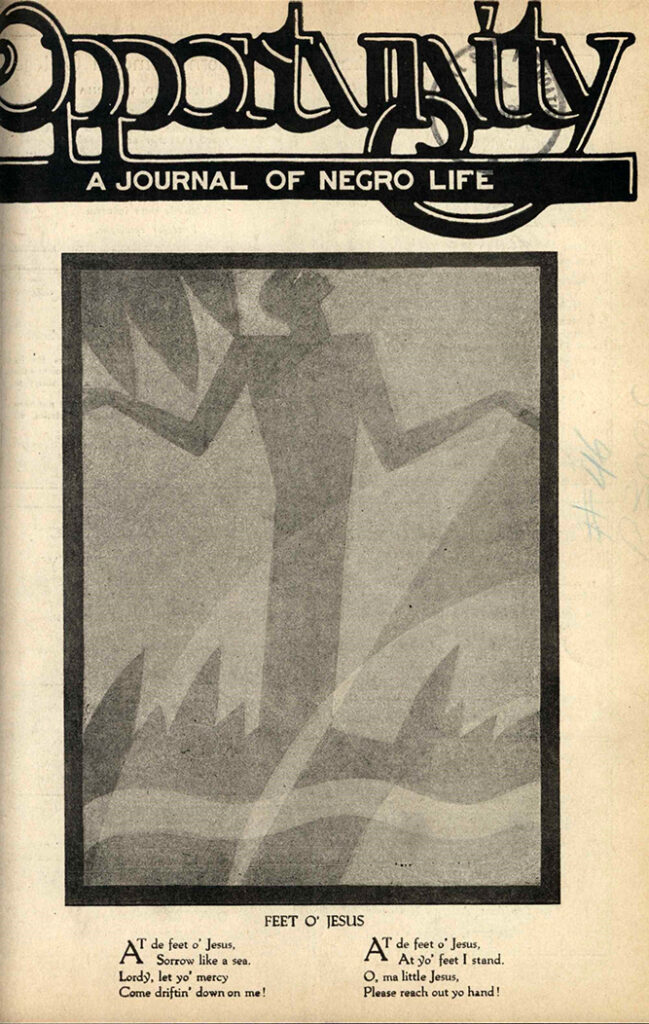

The artists of Opportunity, the monthly publication of the National Urban League edited by Charles S. Johnson, were always identified in the table of contents but almost never given further biographical details in magazine’s “Who’s Who” or other text. Here are some of the leading graphic artists from the late 1920s, before photography took over. Perhaps not surprisingly, some were Black and some White. Covers are printed on a tan stock that photographed grey here.

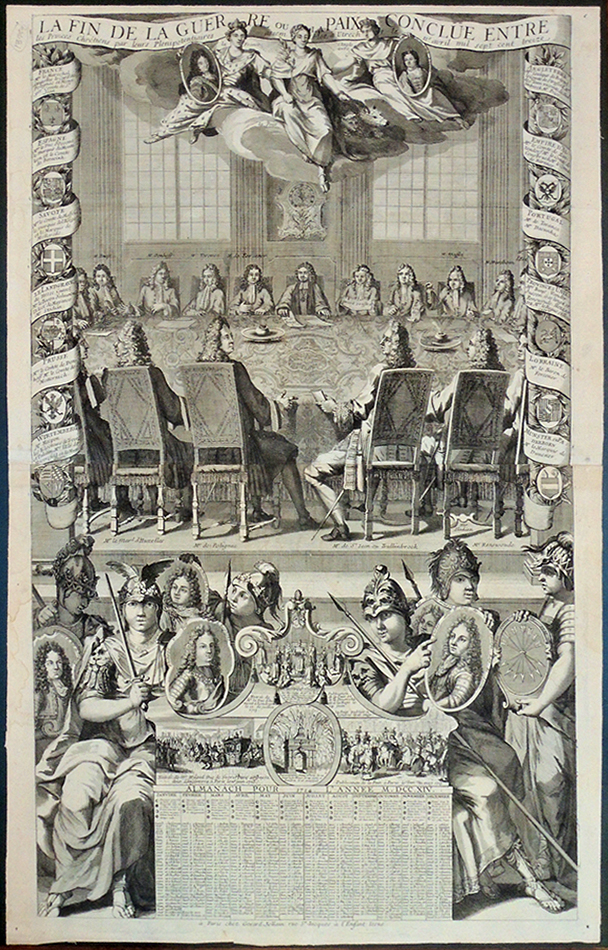

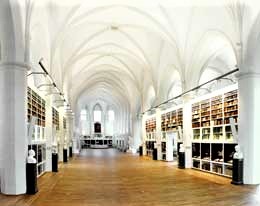

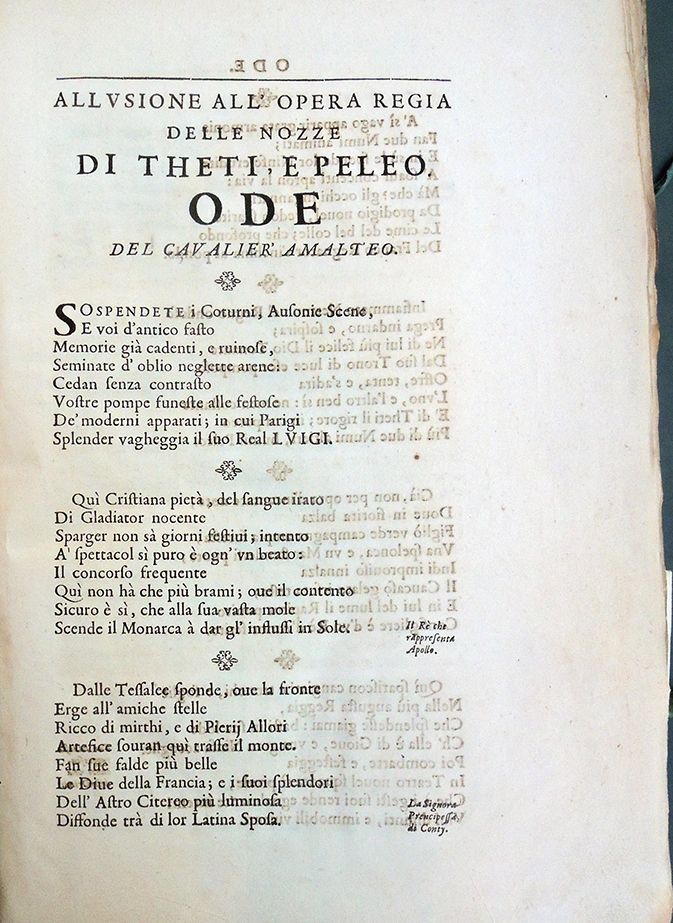

Winold Reiss, “Langston Hughes,” Opportunity 5, no. 3 (March 1927).

Winold Reiss, “Langston Hughes,” Opportunity 5, no. 3 (March 1927).

Winold Reiss (1886–1953) No information is provided by Opportunity, even in “Who’s Who.” A White German American artist, Winold Reiss arrived in New York City in 1913, where he soon began creating sensitive representations of African Americans and Native Americans. “Reiss’s depictions avoided the racist stereotypes common at the time.” Along with his student Aaron Douglas, Reiss illustrated The New Negro: An Interpretation, a collection of Harlem literary works by Alain Leroy Locke, the first African American Rhodes scholar.—Details from National Portrait Gallery.

