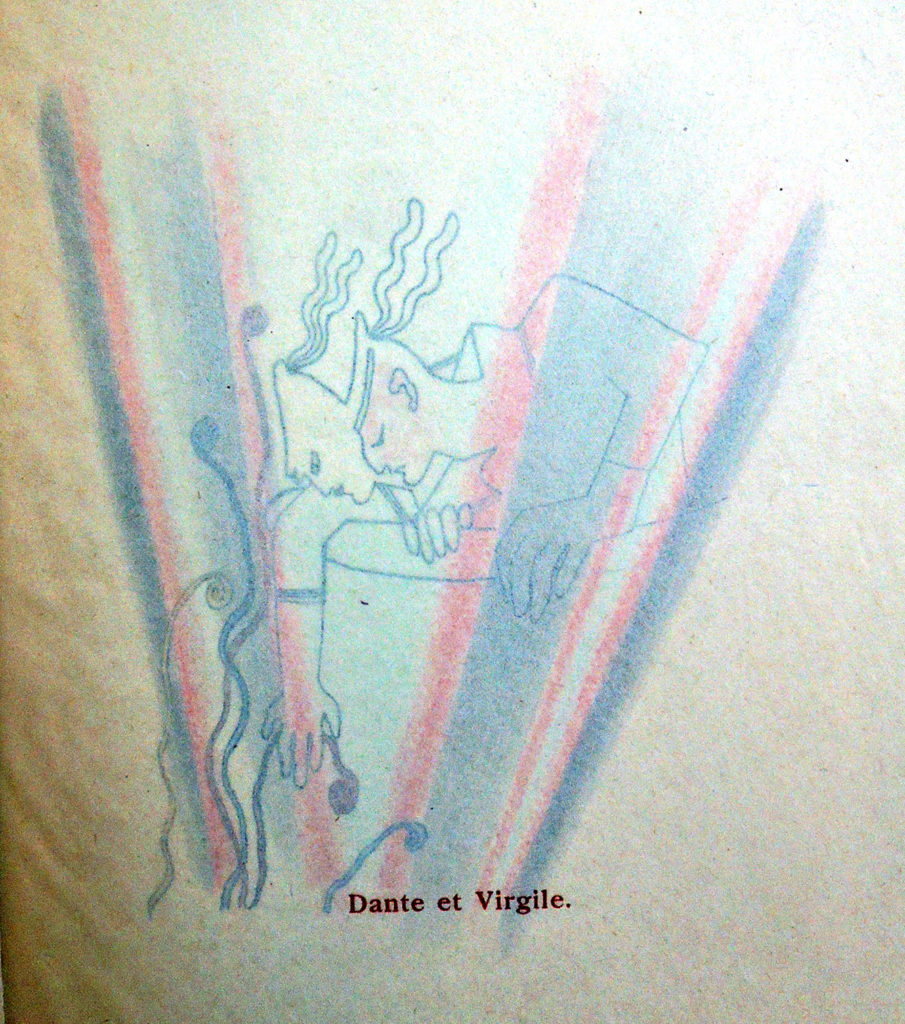

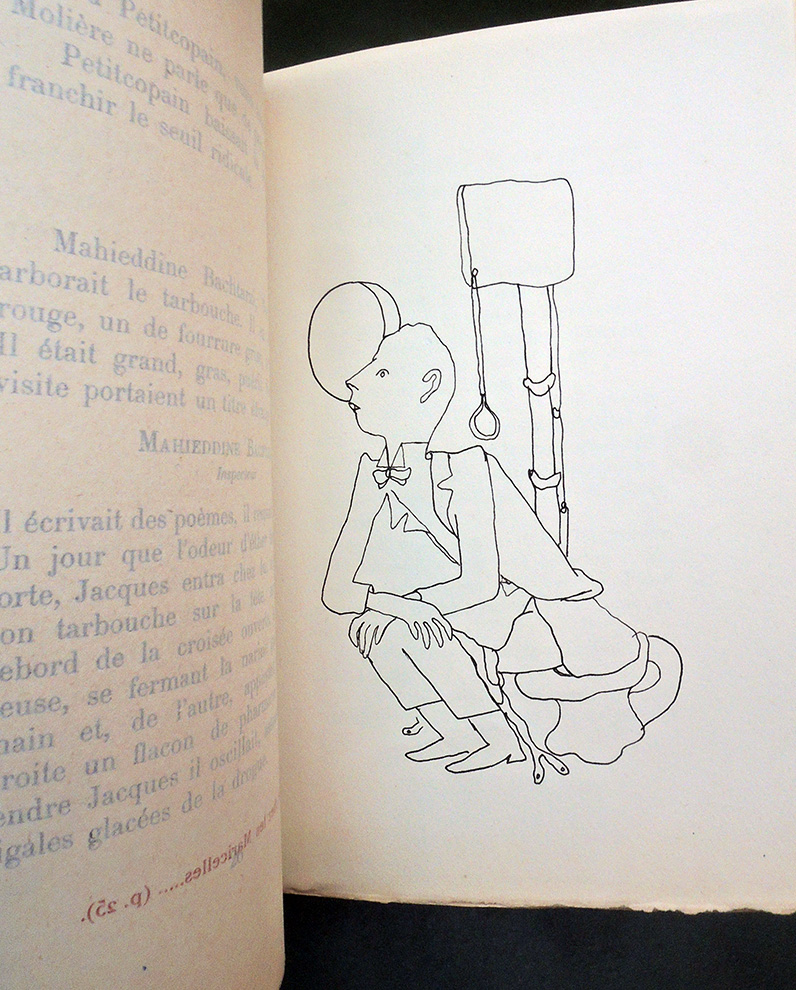

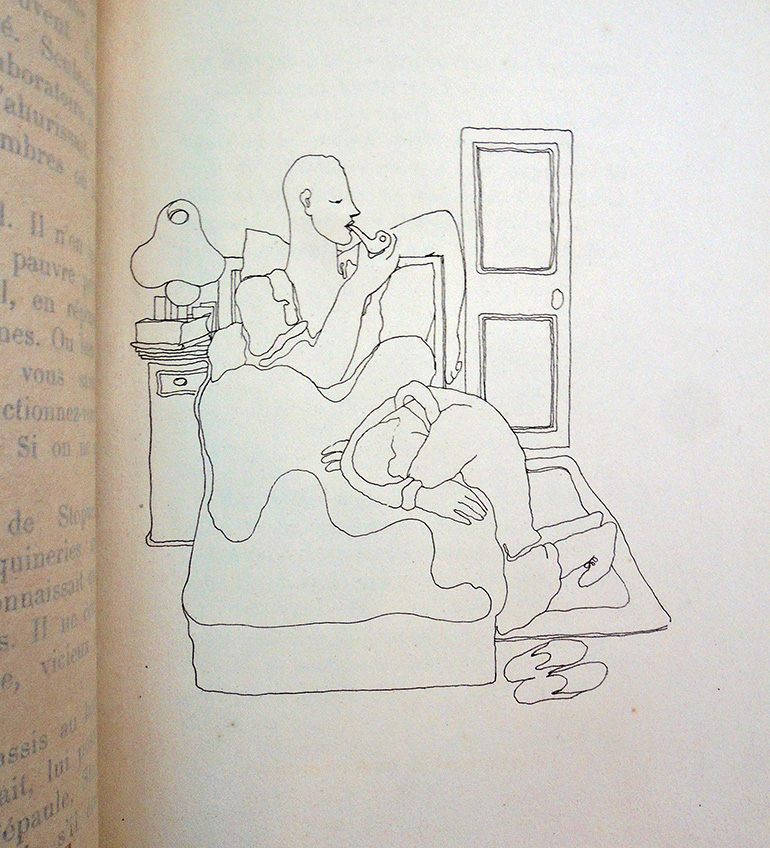

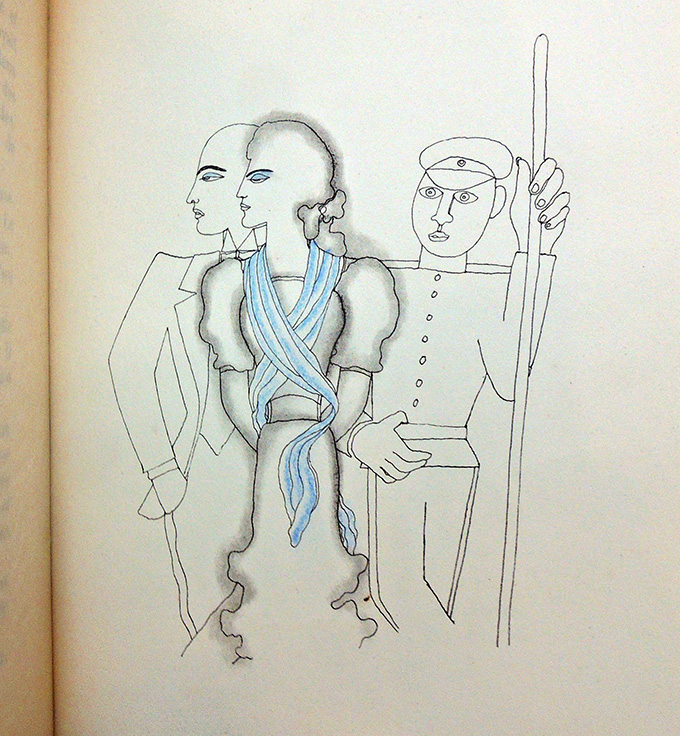

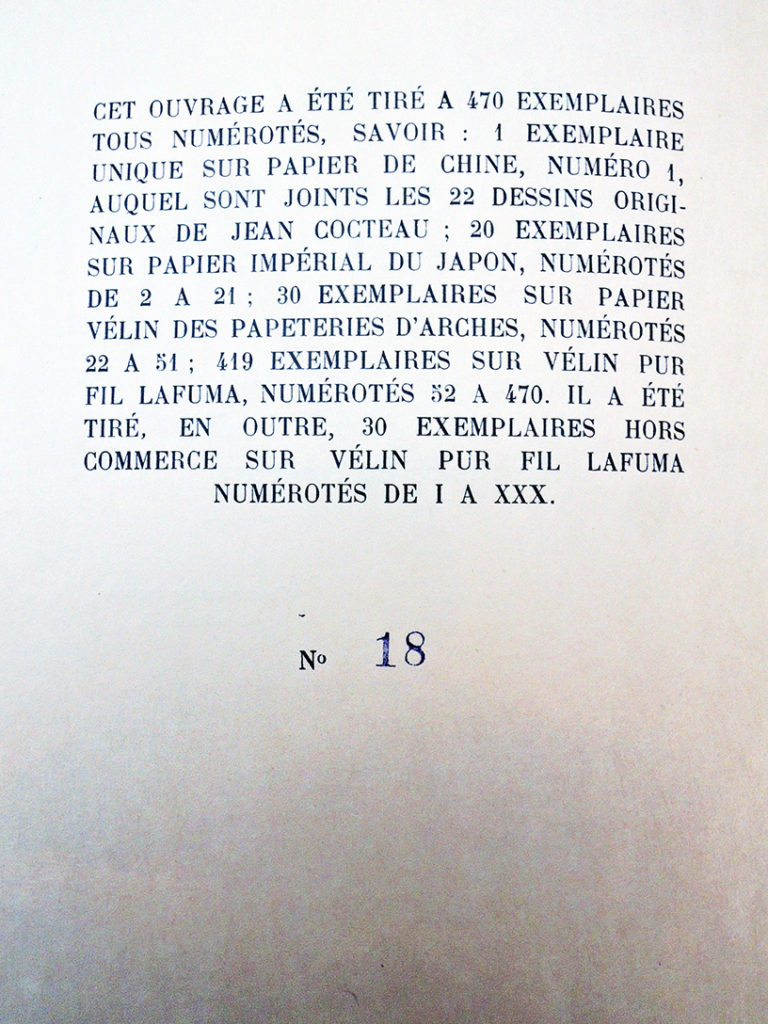

