On December 8, 1896, The Daily Princetonian published a short note:

A new magazine which is creating quite a stir among the lovers of current literature is a monthly periodical called John-A-Dreams. This little and attractive magazine was started last June and has been issued monthly since then and its final success is assured by the large sale which it has attained. Its form is novel which adds much to its popularity.

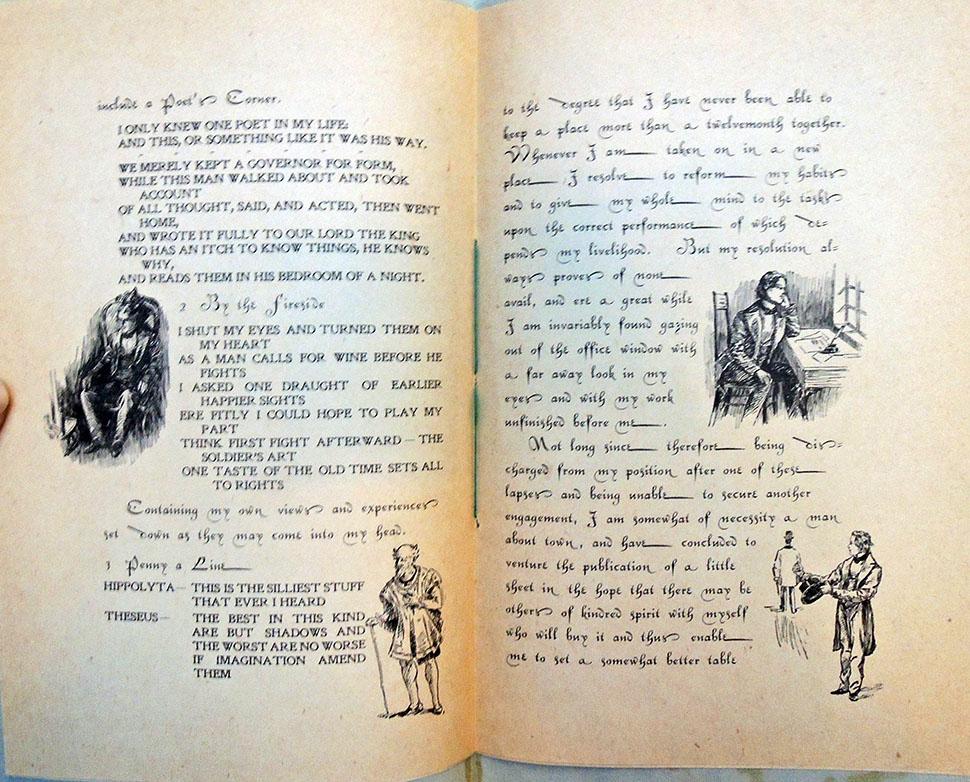

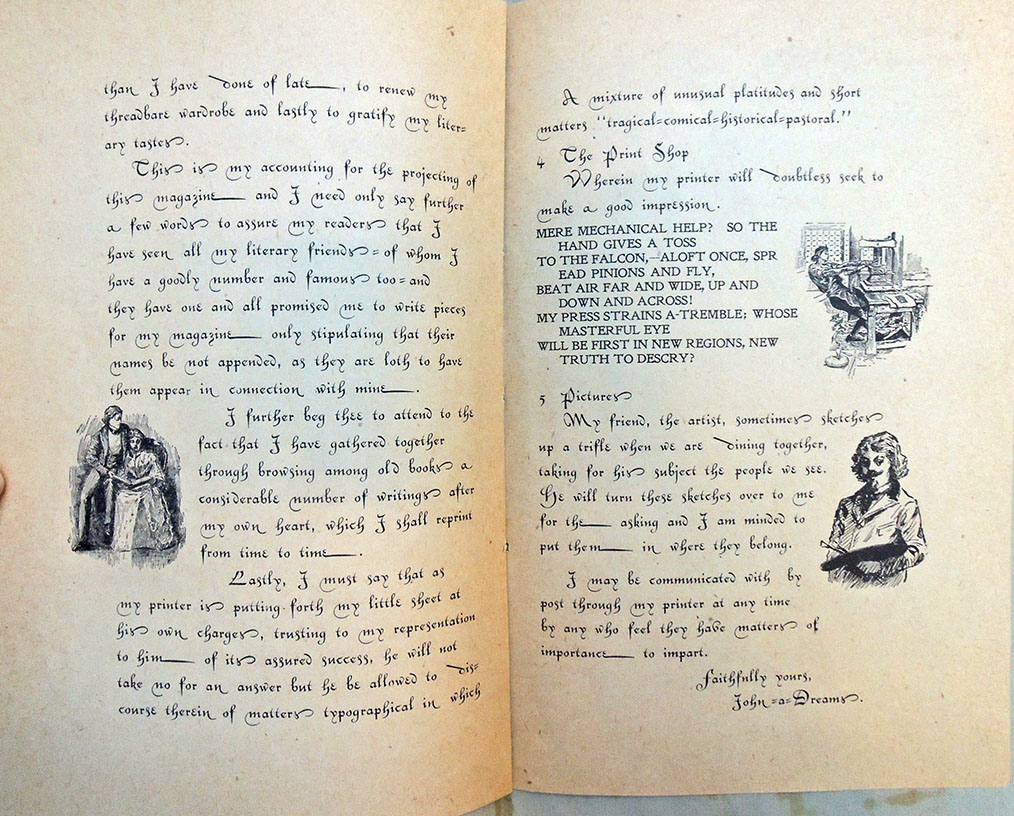

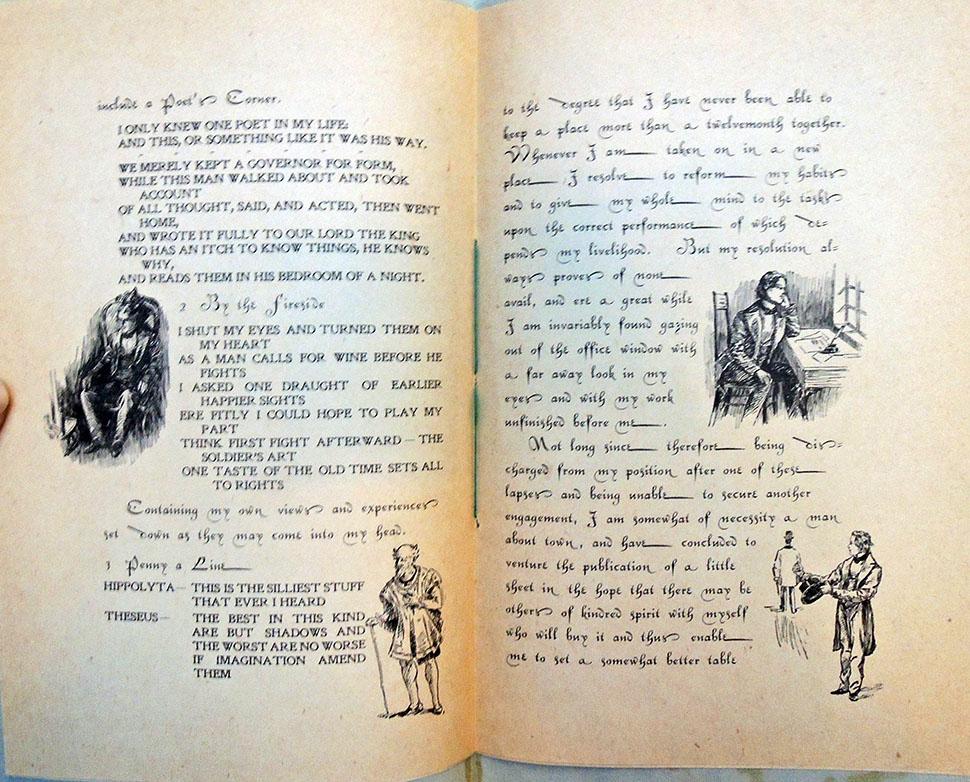

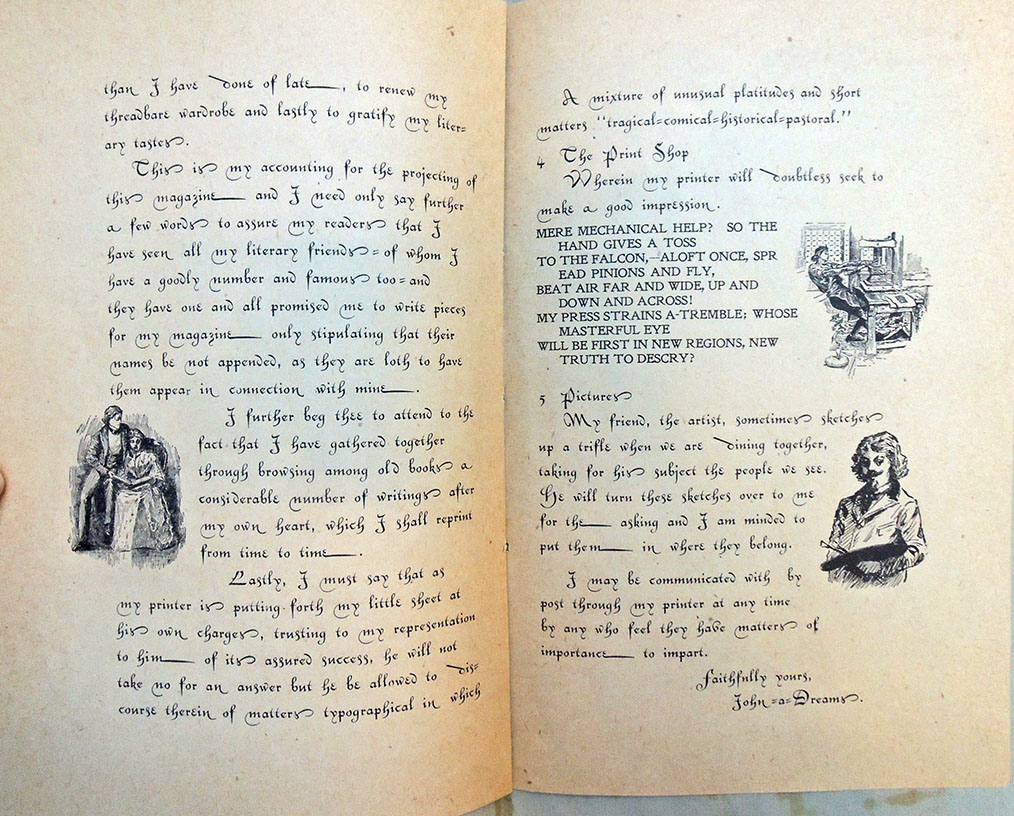

It generally contains several short stories which are marvels for their freshness and simplicity as well as for the pleasing manner in which they are told. Besides this there are in each number several poems which compare favorably with the present day verse. The two departments “The Artistic Standpoint” and “By The Fireside are of especial interest. The former is a series of criticisms which show a keen grasp of the subject at hand. This magazine is edited and published by Robert Sloss of the class of ’93. The cover design, as well as all parts of the magazine, is very artistic. —Daily Princetonian 21, No. 109 (8 December 1896).

