Guest post by Martin Heijdra, Director, East Asian Library, Princeton University https://catalog.princeton.edu/catalog/9985474

The following content is largely based upon comparing our images with the list of selected readings at the end of this blog.

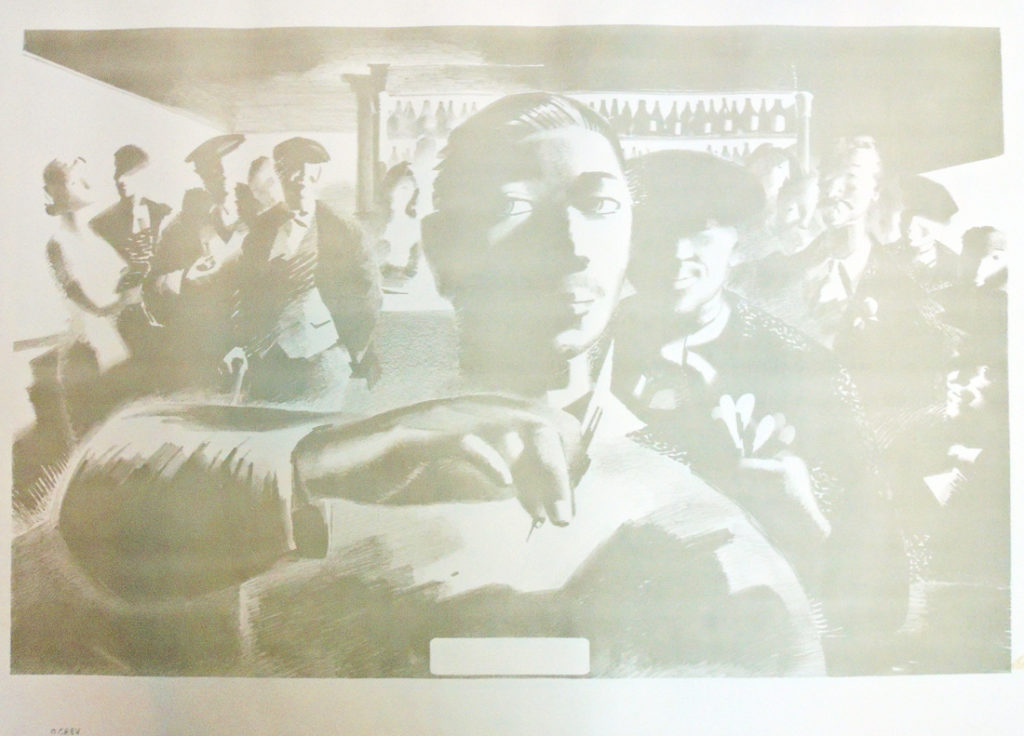

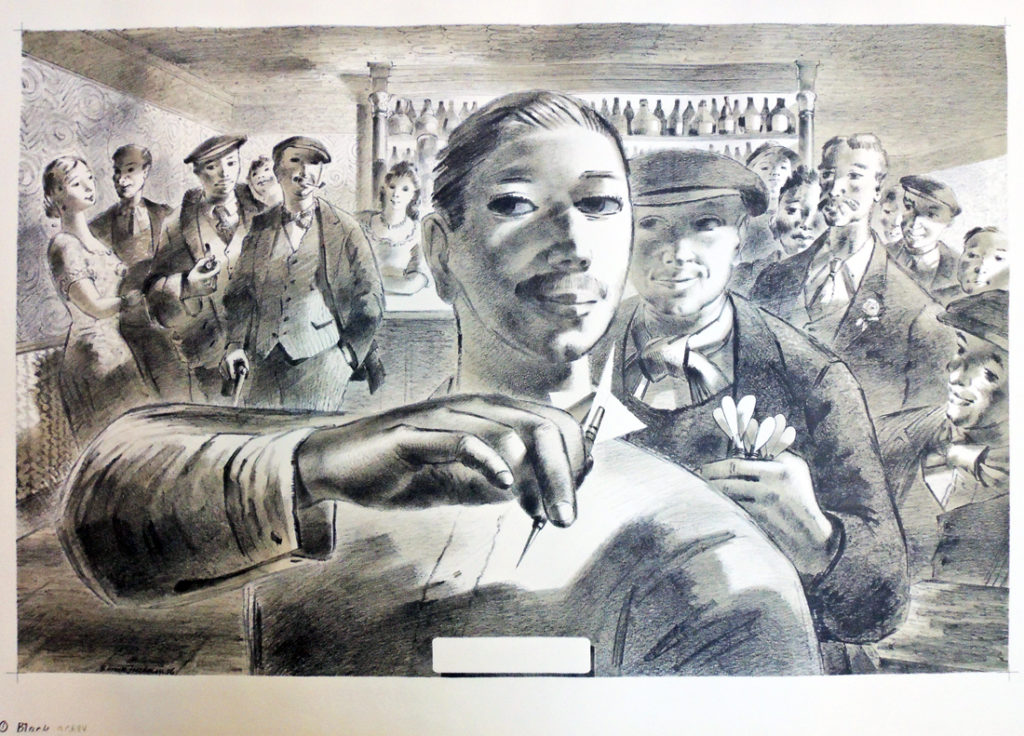

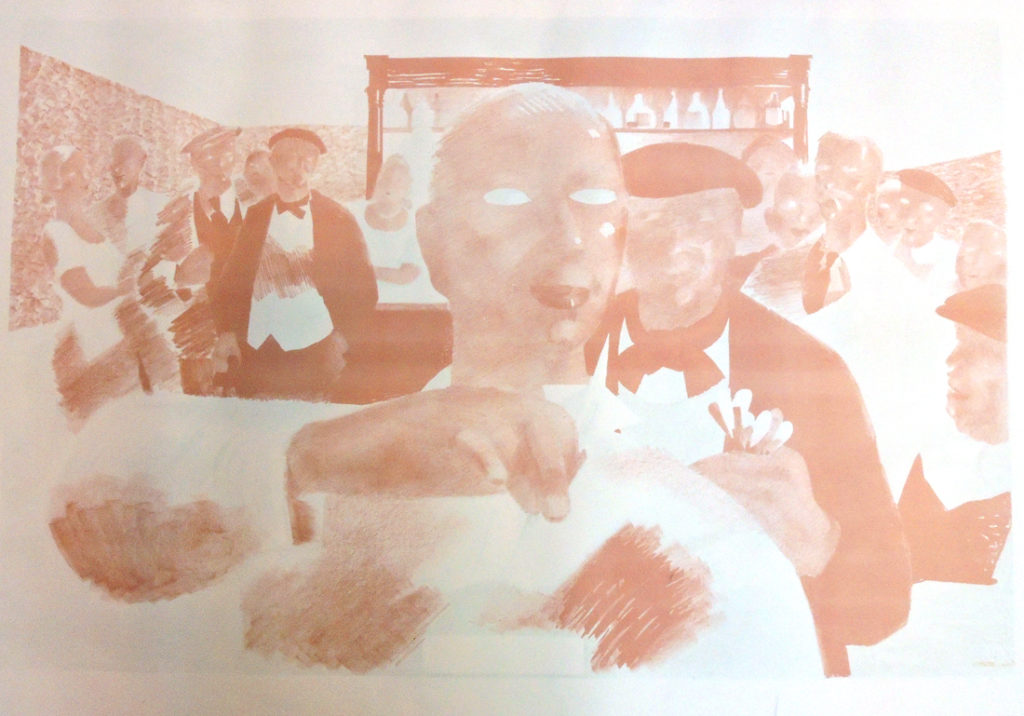

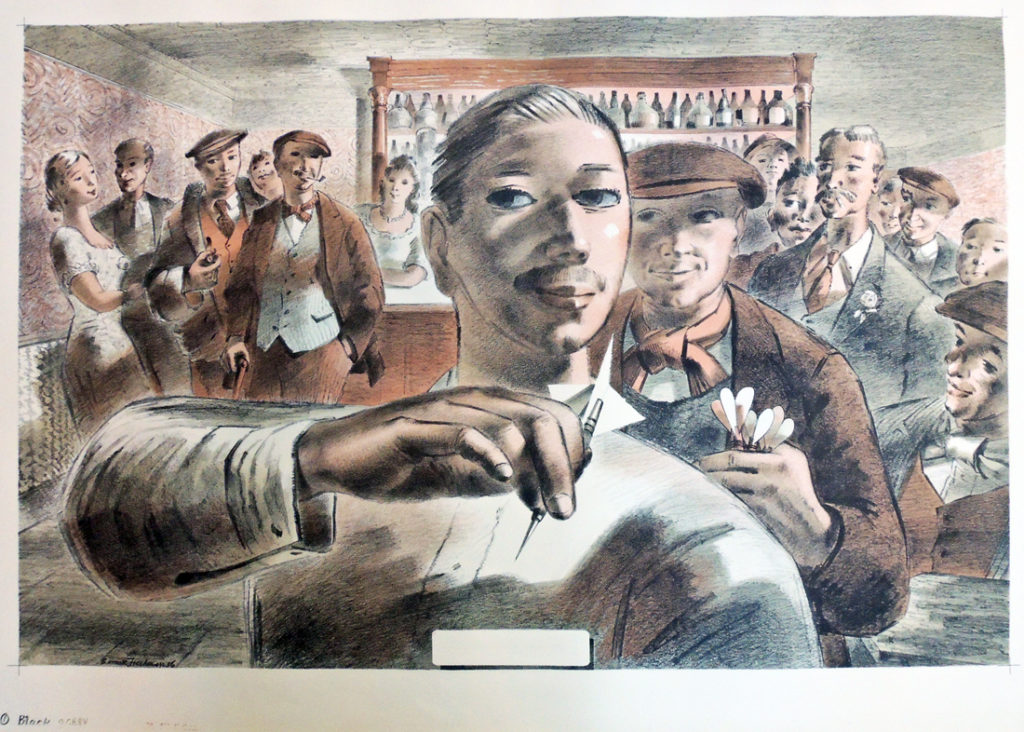

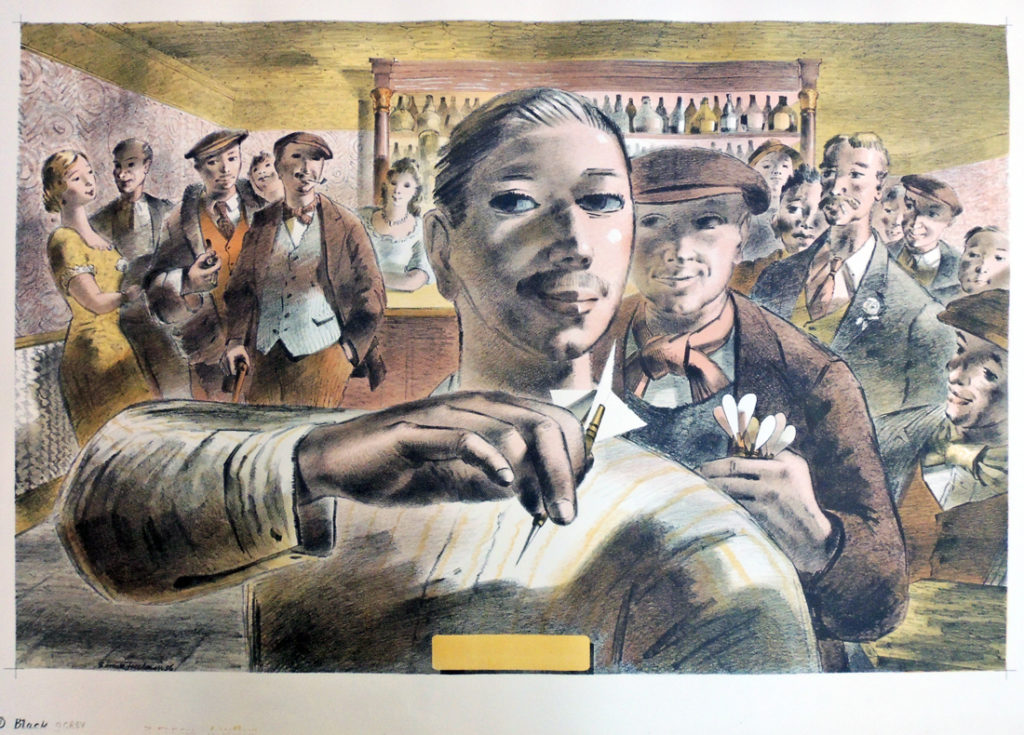

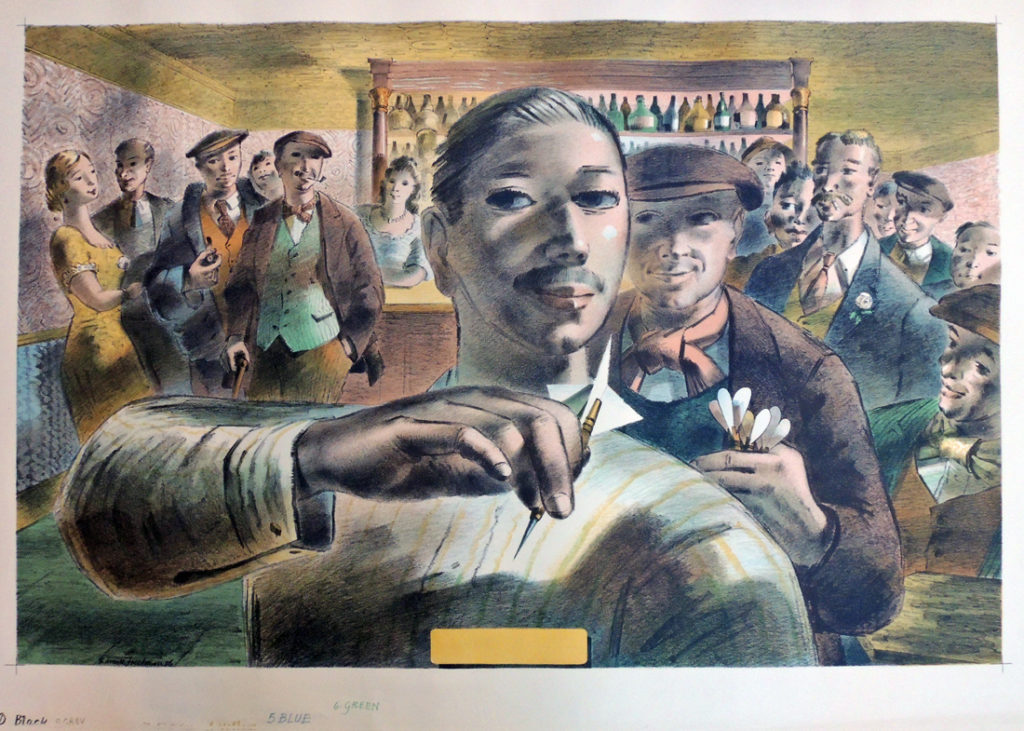

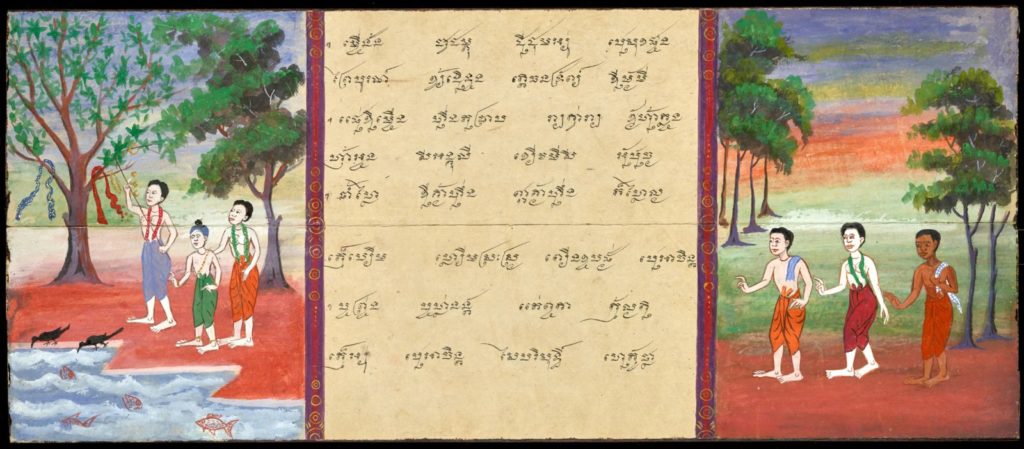

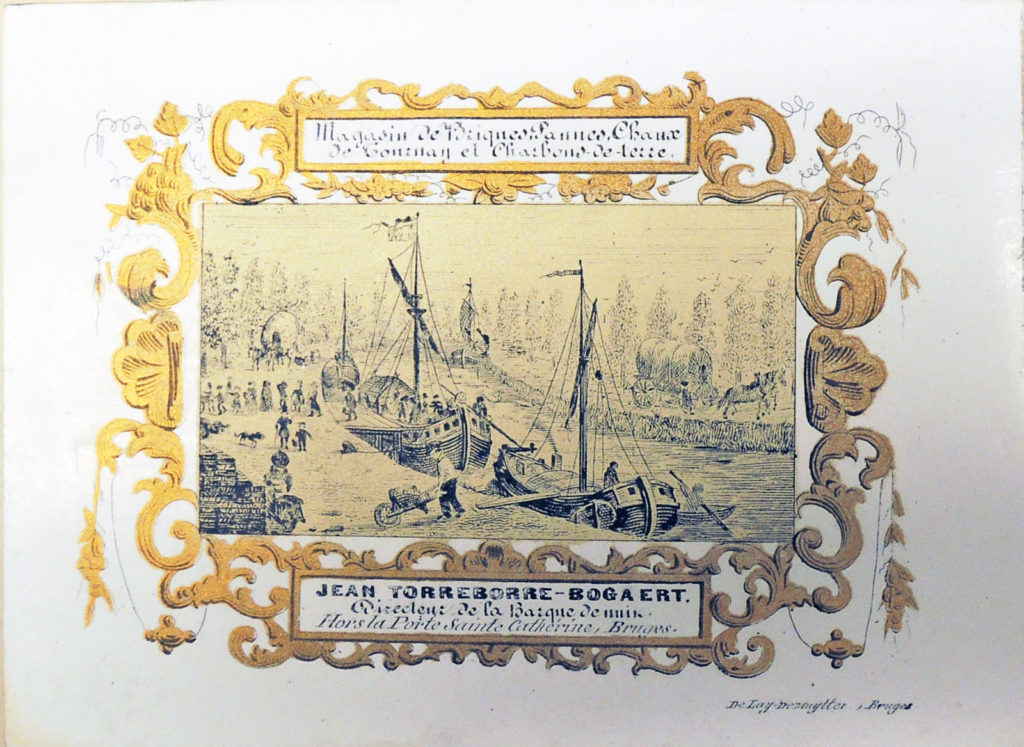

8.

8.

The Legend of Phra Malai is one of the core texts of popular Theravada Buddhist teaching in Southeast Asia, especially in Thailand. The story relates how Phra Malai, a monk who has accumulated great merit, travels to hell, where people ask him to urge their relatives to make merit on their behalf, which indeed he successfully does after having come back to the human realm. When on earth, Phra Malai receives eight flowers from a poor peasant or woodcutter, offered