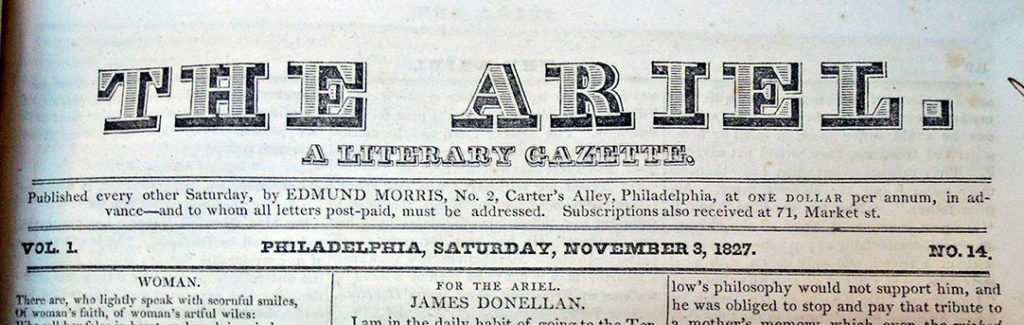

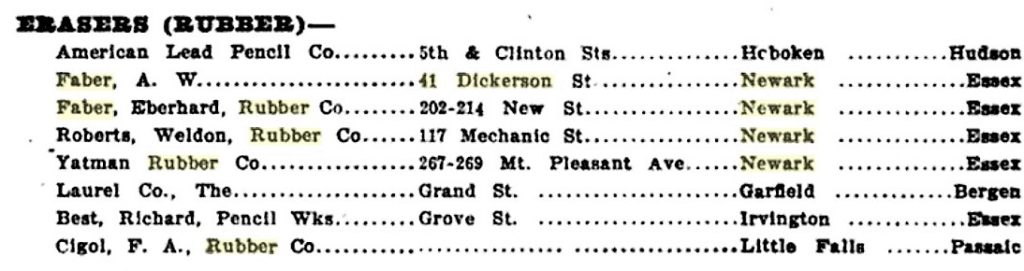

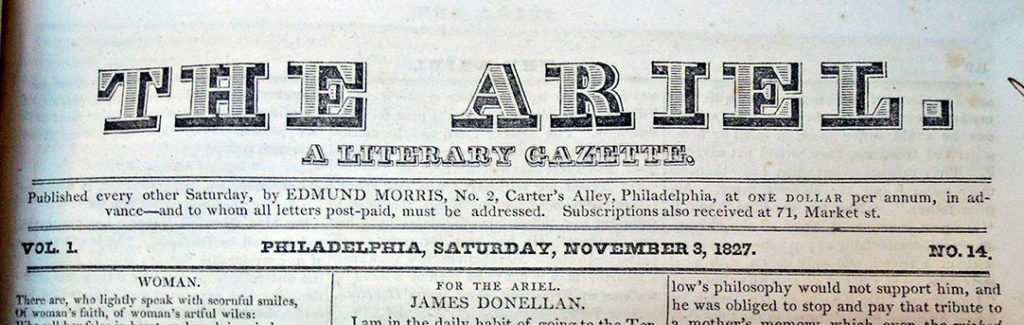

Sections from the ode “To A, B, C, & Co.” have been reprinted many times in many sources over the years. A search for the original publication of the poem led to the November 9, 1827 issue of The Ariel, a Philadelphia literary gazette.

Sections from the ode “To A, B, C, & Co.” have been reprinted many times in many sources over the years. A search for the original publication of the poem led to the November 9, 1827 issue of The Ariel, a Philadelphia literary gazette.

Although no author is given, the work was written by the New Jersey poet Samuel Joseph Smith (1771-1835), who lived as somewhat of a recluse outside Burlington, rarely leaving the family home. The biography by his cousin Amelia Smith that accompanies a compilation of his writings claims this verse is autobiographical.

