This 1940s silent movie shows basic lithography on stone, on zinc, photolithography on glass and then, on zinc plate. It is slow but worth the wait.

Category Archives: Books

Miseries Installed

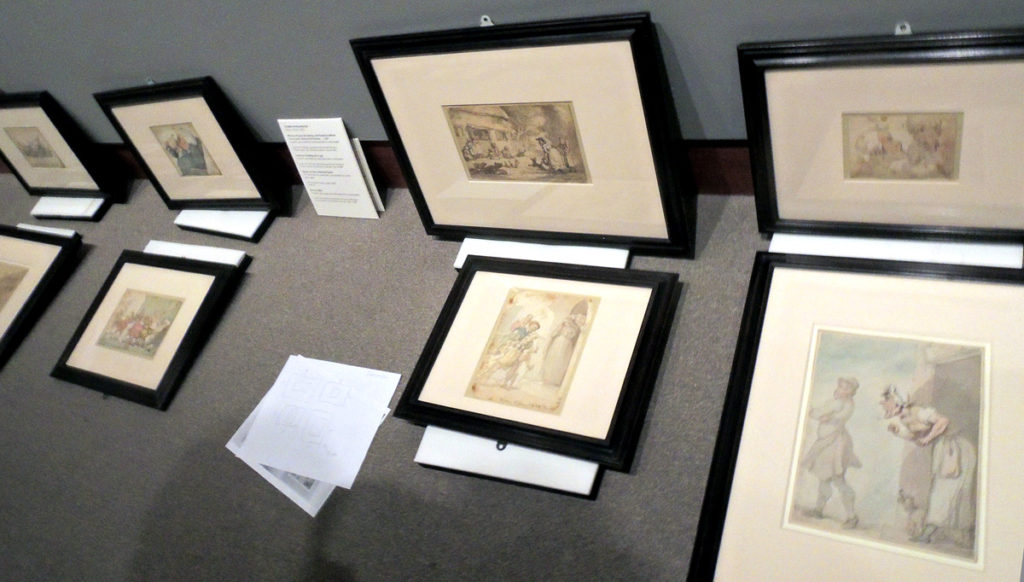

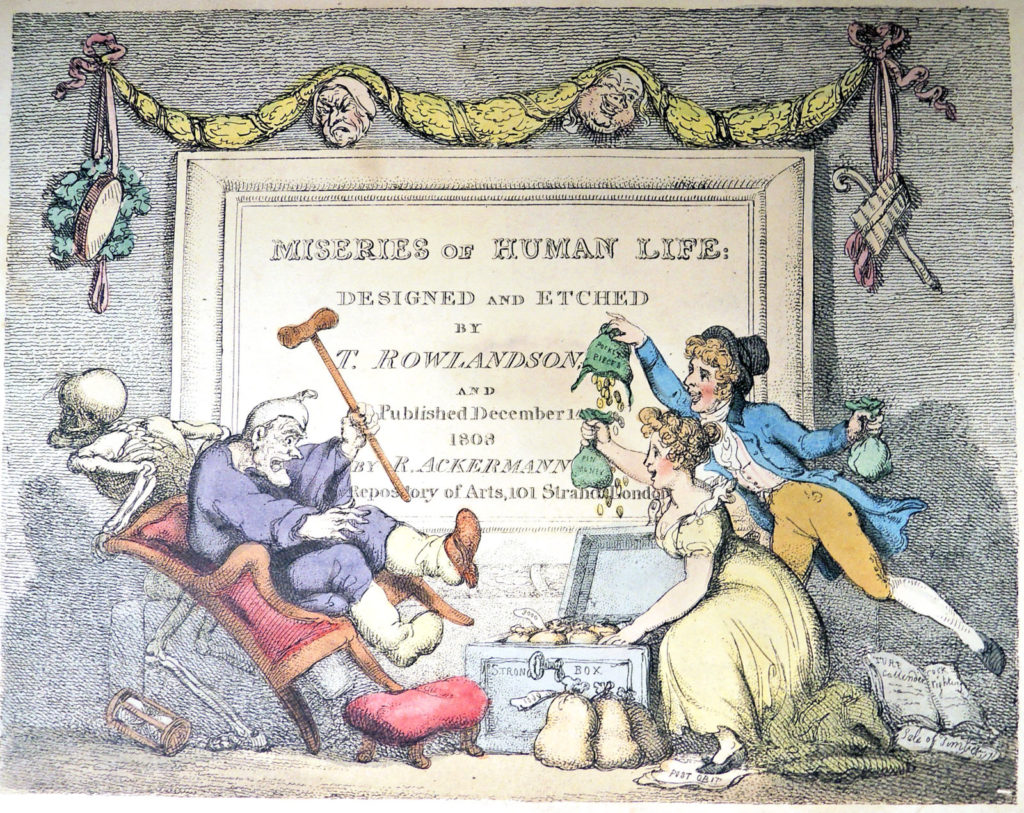

On Saturday, July 1, 2017, a small show will open at the Princeton University Art Museum titled, The Miseries of Human Life and Other Amusements: Drawings by Thomas Rowlandson.

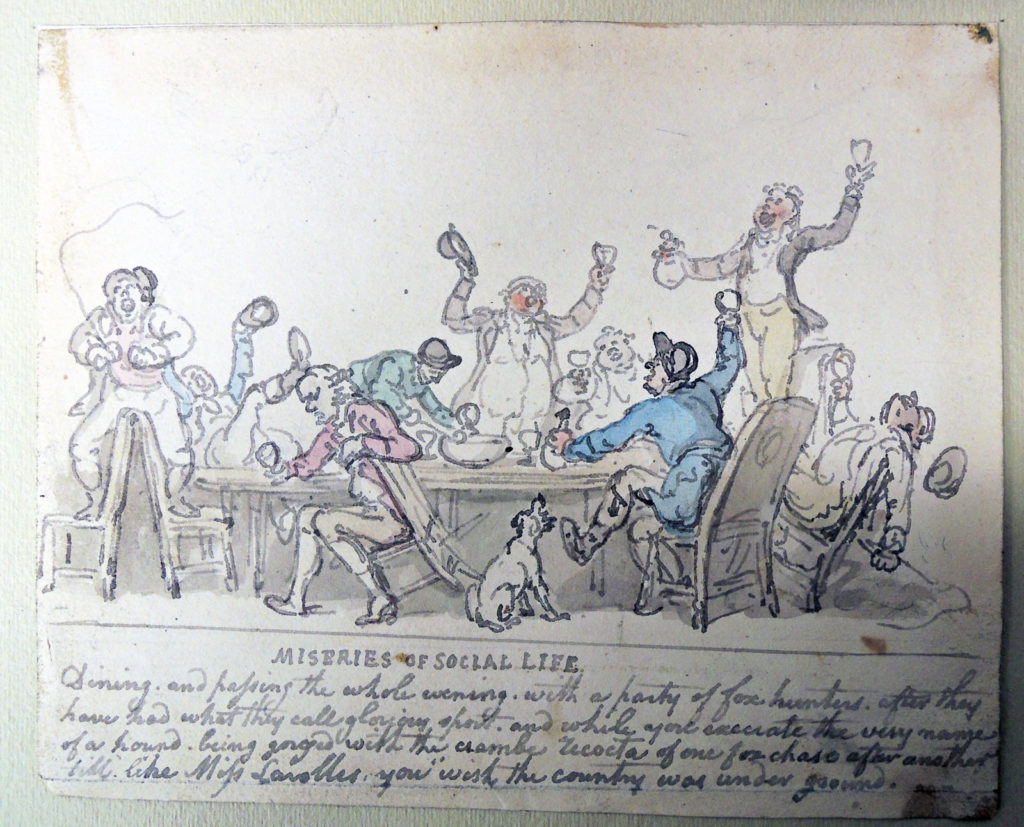

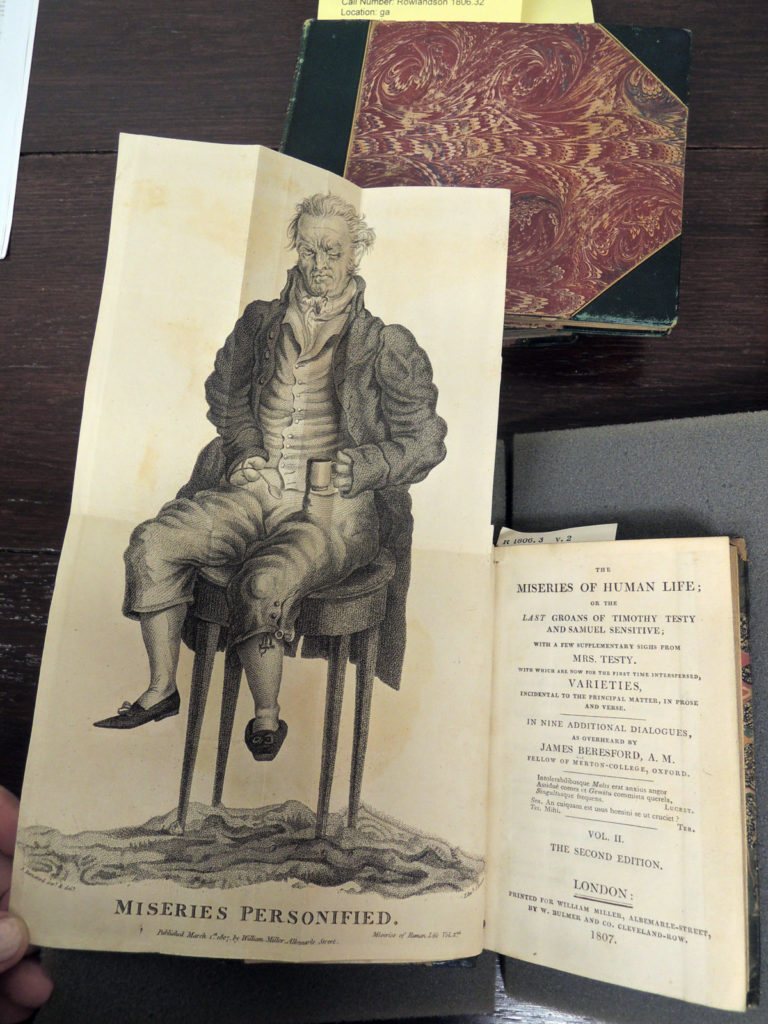

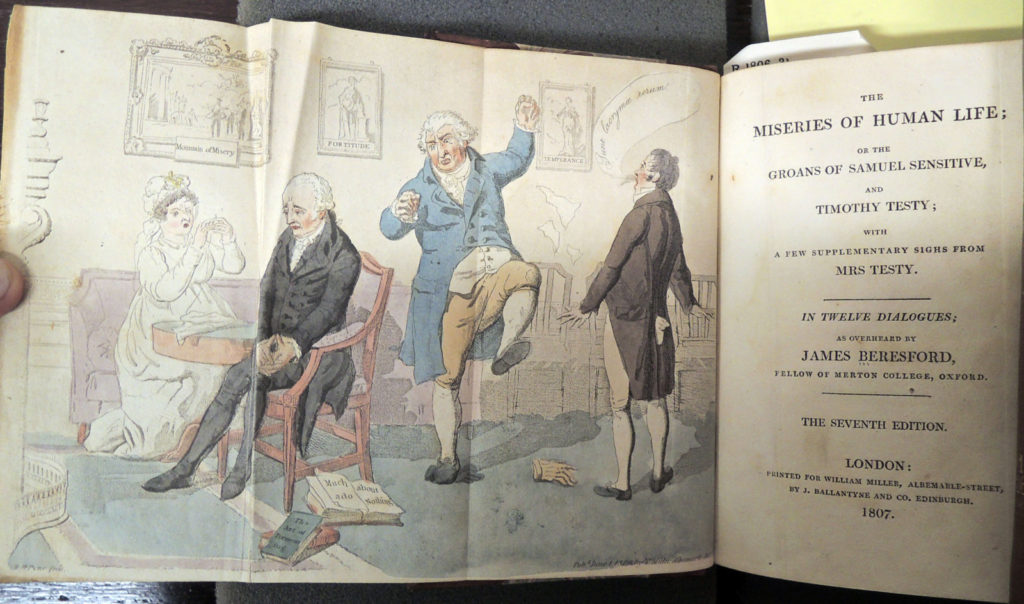

Written in 1806 by James Beresford (1764–1840), The Miseries of Human Life was extraordinarily successful, becoming a minor classic in the satirical literature of the day. Through a humorous dialogue between two old curmudgeons, the book details the “petty outrages, minor humiliations, and tiny discomforts that make up everyday human existence.”

The public loved it, dozens of editions were published, and printmakers rushed to illustrate their own versions of life’s miseries.

Thomas Rowlandson (1756/57–1827) began drawing scenes based on Beresford’s book as soon as it was published and after two years, the luxury print dealer Rudolph Ackermann (1764-1834) selected fifty of his hand colored etchings for a new edition of Miseries. Many of the now-iconic characters and situations that the artist drew for this project—some based closely on Beresford’s text and others of his own invention—reappeared in later works, with variations on the Miseries turning up until the artist’s death.

In the early twentieth century, Dickson Q. Brown, Class of 1895, donated two thousand Rowlandson prints and all of the artist’s illustrated books to the Princeton University Library. Of particular importance was a small box of Rowlandson’s unpublished, undated drawings, including many specifically related to his Miseries series.

In the early twentieth century, Dickson Q. Brown, Class of 1895, donated two thousand Rowlandson prints and all of the artist’s illustrated books to the Princeton University Library. Of particular importance was a small box of Rowlandson’s unpublished, undated drawings, including many specifically related to his Miseries series.

Here, in its first public presentation, is a selection of Rowlandson’s drawings from Brown’s donation. Just as in Rowlandson’s book, those specific to Beresford’s text are shown alongside others that illustrate life’s miseries more generally, including some from the Princeton University Art Museum’s collection. The sections follow the chapters, or “groans,” of Beresford’s book.

Particular thanks go to Laura Giles for suggesting a show of the library’s Rowlandson drawings. Princeton University Art Museum: http://artmuseum.princeton.edu/

The exhibition runs through October 2017, with a talk entitled “That’s So Annoying! Thomas Rowlandson and The Miseries of Human Life,” on Sunday, September 17, 2017, at 2:00 p.m. in 101 McCormick Hall, Princeton University

The exhibition runs through October 2017, with a talk entitled “That’s So Annoying! Thomas Rowlandson and The Miseries of Human Life,” on Sunday, September 17, 2017, at 2:00 p.m. in 101 McCormick Hall, Princeton University

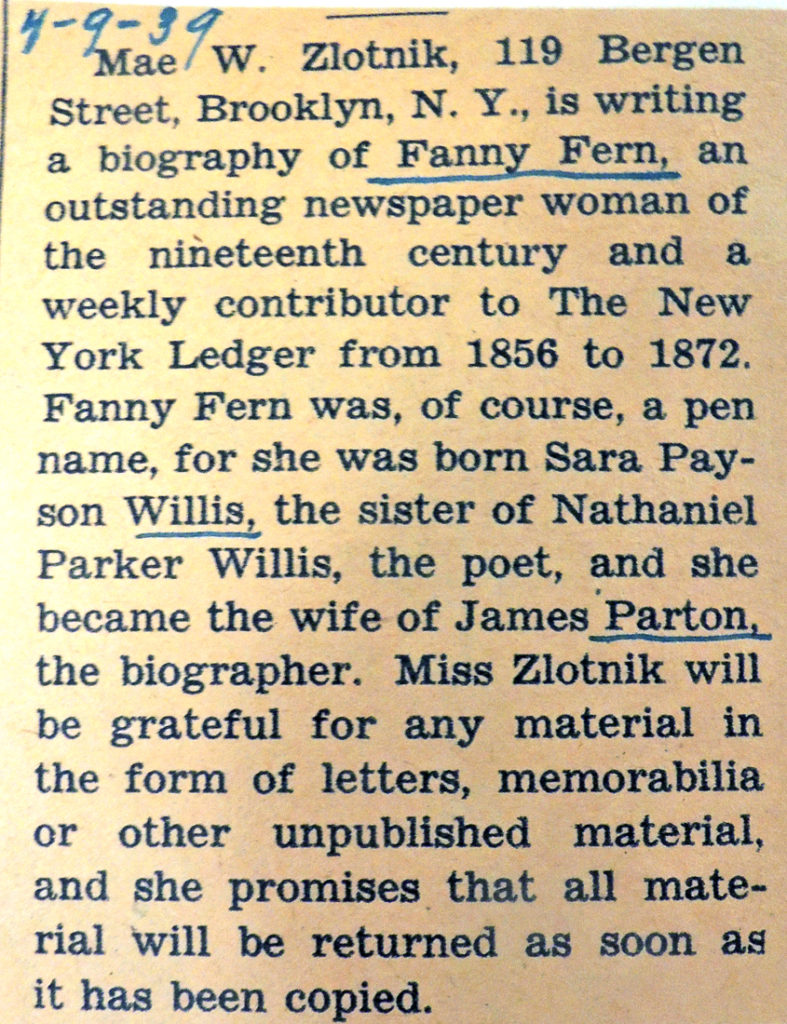

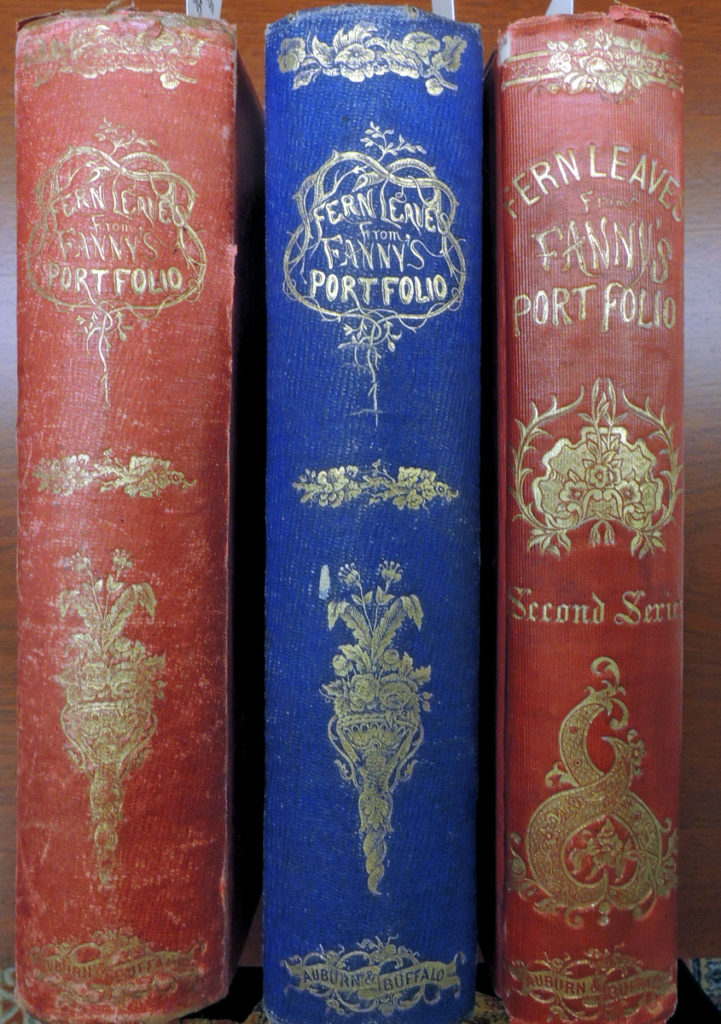

100,000 copies sold in 1853

Several of the Sinclair Hamilton Collection copies of the collected stories by the author, journalist, columnist, and humorist Sara Payson Willis (1811-1872) are filled with clippings and other notes about the writer and the illustrators. Willis wrote for several small Boston magazines under the pen-name Fanny Fern, including a weekly column in the New York Ledger read by hundreds of thousands of fans across the country. Willis is considered one of, if not the first American woman columnist. She continued to publish a column every week until her death in 1872.