with the hope to not be reborn as a poor man in his next life. To enable that, Phra Malai goes to the Tāvitiṁsa Heaven, where he meets Indra, the King of Gods, in front of the Cūḷāmaṇi Cetiya, a stupa with the relics of the Buddha’s hair.

This stupa was built by Indra in order to give the Deities an opportunity to continue to gain merit. Indra explains to Phra Malai the circumstances in which twelve of these deva deities had gained their merits. Finally Metteyya, the Buddha of the Future (Maitreya) comes from Tusita Heaven, and converses with Phra Malai. Some detailed ways to gain merit are discussed, including listening in one day and night to the Vessantara Jātaka. A deterioration of the world is predicted, to be followed by the final coming of Metteya, beginning a reign of harmony and happiness. On earth, Phra Malai tells this story to his listeners, explain to them the many ways of gaining merit.

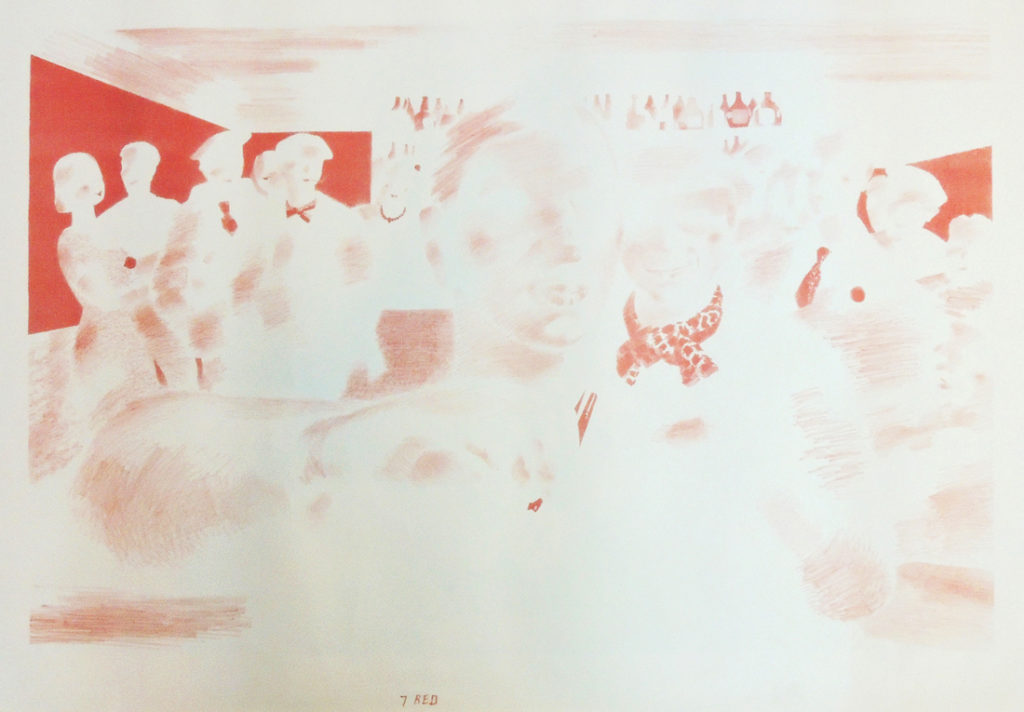

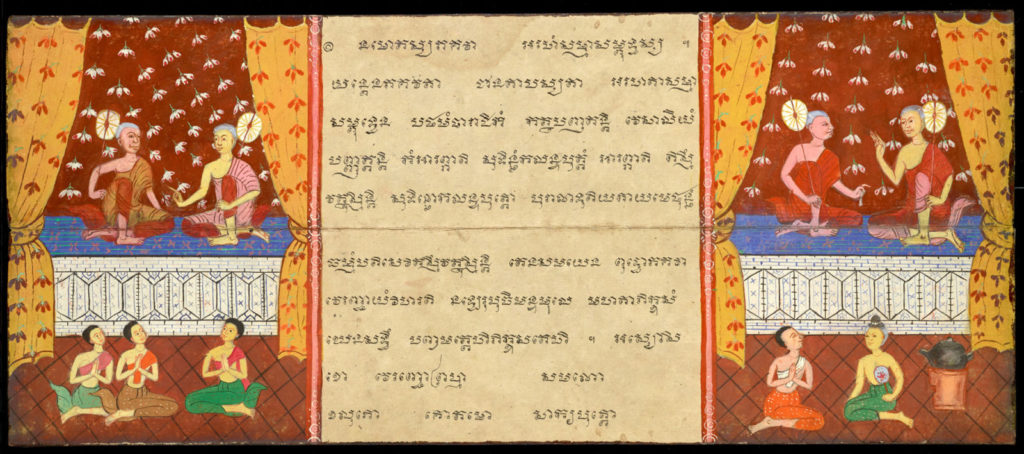

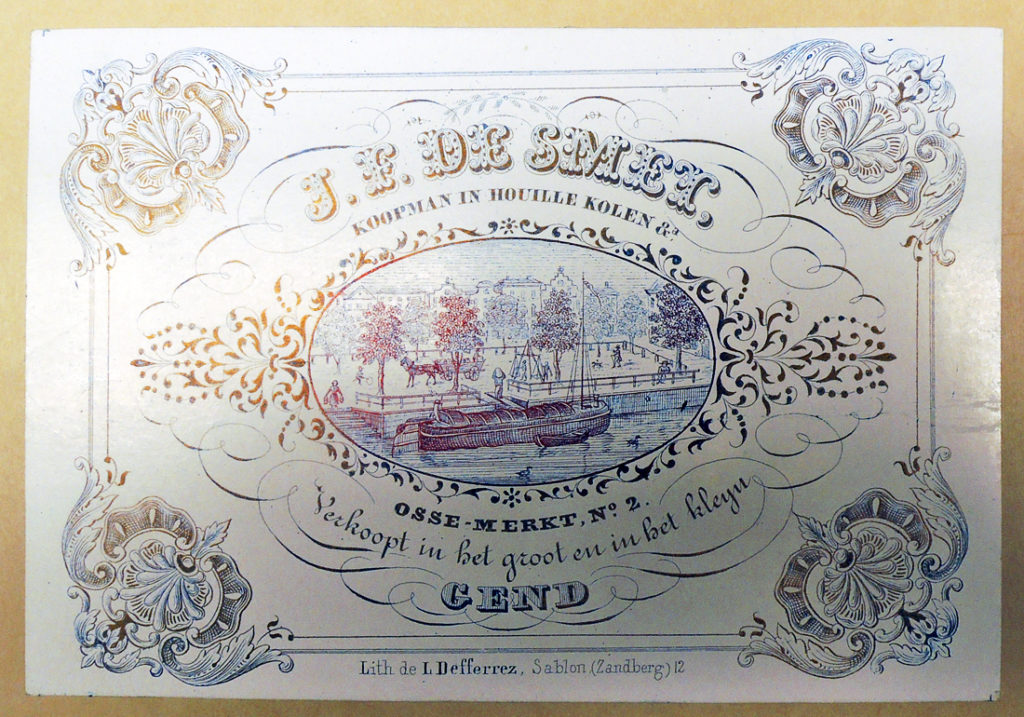

24.