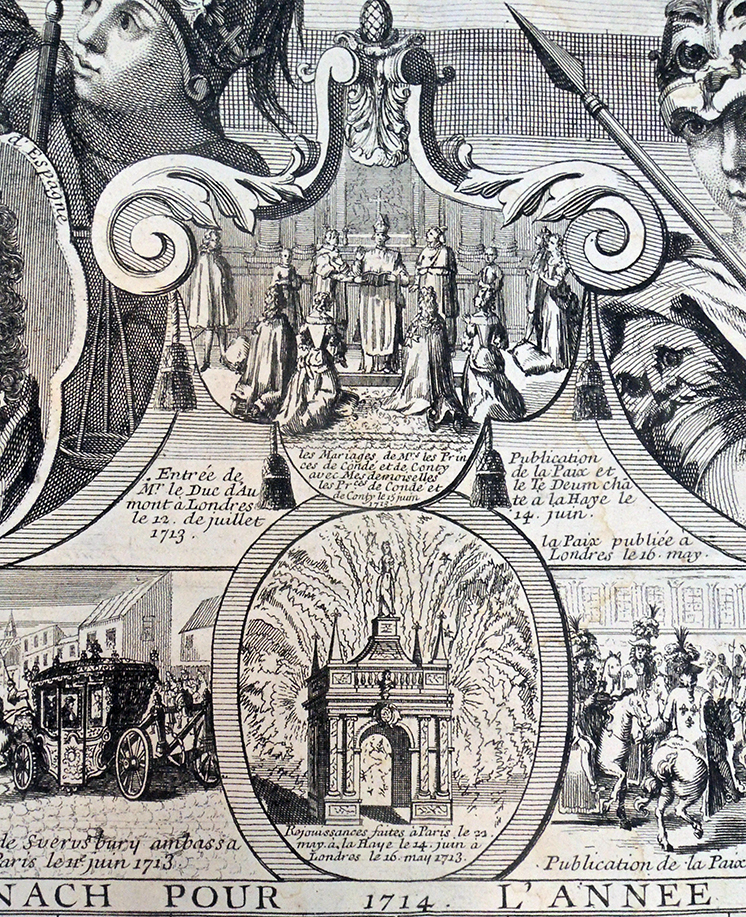

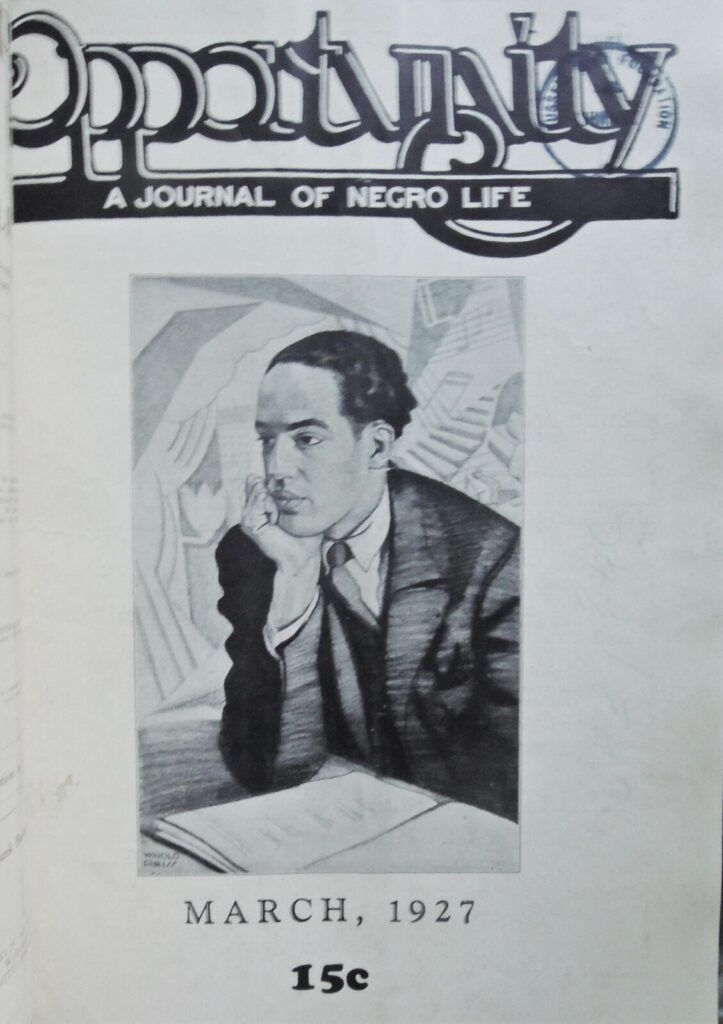

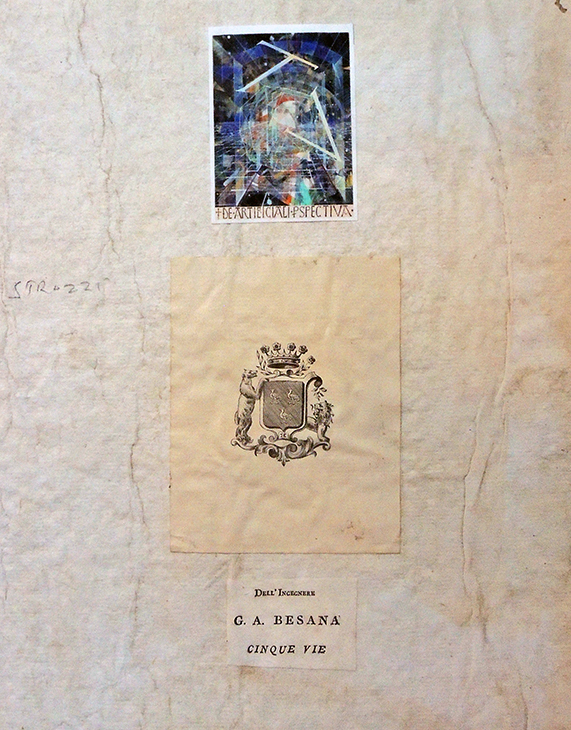

Aaron Douglas, [Untitled], Opportunity 5, no. 5 (May 1927).

Aaron Douglas, [Untitled], Opportunity 5, no. 5 (May 1927).

