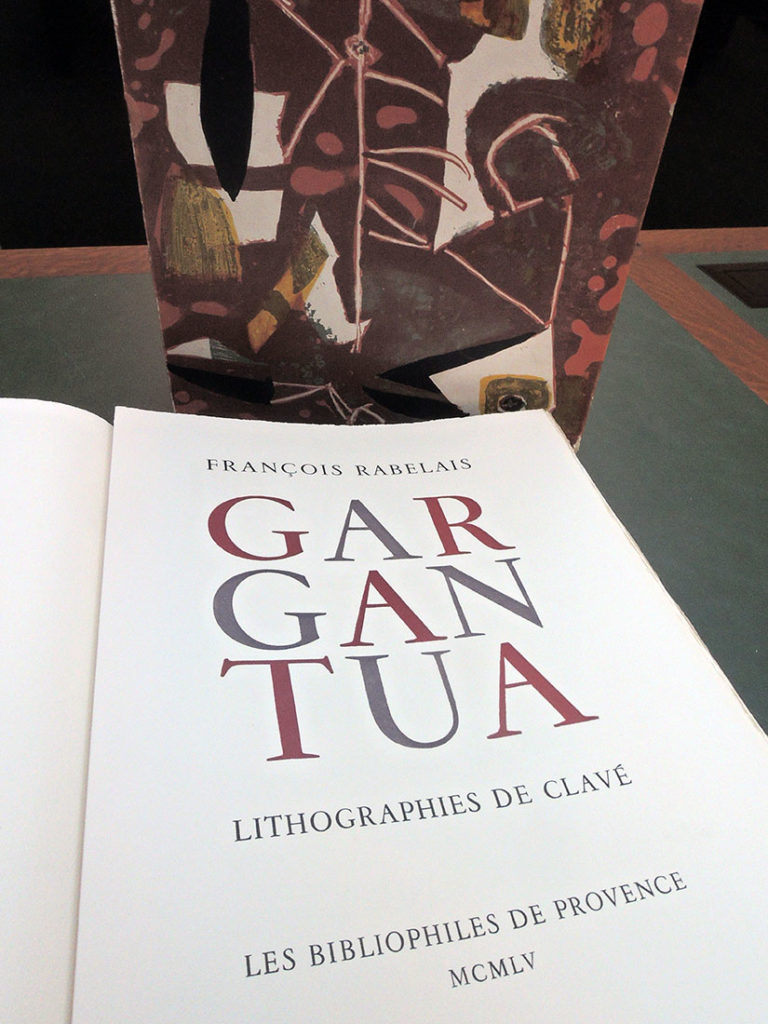

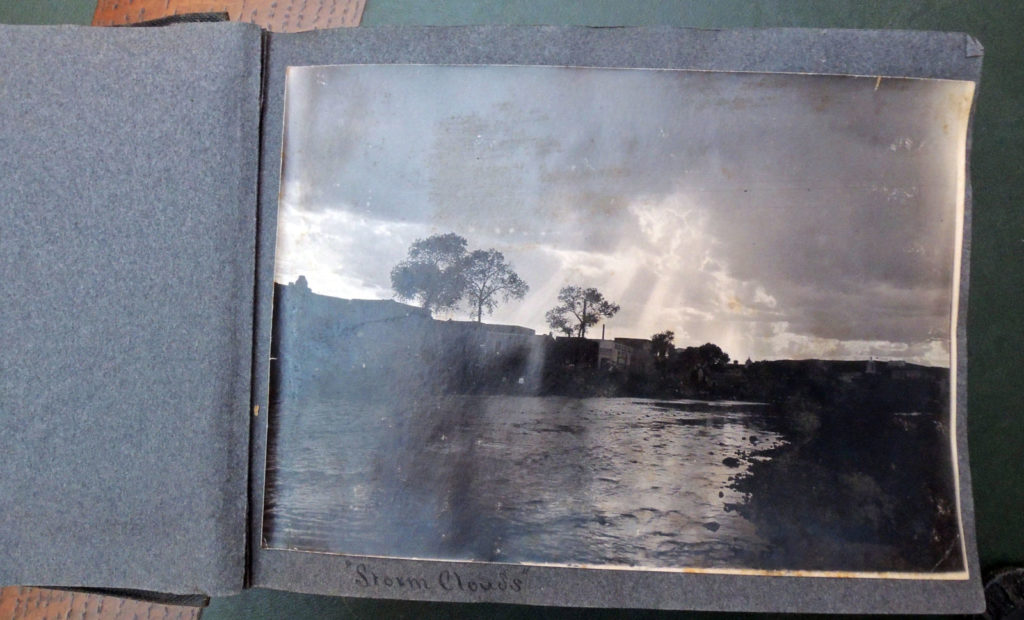

A trip to Jean Baptiste Colbert’s estate at Sceaux, south of Paris, helped to clarify the two illusionistic ceiling designs created in 1674 by Charles Le Brun for Colbert. One fresco was completed for the dome of Colbert’s chapel and a second was painted on the ceiling of the Pavilion of the Dawn (Pavillon de l’Aurore). While we can visit the Pavilion today [seen above] and appreciate Le Brun’s amazing design, the original castle and chapel were destroyed in 1803 along with that second work by Le Brun.

A trip to Jean Baptiste Colbert’s estate at Sceaux, south of Paris, helped to clarify the two illusionistic ceiling designs created in 1674 by Charles Le Brun for Colbert. One fresco was completed for the dome of Colbert’s chapel and a second was painted on the ceiling of the Pavilion of the Dawn (Pavillon de l’Aurore). While we can visit the Pavilion today [seen above] and appreciate Le Brun’s amazing design, the original castle and chapel were destroyed in 1803 along with that second work by Le Brun.