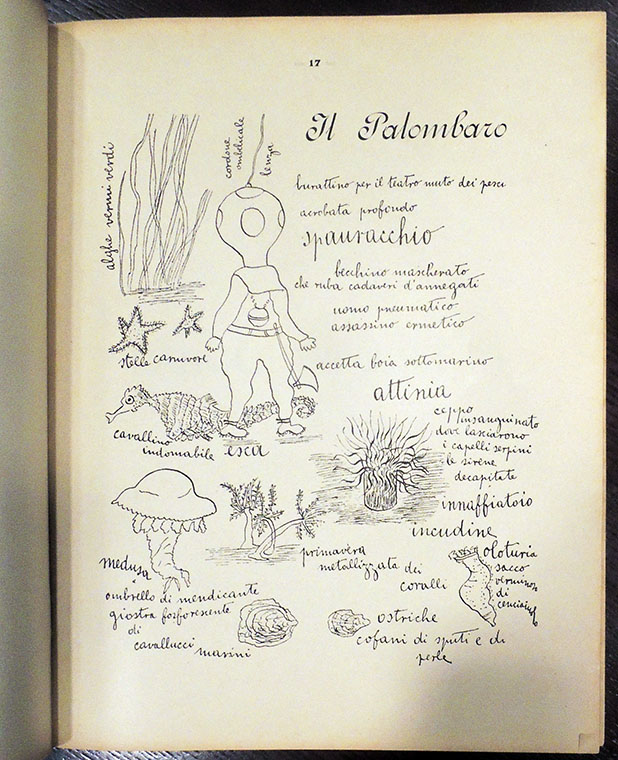

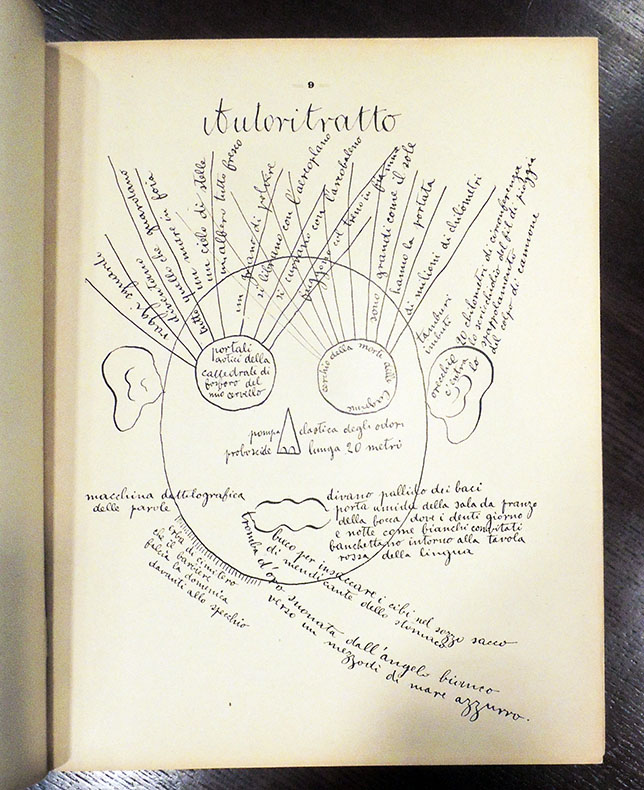

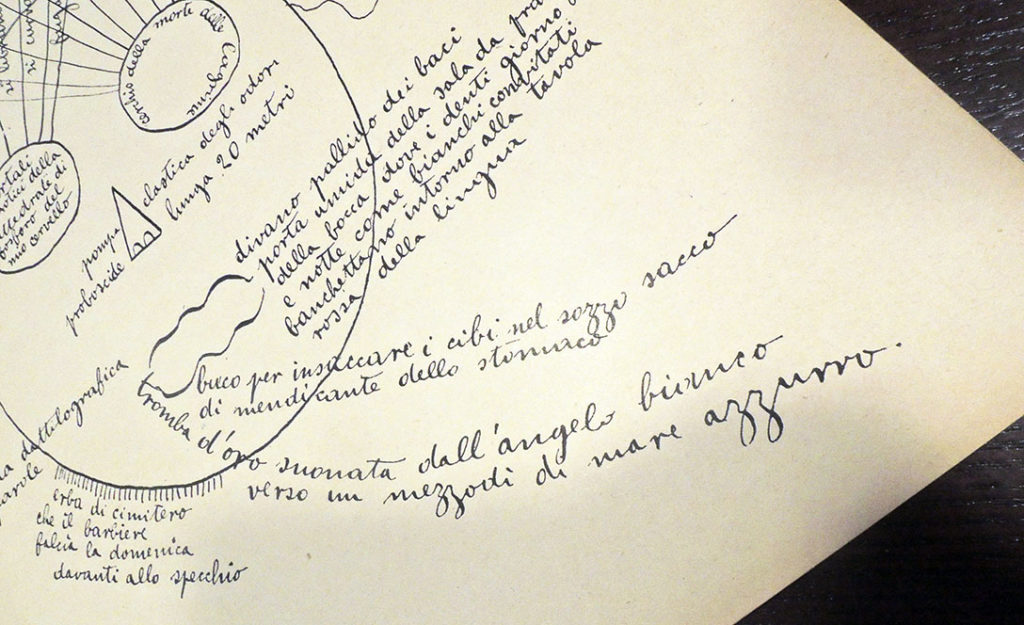

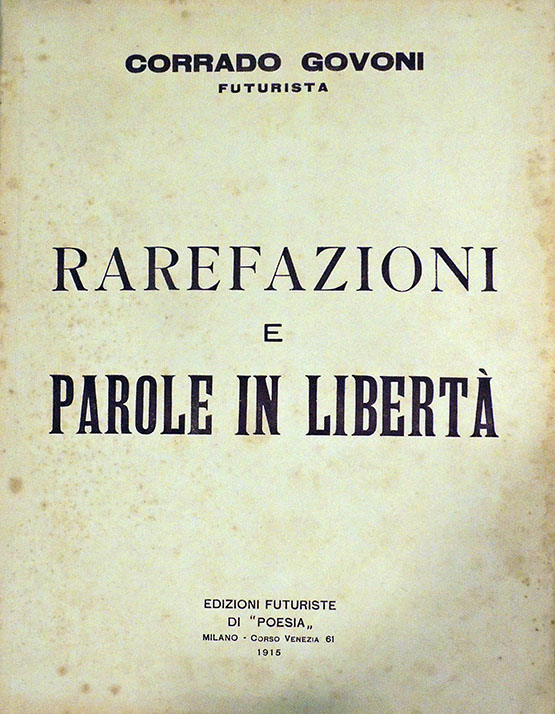

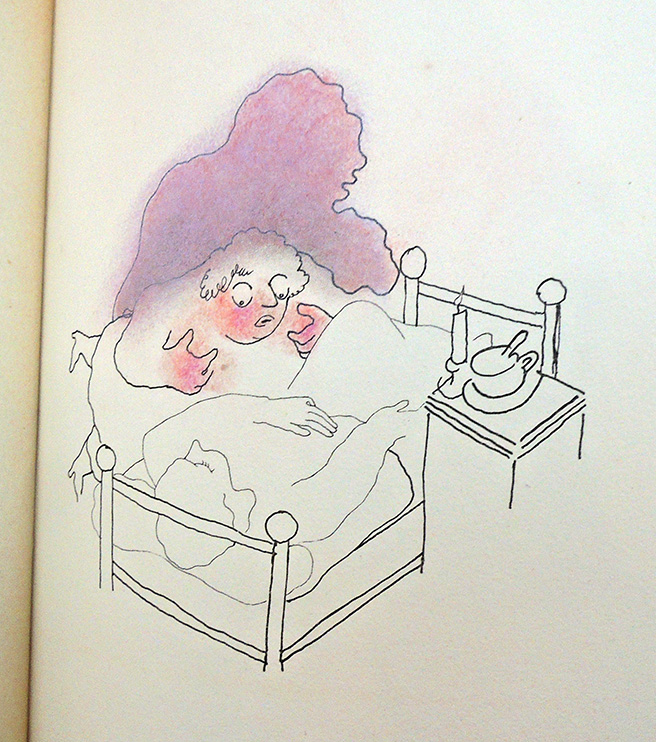

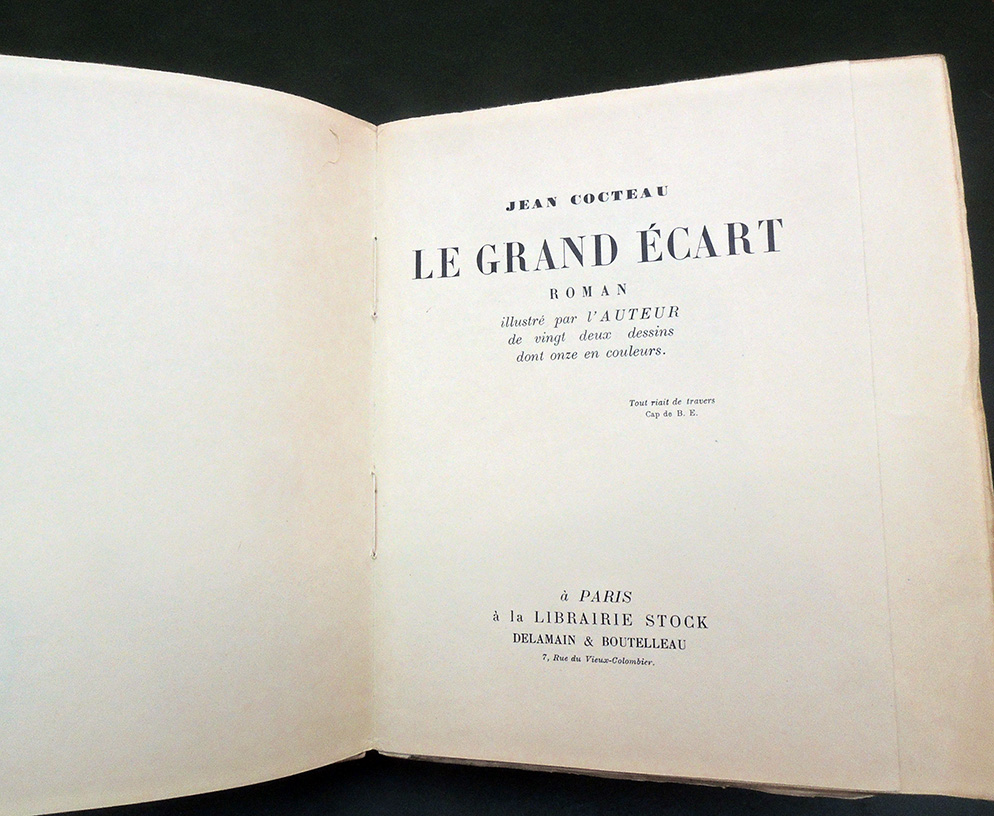

Jean Cocteau (1889-1963). Le Grand Ecart. Roman illustré par l’auteur de vingt deux dessins dont onze en couleurs (Paris: Librairie Stock, 1926). First illustrated edition, with reproductions of 22 drawings by Cocteau, 11 in color. Copy 18 of 20 on imperial Japan paper. A fine inscribed copy with a large original drawing by Jean Cocteau (profile of a male head): “à Parisot Souvenir très amical de Jean Cocteau.” Graphic Arts Collection GAX 2019- in process

