525 South Avenue, Plainfield, New Jersey, in 2020.

525 South Avenue, Plainfield, New Jersey, in 2020.

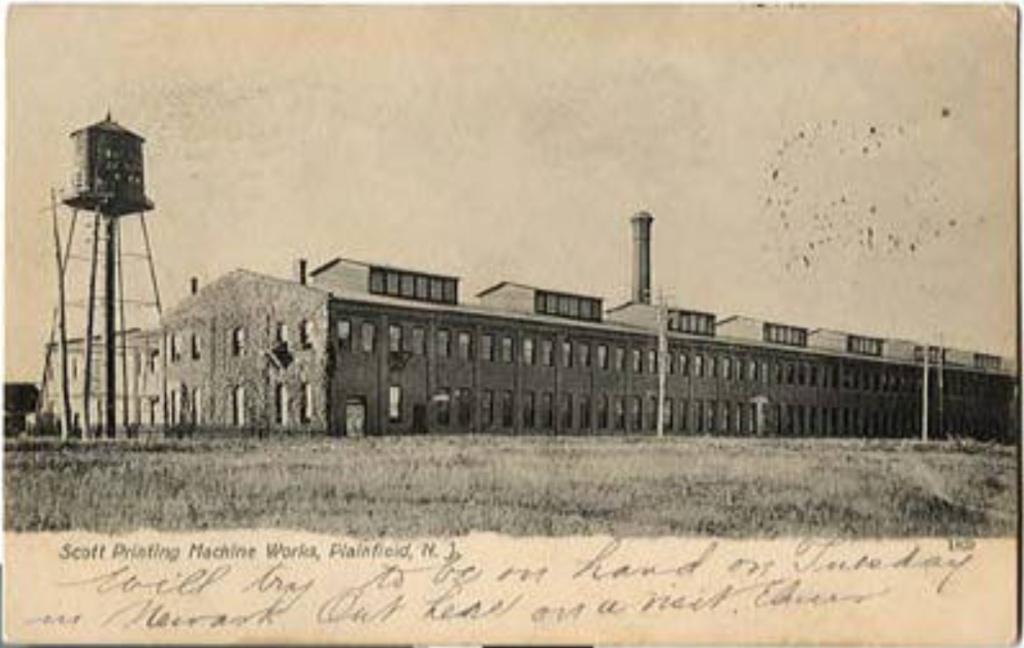

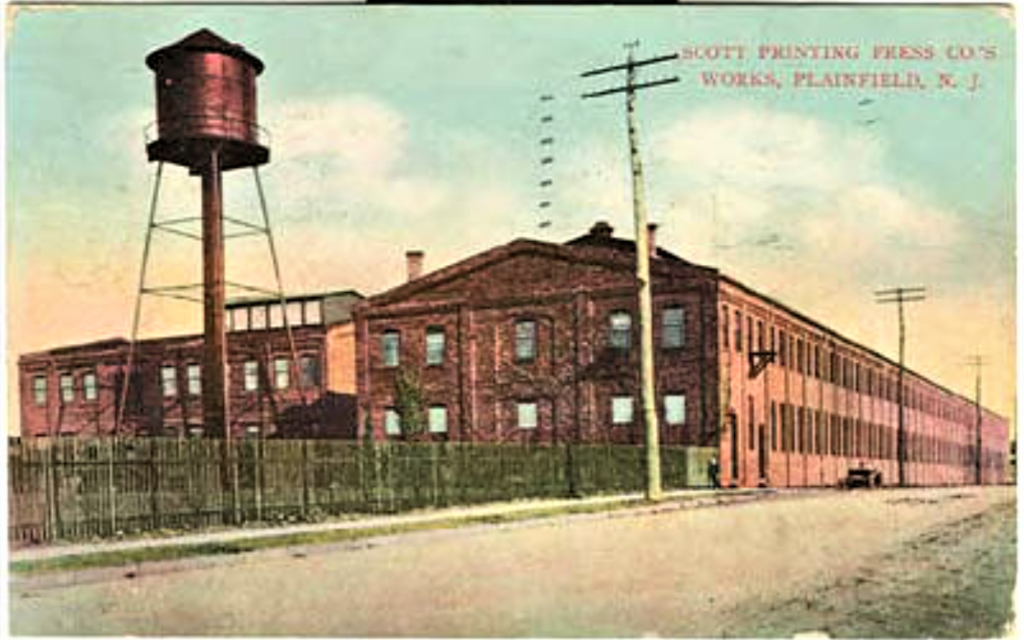

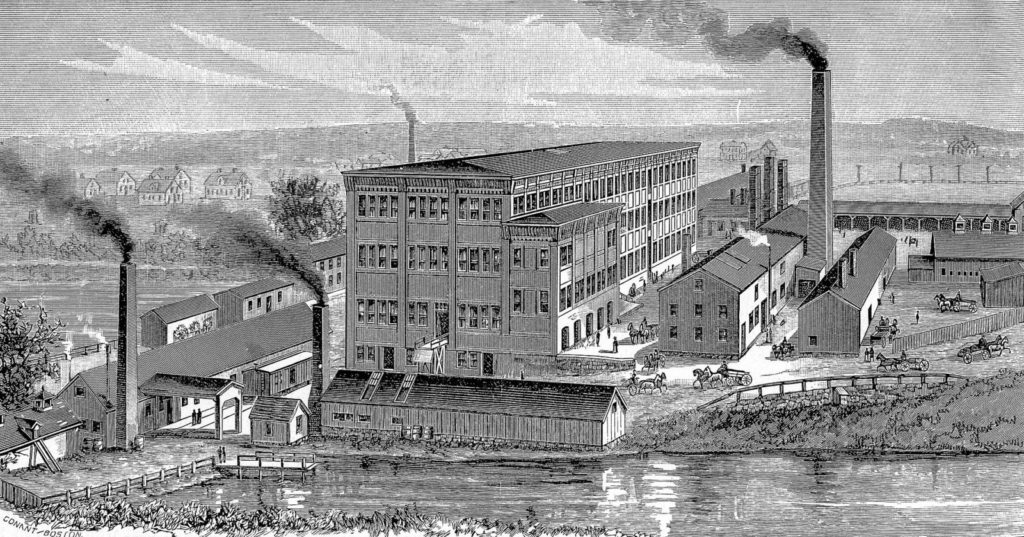

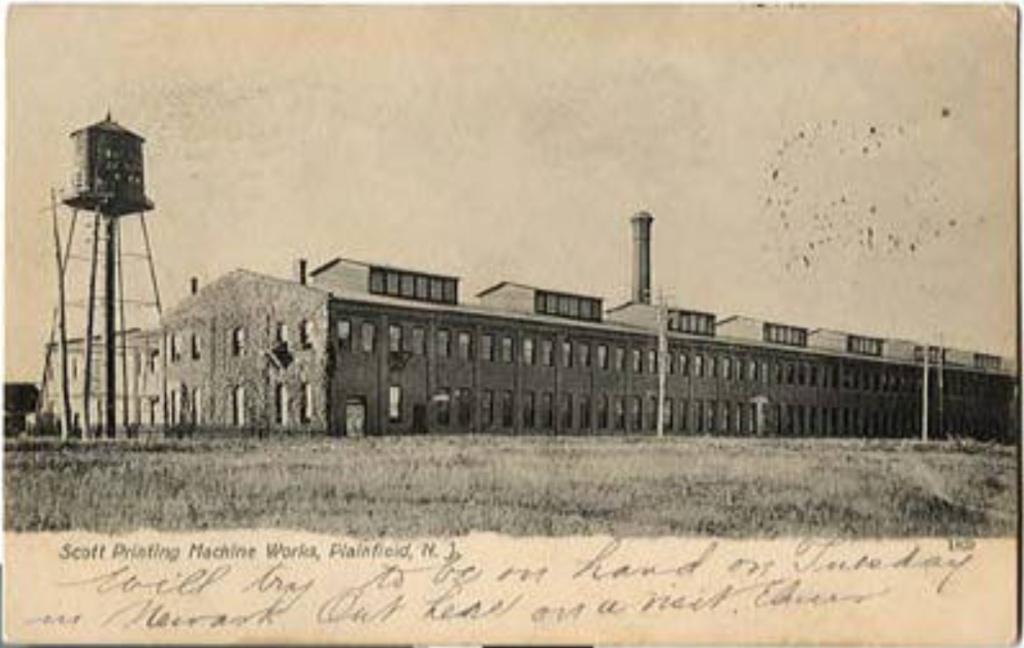

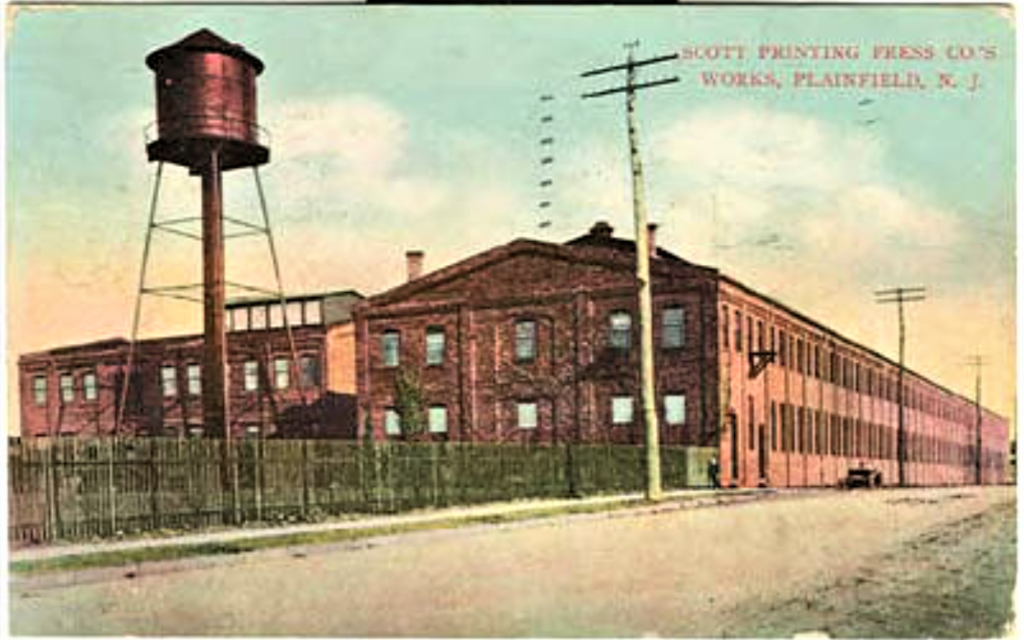

Scott Printing Press Co.’s Works, Plainfield, N.J., Industrial Area, side view of the factory along with the water tank. Plainfield Public Library. https://plainfieldlibrarynj.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p17109coll3

Scott Printing Press Co.’s Works, Plainfield, N.J., Industrial Area, side view of the factory along with the water tank. Plainfield Public Library. https://plainfieldlibrarynj.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p17109coll3