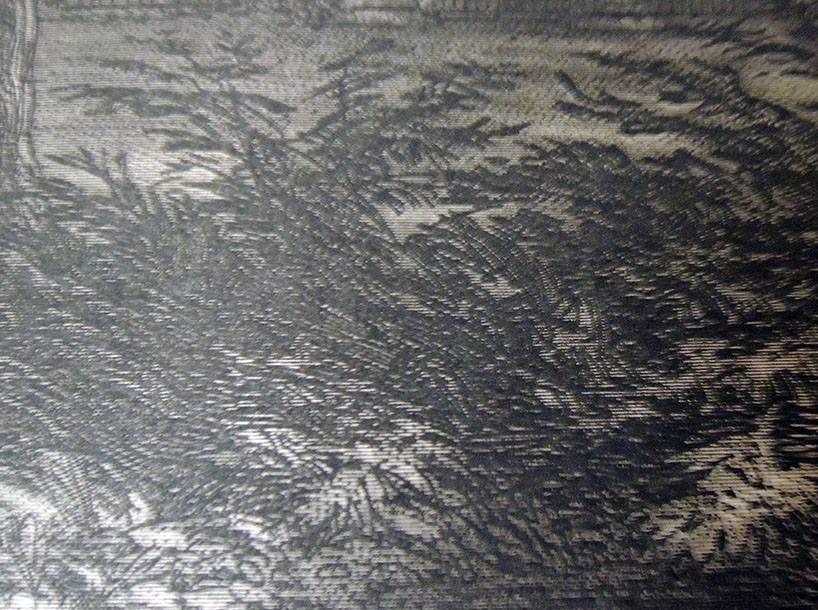

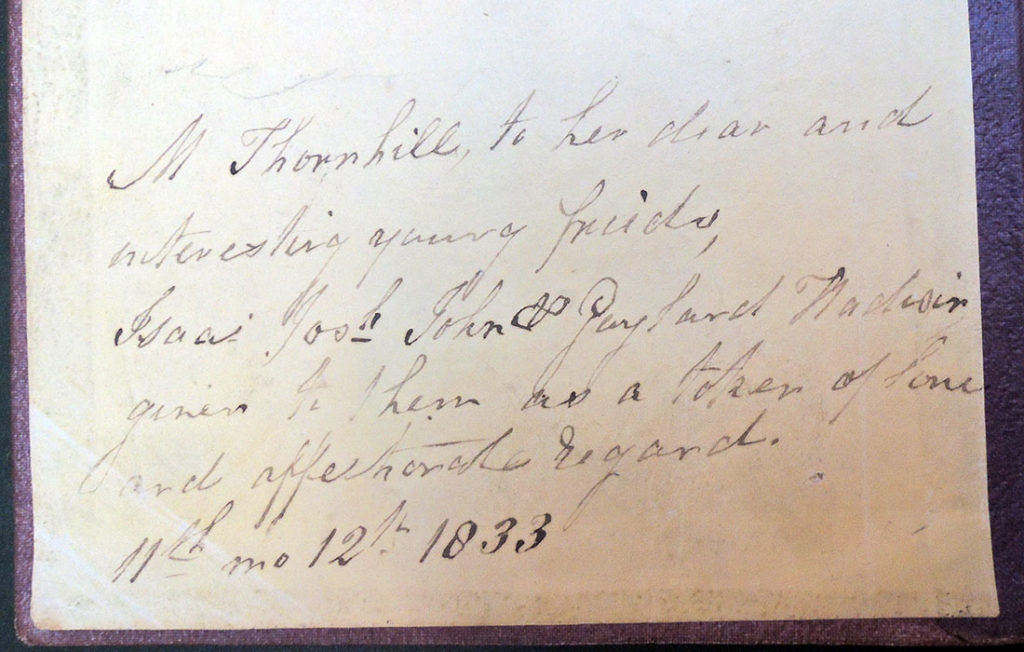

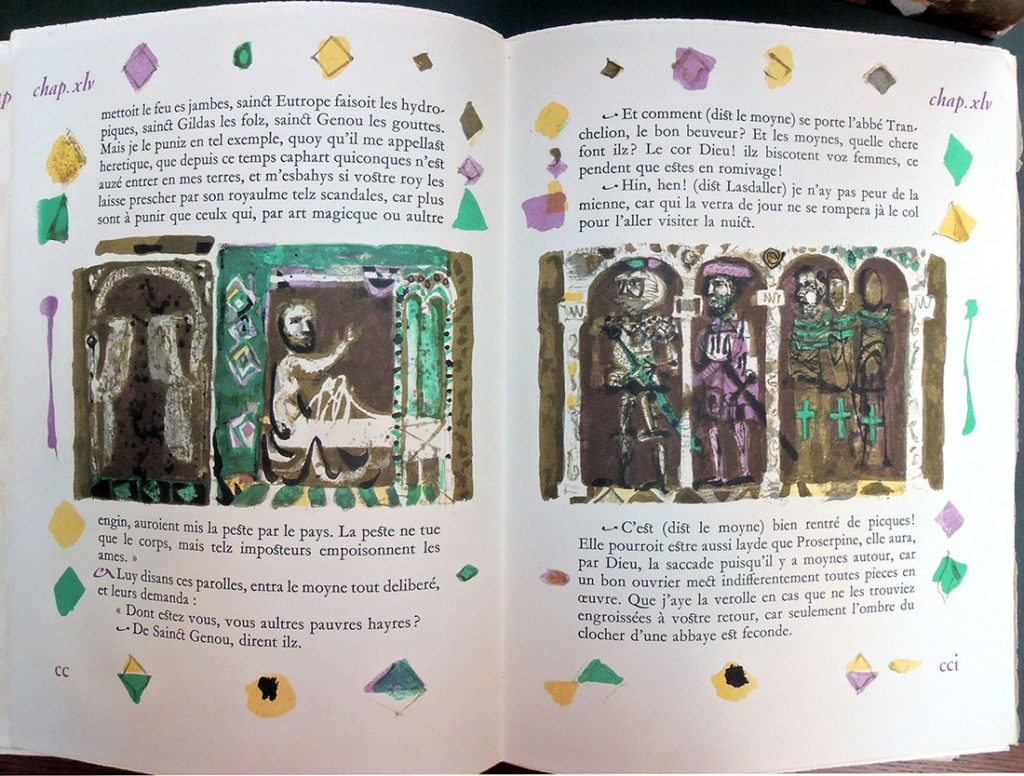

Happily, the chapel design, known as the Triumph of the New Testament, may be studied thanks to a painted copy by Le Brun’s assistant François Verdier [below], as well as the set of five engravings by Gérard Audran, held in the Graphic Arts Collection.

Gérard Audran (1640-1703) after Charles Le Brun (1619-1690), [Set of five plates, known as Triumph of the New Testament over the Old Testament], 1681. Etching and engraving. GA 2012.01256-01260.

