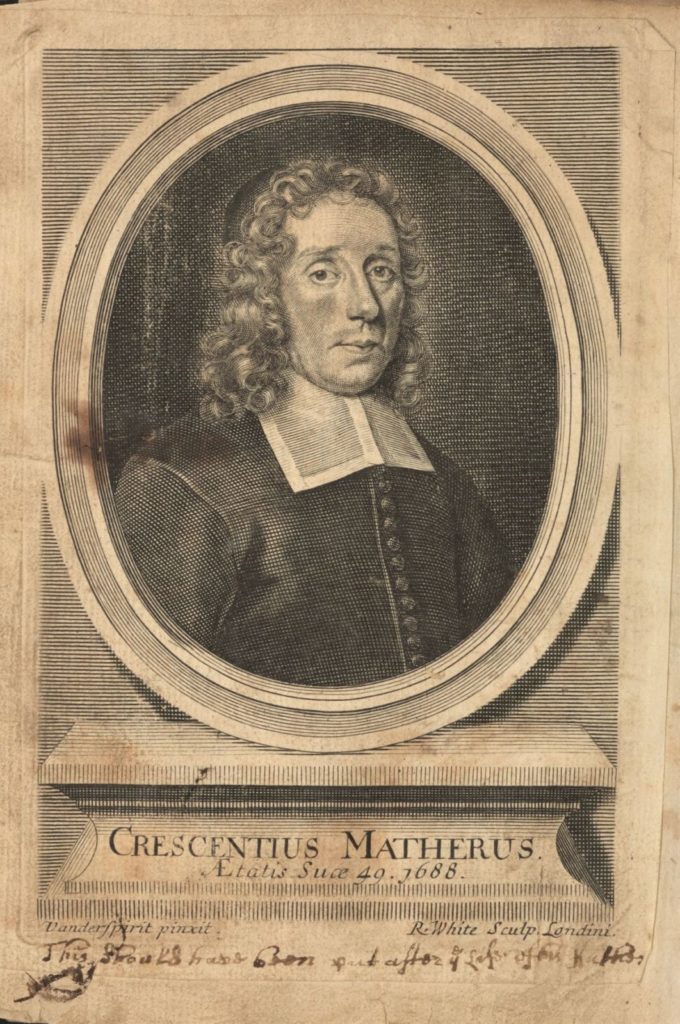

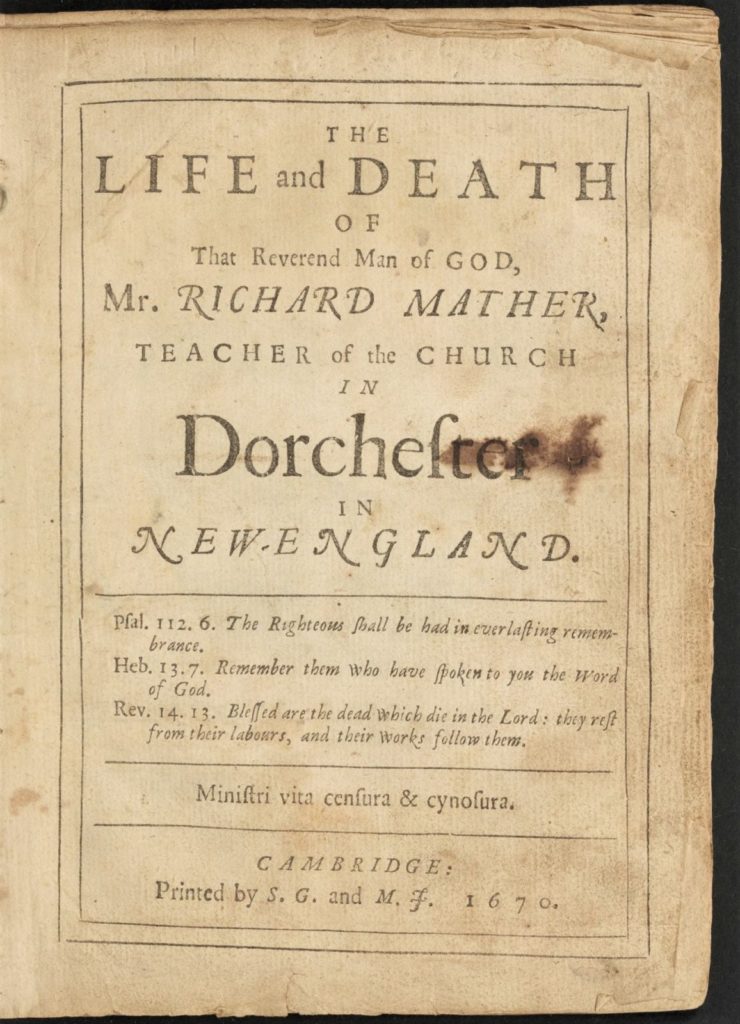

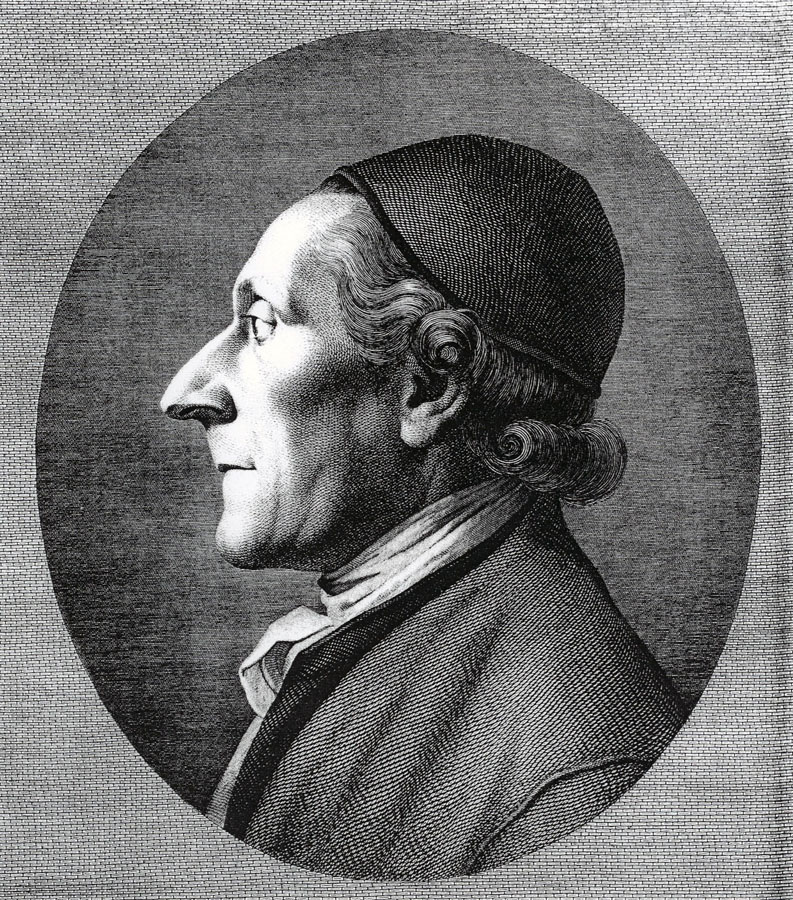

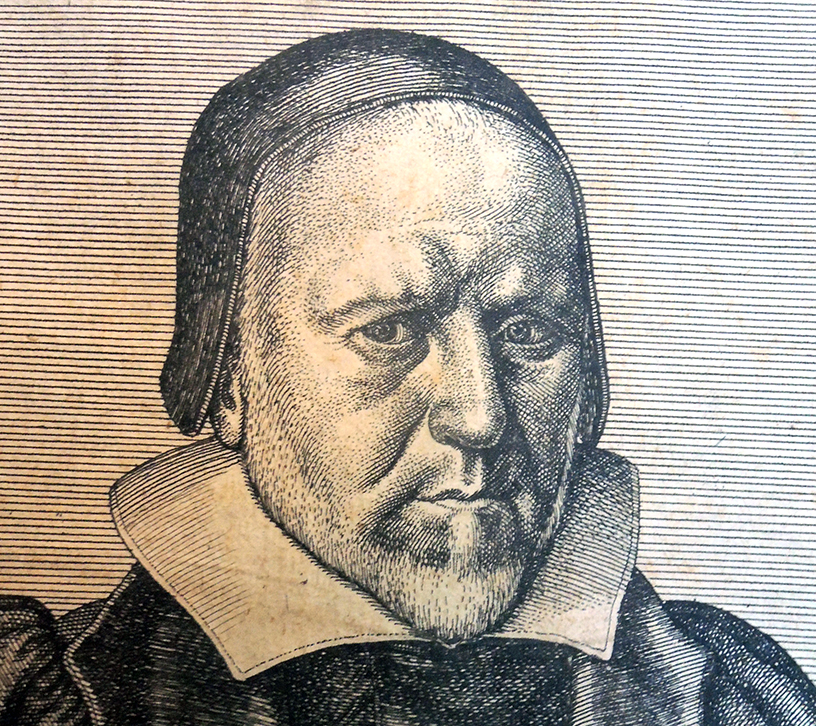

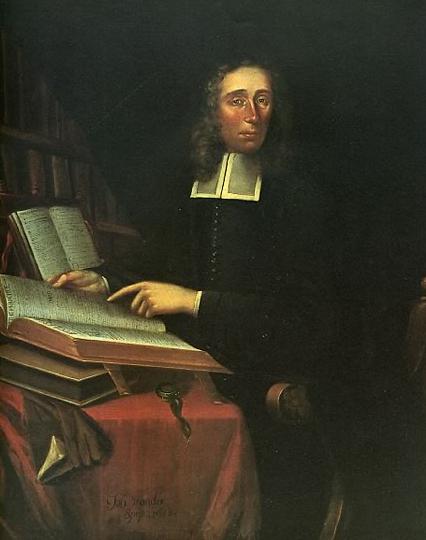

Robert White (1645-1703) after Jan van der Spriet (active 1690-1700), Crescentius Matherus [Portrait of Increase Mather], 1688. Engraving. Bound in: Increase Mather (1639-1723), The Life and Death of That Reverend Man of God, Mr. Richard Mather, Teacher of the Church in Dorchester in New-England : [seven lines of quotations] (Cambridge [Mass.]: Printed by S.G. and M.J. [i.e., Samuel Green and Marmaduke Johnson], 1670. William H. Scheide Library, 101.19

A few months ago, a live webinar was held to investigate the woodcut portrait of Richard Mather (1596-1669) by John Foster (1648-1681), recognized as the first cut printed on a European press in Colonial America. The print is assumed to have been created in honor of Mather’s death around 1670. While Princeton University Library holds a copy of that print, in William Scheide’s copy of The Life and Death of That Reverend Man of God, Mr. Richard Mather someone has inserted an engraved portrait of the author, Increase Mather, rather than the woodcut.

Thanks to our digital studio, we now have a complete surrogate copy of the volume along with the engraving to study at home. https://catalog.princeton.edu/catalog/4696592