Several of the Sinclair Hamilton Collection copies of the collected stories by the author, journalist, columnist, and humorist Sara Payson Willis (1811-1872) are filled with clippings and other notes about the writer and the illustrators. Willis wrote for several small Boston magazines under the pen-name Fanny Fern, including a weekly column in the New York Ledger read by hundreds of thousands of fans across the country. Willis is considered one of, if not the first American woman columnist. She continued to publish a column every week until her death in 1872.

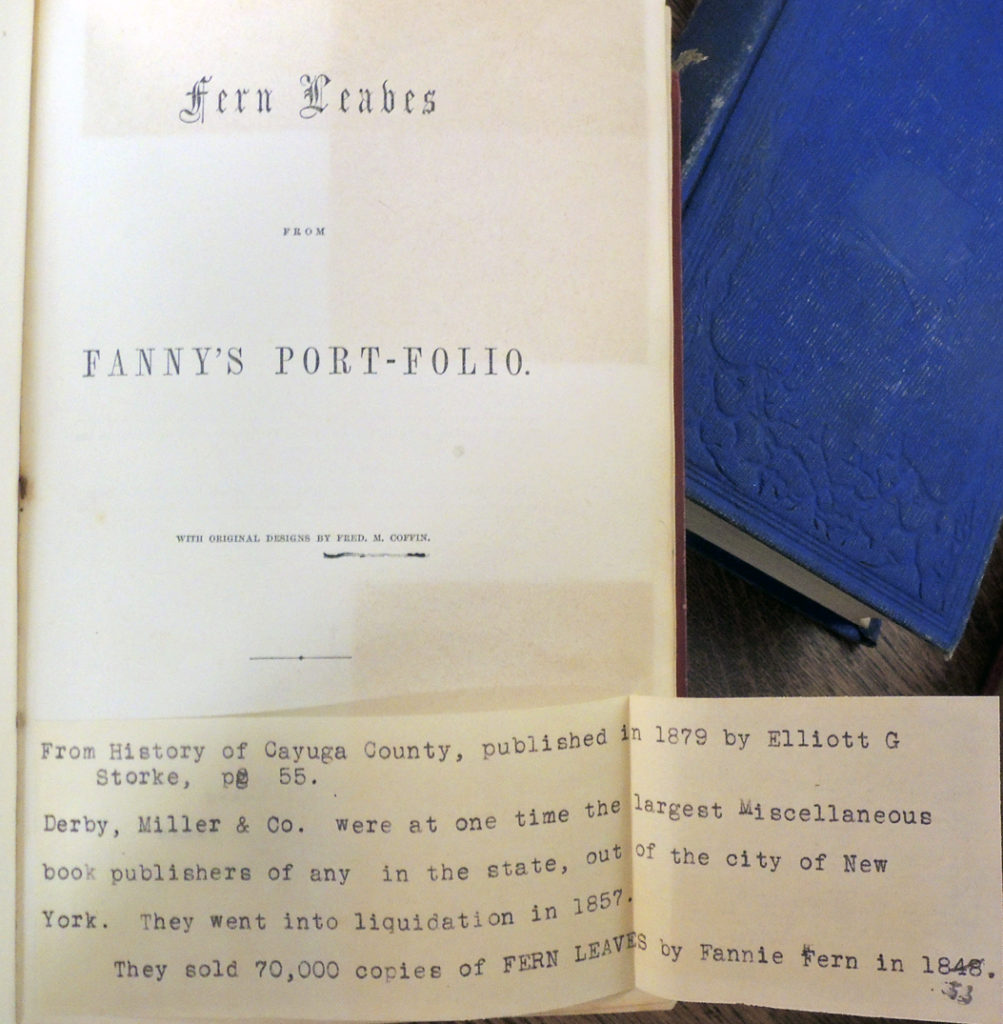

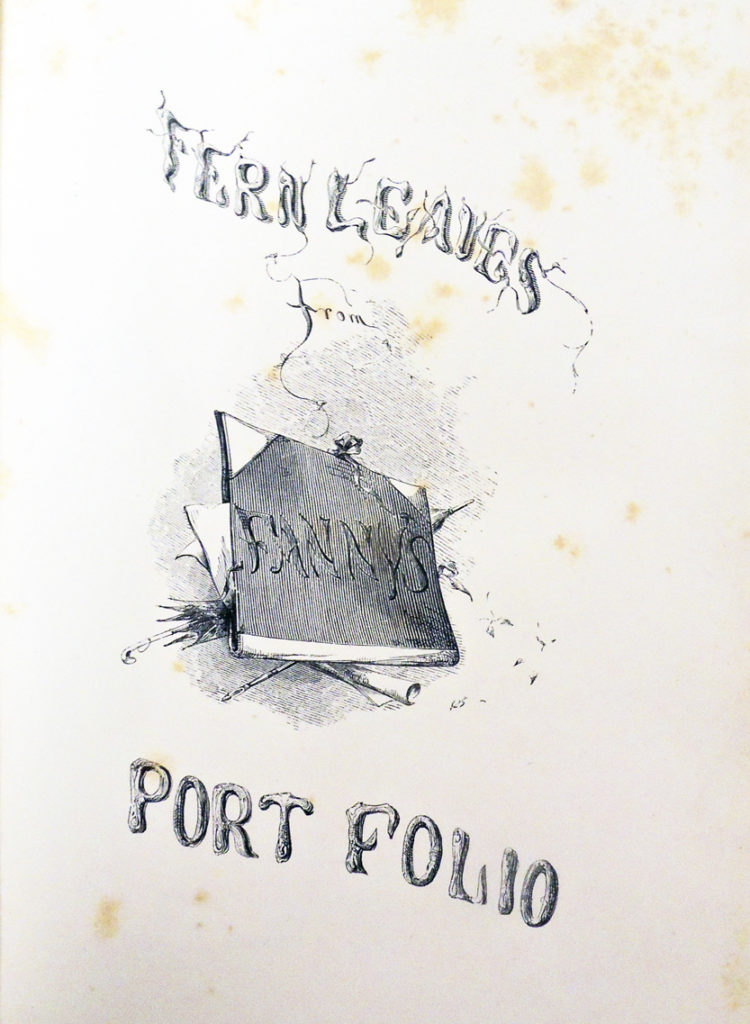

Her 1853 collection of articles, published under the title Fern Leaves from Fanny’s Port-Folio, was an immediate success, recorded as selling nearly 100,000 copies the first year. Six other collections followed, including Fresh Leaves (1857), Folly as It Flies (1859), Ginger-Snaps (1870), and Caper-Sauce (1872). https://fannyfern.org/bio

Hamilton’s note recording her sales at 70,000 has since be changed to nearly 100,000.

Hamilton’s note recording her sales at 70,000 has since be changed to nearly 100,000.

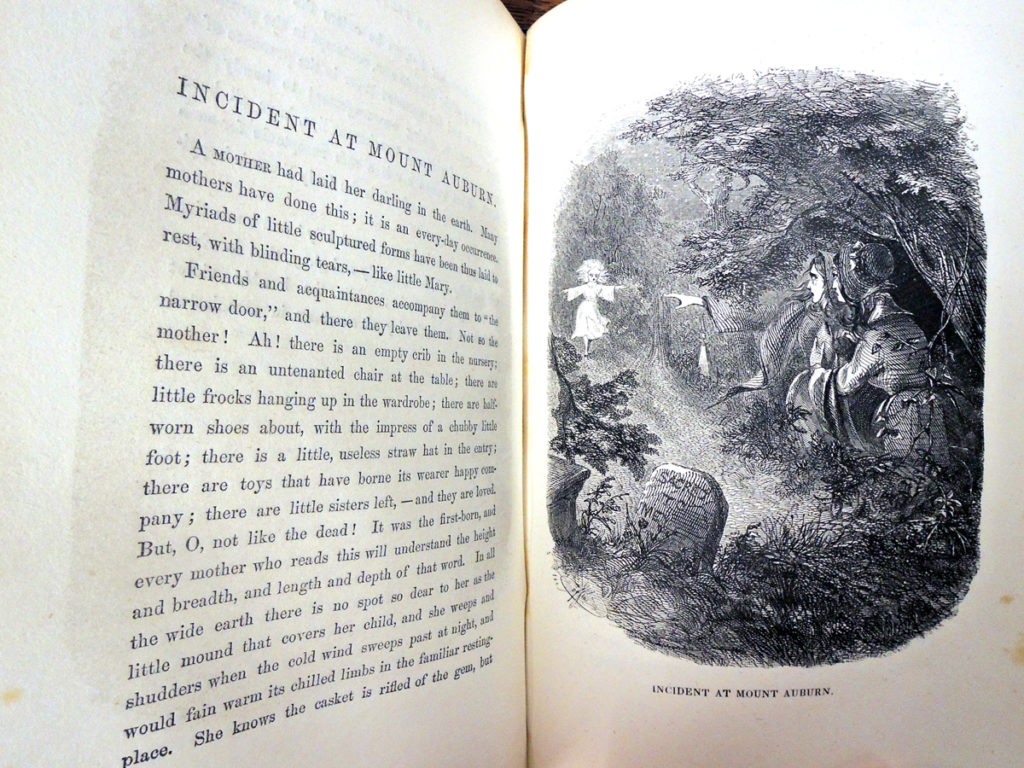

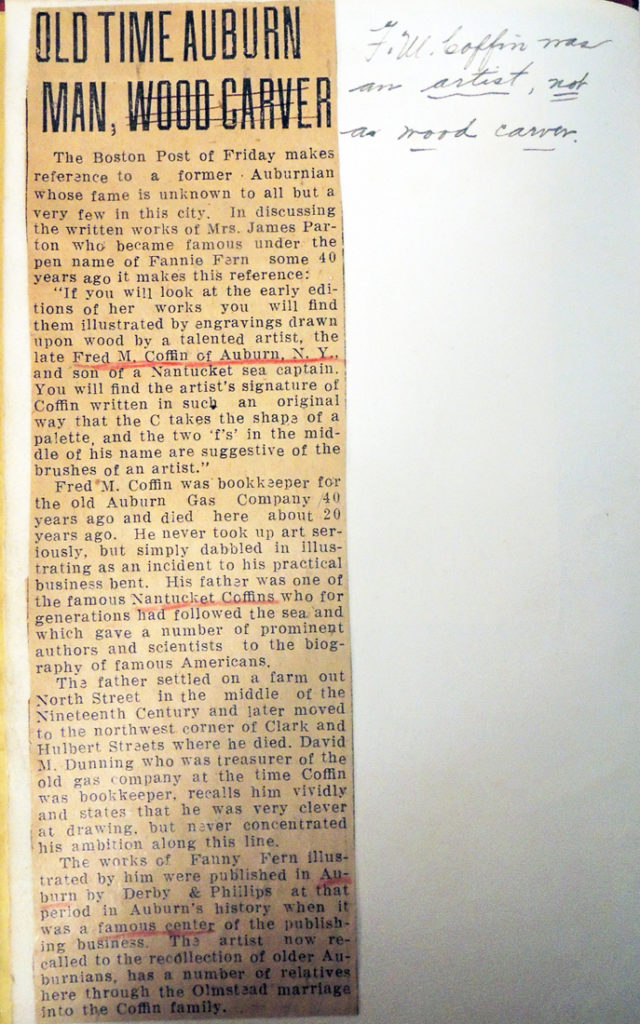

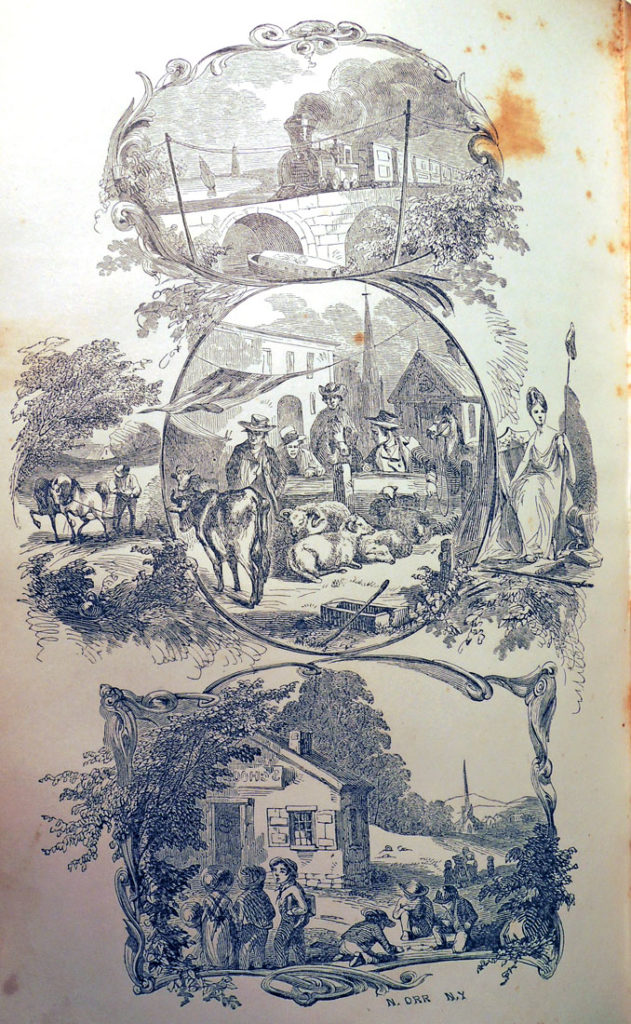

Design and wood engraving by Nathaniel Orr.

Design and wood engraving by Nathaniel Orr.

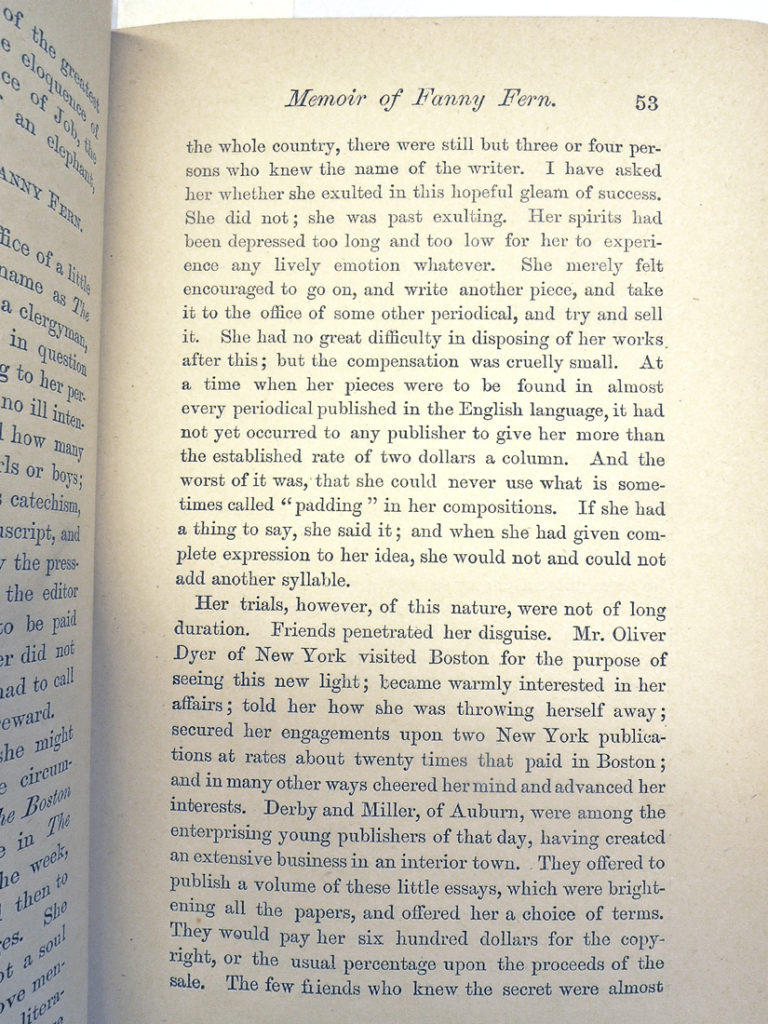

“When her first husband died of typhoid fever in 1846, Sara’s father and her in-laws did not want to support her and her two children. She tried her luck at being a seamstress, one of the only respectable positions available to women, but could not make ends meet. She also attempted to secure a teaching position, but was not successful. At her father’s insistence, Sara embarked on a marriage of convenience that ended in divorce. Because Sara left her abusive husband, the scandal further alienated her from her family and friends. In a desperate attempt to feed her children, Sara began writing articles for Boston newspapers in 1851. Shortly thereafter, her articles were read in newspapers nationwide and in England.” –Giuliana Lonigro, “Women’s History Month Profile: Sara Payson Willis (“Fanny Fern”)”

In an article published in New York Life on August 8, 1867, Fern wrote: “I look around and see innumerable women to whose barren, loveless life [writing] would be improvement and solace, and I say to them, write! Write if it will make your life brighter, or happier, or less monotonous. Write! It will be a safe outlet for thoughts and feelings…[L]ift yourselves out of the dead level of your lives…Fight it! Oppose it, for your own sakes, and your children’s! Do not be mentally annihilated by it.”