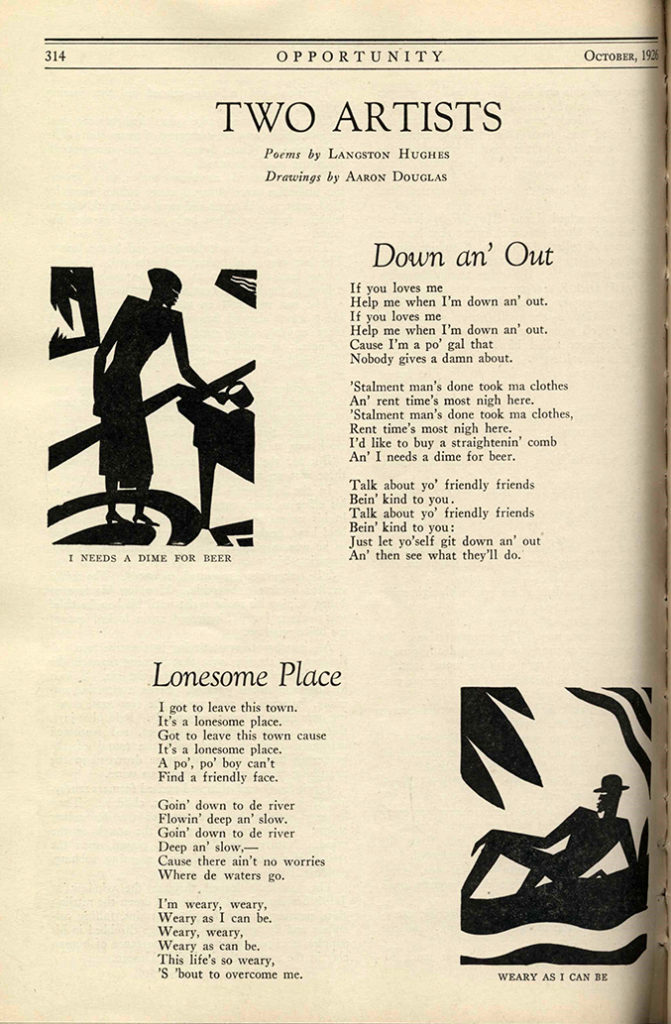

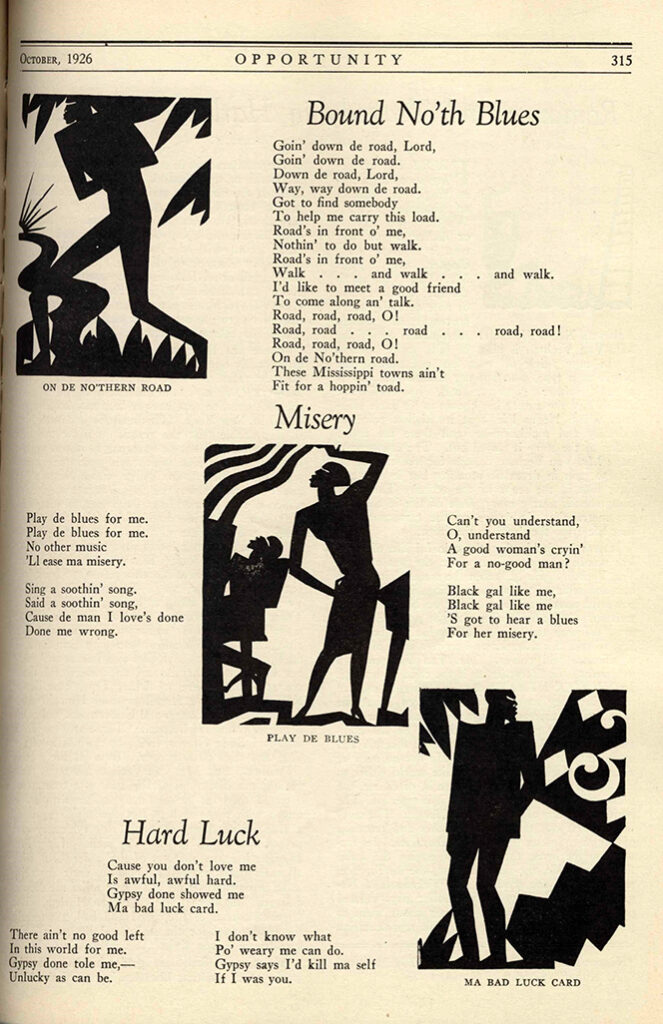

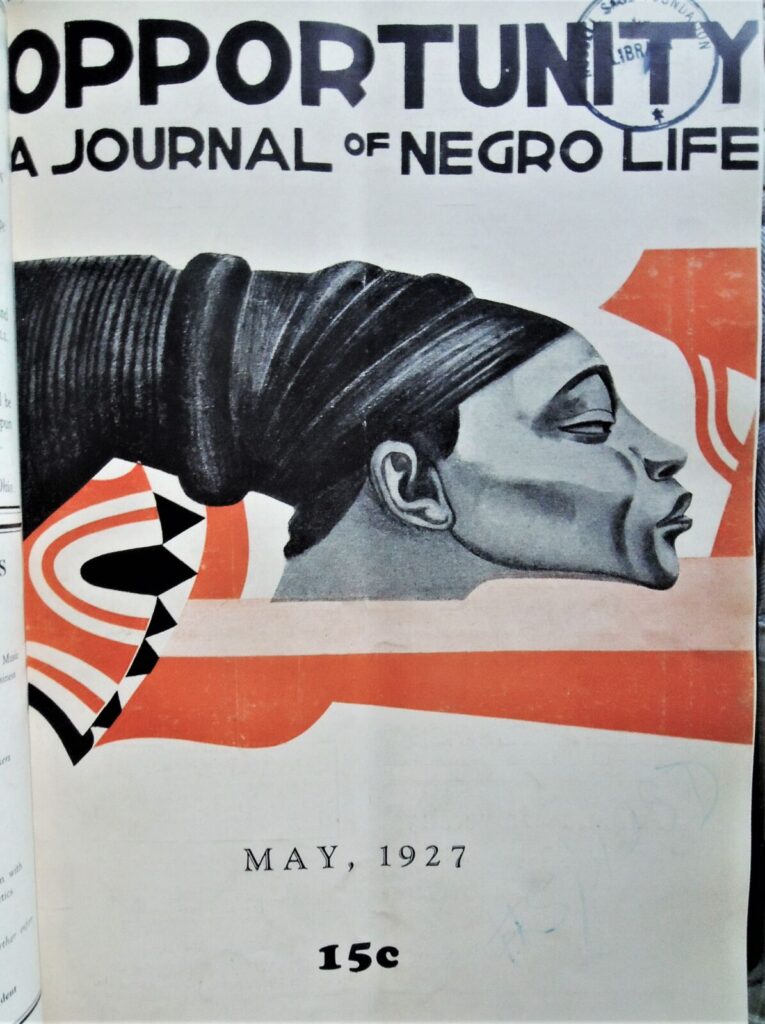

Aaron Douglas (1899-1979). “Douglas arrived in Harlem shortly after the publication of what was immediately recognized as a landmark publication: the March 1925 issue of Survey Graphic titled, “Harlem: Mecca for the New Negro” [later published in The New Negro]. … [In New York, he studied] with German émigré artist Fritz Winold Reiss… and Du Bois, who gave him a job in the mail room of The Crisis. In 1927 … Douglas to join the staff of The Crisis as their art critic… and …illustrated God’s Trombones: Seven Negro Sermons in Verse by James Weldon Johnson. Douglas became chairman of the art department at Fisk University while also remaining active in Harlem.—”Aaron Douglas: African American Modernist,” ed. Susan Earle (2007).

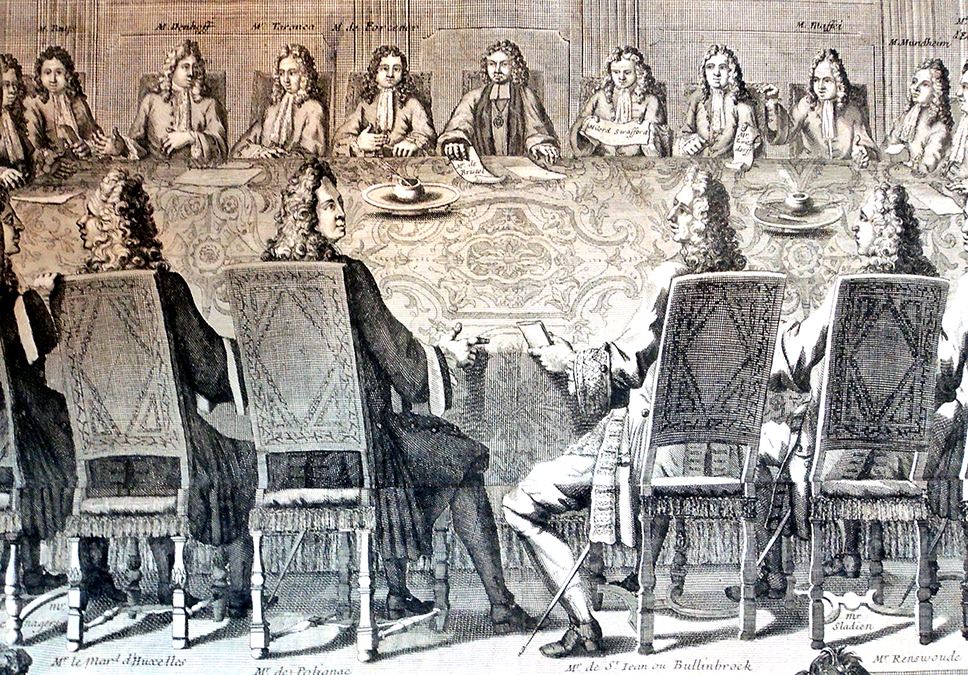

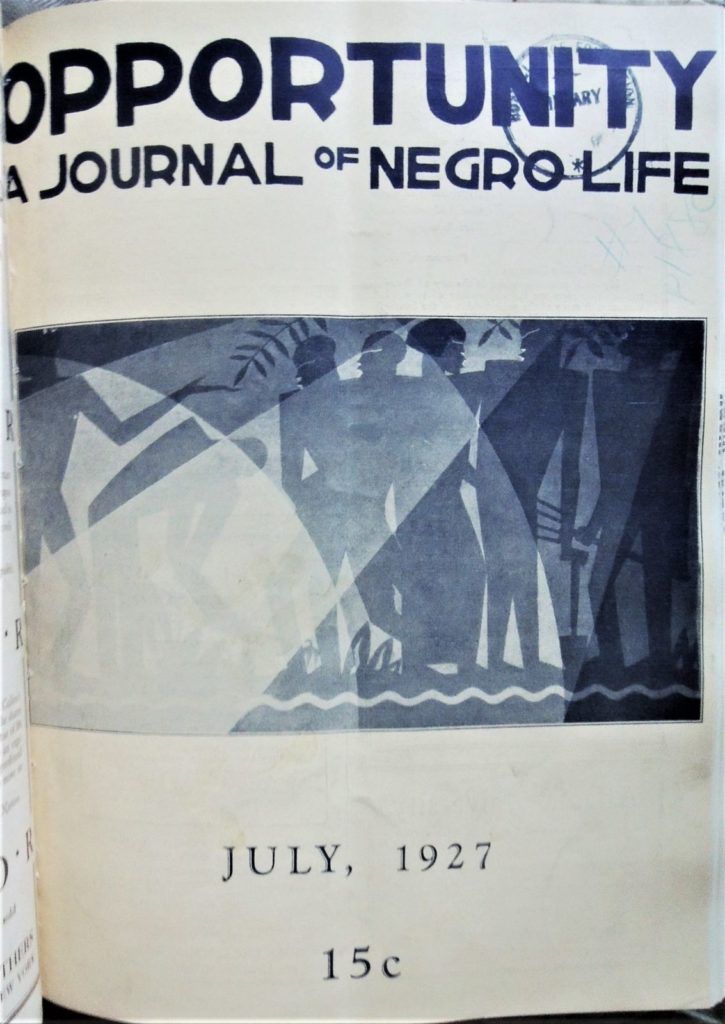

Aaron Douglas, [Untitled], Opportunity 5, no. 7 (July 1927).