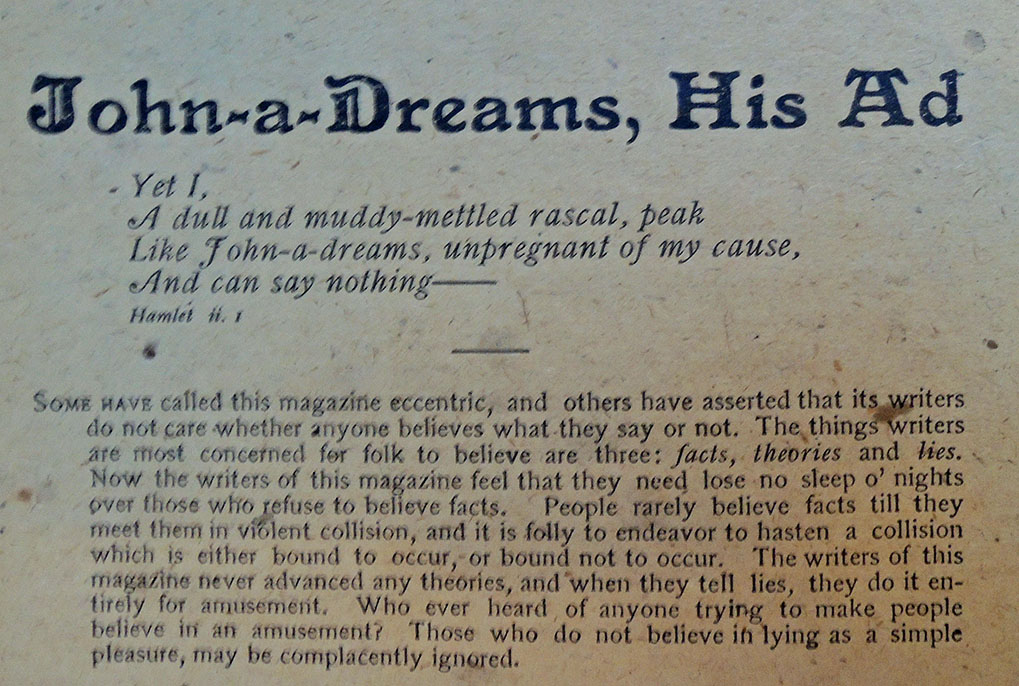

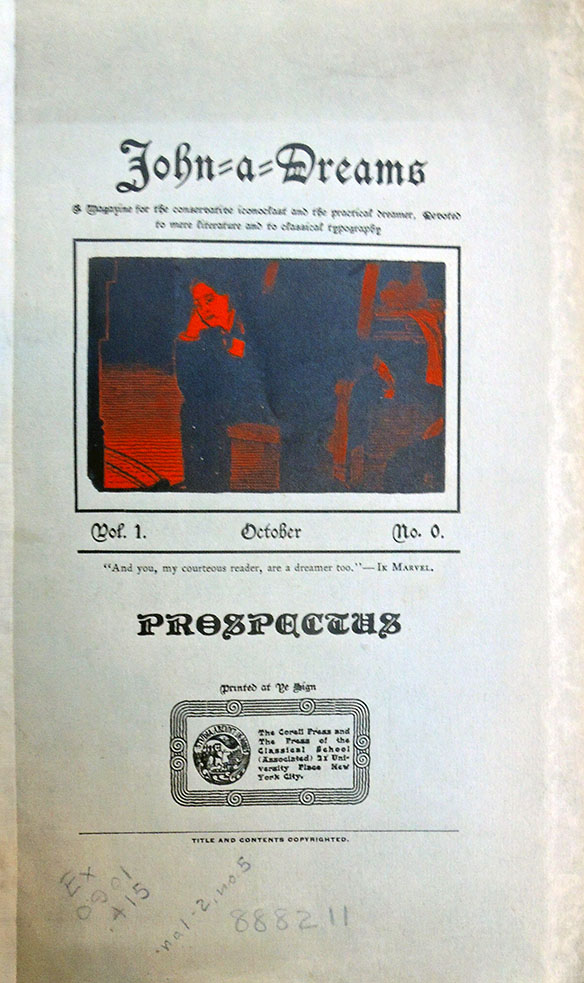

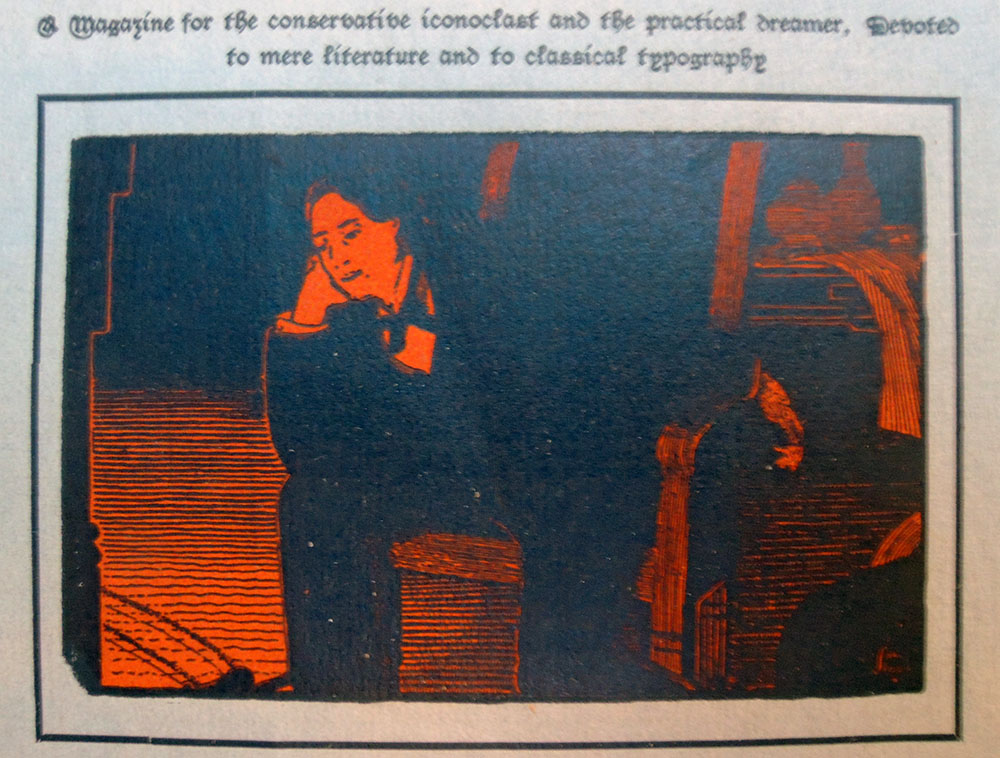

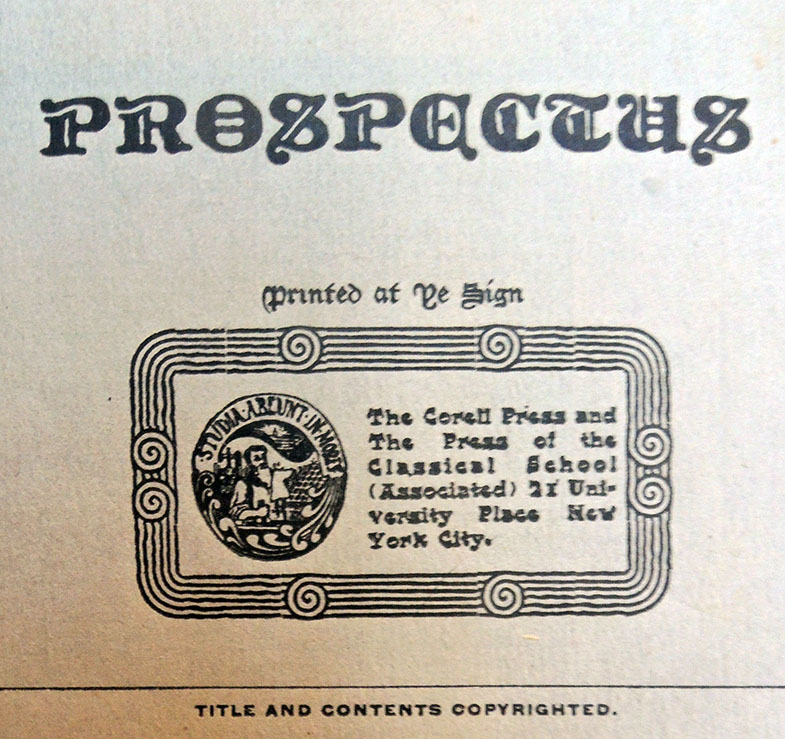

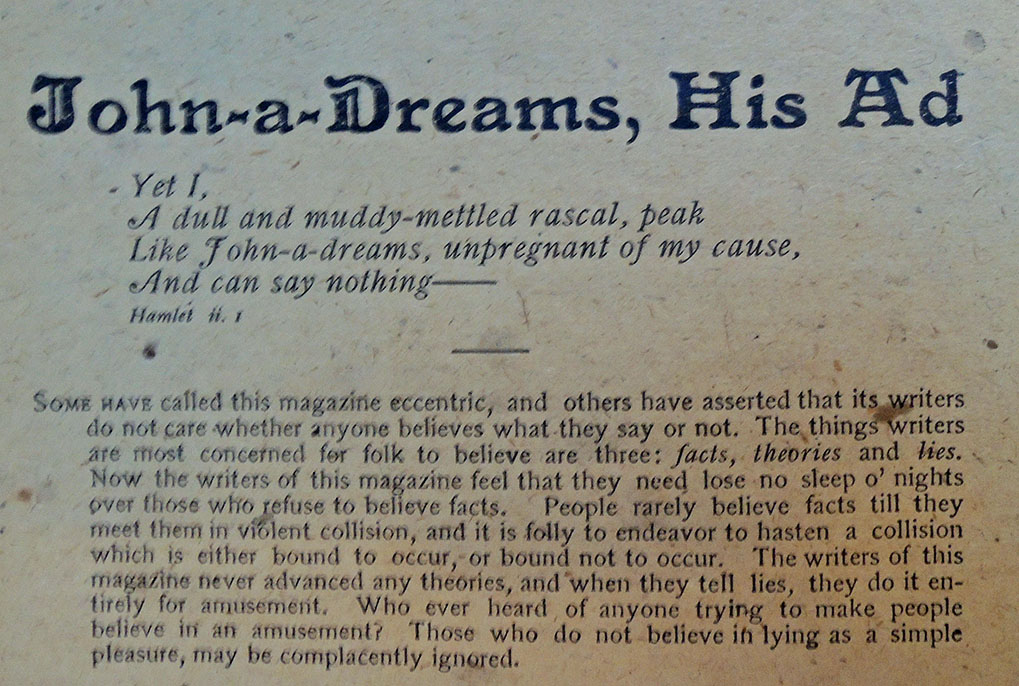

John-a-Dreams: A Magazine for the Conservative Iconoclast and the Practical Dreamer, Devoted to Mere Literature and to Classical Typography.

John-a-Dreams: A Magazine for the Conservative Iconoclast and the Practical Dreamer, Devoted to Mere Literature and to Classical Typography.