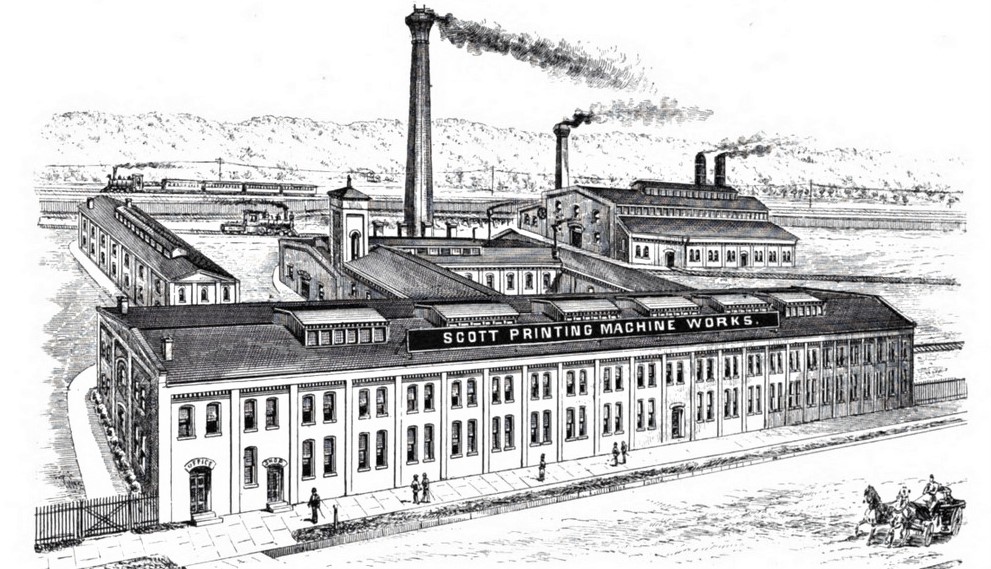

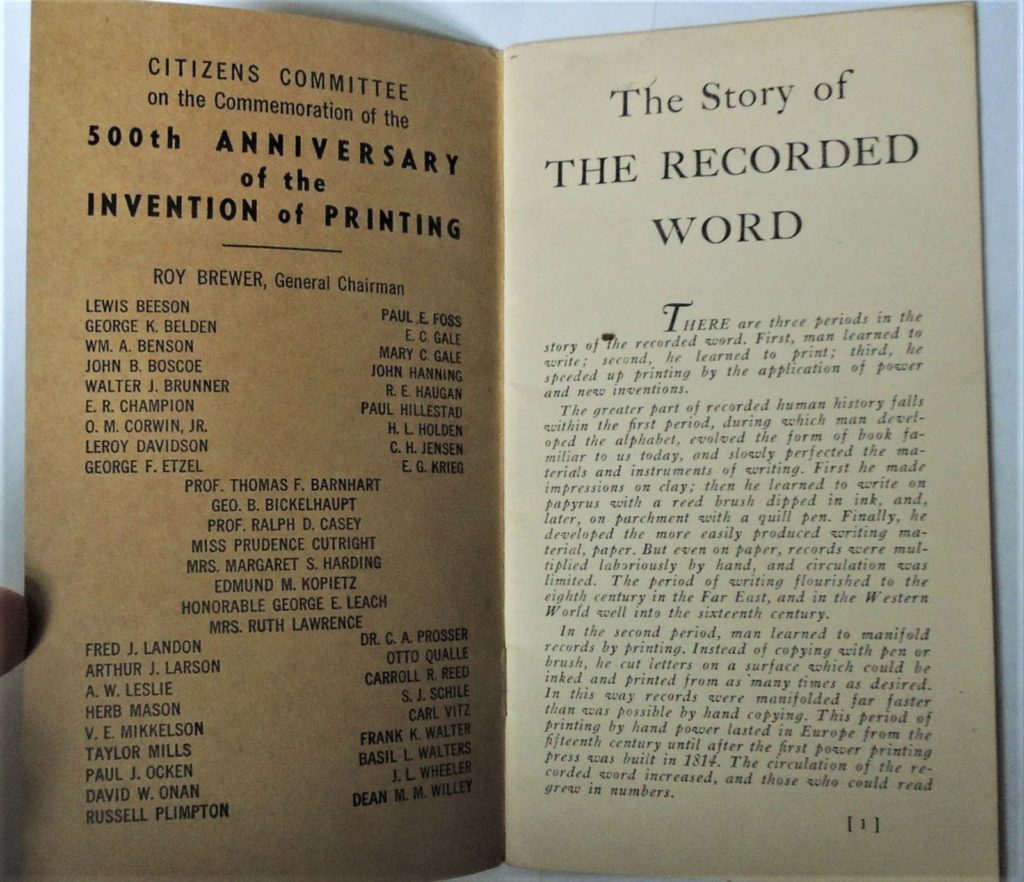

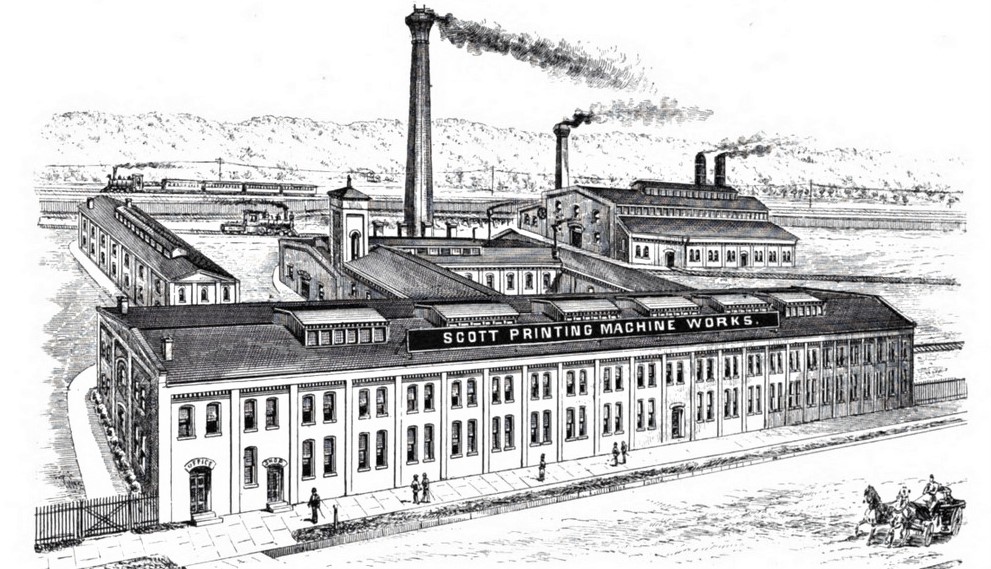

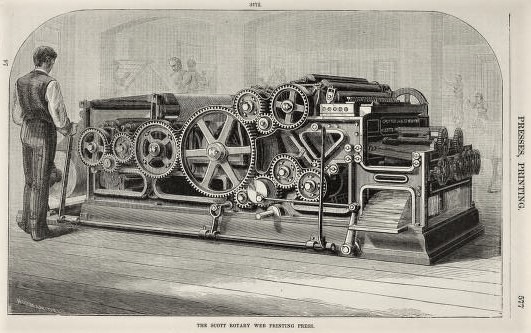

In 1884, Walter Scott (1844-1907) moved his printing press manufacturing business from Chicago to Plainfield, New Jersey, taking over the lot previously used by New Jersey’s Central Baseball Club. By 1903, Walter Scott & Company covered five acres of downtown Plainfield. “The buildings are of brick, contain a floor space of upwards of 115,000 square feet and are connected with each other by a narrow-gauge railroad, 2,300 feet in length, which runs through the buildings.” —Newspaperdom 10 (January 1, 1903).

