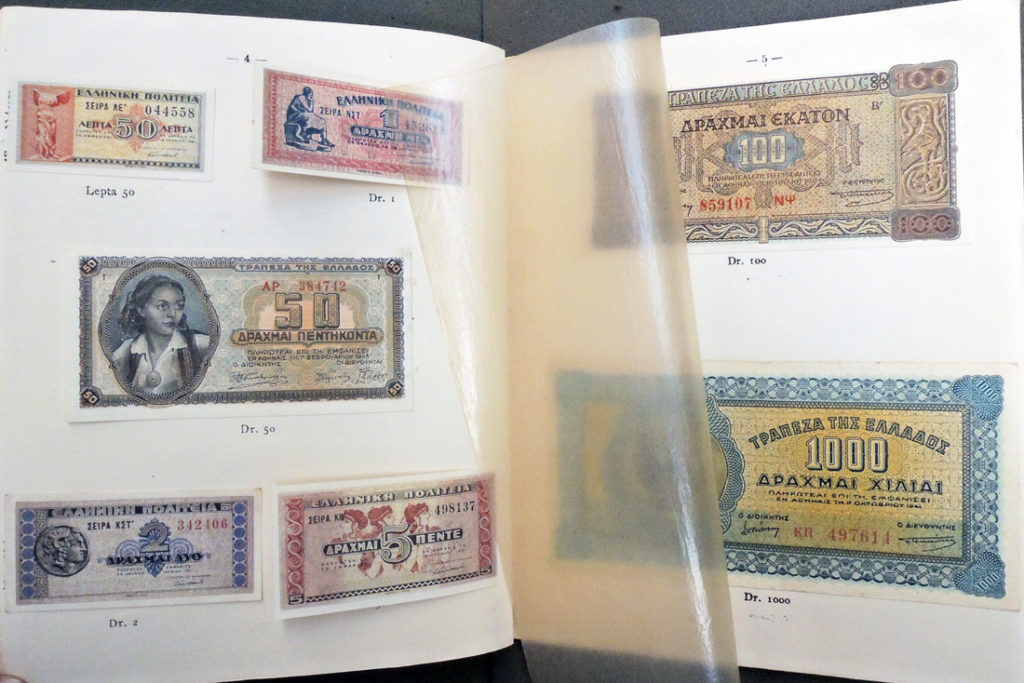

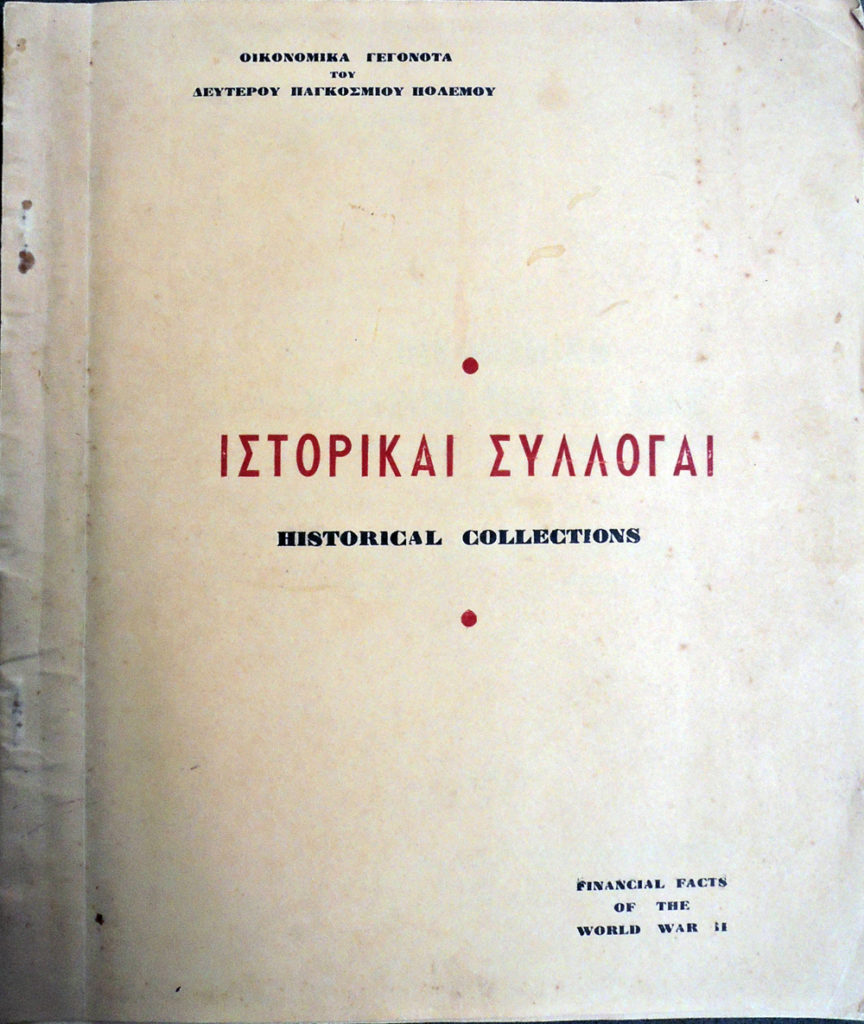

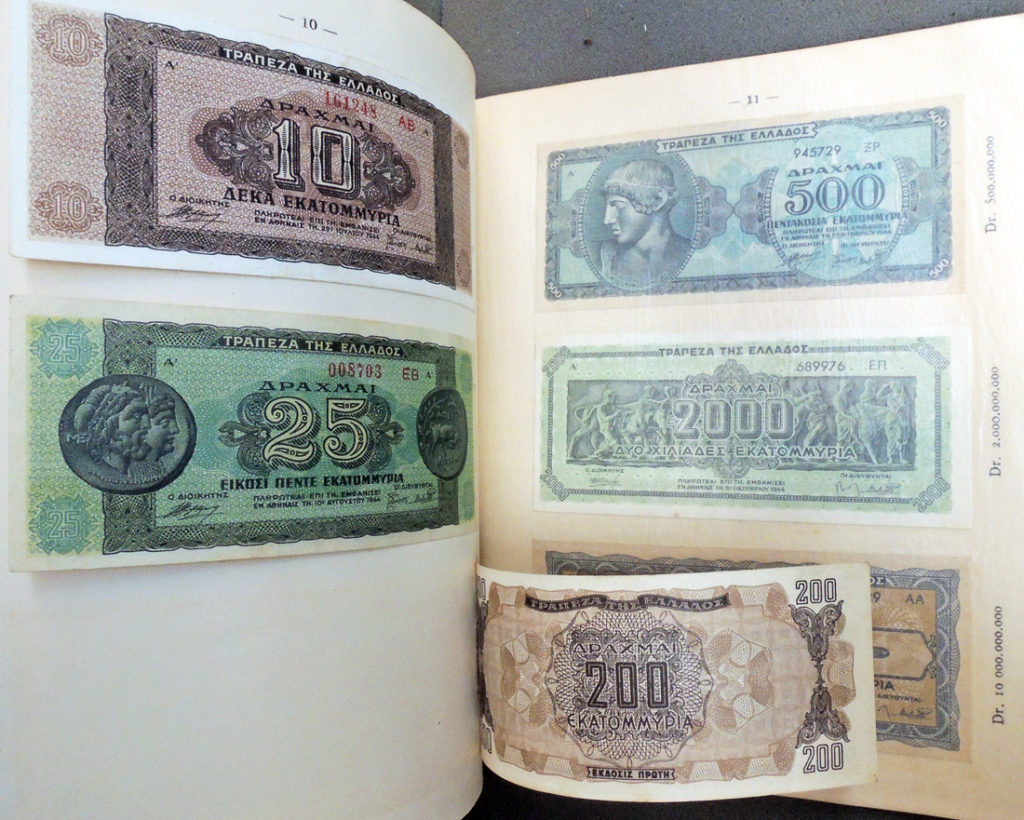

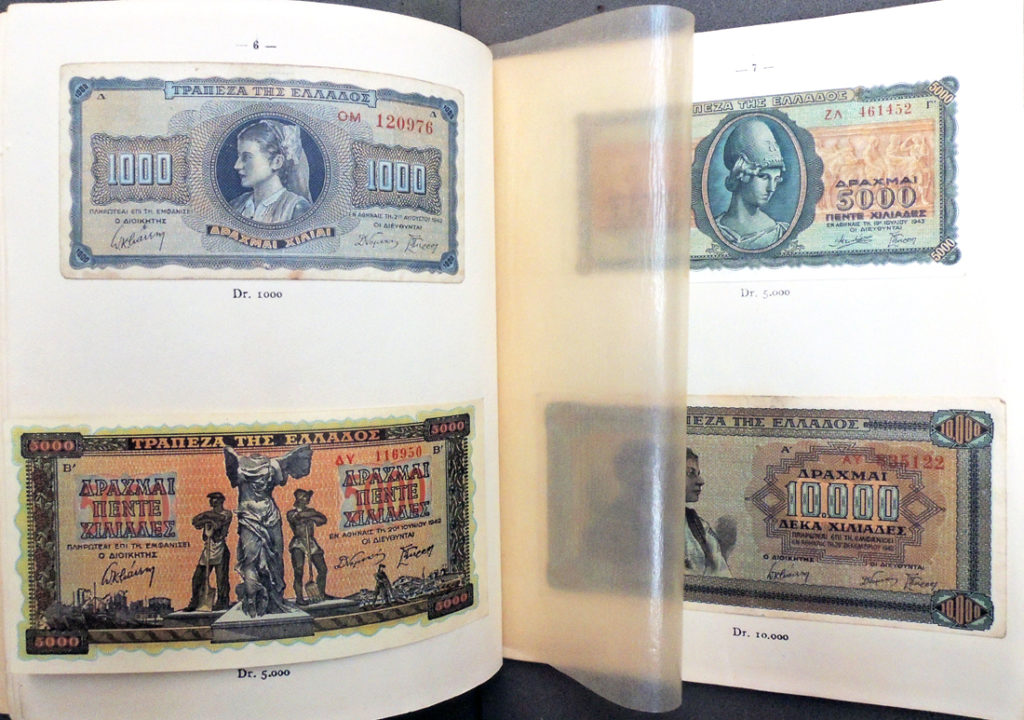

Thanks to those who responded with suggestions about where to find money in books. Dimitri Gondicas, Stanley J. Seeger Director of the Center for Hellenic Studies, The Council of the Humanities, and Lecturer in Classics at Princeton University pointed to this volume with 24 banknotes mounted on 9 pages. “The banknotes inside,” he writes, “are testimony of the rampant inflation during the WWII German Occupation of Greece.”