Gérard Audran (1640-1703) after Charles Le Brun (1619-1690), [Set of five plates, known as Triumph of the New Testament over the Old Testament], 1681. Etching and engraving. GA 2012.01256-01260.

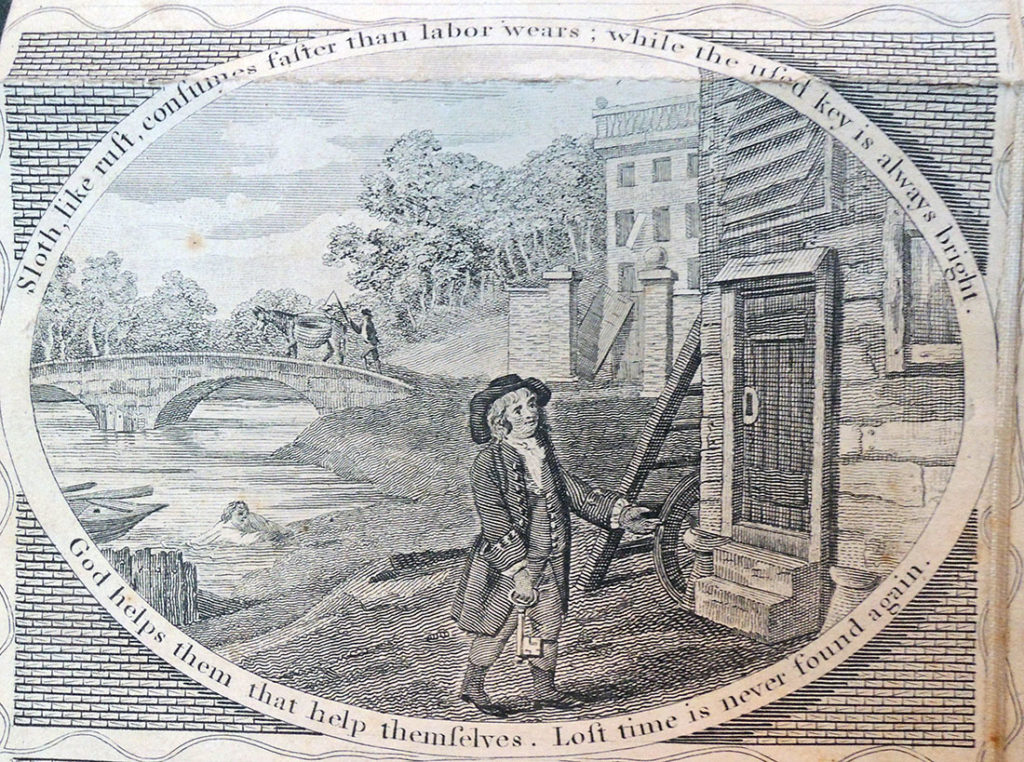

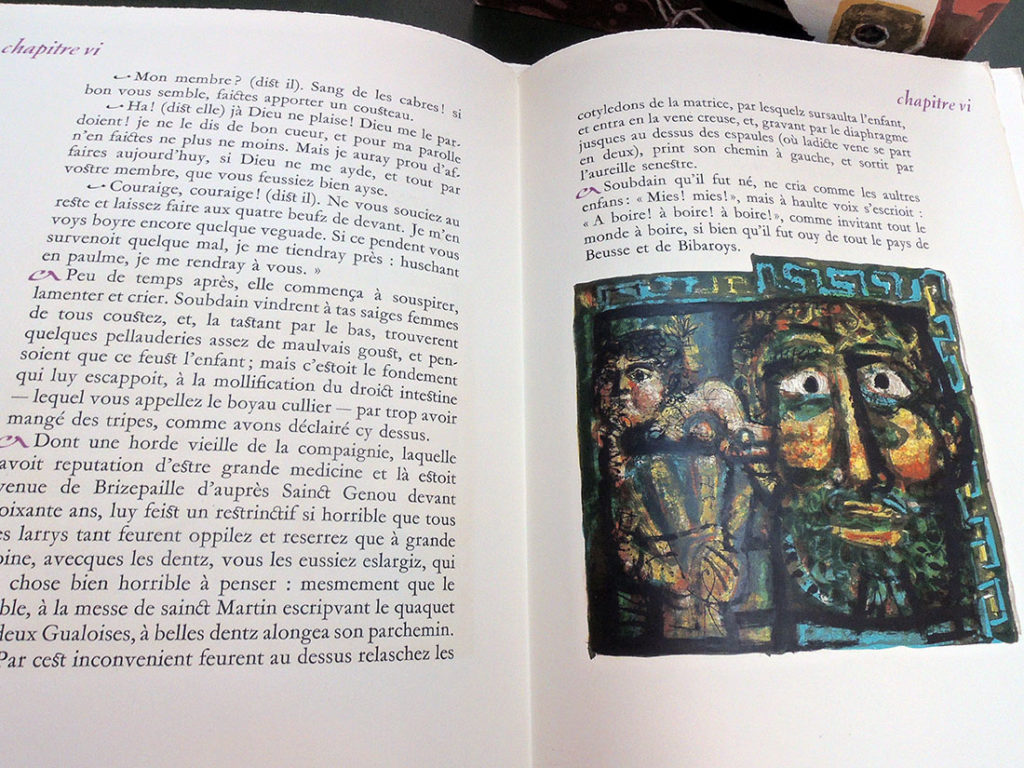

1. “Car. Le Brun Regis Pictor primarius, udo tectorio pinxit in Capella Castelli vulgo de Seaux, Girardus Audran aeri incidit, 1681.” Depicts angels bearing the Ark of the Covenant.

2. “Le Pere Eternel porte sur les ailes des Anges, prononeant ces paroles au baptesme de Iesus Christ, voicy mon fils bien aime &c.” Depicts God the Father on the wings of angels.