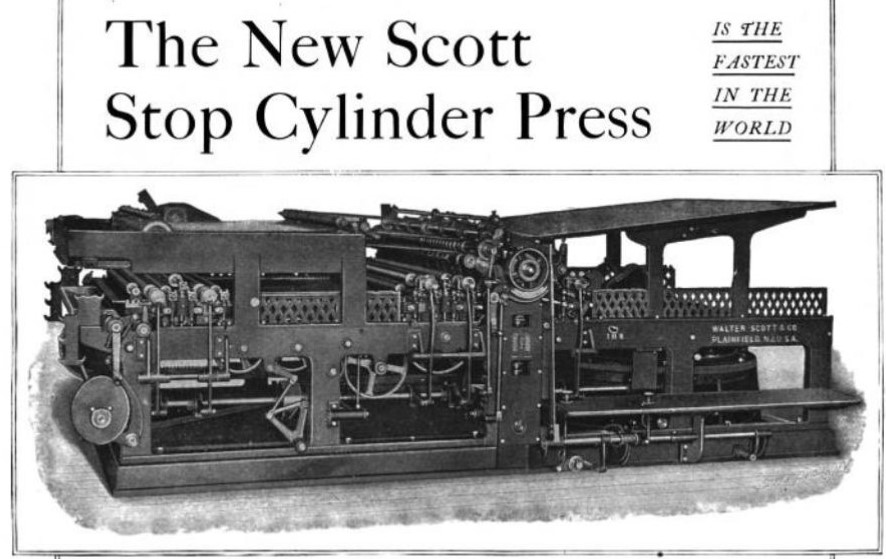

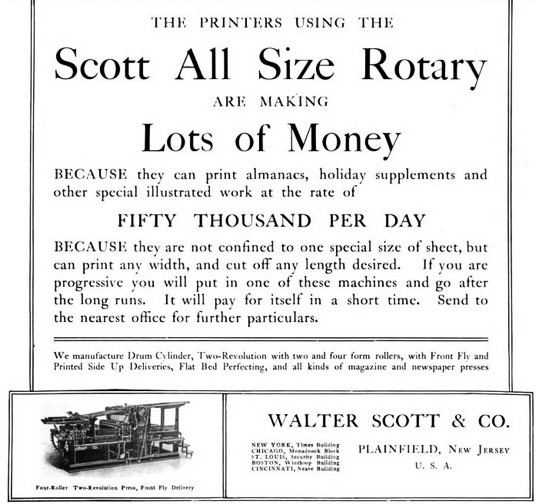

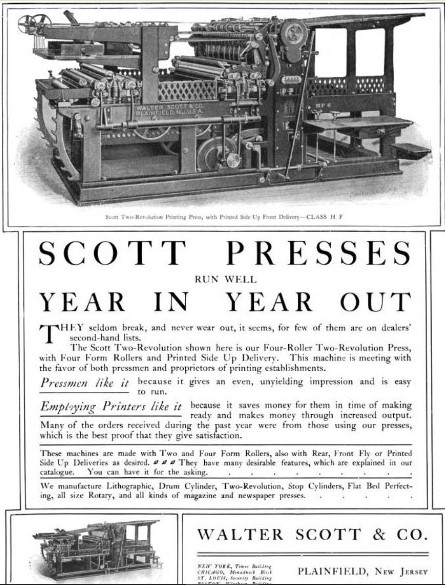

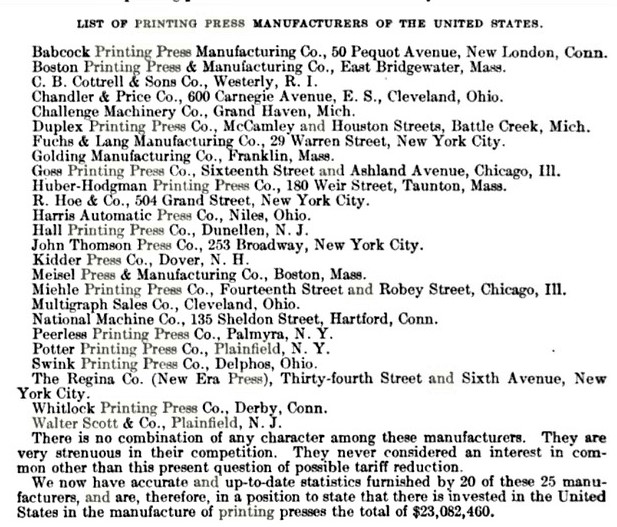

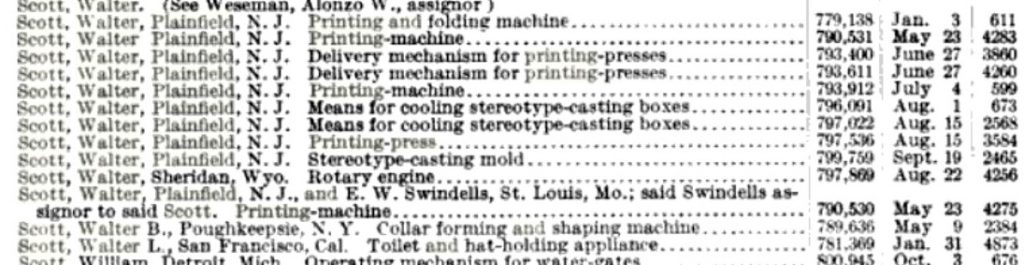

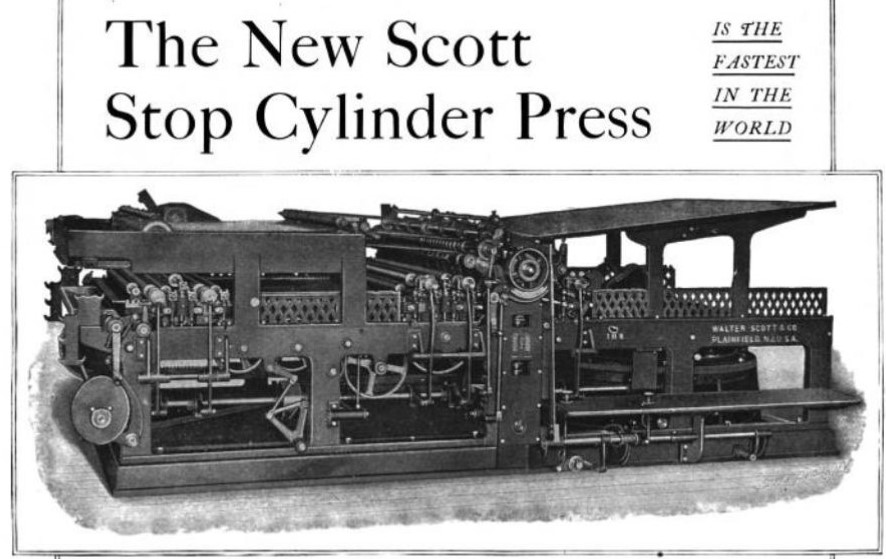

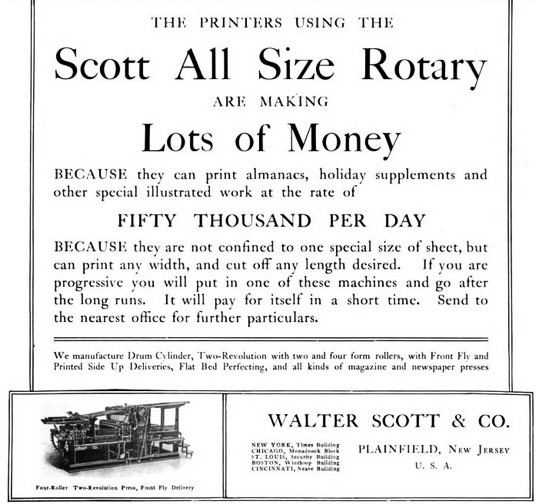

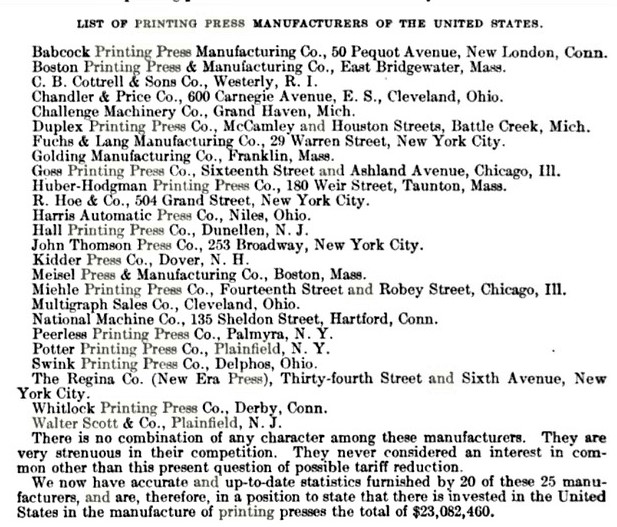

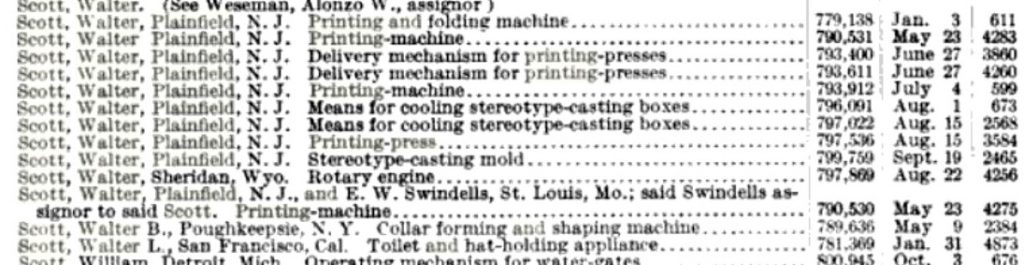

Scott operated the largest printing press manufacturing firm in the United States (claimed to be the largest in the world), known especially for high-speed presses and folding machines used by newspapers. In 1893, the New York World installed the first color press in America adapted to newspaper printing, which was built by Scott’s Company in Plainfield. Known as a brilliant inventor, he received his first patent in 1874 and by 1903, held 200 patents. When he died 1907, his widow, Isabella Scott, operated the business until her death in 1931.

Google maps overview of the factory buildings still standing in 2020. The New Jersey Transit Raritan line still runs along the rear of the buildings.

Google maps overview of the factory buildings still standing in 2020. The New Jersey Transit Raritan line still runs along the rear of the buildings.