24.

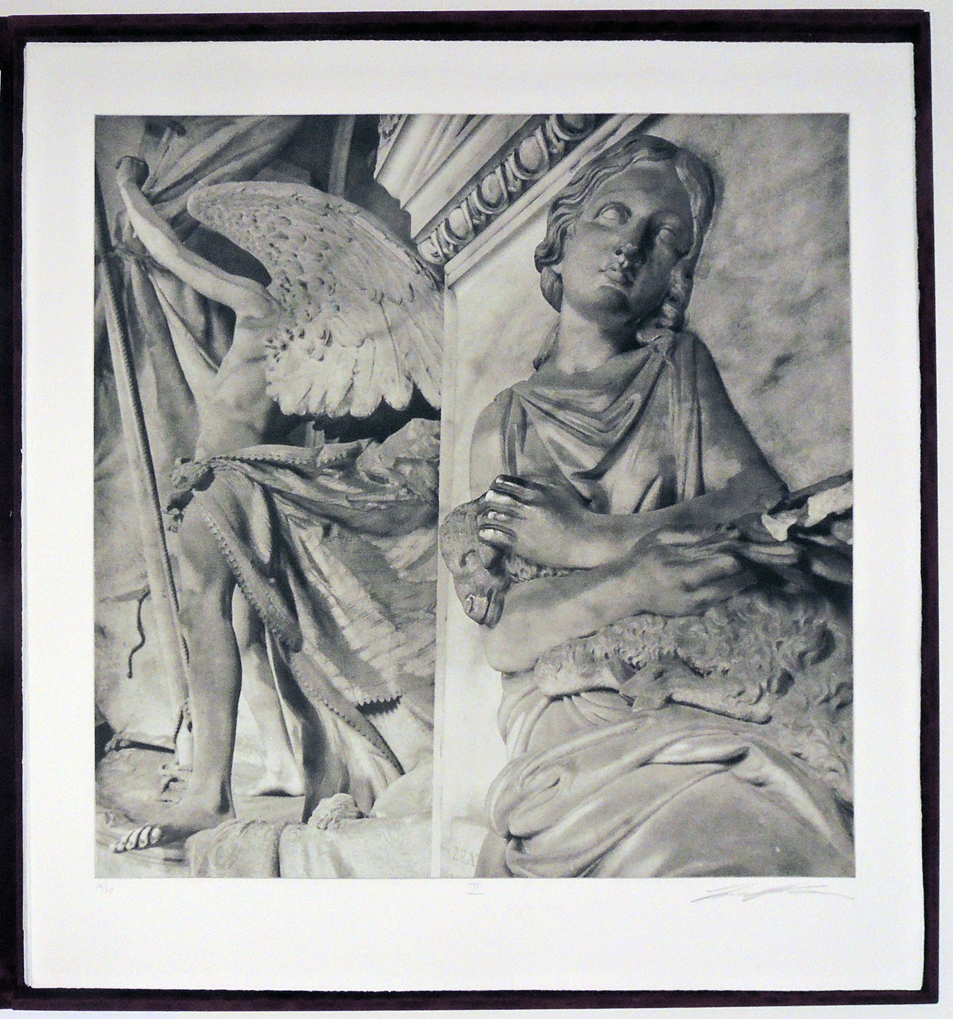

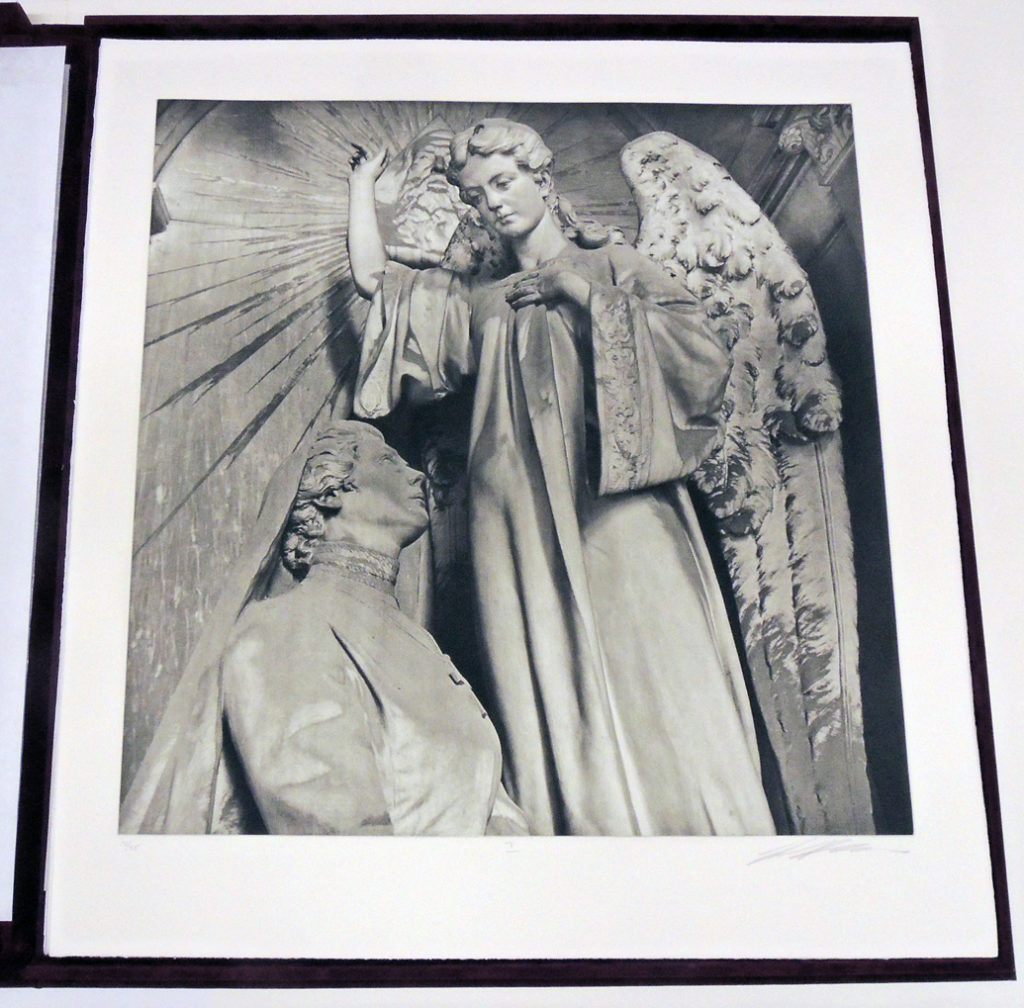

85.

85.

There are several traditions of this legend, from popular to elitist. Ours belongs to the popular Phra Mālai klō̜n sūat พระมาลัยกลอนสวด tradition: illustrated texts written on accordion-folded samut khoi paper manuscripts using Khmer script, but in the Thai language (and incorporating Thai tone marks in the Khmer script). These are recited, sung and dramatized for an unsophisticated audience, with colloquial, sensational, even bawdy texts. The earliest extant version dates to the first half of the 18th century, although earlier versions most likely existed.

Samut khoi books (samut: book, khoi: a kind of tree: Streblus asper, or Trophis aspera) are made of boiled khoi bark: the resulting paste, of a naturally off-white color, is dried on cloth frames, and when ready, inscribed on both sides with black ink (or the paper is blackened with lampblack and inscribed with white or colored chalk/ink.). Recitation sessions (and texts) start after a brief chanting of Pali scripture (usually seven books of the Abhidhamma, i.e. the Basket of Higher Doctrine, the last of the three constituting parts of the Pali Canon which contains a detailed scholastic analysis and summary of the Buddha’s teachings.), before the actual Phra Malai legend begins.

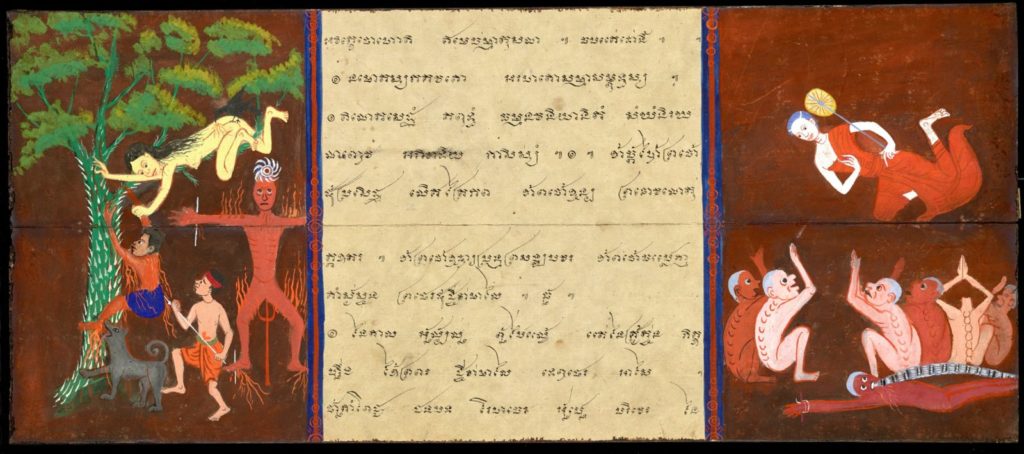

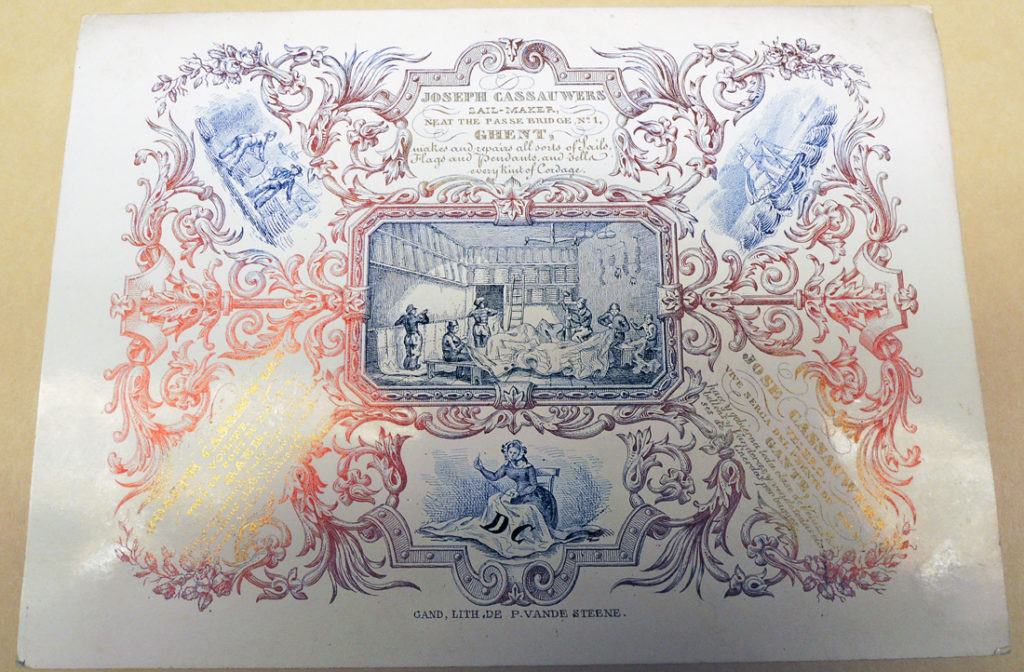

69.

69.

The legend is in rather easy Thai, written in the kap poetry style derived from Cambodian, and emphasizes karmic retribution for sins and good deeds. The popular versions include greatly expanded parts and illustrations about Phra Malai’s visit to Hell. In addition, Phra Malai Klon Suat manuscripts are also commonly combined with at least images (rarely texts) from the Thotsachāt ทศชาติ (The last ten birth tales of the Buddha), as is our version. Indeed, the last tale of the Thotsachāt, the Vessantara Jātaka, is the tale whose recitation in one day and one night is told to Phra Malai to be one of the best merit-increasing endeavors.

The Thai funerary context originally implied entertainment and an atmosphere of fun. Such screens are often depicted in the first illustration of the manuscripts, although not in ours, where the monks are rather serious. Reactions against that began during the times of Rama I, but proved difficult to enforce. Still, reading the Phra Malai in these contexts suffered a slow decline, and is now rarely performed.

3.

3.

12.

12.

Selected sources:

Brereton, Bonnie Pacala, Thai Tellings of Phra Malai: Texts and Rituals Concerning a Popular Buddhist Saint, Tempe: Arizona State University, Program for Southeast Asian Studies, 1995.

Brereton, Bonnie Pacala, “Those strange-looking monks in Phra Malai manuscript paintings: Voices of the text,” paper for the 13th International Conference on Thai studies: Globalized Thailand? Connectivity, conflict and conundrums of Thai Studies, 15-18 July 2017, Chiang Mai, Thailand, pp. 68-75

Ginsburg, Henry, Thai Art and Culture: Historic Manuscripts from Western Collections, Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2000

Ginsburg, Henry, Thai Manuscript Painting, Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1989.