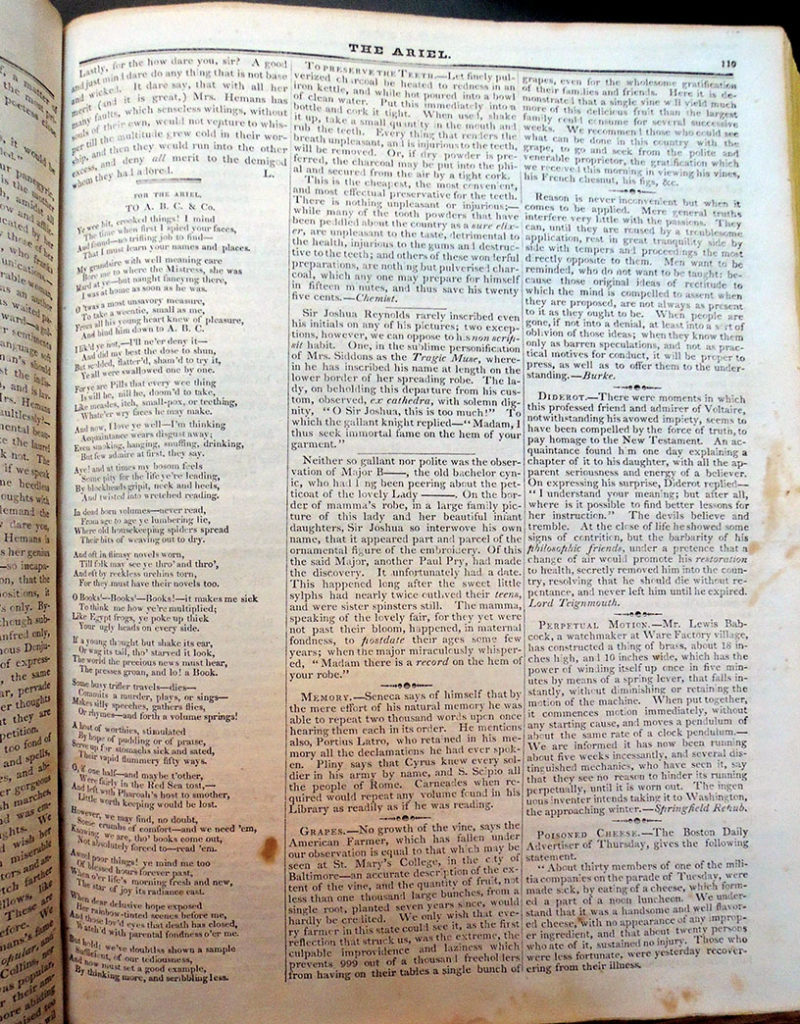

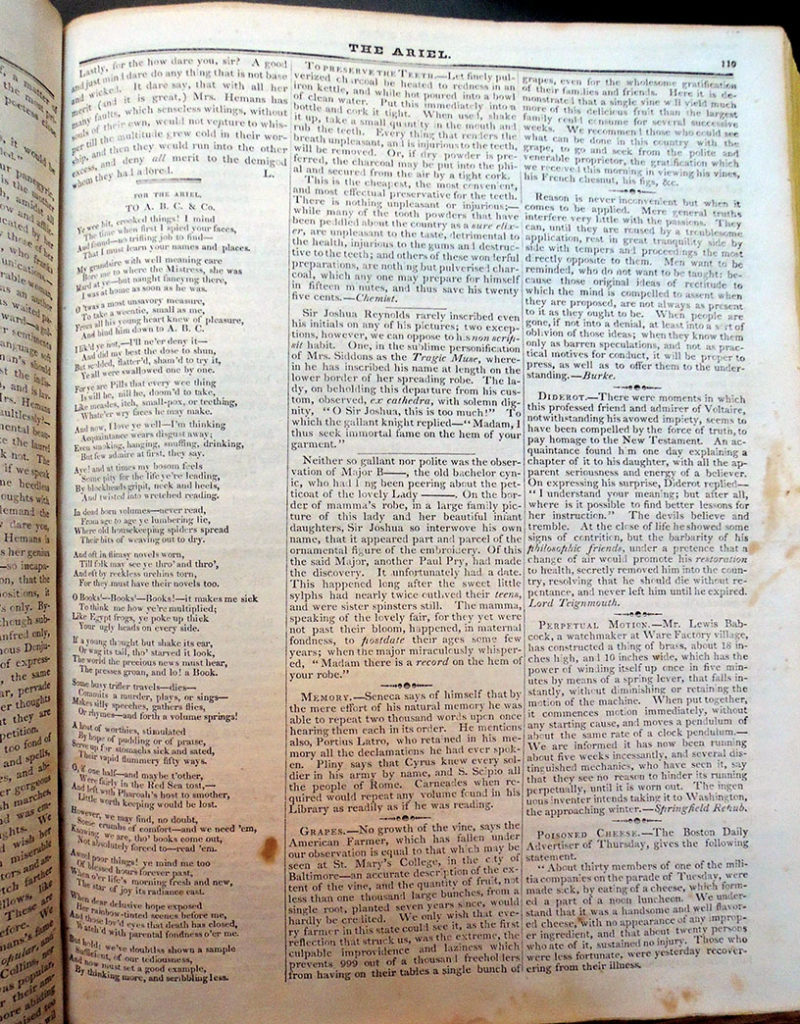

Here’s the whole:

Ye wee bit, crooked things ! I mind

The time when first I spied your faces,

And found—no trifling job to find—

That I must learn your names and places.

My grandsire, with well-meaning care,

Bore me to where the mistress she was

Hard at ye—but naught fancying there,

I was at home as soon as he was.

O ‘t was a most unsavoury measure,

To take a weentie, small as me,

From all his young heart knew of pleasure,

And bind him down to A, B, C.

I liked ye not—I’ll ne’er deny it—

And did my best the dose to shun,

But scolded, flattered, shamed, to try it,

Ye all were swallowed, one by one.

For ye are pills that every wee thing,

Is, will he, nill he, doomed to take,

Like measles, itch, small-pox, or teething,

Whate’er wry faces he may make.

And now I love ye well, I’m thinking,

Acquaintance wears disgust away;

Even smoking, hanging, snuffing, drinking,

But few admire at first, they say.

Aye ! and at times my bosom feels

Some pity for the life ye ‘re leading,

By blockheads gripit, neck and heels,

And twisted into wretched reading.

In dead born volumes—never read—

From age to age ye lumbering lie,

Where old housekeeping spiders spread

Their bits of weaving out to dry.

And oft in flimsy novels worn,

Till folk may see ye through and through,

And oft by reckless urchins torn,

