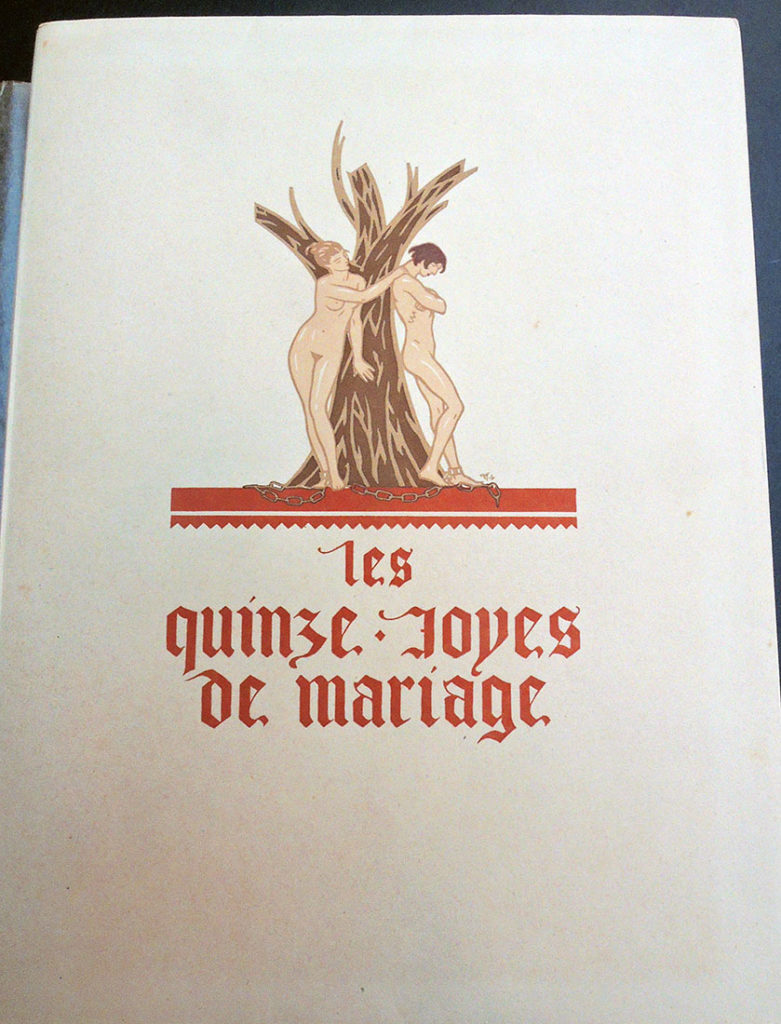

Maurice-Georges-Elie Lalau (1881-1961), Les quinze joyes de mariage … Edition conforme au manuscript de la Bibliothèque de Rouen avec un glossaire publié par Jules Meynial… (Paris, 1928). Copy 45 of 150. Graphic Arts Collection GAX 2018- in process

