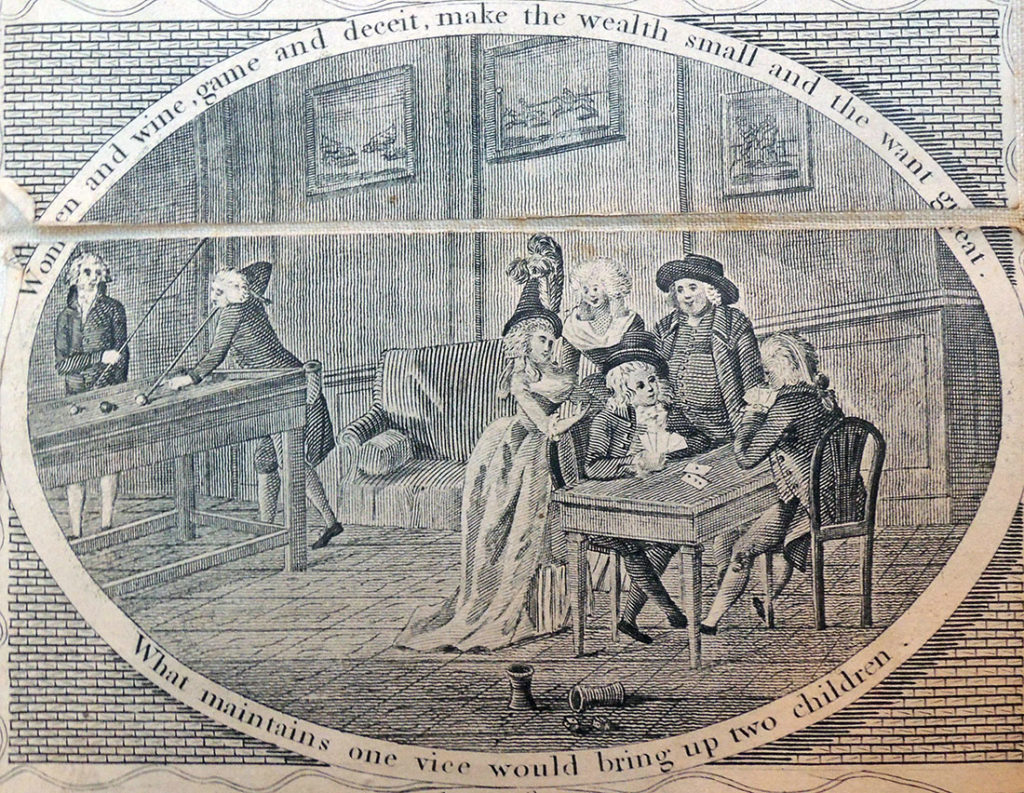

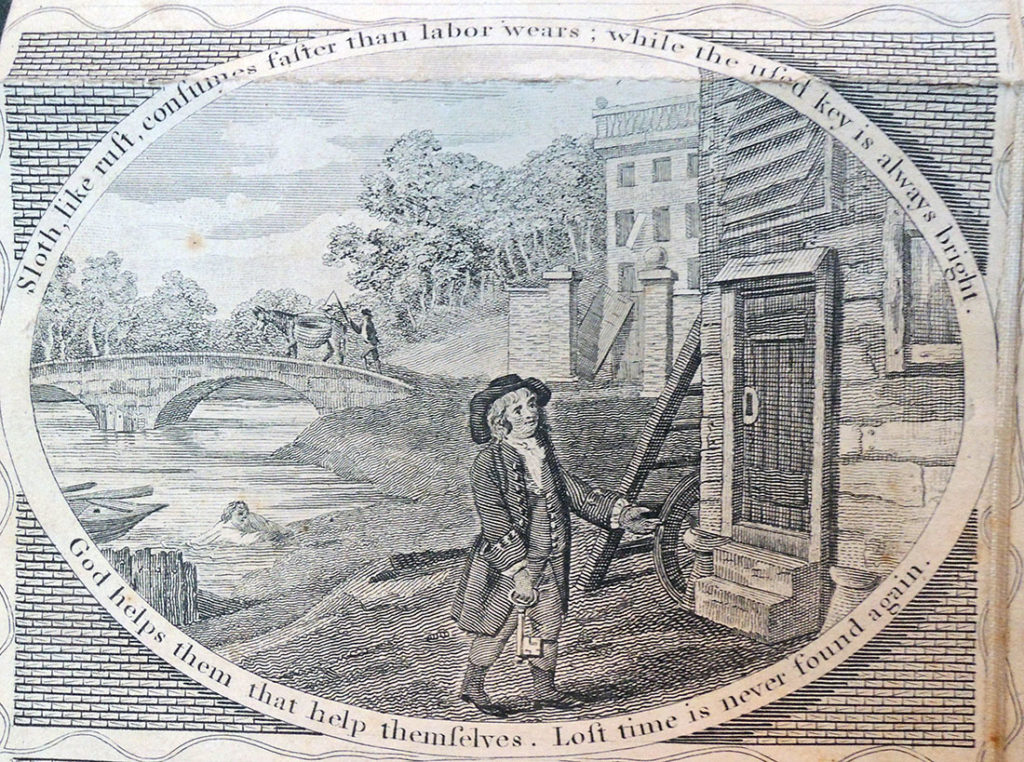

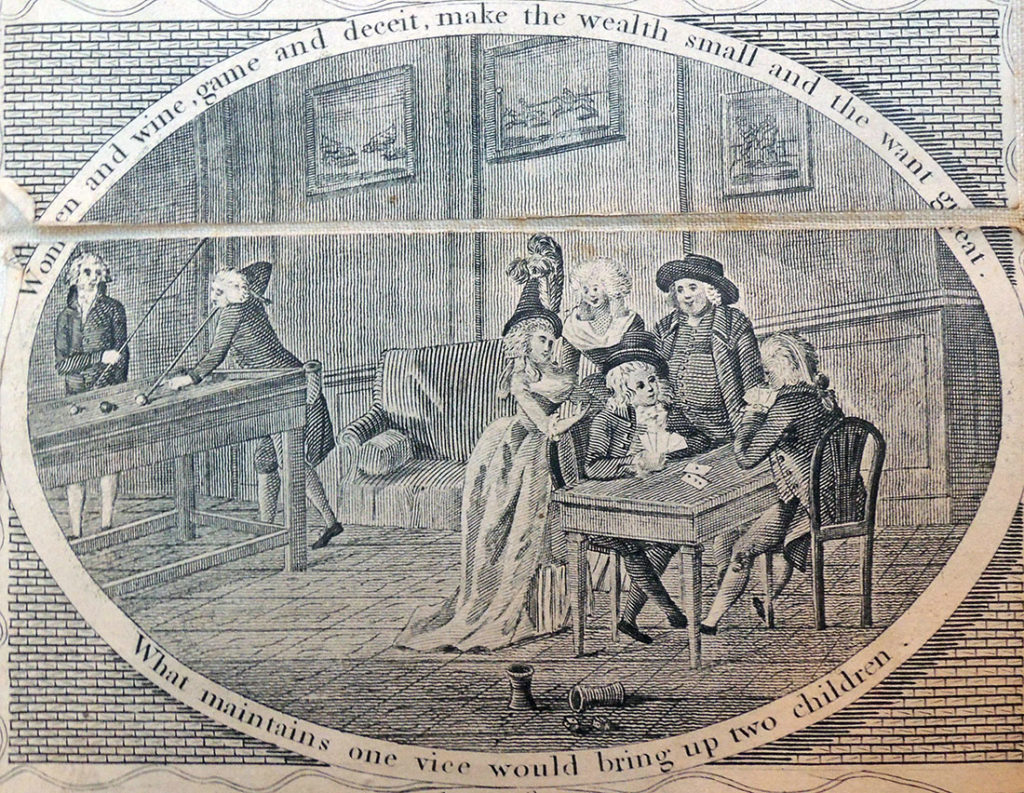

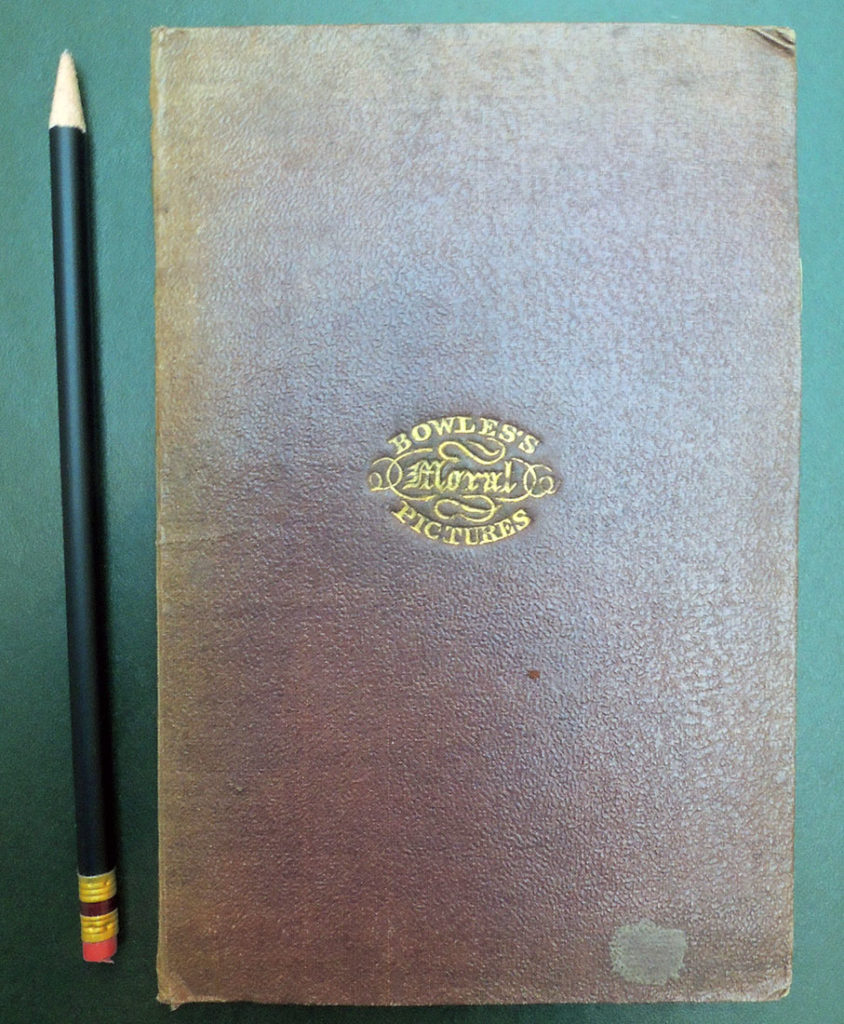

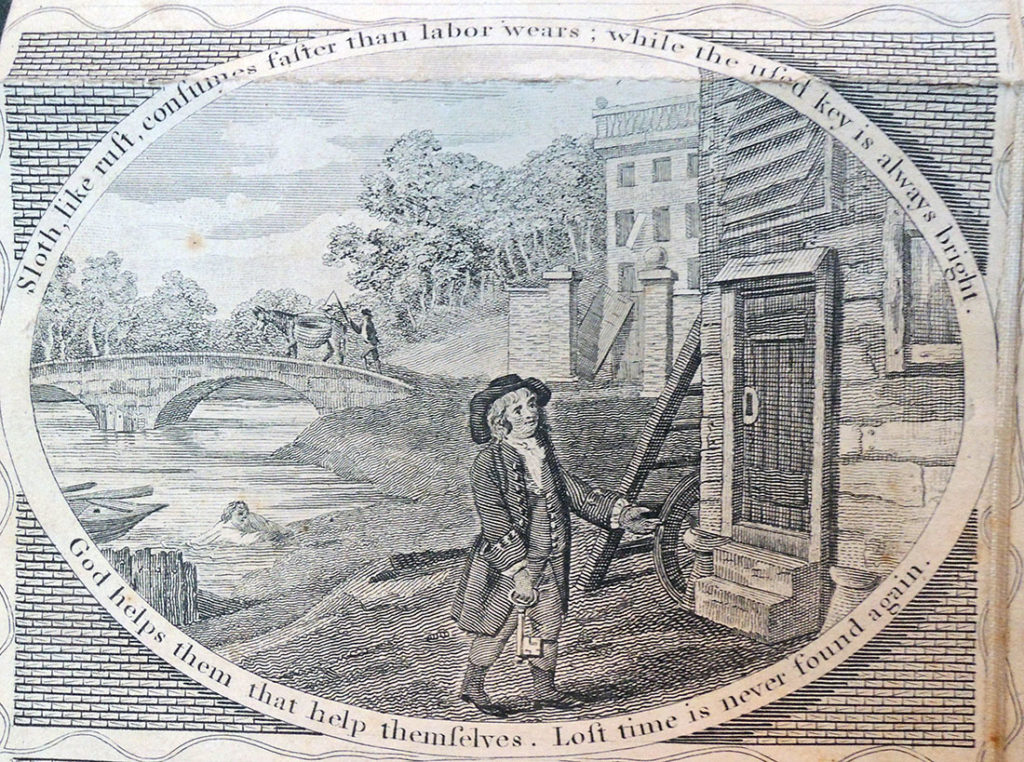

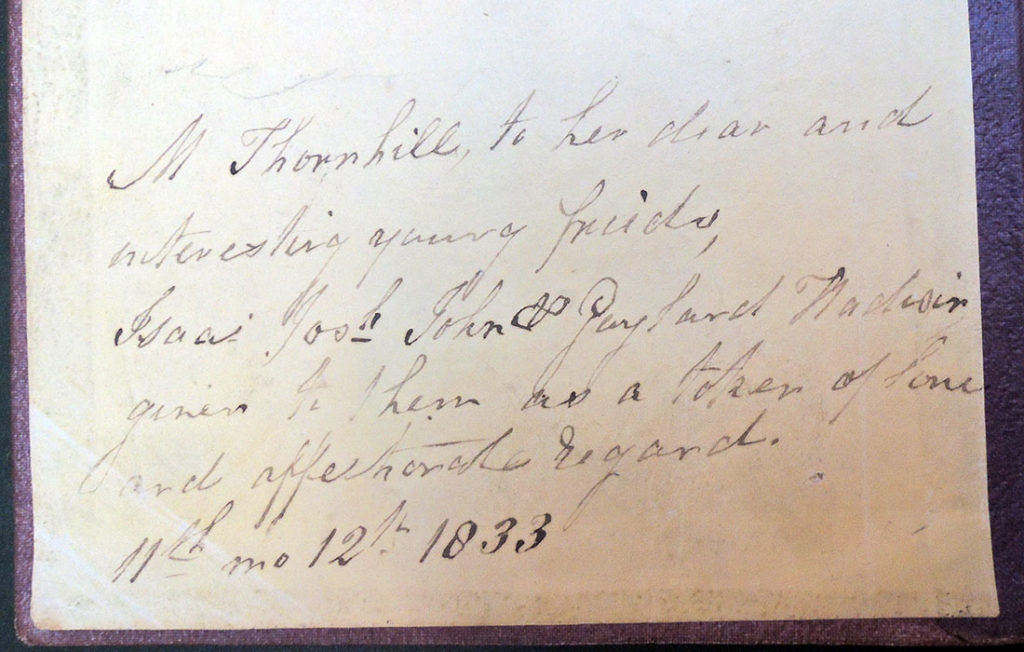

According to OCLC, there are less than a dozen copies of this Benjamin Franklin broadside in the United States and three of them are at Princeton. Folded into a stamped binding (see below), the undated broadside was published after 1790 (Franklin’s death) at the shop of Carington Bowles (1724-1793). Its twenty-five engraved oval vignettes (including a central Franklin portrait) were designed by Robert Dighton (1752-1814) to illustrate Franklin’s maxims.

According to OCLC, there are less than a dozen copies of this Benjamin Franklin broadside in the United States and three of them are at Princeton. Folded into a stamped binding (see below), the undated broadside was published after 1790 (Franklin’s death) at the shop of Carington Bowles (1724-1793). Its twenty-five engraved oval vignettes (including a central Franklin portrait) were designed by Robert Dighton (1752-1814) to illustrate Franklin’s maxims.