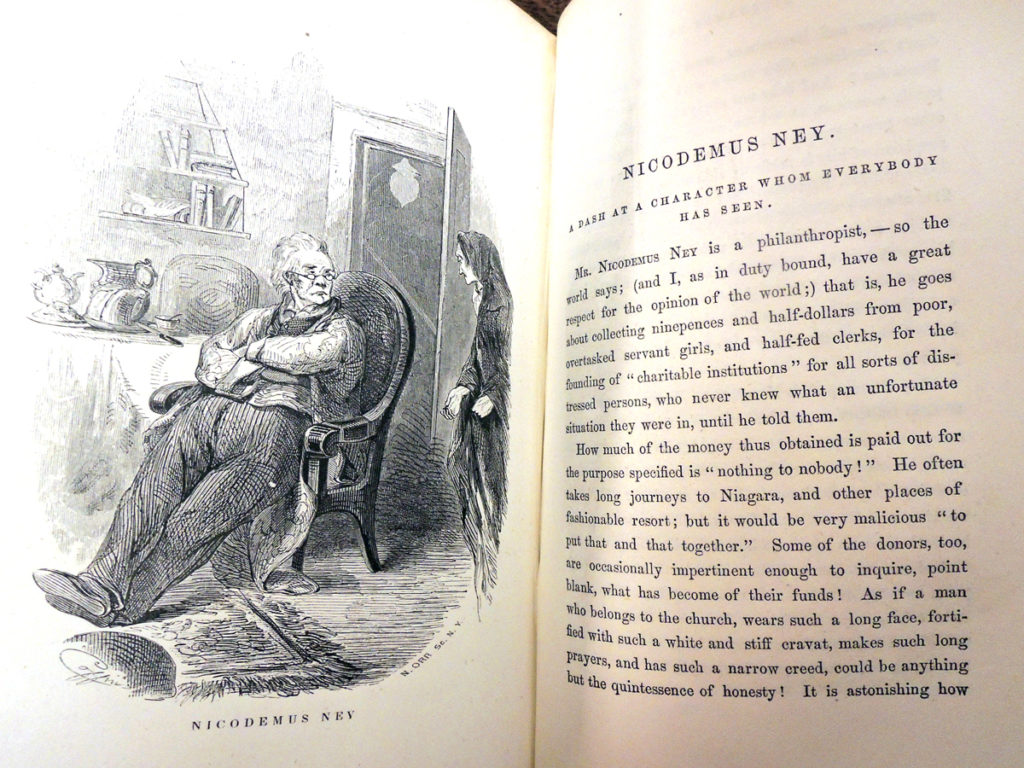

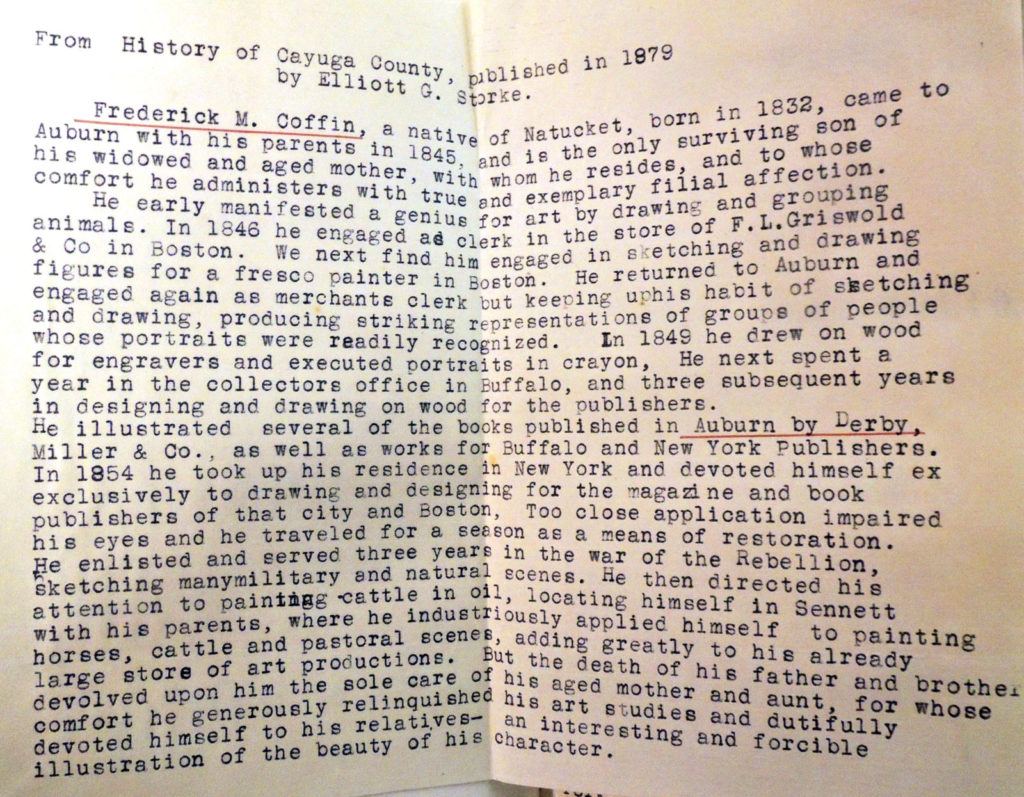

The frequent team of Frederick Coffin, designs, and Nathaniel Orr, wood engraving, were called on to illustrate this popular book. Orr was responsible for the binding.

The frequent team of Frederick Coffin, designs, and Nathaniel Orr, wood engraving, were called on to illustrate this popular book. Orr was responsible for the binding.

Robert Bonner of The New York Ledger “originally offering Fern twenty-five, then fifty, then seventy-five dollars per column, only to be turned down on all three occasions, Bonner then offered her an unprecedented $100 for each column of a serialized story, an offer which Fern finally accepted, making her the highest-paid newspaper writer in the country.”

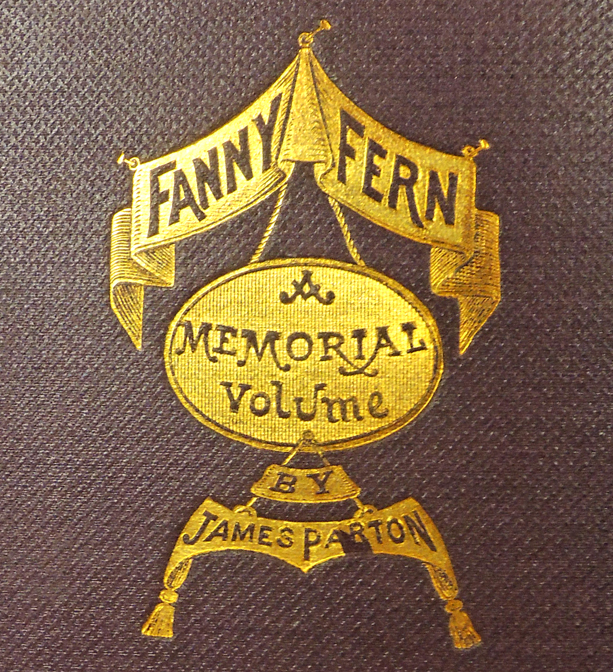

Fanny Fern (1811-1872). Fern leaves from Fanny’s port-folio : with original designs by Fred. M. Coffin [engraved by Nathaniel Orr] (Auburn: Derby and Miller, 1853). Illustrations by Frederick M. Coffin, engraved on wood by N. Orr and E. Bookhout. GAX Hamilton 1565,

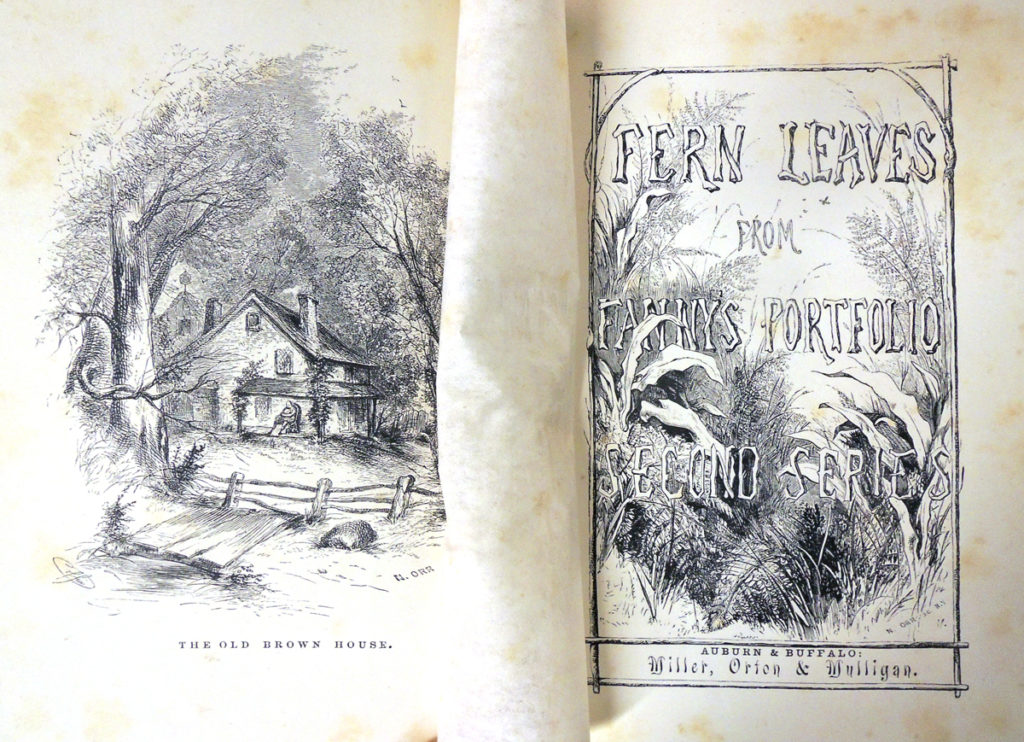

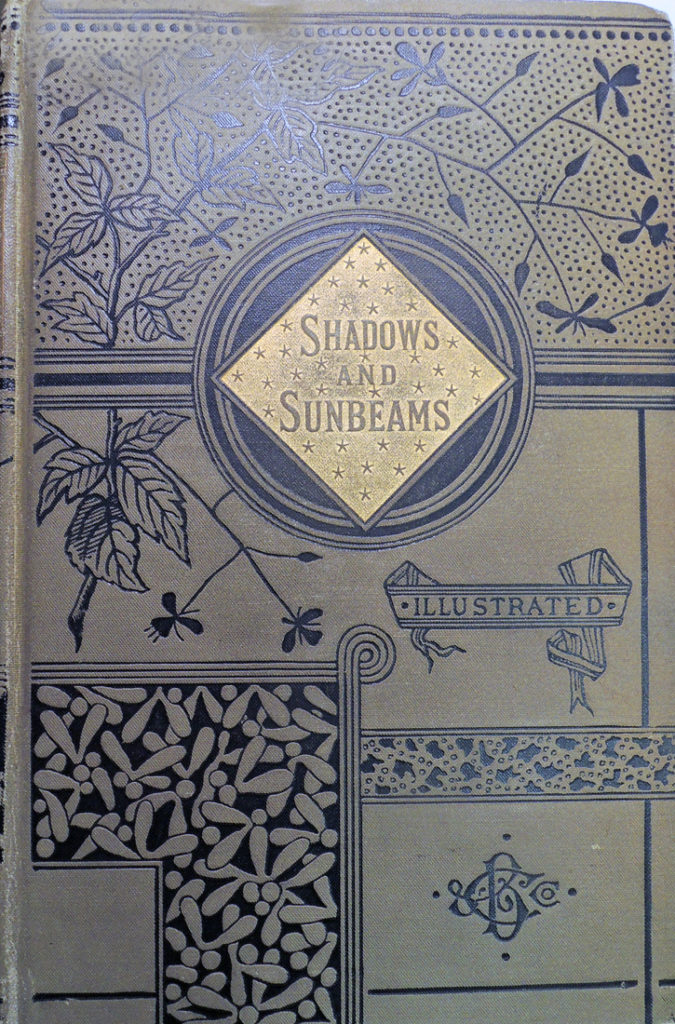

Fanny Fern (1811-1872). Fern leaves from Fanny’s port-folio Second series; with original designs by Fred. M. Coffin (Auburn [N.Y.]: Miller, Orton & Mulligan, 1854, [c1853]). Added, engr. t.p., by N. Orr. Published in London under title: “Shadows and sunbeams,” being a second series of Fern leaves from Fanny’s portfolio.

Fanny Fern (1811-1872). Fern leaves from Fanny’s port-folio : second series / with original designs by Fred. M. Coffin (Auburn ; Buffalo : Miller, Orton & Mulligan ; London : Sampson Low, son & Co., 1854). 7 full page illustrations and half title cut by F. Coffin, engraved on wood by N. Orr. Graphic Arts Collection (GAX) Hamilton 501

Mrs. Sara Payson (Wilis) Parton (1811-1872), Fern leaves from Fanny’s port-folio. (Auburn, Derby and Miller; Buffalo, Derby, Orton and Mulligan [etc.,etc.] 1853). Miriam Y. Holden Coll. (Holden). Firestone PS2523.P9F3 1853a

Fanny Fern (1811-1872), Shadows and sunbeams and other stories: being the second series of Fern leaves from Fanny’s port-folio (Chicago: Belford, Clarke & Co., 1884). RECAP 3885.05.385

