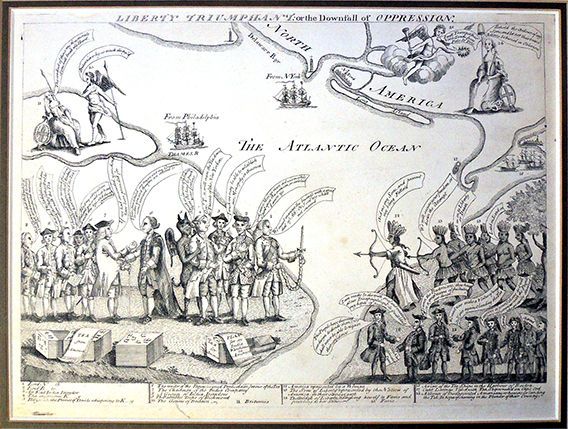

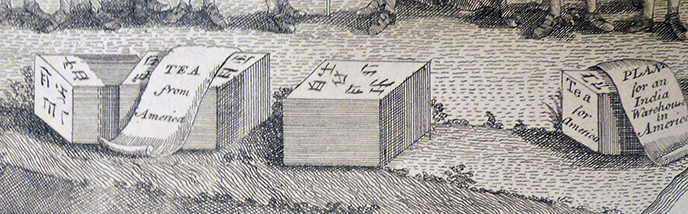

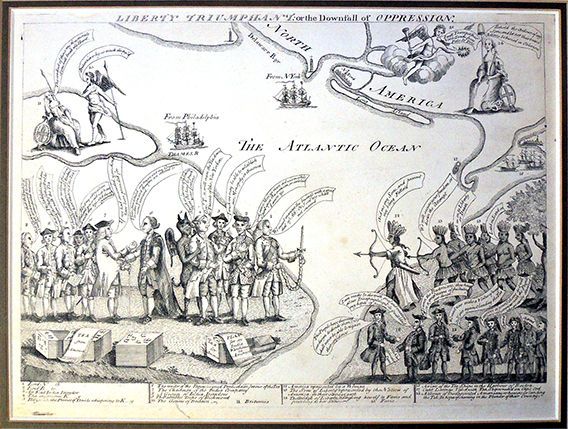

Attributed to Henry Dawkins (born England, active in New York, 1754-57; Philadelphia, 1757-72?; New York 1772-80), Liberty Triumphant or The Downfall of Oppression, published after December 27, 1773, but before April 1774. Engraving. 275 x 377mm. Purchased with funds given by the Friends of the Princeton University Library. Graphic Arts Collection GAX 2021- in process

Thanks to the generous support from the Friends of the Princeton University Library, the Graphic Arts Collection recently acquired a remarkable pre-revolutionary war print, entitled Liberty Triumphant or The Downfall of Oppression, significant not only for the history and symbolism but for its excellent provenance. While many American historians focus on 1775 and after in terms of print and propaganda, it was 1773 and 1774 when opinions were more fluid on both sides of the Atlantic that are at once less well-known and deeply interesting.

Our impression of the rare Liberty Triumphant engraving comes from the highly regarded collection of Ambassador J. William Middendorf II (born 1924), which “includes some of the most important documents and works on paper representing the history of the United States from its 17th-century colonial origins through the American Revolution and the Founding Era.” As noted in Barron’s profile “the 96-year-old Middendorf II served as the U.S. ambassador to the European Union from 1985-87, and ambassador to the Netherlands from 1969 to 1973. He also served as the Secretary of the Navy from 1974-77.” He was also a preeminent collector of early Americana with an excellent eye, compelling no less than the Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York, N.Y.) and the Baltimore Museum of Art to mount a major exhibition in 1967 of his American paintings and historical prints. In 1973, Sotheby’s held a sale of American historical prints, books, broadsides, maps from the collection of Ambassador and Mrs. J. William Middendorf II, but at that time the family retained their favorite pieces, unwilling to give them up, until now.

Our impression of the rare Liberty Triumphant engraving comes from the highly regarded collection of Ambassador J. William Middendorf II (born 1924), which “includes some of the most important documents and works on paper representing the history of the United States from its 17th-century colonial origins through the American Revolution and the Founding Era.” As noted in Barron’s profile “the 96-year-old Middendorf II served as the U.S. ambassador to the European Union from 1985-87, and ambassador to the Netherlands from 1969 to 1973. He also served as the Secretary of the Navy from 1974-77.” He was also a preeminent collector of early Americana with an excellent eye, compelling no less than the Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York, N.Y.) and the Baltimore Museum of Art to mount a major exhibition in 1967 of his American paintings and historical prints. In 1973, Sotheby’s held a sale of American historical prints, books, broadsides, maps from the collection of Ambassador and Mrs. J. William Middendorf II, but at that time the family retained their favorite pieces, unwilling to give them up, until now.