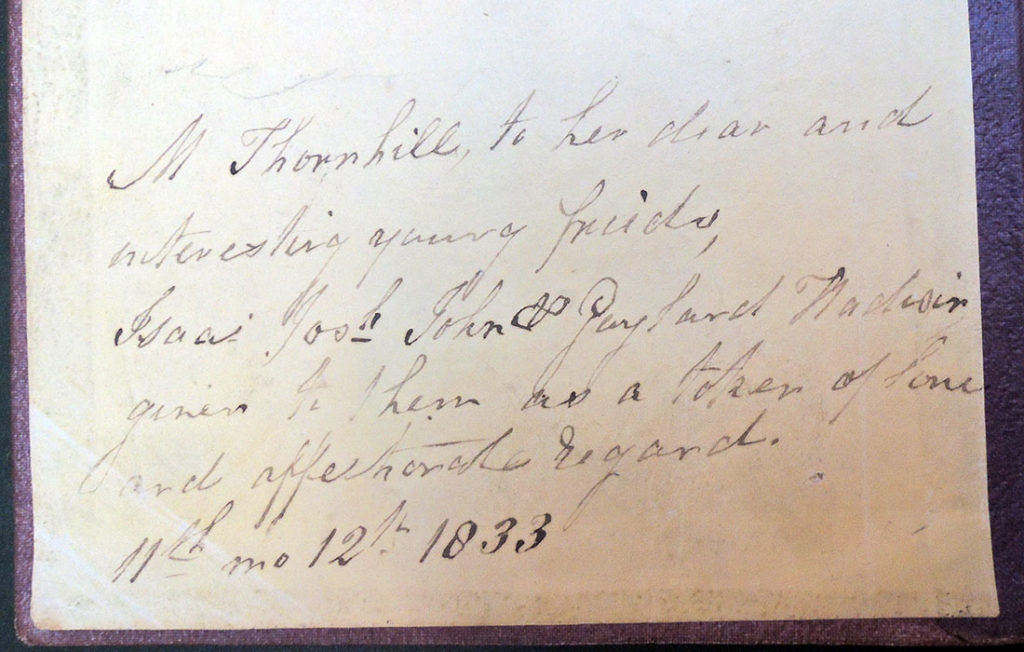

Benjamin Franklin (1706-1790), Bowles’s Moral Pictures, or, Poor Richard illustrated: Being Lessons for the Young and the Old on Industry, Temperance, Frugality &c. By the Late Dr. Benj. Franklin (Manchester (Exchange St. and St. Anns Square): Bancks & Co., [between 1819 and 1839]). Graphic Arts Collection 2007-0083N

The biography for Robert Dighton (1752-1814) posted by the British Museum lists his shop at 12 Charing Cross; 6 Charing Cross; and 4 Spring Gardens Charing Cross, London. “A singer and draughtsman, especially known for designs for satirical prints, which he initially supplied to Carington Bowles and Haines. Later plates he etched, published and sold himself. Stole prints from the British Museum (see A. Griffiths, ‘Landmarks in Print Collecting’, BM 1996, pp. 10, 49-50, 60, 276-83). Son of the art dealer, John Dighton (q.v.). Father of three artists, Robert junior, Denis and Richard (q.v.), who seem to have worked together as a family business, with a common stock of plates.”–Britishmuseum.org

This broadside evolved through a long series of publications. Here at Princeton, we hold:

1747

Benjamin Franklin (1706-1790), Poor Richard improved: being an almanack and ephemeris … for the bissextile year, 1748. : … Fitted to the latitude of forty degrees, and a meridian of near five hours from London; but may, without sensible error, serve all the northern colonies by Richard Saunders, philom (Philadelphia: printed and sold by B. Franklin, [1747]). “Richard Saunders” is a pseudonym. Probably calculated by Theophilus Grew. An advertisement for his school of mathematics appears on p. [30]. William H. Scheide Library 102.48

1748

Benjamin Franklin (1706-1790), Poor Richard improved: being an almanack and ephemeris … for the year of our Lord 1749: … Fitted to the latitude of forty degrees, and a meridian of near five hours west from London : but may, without sensible error, serve all the northern colonies by Richard Saunders, philom. (Philadelphia: Printed and sold by B. Franklin, and D. Hall, [1748]). “This is the first Poor Richard almanac to contain the woodcuts showing the occupations of the months,” Cf. Hamilton. Sinclair Hamilton Collection Hamilton 27

1757

Benjamin Franklin (1706-1790), Poor Richard improved; being an almanack and ephemeris … for the year of our Lord 1758 … by Richard Saunders, philom. (Philadelphia: Franklin and Hall, 1757). This number contains collection of proverbs which were reprinted in England as the Way to wealth. “This is most rare and valuable of the series.” Sabin. According to Ford and Evans this is the last number edited by Franklin. Rare Books (RB) RHT American-81

1779

Benjamin Franklin (1706-1790), The Way to Wealth: as clearly shewn in the preface of an old Pensylvanian [sic] almanack, intitled, Poor Richard, improved. Written by Dr. Benjamin Franklin. Extracted from the Doctor’s political works ([London: printed for J. Johnson, 1779]). Broadside. 31 x 39.5 cm. Rare Books Oversize 3744.91.395f

1795

Benjamin Franklin (1706-1790), The Way to Wealth, or, Poor Richard improved, by Benj. Franklin (Paris: Printed for Ant. Aug. Renouard, 1795). The Way to Wealth was first published in Poor Richard’s almanac for 1758 and separately issued in 1760 under title: Father Abraham’s speech. The present edition includes the French translation of Quétant and L’Écuy, with special t.-p.: La science du Bonhomme Richard, ou Moyen facile de payer les impôts. Par Benj. Franklin. Paris, Ant. Aug. Renourd, 1795. ExKa copy has bookplate of Grenville Kane. Rare Books 3744.91.395.11

Ford, Franklin Bibliography, p. 69, no. 137.