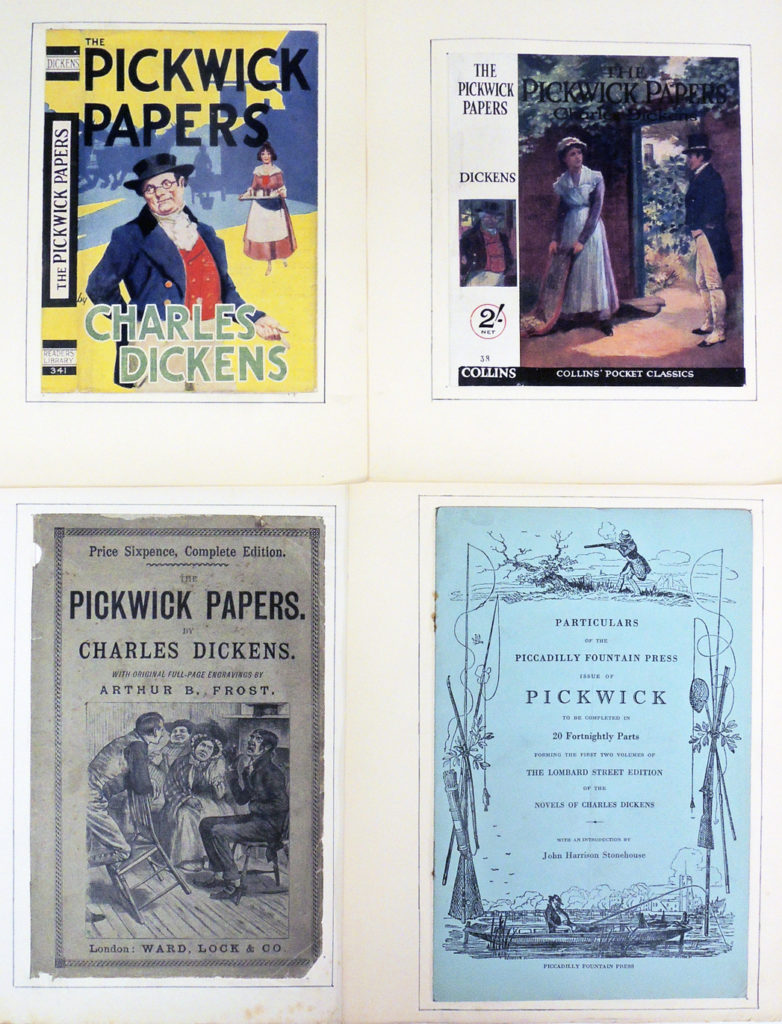

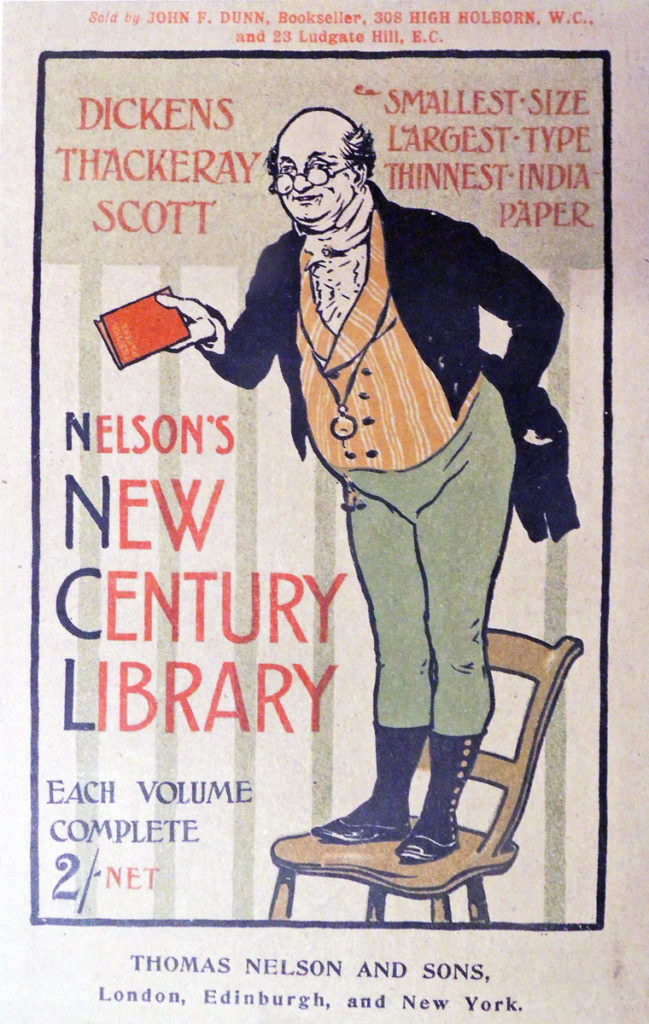

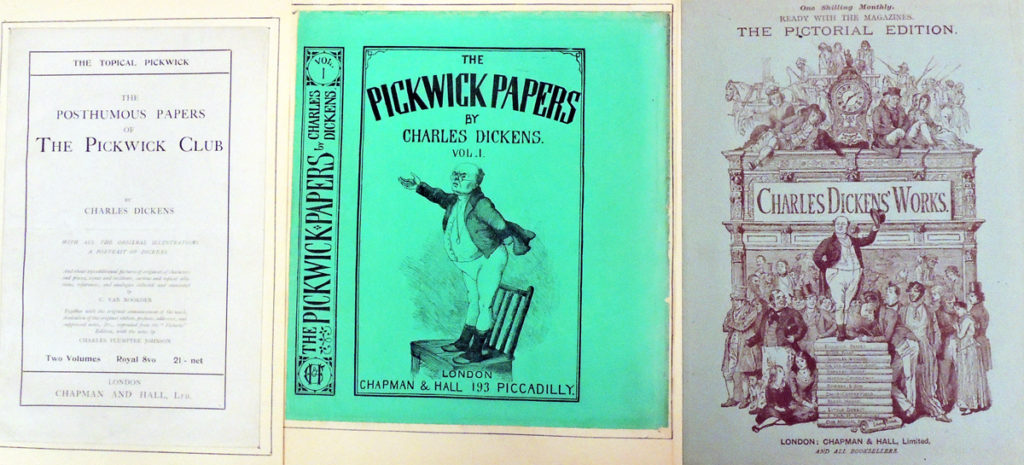

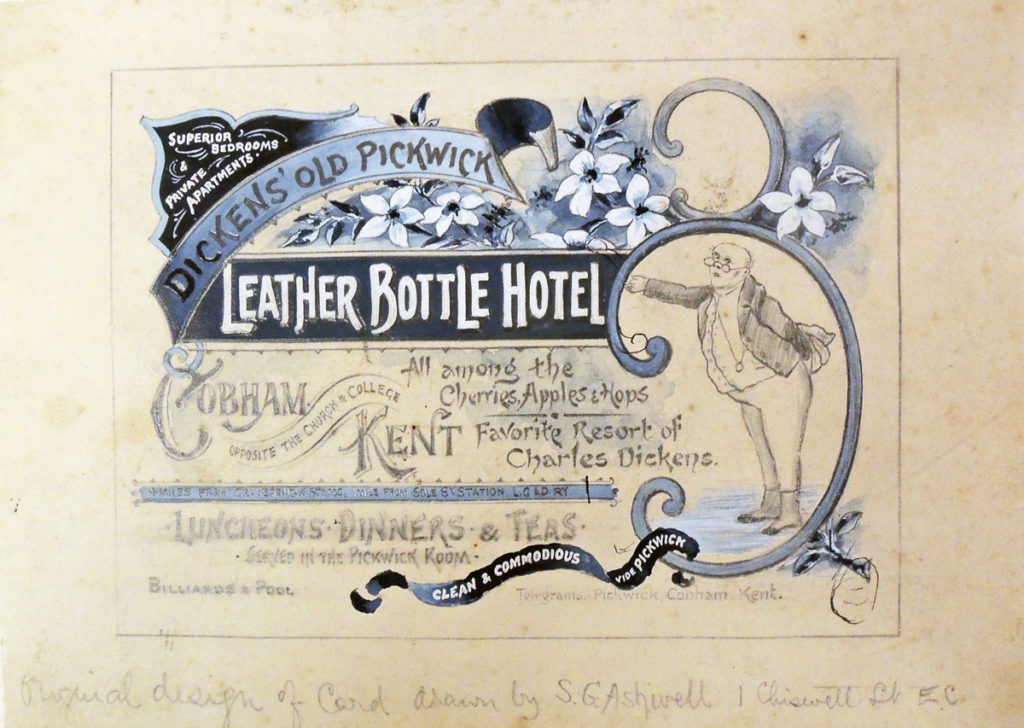

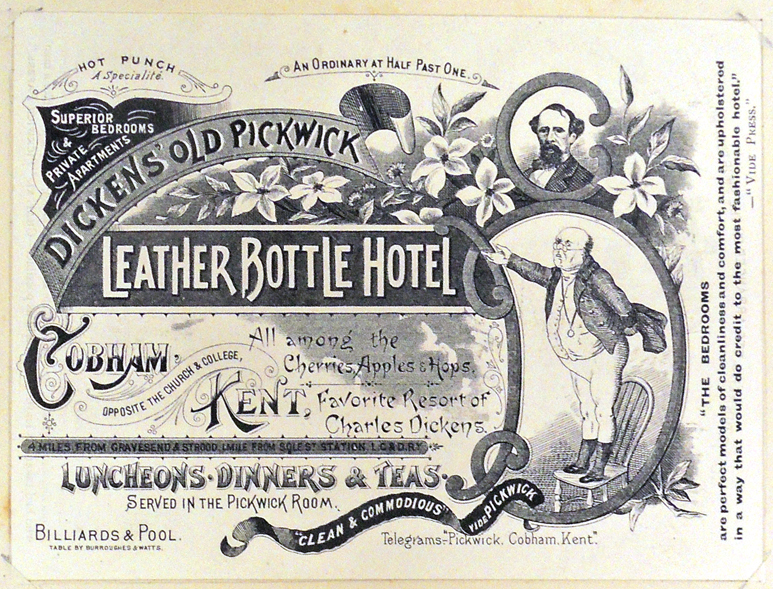

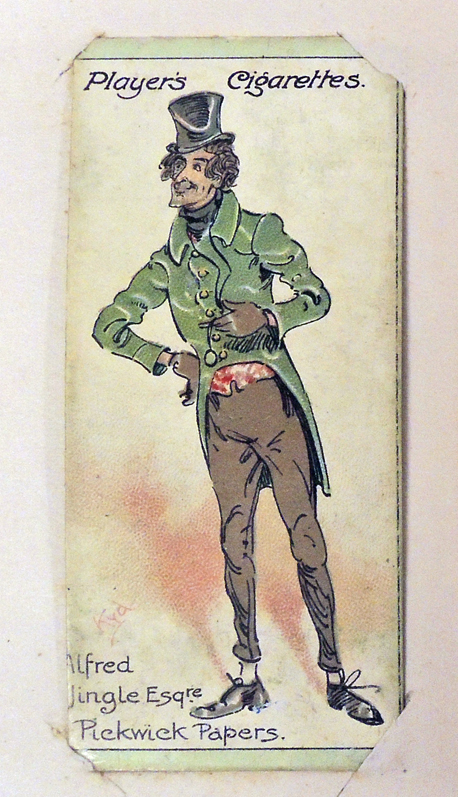

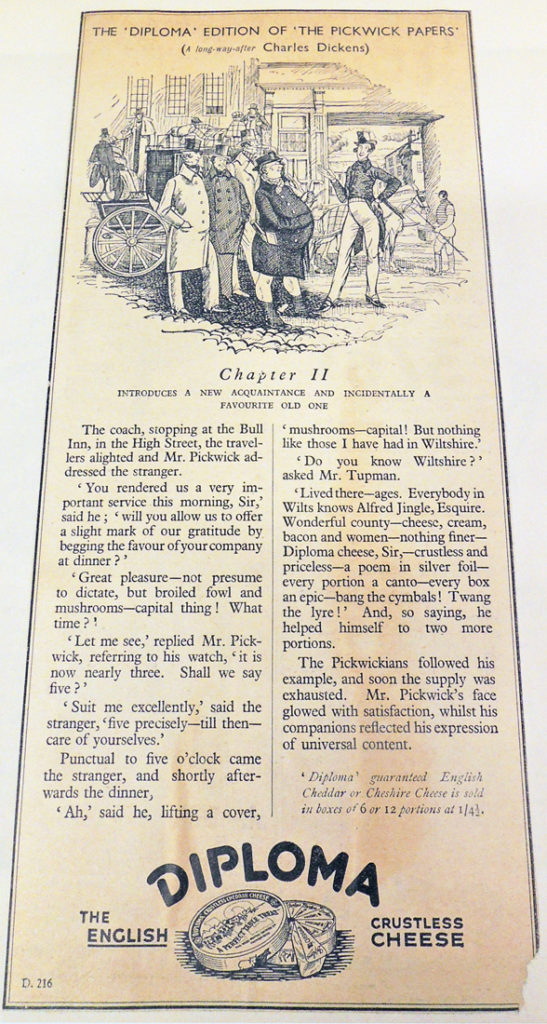

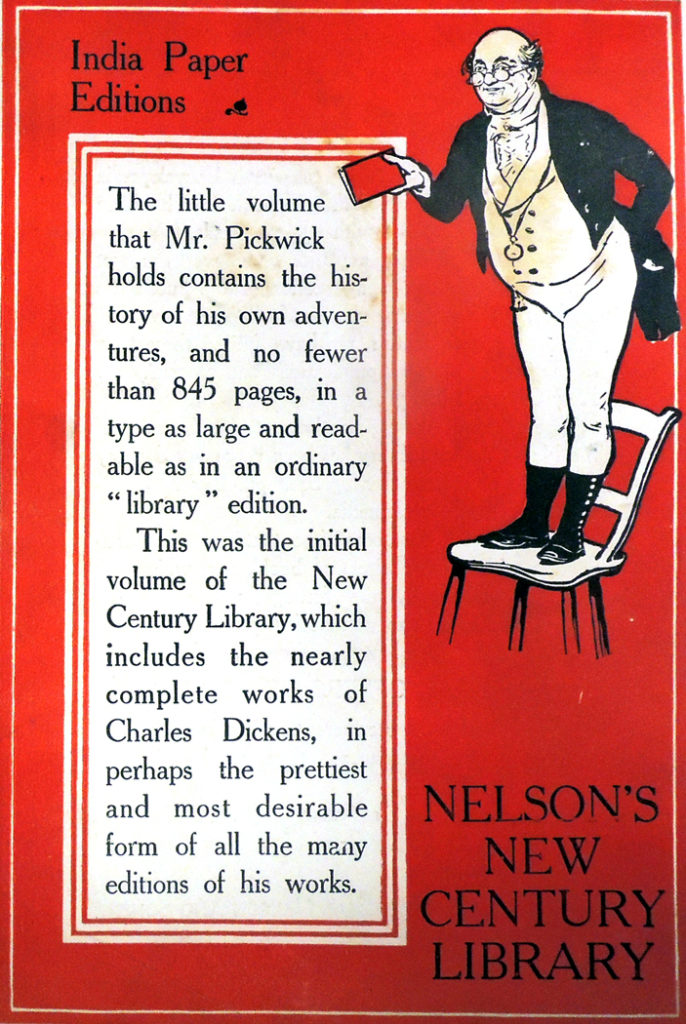

Pickwick Papers Iconography

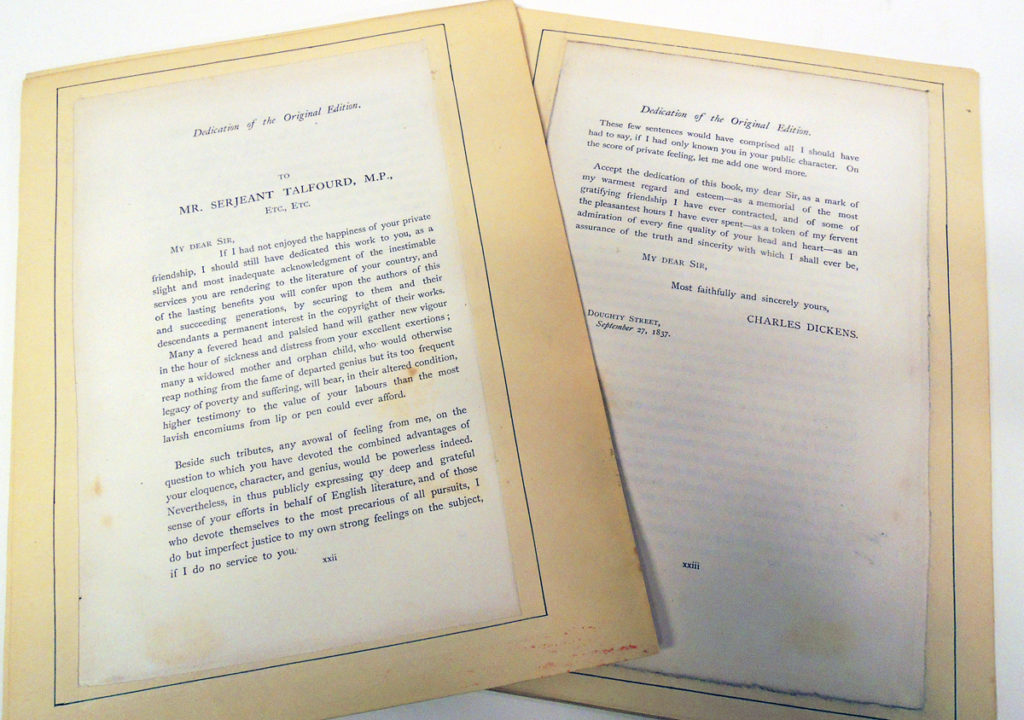

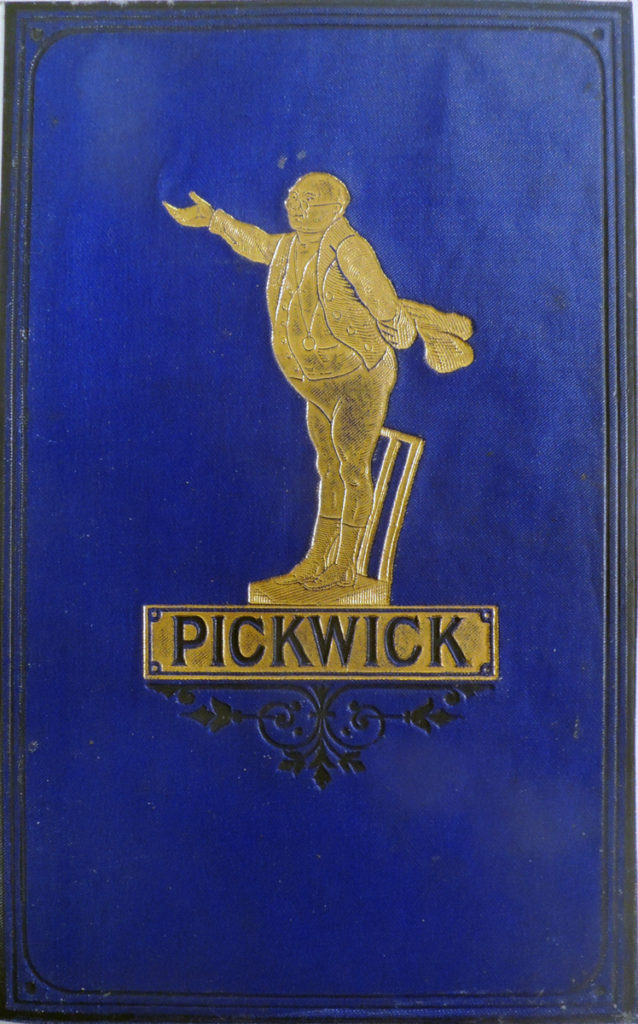

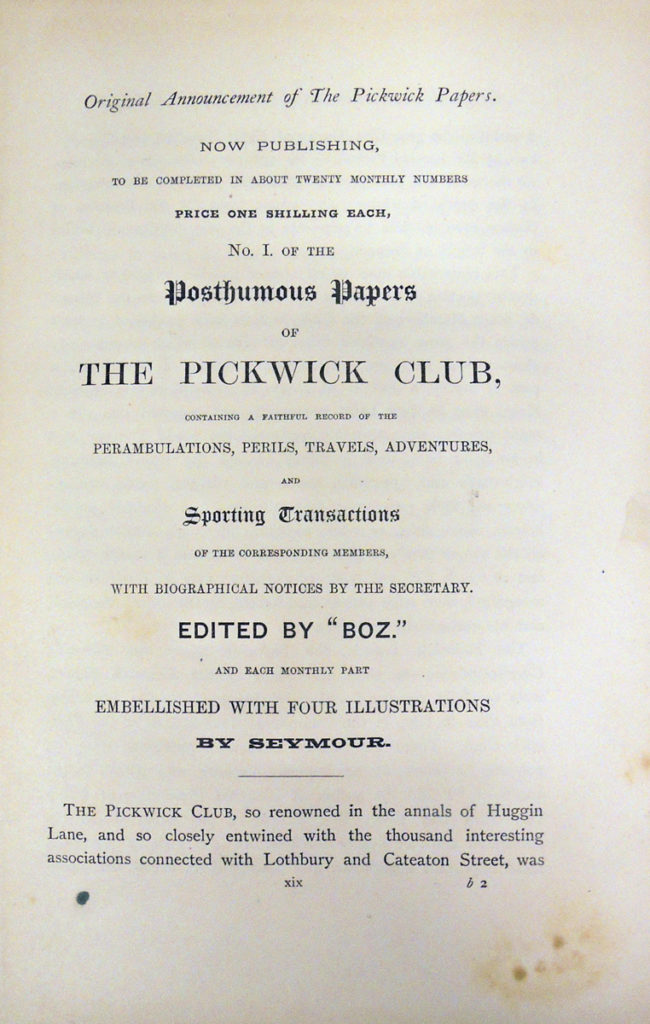

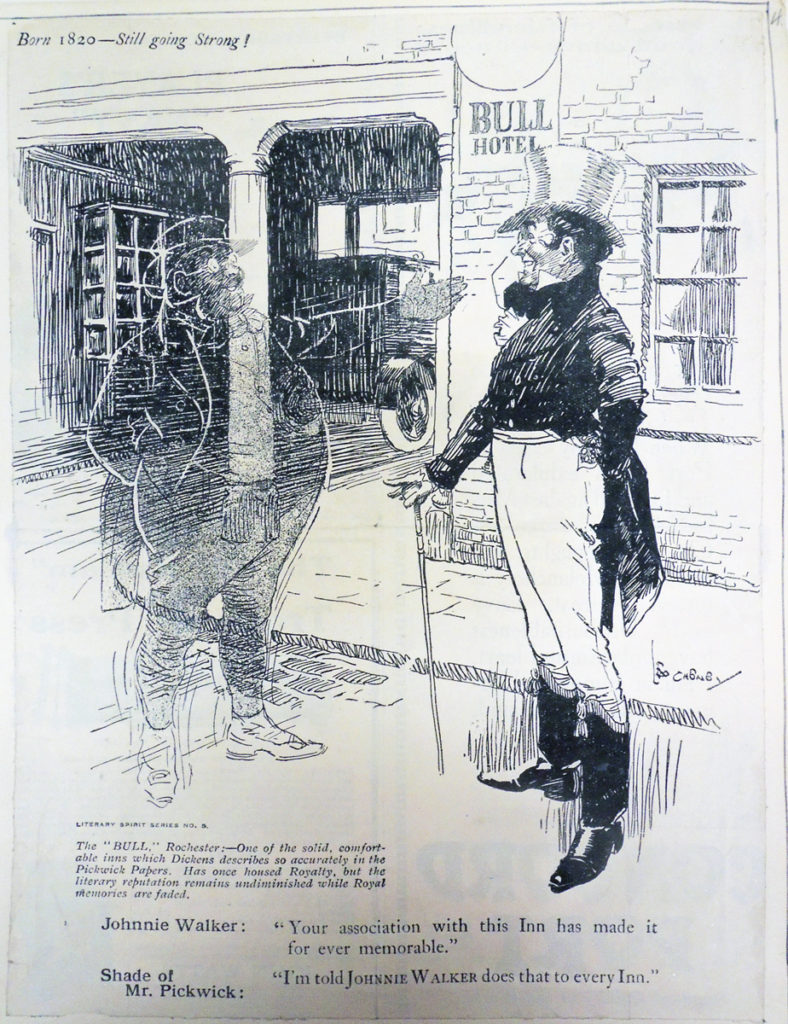

The image of Samuel Pickwick, the protagonist of The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club, drawn and etched by Robert Seymour (1798-1836) had an immediate and lasting impact, reaching beyond the pages of Dickens’ novel. Seymour committed suicide shortly after the creation of this character and the iconography of the series—19 issues over 20 months between March 1836 and October 1837—went through several visual adaptations before it was completed. As new editions continued to appear, variant designs were used to present the words to the reading public, although none has yet to improve on Seymour’s original character.

No one understood the power of the visual image better than the advertising executive Samuel William Meek (1895-1981), Vice President at the J. Walter Thompson Company, who along with his wife Priscilla Mitchell Meek (1899-1999), collected Dickens. Mr. Meek helped build a worldwide advertising empire for the Thompson Company while manager of Thompson’s London office. He handled campaigns for the General Motors Corporation, Pan American World Airways, and Reader’s Digest among many others.