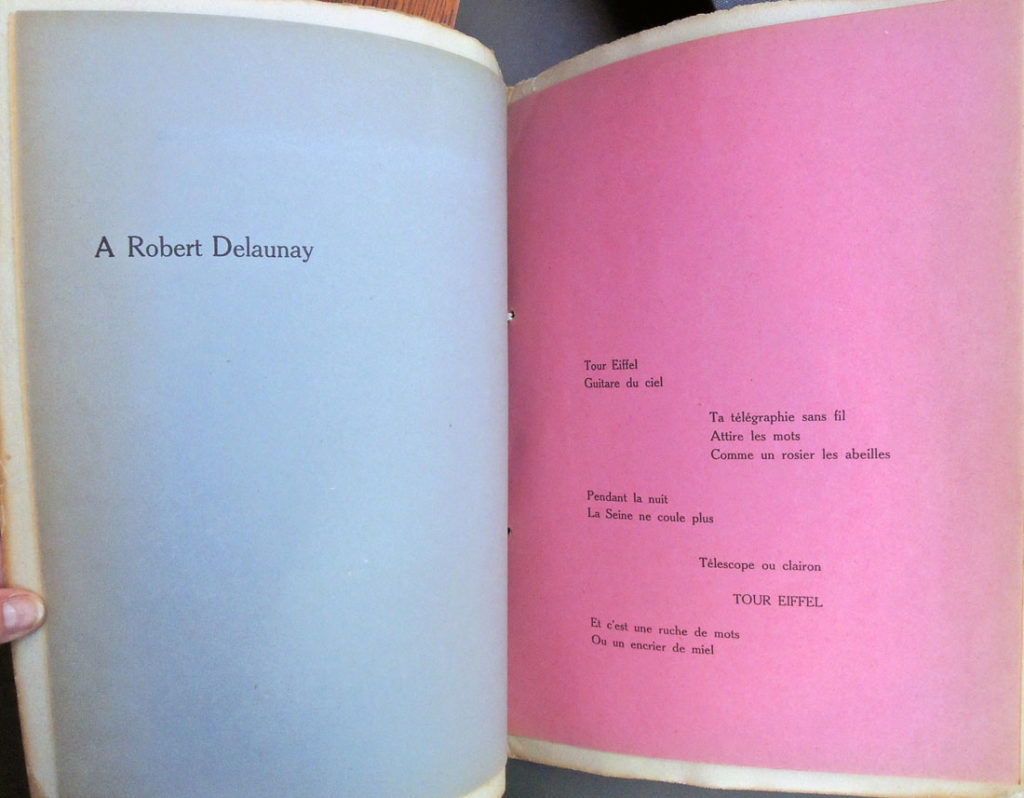

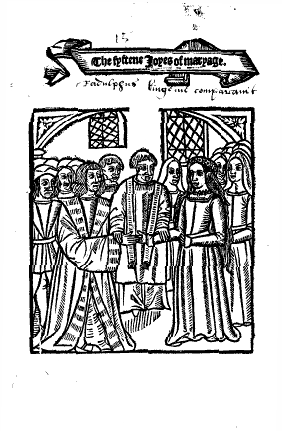

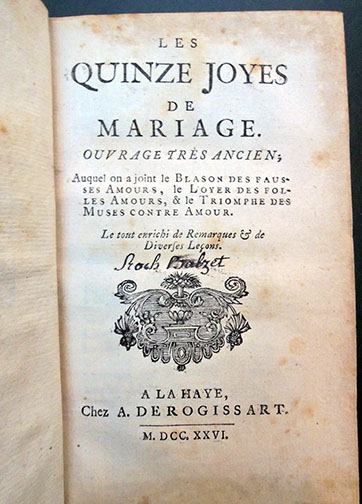

[left] Antoine de La Sale (born 1388?), The Fyftene Joyes of Maryage [Quinze joyes de mariage] ([London: Wynkyn de Worde, 1509]). [right] Les quinze joyes de mariage: ouvrage tres̀ ancien, auquel on a joint le Blason des fausses amours, le Loyer des folles amours, & le Triomphe des muses contre amour. Le tout enrichi de remarques & de diverses leçons (A La Haye: Chez A. De Rogissart, 1726). Rare Books 2004-0836N