Igunma, Jana, “A Buddhist monk’s journey to heaven and hell,” Journal of International Association of Buddhist Universities 3 (2012), pp. 65-62

Peltier, Anatole, “Iconographie de la légende de Braḥ Mālay,“ Bulletin de l’École Française d’Extrême Orient 76 (1982), pp. 63-76

Explanation of the images

Our version of the Phra Malai Klon Suat contains the following illustrations (the numbers refer to those given to the images given in the digitized version, not to the actual folio): https://catalog.princeton.edu/catalog/9985474

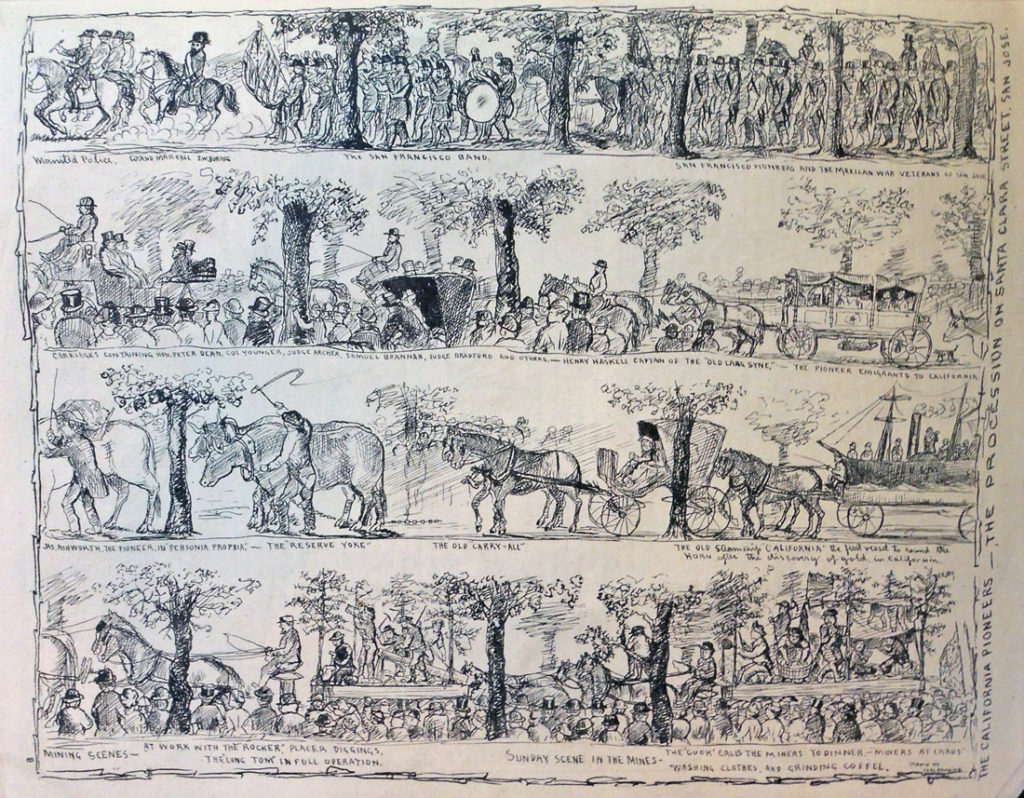

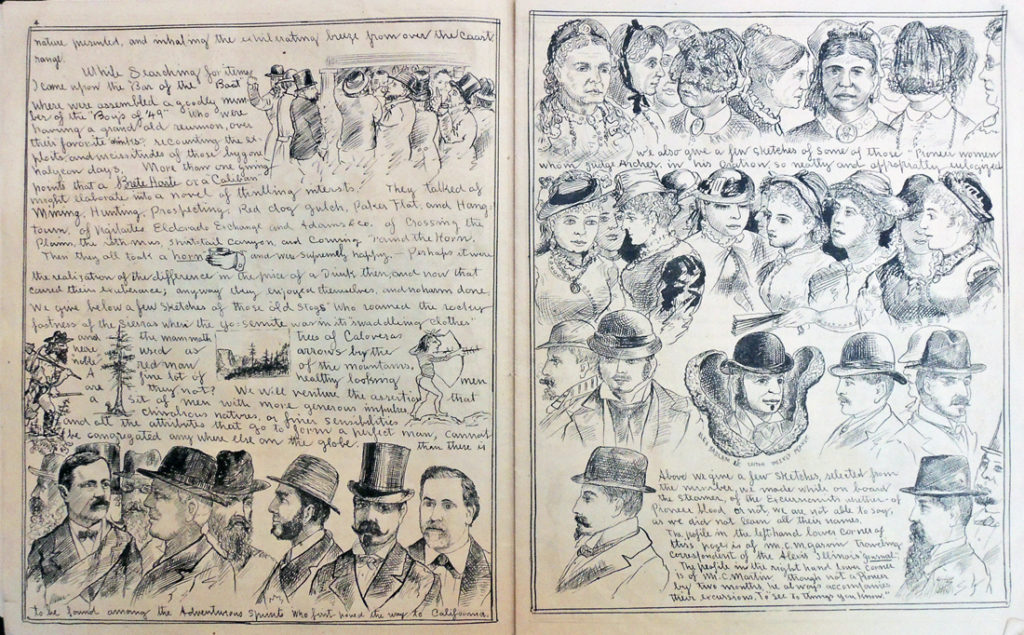

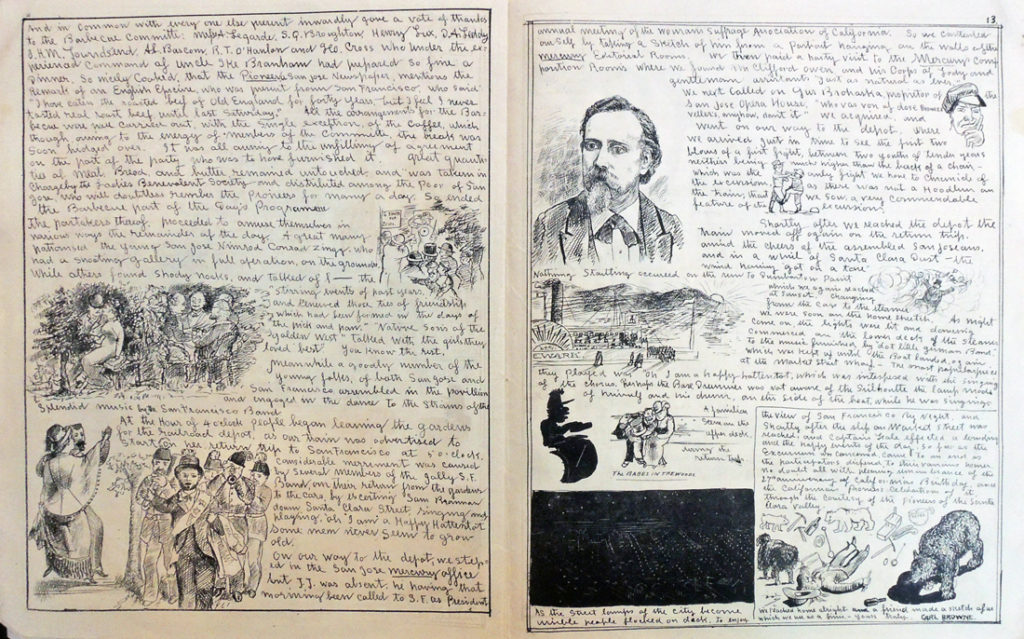

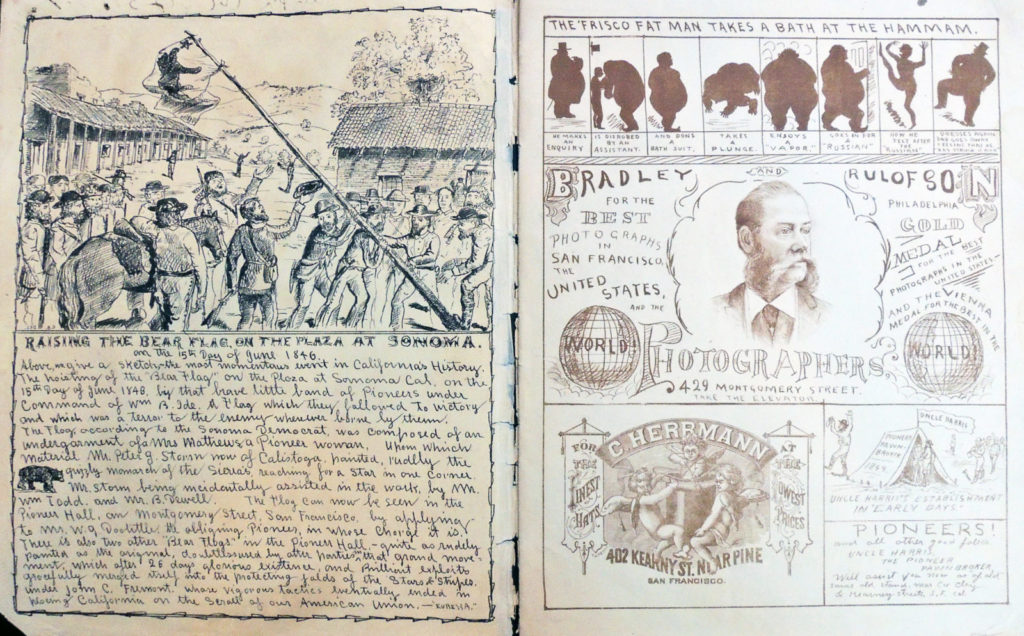

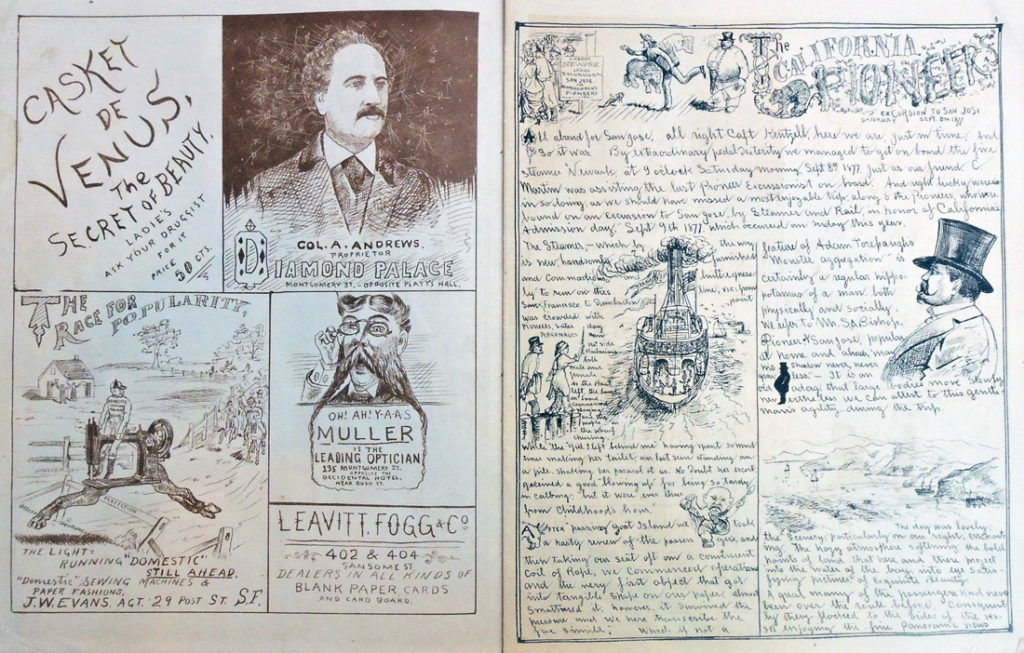

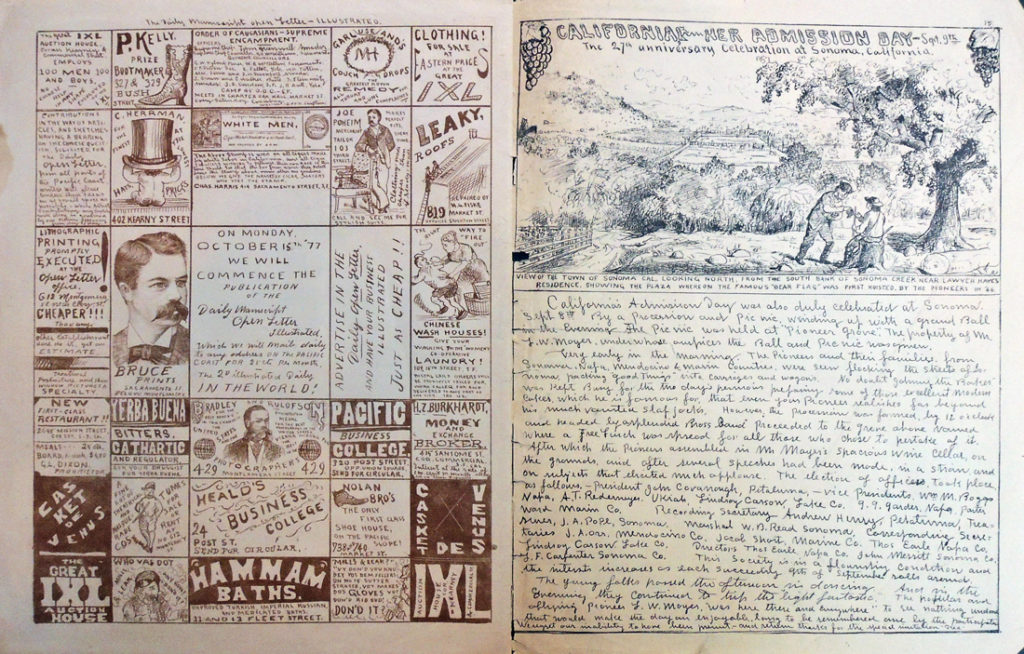

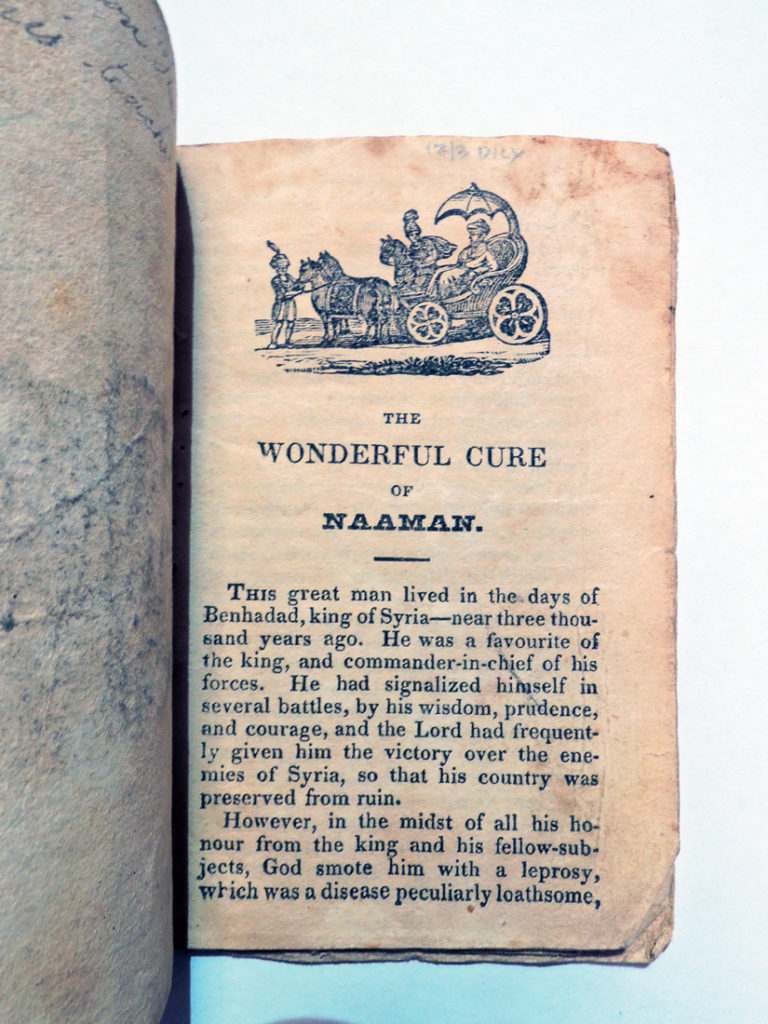

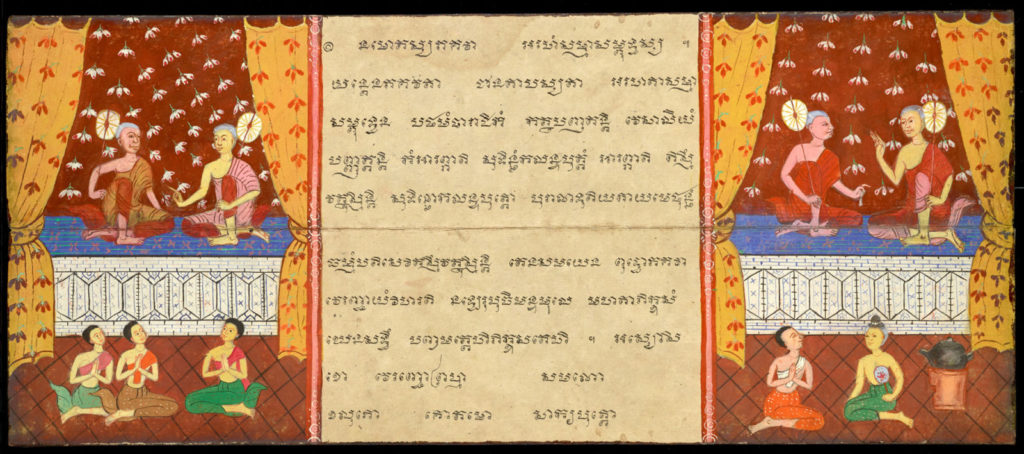

3. This is the usual opening scene of Phra Malai Klon Suat manuscripts, where monks, carrying their talabat fans preside over the funeral wake of a deceased person. Wakes traditionally were an occasion of entertainment, although the 19th century saw a religious movement and laws against that practice. In fact, both the monks and the attendees are here, in comparison with other manuscripts, rather demure. The Phra Malai manuscript would be read during such funeral wake, making this a self-referential image.