Henry Dawkins has an important connection with Princeton University. While we know very little about the artist, who immigrated to the American colonies around 1753 and settled in Philadelphia, we know he traveled regularly to New York City on the coach that rested in Princeton, NJ. He worked as assistant to James Turner until 1758, when he opened his own engraving shop. Of special note to Princeton friends is Dawkins’ engraving after William Tennant, A North-West Prospect of Nassau-Hall, with a Front View of the Presidents House, in New-Jersey, published in Samuel Blair’s An account of the College of New-Jersey, 1764. Two original copies, bound and unbound, are held by the Princeton University Library. We also have the rare portrait of his contemporary, the abolitionist Benjamin Lay, printed by Dawkins while both were living in the area. Significant research still needs to be done on this important but little known artist and what better place to focus that research than Princeton University.

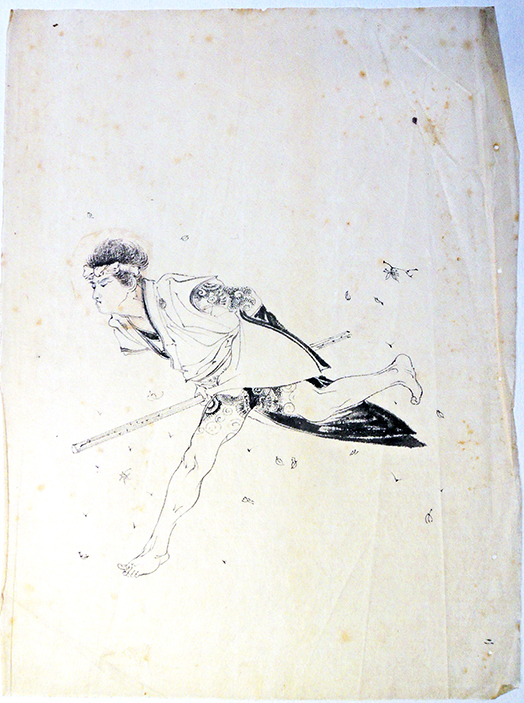

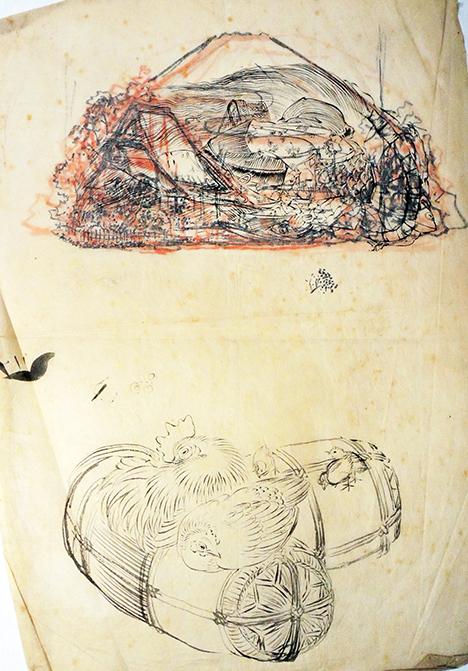

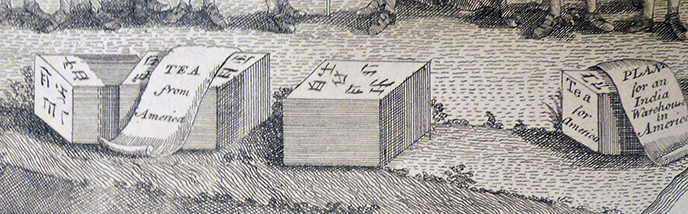

Finally and most important is the inventive iconography and compelling narrative of this rare political print. The artist’s opposing scenes concern the American resistance, beginning late 1773 and early 1774, to the tea tax and the East India Company monopoly, presumably engraved shortly after the Boston Tea Party but before news arrived of the retaliatory “Intolerable Acts” that would close the Port of Boston. There is no evidence that Dawkins produce it as a magazine illustration or book frontispiece but rather printed it on his own, as one of the few large, separate engravings of the American Revolutionary period.

Each of the historical figures is identified from a key provided at the bottom, including Lord North, Lord Bute, John Kearsley, John Vardill, the Duke of Richmond, and others (18 in all). Interspersed with the living characters are allegorical figures, such as Beelzebub, the Prince of Devils, who whispers to Kearsley, “Speak in favor of ye [the] Scheme Now’s the time to push your fortune” and Kearsley replies “Gov T[ryon] will cram the Tea down the Throat of the New Yorkers.”

Our new Indigenous Studies department at Princeton University will find the depiction of America split equally between transplanted Europeans and Native Americans worth study. Labeled the “Sons of Liberty,” one says “Lead us to Liberty or Death,” printed approximately one year before Patrick Henry made his speech to the Second Virginia Convention proclaiming “Give me liberty or give me death.” The Native Americans are in fact colonists dressed up to look like American Indians, led by a queen rather than a male warrior, reflected above in the Goddess of Liberty, who proclaims “Behold the Ardour of my Sons and let not their brave Actions be buried in Oblivion.”