Meek assembled a collection of Pickwick iconography, including a unique binding proof, title pages, advertising designs, and subsequent promotional use of the Pickwick figures outside the world of literature. Thanks to the discerning eye of our generous donor Bruce Willsie, Class of 1986, two volumes of this valuable material have come to the Graphic Arts Collection. Here is a quick list (Pickwick Papers iconography ) and are a few samples:

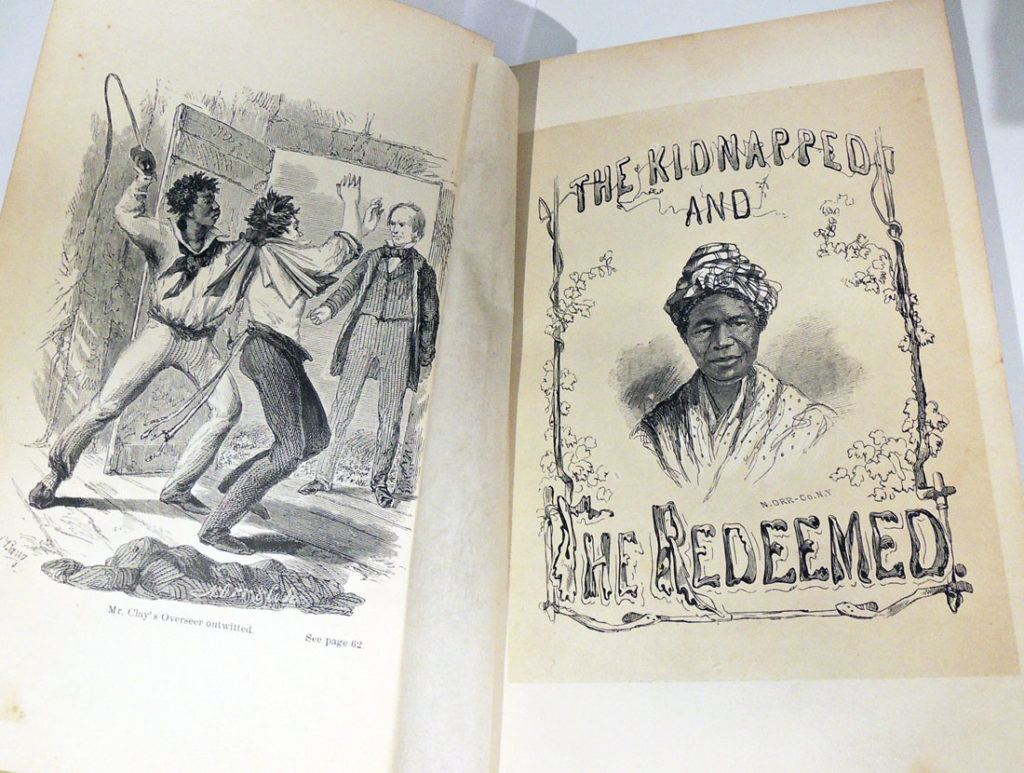

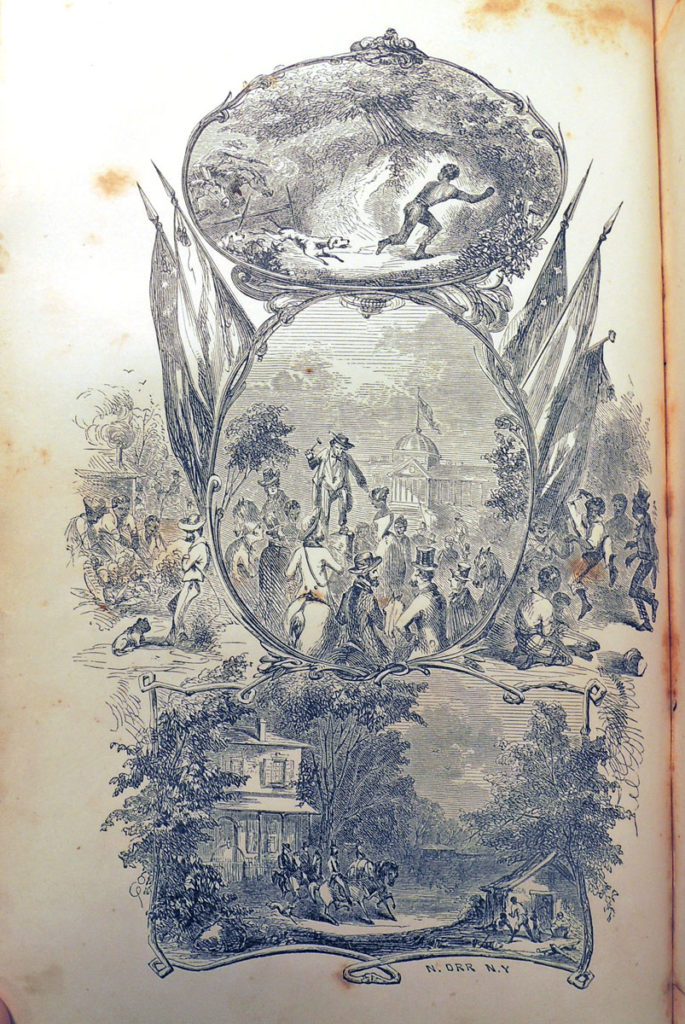

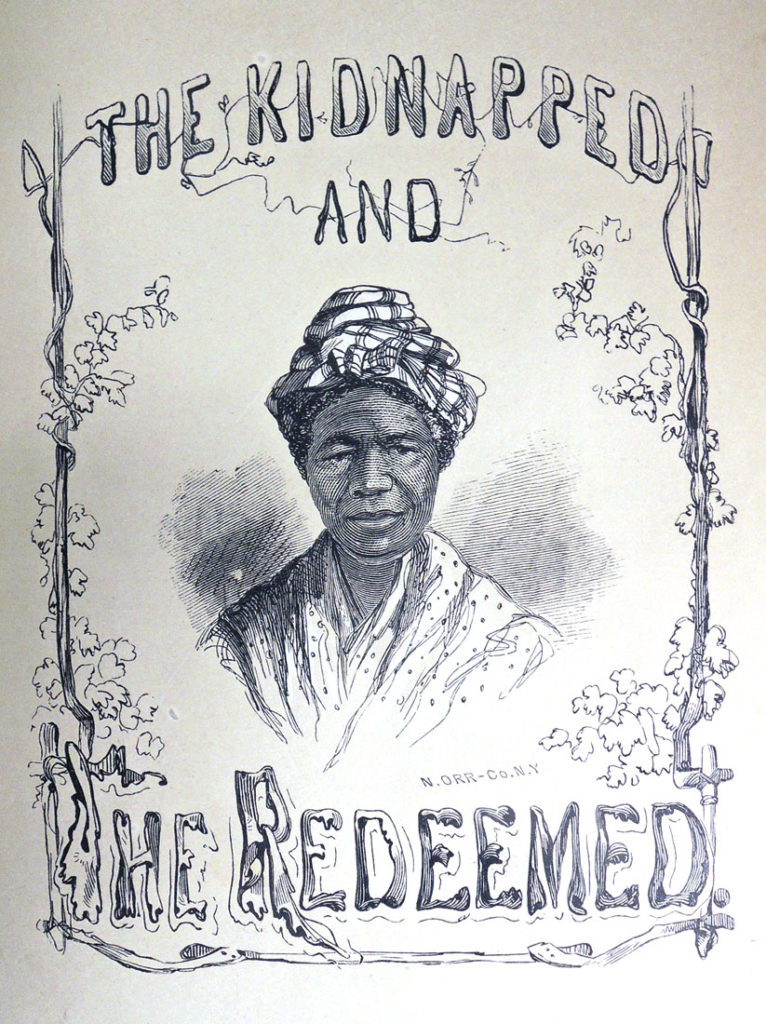

The Kidnapped and the Ransomed

A great deal of research has been done on the book-length slave narratives published in the 1840s and 1850s. See in particular the chronology at http://docsouth.unc.edu/neh/chronbio.html#1850.

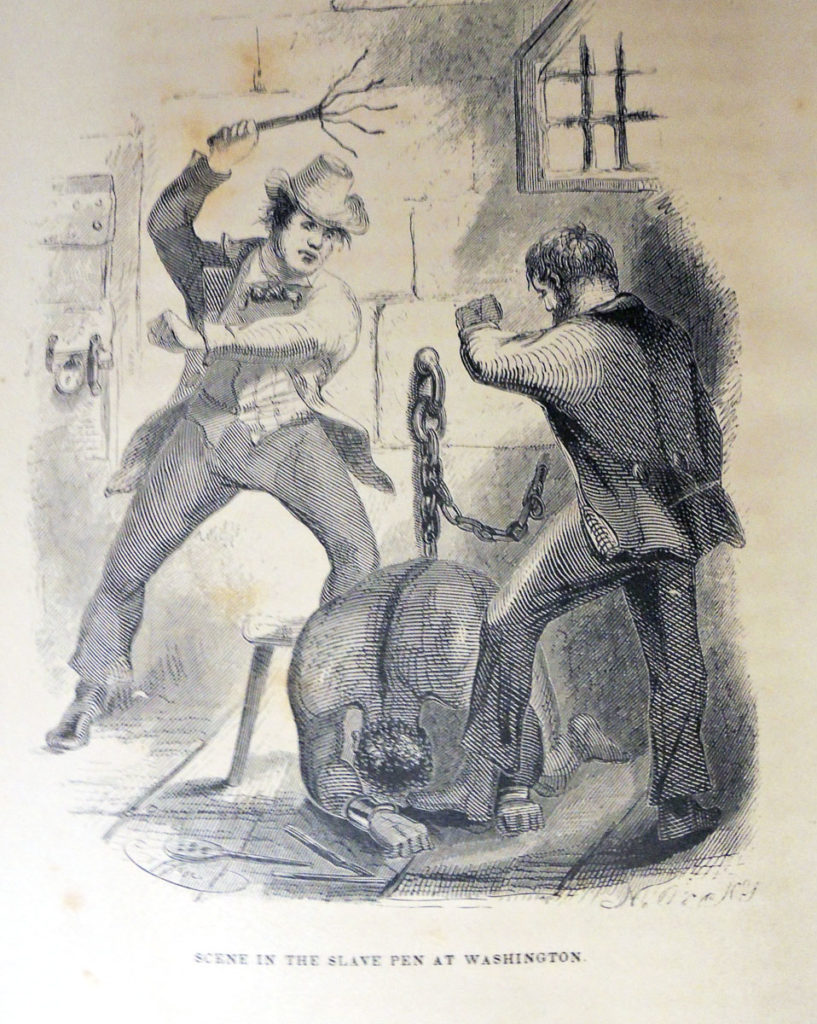

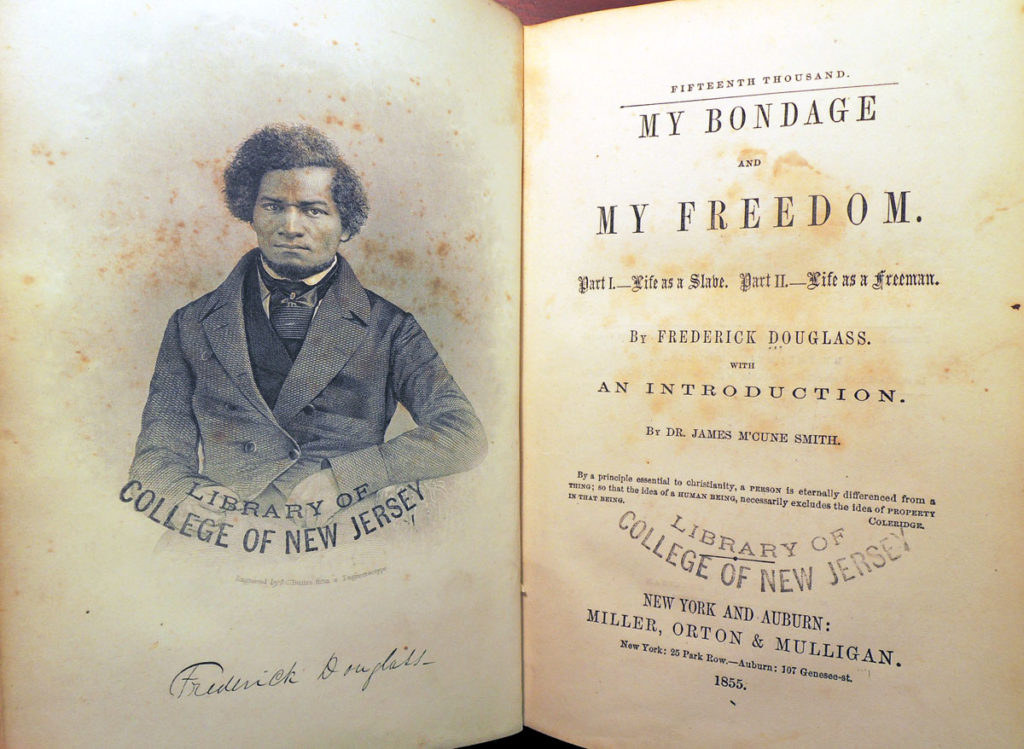

Yet few sources note that many, if not most, of the volumes are illustrated with plates engraved by Nathaniel Orr (1822-1908) and his firm at 52 John Street. Even after Orr moved to New York City in 1843, he maintained contact with the upstate New York publishing firm of Derby and Miller (later Miller, Orton, and Mulligan), “the largest miscellaneous book publishers of any in the State out of the city of New York.” Orr was their preferred wood engraver, only going to others when Orr was too busy to take on additional work.