Aaron Douglas, [Untitled], Opportunity 5, no. 7 (July 1927).

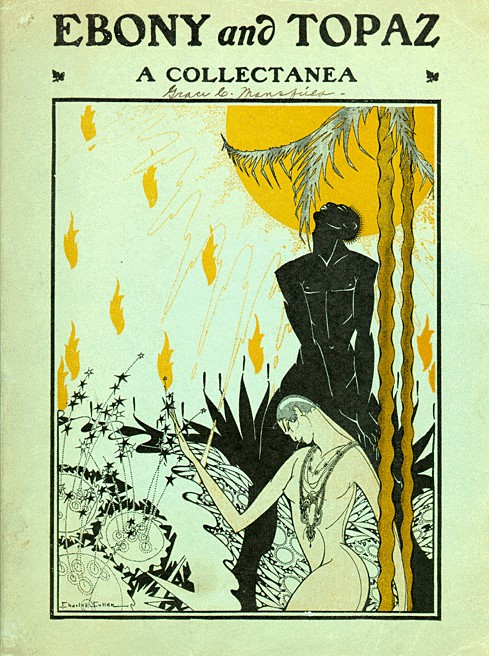

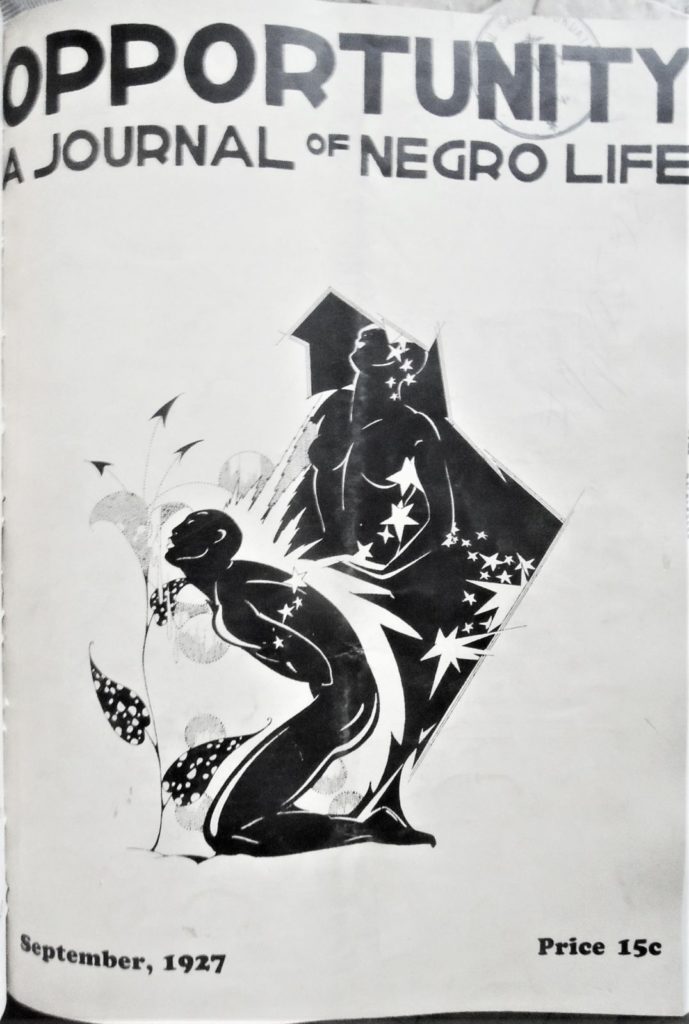

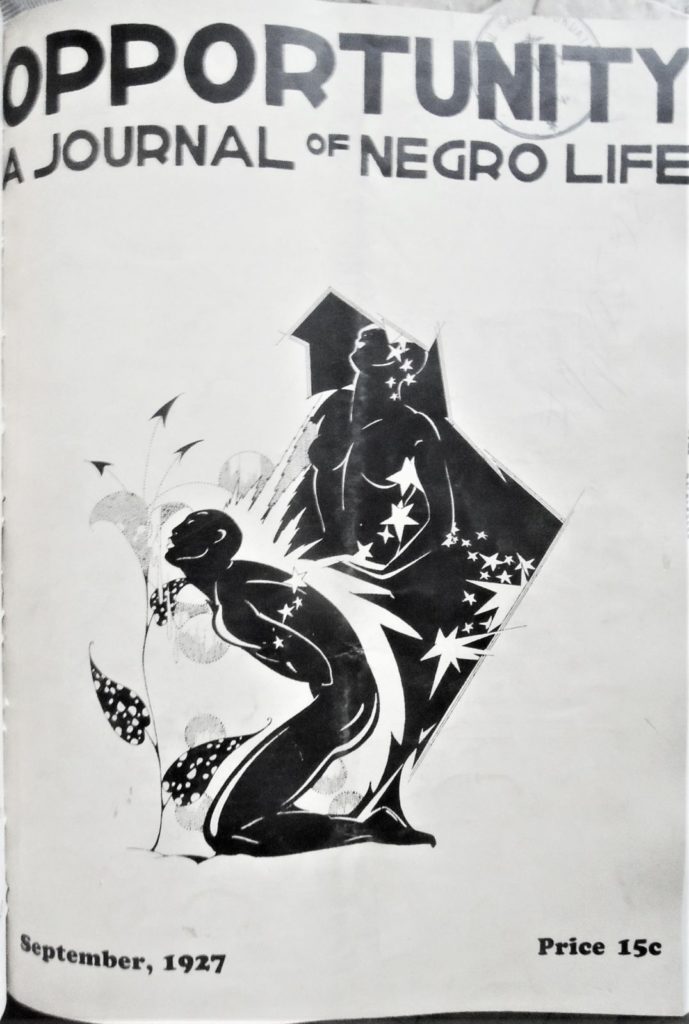

Charles Cullen, “A Copper Sun,” Opportunity 5, no. 9 (September 1927).

Charles Cullen, “A Copper Sun,” Opportunity 5, no. 9 (September 1927).