In his study of the four most important American political prints, including Liberty Triumphant, E.P. Richardson writes:

“Eighteenth-century American political prints are a difficult but fascinating study. They are extremely rare. The men and events depicted are often buried deep beneath onrushing time or, if remembered, are presented in so unfamiliar a perspective as to be hardly recognizable. But this is precisely the print’s importance. They show us how history felt as it happened; not the long chain of events of which we, looking backwards, see only the outcome.”

John William Middendorf II understood the importance of these rare sheets. He had the time and resources to collect some of the rarest and most important works representing the history of the United States from its 17th-century colonial origins through the American Revolution and the Founding Era. Now Princeton students can enjoy some of the same treasures.

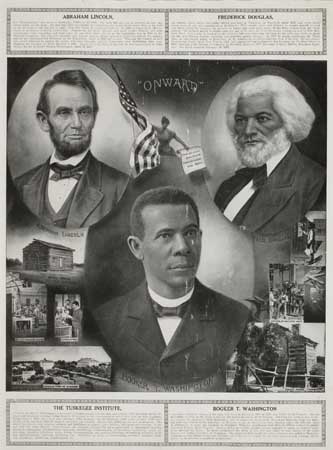

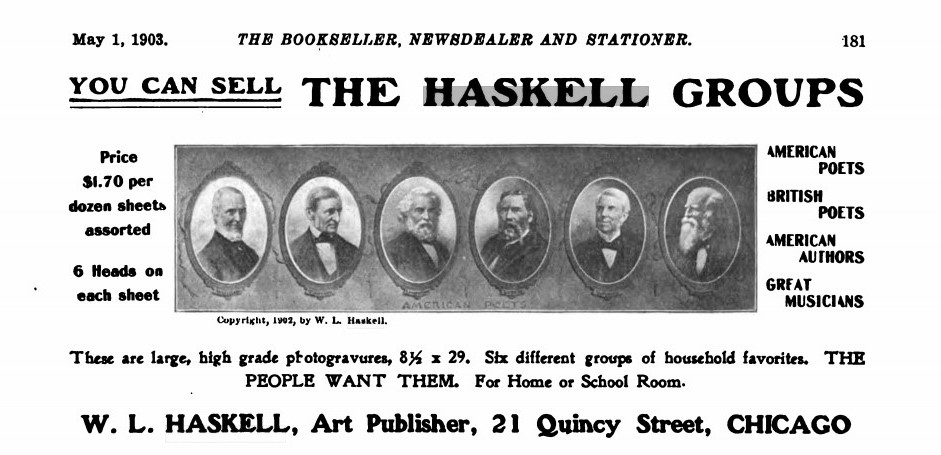

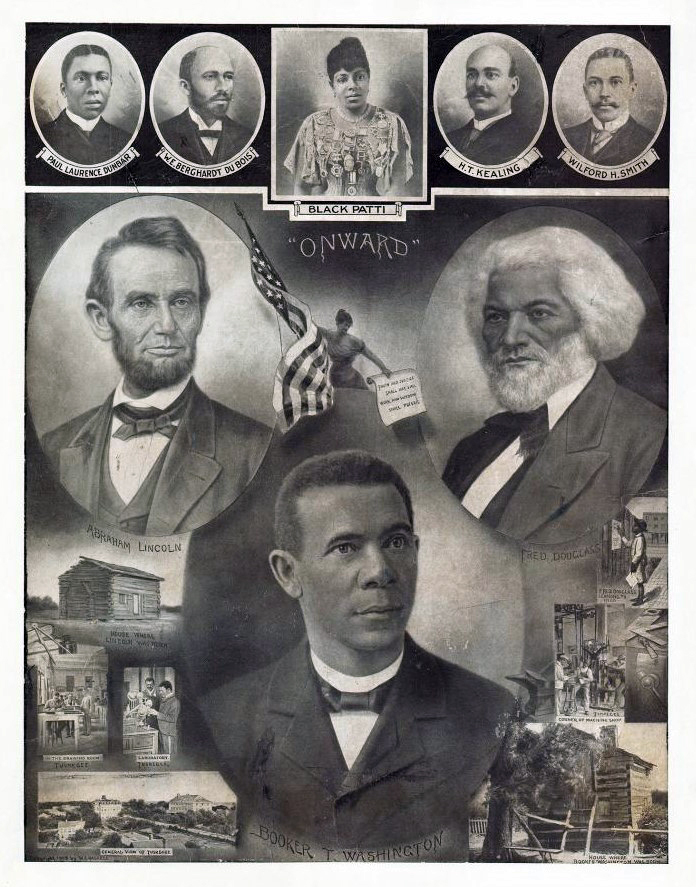

Onward ([Chicago:] W.L. Haskell, 1903). Poster mounted on linen and framed. Graphic Arts Collection GAX 2021- in process

Onward ([Chicago:] W.L. Haskell, 1903). Poster mounted on linen and framed. Graphic Arts Collection GAX 2021- in process