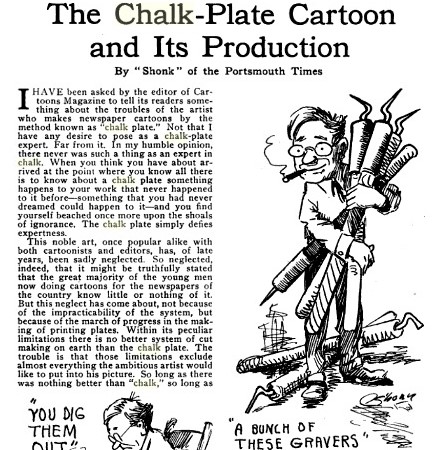

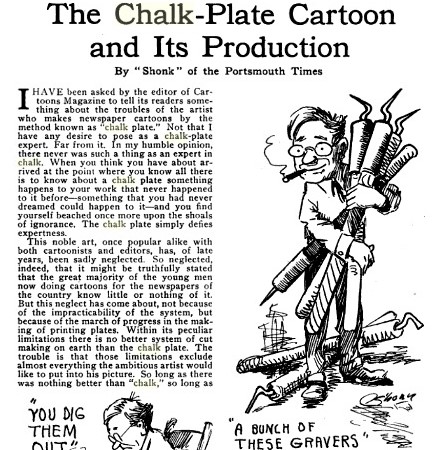

Cartoons Magazine 4, Issue 4 (1913): 401-03

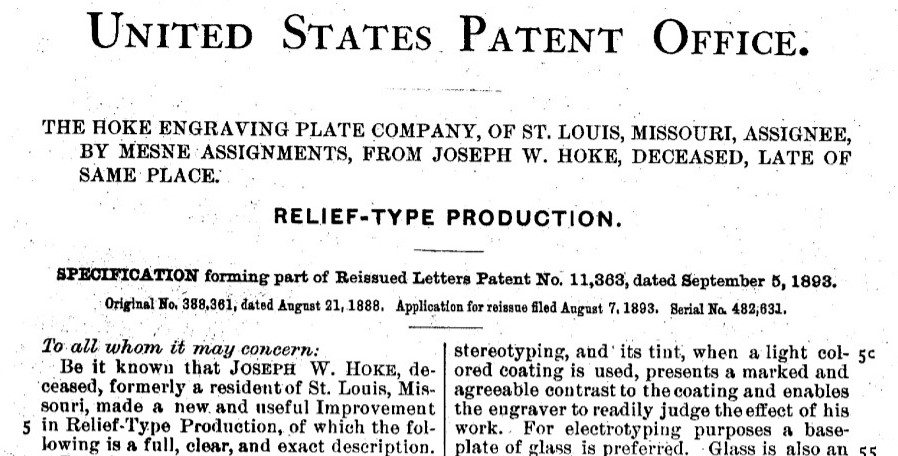

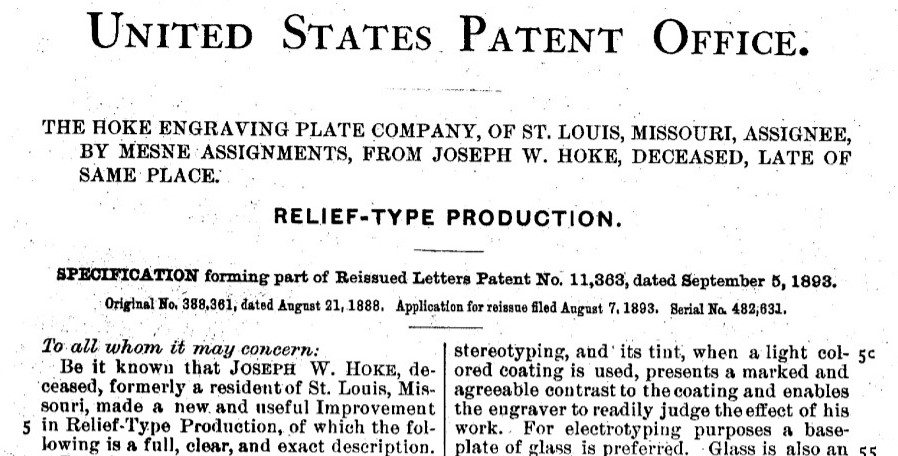

Beginning in 1885 (copyrighted 1888), wood engraving faced serious competition from a new reproductive process. No, not the Kodak camera. It was the chalk-plate process, or Hoke process, named after Joseph W. Hoke who developed a method of free-hand drawing on a chalk covered metal plate, which was then stereotyped and ready for printing in one or two hours, greatly decreasing the time needed to produce illustrations for breaking news stories and other daily newspaper work.