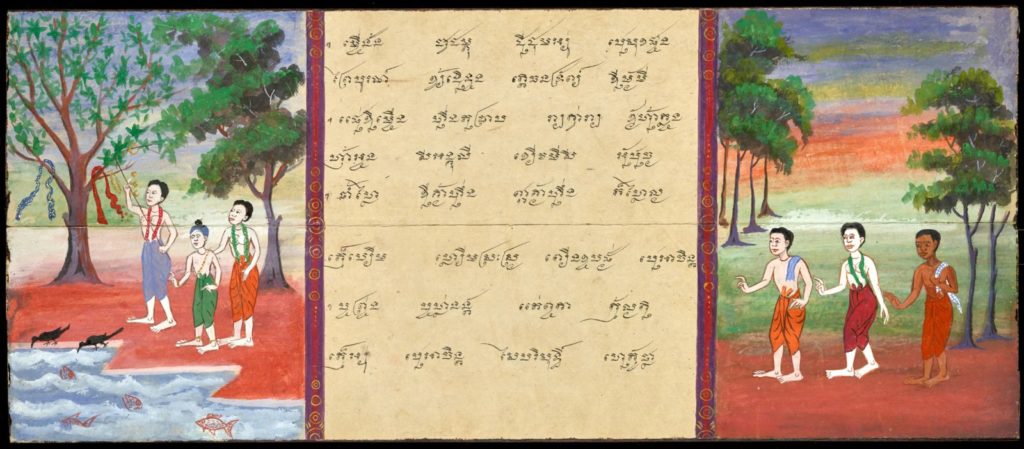

5. This manuscript contains also images from the Thotsachāt (The Ten Birth Tales of the Buddha) and Pali extracts from the Buddhist canon, before the actual Thai Phra Malai Klon Suat starts. These images refer to the third tale. Sama, the future Buddha, looks after his blind parents living as ascetics in the forest. The misguided demon king Piliyakkha shoots Sama when fetching water for his parent, attended by two deer. Thanks to his and his parents’ great merit, Sama comes back to life, and his parents regain their eyesight.

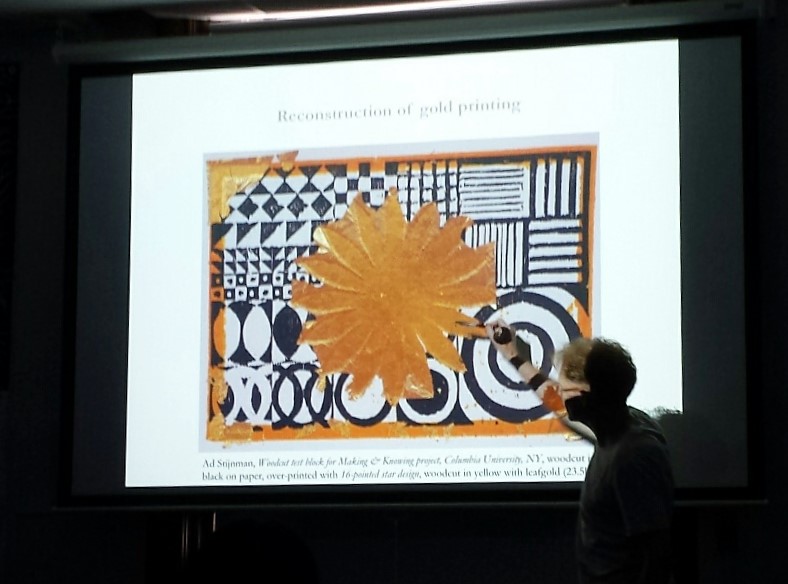

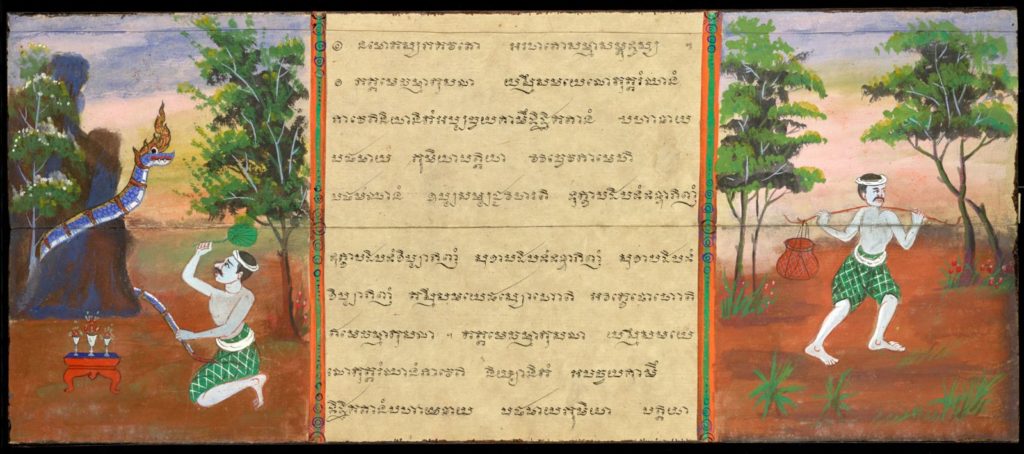

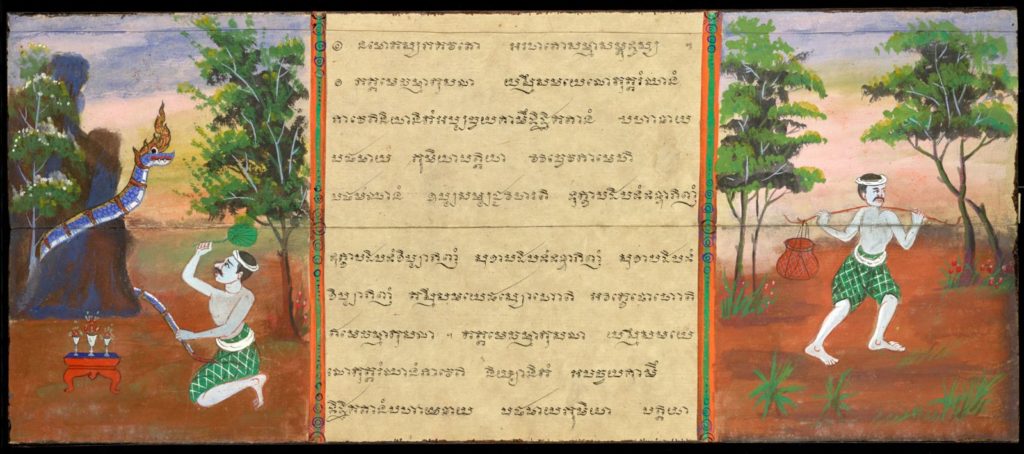

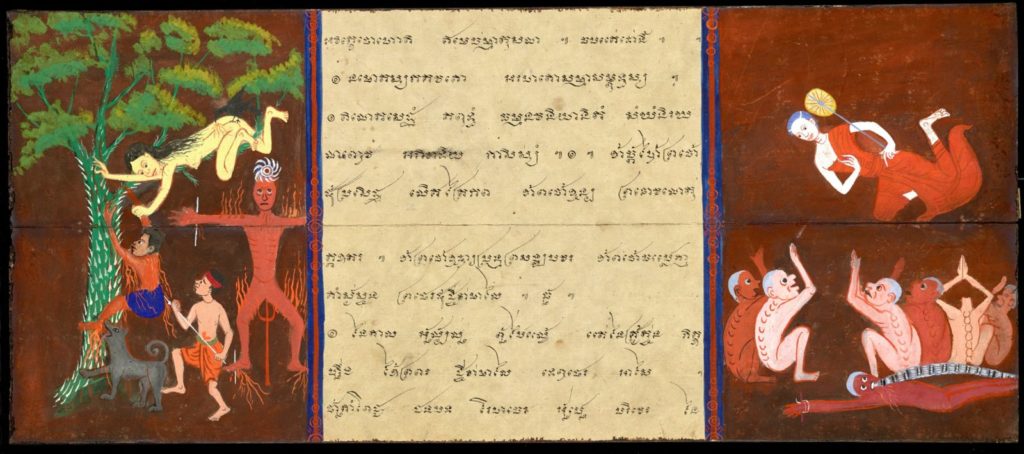

8. In the sixth tale of the Thotsachāt, the future Buddha is a serpent divinity (naga) called Bhuridatta. While coiled around an ant-hill during a fast, he is captured by a vicious hunter who has a spell which can even ensnarl a naga (the spell is hidden in the water he sprinkles on the naga with the branch leaf). The tortured Bhuridatta then is carried to events where has to perform for the hunter, which he does without resentment, ultimately regaining his freedom.