Despite the success of these books, each selling thousands of copies, the bulk of Orr’s correspondence during these years are letters begging the publishers for payment. The work was always completed and returned to each firm along with an invoice, which often went months before the bank deposit was made. Pledges to do better were often effusive, such as Thurber W. Brown’s letter in 1851 responded to Orr’s request for money. “Your note came to hand this evening [concerning] bills . . . When you dread bankruptcy, send me by telegraph and if I owe you anything I will pledge my clothes for your benefit and come to New York on foot to bring the money.” (George A. Smathers Libraries, University of Florida).

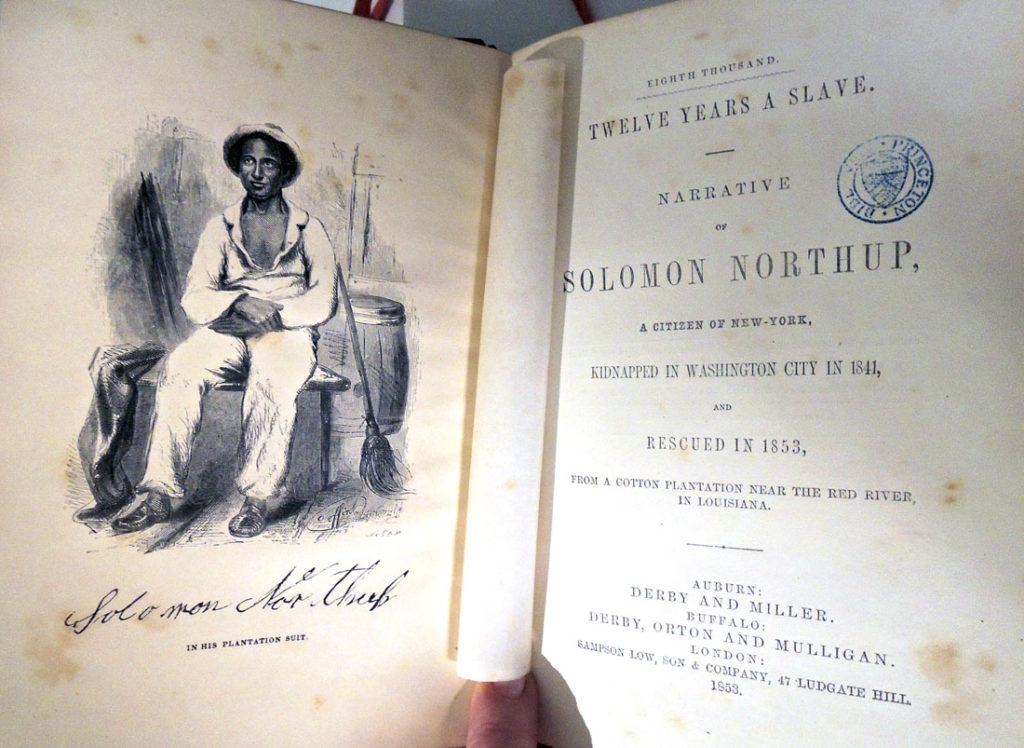

Solomon Northup (1808-1863?), Twelve Years a Slave: Narrative of Solomon Northup, a Citizen of New-York, Kidnapped in Washington City in 1841, and Rescued in 1853, from a Cotton Plantation Near the Red River in Louisiana (London: S. Low, Son & Co.; Auburn: Derby & Miller, 1853). Rare Books: John Shaw Pierson Civil War Collection (W) W91.687

Solomon Northup (1808-1863?), Twelve Years a Slave: Narrative of Solomon Northup, a Citizen of New-York, Kidnapped in Washington City in 1841, and Rescued in 1853, from a Cotton Plantation Near the Red River in Louisiana (London: S. Low, Son & Co.; Auburn: Derby & Miller, 1853). Rare Books: John Shaw Pierson Civil War Collection (W) W91.687

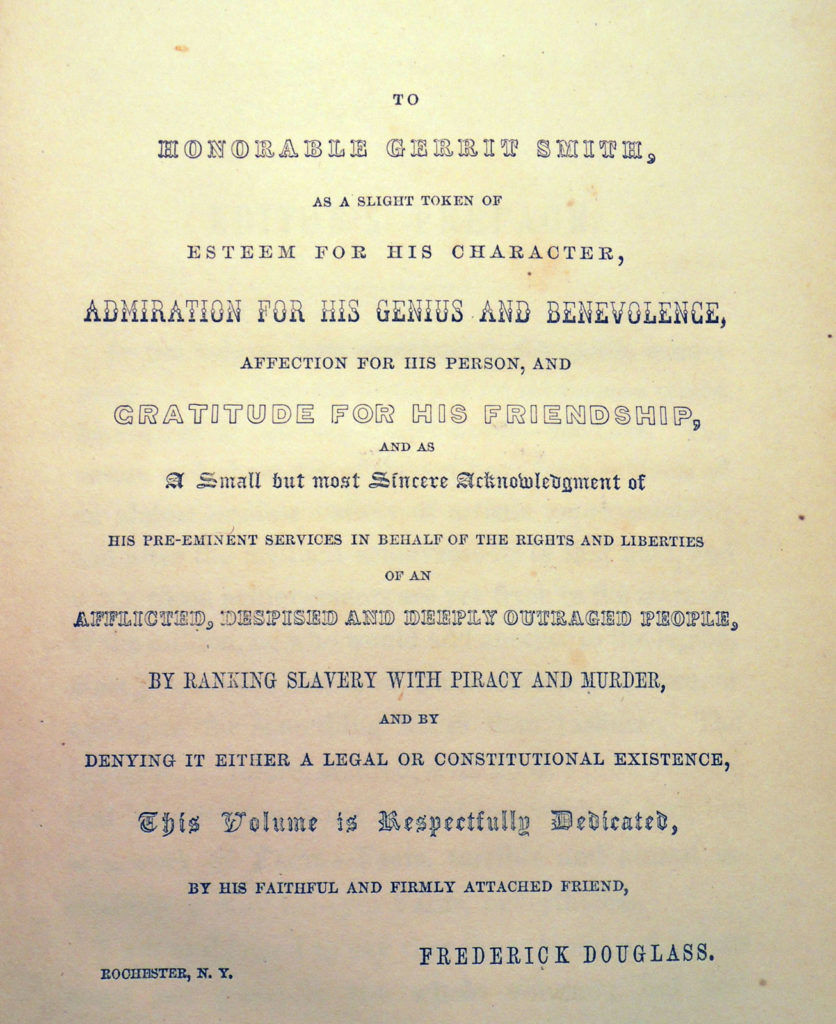

Frederick Douglass (1818-1895), My Bondage and My Freedom … With an introduction by Dr. James M’Cune Smith (New York: Miller, Orton & Mulligan, 1855). Rare Books: John Shaw Pierson Civil War Collection (W) W96.308.5

Kate E. R. Pickard, The Kidnapped and the Ransomed. Being the Personal Recollections of Peter Still and His Wife “Vina,” After Forty Years of Slavery, With an introd. by Rev. Samuel J. May; and an appendix by William H. Furness, D.D. (Syracuse: W. T. Hamilton; New York [etc.] Miller, Orton and Mulligan, 1856). With 3 full page illustrations by Charles A. Barry, engraved on wood by N. Orr-Co. Graphic Arts Collection (GAX) Hamilton 1489

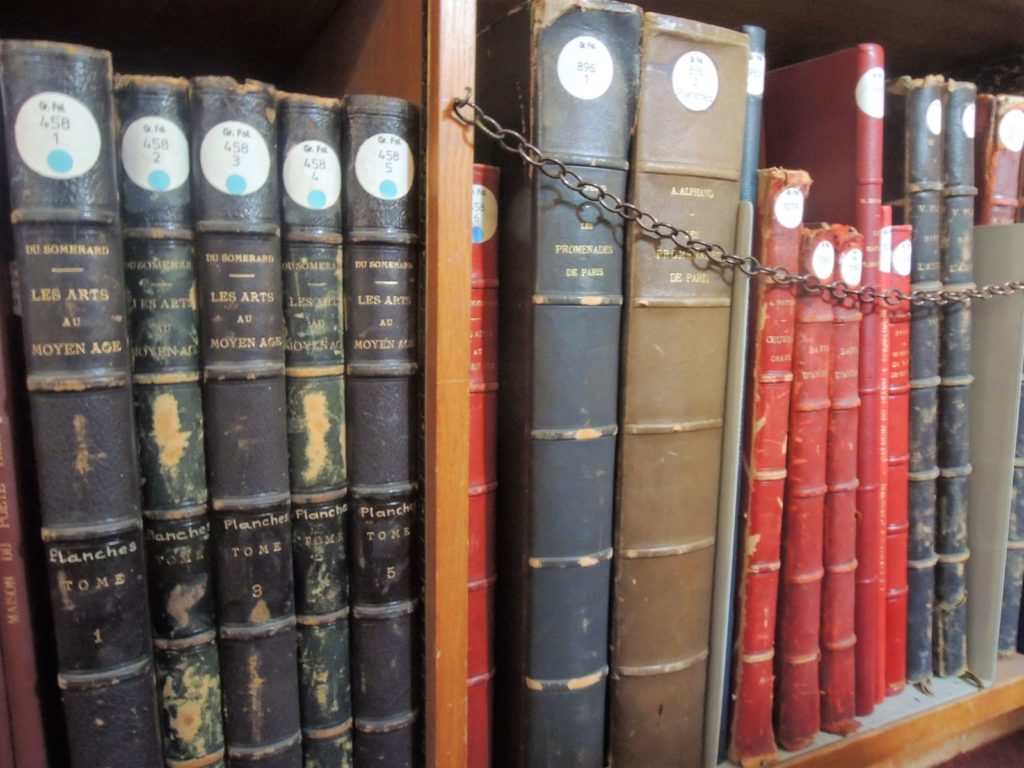

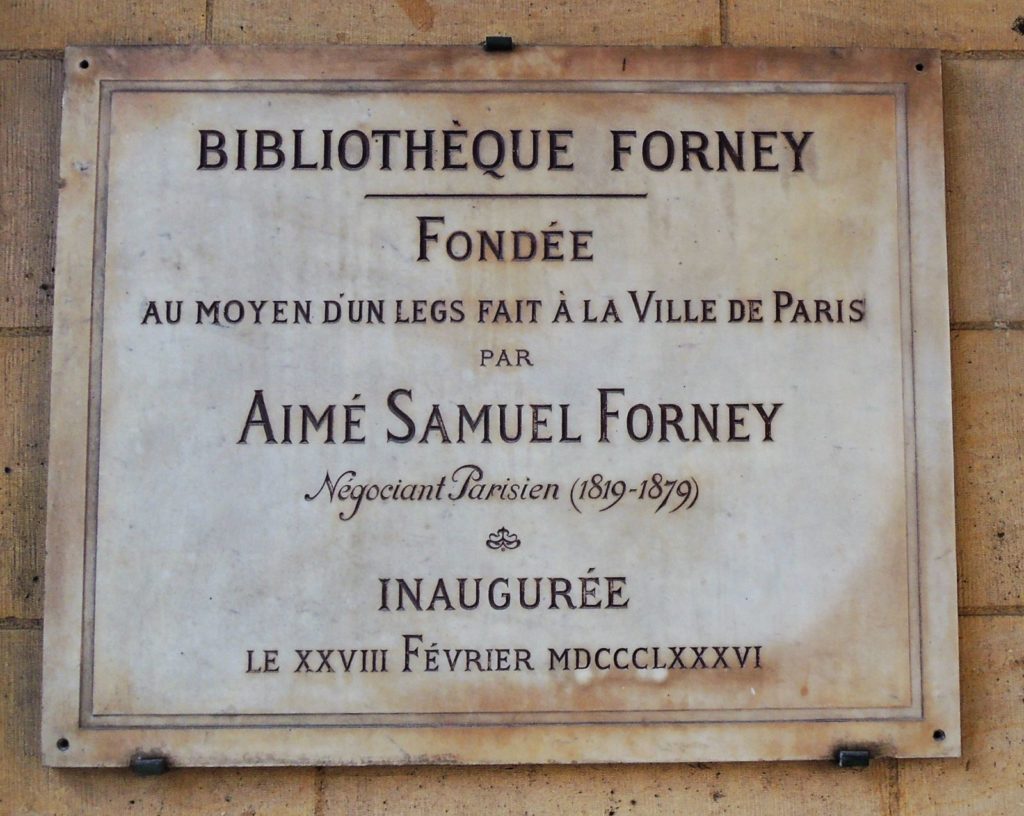

Where to study wall paper design

If you are in Paris and want to borrow an art book, one of the only options is the Bibliothèque Forney on rue du Figuier in the Marais. Inaugurated in 1886, the library bears the name of the industrialist Samuel-Aimé Forney, who gave the City of Paris a legacy for the education of craftsmen. Today, it remains a free lending library.

If you are in Paris and want to borrow an art book, one of the only options is the Bibliothèque Forney on rue du Figuier in the Marais. Inaugurated in 1886, the library bears the name of the industrialist Samuel-Aimé Forney, who gave the City of Paris a legacy for the education of craftsmen. Today, it remains a free lending library.

Originally located in the heart of the Faubourg Saint-Antoine, the Forney became so successful that in 1961, it was transferred to the renovated Hotel de Sens, one of the few examples of medieval civil architecture still found in Paris. Built from 1475 to 1519 on the order of Tristan de Salazar, Archbishop of Sens, the building has had many residents over the years. In the 19th century, for instance, there was a rolling company, a laundry, a canning factory, a hair hairdresser, and so on. In 1911, the city of Paris bought the building, which was extremely dilapidated. Restoration work begun in 1929 did not end until 1961, when the library moved in.

The restoration was very sympathetic. Architectural ornaments throughout the building honor of the draftsmen, bronziers, cabinetmakers, and other craftsmen who came to work here and borrow books.

The wall paper collection at the Forney is extensive, both woodblock printed and hand painted. This case holds samples that not only show the final design but also the colors and the sequence of the woodblocks used to create that design.

Rare and modern source material is available to the general public, but to artists and artisans in particular. Workshops and demonstrations are held on a regular basis, with an exhibition gallery on the first floor.

If you can’t get to the Forney itself, you can read about it:

Jacqueline Viaux, Bibliographie du meuble: (mobilier civil français) (Paris: Société des amis de la Bibliothèque Forney, 1966). Marquand (SA) Z5995.3.F7 V5

Bibliothèque Forney. Catalogue matières: arts-décoratifs, beaux-arts, métiers, techniques (Paris: Sociéte des amis de la Bibliothèque Forney, 1970-75). Marquand (SA) Oversize Z5939 .P225q

Bibliotheque Forney. Hôtel de Sens, Bibliothèque Forney (Paris: La Bibliothèque, 19830. Marquand (SA) Z798.B54 B53 1983

Les vapeurs ou le jour des memoires

Les Arts Décoratifs has three locations in Paris, but we chose to visit the collections and documentation at 107, rue de Rivoli. Windows there offer a view of the Louvre on one side and the Eiffel tower on the other.

Les Arts Décoratifs has three locations in Paris, but we chose to visit the collections and documentation at 107, rue de Rivoli. Windows there offer a view of the Louvre on one side and the Eiffel tower on the other.

The collections of the decorative arts are among the largest in France, comprised of thousands of pieces from the various fields of the decorative and applied arts. Many new donations, purchases and bequests are added to the collections every year.

The collections of the decorative arts are among the largest in France, comprised of thousands of pieces from the various fields of the decorative and applied arts. Many new donations, purchases and bequests are added to the collections every year.