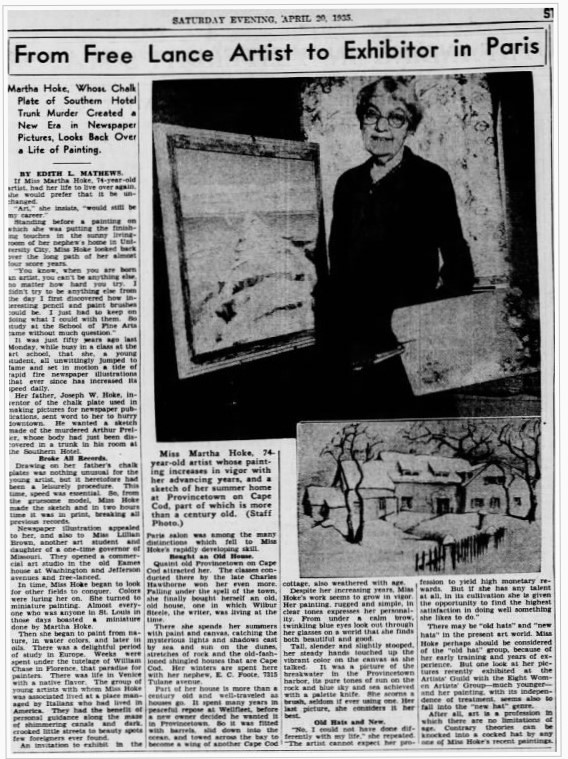

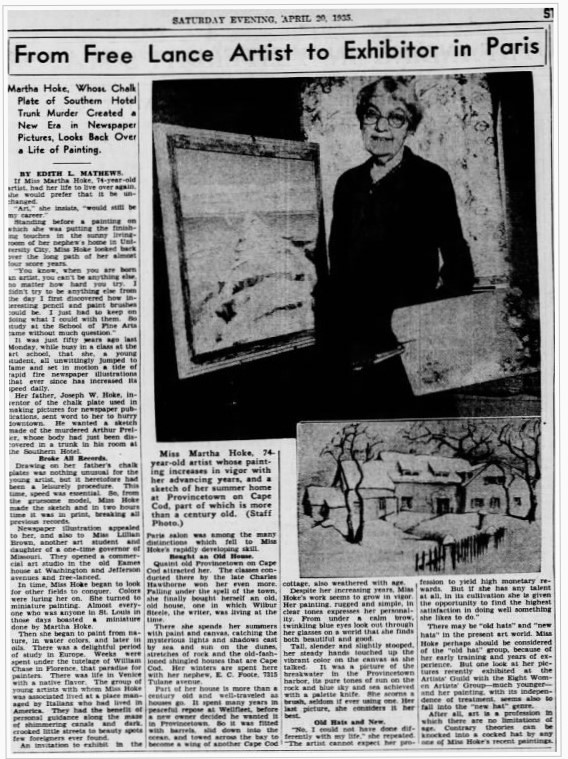

According to Anne Johnson’s 1914 Notable women of St. Louis, it was Hoke’s daughter and professional artist Martha Hoke (1861-1939) who produced the first and still most famous chalk-plate illustration of a murder victim discovered in a trunk, which she was able to sketch around 1:00 p.m. and the picture printed in the regular afternoon edition of the Post-Dispatch a few hours later.

Miss Martha Hoke… was the first person in St. Louis to make drawings for newspaper illustrations. Her father, Joseph W. Hoke, made a discovery in the line of engraving which he perfected by much experiment upon plates capable of producing, in a very short time, a type which could be set up with reading matter. This was the first successful engraving process using the artist’s drawing directly. Miss Hoke gave her father much assistance in the trial drawings necessary to perfect this method. All illustrations had, up to that time, been engraved on wood, or steel, or stone, or etched on copper. Mr. Hoke prepared a chalk composition, baked upon a steel plate, of such consistency that a drawing could readily be made by a pointed stylus bent at such an angle that when held as a pen or pencil the point would be vertical.

