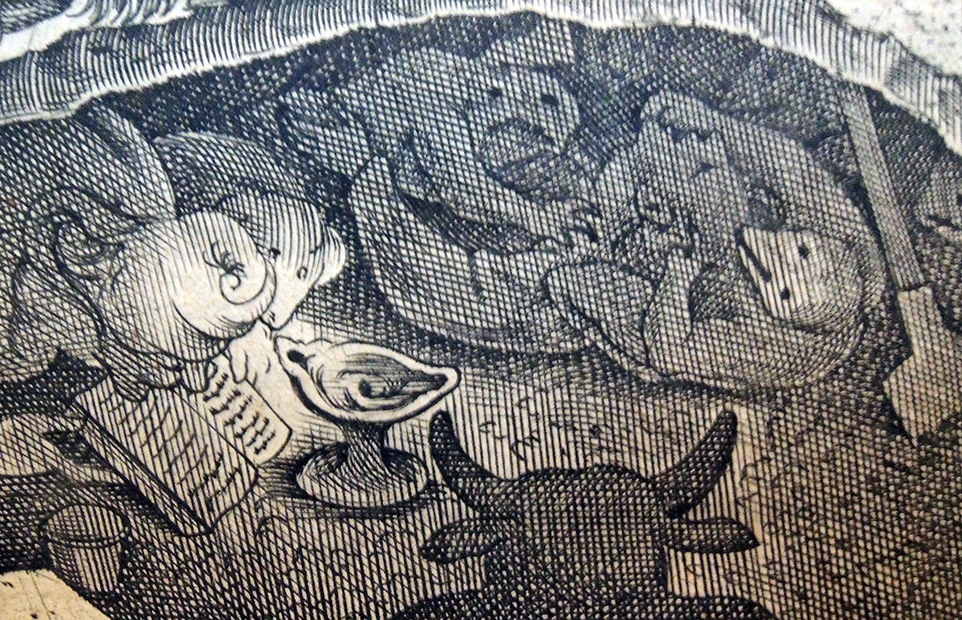

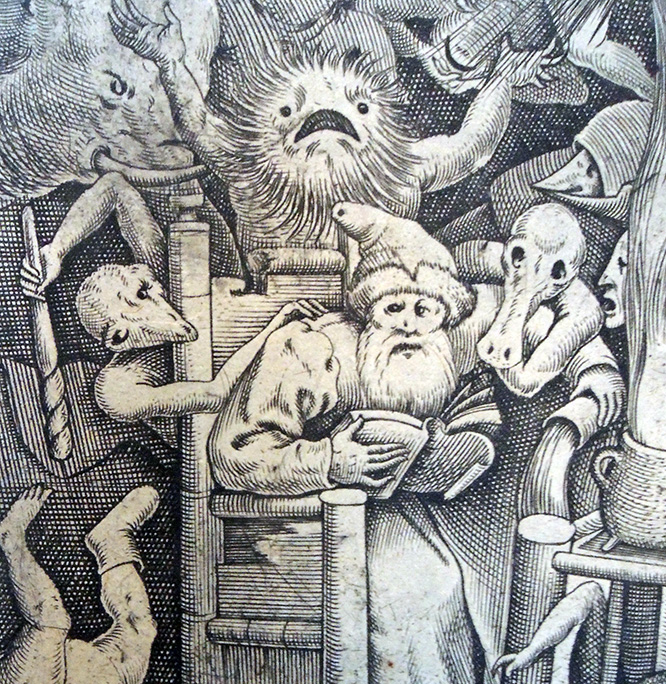

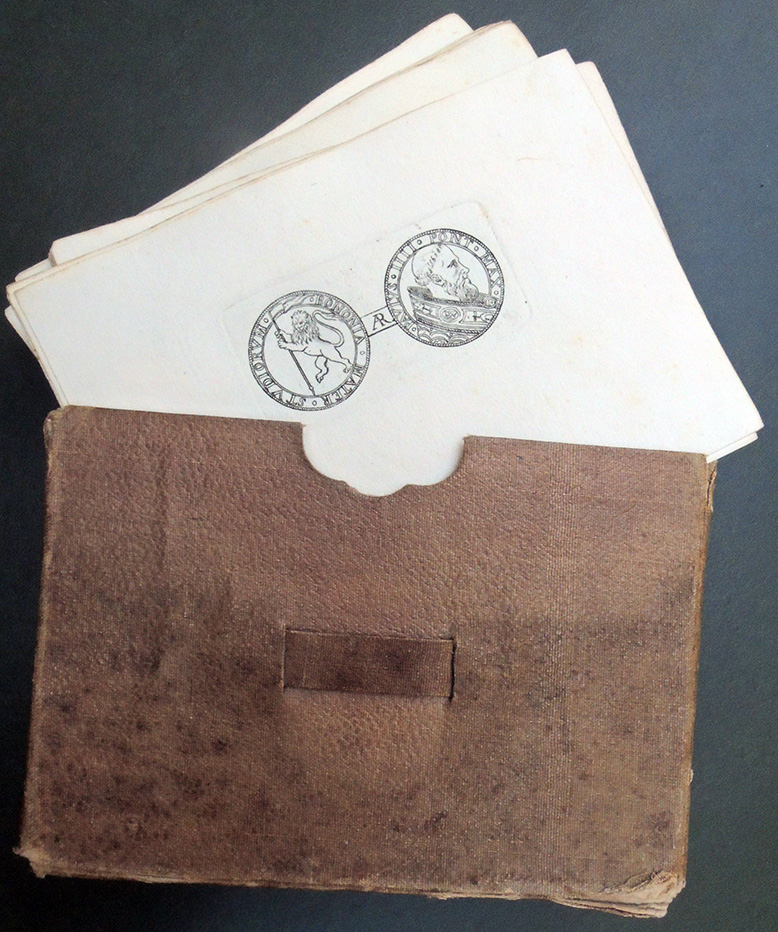

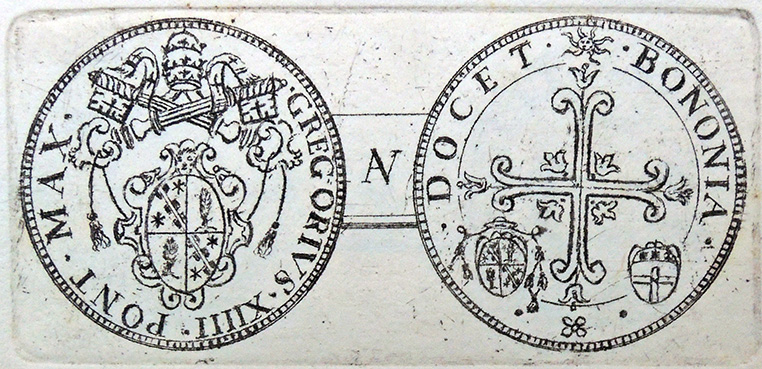