For they must have their novels too.

O books ! books ! books !—it makes me sick

To think me how ye ‘re multiplied;

Like Egypt’s frogs, ye poke up thick

Your ugly heads on every side.

If a young thought but shake its ear,

Or wag its tail, though starved it look,

The world the precious news must hear,

The presses groan, and lo ! a Book.

Some busy trifler travels—dies—

Commits a murder, plays or sings—

Makes silly speeches, gathers flies,

Or rhymes—and forth a volume springs!

A host of worthies, stimulated

By hope of pudding or of praise,

Serve up, for stomachs sick and sated,

Their vapid flummery fifty ways.

O, if one half—and may be t’ other,

Were fairly in the Red Sea tost,

And left with Pharaoh’s host to smother,

Little worth keeping would be lost.

However we may find, no doubt,

Some crumbs of comfort—and we need ’em;

Knowing, we are, though books come out,

Not absolutely forced to read ’em.

Aweel, poor things! ye mind me, too,

Of blessed hours for ever past,

When o’er life’s morning fresh and new,

The star of joy its radiance cast.

When dear delusive hope exposed

Her rainbow-tinted scenes before me,

And those loved eyes that death has closed,

Watched with parental fondness o’er me.

But hold; we’ve doubtless shown a sample,

Sufficient, of our tediousness,

And now must set a good example,

By thinking more, and scribbling less.

