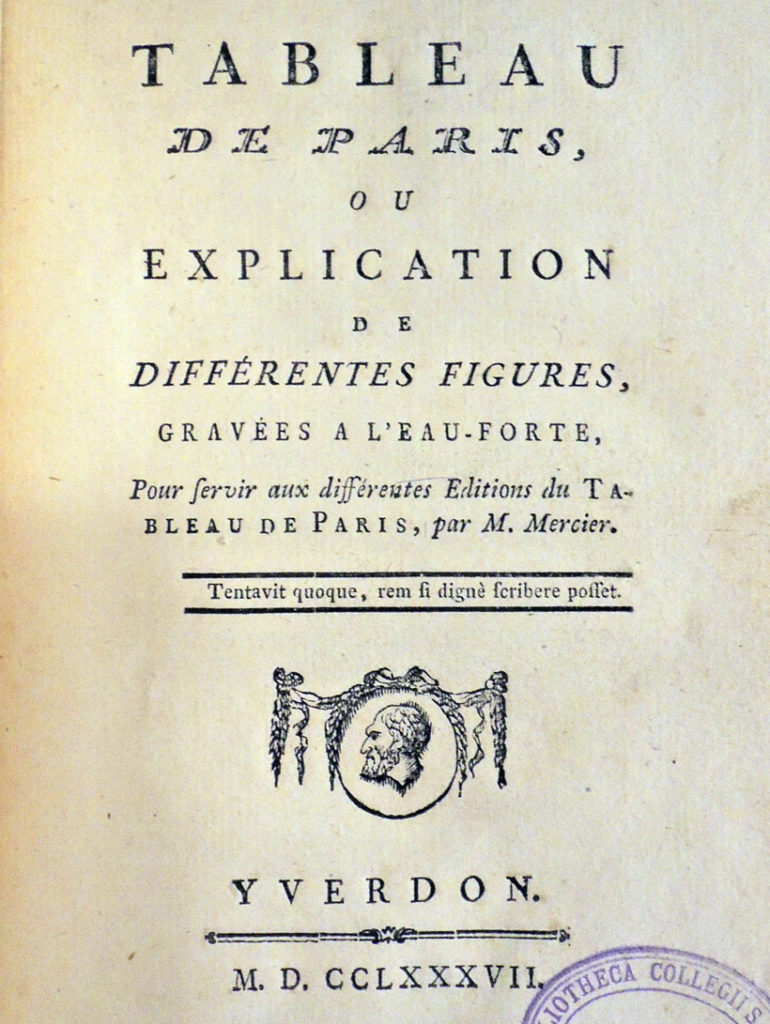

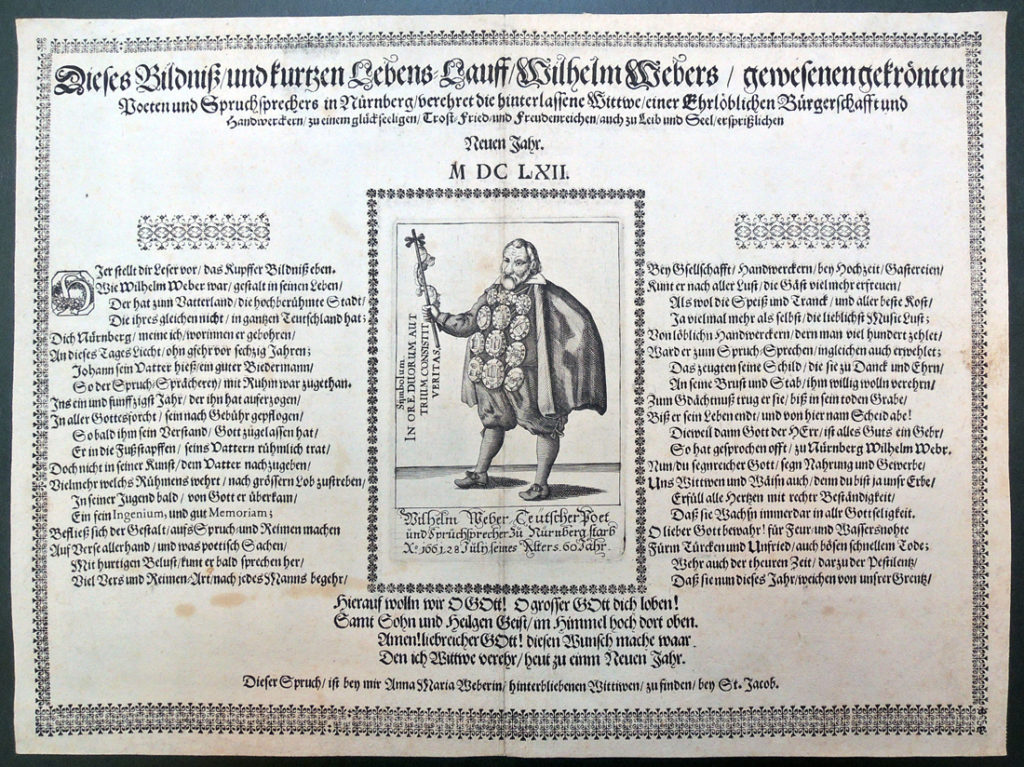

At the beginning of Balthasar Anton Dunker’s 1787 collection of etchings designed to “serve the different editions” of Louis-Sébastien Mercier’s Panorama of Paris, there is a notice to the public stating (roughly translated): “The Publishers of this series of little sketches for the Panorama of Paris, have thought it would be very agreeable to the public to see beside the most