Jean Cocteau (1889-1963). Le Grand Ecart. Roman illustré par l’auteur de vingt deux dessins dont onze en couleurs (Paris: Librairie Stock, 1926). First illustrated edition, with reproductions of 22 drawings by Cocteau, 11 in color. Copy 18 of 20 on imperial Japan paper. A fine inscribed copy with a large original drawing by Jean Cocteau (profile of a male head): “à Parisot Souvenir très amical de Jean Cocteau.” Graphic Arts Collection GAX 2019- in process

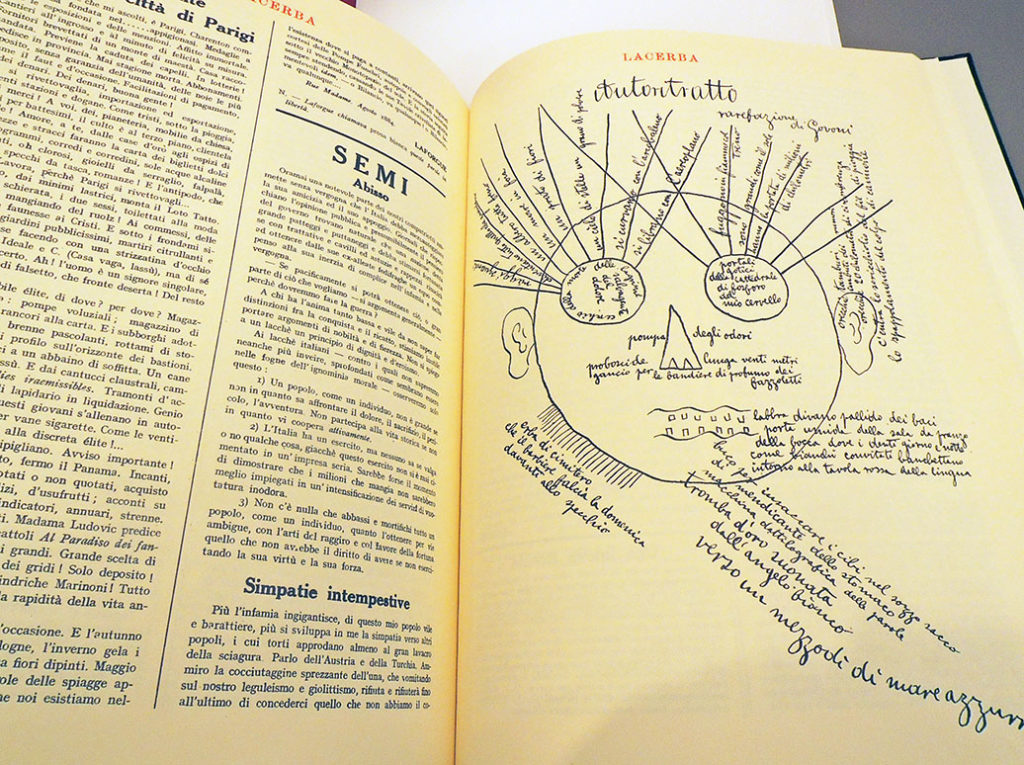

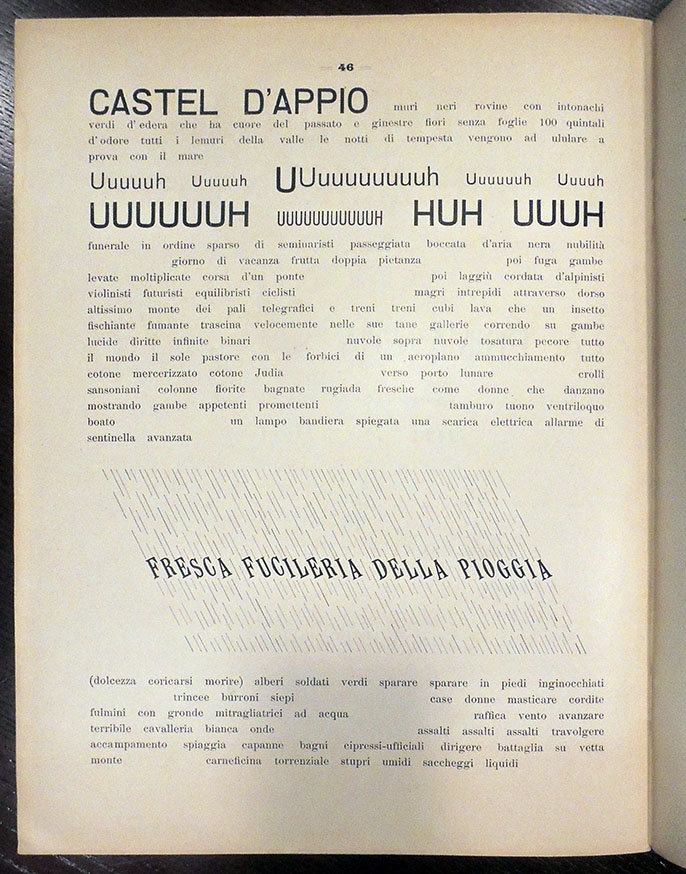

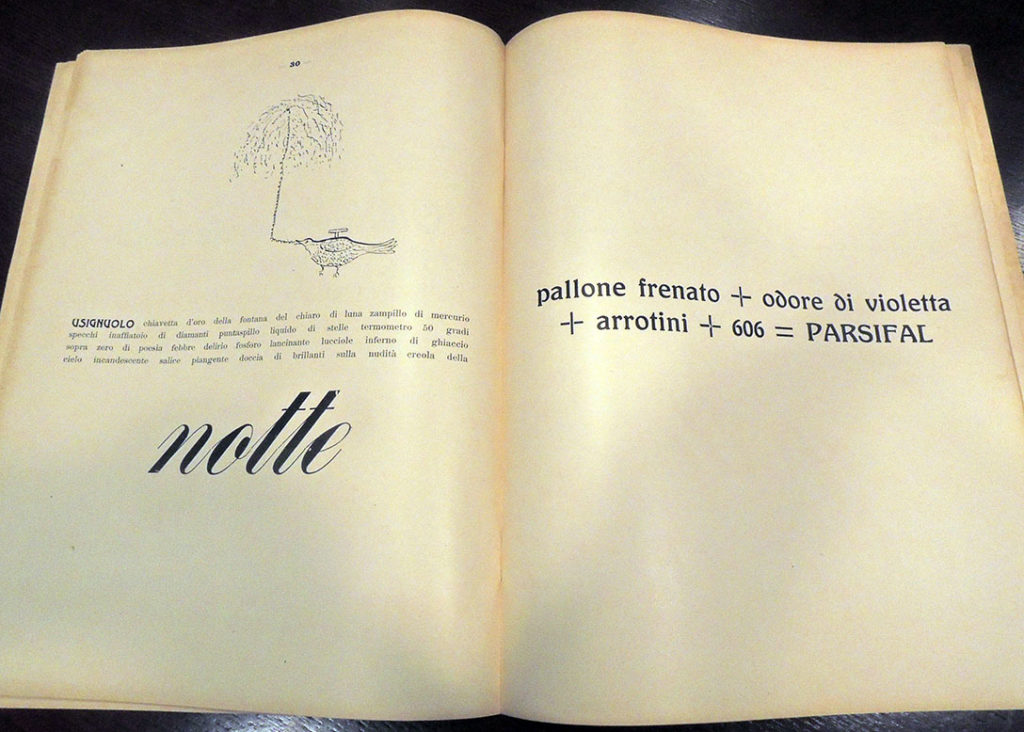

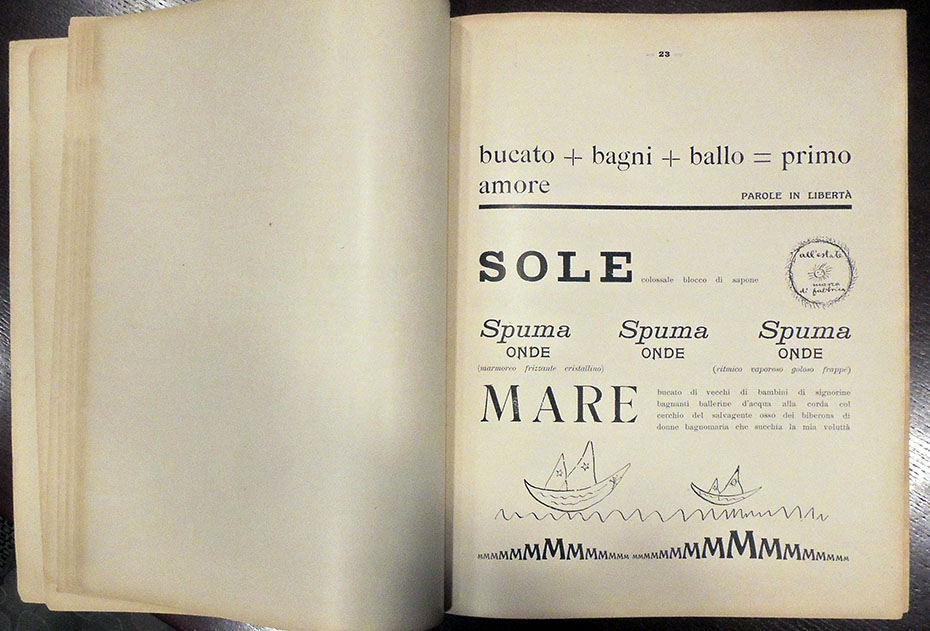

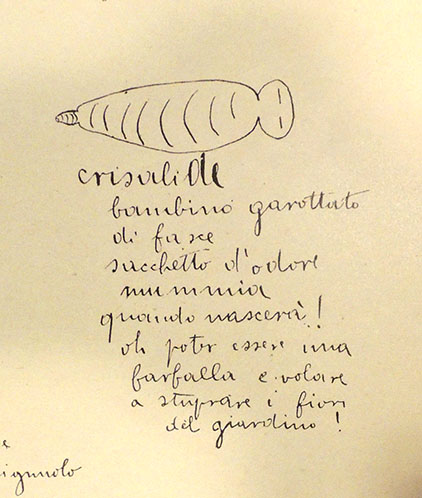

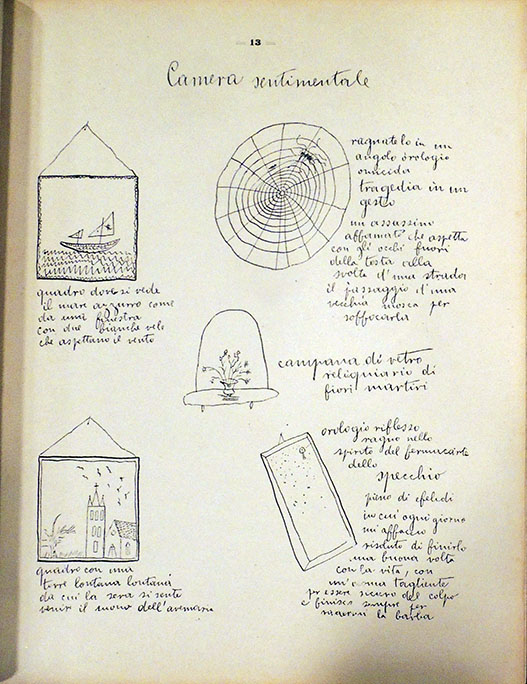

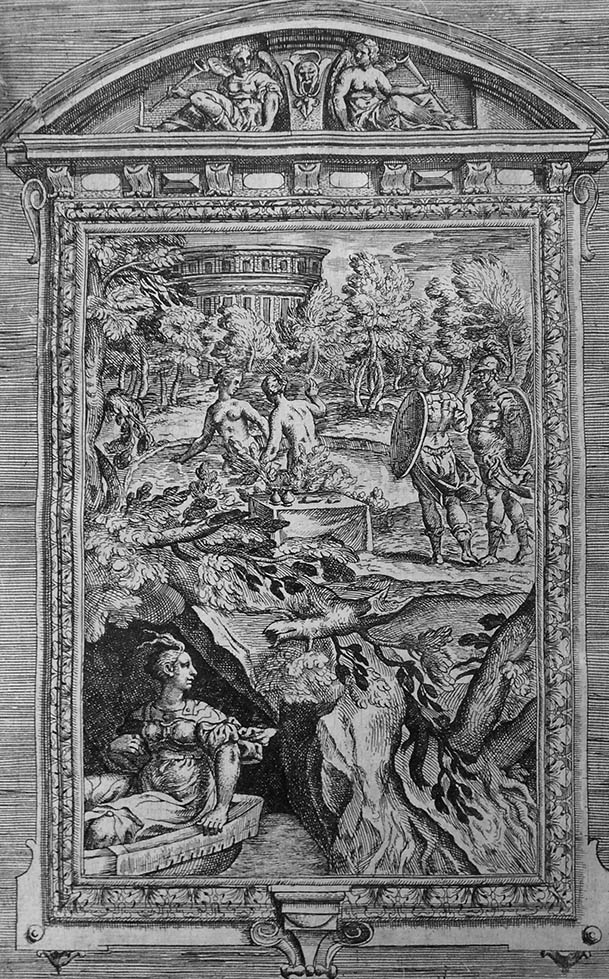

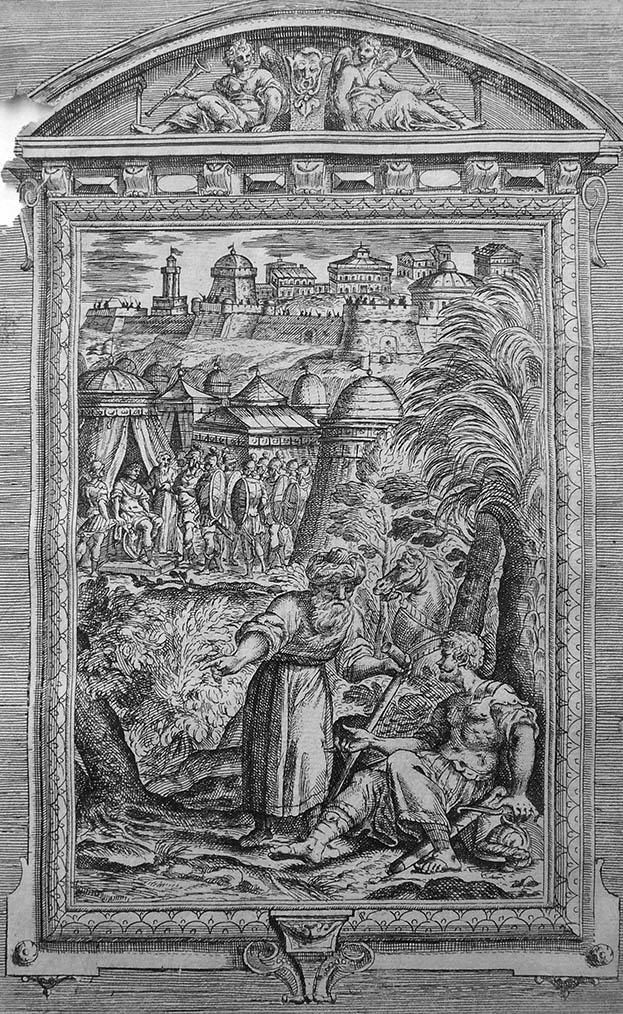

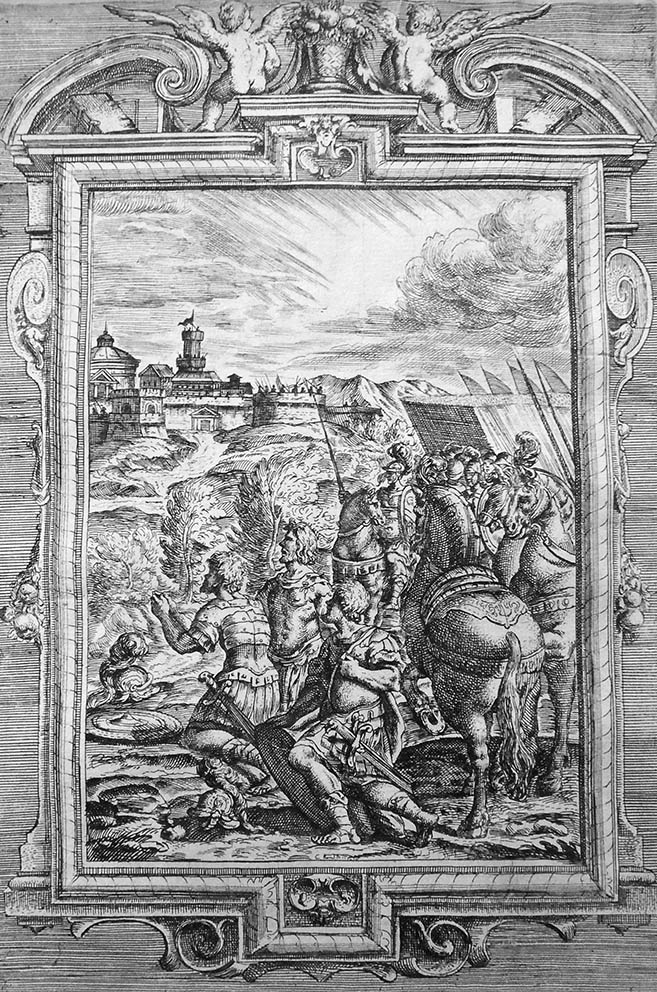

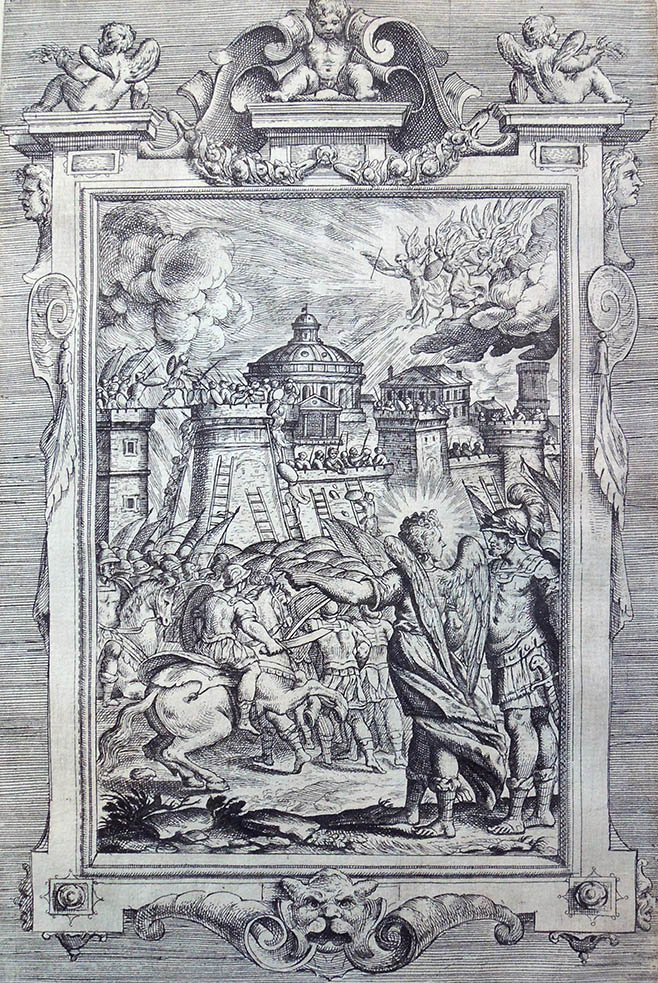