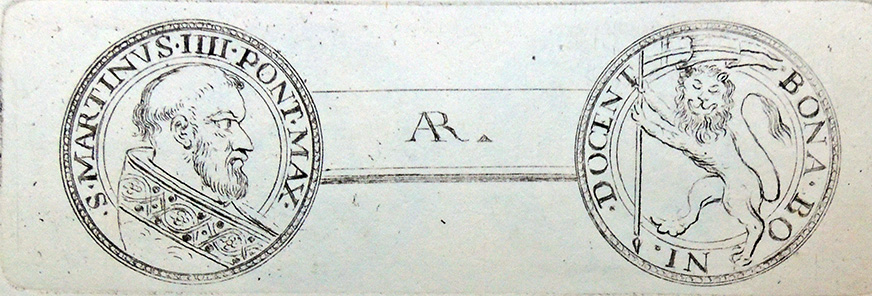

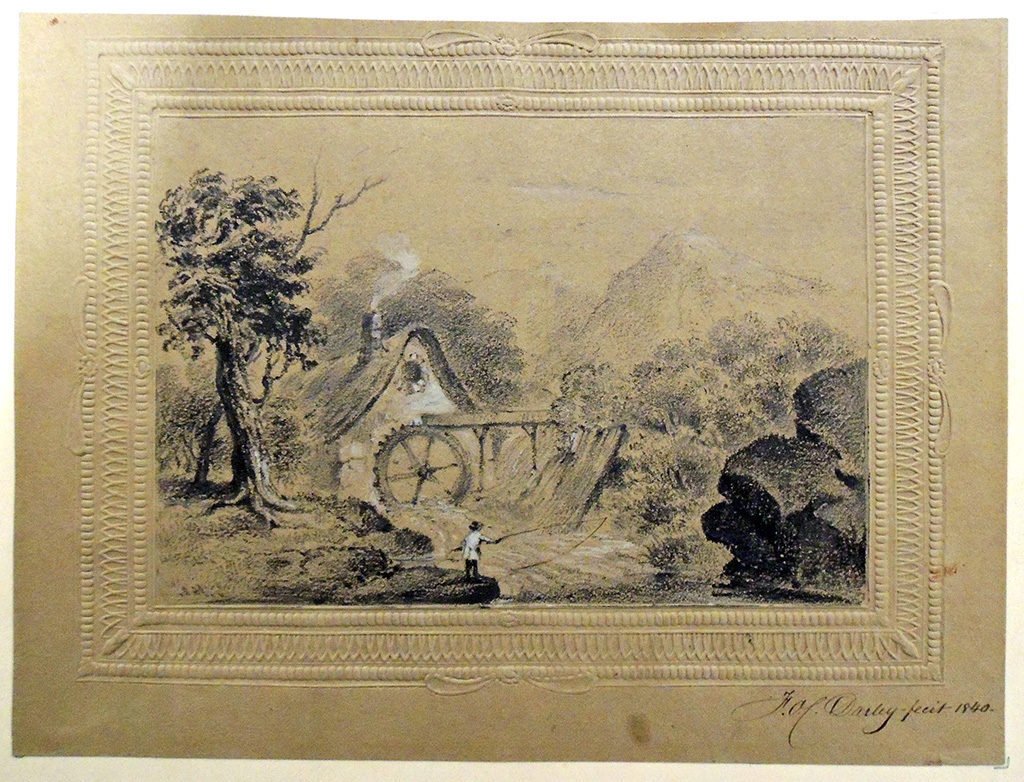

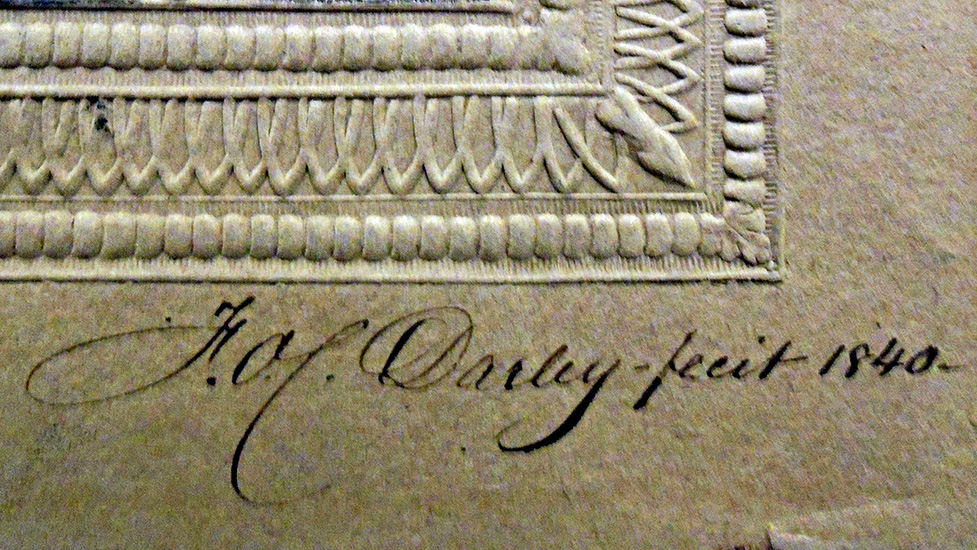

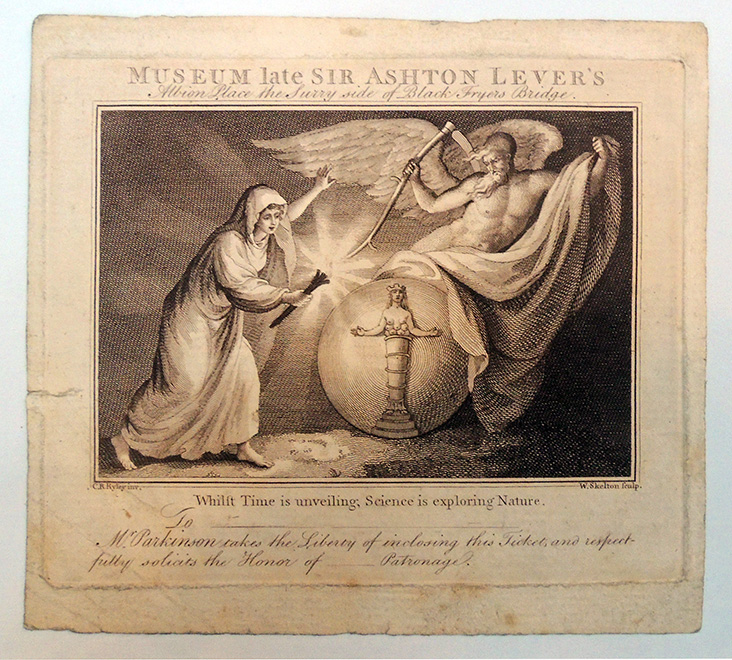