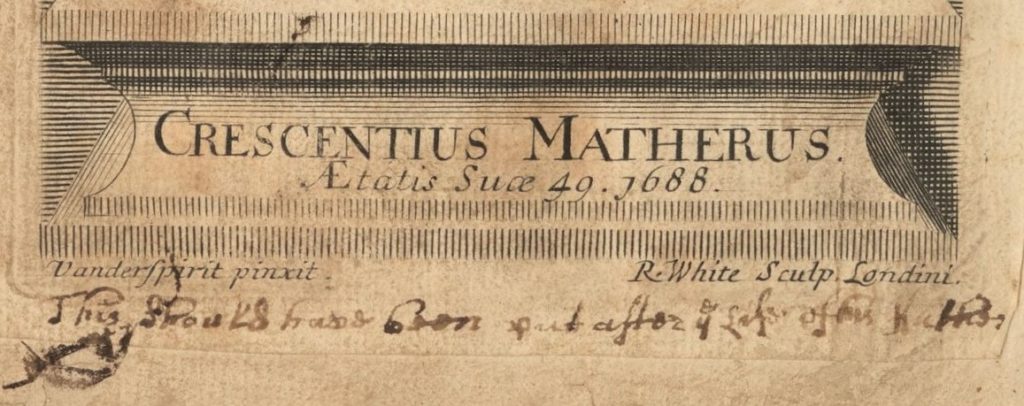

The Scheide volume has a dedication signed: Increase Mather. Boston N.E. Septemb. 6. 1670. The pasted in engraving holds the inscription: Crescentius Matherus. Aetatis Suae 49. 1688. Vanderspirit pinxit. R. White Sculp. Londini. This tells us that it was engraved by Robert White (1645-1703) after a drawing by Jan van der Spriet (active 1690-1700),

The Scheide volume has a dedication signed: Increase Mather. Boston N.E. Septemb. 6. 1670. The pasted in engraving holds the inscription: Crescentius Matherus. Aetatis Suae 49. 1688. Vanderspirit pinxit. R. White Sculp. Londini. This tells us that it was engraved by Robert White (1645-1703) after a drawing by Jan van der Spriet (active 1690-1700),

The portrait shows Increase Mather, aged 49, with long hair, wearing skull-cap and bands. According to Proceedings of the Massachusetts Historical Society (1894), “Mather’s portrait was painted in 1688 [see below], during his visit to England, where, as an agent of the Massachusetts Colony, he had gone in the spring of that year. The artist was John vander Spriett, a Dutch mezzotint engraver of little note, who had studied under Verkolie at Amsterdam, where he had painted a few portraits. He afterward went to London, and died there about the year 1700.”

Presumably Dr. Mather, on his return home in the spring of 1692, brought back to Boston this painting of himself. Inasmuch as his eldest child, Dr. Cotton Mather, inherited the larger part of his estate, it is very likely that the picture passed into that son’s possession, and thence into the hands of his grandson Samuel. Within a few months after Dr. Mather’s portrait was painted in London, it was engraved by Robert White, an English artist of some note (born 1645, died 1704), who had made many other likenesses of distinguished persons.

It is a small copperplate engraving, about six inches by four in size, representing the bust in an oval frame, and the whole resting on a pedestal, and bears the legend “Crescentius Matherus. AEtatis Suae 49. 1688.” In the two lower corners, below the pedestal, are the following words, in small script: “Vanderspirit pinxit. R. White Sculp. Londini.” It is of excellent workmanship, the hatching is soft and delicate, and the handling of the hair graceful. While the engraver has taken some liberties in his production and has slightly changed the pose of the figure, it is evident that he followed this identical portrait.

https://www.masshist.org/database/3281

https://www.masshist.org/database/3281

According to White’s biography written for the British Museum, the artist was the “foremost pupil of [David Loggan, 1634–1692], and inherited his position as the leading line-engraver for the print trade. His earliest print was made in 1666, and his last in 1702. His output was huge, and has never been fully catalogued. [George Vertue, 1684-1756]‘s list, reproduced by Walpole, has several hundred plates. Vertue got some information from White’s son, George: ‘Robert White Engraver did not only learn of Mr Loggan but from his infancy had an inclination to drawing & made essays in engraving and etching before he knew Loggan. He drew many buildings for Loggan & engrav’d, besides he imploy’d much of his time in drawing from the life black led upon vellum’”.

While most of White’s portraits are found as frontispieces, “A small number he published himself at his house in Bloomsbury Market …. He is said to have charged about £4 for a small plate, but up to £30 for a large one.”