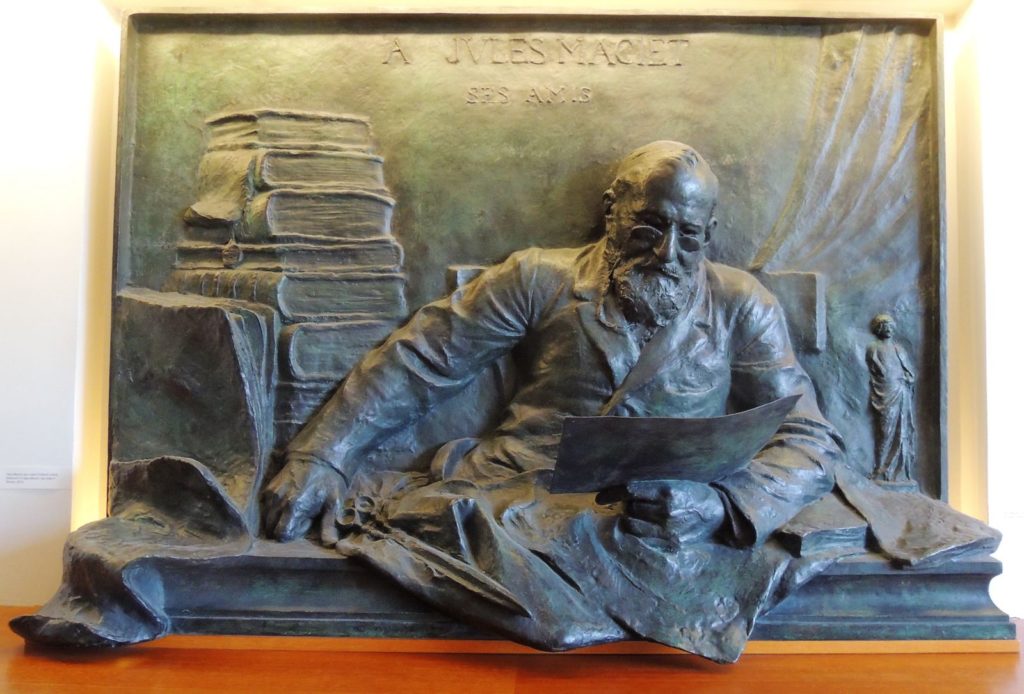

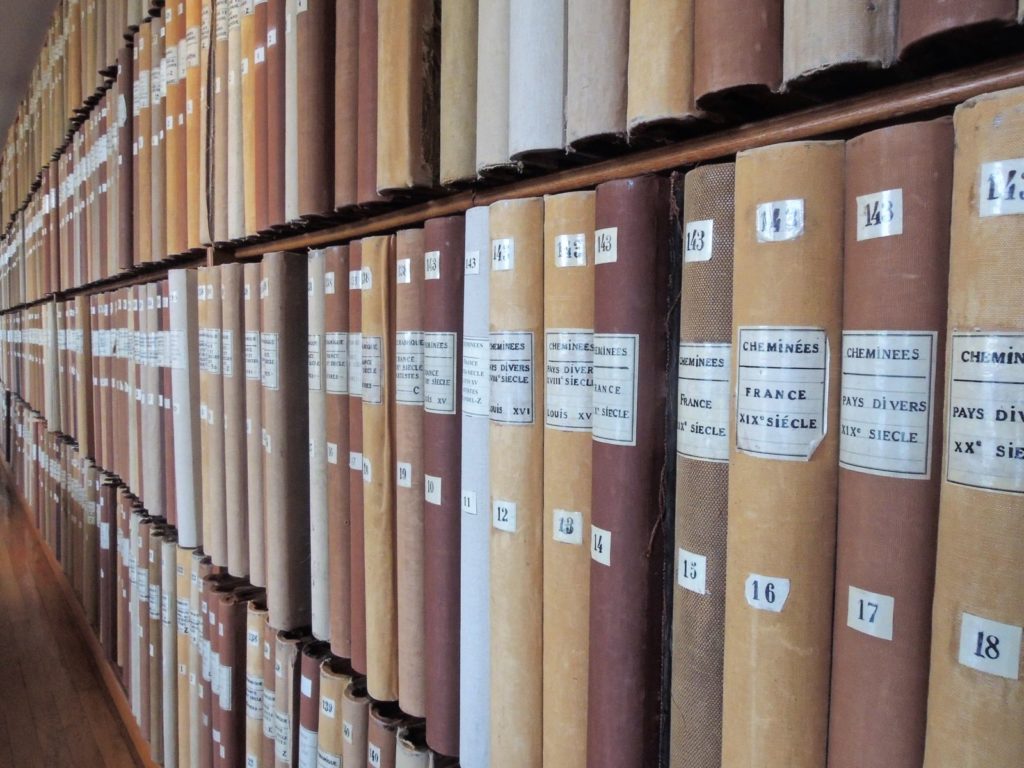

The library and documentation center house a wide range of materials including books, manuscripts, prints, engravings, photographs, archives of artists and professionals, and ephemera. Established in 1864 by the founding members of the UCAD (Union Centrale des Arts Décoratifs), it was their hope to provide artists with a store of forms and images for their inspiration. One of the most extraordinary resource is the volumes of the Maciet collection, a bound selection of reproductions and original works on paper organized by topic. In these volumes, one might find a 19th-century photograph by Henri Le Secq (1818-1882) documenting a Paris street pasted next to a printed menu of a restaurant on that street.

The organization’s documentation notes, “When art lover and collector Jules Maciet (1846-1911) crossed the threshold of the library of decorative arts in 1885, he understood that books alone could not satisfy the demands of artists and artisans: It would take images, lots of images. …Thus, from 1885 to 1911, the date of his death, Jules Maciet became an image hunter, bringing together hundreds of thousands of prints, photographs, documents from all sources from catalogs, books and magazines. He slices, sorts, and sticks them in great albums and imagines a methodical classification in the encyclopaedic spirit of the nineteenth century.”

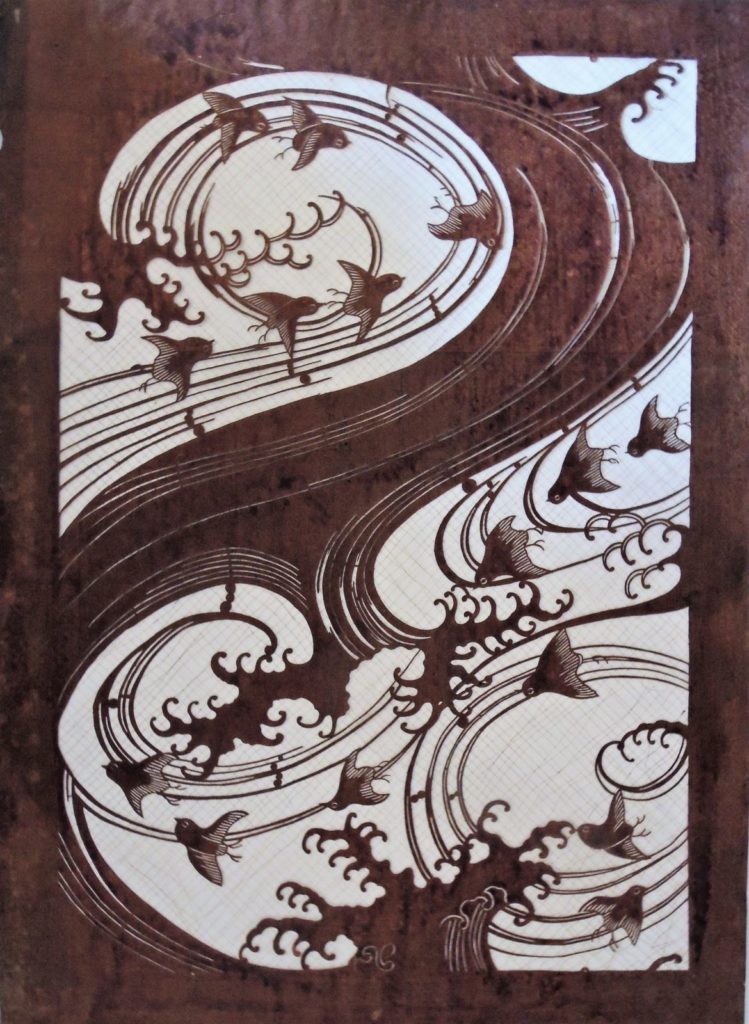

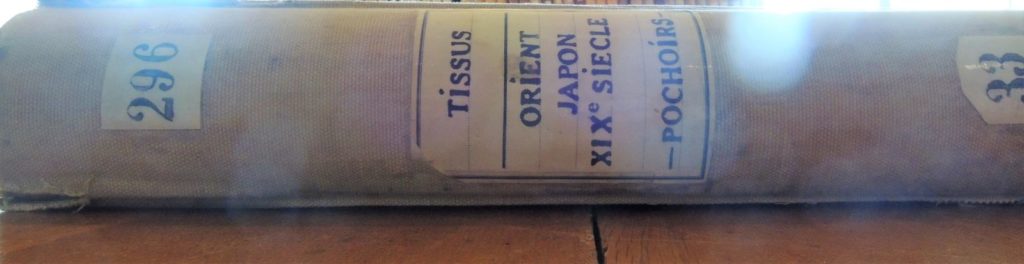

We pulled the volume on Japanese pochoir and found a complete rare book reproducing stencil color disbound and pasted in. Happily, a box of original Katagami (Japanese paper) stencils were brought out to compliment the research.

We pulled the volume on Japanese pochoir and found a complete rare book reproducing stencil color disbound and pasted in. Happily, a box of original Katagami (Japanese paper) stencils were brought out to compliment the research.

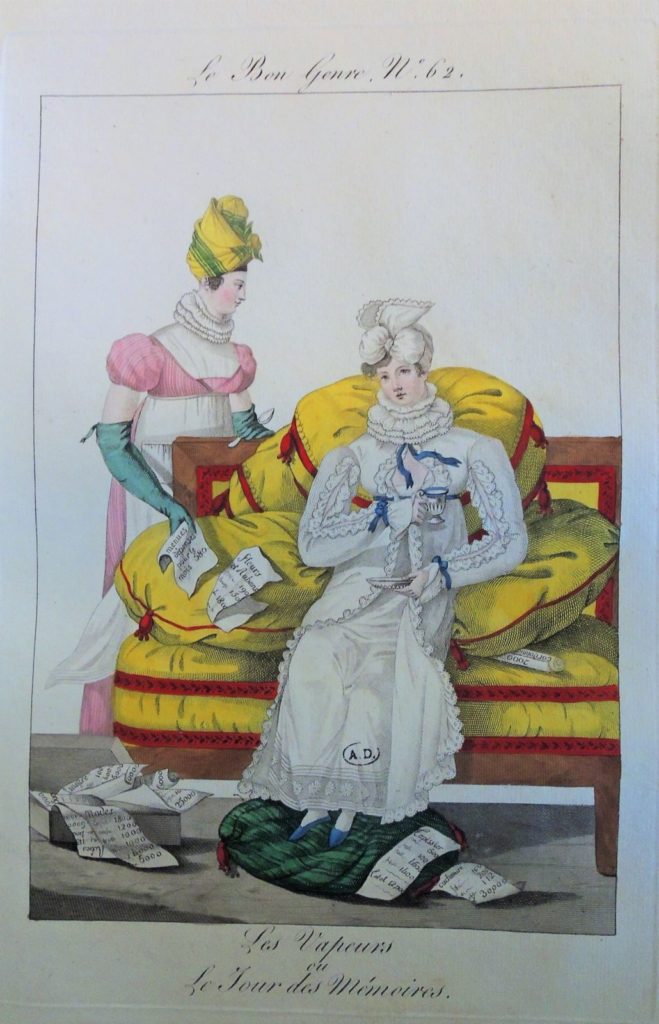

Also on the table was a stunning volume of pochoir colored caricatures from the series Le Bon Genre, which we recognized from Princeton’s Charles Rahn Fry Pochoir Collection. Here’s a plate that seems to fit the visit: “Les vapeurs ou le jour des memoires” (The Vapors or the Day of Memories).

Le Bon genre; réimpression du recueil de 1827; comprenant les “Observations…” et les 115 gravures. Préface de Leon Moussinac (Paris: Les Éditions Albert Lévy [1931]). “Les planches ont étés gravées par E. Doistau, imprimées par R. Tanburro, et coloriées par J. Saudé … Il en a été tiré 750 exemplaires”–Verso of p. preceding t.p. Princeton’s copy is no. 444, from the Charles Rahn Fry Pochoir Collection. Graphic Arts Collection (GAX) Oversize 2004-0020F

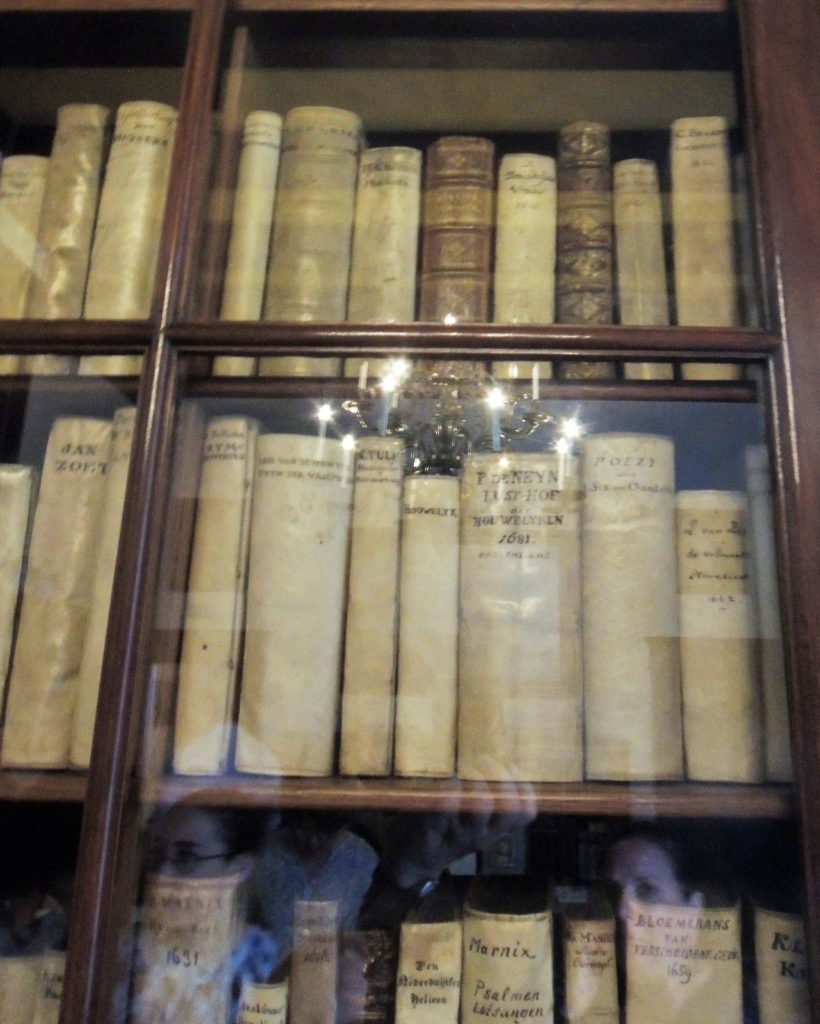

Frits Lugt’s collection

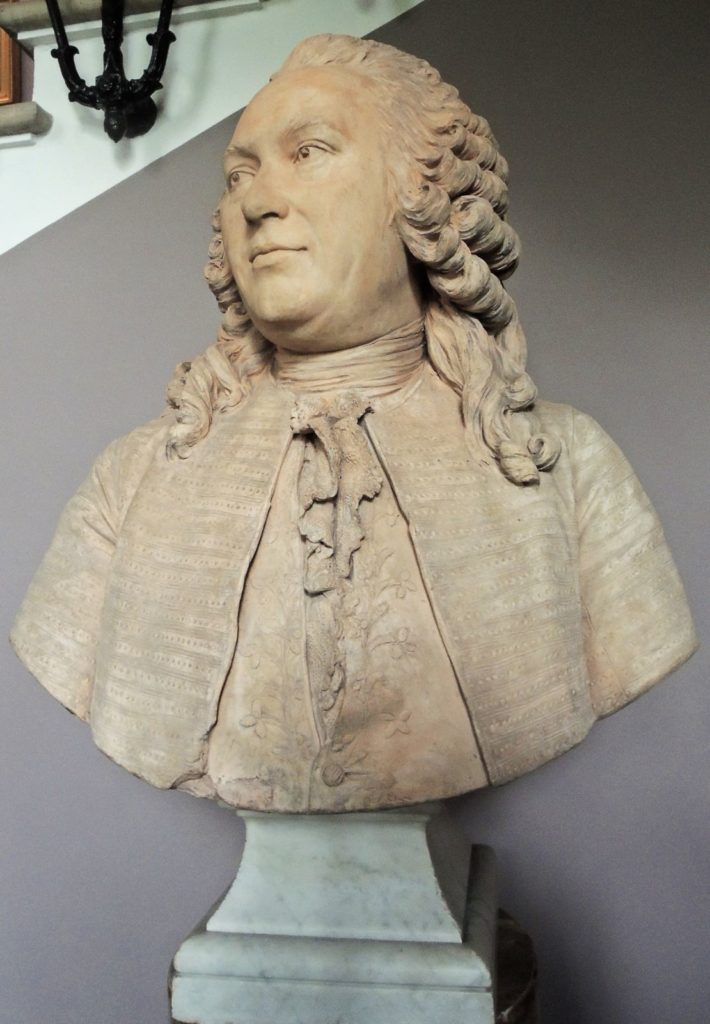

In 1947, Frits Lugt (1884-1970) established the Fondation Custodia in the historic hôtel Lévis-Mirepoix at 121 rue de Lille and endowed it with his entire of collection of paintings, drawings, prints, rare books, artists’ letters, and much more.

In 1947, Frits Lugt (1884-1970) established the Fondation Custodia in the historic hôtel Lévis-Mirepoix at 121 rue de Lille and endowed it with his entire of collection of paintings, drawings, prints, rare books, artists’ letters, and much more.

In 2015, the Terra Foundation for America Art opened a Center & Library upstairs from the Fondation, including a joint exhibition space and reading room. It appears to be a good collaboration. We were very fortunate to be allowed to tour both, including the Lugt art collection, housed in adjoining rooms in the eighteenth-century Hôtel Turgot.

Lugt, who began collecting in 1915, was a self-taught art historian and author whose books remain standard works to this day. The famous ‘L’ followed by the number Lugt assigned to sale catalogues and collector’s marks is recognized by all art historians.

Princeton University faculty and students have online access to Lugt’s Répertoire des catalogues de ventes publiques http://library.princeton.edu/resource/3932, which lists more than 100,000 art sales catalogues of the period 1600 to 1925 from libraries in Europe and the USA, both in French and in English. It can be searched on Lugt number, date, place, provenance, auction house and existing copies.

At the front door, you are greeted by a terra-cotta bust of Jacques Turgot, Baron de l’Aulne (1727-1781), which may have been sculpted by Jean-Antoine Houdon. All along the 18th-century staircase, the walls are filled with Lugt’s collection of painted landscapes.