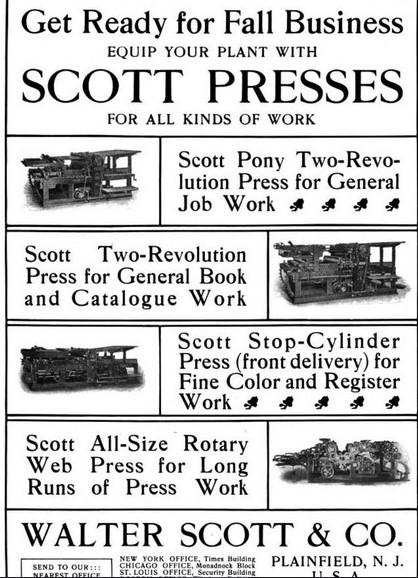

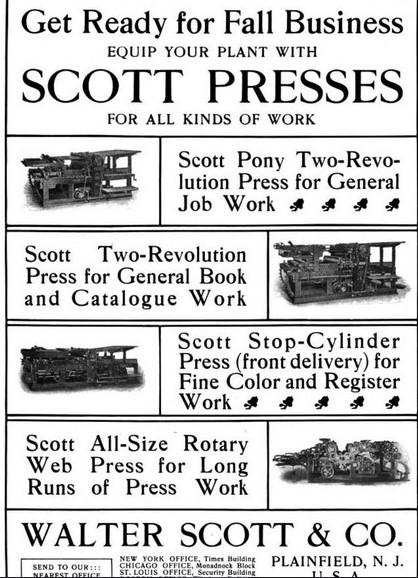

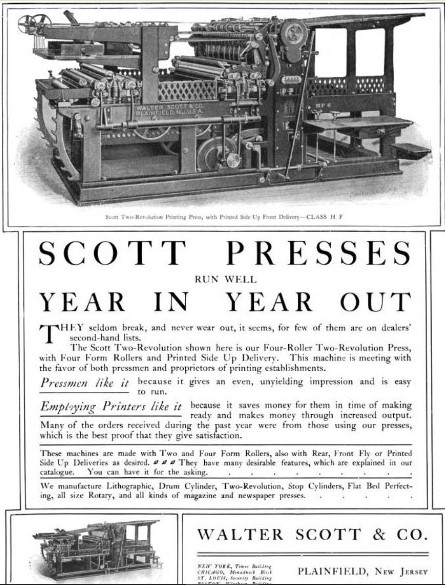

Advertisements: The Inland printer. v.3 (1885/86) and American Printer and Lithographer 31 (1900).

Advertisements: The Inland printer. v.3 (1885/86) and American Printer and Lithographer 31 (1900).