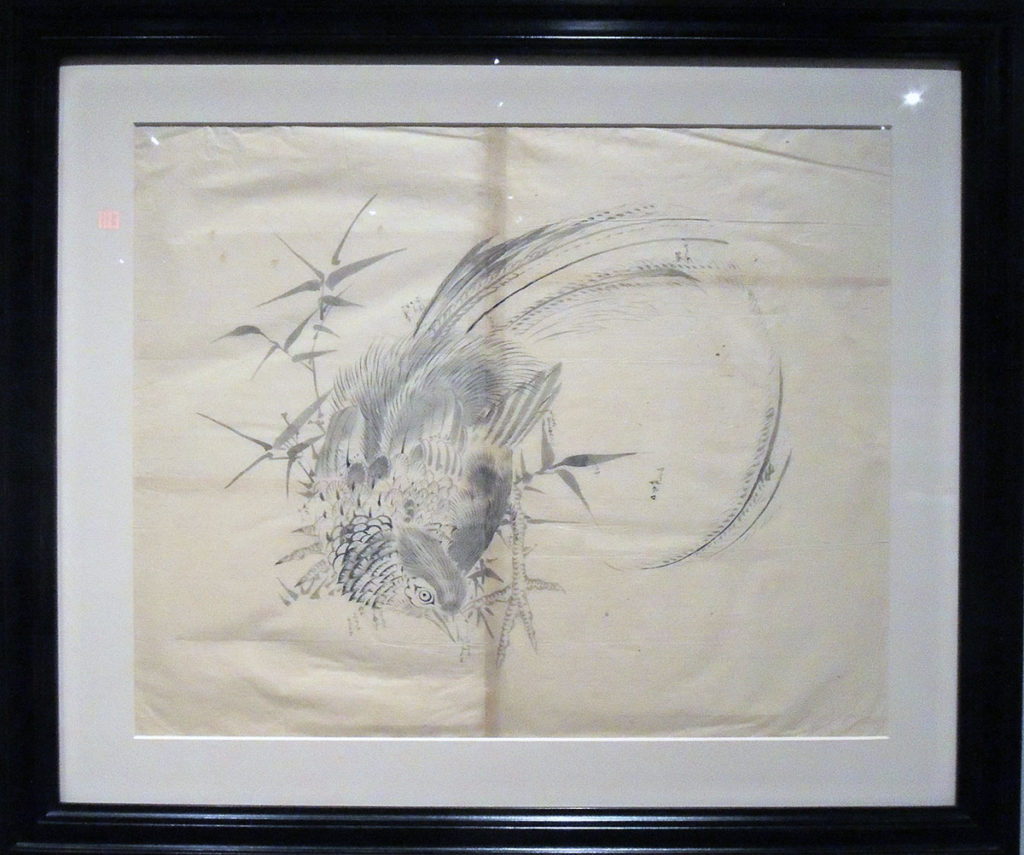

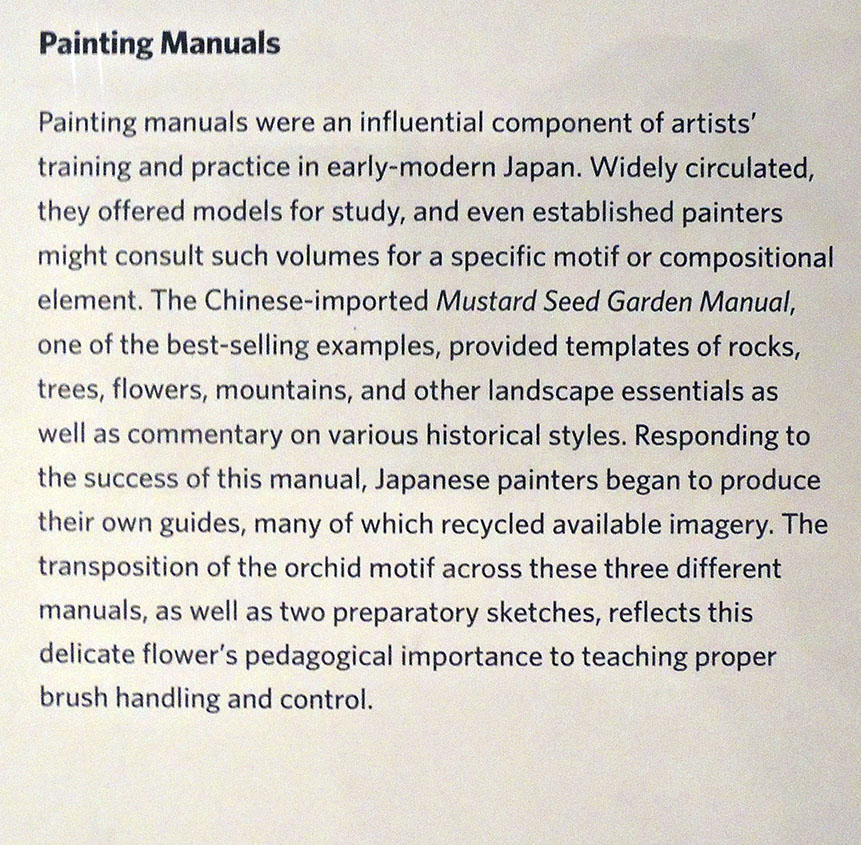

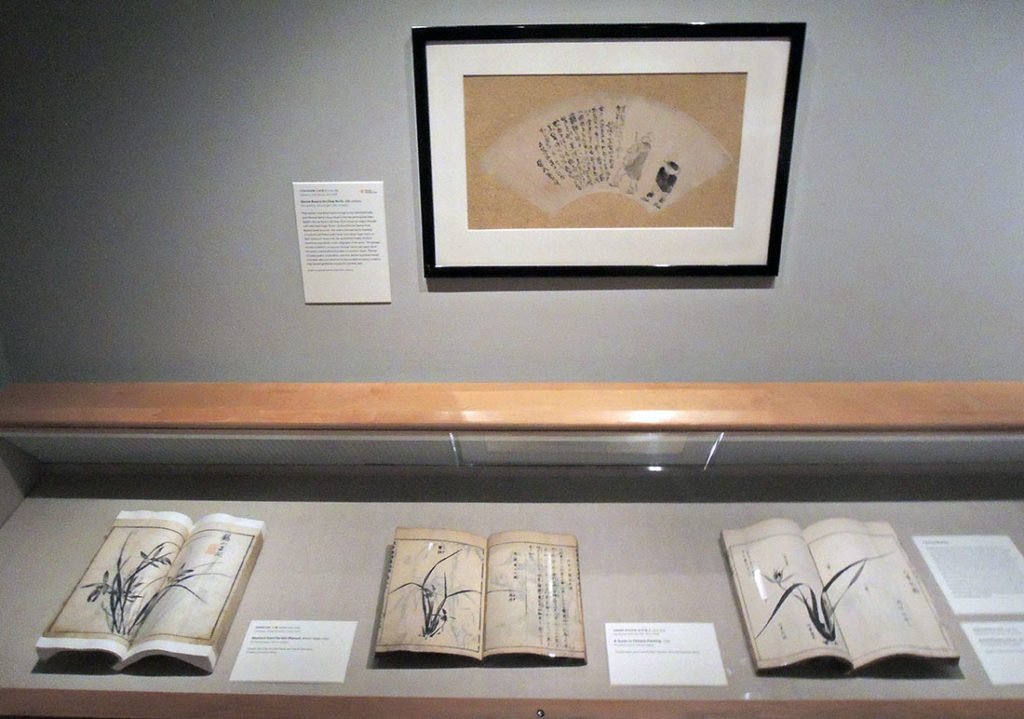

芥子園畫傳 : Jieziyuan Huazhuan : The Mustard Seed Garden Painting Manual. Part one 1679. Woodblock prints. Graphic Arts Collection [far left] https://graphicarts.princeton.edu/2013/12/16/the-mustard-seed-garden-painting-manual/

芥子園畫傳 : Jieziyuan Huazhuan : The Mustard Seed Garden Painting Manual. Part one 1679. Woodblock prints. Graphic Arts Collection [far left] https://graphicarts.princeton.edu/2013/12/16/the-mustard-seed-garden-painting-manual/