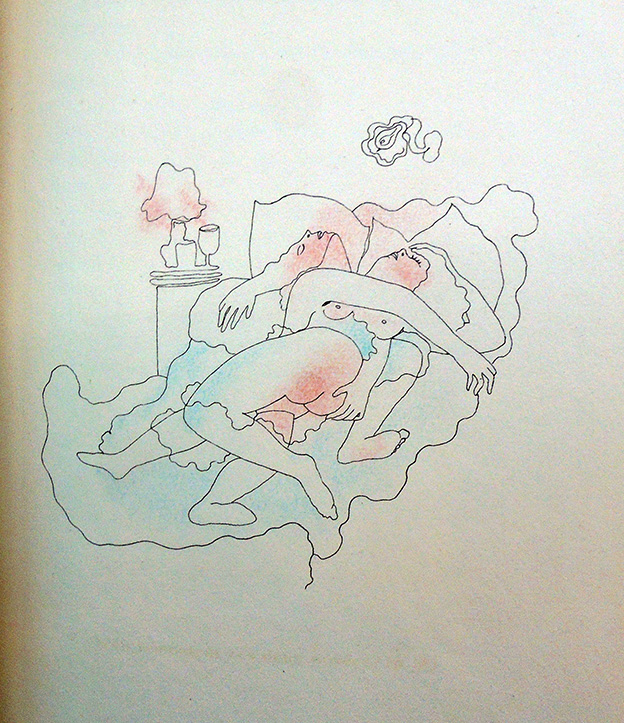

This novel has a small album of drawings bound inside between chapters. Cocteau wrote:

Ce petit roman est composé comme un album de dessins. C’est ce que nous invite à penser une lettre de Cocteau à sa mère le 19 juillet 1922 : « Tout est écrit. Il faut maintenant dessiner chaque page. La reprendre jusqu’à ce qu’elle soit ressemblante comme je fais pour mes portraits ou mes caricatures. » En réalité, à cette date rien n’est vraiment écrit : Cocteau a juste commencé, il a surtout le plan en tête (sauf l’épilogue, trouvé en octobre seulement). Et, comme l’album graphique qu’il compose en même temps (Dessins, publié en 1923), le roman se présente dans son esprit comme une suite de planches à composer l’une après l’autre. Dans ses entretiens à la radio avec André Fraigneau en 1951, Cocteau dira qu’il a composé Le Grand Écart « par petits blocs ».