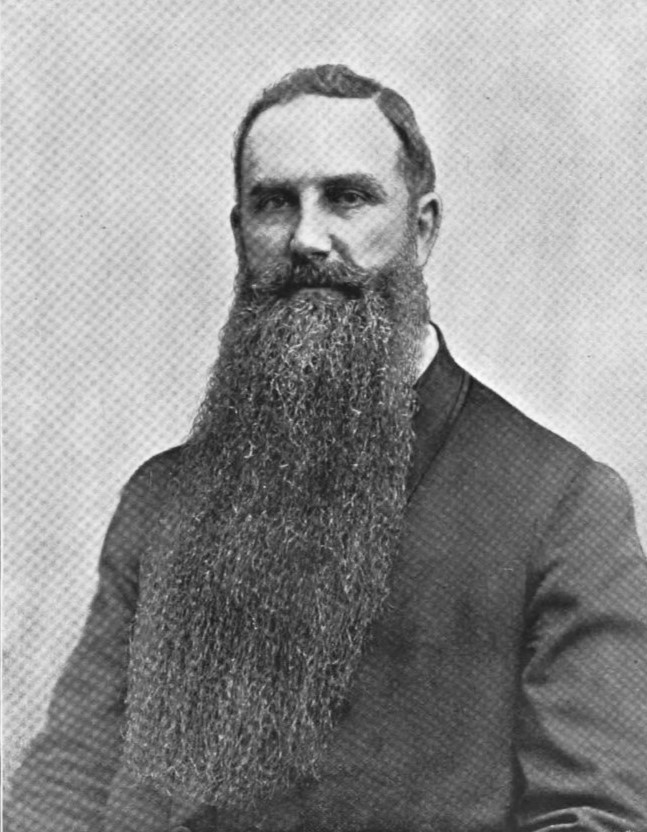

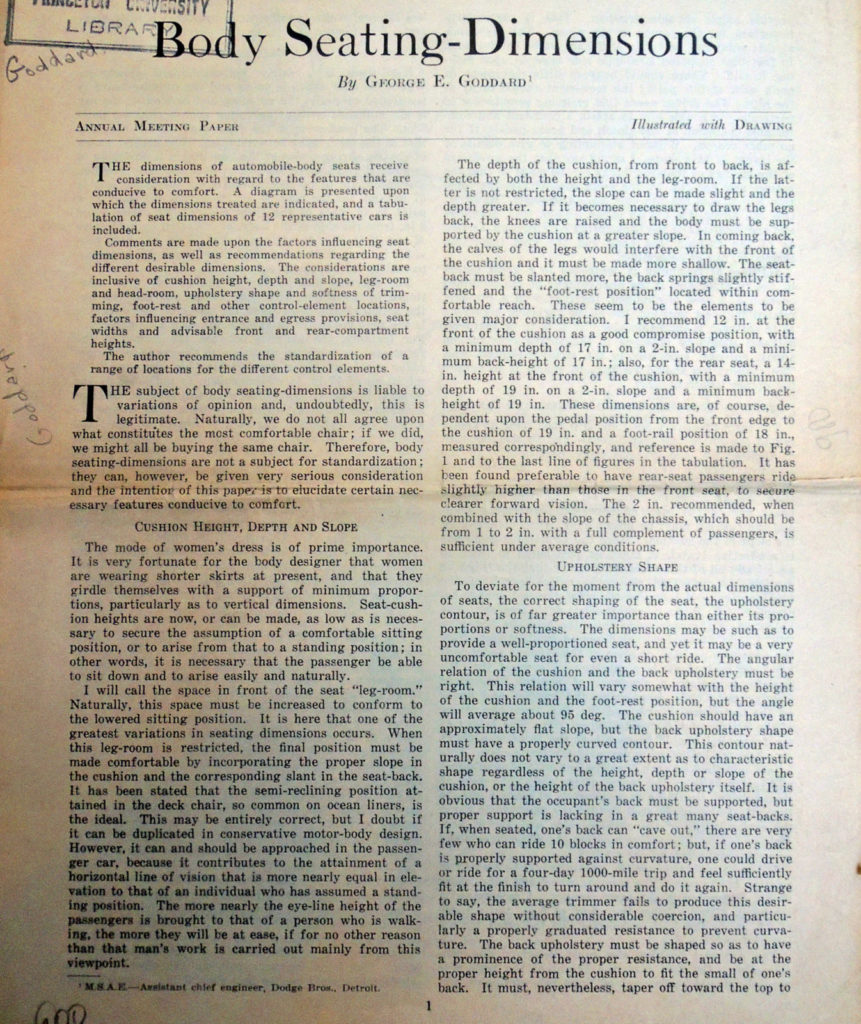

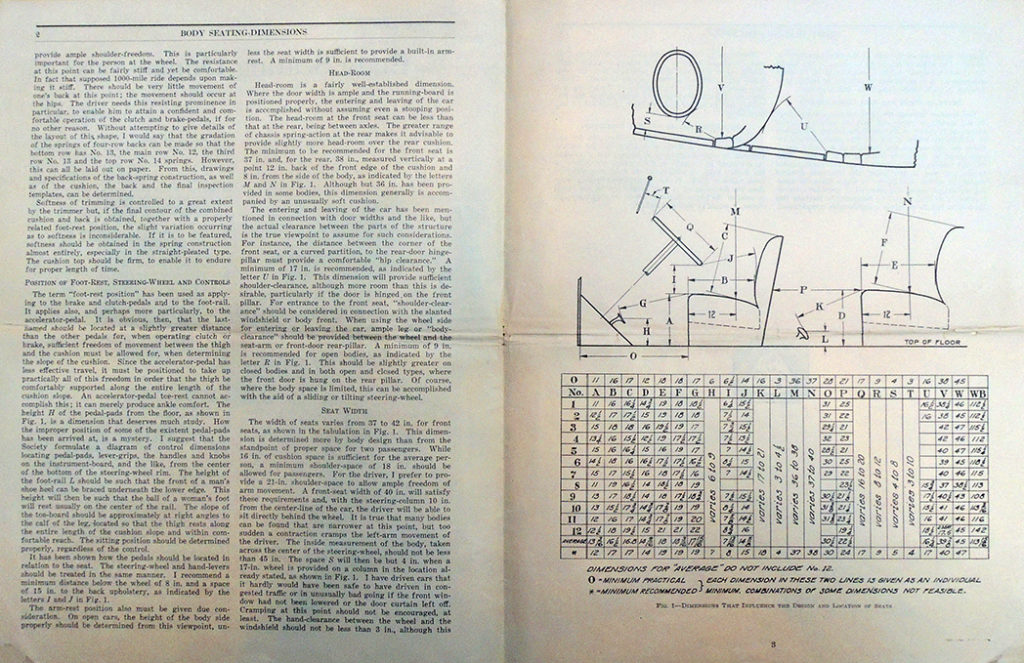

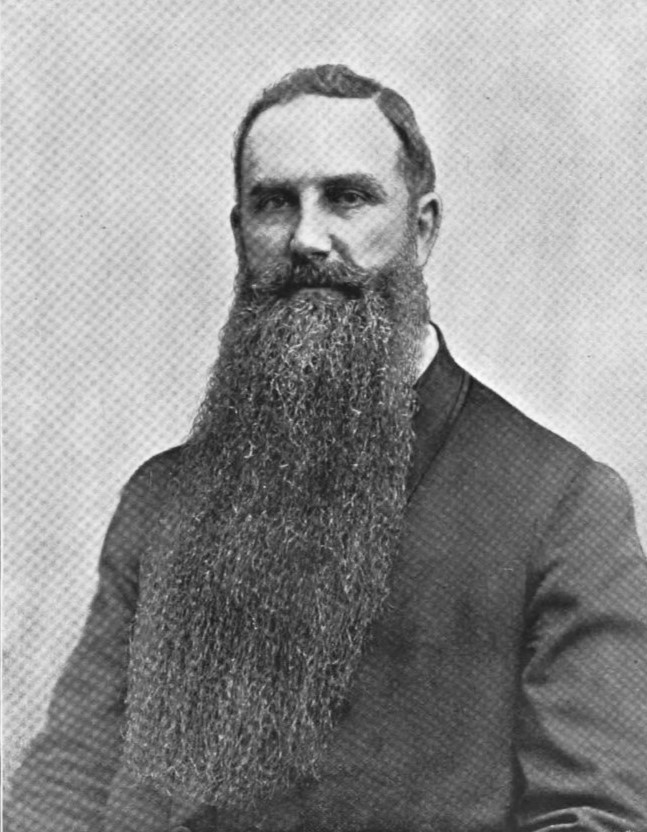

A biographical sketch of Scott was published in The Inland Printer that begins “It is with pleasure that we are enabled to place before our readers the portrait of a gentleman whose name is familiar to every printer in the United States, Mr. Walter Scott. Blessed with great genius, tireless energy, indomitable perseverance, and administrative ability, he has succeeded in building up what is now the largest and most progressive printing press manufacturing establishment in the world.” It continues:

A biographical sketch of Scott was published in The Inland Printer that begins “It is with pleasure that we are enabled to place before our readers the portrait of a gentleman whose name is familiar to every printer in the United States, Mr. Walter Scott. Blessed with great genius, tireless energy, indomitable perseverance, and administrative ability, he has succeeded in building up what is now the largest and most progressive printing press manufacturing establishment in the world.” It continues:

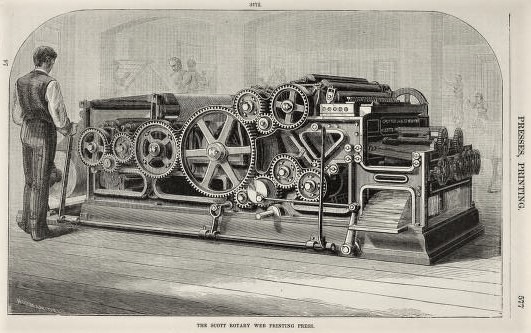

“Mr. Scott was born in Scotland on May 22, 1844. He was educated at the Ayr Academy, studied theoretical and applied mechanics, and learned the machinist trade. He came to the United States in 1869 and settled in Chicago. He was employed in several printing offices, and was for many years foreman of the pressrooms of the Inter Ocean. In 1872 he commenced to make inventions in printing machinery. His mechanical skill and thorough knowledge of the requirements of the printing office enabled him to produce economical and labor-saving machinery which was eagerly sought after by the appreciative printer. Among his inventions at that time was the printing from a web, pasting, cutting and folding, so as to produce a newspaper with the leaves cut in book from at one operation; also a new rotary web printing and folding machine which produced 30,000 copies per hour.

