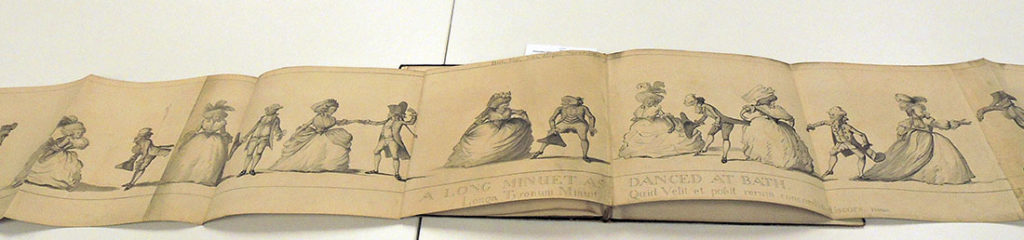

We were asked recently about the watercolor attributed to Alfred Edward Chalon (1780-1860) of the four leading ballerinas of the 1840s, Fanny Cerrito, Lucile Grahn, Carlotta Grisi, and Marie Taglioni, in the Pas de Quatre, composed by Jules Perrot and danced on July 12, 1845. This painting was the source for a popular lithograph by Thomas Herbert Maguire (1821-1895), widely circulated.

We were asked recently about the watercolor attributed to Alfred Edward Chalon (1780-1860) of the four leading ballerinas of the 1840s, Fanny Cerrito, Lucile Grahn, Carlotta Grisi, and Marie Taglioni, in the Pas de Quatre, composed by Jules Perrot and danced on July 12, 1845. This painting was the source for a popular lithograph by Thomas Herbert Maguire (1821-1895), widely circulated.

According to commentary by the Victoria and Albert Museum,

“There were no men in the ballet–the ballerina was now the public’s favourite and the male dancer’s role was reduced to lifting and supporting her. In the coming years, his position declined even further, until he was all but banished from the stage and male roles were performed by girls in men’s clothing. By this time a recognisable ‘ballet’ costume had evolved, which still forms the basis of many ballet costumes today. It was originally based on fashionable dress of the period, but gradually crystallised into a low-cut pointed bodice and a bell-shaped, knee-length skirt formed of tiers of tarlatan with a diaphanous top layer.”

Our watercolor was a gift of Allison Delarue, of whom Mary Ann Jensen, former Curator of the William Seymour Theatre Collection, wrote,

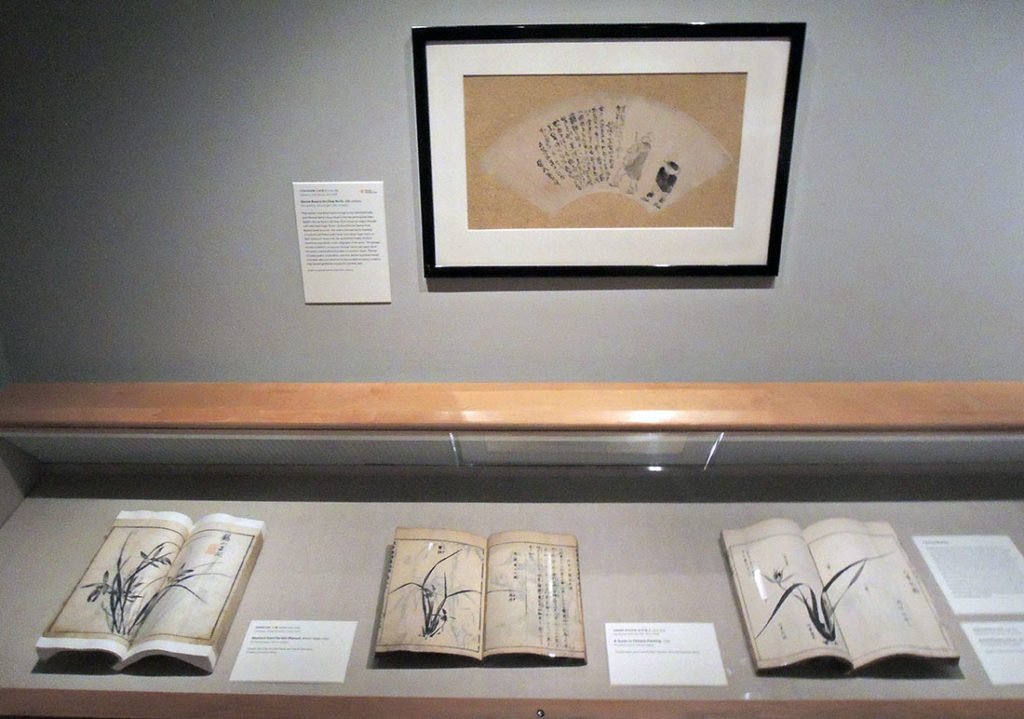

“Allison Delarue, Class of 1928, is a graduate of the Peddie School who received both his Bachelor of Arts and Master of Arts degrees from Princeton University. While continuing graduate studies at Oxford University he became fascinated with the renaissance of ballet in England; he studied dance with the Hon. Martin-Haney and bought his first ballet print at Cyril Beaumont’s famous London bookshop in Charing Cross Road.

Returning to the United States, he pursued his interest in the ballet while on the staff of the Cooper Union Museum in New York City. A talented photographer as well as a collector and writer, for many years Mr. Delarue was on the staff of the McCarter Theatre in Princeton. His professional memberships have included the Theatre Library Association and the American Society for Theatre Research.”

http://libweb5.princeton.edu/visual_materials/delarue/Htmls/index.html