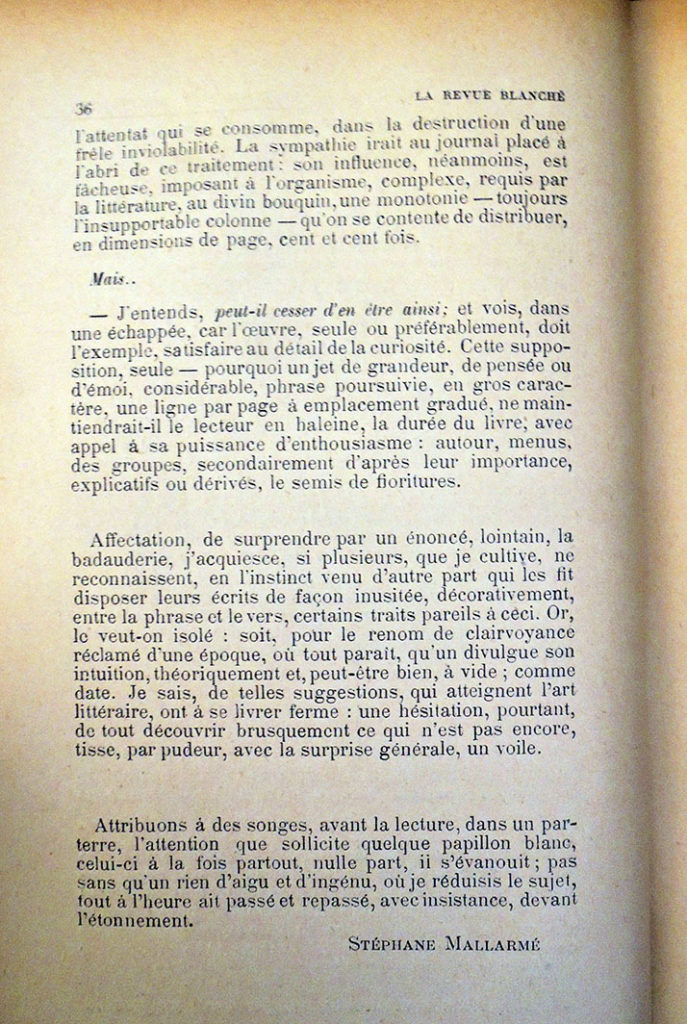

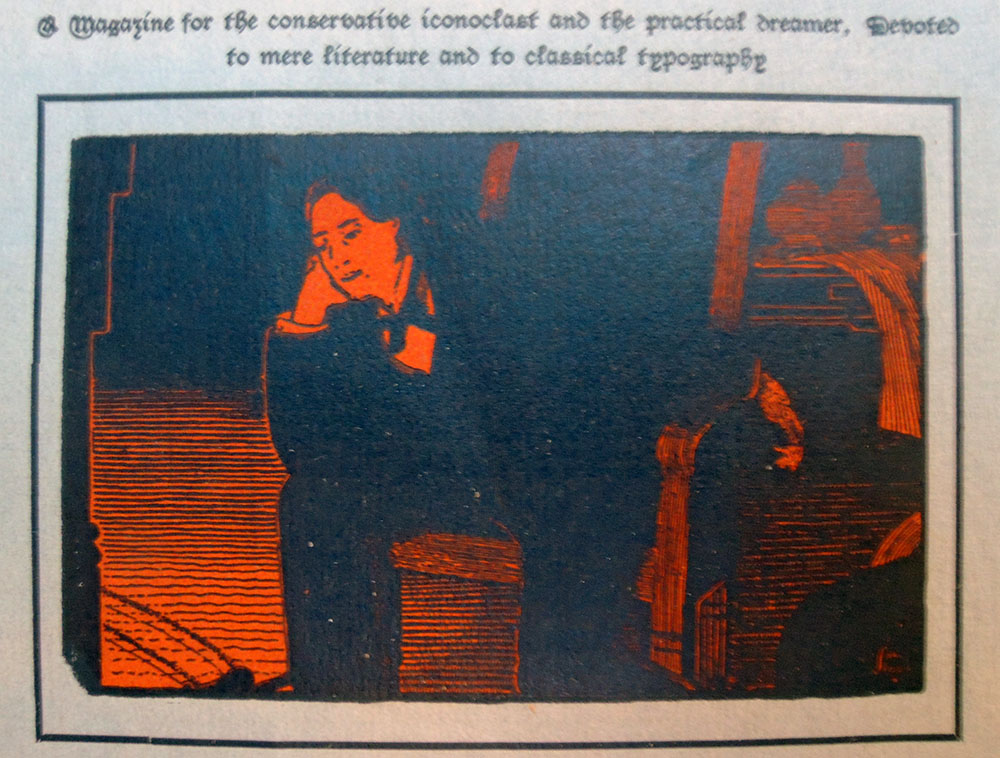

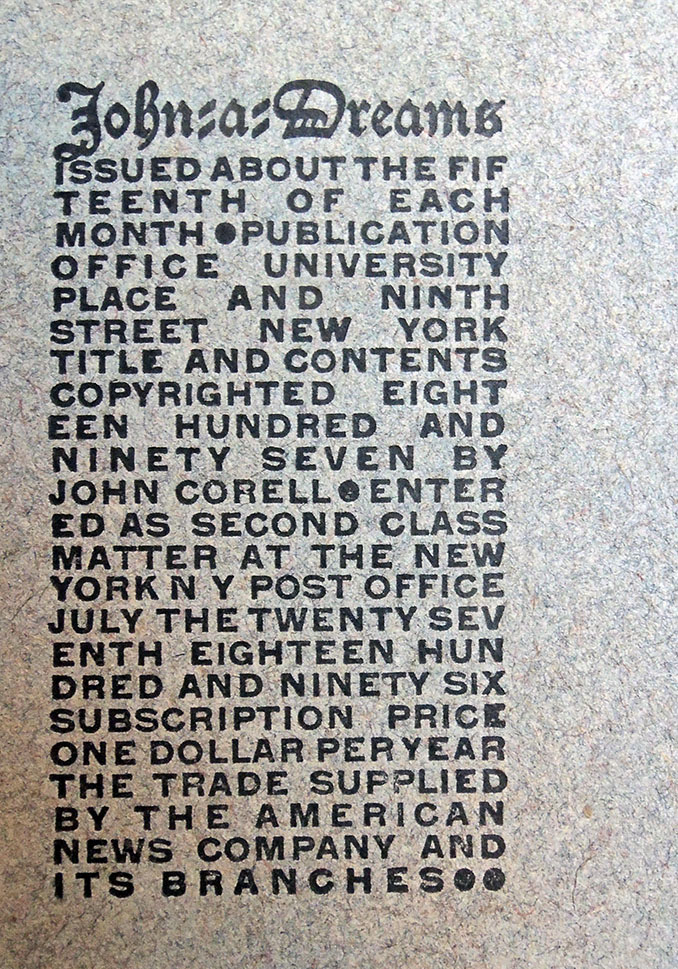

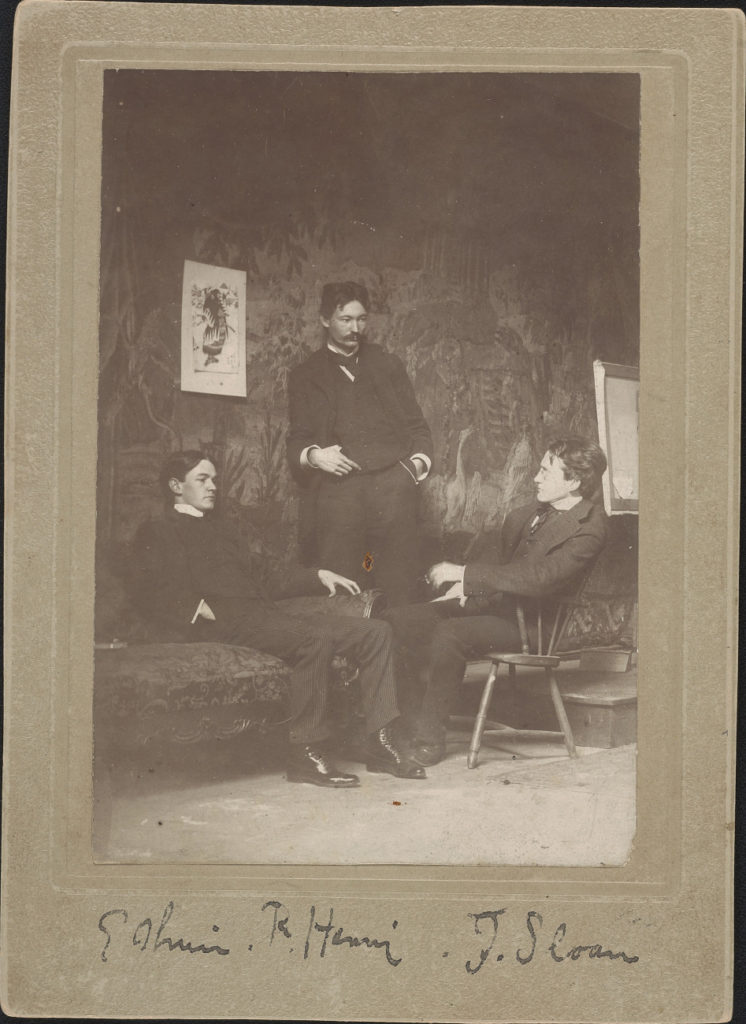

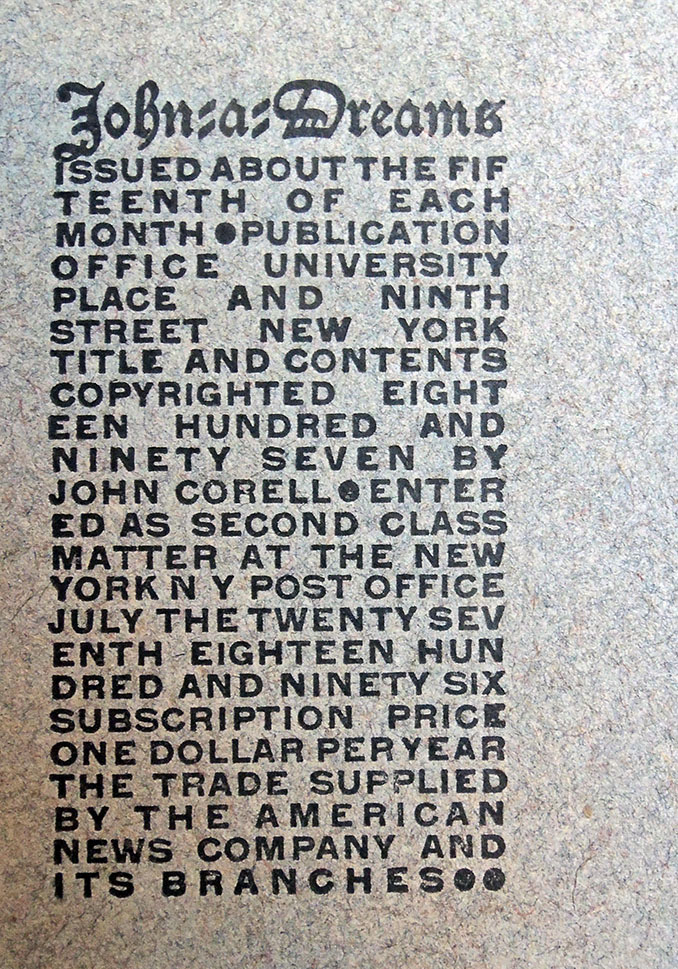

After graduation, Robert T. Sloss (1872-1920, Princeton Class of 1893) moved to Greenwich Village where he formed a partnership with John J. Corell (1873-1954) to found the Corell Press and the monthly magazine John-a-Dreams. Their staff artist and poet was Sloss’ classmate Booth Tarkington (1869-1946, Princeton class of 1893) and the cover image of a dreaming man was drawn by the artist John Sloan (1871-1951), still living in Philadelphia but already a well-known illustrator. At the time, Sloan had left The Philadelphia Inquirer to join the art department of The Philadelphia Press, where he only worked afternoons and evenings, leaving his mornings free to paint and take on other commissions.

While Tarkington was writing one-act plays, his college classmate Robert Sloss launched in Greenwich Village a “little” magazine called John-a-Dreams. The publication appeared only seven times between August, 1896, and May, 1897, but during its short life Tarkington, the unpaid staff artist, contributed prose, poetry, and drawings “The Kisses of Marjorie,” for instance, first appearing there.

…Most of Tarkington’s contributions to John-a-Dreams are unimportant, though they illustrate a poetic preoccupation that began at the age of thirteen and lasted till he was thirty. Throughout the Nineties he composed poems, and only after his first novel was published did he foreswear verse.

