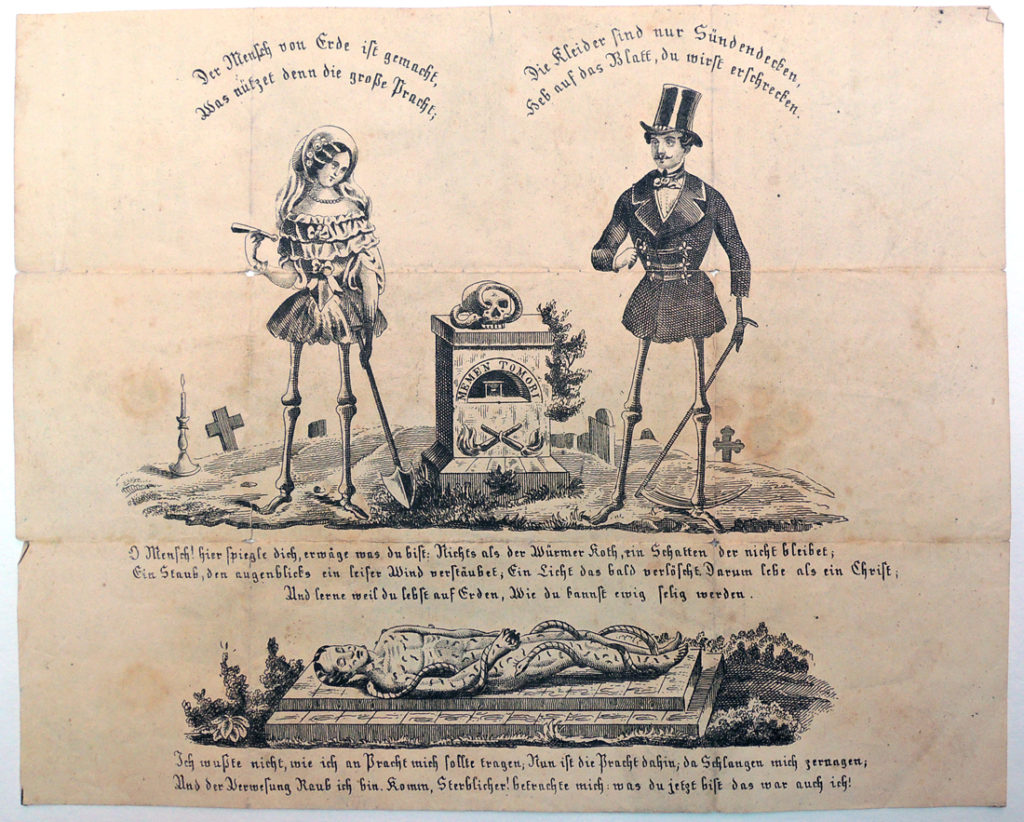

Alexandra Exter (1882-1949), Design for two theater costumes [possible design for the ballet Don Juan], ca. 1927. Pencil, watercolor, gouache on paper. Presented by Simon Lissim. RBSC Theater Collection – in process

Alexandra Exter (1882-1949), Design for two theater costumes [possible design for the ballet Don Juan], ca. 1927. Pencil, watercolor, gouache on paper. Presented by Simon Lissim. RBSC Theater Collection – in process

Among a group of drawings being conserved and rehoused, this design was discovered that may have been created for the production of Don Juan given by Anna Pavlova’s company at the Opernhaus, Cologne in 1927.

The Oxford Art biography lists Exter as a “Russian painter and designer of Polish birth.” After traveling to Paris in 1908, she “became acquainted with Picasso, Braque, Guillaume Apollinaire, Max Jacob and with the Italian Futurists Filippo Marinetti, Giovanni Papini and Ardengo Soffici (with whom she shared a studio in 1914) . . . In 1924 Exter emigrated and settled in Paris, teaching with Fernand Léger and in her own studio.

. . . [Exter] worked extensively in the theatre and continued to experiment, beginning, at this time, to make inventive theatrical puppets. In 1929 she used tubes of light to create an elegant, almost dematerialized spatial setting for the ballet Don Juan . . . .”

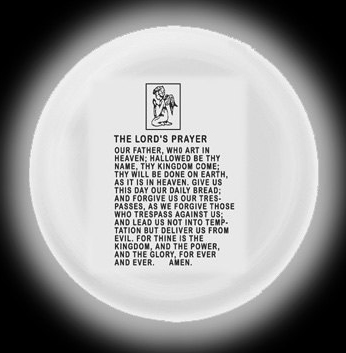

The drawing comes into the department thanks to Exter’s colleague and biographer Simon Lissim (1900-1981). Raymond Lister described Lissim, “who belonged unmistakably to the twentieth century, was nevertheless a modern example of Renaissance man, for his achievements were spread over a wide spectrum with theatrical décor at one end and porcelain designs at the other. Between were paintings in gouache and scraperboard, and designs for crystal, cutlery and jewelry.”

The drawing comes into the department thanks to Exter’s colleague and biographer Simon Lissim (1900-1981). Raymond Lister described Lissim, “who belonged unmistakably to the twentieth century, was nevertheless a modern example of Renaissance man, for his achievements were spread over a wide spectrum with theatrical décor at one end and porcelain designs at the other. Between were paintings in gouache and scraperboard, and designs for crystal, cutlery and jewelry.”

Around 1941, Lissim settled in New York City and was appointed head of the Art Education Project in the New York Public Library, later joining City University of New York as a Professor in Art History.

See also:

Simon Lissim (1900-1981), Simon Lissim [with] Raymond Cogniat, Georges Lechevallier-Chevignard, Louis Réau (Paris: Éditions du Cygne, 1933). Illustrations include 16 color plates rendered by the pochoir process. Princeton copy is no. 35 in the Charles Rahn Fry Pochoir Collection. Graphic Arts Collection Oversize 2003-0377Q