Samuel Joseph Smith, Miscellaneous Writings of the Late Samuel J. Smith of Burlington, N.J. (H. Perkins, 1836)

Published in The Ariel: A Literary Gazette, Vol. 1 no. 14 (November 3, 1827)

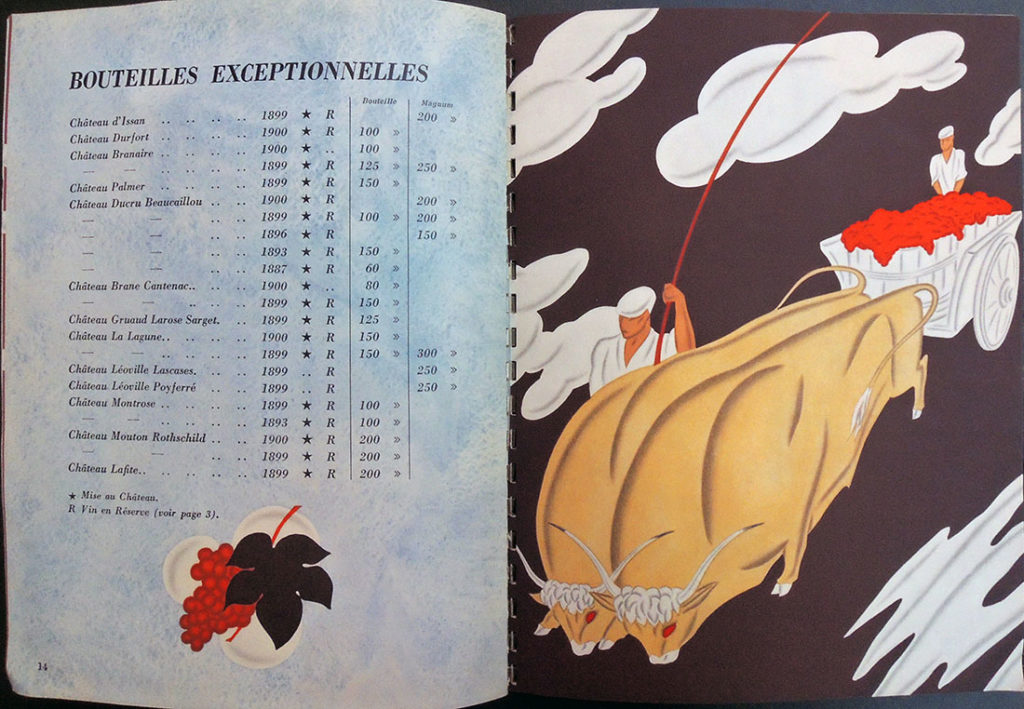

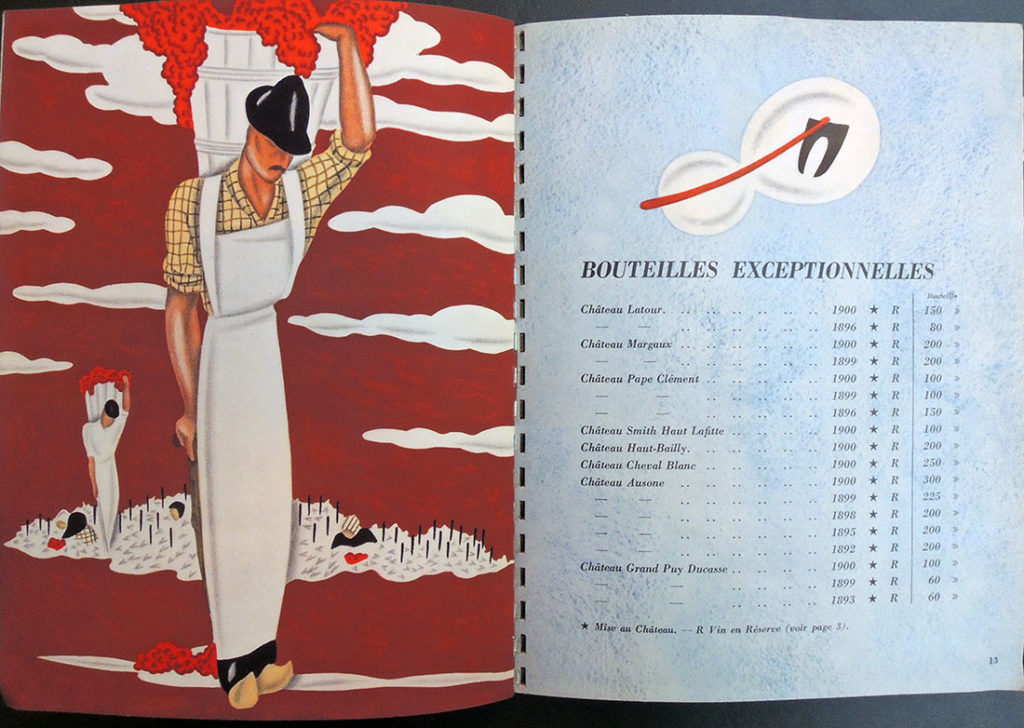

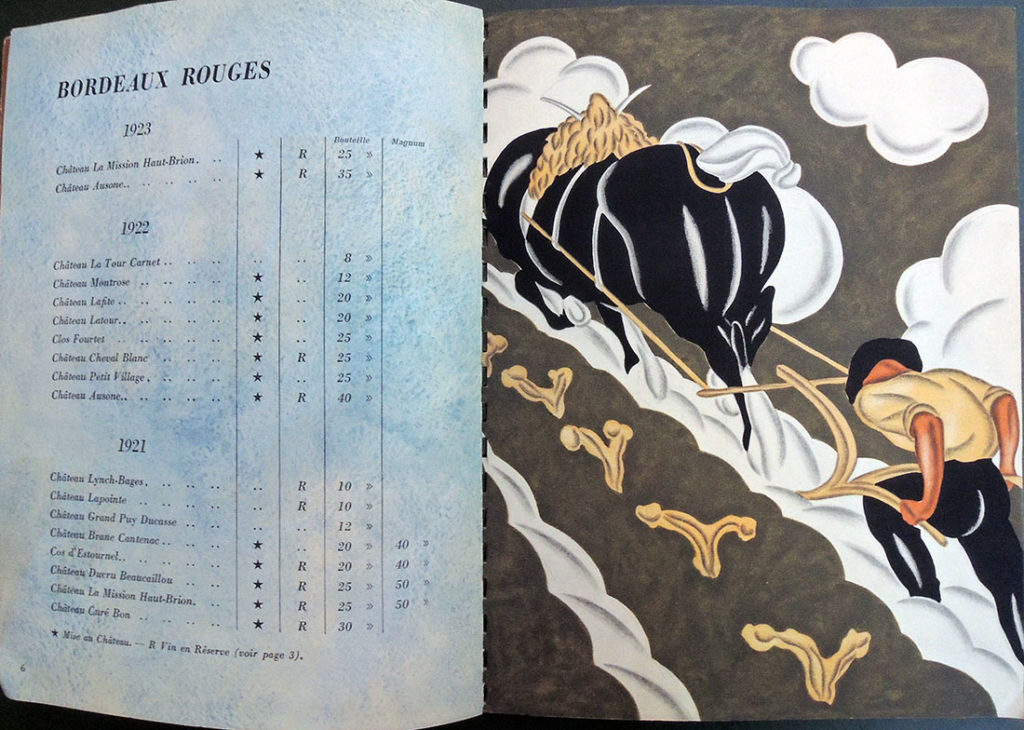

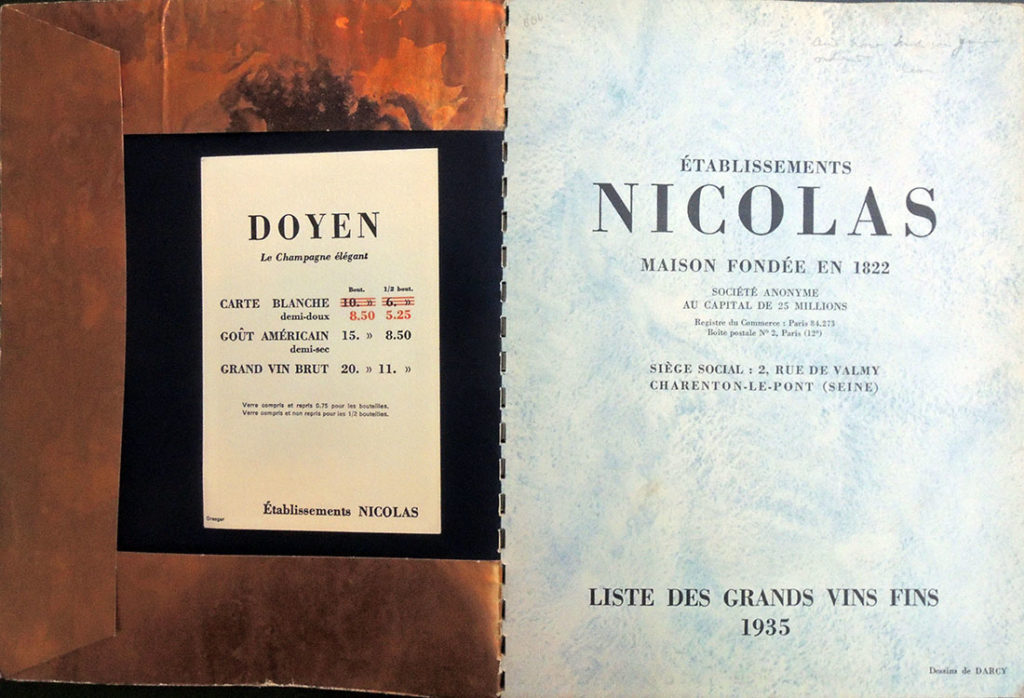