The drawing so made is placed in a stereotyping box and as a matrix it is cast in type metal. This type could be produced in a very short time. The possibilities for newspaper illustrations—which previous to that had been very meager and poor—were developed by an emergency, which at once placed this invention in great demand and general use. The event which so suddenly brought success financially was a murder at the Southern Hotel by a man named Maxwell, who hid the body of his victim, Preller, in a trunk which he left in a room he had occupied. The discovery of this brought out an extra edition of one of the daily papers, with a drawing by Miss Hoke. This famous case made chalk plates known to all newspapers everywhere.

Outside the big city papers, such as the New York Times or the Washington Post, many publishers could not afford to maintain a full photoengraving department and so, used chalk-plates for all their illustrations well into the twentieth century. Manuel Rosenberg included a chapter in his 1922 The Manuel Rosenberg Course in Newspaper Art entitled The Chalk Plate Method for the Artist in the Small Town. “Before the invention of the photoengraving process,” he writes, “the newspaper artist and the cartoonist usually used chalk plates. Today the chalk plate is practically a medium of the past. For small-town publications, however, it is often a more serviceable medium than the up-to-date photo-engraving process.”

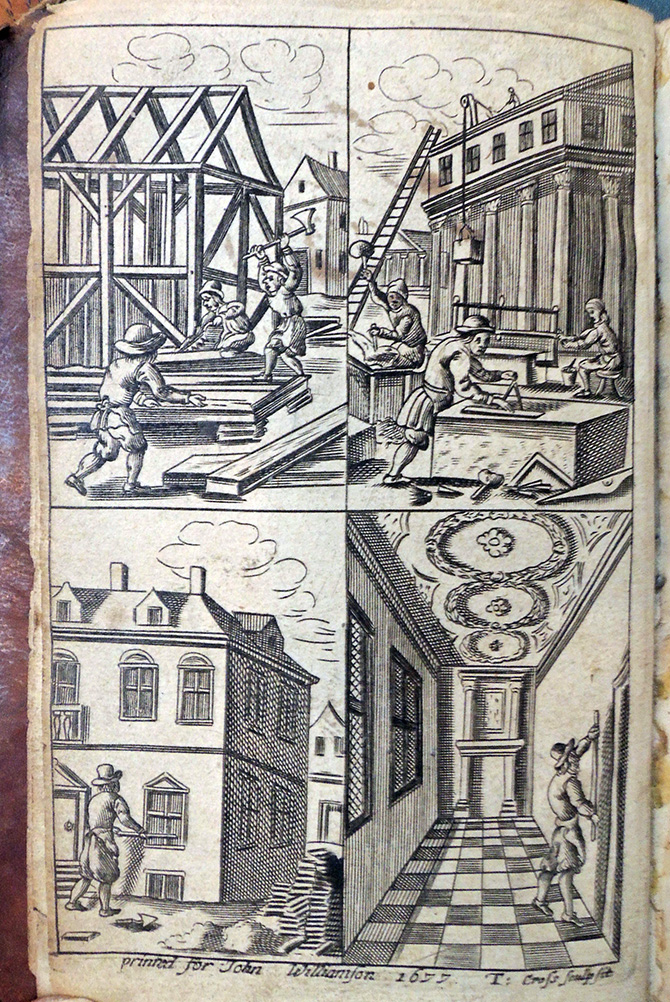

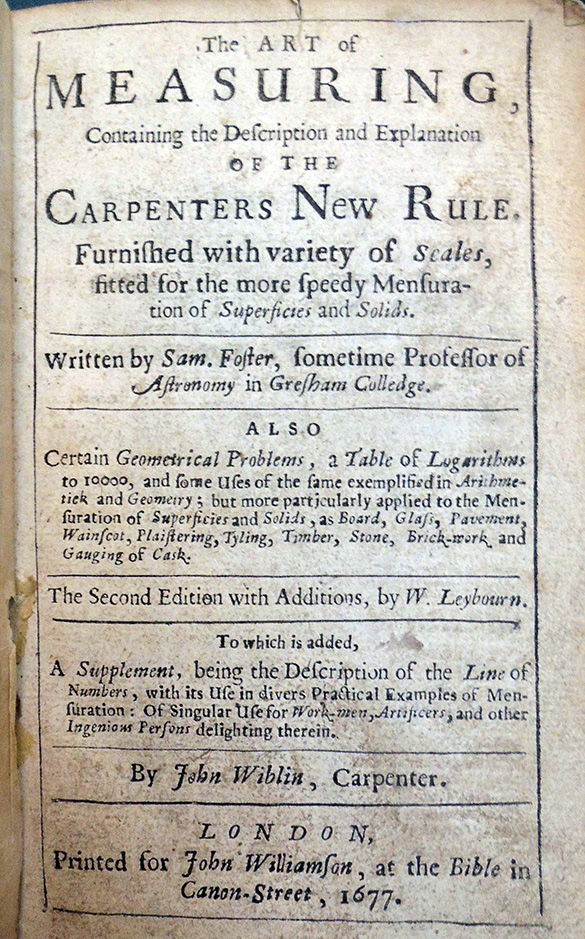

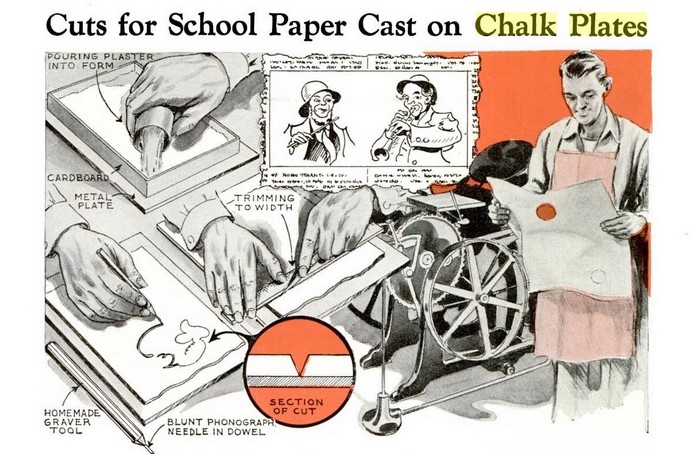

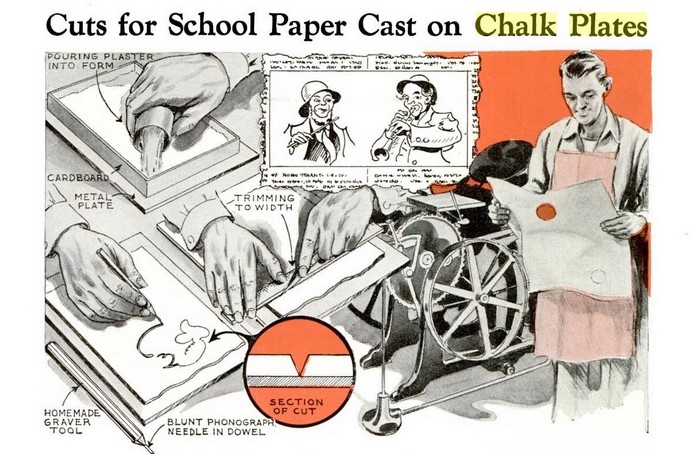

As late as 1941, Popular Mechanics was suggesting chalk plates for cartoonist of high school newspapers [below] and offering a full-page description of the process complete with illustrations. (volume 75, no. 1, January 1941, p.117)

Many lengthy descriptions of the process have been published. One appeared in The Art Amateur: Devoted to Art in the Household 44, no. 6 (May 1901): 158, entitled “How to make chalk plates.”

The following is the method of producing on “chalk plates” such illustrations as are used for general newspaper work: A metal plate, covered with a coating of chalk about a sixteenth of an inch thick, is put into the hands of the draftsman. It should be the actual size of the illustration to be made. The draftsman draws upon the plate with a metal point or needle, like a shoemaker’s awl; every time he makes a line he removes the chalk from that part of the plate, and the exposing of the metal makes his drawing appear dark, contrasted with the whiteness, of the chalk. [In much the same way the etcher removes his etching ground from a copper plate with the etching needle; the etching ground, however, is wax, and it usually is darkened by smoking, so that, the copper of the plate being light, the drawing appears light upon a dark ground.]