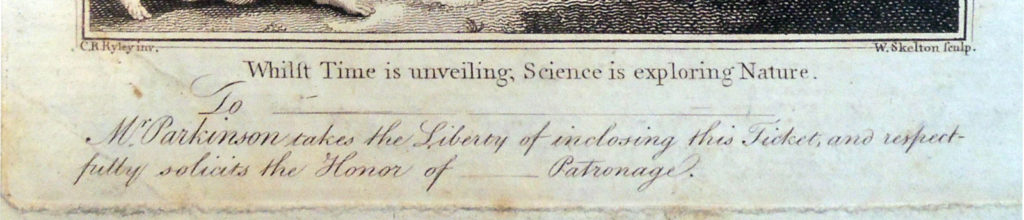

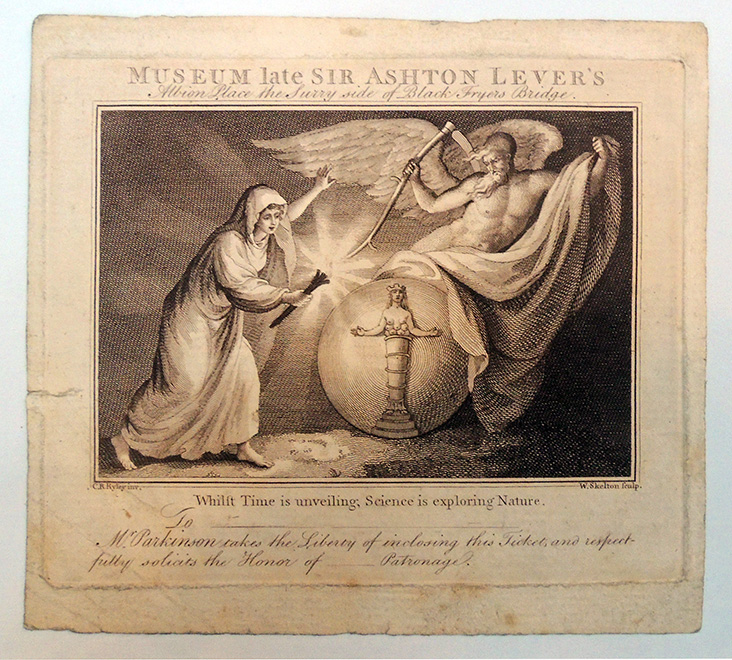

Museum late Sir Ashton Lever’s Albion Place the Surry side of Black Fryers Bridge. Admission ticket engraved by William Skelton (1762-1848) after a design by Charles Reuben Ryley (1752?-1798) [London], ca. 1788. Graphic Arts Collection 2019- in process