…Then he abandoned poetry completely, except when his fictional characters occasionally were moved to lyric expression. Before 1899, however, about two dozen of his poems appeared in print, many in Princeton publications, a handful in the Indianapolis Journal, and three in Sloss’ magazine.

–James Leslie Woodress, Booth Tarkington: Gentleman from Indiana (Philadelphia; New York: Lippincott, 1955).

For more information, the archive of Corell Press is held by Wichita State University: MS 89-20, where they note:

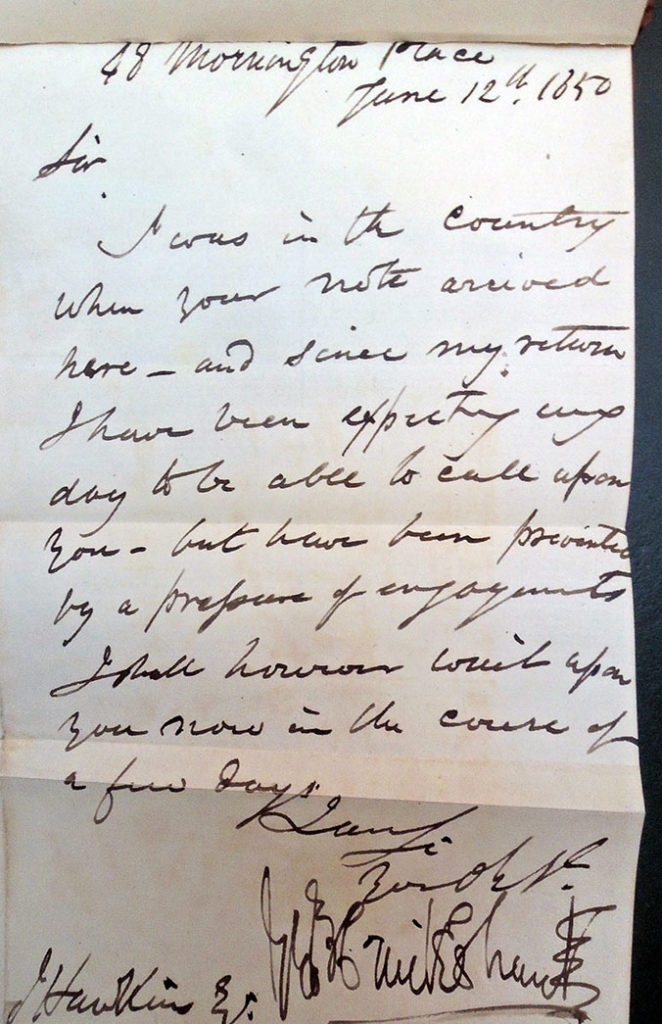

The collection consists of selected material of Sloss (Princeton Class of 1893): correspondence, printed copies of two of his articles, and newspaper clippings. Correspondence includes letters of recommendation for Sloss from Princeton faculty (1891-1893) and other letters from such notables as Edmund Gosse and Theodore Roosevelt, written to Sloss in London when he was a journalist there during World War I. …Most of the correspondence and literary works are attributed to Booth Tarkington; however, some also concern Corell’s magazine, John-a-Dreams. Correspondents include Edward W. Bryant, Robert T. Sloss, Carolyn Wells, Kenneth Brown, St. George Best, and Barton Currie. The collection also contains copies of the little magazine, John-a-Dreams, including its prospectus and inaugural issues.