interesting Chapters of this book, figures which represented to the eyes what Mr. Mercier said with so much elegance & precision.”

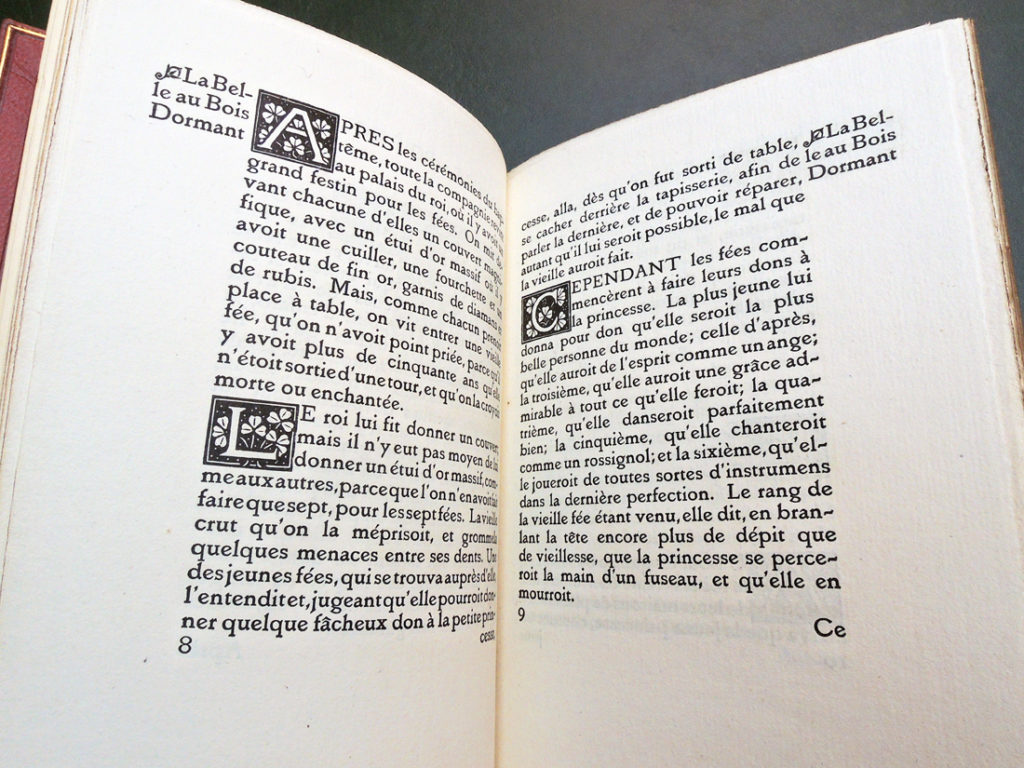

The name of the publisher who wrote this note is conveniently omitted since Mercier was explicit in his disdain of painters, sculptors, engravers, and the other visual artists of the day. All eight volumes of Mercier’s book were specifically published without illustrations or decoration of any kind.