The anonymous author writes: “For us Greeks and the future generations the collection of bank notes and paper money put into circulation by the Italians and Germans will be a horrible nightmare and an uncontradicted proof of the hardships that our cruelly tried country has gone through. The Institute of Mining Credit worked out this collection as a symbol for one of Greece’s most heroic eras, which rivals its previous ones in magnitude. This collection represents one of the most important financial events of the most devastating war the world has ever gone through.”

Unfortunately, the bank notes are so gently tipped into the volume, many are already beginning to separate from the page. All except the final example are legitimate and rare.

Unfortunately, the bank notes are so gently tipped into the volume, many are already beginning to separate from the page. All except the final example are legitimate and rare.

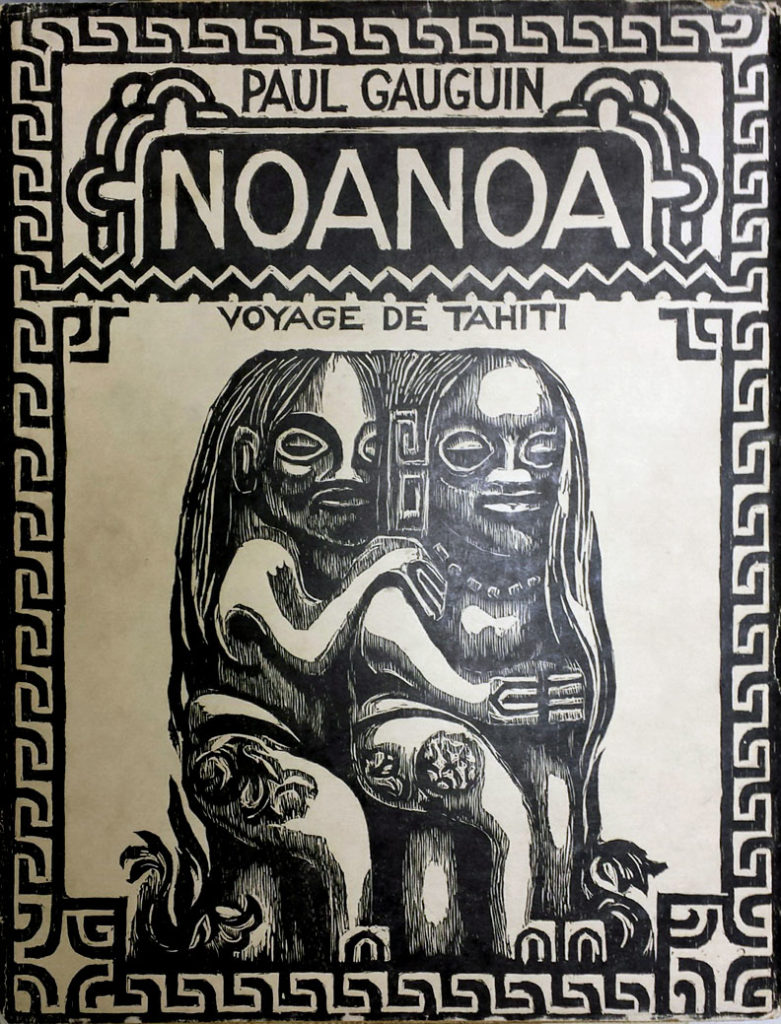

Oikonomikē syntrivē tēs Hellados, Aprilios 1941-Noemvrios 1944 = Financial Breakdown of Greece, April 1941-November 1944 (Athens, Greece: The Establishment of Mining Credit Corporation, Scientific Section–Historical Collections, [1945?]). 2nd ed. At head of title: Hotan hoi Nazi kataktoun = When the Nazis conquer. On cover: Oikonomika gegonota tou deuterou Pankosmiou Polemou = Financial Facts of the World War II. Ex 2014-0277Q