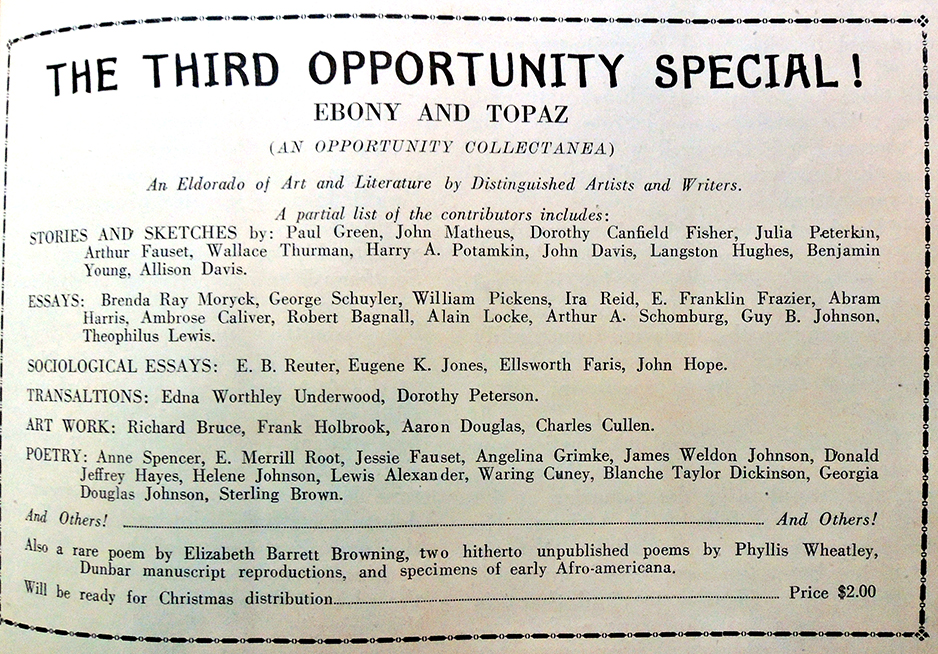

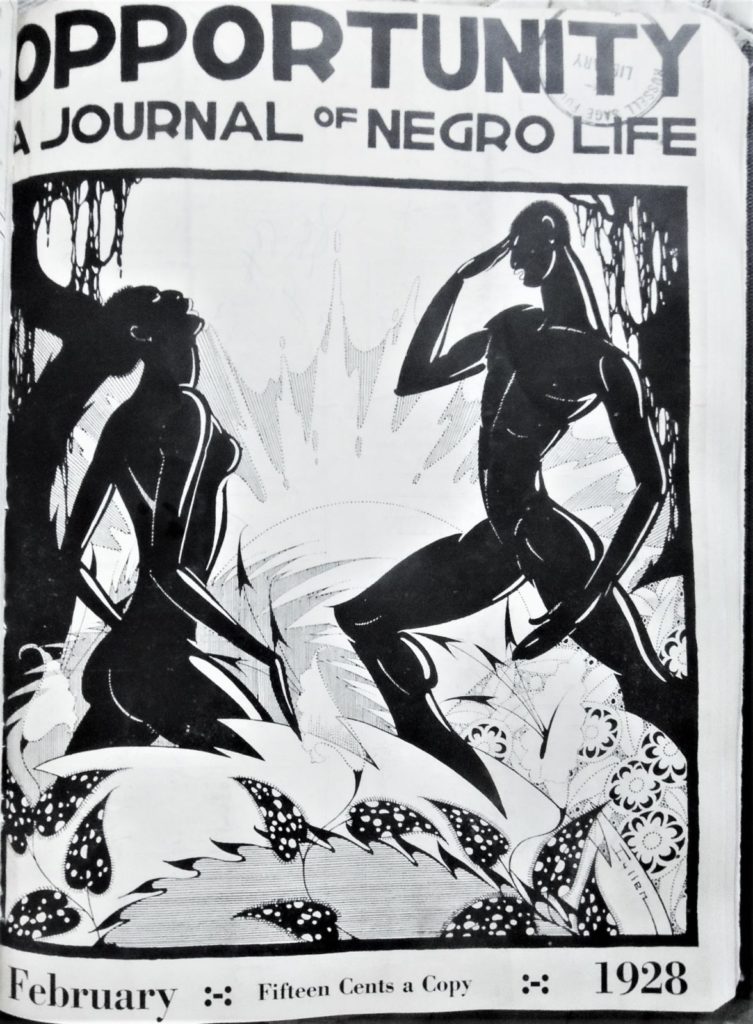

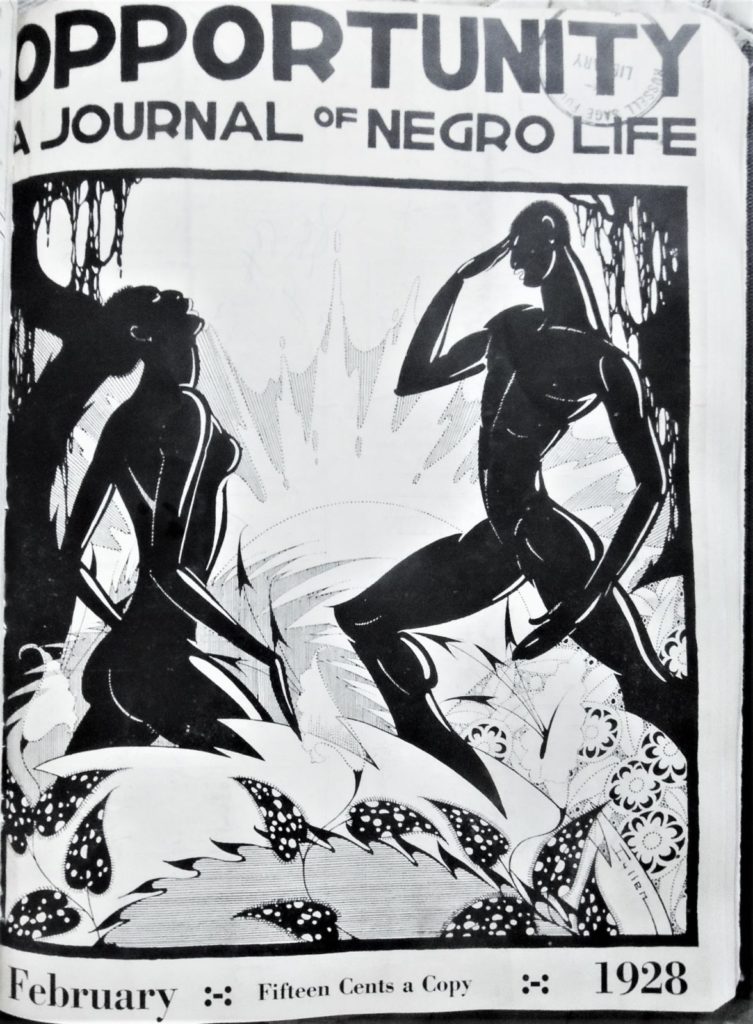

Charles Cullen (born 1887). A White Irish American artist, influenced by Aubrey Beardsley, Cullen illustrated many of Countee Cullen’s early poetry books. These designs are often repeated in the magazines or advertisements of the period. “Countee Cullen tells an interesting tale about how the father of Charles Cullen is always interested in anyone whose name is Cullen…it was in this way that he came to buy Color, Countee Cullen’s first book, the which he sent to his son Charles…it later developed that Charles was an artist… hence these very beautiful drawings which he did for Countee Cullen’s book…and truly they are lovely to behold!” Opportunity September 1927, p. 277.

Charles Cullen, [Untitled], Opportunity 6, no. 2 (February 1928).

Charles Cullen, [Untitled], Opportunity 6, no. 2 (February 1928).