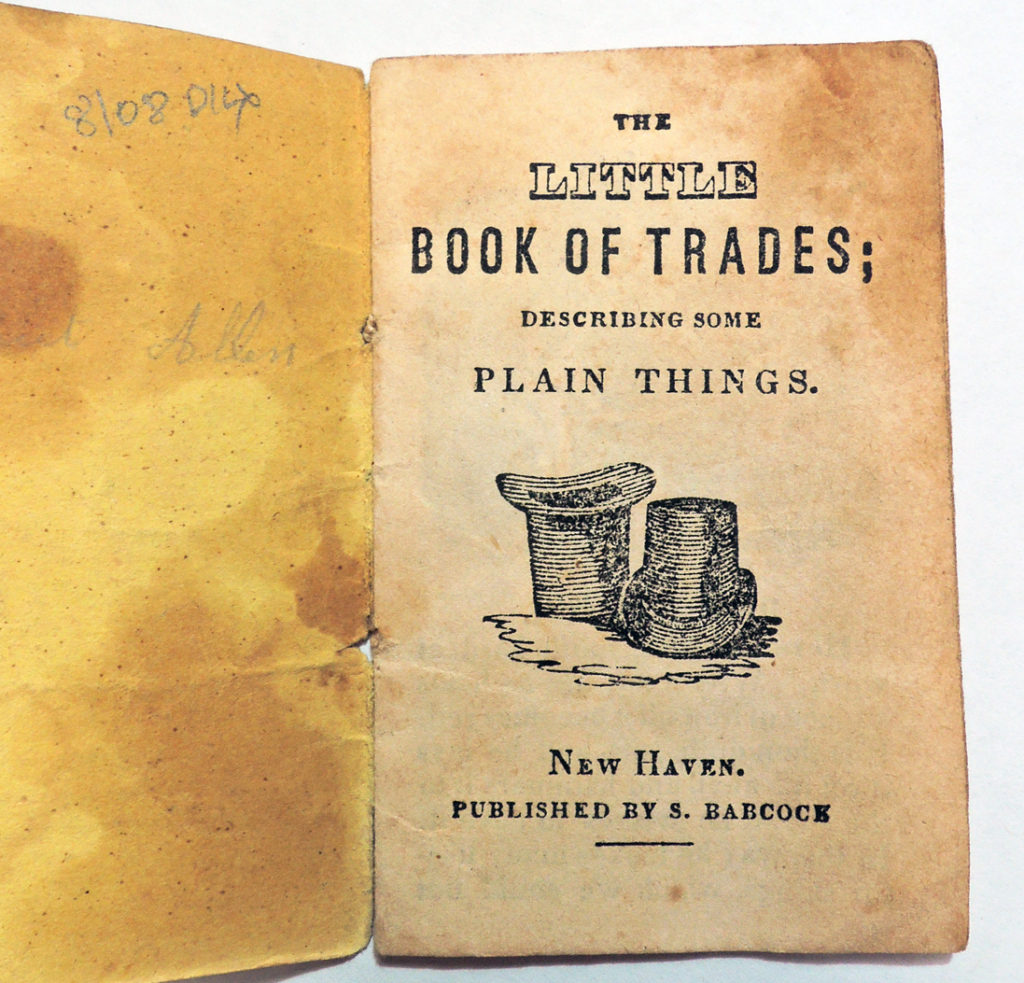

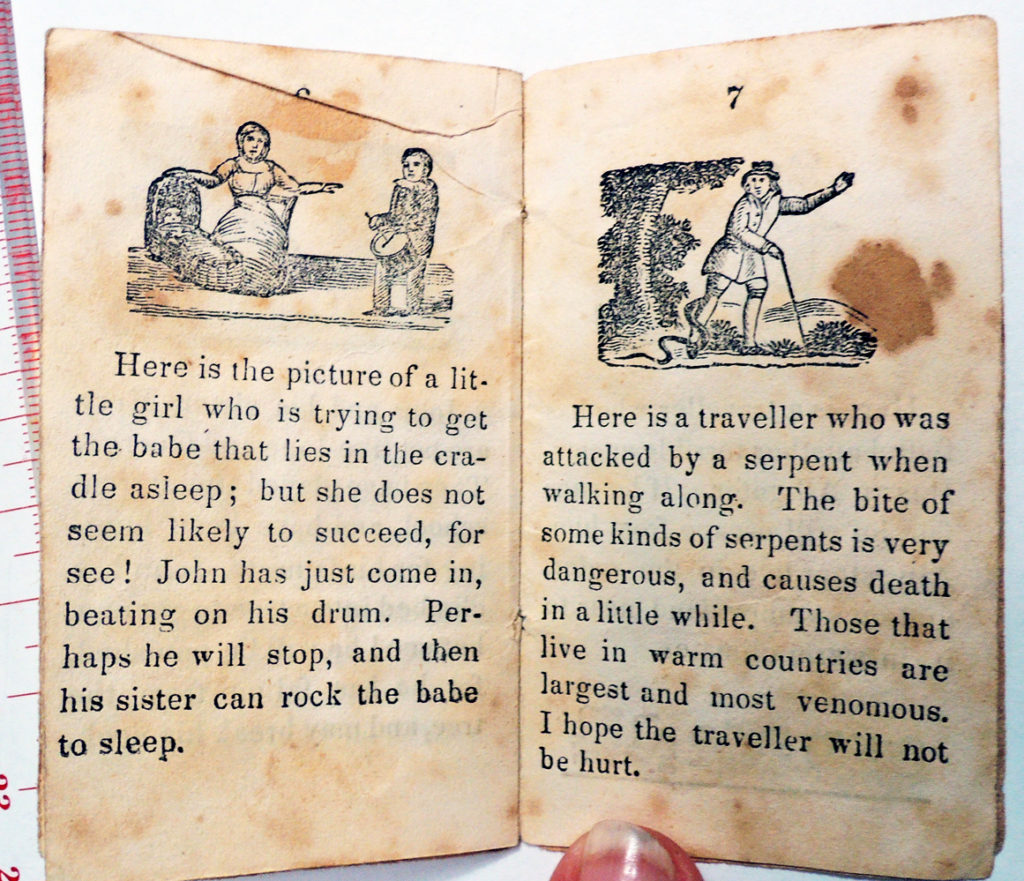

12. These images exemplify the intertwining of the Ten Birth Tales with the Legend of Phra Malai. The left image could come from the fourth birth tale, on King Nimi, who, like Phra Malai, is guided by a divine charioteer through the hells and heavens, as well as the Phra Malai. To the left we see a kapok thorn tree, where adulterers are punished, with the man bitten by a dog and being forced to climb the thorn tree to reach his lover at the top pecked by a vulture. They never meet each other, and the punishment is continuous. To the right we see Phra Malai himself hovering above the denizens of hell. Displayed here are probably those who became intoxicated while on earth, and they have acid or molten copper poured down their throats. Visiting Hell, by his very presence Phra Malai temporarily causes rain to decrease the fire of Hell, allowing the victims to tell their stories. They implore him to make their situation known to their descendants on earth, and create merit on their behalf. The crucifixion shown here and in other similar illustration may be a Western influence of the 19th century—the image above this victim’s head probably derives from a halo, or a crown of thorns; it may also refer to the flying disks which in Hell torture victims’ heads.

