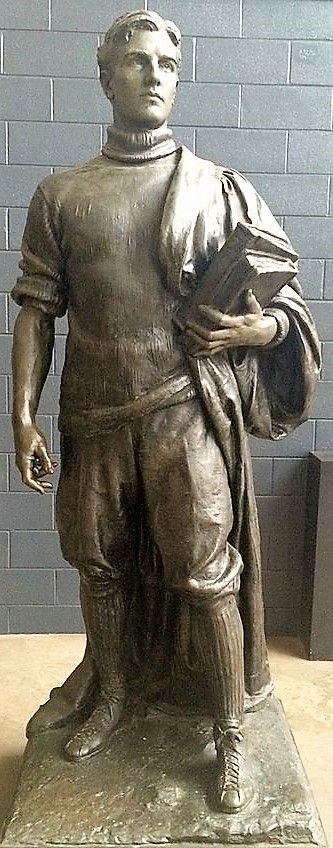

Guy Davenport (1927-2005), Self-Portrait, 1946. Oil on board. Graphic Arts Collection. Gift of Jacqueline Brown, given in honor of Clarence Brown. Reproduced with permission from the Davenport estate.

Thanks to the generous donation of Jacqueline Brown, we have acquired of a wonderful 1946 self-portrait by the American essayist, fiction writer, poet, translator, and painter Guy Davenport (1927-2005). The painting had been a gift by the artist to Clarence Brown (1929-2015), professor of comparative literature at Princeton University, who was a classmate of Davenport’s at the Anderson Boys’ High School in South Carolina and his life-long friend.

The recipient of a MacArthur Foundation “genius award,” also named a Distinguished Professor at the University of Kentucky, Davenport is remembered more for than his fifty published books than his visual art. Happily, Christopher Lehmann-Haupt titled his obituary for the New York Times, “Prolific Author and Illustrator.”

In his remembrance, Roy Behrens, University of Iowa, wrote, “Guy had drawn and painted since childhood (at age eleven, he had started an amateur newspaper in his hometown of Anderson, South Carolina, for which he wrote and also drew the pictures for all of the stories). As an adult, he used a crow quill pen to create the accompanying images for his own and the writings of others (I think the first of these I saw were in Hugh Kenner’s The Counterfeiters), in which he nearly always used a tedious method called “stippling” (still used today in scientific illustration), which is the “line art” equivalent of Georges Seurat’s pointillism.”

Davenport drew illustrations for Hugh Kenner’s The Stoic Comedians (1962) and The Counterfeiters (1968), as well as his own publications, Tatlin!: Six Stories (1974); Da Vinci’s Bicycle: Ten Stories (1979); Apples and Pears and Other Stories (1984); The Lark (1993); and Flowers and Leaves (1961). A prolific author, if we have missed some, please let us know.

For more, see Erik Anderson Reece, A Balance of Quinces (1996), Rare Books: Leonard Milberg Coll. of American Poetry (ExRML) PS3554.A86 B34 1996; the only book so far about Guy as a visual artist.

Also The Guy Davenport reader; edited and with an afterword by Erik Reece (Berkeley, CA: Counterpoint, [2013]). Firestone Library (F) PS3554.A86 A6 2013

For more author’s portraits in the Graphic Arts Collection, see https://blogs.princeton.edu/graphicarts/2009/12/the_authors_portrait.html