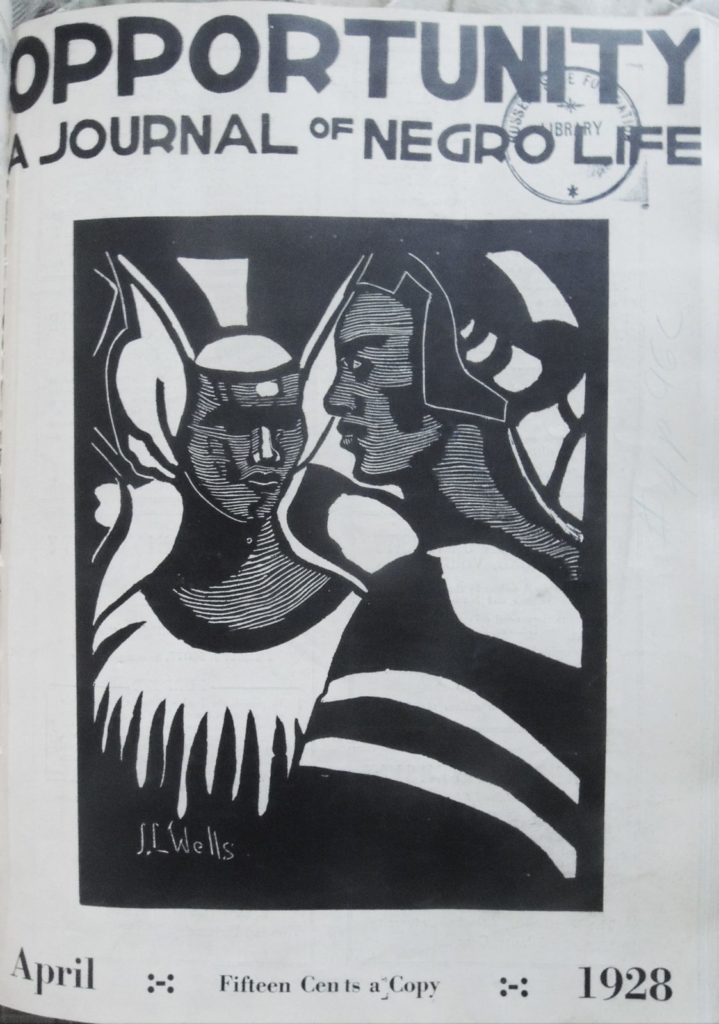

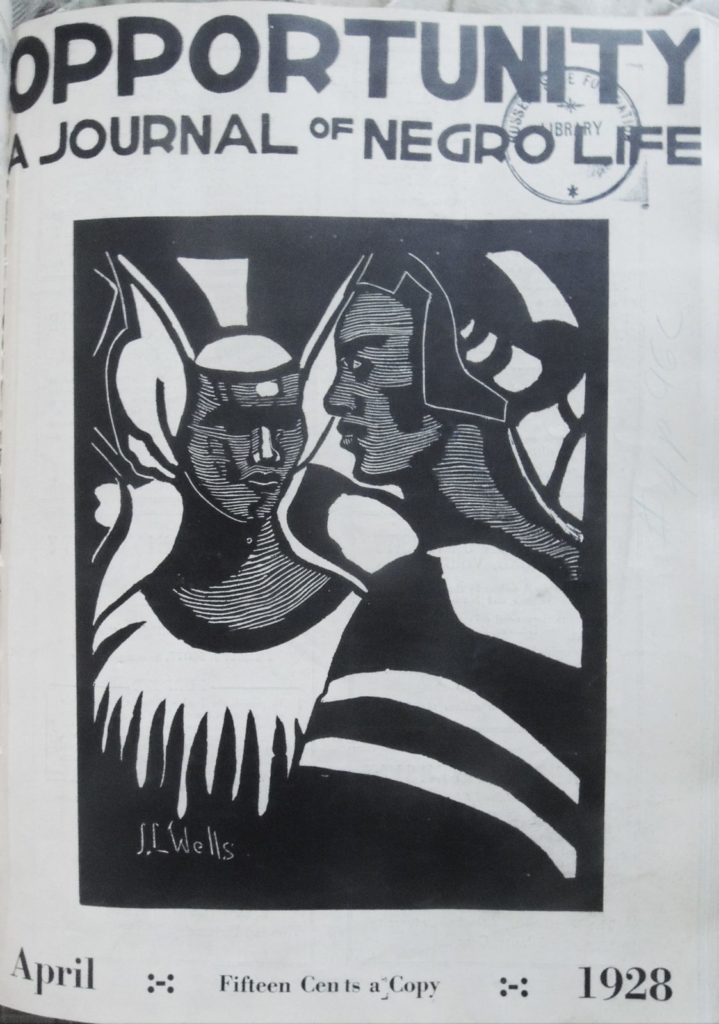

James L. Wells, [Untitled], Opportunity 6, no. 4 (April 1928).

James L. Wells, [Untitled], Opportunity 6, no. 4 (April 1928).

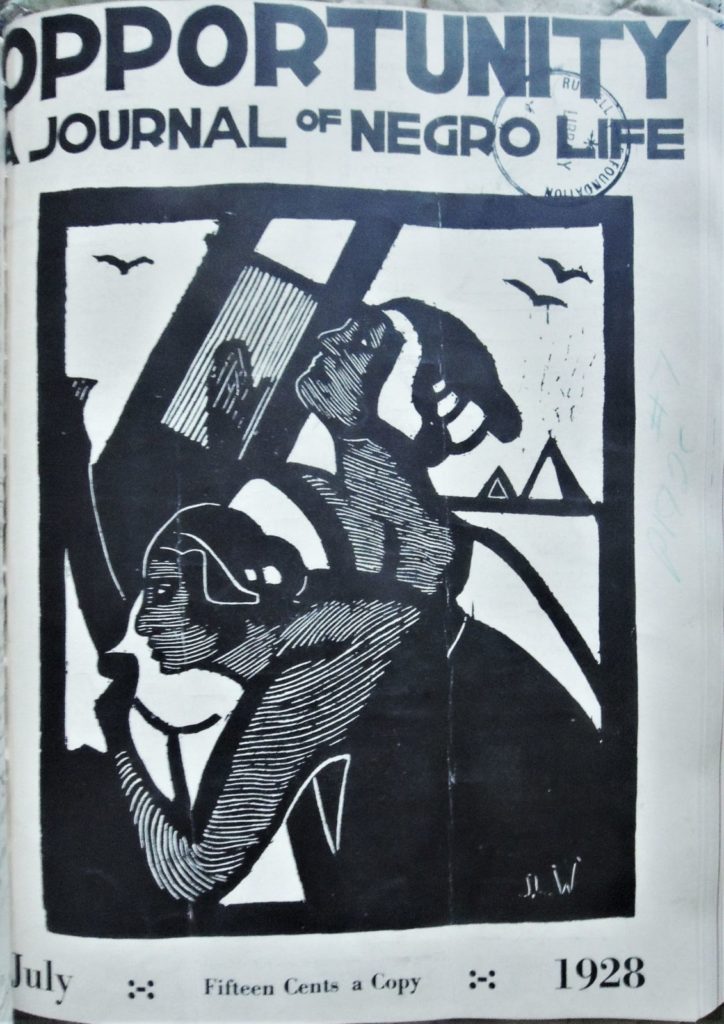

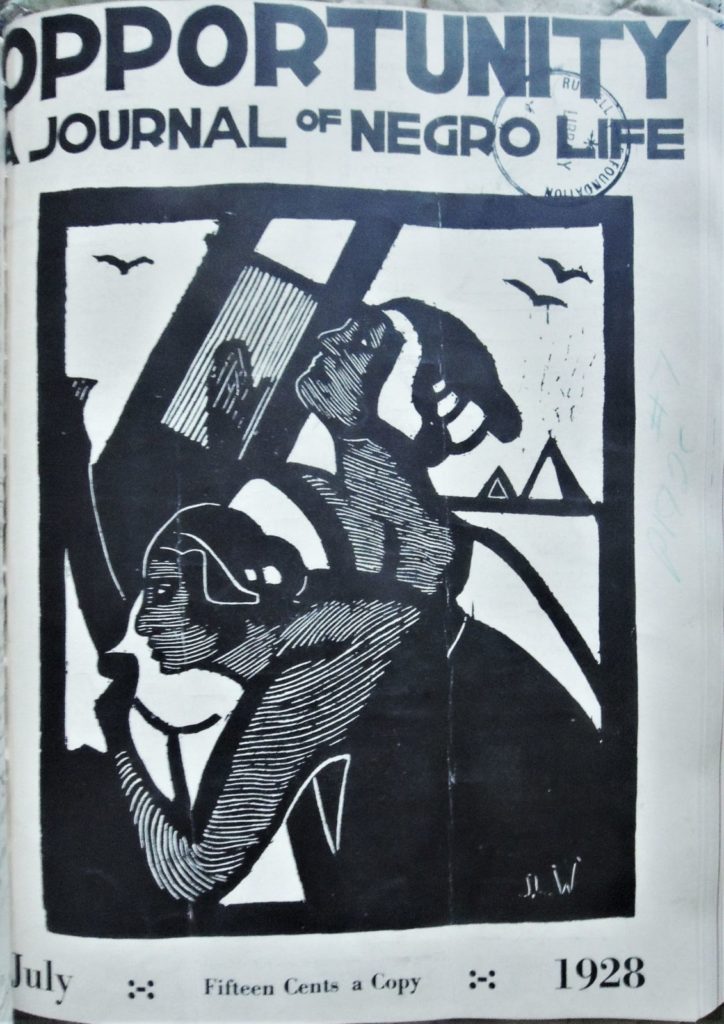

James Lesesne Wells (1902-1993). Described in Opportunity as a “Young Negro artist living in Buffalo.” Wells studied in New York City at Teachers College and the National Academy of Design, where the owner of the New Art Circle Gallery, J.B. Neumann, saw his work and included him in the “International Modernists” exhibition in 1929. Wells became a crafts instructor at Howard University, teaching block printing, ceramics, clay modeling, and sculpture. He also developed professional and personal relationships with Alain Locke, historian Carter G. Woodson, and later, Stanley Hayter, while further developing his printmaking skills at Hayter’s Atelier 17.