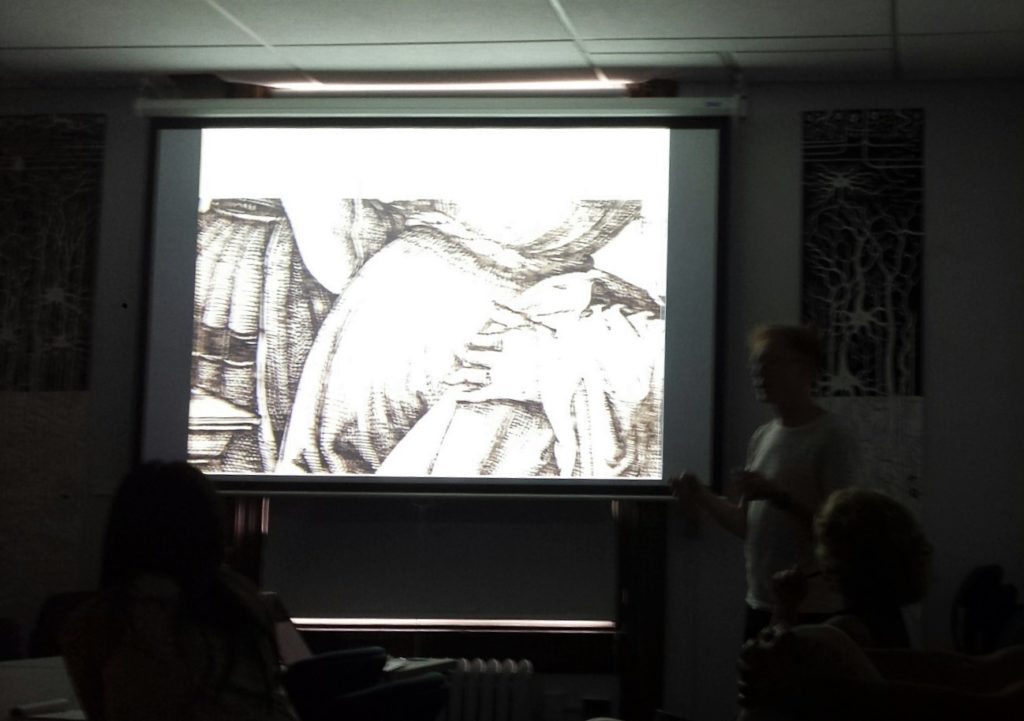

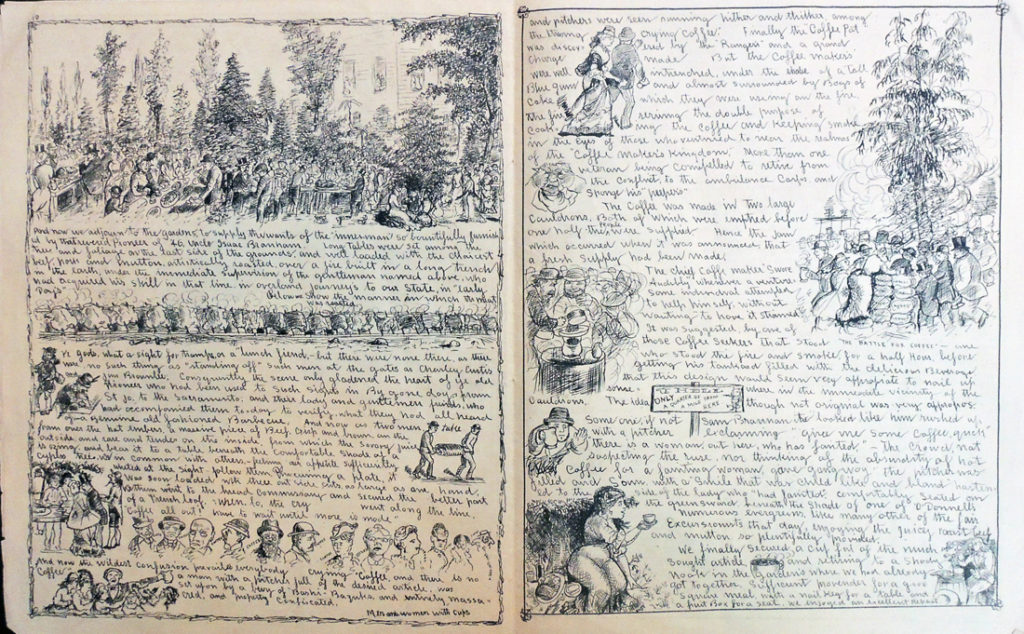

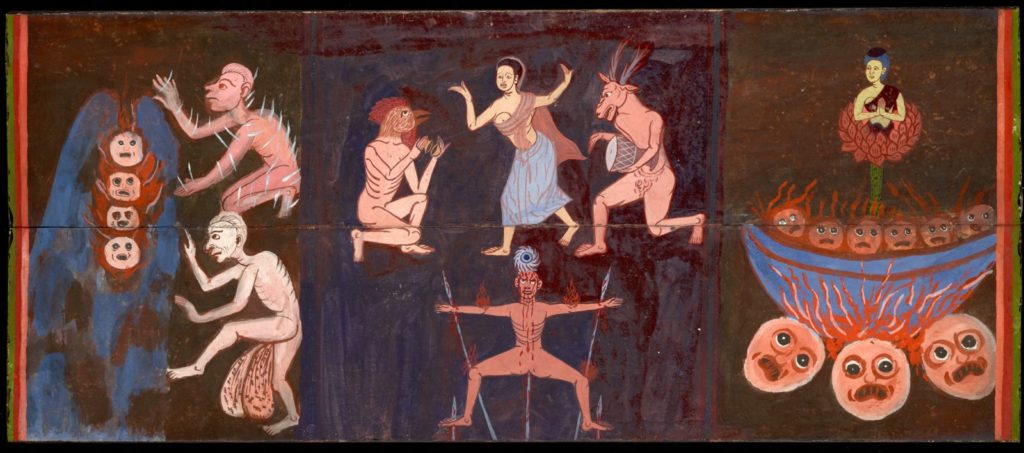

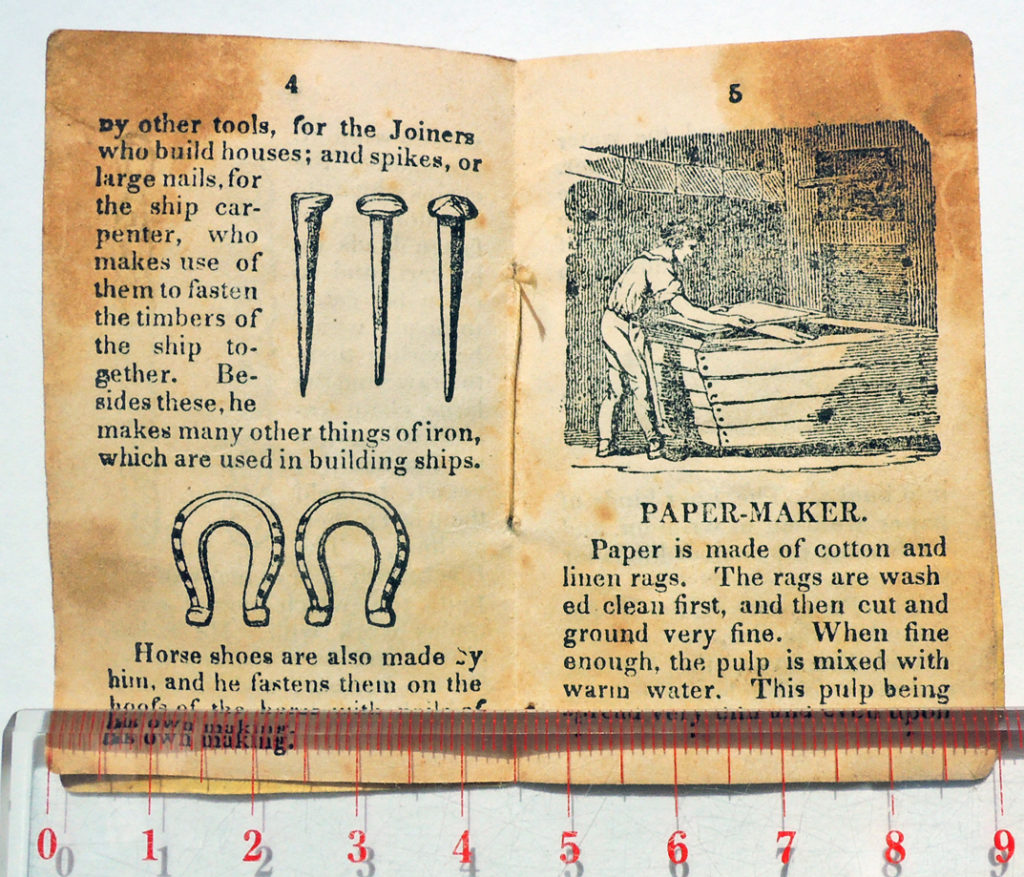

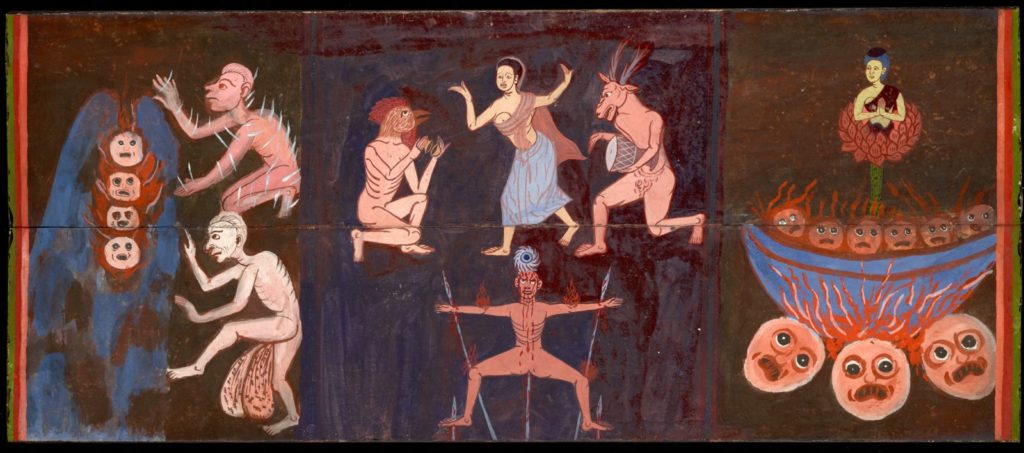

24. This is a full-fledged hell scene, the only image without a central text. Those who butcher pigs for a living or cheat others have their body hairs become sharp swords embedded in their skin (upper left); corrupt rulers are have huge, decayed, foul-smelling testicles hanging down the ground “like a yam shoulder bag” (bottom left); those who abuse their parents or corrupt leaders will have disks cutting of their heads drenched with blood (left?); those abusing monks fall into an iron cauldron in the Lohakumbhi Hell (right, below Phra Malai); those who believe in false spirit mediums are reborn as ghosts that are part animal, part human (top.) The crucified image of the Nimi Tale reoccurs at the bottom, with halo/ crown of thorns/flying disk.

32. A very poor man plucks lotuses and presents them to Phra Malai, with the request that he will never be born poor again. His wish is granted, and Phra Malai will later offer the lotuses in heaven at the Culamani Cetiya. This event is the occasion for painting a landscape scene in these manuscripts. Originally a woodcutter who came to bath, in later versions the poor man became to be described as a poor peasant needing to wash of his sweat after a day of work, with whom the listeners to the story could identify themselves.

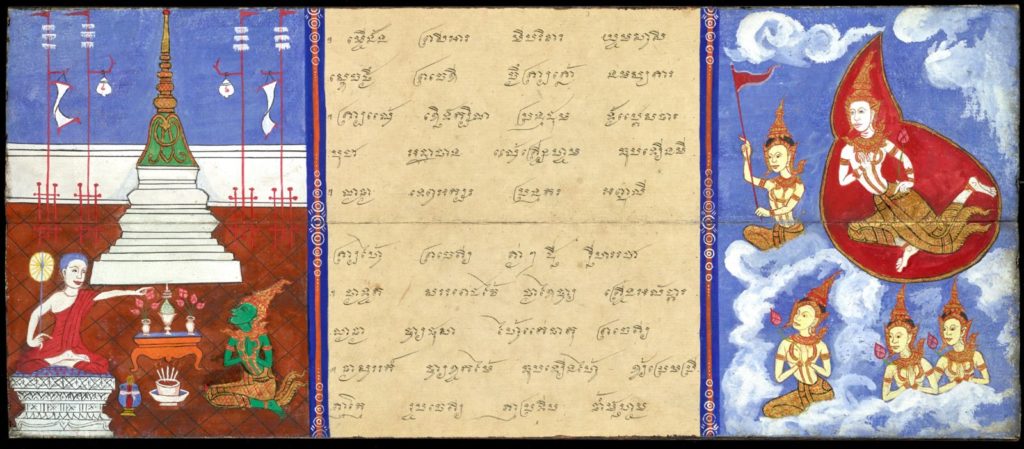

46. Having received the eight lotuses from the poor peasant, Phra Malai immediately goes to the Tavatimsa heaven to offer them to the eight directions of the Culamani Cetiya, a stupa with the relics of Buddha’s hair. He encounters there many deva Great Beings or Deities, one of whom is displayed at the right side, with red halo and exquisitely dressed. Each of these male devas is accompanied by from hundred to tens and tens of thousands of female angels, the number varying according to their merits. These devas all come to pay homage to the Culamani stupa, which was built by Indra, the King of Gods, in order to give also the Deities an opportunity to continue to gain merit. Indra tells Phra Malai the circumstances of how each of these Great Beings accumulated their number of merits.

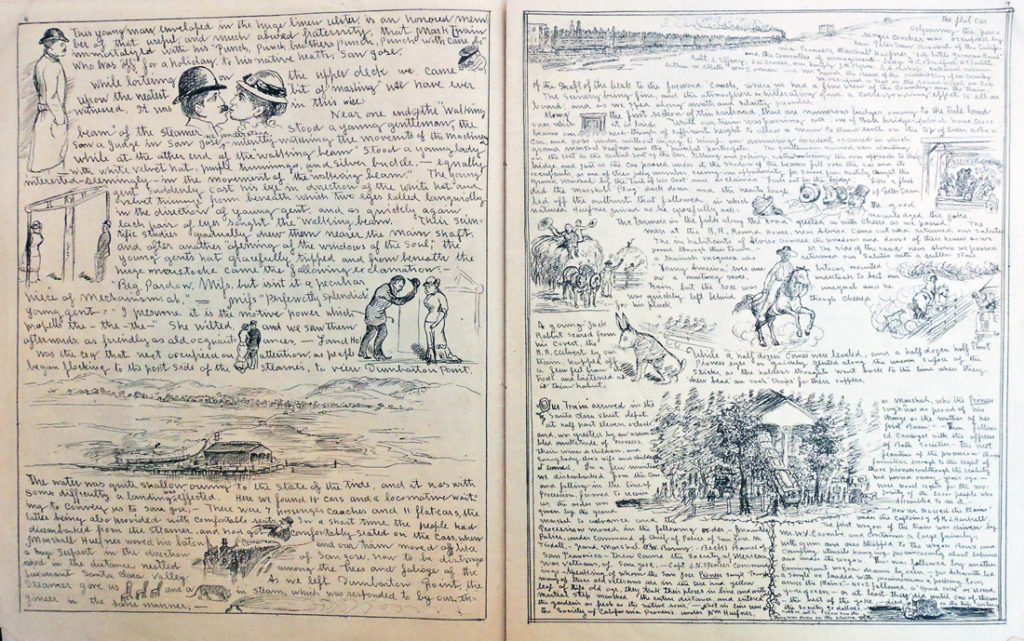

69. Finally the Buddha of the Future (Metteyya, in Sanskrit Maitreya) arrives from his Tusita Heaven. After having paid reverence to the cetiya, he explains to Phra Malai what will happen on earth before he will be reincarnated on earth. First the world will see a strong deterioration of the Buddhist dharma, with people’s life spans becoming increasingly short and incestuous promiscuity in every possible combination reigning everywhere. Most people will die. But after seven days, a new harmonious society will appear, and the earth will flourish. The Metteya will then be born in the human realm and attain enlightenment. These two images are of that harmonious society. All humans who have followed the Buddha’s way of life will be reborn. Huge kalpavriksha wish trees will provide those humans who have fed and clothed monks with whatever goods and valuables they wish for. In the left image a family plucks valuables from such a tree with a pole, while at the right people walk in the predicted harmony, free from worries and sickness. Even the level of water will be just right, “so that a crow can drink just by tilting its head… and so clear that you can see the fish.”

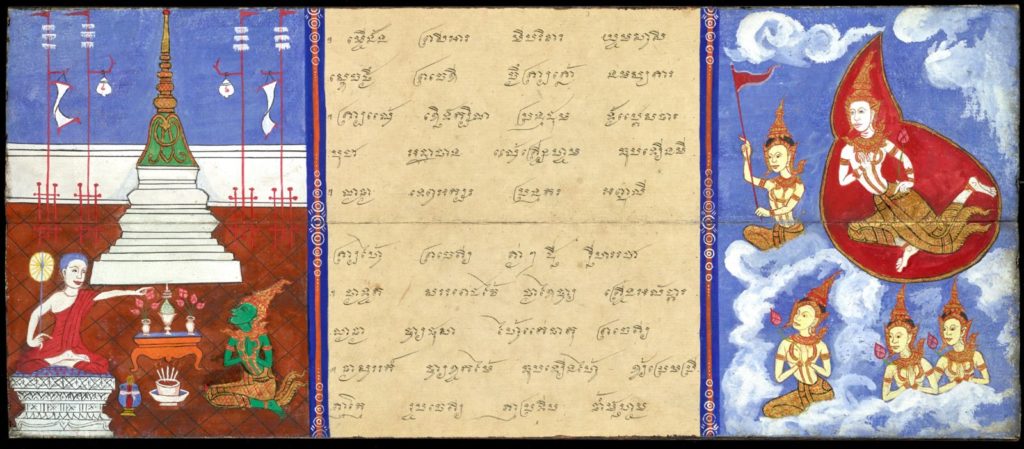

85. These last illustrations usually come earlier. At the left Indra (traditionally in green) is seen conversing with Phra Malai, in front of the Culamani cetiya. To the right the Buddha of the Future, Metteyya, arrives, heralded by his retinue.