—http://specialcollections.wichita.edu/collections/ms/89-20/89-20-A.HTML

Booth Tarkington, Tantor Media

Booth Tarkington, Tantor Media

John-a-Dreams (New York: Corell Press and the Press of the Classical School (Associated), 1896-1897). Vol. 1. no. 1 (July 1896)- v. 2, no. 6 (June 1897). Rare Books 0901.415 v.1-2, no.5

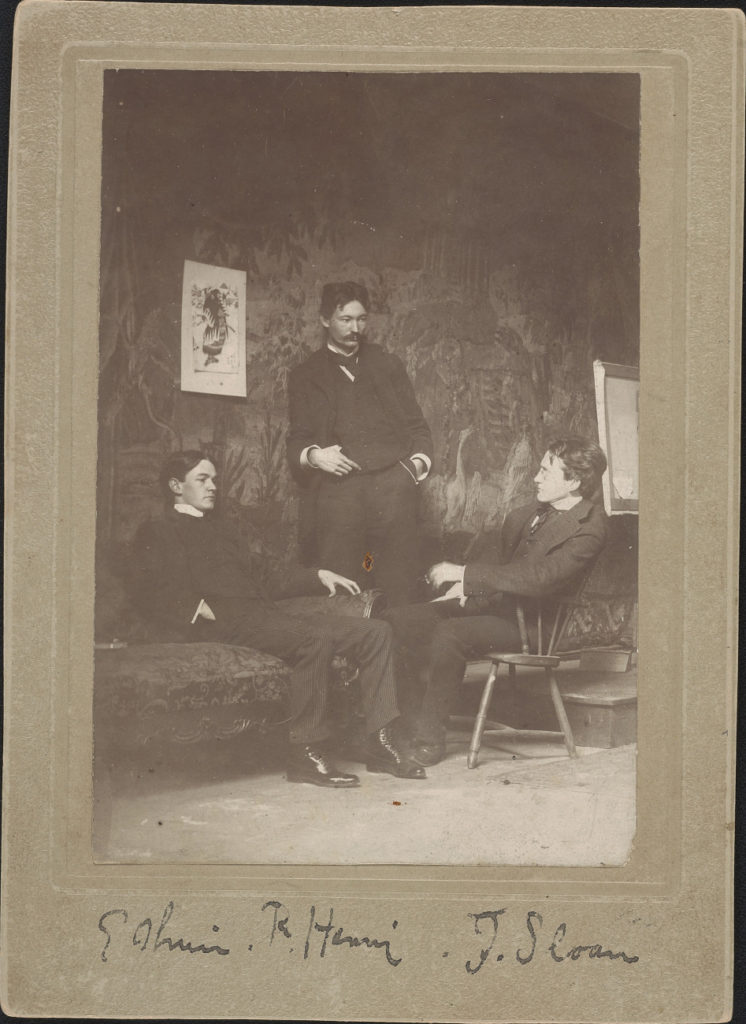

Everett Shinn, Robert Henri and John Sloan, ca. 1896. Photograph shows the three men in Henri’s Philadelphia studio; a few years later all three had moved to New York. Published in: Archives of American Art Journal v. 19, no. 2, p. 3; v. 35, no. 1-4, p. 99

Everett Shinn, Robert Henri and John Sloan, ca. 1896. Photograph shows the three men in Henri’s Philadelphia studio; a few years later all three had moved to New York. Published in: Archives of American Art Journal v. 19, no. 2, p. 3; v. 35, no. 1-4, p. 99

