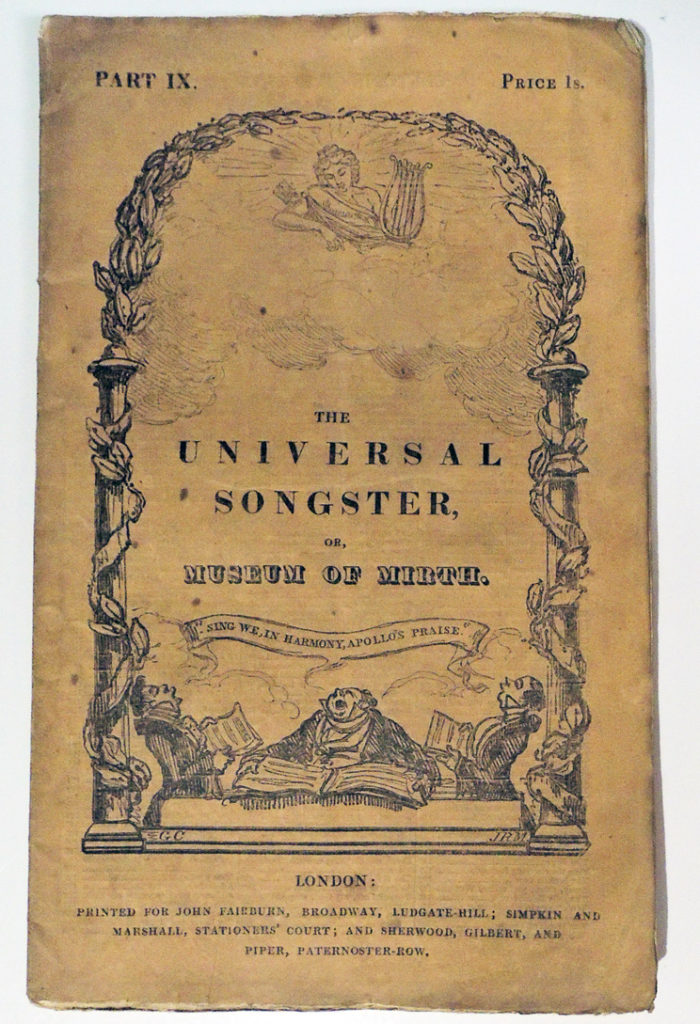

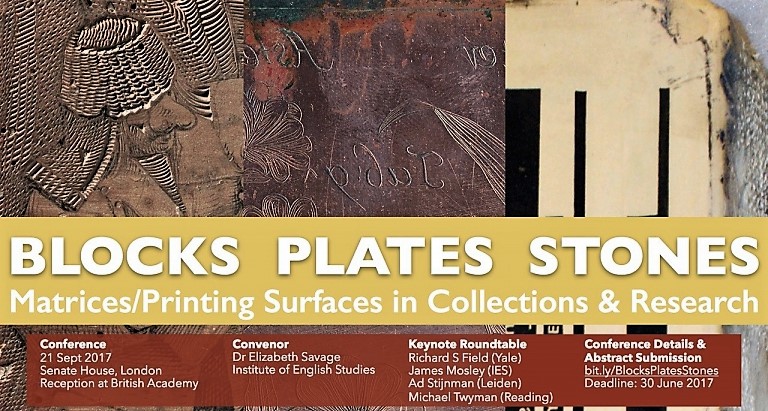

In case you have not seen the announcement, registration is open for the Blocks Plates Stones conference, which has now been moved to the Courtauld Institute, London. https://www.ies.sas.ac.uk/events/event/12642

In case you have not seen the announcement, registration is open for the Blocks Plates Stones conference, which has now been moved to the Courtauld Institute, London. https://www.ies.sas.ac.uk/events/event/12642

Organized by Elizabeth Savage (IES), with help from her committee Giles Bergel (Oxford) and Caroline Duroselle-Melish (Folger), this event is part of a 12-month British Academy Rising Star Engagement Award, ‘The Matrix Reloaded: Establishing Cataloguing and Research Guidelines for Artefacts of Printing Images.’

A draft of the program is now available at: https://symphony-live.s3.amazonaws.com/UhZMp2iSbp7hKGrlphQwBW9X16Bi6li2kFtjXskSC3dcQUA2tbkSRremffd8PtWV/BPS%20Programme-v1.pdf

The keynote roundtable includes Richard S Field (Yale), Maria Goldoni (Galleria Estense), James Mosley (IES), Ad Stijnman (Leiden), Michael Twyman (Reading).

Speakers include Laura Aldovini (Università Cattolica; Cini), Rob Banham (Reading), Jean-Gérald Castex (Louvre), Rosalba Dinoia (independent), Neil Harris (Udine), Konstantina Lemaloglou (Technological Educational Institute of Athens), Huigen Leeflang (Rijksmuseum), Giorgio Marini (Uffizi), Julie Mellby (Princeton), Andreas Sampatakos (Technological Educational Institute of Athens), Linda Stiber Morenus (Library of Congress), Arie Pappot (Rijksmuseum), Elizabeth Savage (IES), Jane Rodgers Siegel (Columbia), Femke Speelberg (Met), and Amy Worthen (Des Moines Art Centre).

Object sessions and posters by: Constança Arouca (Orient Museum), Teun Baar (Apple), Cathleen A. Baker (Michigan), Rob Banham (Reading), Maarten Bassens (Royal Library of Belgium; KU Leuven), Giles Bergel (Oxford), Annemarie Bilclough (V&A), Chris Daunt (Society of Wood Engravers), Gigliola Gentile (Sapienza), Jasleen Kandhari (Leeds), Nicholas Knowles (Independent), Peter Lawrence (Society of Wood Engravers), Marc Lindeijer SJ (Société des Bollandistes), Anna Manicka (National Museum, Warsaw), Peter McCallion (West of England), Melissa Olen (West of England), Maria V. Ortiz-Segovia (Océ Print Logic Technologies), Carinna Parraman (West of England), Marc Proesmans (KU Leuven), Rose Roberto (Reading; National Museums Scotland), Fulvio Simoni (Bologna), Francesca Tancini (Bologna), Joris Van Grieken (Royal Library of Belgium), Bruno Vandermeulen (KU Leuven), Genevieve Verdigel (Warburg), Lieve Watteeuw (Illuminare), Christina Weyl (independent), and Hazel Wilkinson (Birmingham).

Hope to see everyone there.