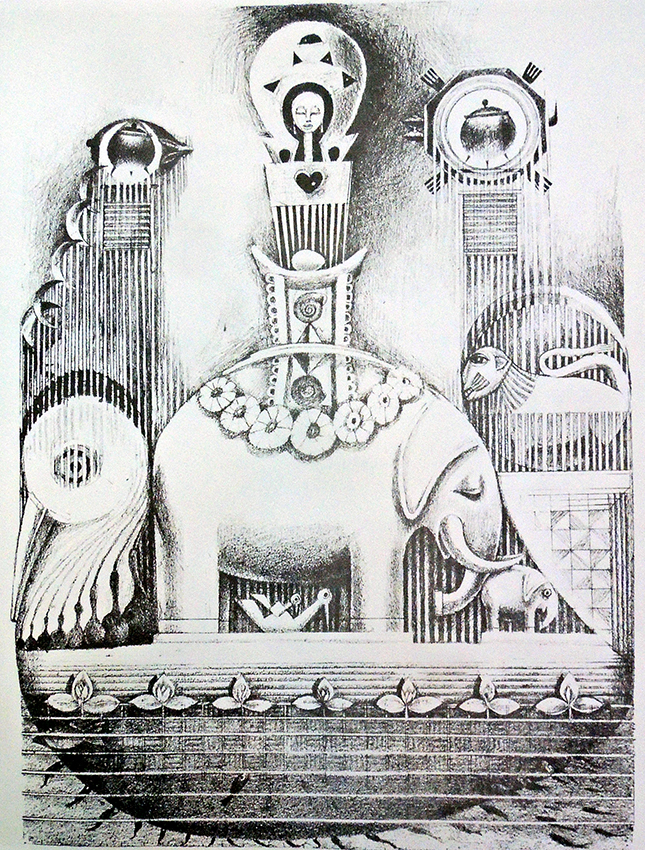

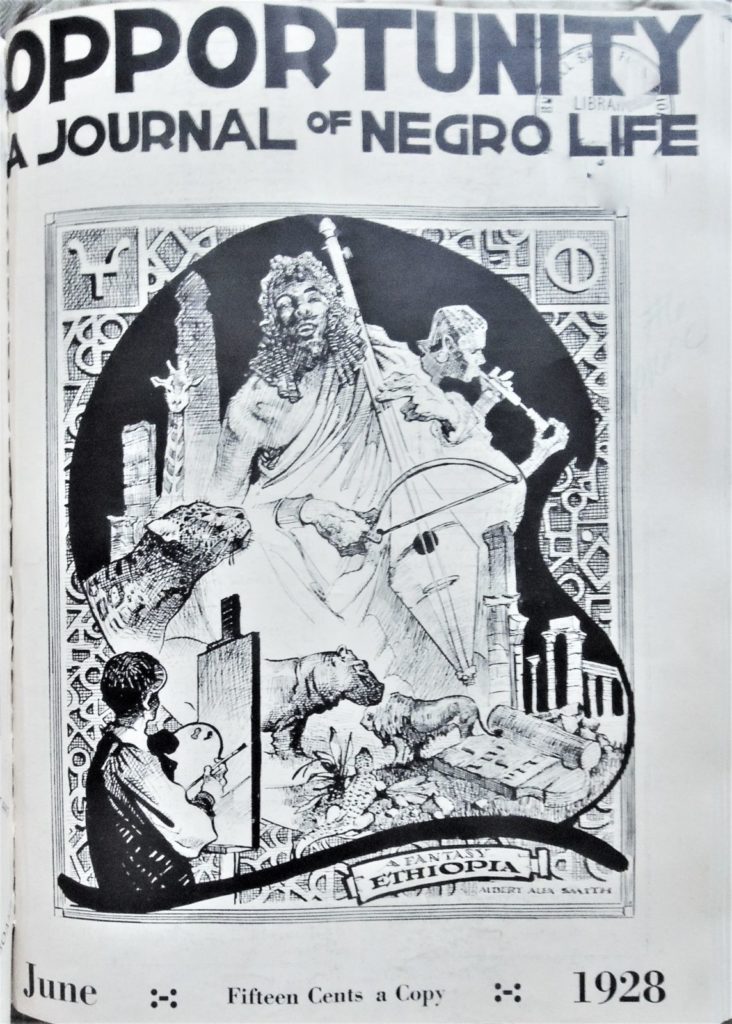

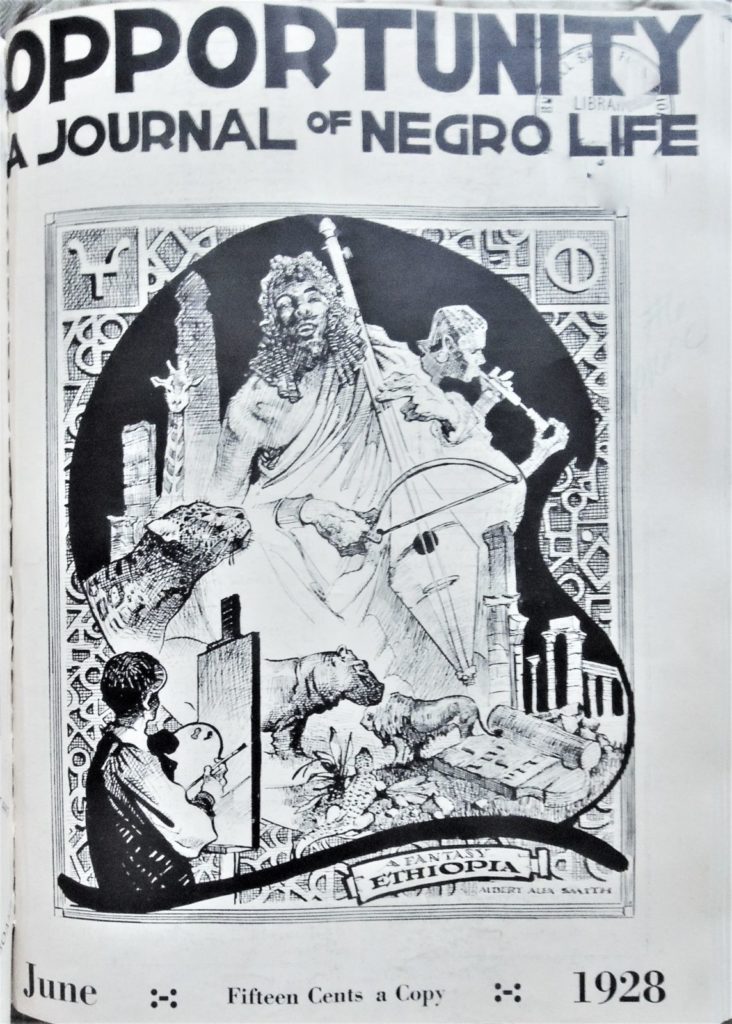

Albert A. Smith, “Ethiopia–A Fantasy,” Opportunity 6, no. 6 (June 1928).

Albert A. Smith, “Ethiopia–A Fantasy,” Opportunity 6, no. 6 (June 1928).

Albert Alexander Smith (1896-1940), Listed in Opportunity as “A young Negro artist now on a visit in this country from Paris where he has resided for the past seven years.” Smith was the first African American to win a scholarship to the High School of Ethical Culture and the first African American to study at the National Academy of Design. In 1920 his work was published in Crisis, shortly before he left the United States to live permanently in Europe. Often sending work back to the States, he continued to publish in Opportunity and elsewhere but died suddenly in France only forty-four years old.

James Lesesne Wells, [Untitled], Opportunity 6, no. 7 (July 1928).

James Lesesne Wells, [Untitled], Opportunity 6, no. 7 (July 1928).