3. “Peint a fraisque dans la voute de la Chapelle du Chasteaux de Sceaux.” Depicts the adoring angels.

4. “Pater Aeternus sedens super pennas Angelorum, haec verba in Baptismate Iesu Christi proferens, Hic est Filius meus dilectus &c.” Depicts the baptism of Jesus Christ.

5. Untitled [center section was perhaps not meant to be cut apart]

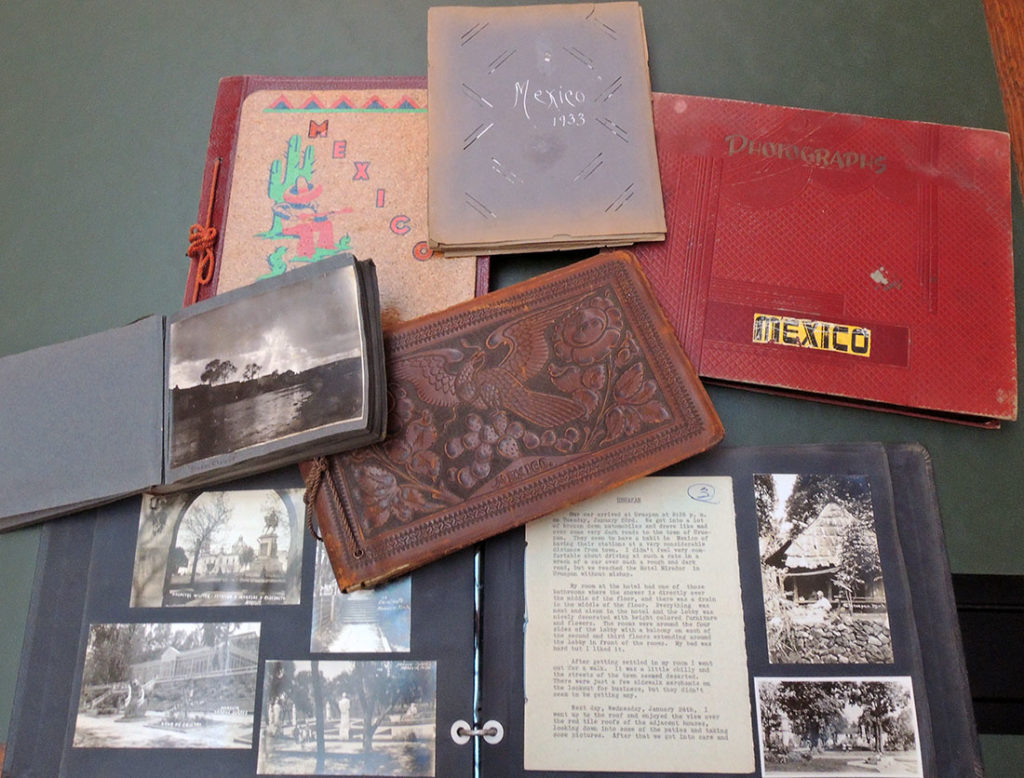

Above is the fresco in the Pavilion of the Dawn, described below in the estate’s official website:

Above is the fresco in the Pavilion of the Dawn, described below in the estate’s official website:

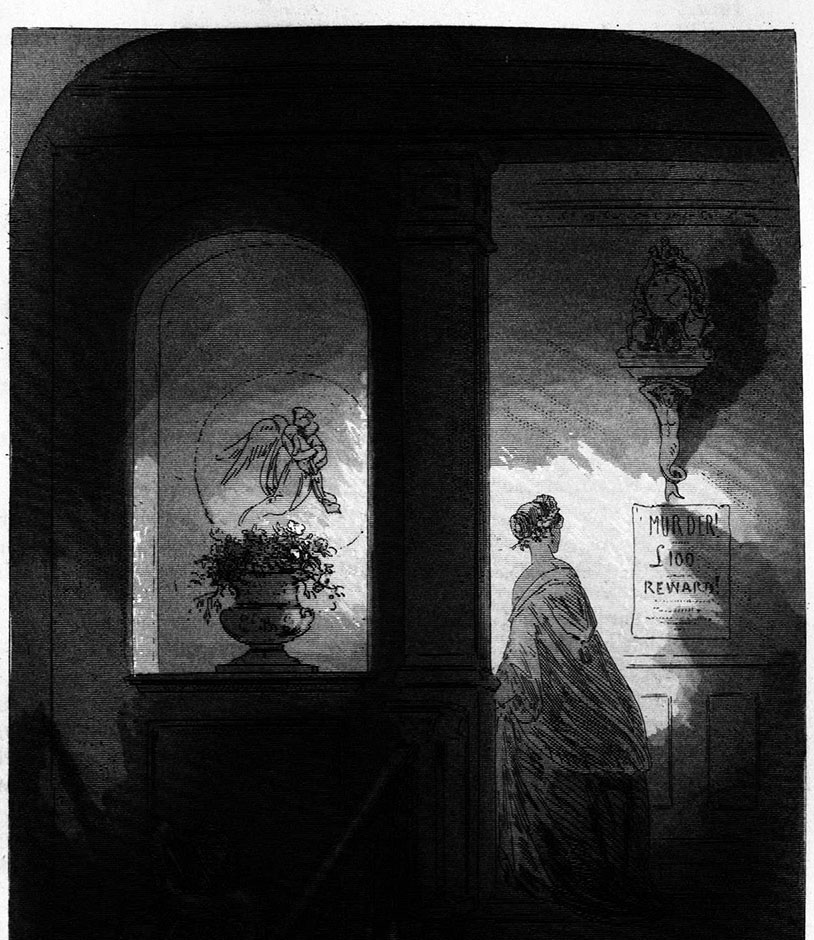

“The Pavillon de l’Aurore houses one of the most remarkable compositions by Charles Le Brun, after Vaux-le-Vicomte and before the great sets of Versailles. Jean-Baptiste Colbert, Baron of Sceaux, Superintendent of Buildings, Arts and Manufactures, in 1664, built in the early 1670s, this elegant garden pavilion, an expression of his taste for an architecture called classical. It was the setting for a remarkable pictorial composition on the theme of Dawn, preceding the sunrise, work of Charles Le Brun, first painter of King Louis XIV.

This famous cupola, elaborated before the large sets of Versailles, dominates a living room rotunda framed by two quadrangular cabinets. In 1677, before the members of the French Academy, Colbert read a long description in verse, composed by Philippe Quinault, commenting on the decor of this “Cabinet of Dawn”. Later, the sovereign and the court admired the building at a big party ordered by Jean-Baptiste Colbert, Marquis of Seignelay, son of the previous, in 1685.

In the years 1714 and 1715, Louise-Bénédicte de Bourbon, duchess Maine chooses this graceful building for the scenography of its festivals, “The Great Nights of Seals”. The west facade of the Pavillon de l’Aurore presents a balanced game of lines and an elegant harmony of curves formed by the basin and the fountain, a kind of water buffet, the two steps of access to the perron, the front-body , the dome and the balustrades. A restoration of architecture and interior decoration was carried out in the last two decades of the twentieth century.”