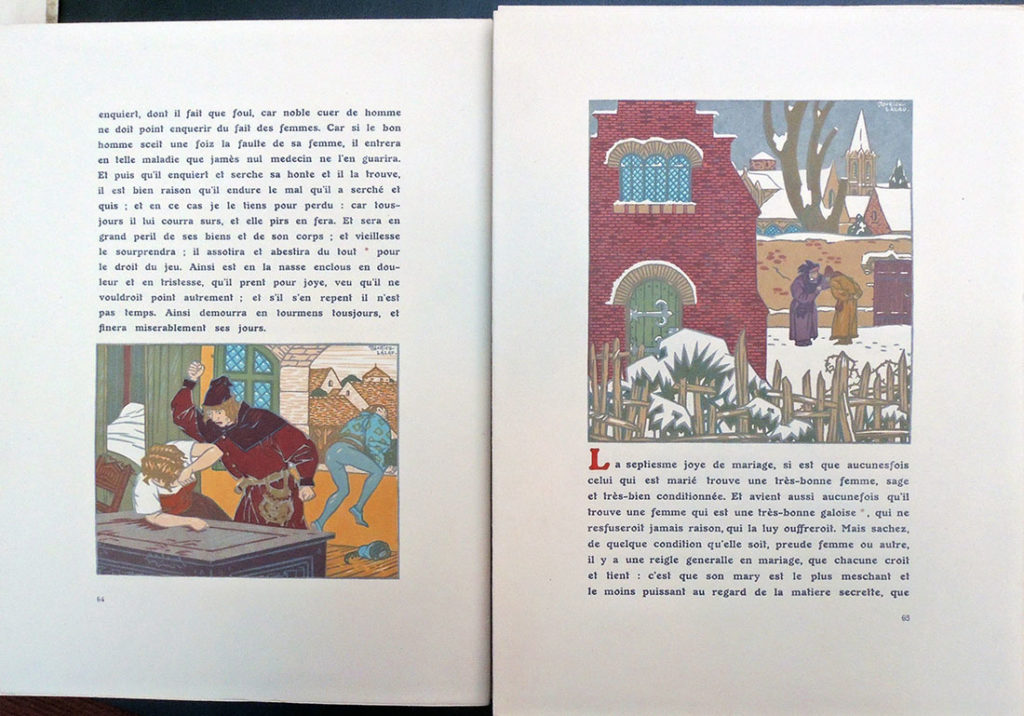

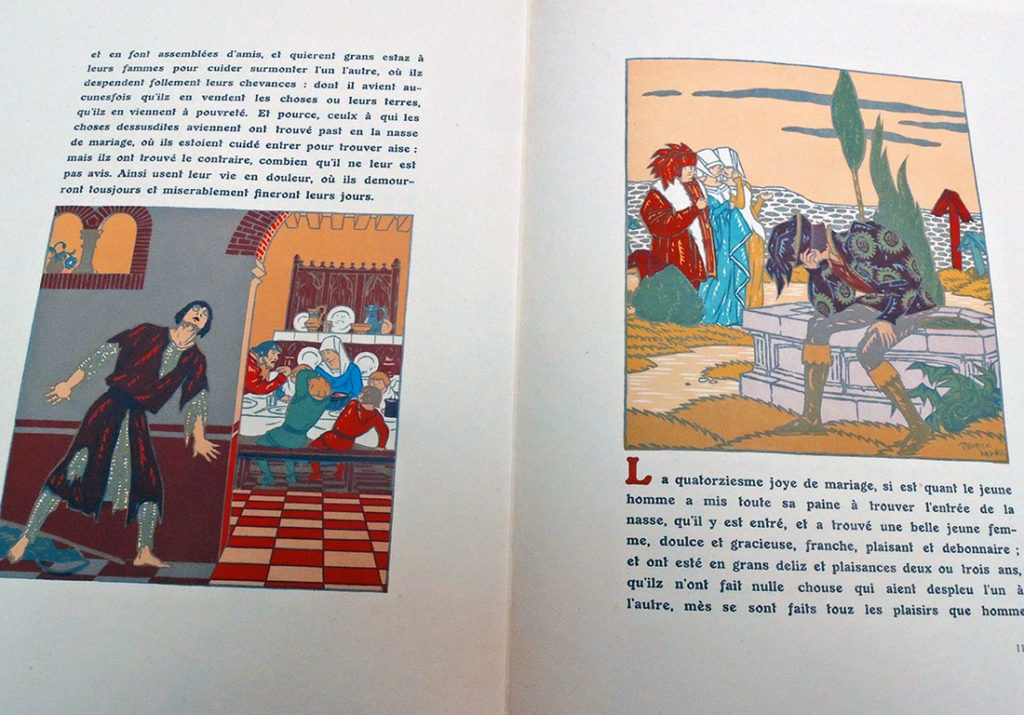

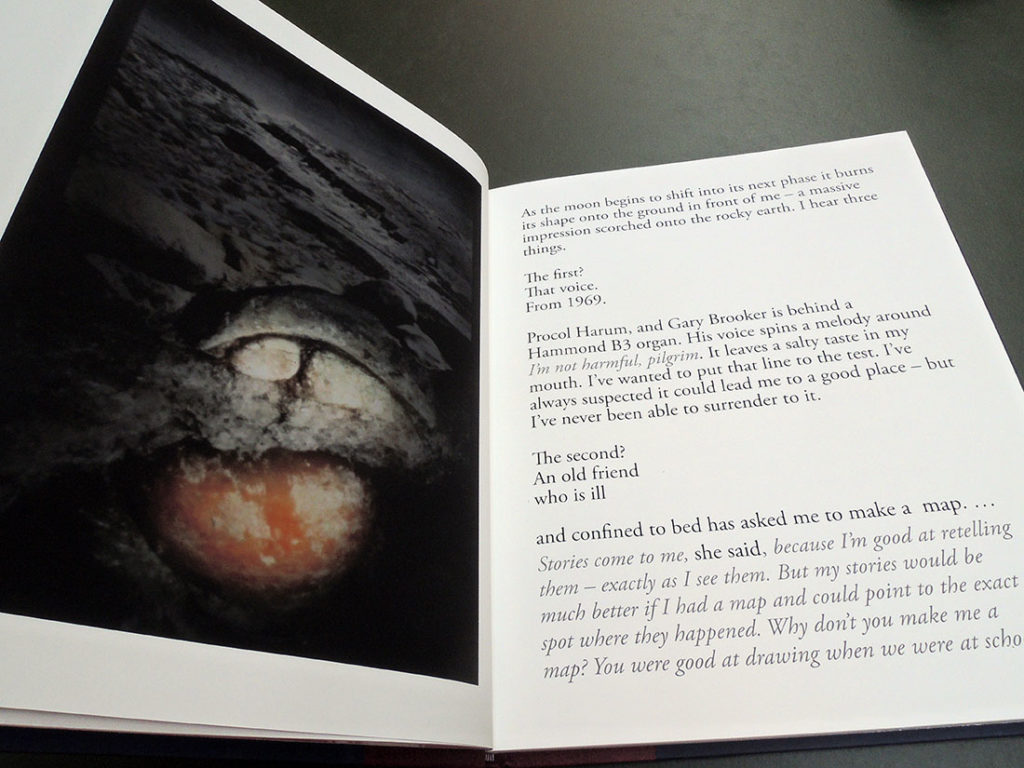

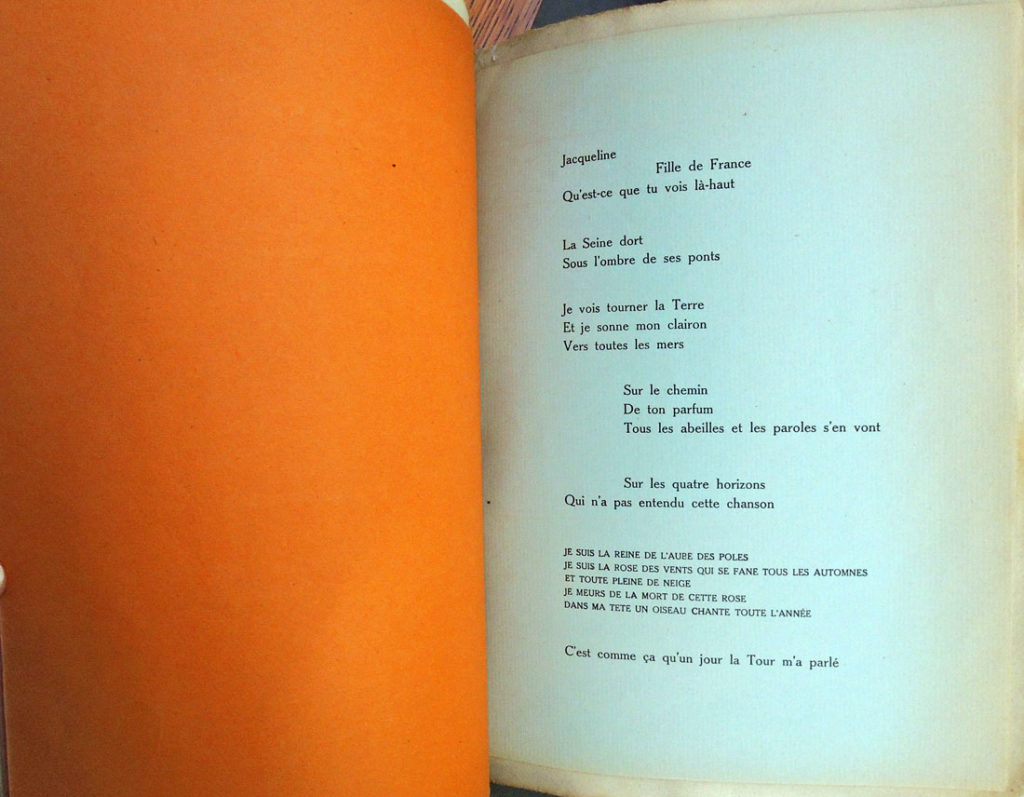

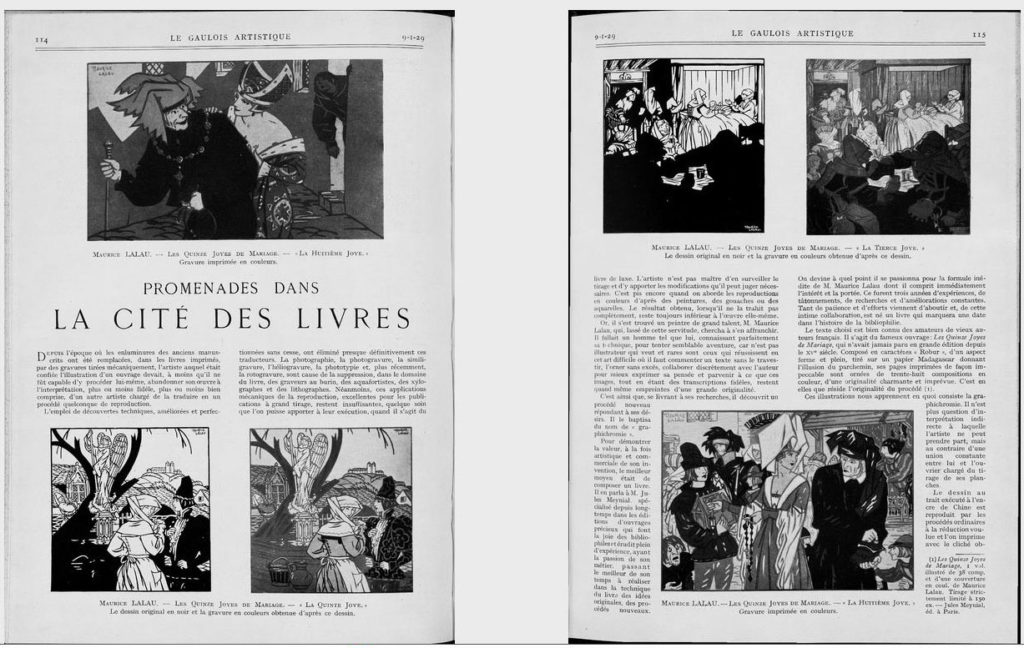

In 1926, Maurice Lalau and the bibliophile/publisher Jules Meynial formed a partnership to create a deluxe edition using innovative printing techniques. For their text, they chose Les quinze joyes, a Medieval satire on the tricks wives play on their husbands, sexual and otherwise.

A 1726 edition [above] has notes by le Duchat, who describes it as a favorite of ‘jeunes Courtisans François’ of the mid-fifteenth century. The work has been attributed to Antoine de la Sale and various dates have been suggested for its composition; le Duchat comes down in favor of the late fourteenth century. Wynkyn de Worde published a translation in English verse, The Fyftene Joyes of Maryage, at least as early as 1507, a fragment of that survives and a single complete copy of a 1509 reprint. STC 15257.5-15258