The demand for Mr. Scott’s improved machines became so great … that in 1884 it was found necessary to erect extensive and commodious works at Plainfield, New Jersey, a cut and description of which will be found below. Messrs. Walter Scott & Co. now makes no less than 117 different kinds and sizes of printing machines, ranging from a small cylinder press to a large book and newspaper machine costing $40,000 and capable of printing, pasting, cutting, and folding 96,000 eight-page papers per hour; besides many other machine and appliances connected with printing.

…This extensive manufactory is situated on South Avenue, between Richmond and Berckman Streets, and adjacent to the central Railroad of New Jersey, in the city of Plainfield. The works occupy five acres, are connected with the central Railroad by a siding and 1,700 feet of rails are laid through the yard to the various building. … The area of floor space is over 78,000 square feet. The buildings are beautifully lighted up by 25 arc and 400 incandescent electric lights, the dynamos of which are placed in the engine room.

…The factory and its equipment are the most complete of anything we have ever seen in this line of manufacture, and we understand it is the largest exclusively devoted to the manufacture of printing and kindred machinery in the United States, over one hundred and fifty machines being in process of construction at one time.– The Inland Printer, American Lithographer 7 (1889/1890): 564-66

See also:

Frederick W. Hamilton, Type and presses in America, a brief historical sketch of the development of type casting and press building in the United States ([Chicago] Pub. by the Committee on education, United typothetae of America, 1918). Graphic Arts Collection 2006-1856N

Herbert L. Baker, Cylinder printing machines, being a study of the mechanism and operation of the principal types of cylinder printing machines ([Chicago] Pub. by the Committee on education, United typothetae of America, 1918). Graphic Arts Collection 2007-0021N

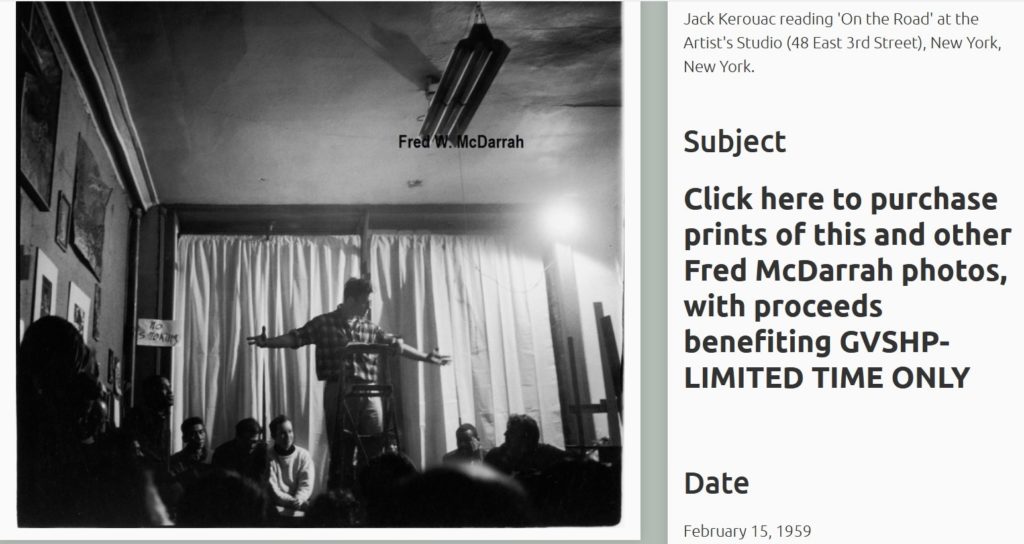

There is an archive to their newsletters, with information on the preservation of individual buildings as well as neighborhoods: https://www.villagepreservation.org/about-us/newsletter/

There is an archive to their newsletters, with information on the preservation of individual buildings as well as neighborhoods: https://www.villagepreservation.org/about-us/newsletter/

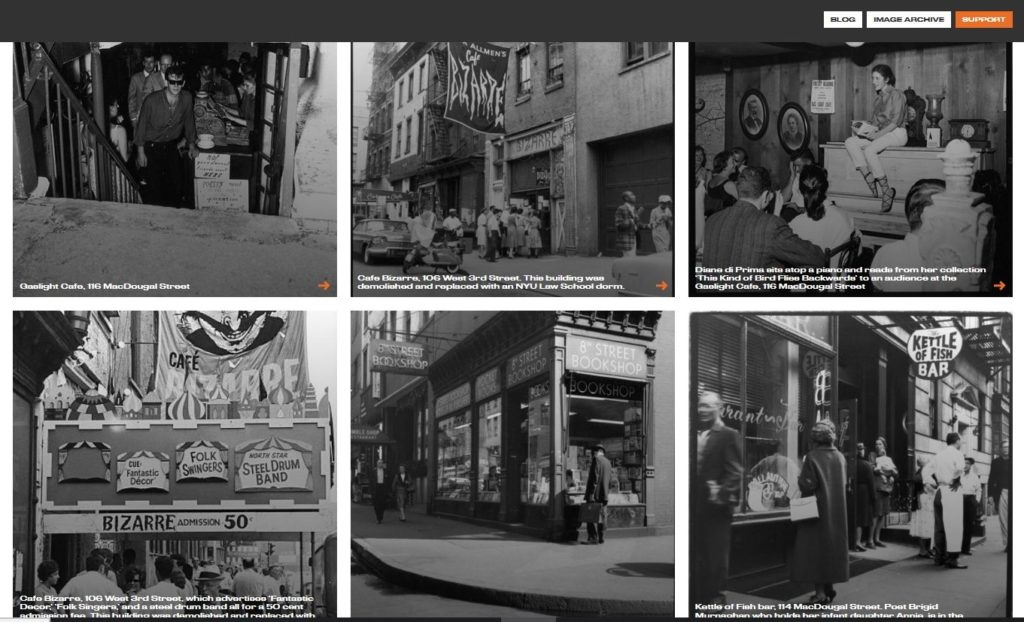

All walking tours are currently virtual but will hit the streets again as soon as it is safe.

All walking tours are currently virtual but will hit the streets again as soon as it is safe.