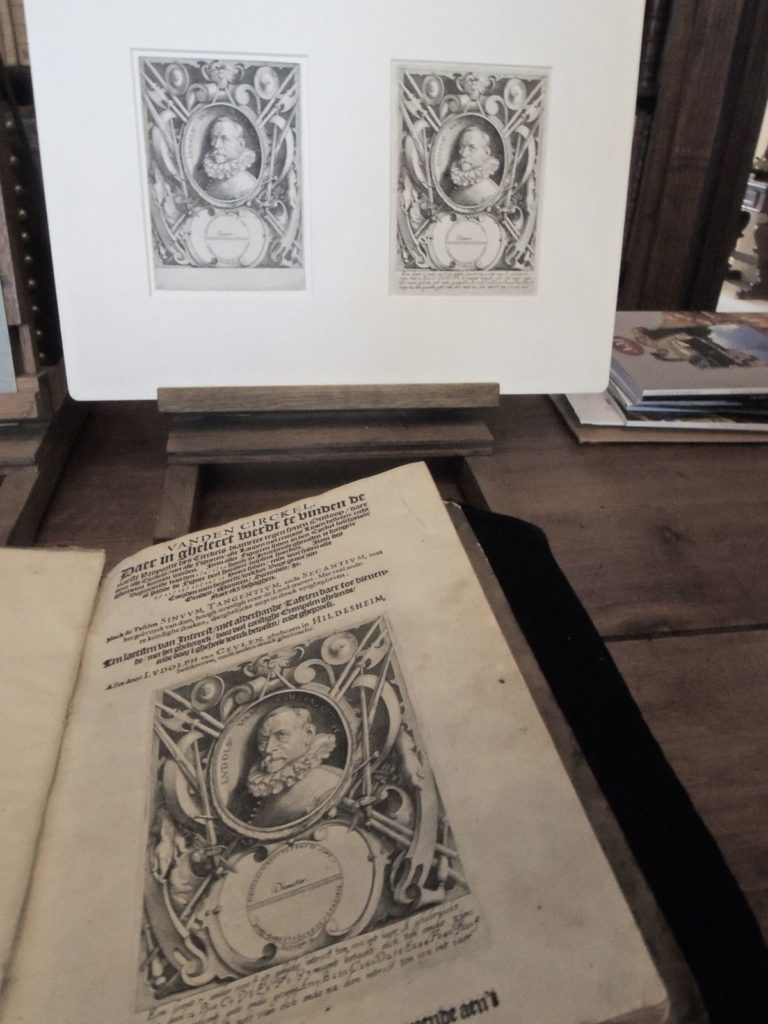

One of the treasures pulled for us was a 1596 copy of Ludolf van Ceulen (1539-1610), Van den circkel: daer in gheleert werdt te vinden de naeste proportie des circkels-diameter tegen synen omloop, with a portrait of the author on the title page, engraved by Jacques de Gheyn II (1565-1629). Lugt also acquired a proof without lettering and a rare variant. See all three below.

“In the late sixteenth century, especially in the Netherlands, there was a revival of interest in the works of Archimedes. Van Ceulen was a part of this Archimedean renaissance, and early in his career, he read a translation of Archimedes’ treatise, Measuring the Circle. In this work, Archimedes estimated the value of pi by calculating the circumferences of polygons that just fit inside and outside the circle, reasoning (correctly) that the circumference of the circle must lie between those two values. Using polygons of up to 128 sides, Archimedes found that pi must lie between (using modern notation) 3.141 and 3.142. Van Ceulen found a way to increase the number of sides of the inscribed polygons from 128 to well into the millions, and he initially found a value of pi accurate to 20 decimal places. This number was engraved just below his portrait on the title page of his first book, Van den Circkel (1596).”

Musée du quai Branly

The Musée du quai Branly holds almost 370,000 works of art and 700,000 iconographical images (photographs) originating in Africa, the Near East, Asia, Oceania and the Americas. The work is considered for its aesthetic value, not its ethnographic appeal (that work is currently at the Musée de l’Homme). The walk up to the front door is made through a dense forest of trees and grasses, with the Eiffel Tower seen around the corner of the building.

The Jacques Kerchache Reading Room on the top floor of the museum holds over 100 researchers at one time, tempting them with a view as far as the Sacré-Cœur Basilica. Public spaces throughout the building are decorated with pieces from the museum collection.

The collection offers examples of printing and drawing on many different surfaces, including this piece of Masi or Tapa cloth from the Bismarck archipelago, off New Guinea in the southwest Pacific Ocean. The work of art was made in the early twentieth century and is shown in comparison with Pablo Picasso’s painting made around the same time.

“Generally, to make bark cloth, a woman would harvest the inner bark of the paper mulberry (a flowering tree). The inner bark is then pounded flat, with a wooden beater or ike, on an anvil, usually made of wood. In Eastern Polynesia (Hawai’i), bark cloth was created with a felting technique and designs were pounded into the cloth with a carved beater. In Samoa, designs were sometimes stained or rubbed on with wooden or fiber design tablets. In Hawai’i patterns could be applied with stamps made out of bamboo, whereas stencils of banana leaves or other suitable materials were used in Fiji. Bark cloth can also be undecorated, hand decorated, or smoked as is seen in Fiji. Design illustrations involved geometric motifs in an overall ordered and abstract patterns.”–Dr. Caroline Klarr

See an example: Sara Featherstone Robinson, Hina-Malama, moon-goddess of the Polynesian Islands: a tapa story woven from ravelings of old Polynesian myths and chants (Berkeley, Calif. [1926]). Binding note: Illus tapa cloth wrap. Brown title and illus. Cotsen Children’s Library (CTSN) Pams / Eng 20 / Box 37 31533

The Art of Noises in a silent gallery

There is nothing so wonderful as having a museum to yourself.

There is nothing so wonderful as having a museum to yourself.

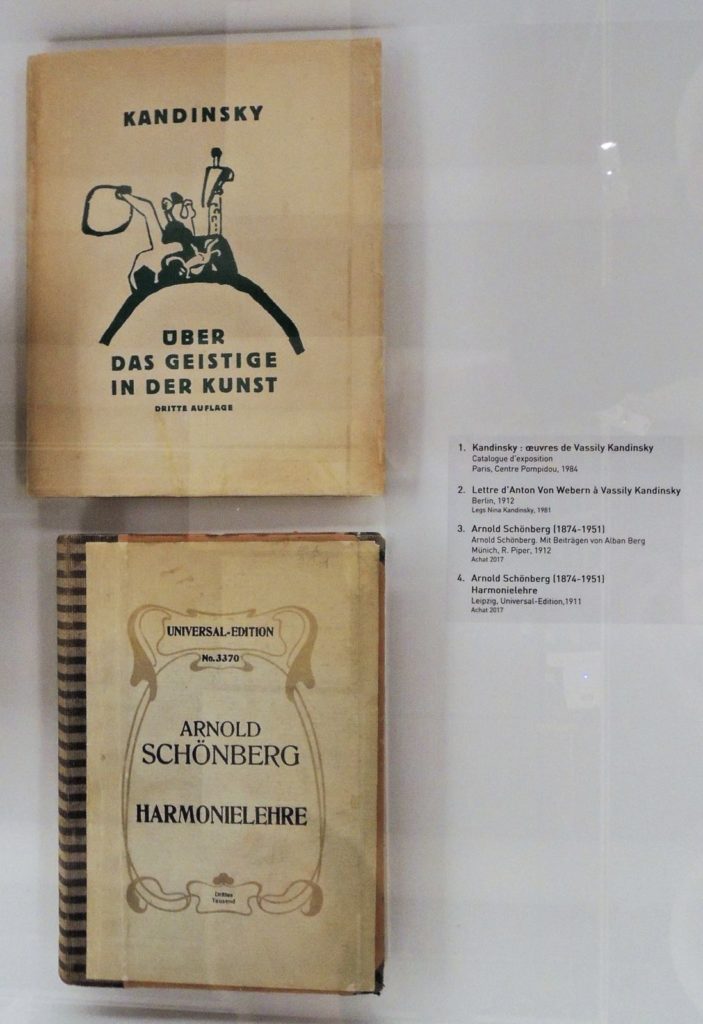

Colleagues in the Kandinsky Library at the Georges Pompidou Center, also known as the Musée National d’Art Moderne (MNAM), not only welcomed a few visitors by pulling treasures from their vaults but also led a tour of the stunning, newly hung galleries of the museum’s permanent collection.

Colleagues in the Kandinsky Library at the Georges Pompidou Center, also known as the Musée National d’Art Moderne (MNAM), not only welcomed a few visitors by pulling treasures from their vaults but also led a tour of the stunning, newly hung galleries of the museum’s permanent collection.

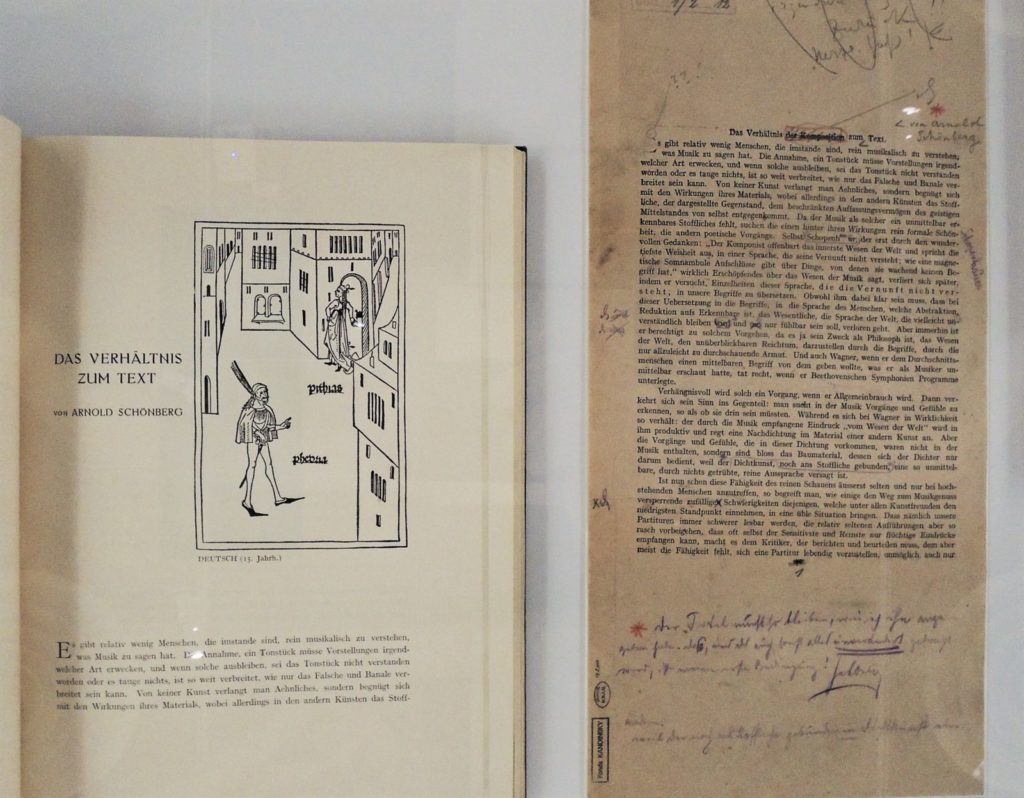

One feature of the museum’s new interpretation of their collection are the works on paper interspersed throughout, this year highlighting the relationship between art and music in the 1900s.

Paintings, books, sound, and documents are intertwined in cases and on the wall, such as the work of Arnold Schönberg (1874-1951), who was both a painter and a composer, and that of painter and philosopher Wassily Kandinsky (1866-1944).

Their books are seen side by side, with the proofs marked up by Schönberg.

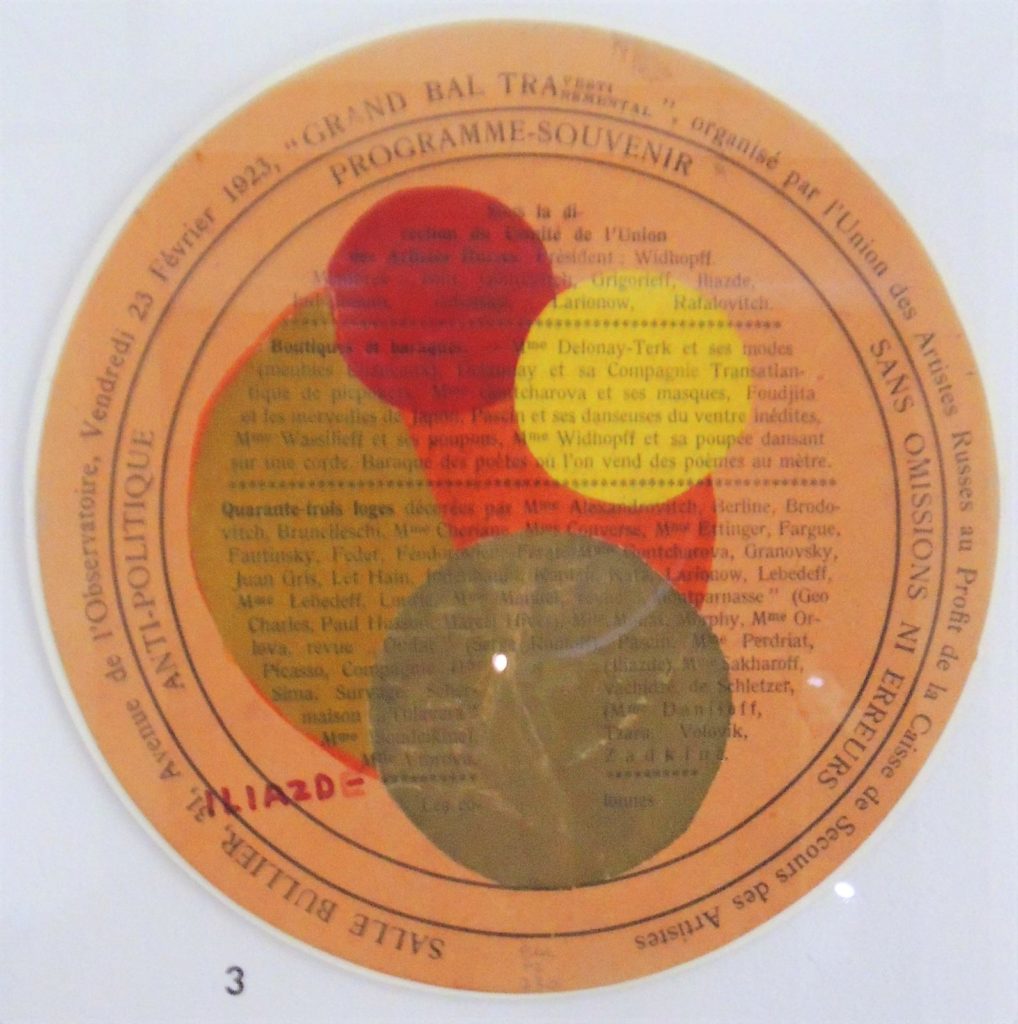

Another section explores the many artists’ balls held regularly in Paris, including invitations, posters, paintings, photographs, and this pochoir program from one evening’s entertainment.

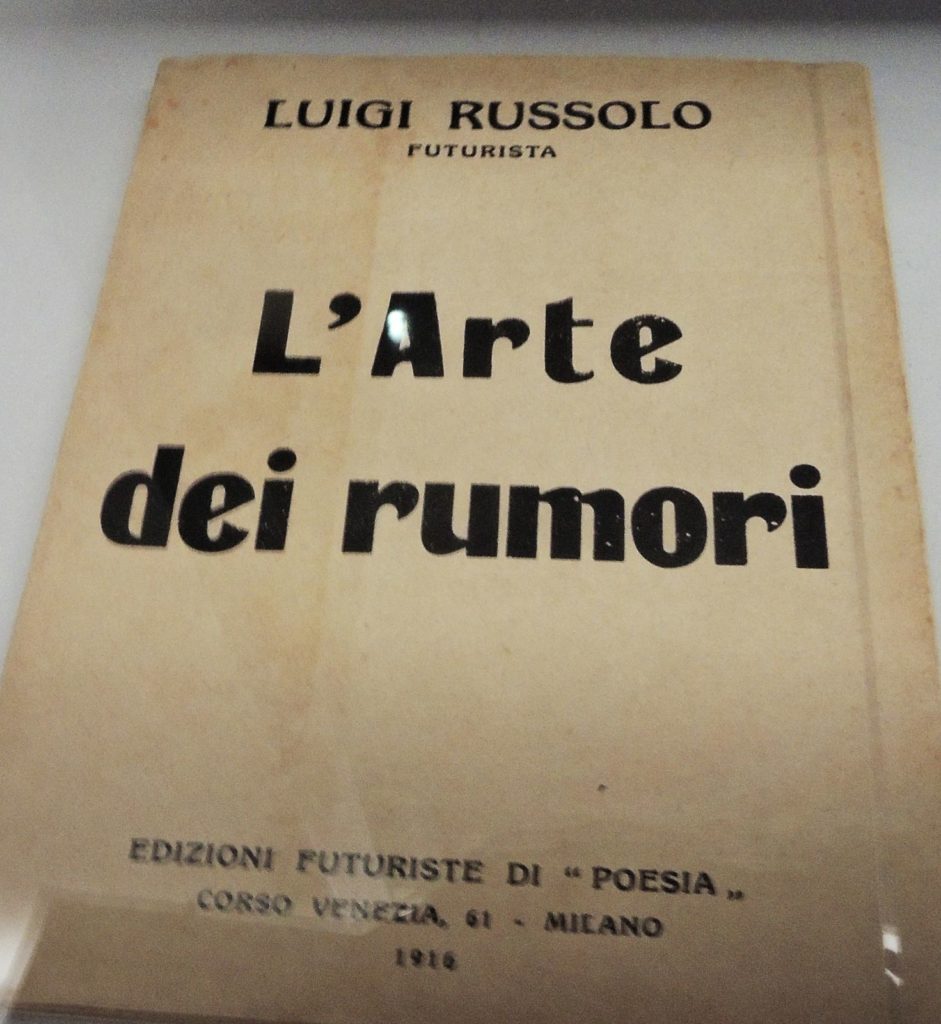

In another corner is Luigi Russolo’s Futurist manifesto The Art of Noises, written in a 1913 letter to Francesco Balilla Pratella and published in 1916. Russolo argues that we have become accustomed to urban industrial sounds and so, they should be incorporated into our music. The museum presents both the visual and the audio documents of the movement. See an English translation here: http://www.artype.de/Sammlung/pdf/russolo_noise.pdf

Luigi Russolo, L’arte dei rumori (Milan: Edizioni futuriste di Poesia, 1916). Marquand Library (SAX): Rare Books ML3877 .R87 1916