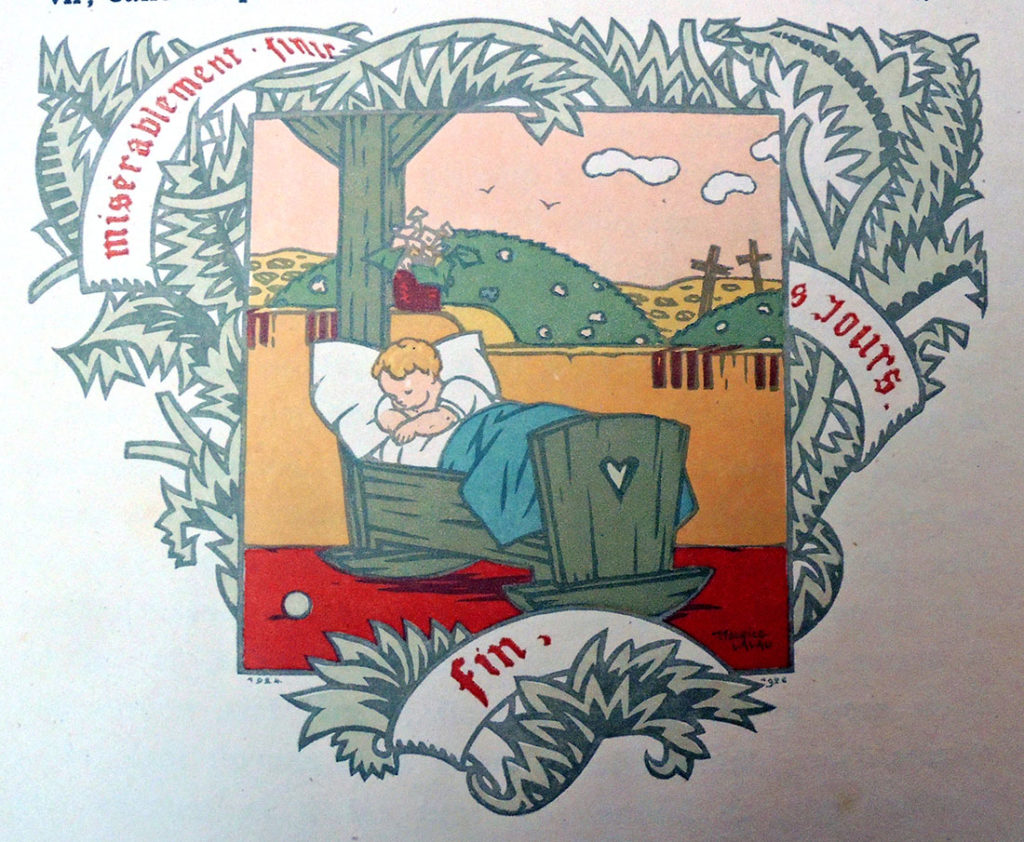

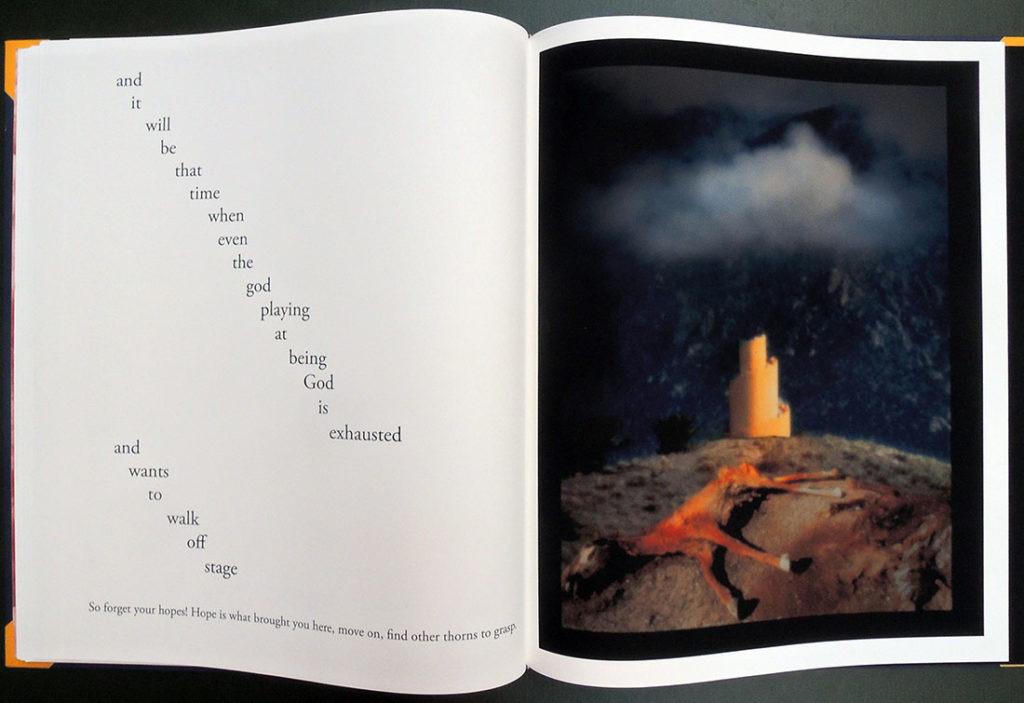

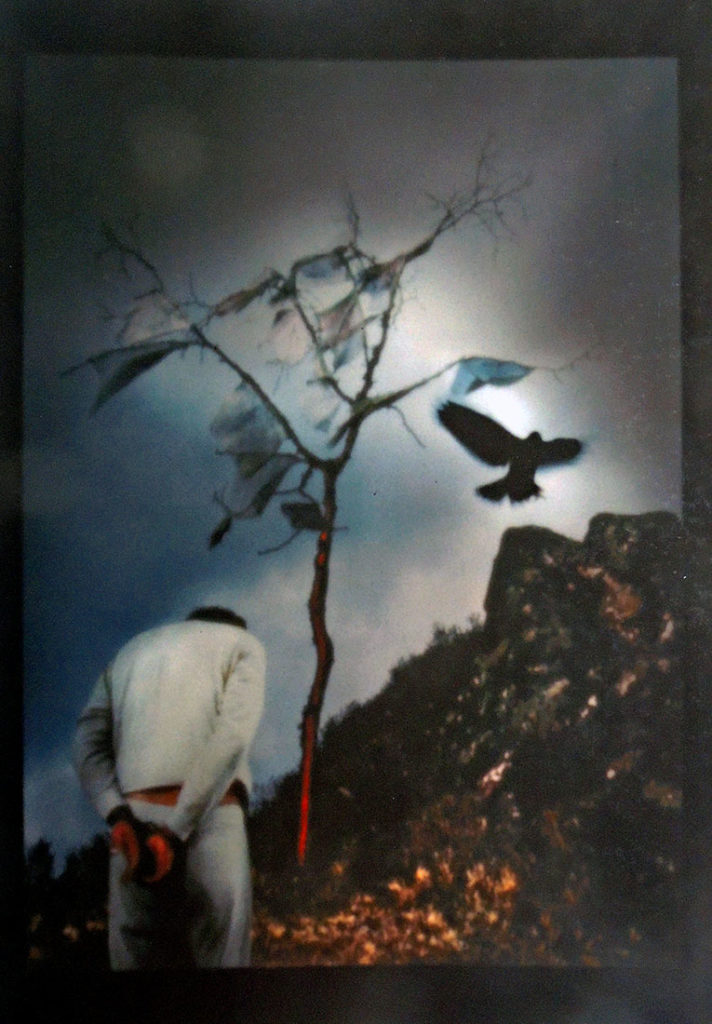

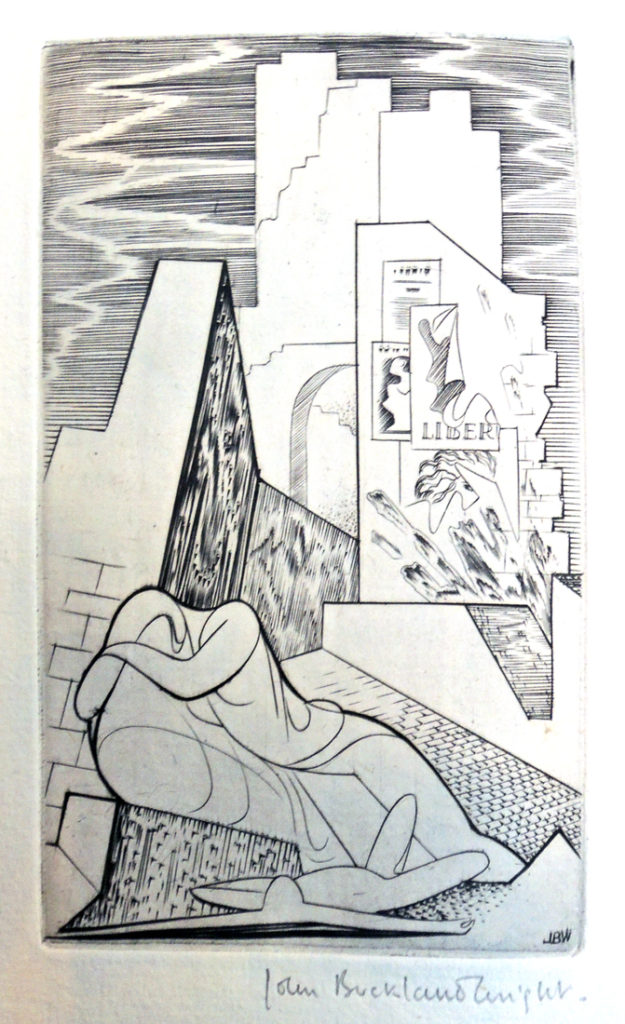

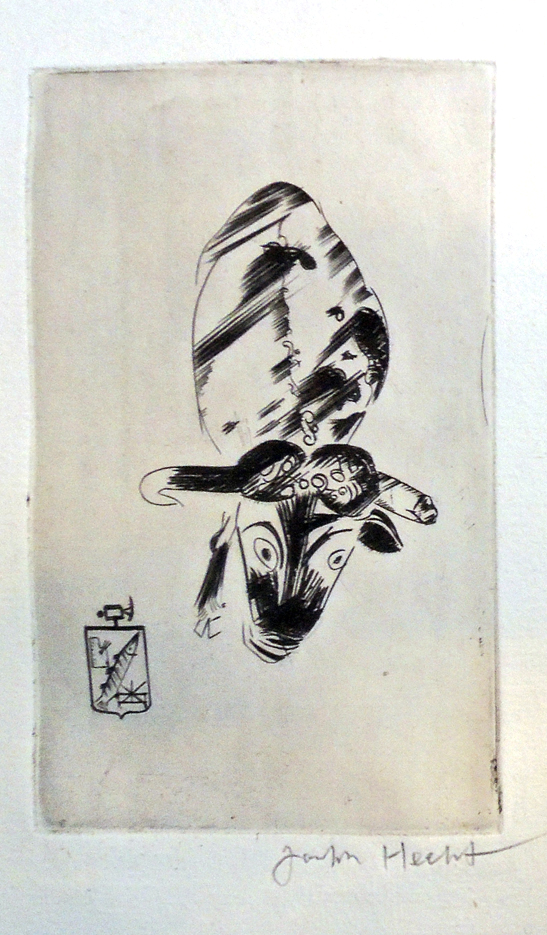

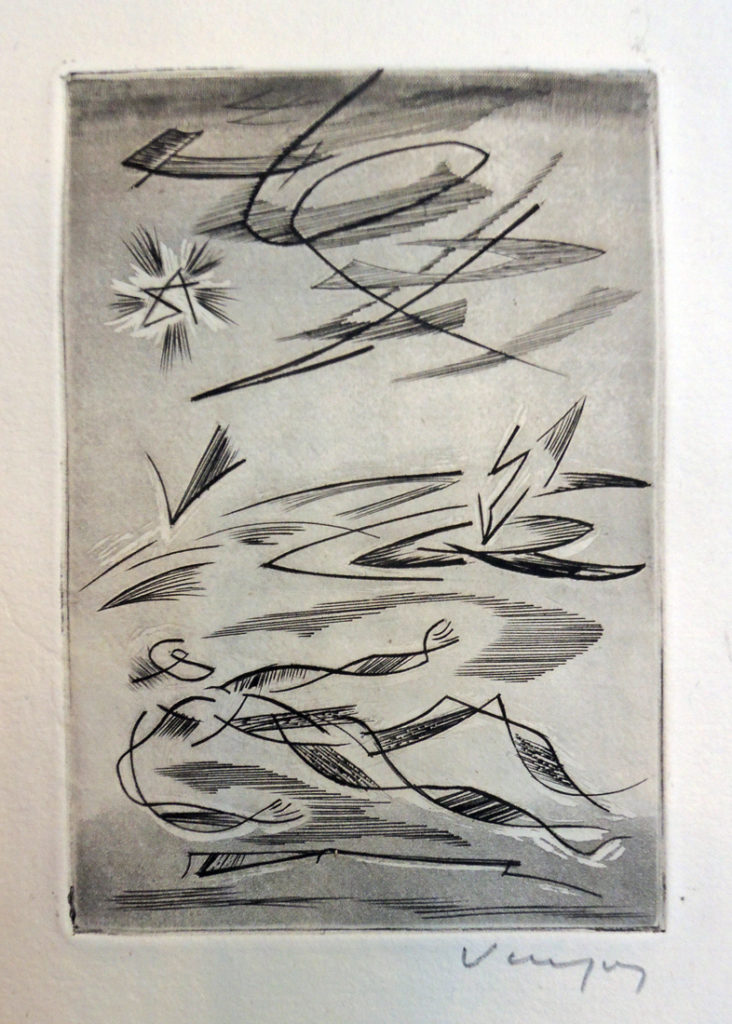

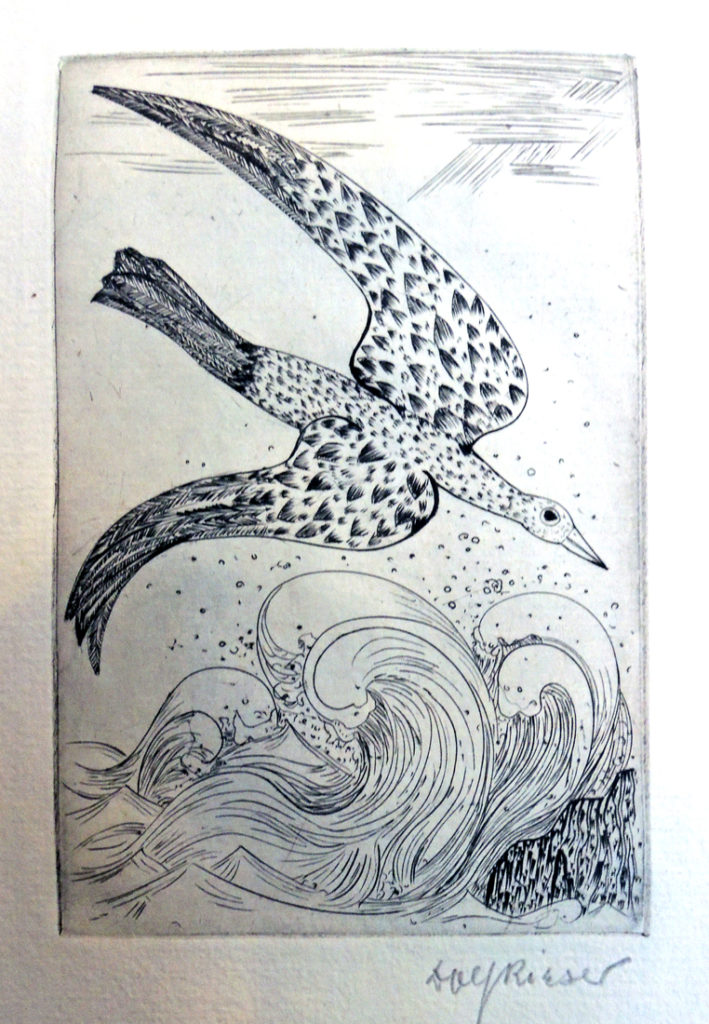

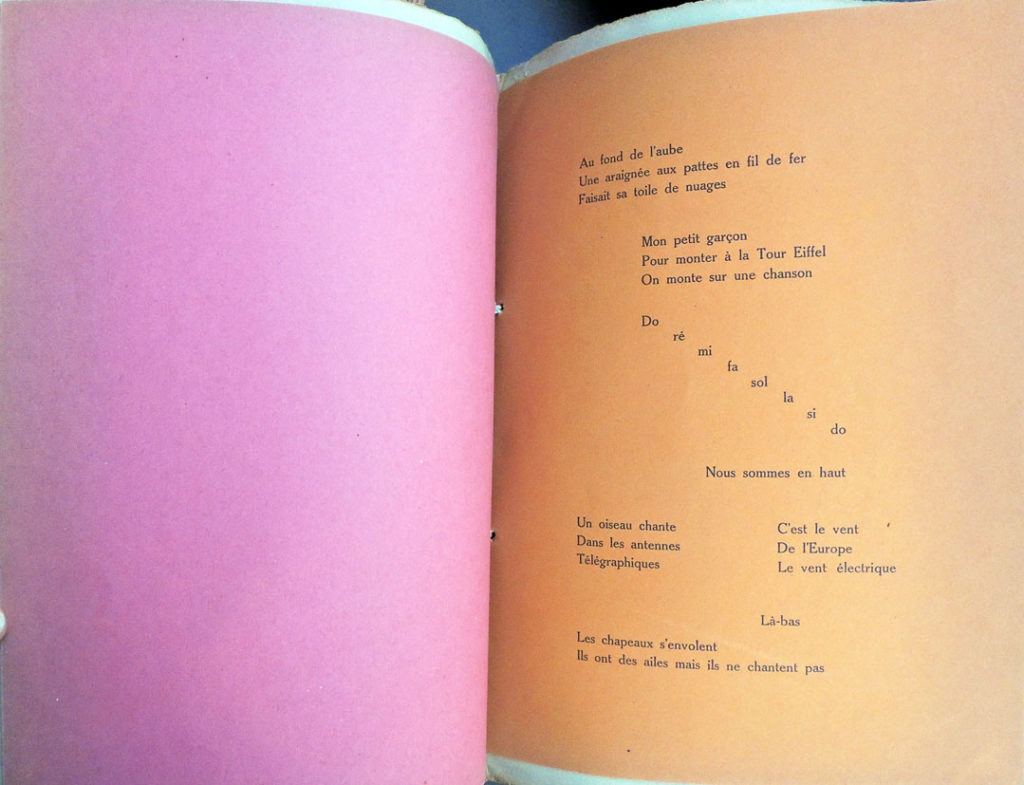

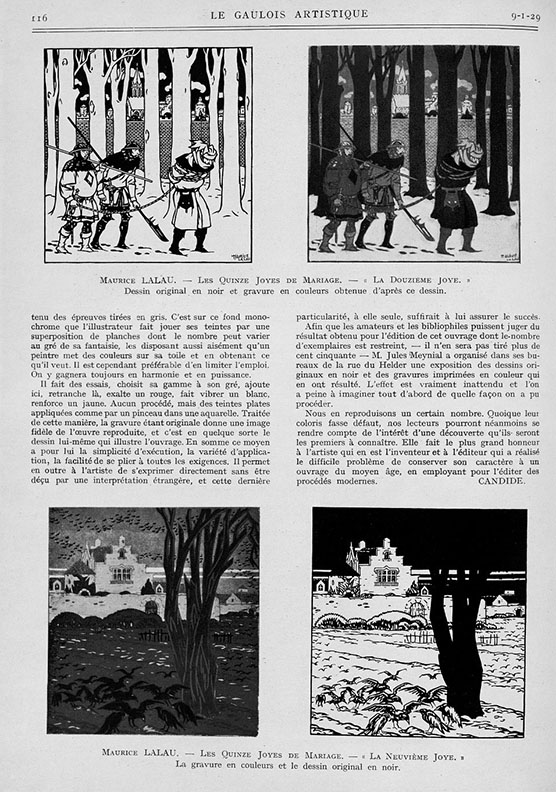

Lalau called his printing process, first seen with this volume, Graphichromie: “un moyen nouveau d’impression des illustrations en couleurs.” He designed and printed the edition of 150 copies, each with 37 plates, which means hand-printing 5,550 multi-color plates. The