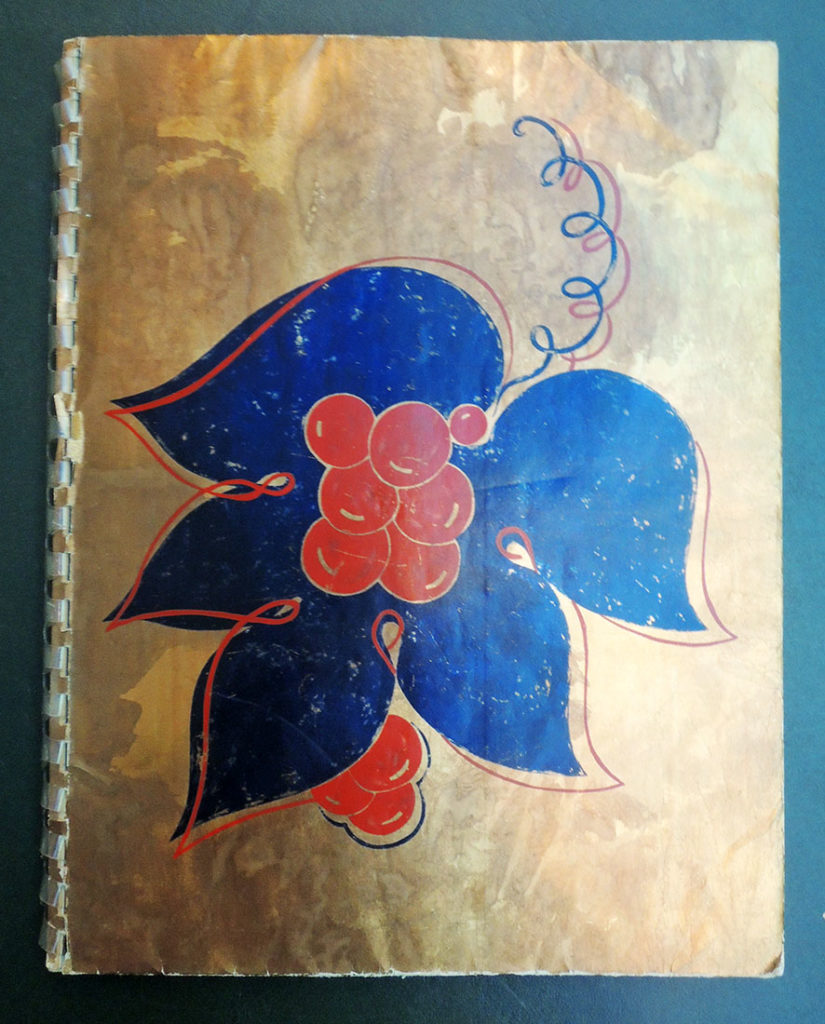

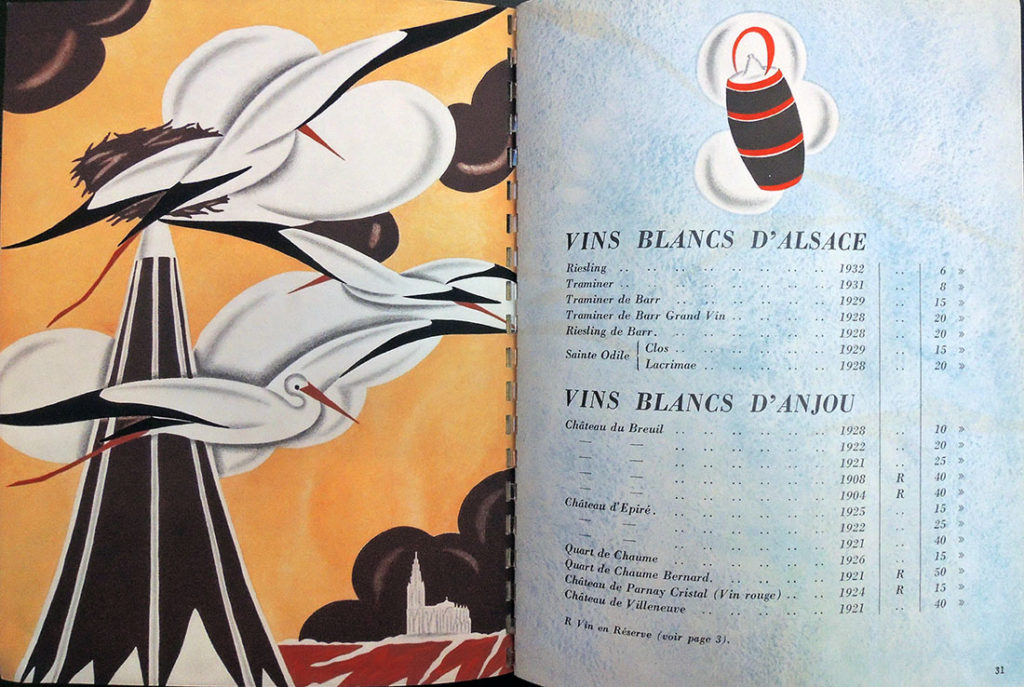

A.M. (Adolphe Mouron) Cassandre (1901-1968), Établissements Nicolas maison fondée en 1822 … liste des grands vins fins (Charenton-le-pont [Paris]: [Établissements Nicolas]; [Paris]: Imp. Draeger, 1930). Ephemera – advertising

A.M. (Adolphe Mouron) Cassandre (1901-1968), Établissements Nicolas maison fondée en 1822 … liste des grands vins fins (Charenton-le-pont [Paris]: [Établissements Nicolas]; [Paris]: Imp. Draeger, 1930). Ephemera – advertising A student of the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, France, Adolphe Mouron Cassandre was a painter, commercial poster artist and typeface designer. His inventive graphic techniques show influences of Surrealism and Cubism and became very popular in Europe and the US during the 1930s.

A student of the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, France, Adolphe Mouron Cassandre was a painter, commercial poster artist and typeface designer. His inventive graphic techniques show influences of Surrealism and Cubism and became very popular in Europe and the US during the 1930s.