Museum late Sir Ashton Lever’s Albion Place the Surry side of Black Fryers Bridge. Admission ticket engraved by William Skelton (1762-1848) after a design by Charles Reuben Ryley (1752?-1798) [London], ca. 1788. Graphic Arts Collection 2019- in process

In William Hone’s 1838 The Every-day Book and Table Book; Or, Everlasting Calendar of Popular Amusements, Sports, Pastimes, Ceremonies, Etc, this ticket for the Leverian Museum is illustrated and the following explanation given:

“It seems appropriate and desirable to give the above representation of Mr. Parkinson’s ticket, for there are few who retain the original. Besides—the design is good, and as an engraving it is an ornament. And—as a memorial of the method adopted by sir Ashton Lever to obtain attention to the means by which he hoped to reimburse himself for his prodigious outlay, and also to enable the public to view the grand prize which the adventure of a guinea might gain, one of his advertisements is annexed from a newspaper of January 28, 1785.

J. R. Ashton Lever’s Lottery Tickets are now on sale at Leicester house, every day (Sundays excepted) from Nine in the morning till Six in the evening, at One Guinea each; and as each ticket will admit four persons, either together or separately, to view the Museum, no one will hereafter be admitted but by the Lottery Tickets, excepting those who have already annual admission. This collection is allowed to be infinitely superior to any of the kind in Europe. The very large sum expended in making it, is the cause of its being thus to be disposed of, and not from the deficiency of the daily receipts (as is generally imagined) which have annually increased, the average amount for the last three years being 1833l. per annum.

The hours of admission are from Eleven till Four. Good fires in all the galleries.

The first notice of the Leverian Museum is in the “Gentleman’s Magazine” for May, 1773, by a person who had seen it at Alkerington, near Manchester, when it was first formed. Though many specimens of natural history are mentioned, the collection had evidently not attained its maturity. It appears at that time to have amounted to no more than “upwards of one thousand three hundred glass cases, containing curious subjects, placed in three rooms, besides four sides of rooms shelved from top to bottom, with glass doors before them.” The works of art particularized by the writer in the “Gentleman’s Magazine,” are “a head of his present majesty, cut in cannil coal, said to be a striking likeness; indeed the workmanship is inimitable—also a drawing in Indian ink of a head of a late duke of Bridgewater…”

The winner of the 1786 lottery was estate agent James Parkinson (1730-1813), who moved the collection to the “Rotunda” near Blackfriars Bridge. Our ticket dates from this time, notably the Blackfriar’s address appears in the title.

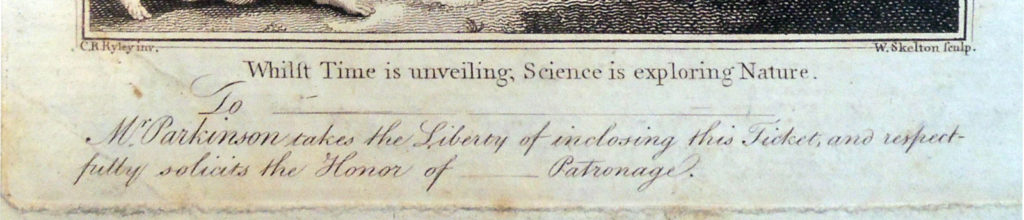

Below the image is the text: Whilst Time is unveiling, Science is exploring Nature.

Read more: J. C. H. King, “New Evidence for the Contents of the Leverian Museum,” Journal of the History of Collections, 8, no. 2 (1996): 167–86.

https://doi.org/10.1093/jhc/8.2.167

Adrienne Lois Kaeppler, Holophusicon–the Leverian Museum : an eighteenth-century English institution of science, curiosity, and art (Altenstadt, Germany: ZKF Publishers; Honolulu, HI: Distributed in the United States by Bishop Museum Press, 2011). Marquand Library Oversize AM101.L67 K34 2011q