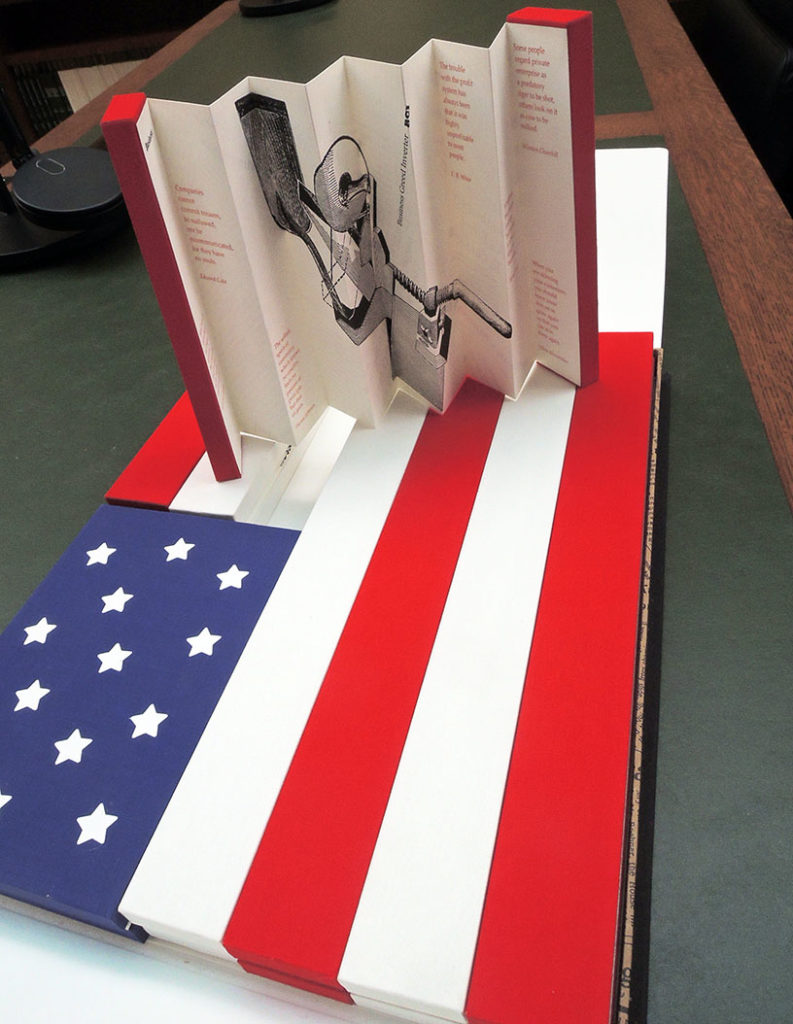

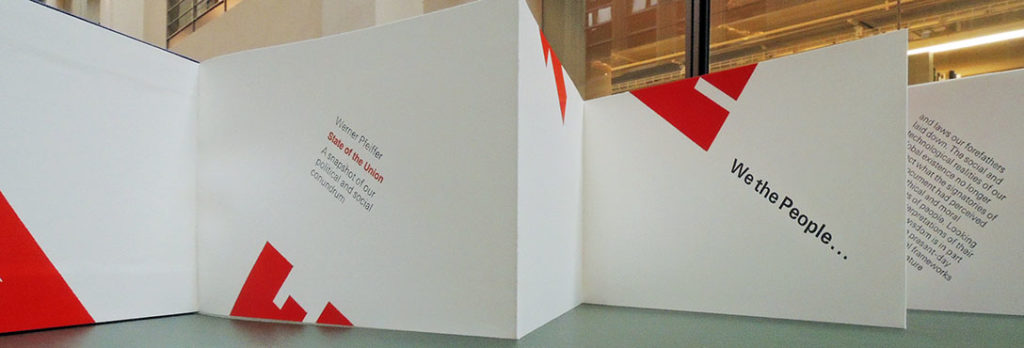

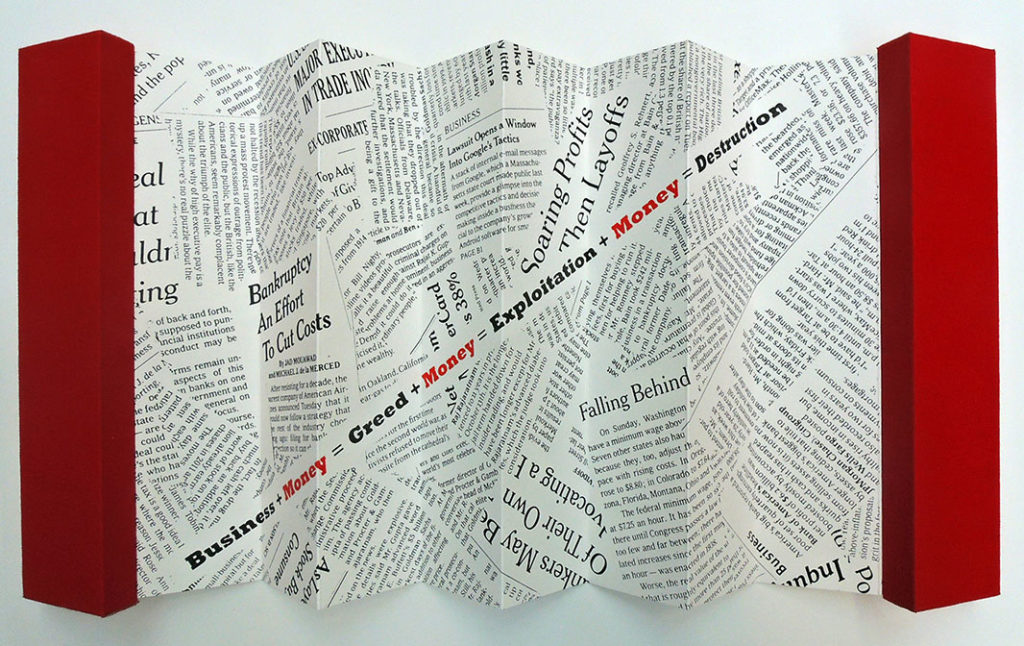

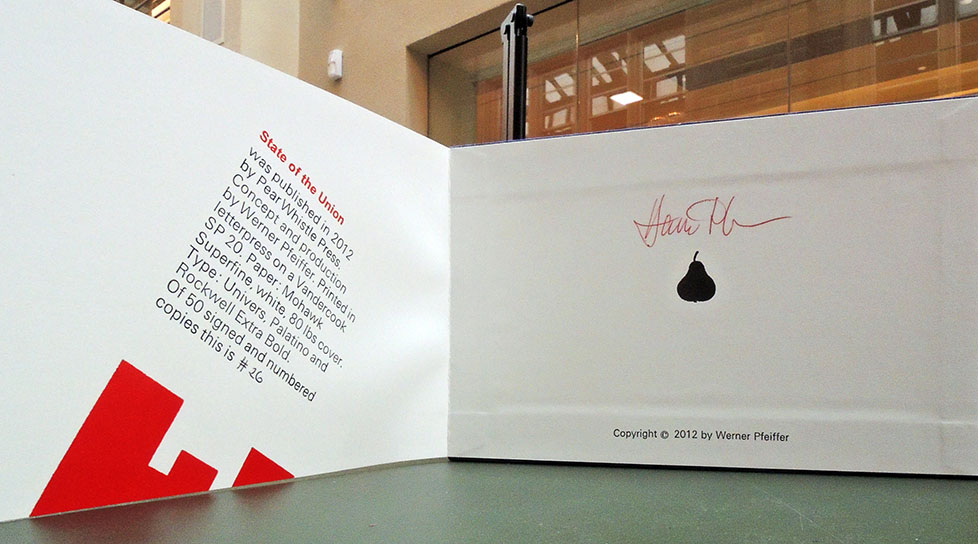

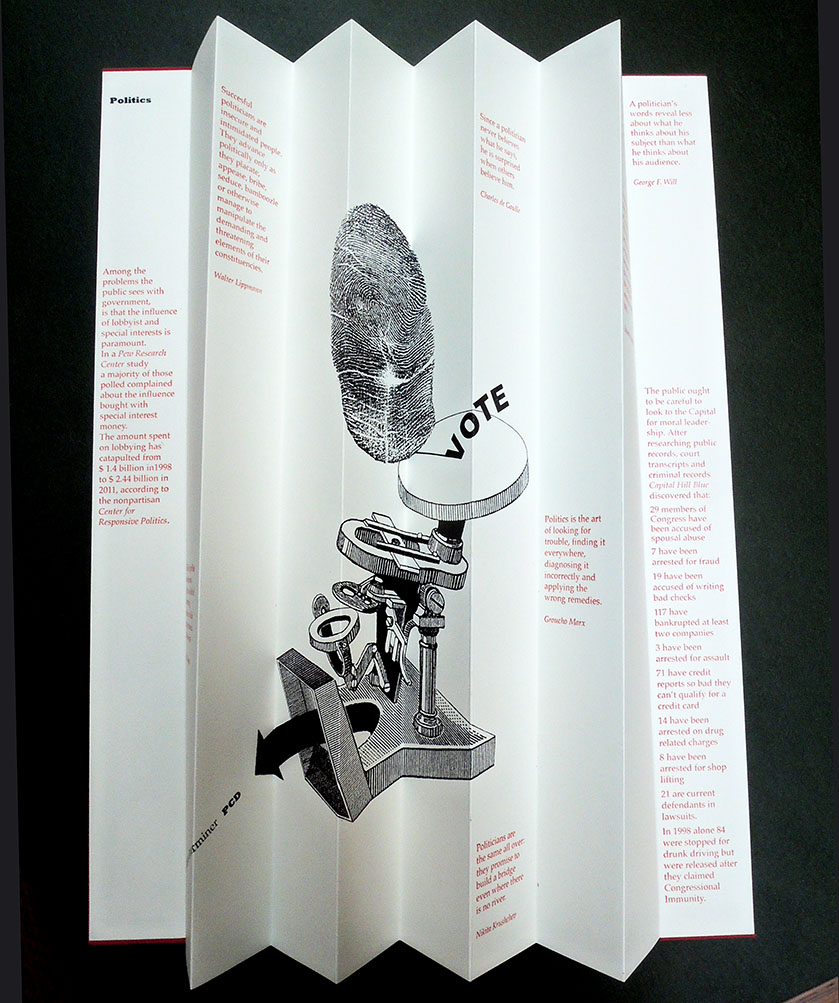

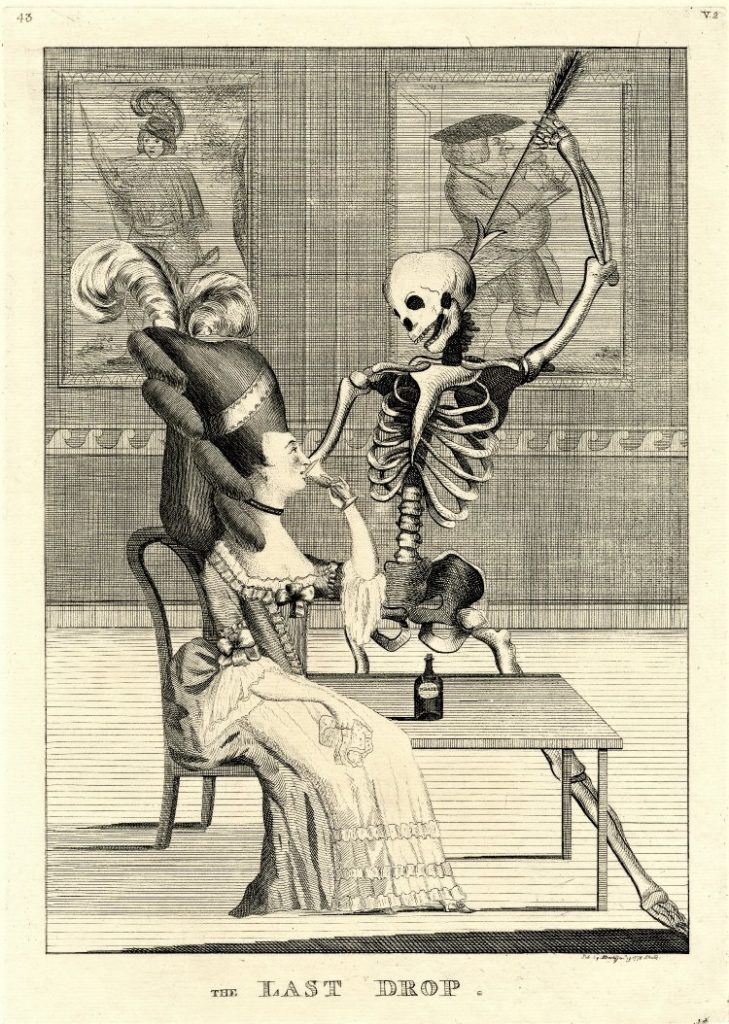

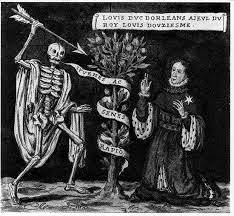

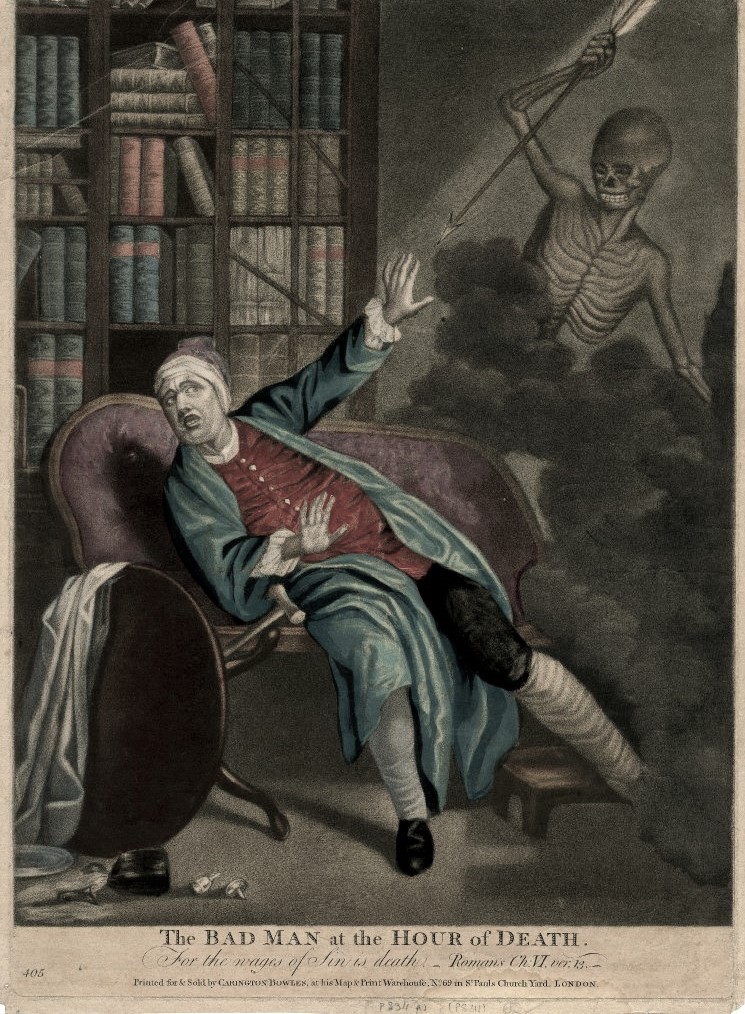