When the artist has finished his drawing—which is really a scratching away of the chalk—the plate is handed to a stereotyper, who makes a stereotype of it. This is done in the following way: It is put into a casting box, not unlike an iron waffle pan, which when closed leaves an opening about one-fourth of an inch in front of the plate, and on the top of which there is an opening, into which the stereotyper pours liquid type metal, as a boy pours melted lead into a bullet mould. The metal fills the vacuum in front of the plate and runs into each gully or furrow which the draftsman’s needle point has made. Of course where the chalk has not been removed, the type metal does not go; when the metal is cold and the casting—box opened, we find a thin plate of metal where the lines rise to an even height, wherever the artist has scratched a line down to the metal plate; but the plate is lower wherever the unremoved chalk prevented the liquid touching the metal plate. This crust of type metal fastened to a block, so that it is type high, resembles a wood engraving or a photo-engraved plate, and serves the same purpose. When the inked rollers of the printing press go over it, they ink the raised lines only, which correspond to the lines the artist drew, and hence it prints just like type.

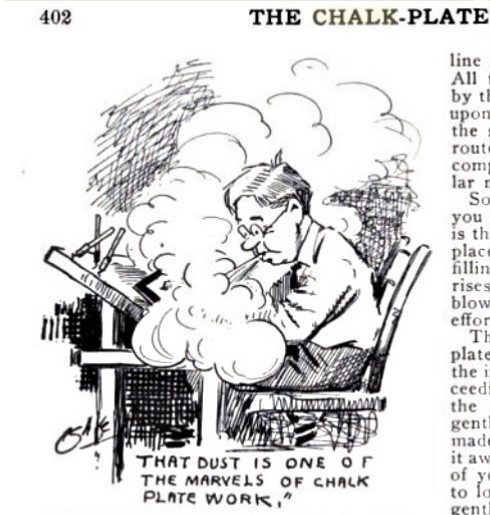

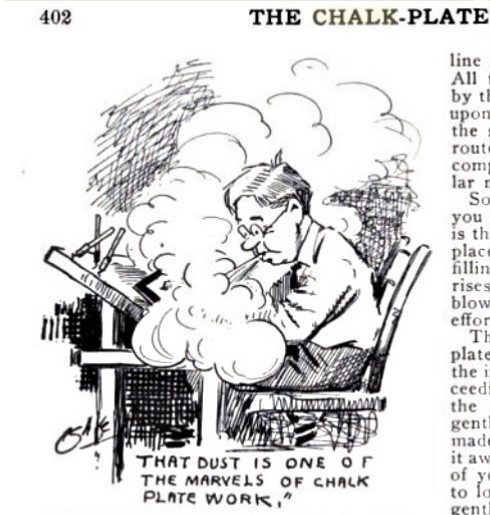

This method of making illustrations for the newspapers has great advantages and disadvantages. It has the advantage of cheapness, for the plates cost next to nothing, and when the castingbox is once bought the expense of type metal and the recoating of the plates is very slight. It is a very quick method also, as an artist can draw a portrait half an hour before the paper goes to press. His drawing may take fifteen minutes and the casting fifteen minutes more. In photo-engraving, the photographing and etching of the plate takes a couple of hours. The disadvantage of the method is that the artist must make his drawing the exact size it is to be printed, while for photo-engraving he usually works on a larger scale, which is not only easier for him, but when a drawing thus made is reduced it has a greater appearance of fineness and finish than a drawing made small. Then, too, the laying bare of the plate with a metal point, and raising a dust of chalk, which sometimes covers up the lines, is not as pleasant a way of working—does not seem as natural as drawing with a pen on Bristol board. In pen drawing. also, more pressure on the pen turns a thin line into a thick one; in the chalk-plate process, to thicken a line you either have to go over it several times, removing chalk on its sides, or else use a larger instrument than you used for the fine lines.”

See also: R.M.A., “Stereotyping Chalk Plates,” The Inland Printer 28, no. 2 (November 1901): 194-96.

Note, chalk-plates should not be confused with chalk manner engraving from the eighteenth century. https://www.oxfordartonline.com/groveart/view/10.1093/gao/9781884446054.001.0001/oao-9781884446054-e-7000020168

Neither should it be confused with relief line block printing, a technique that uses a negative of a line drawing being contact printed onto a photosensitized metal plate. Light hardens this emulsion into an acid resist while non-exposed areas are washed away in warm water. When etched in a bath of acid the metal surrounding the emulsion protected lines is eaten away forming a low relief, which can be printed as any relief matrix.