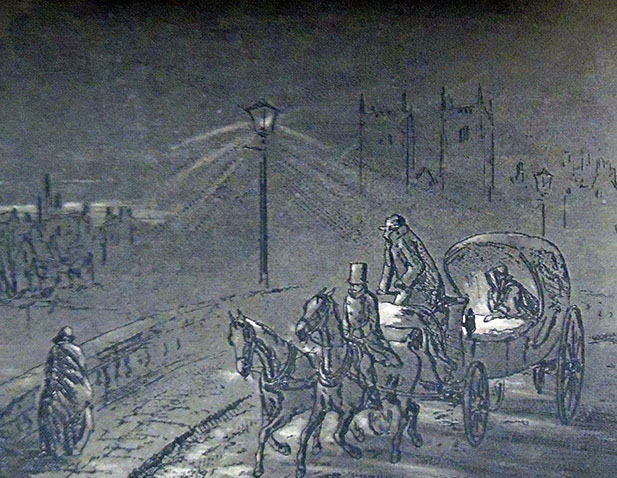

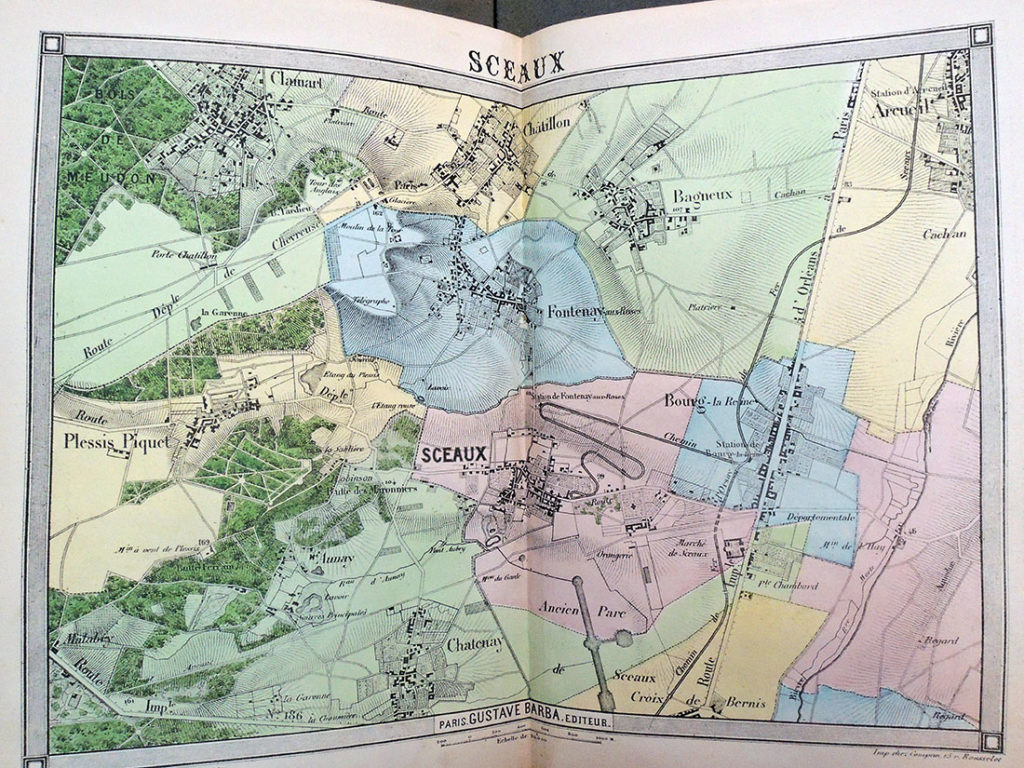

Emile de La Bédollière (1812-1883), Histoire des environs du nouveau Paris; illustrations de Gustave Doré; cartes topographiques dessinées et gravées par Ehrard (Paris: G. Barba, 8, rue Cassette, 8, [1861?]) ReCAP – Rare Books 1514.552

http://domaine-de-sceaux.hauts-de-seine.fr/ledomaine/le-pavillon-de-laurore/

http://domaine-de-sceaux.hauts-de-seine.fr/ledomaine/le-pavillon-de-laurore/