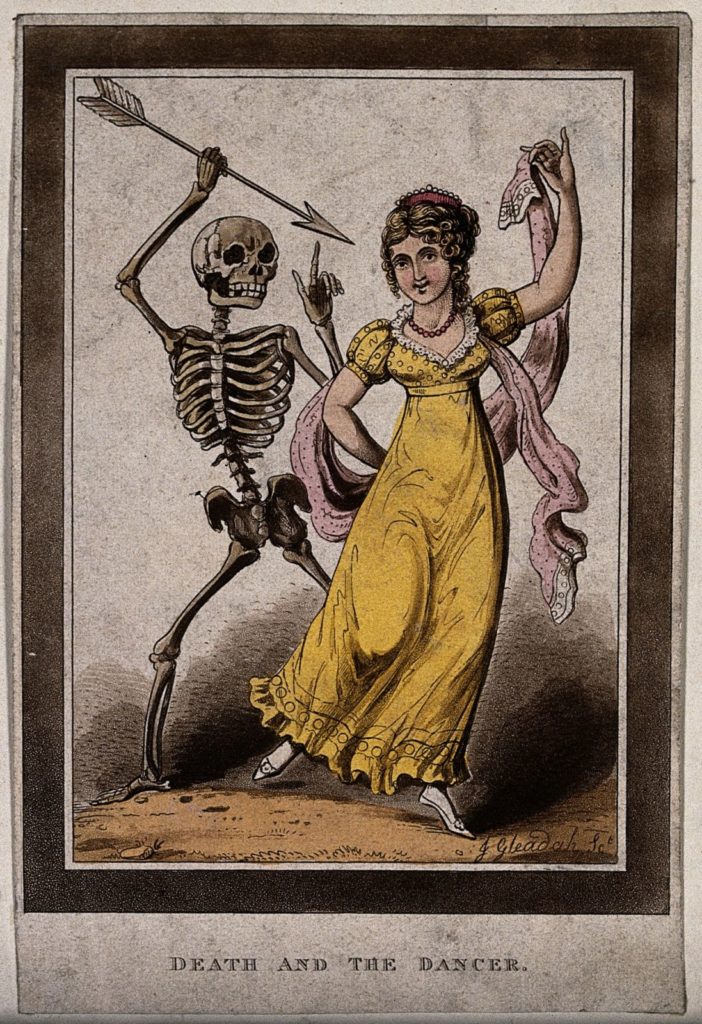

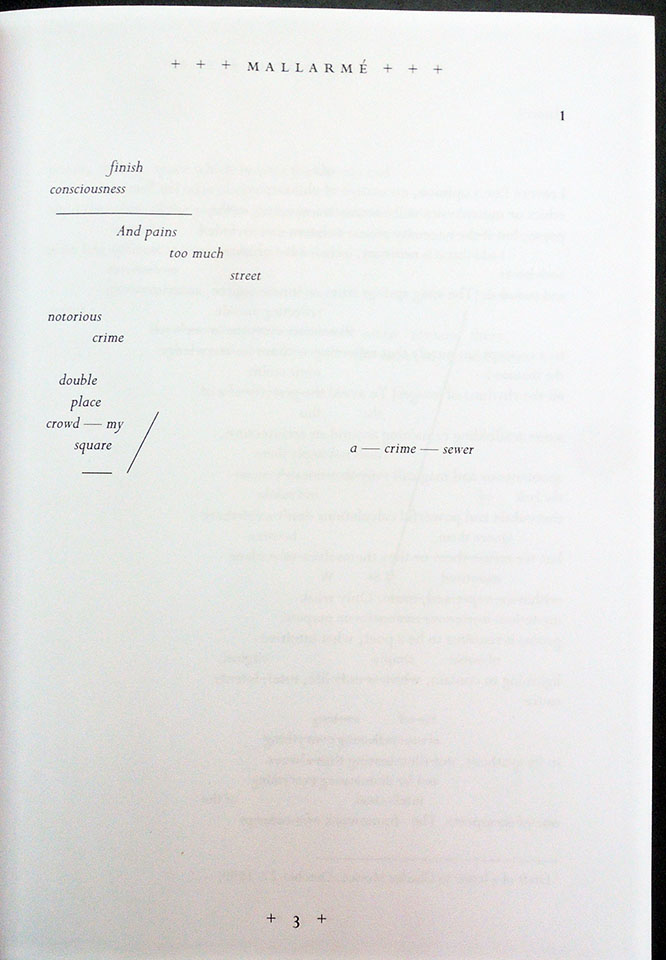

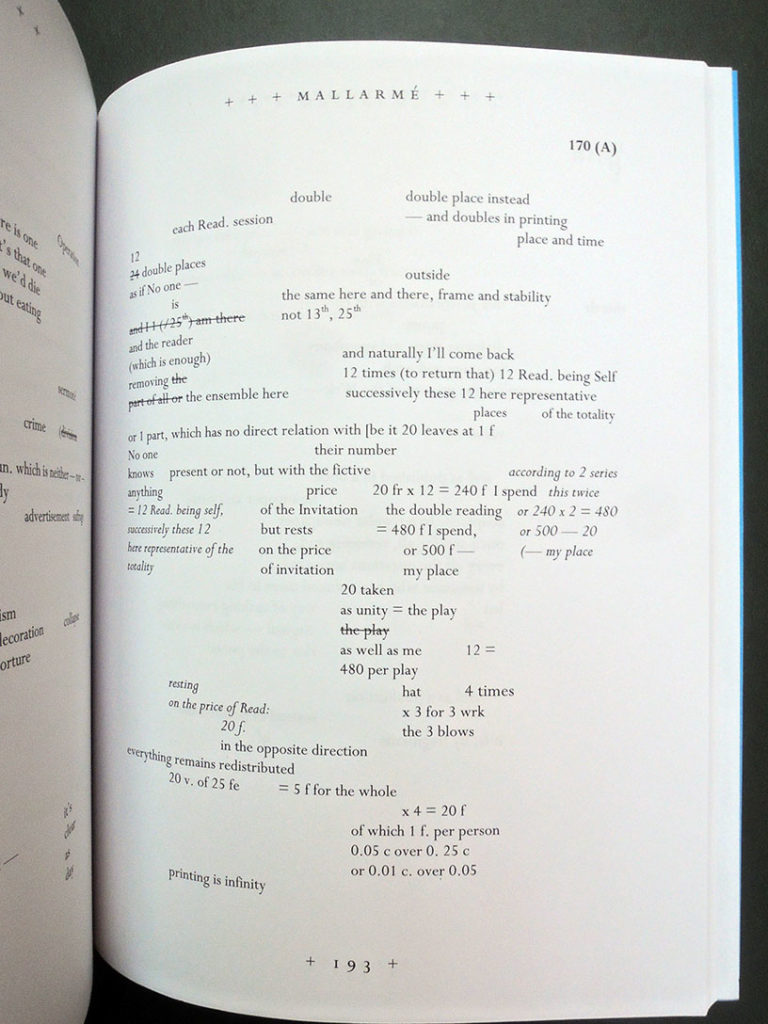

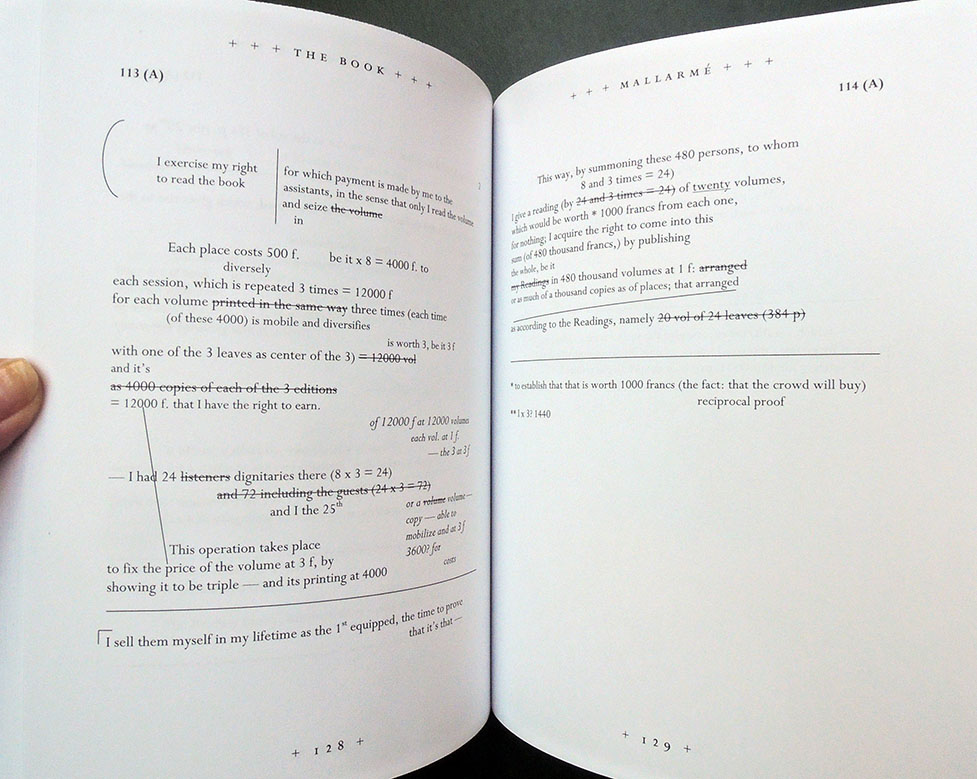

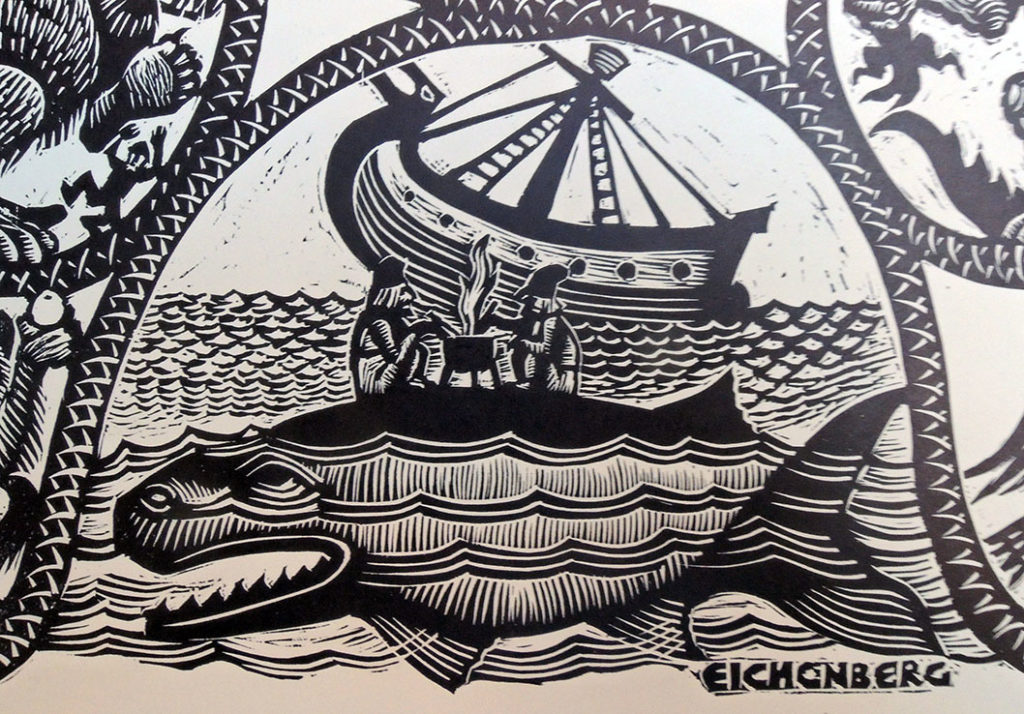

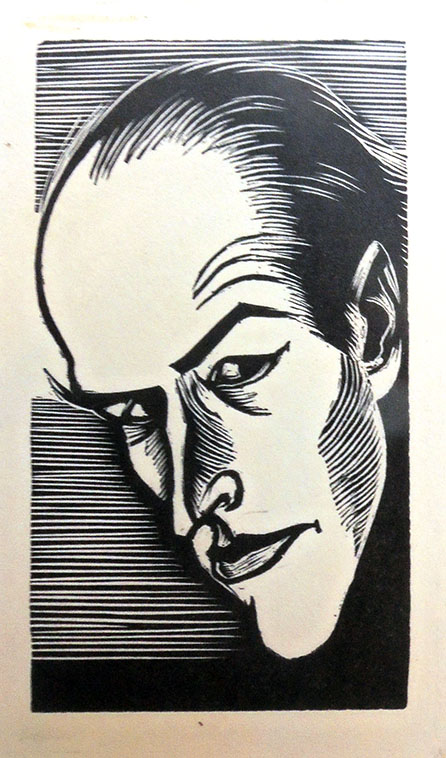

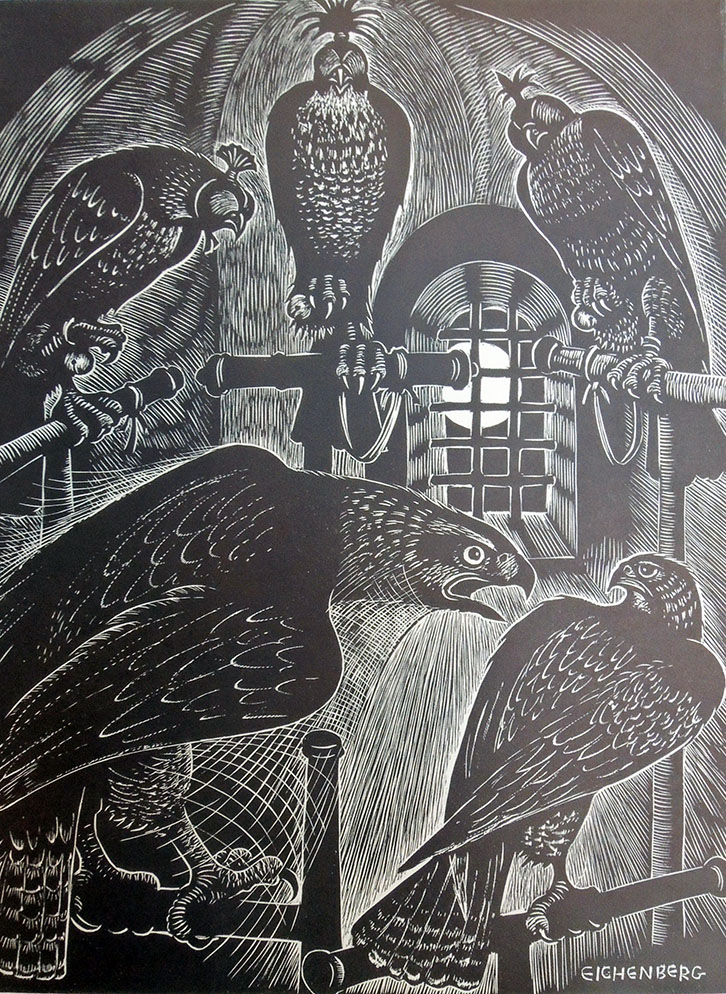

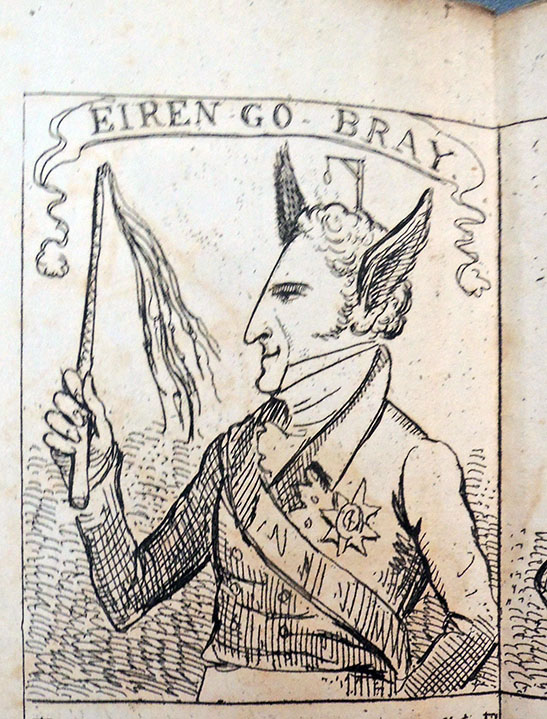

Werner Pfeiffer, State of the Union: a Snapshot of Our Political and Social Conundrum ([Red Hook, N.Y.] : Pear Whistle Press, 2012). Graphic Arts Collection.

Werner Pfeiffer, State of the Union: a Snapshot of Our Political and Social Conundrum ([Red Hook, N.Y.] : Pear Whistle Press, 2012). Graphic Arts Collection.