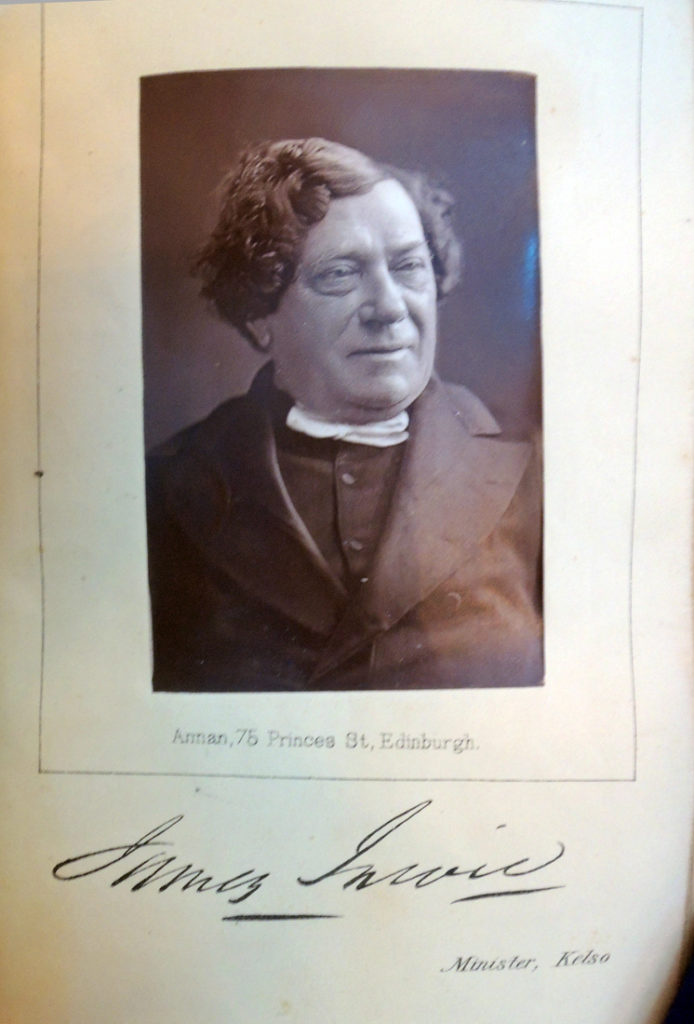

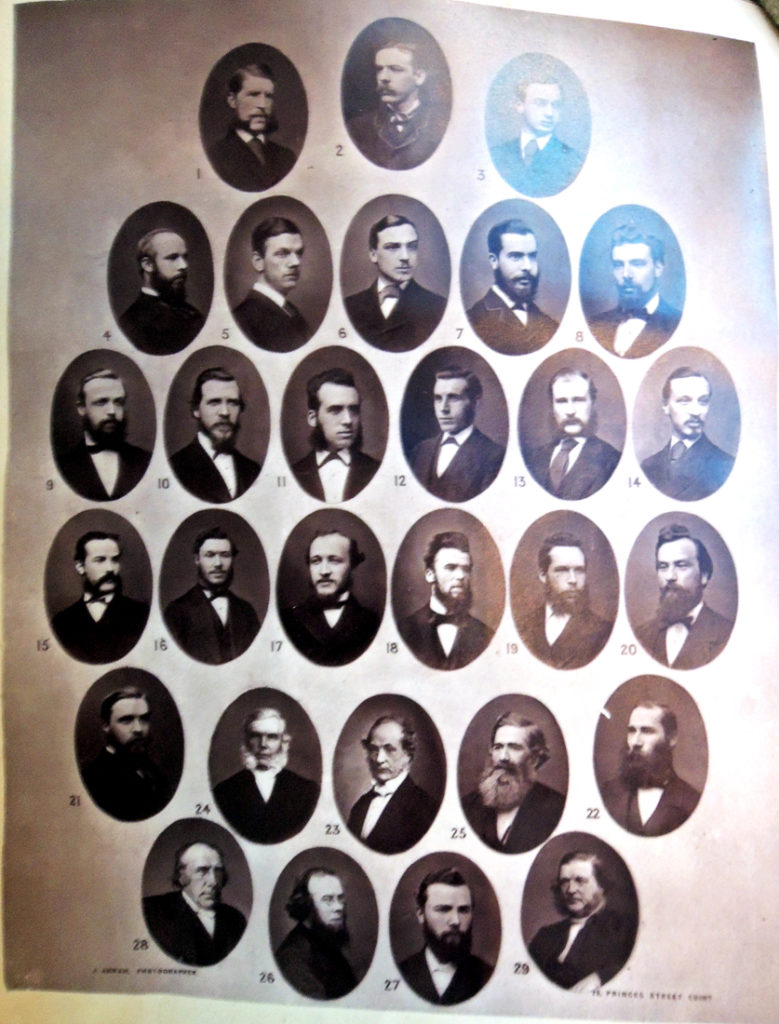

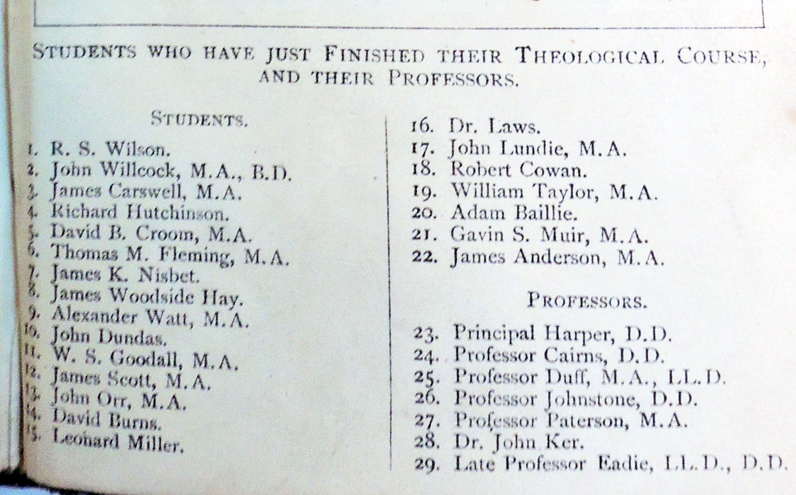

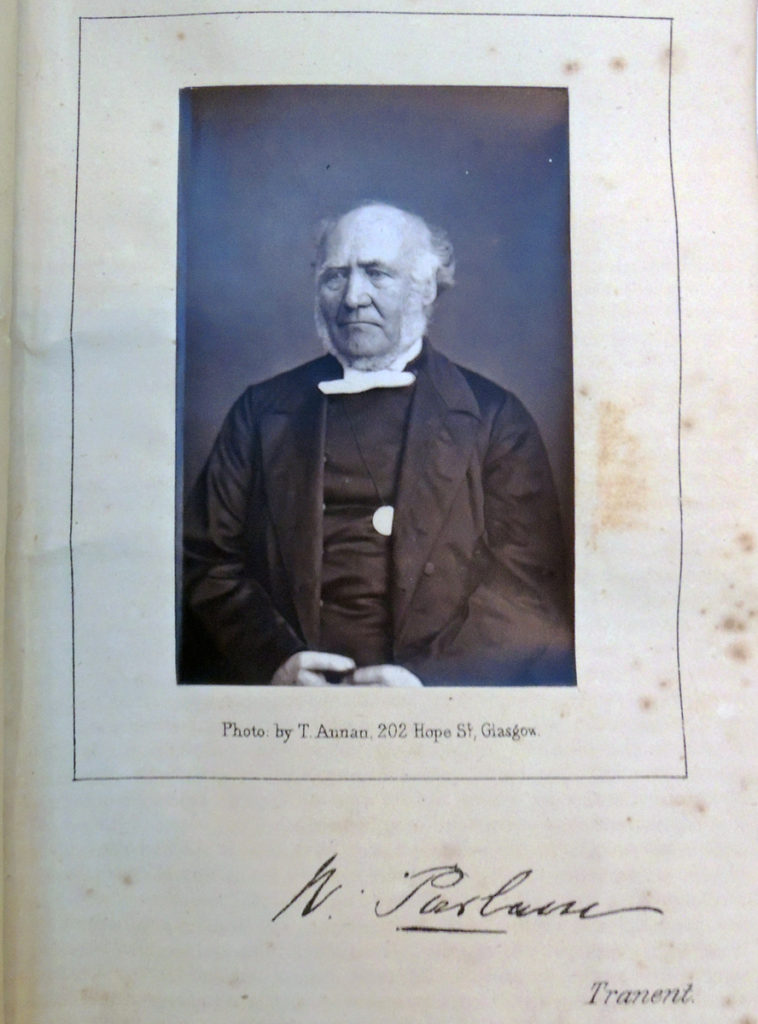

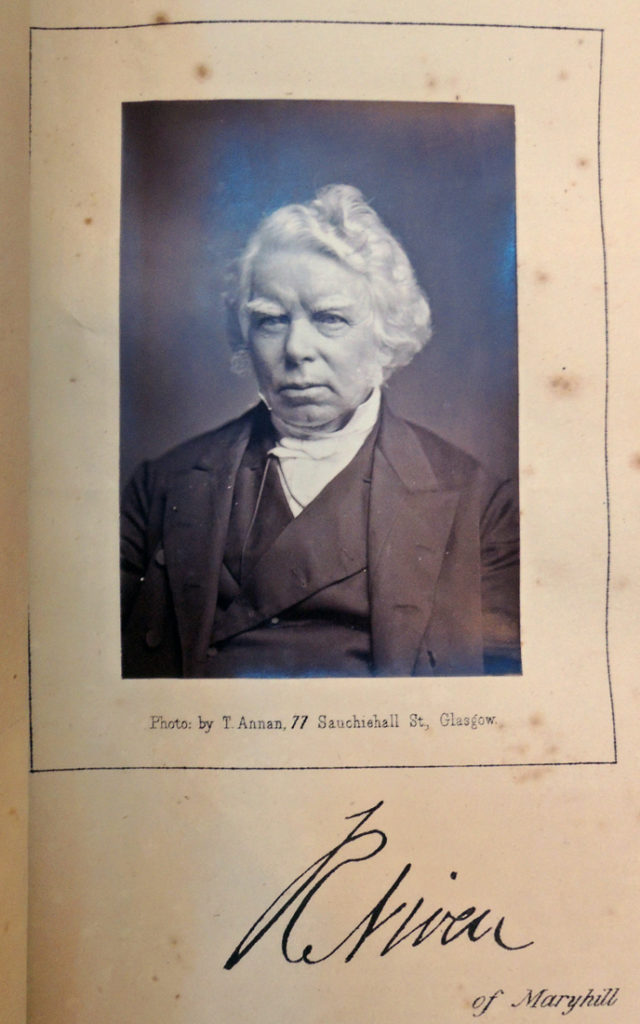

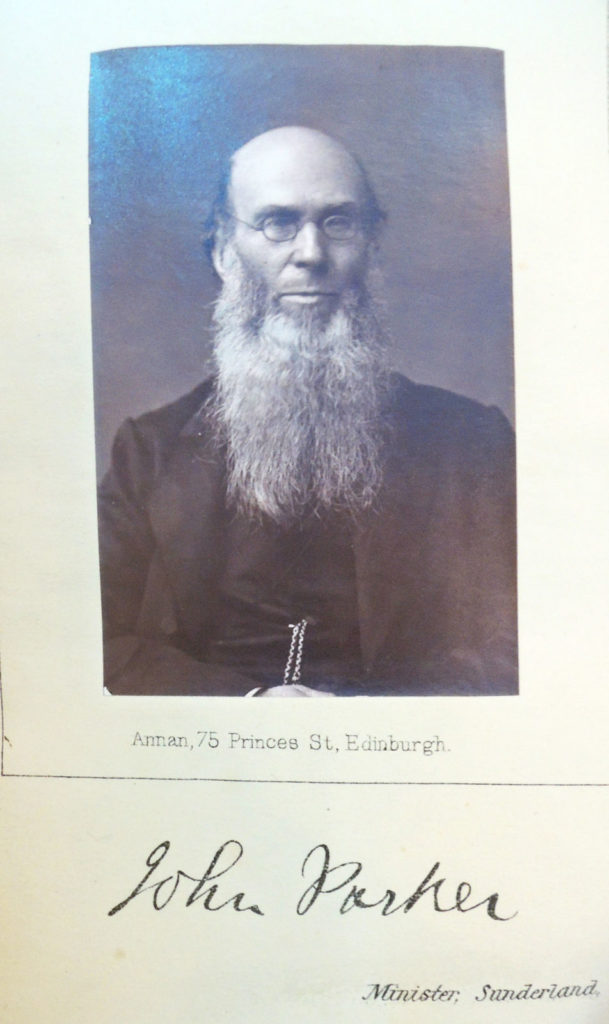

Given that Princeton University has both Presbyterian and Scottish roots, this photography album filled with portraits by Thomas Annan (1829-1887) of ministers, elders, and missionaries affiliated with the United Presbyterian Church of Scotland is a fitting acquisition. [See: Leitch, Alexander. A Princeton Companion.

Given that Princeton University has both Presbyterian and Scottish roots, this photography album filled with portraits by Thomas Annan (1829-1887) of ministers, elders, and missionaries affiliated with the United Presbyterian Church of Scotland is a fitting acquisition. [See: Leitch, Alexander. A Princeton Companion.