project took Lalau two years to complete. In addition, this copy has 37 single leaves, reproducing the illustrations in grey ink only (the initial color in the process).

Their book was the subject of an article in the January 1929 issue of Le Gaulois artistique, [above and left] in which the author laments the suppression of traditional illustration processes in favor of newer mechanical techniques:

Their book was the subject of an article in the January 1929 issue of Le Gaulois artistique, [above and left] in which the author laments the suppression of traditional illustration processes in favor of newer mechanical techniques:

“L’emploi de découvertes techniques, améliorées et perfectionées sans cesse, ont éliminé presque définitivement ces traducteurs. La photographie, la photogravure, la similigravure, l’héliogravure, la phototype et, plus récemment, la rotogravure, sont cause de la suppression, dans la domaine du livre, des graveurs au burin, des aquafortistes, des xylographes et des lithographes.

Néanmoins, ces applications mécaniques de la reproduction, excellentes pour les publications à grand tirage, resente insuffisantes, quelque soin que l’on puisse apporter à leur execution, quand il s’agit du livre du luxe.”

Although the author disdains mechanical processes, in general, he praises Lalau’s technique for its insistence on intimacy between artist and workman:

“Il n’est plus question d’interprétation indirecte à laquelle l’artiste ne peut prendre part, mais au contraire d’une union constante entre lui et l’ouvrier chargé du tirage de ses planches.”

In addition, he compliments Lalau’s ability to convey the spirit of the Middle Ages through modern mechanical means: “Elle fait le plus grand honneur à l’artiste qui en est l’inventeur et à l’éditeur qui a réalisé le difficile problème de conserver son caractère à un ouvrage du moyen âge, en employant pour l’éditer des proceeds modernes.”