In The Unfinished Enlightenment [Firestone PQ265 .S72 2010], historian Joanna Stalnaker notes:

“Tableau de Paris [is] peppered with venomous condemnations of painting and painters. Painting, the ‘idiot sister’ of poetry, is ‘a childish production [un enfantillage] of the human mind, a continually impotent enterprise that is in most cases laughably intrepid.’ And painters are ‘the most useless men in the world, charging exorbitant prices for an art that in no way interests the happiness, tranquility, or even the pleasures [les jouissances] of civil society; a cold and false art of which any true philosopher will sense the inanity.” .

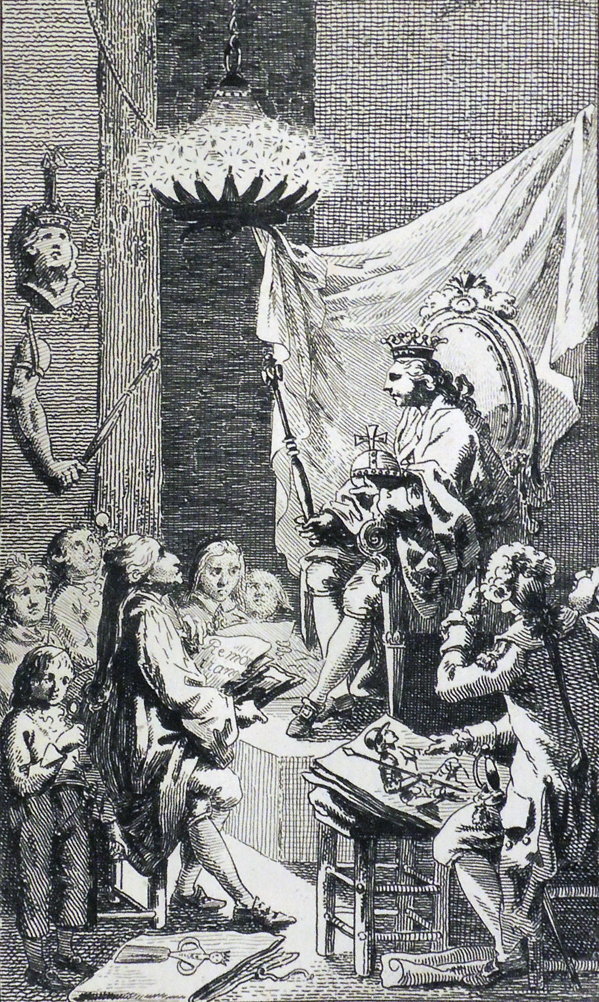

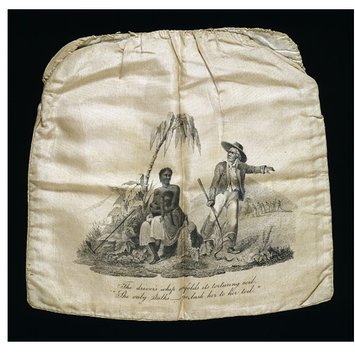

On the other hand, Mercier often equates his writing with painting, stating “I held nothing but the brush of the painter in this work” and referring to his text as “mots-couleurs” or word colors. Dunker must have noticed this and for the frontispiece to his accompanying etchings, the artist begins with a personification of Paris turning away from a physical painting labeled “Tableau of Paris.” The caption: “Let’s put our brushes together! Let’s see black!”

The chapters from Mercier’s book chosen to be illustrated by Dunker are predominantly those dealing with the arts, leading readers to wonder whether the artist is having fun at the author’s expense, rather than simply illustrating him. Perhaps Dunker is the satyr on the frontispiece, peering out at Mercier from behind his canvas.

Balthasar Anton Dunker (1746-1807), Tableau de Paris, ou explication de différentes figures, gravées à l’eauforte, pour servir aux différentes éditions du Tableau de Paris (Yverdon: [publisher not identified], 1787). SAX DC729. D765 1787

Louis-Sébastien Mercier (1740-1814), Tableau de Paris (Amsterdam: [s.n.], 1782-1783). ReCAP Ex 1514.635.1782 v.1-8