This little novel is composed as an album of drawings. This is what invites us to think of a letter from Cocteau to his mother on July 19, 1922: “Everything is written. We must now draw each page. Repeat it until it looks like I do for my portraits or caricatures. In reality, at this date nothing is really written: Cocteau has just started, he has the plan especially in mind (except the epilogue, found in October only). And, like the graphic album he composes at the same time (Drawings, published in 1923), the novel appears in his mind as a series of plates to compose one after the other. In his radio interviews with André Fraigneau in 1951, Cocteau said that he composed Le Grand Écart “in small blocks”.–https://cocteau.biu-montpellier.fr/index.php?id=103

Cocteau wrote six novels: 1919: Le Potomak; 1923: Le Grand Écart; 1923: Thomas l’Imposteur; 1928: Le Livre blanc; 1929: Les Enfants terribles; and 1940: La Fin du Potomak.

During the 1920s Cocteau also devoted his time to writing several novels, a new genre for him. These novels are usually concerned with protagonists who cannot leave their childhoods behind them. In Le Grand Ecart, for example, Jacques Forestier finds that beauty always brings him pain, a pattern established when he was a child.

As a young man, the pattern continues when he loses his first love to another man, leading Jacques to attempt suicide. Germaine Bree and Margaret Guiton note in The French Novel from Gide to Camus that Jacques is “the most directly autobiographical of Cocteau’s fictional characters.” In addition, as McNab pointed out, the novel anticipates Cocteau’s later obsession with childhood. — https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poets/jean-cocteau