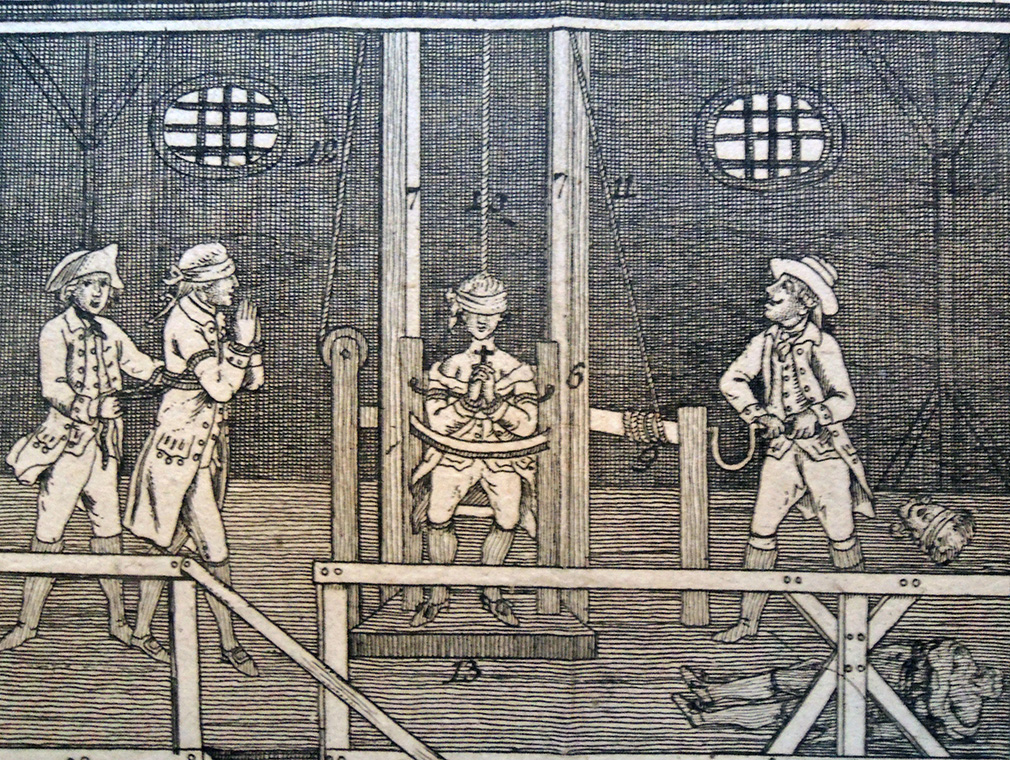

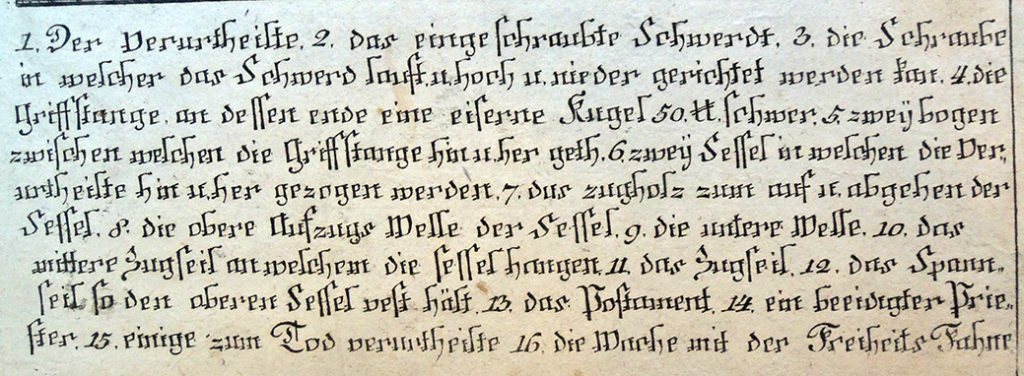

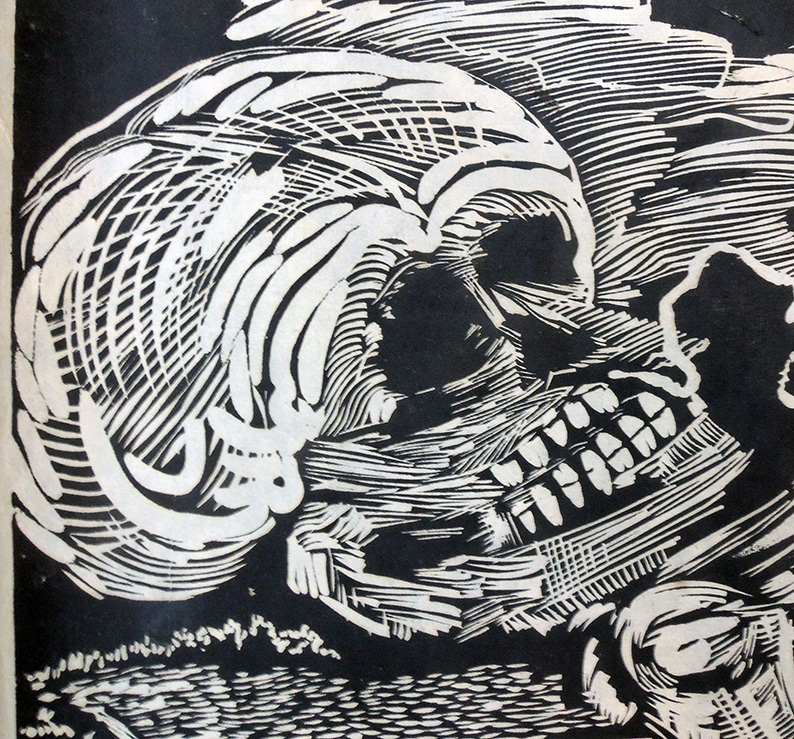

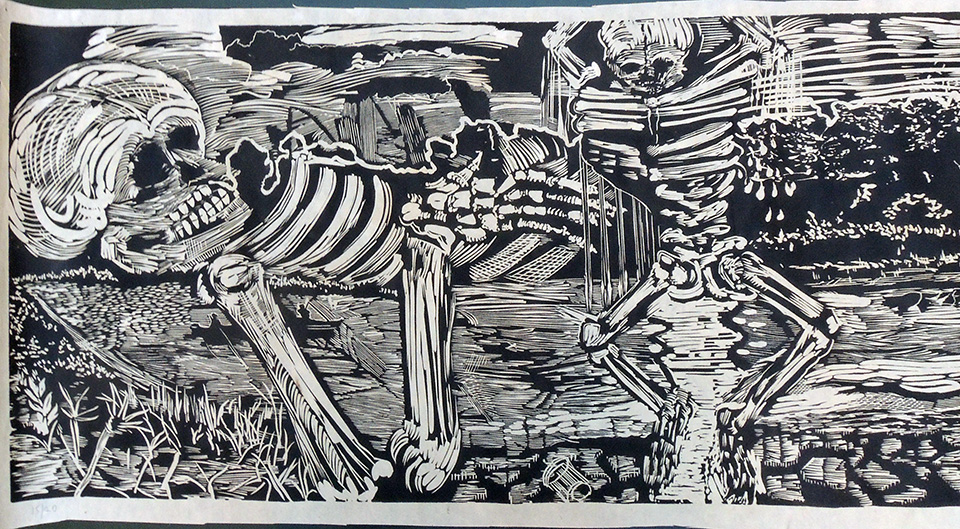

Johann Martin Will (1727 -1806), Vorstellung der Kopf Maschiene in Paris. Vermöge welcher in einer viertelstund 25 Personen könen enthauptet werden [Representation of the Head Machine by which 25 persons can be beheaded every quarter of an hour] [Augsburg: Johann Martin Will], 1792. Etching with engraving, engraved text in German and French. Graphic Arts Collection GAX 2019-in process

Johann Martin Will (1727 -1806), Vorstellung der Kopf Maschiene in Paris. Vermöge welcher in einer viertelstund 25 Personen könen enthauptet werden [Representation of the Head Machine by which 25 persons can be beheaded every quarter of an hour] [Augsburg: Johann Martin Will], 1792. Etching with engraving, engraved text in German and French. Graphic Arts Collection GAX 2019-in process