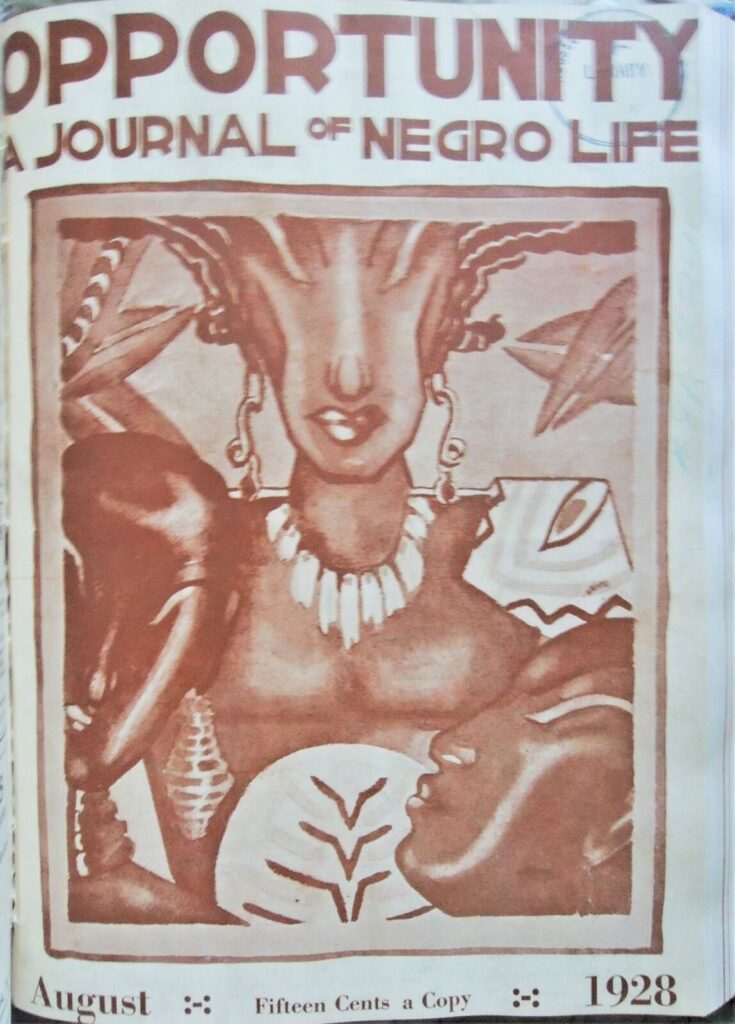

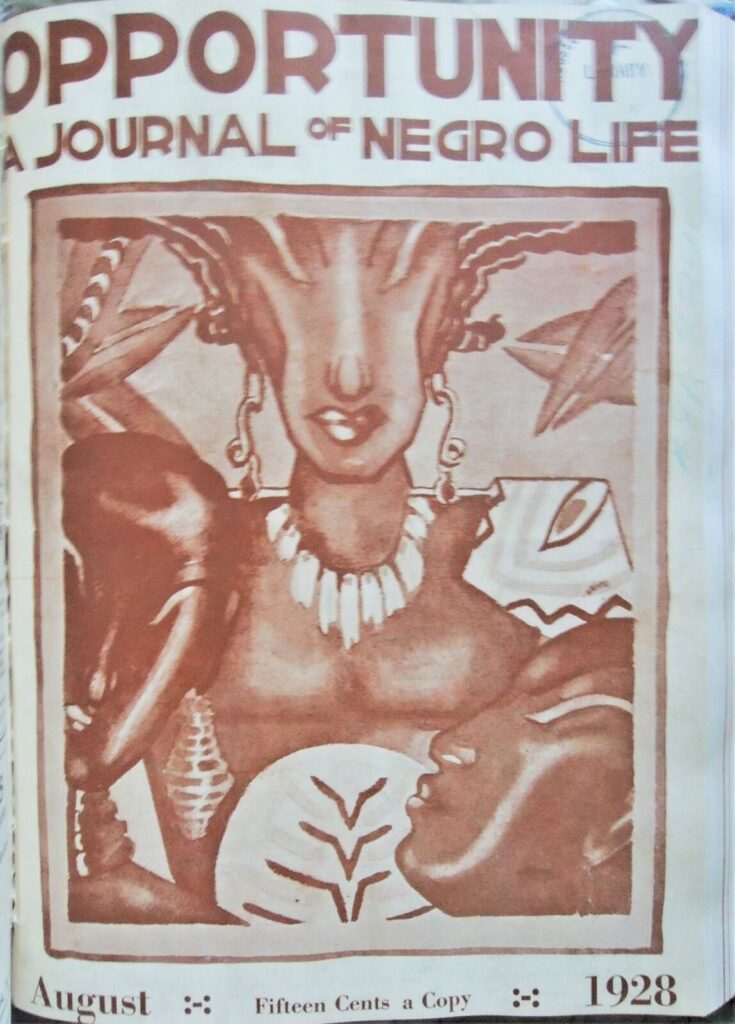

Lois Jones, [Untitled], Opportunity 6, no. 8 (August 1928).

Lois Jones, [Untitled], Opportunity 6, no. 8 (August 1928).

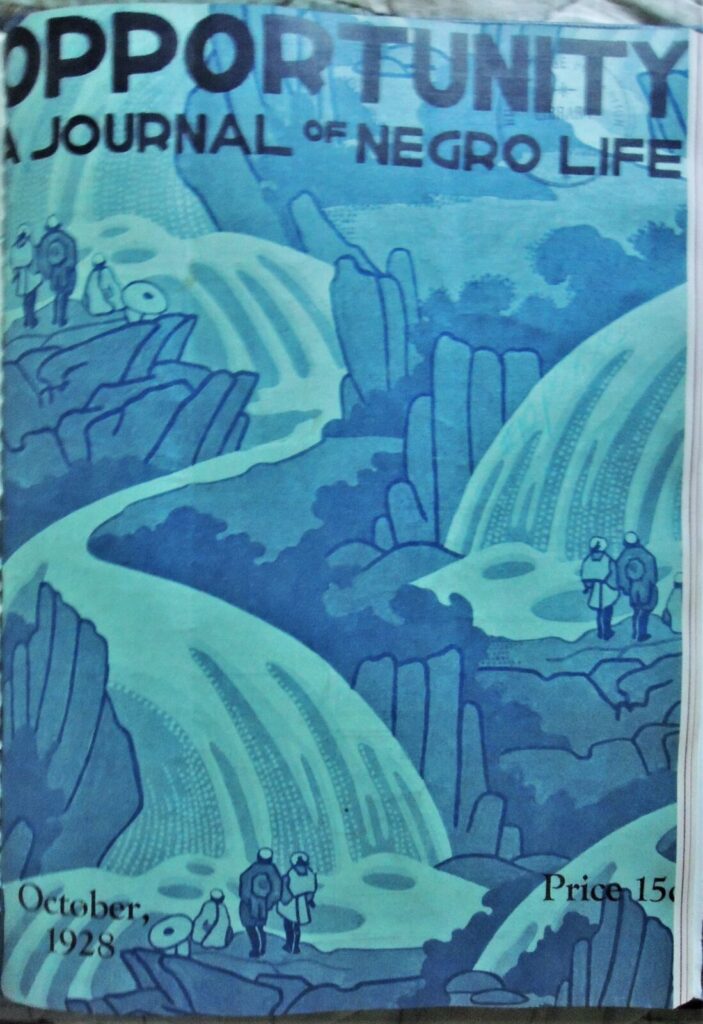

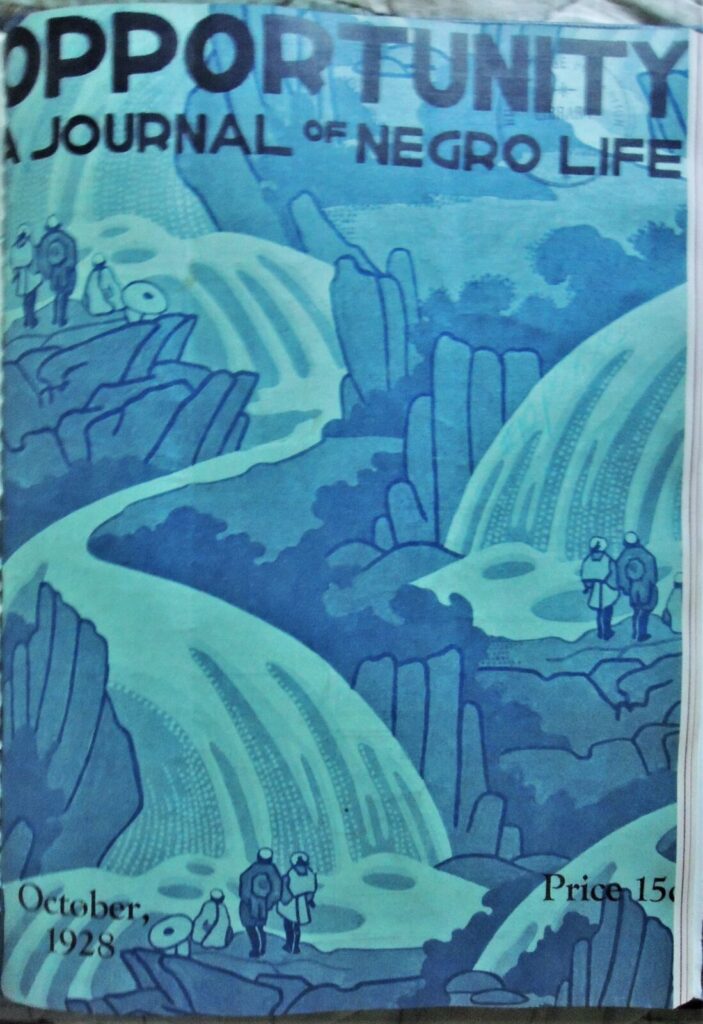

Lois Jones (1905-1998). Opportunity described her as “A promising young artist living in Boston.” In 1928 Jones formed and chaired the art department at the Palmer Memorial Institute in North Carolina, and two years later was recruited to teach at Howard University in Washington, D.C., [where she] taught design and watercolor painting for the next forty-seven years…. In 1937 Jones received a year-long fellowship that took her to Paris to live and work. This was a defining moment for the young black artist who experienced—for the first time in her life—the complete freedom to live as she wished without the indignities of segregation that she felt in the United States.”—Phillips Collection.

“In 1941, Jones entered her painting “Indian Shops Gay Head, Massachusetts” into the Corcoran Gallery’s annual competition. At the time, the Corcoran Gallery prohibited African-American artists from entering their artworks themselves. Jones had [a White artist] Céline Marie Tabary enter her painting to circumvent the rule. Jones ended up winning the Robert Woods Bliss Award for this work of art, yet she could not pick up the award herself. Tabary had to mail the award to Jones. …In 1994, the Corcoran Gallery of Art gave a public apology to Jones at the opening of the exhibition The World of Lois Mailou Jones, 50 years after Jones hid her identity.” –Karla Araujo, “Against All Odds,” Martha’s Vineyard Magazine.

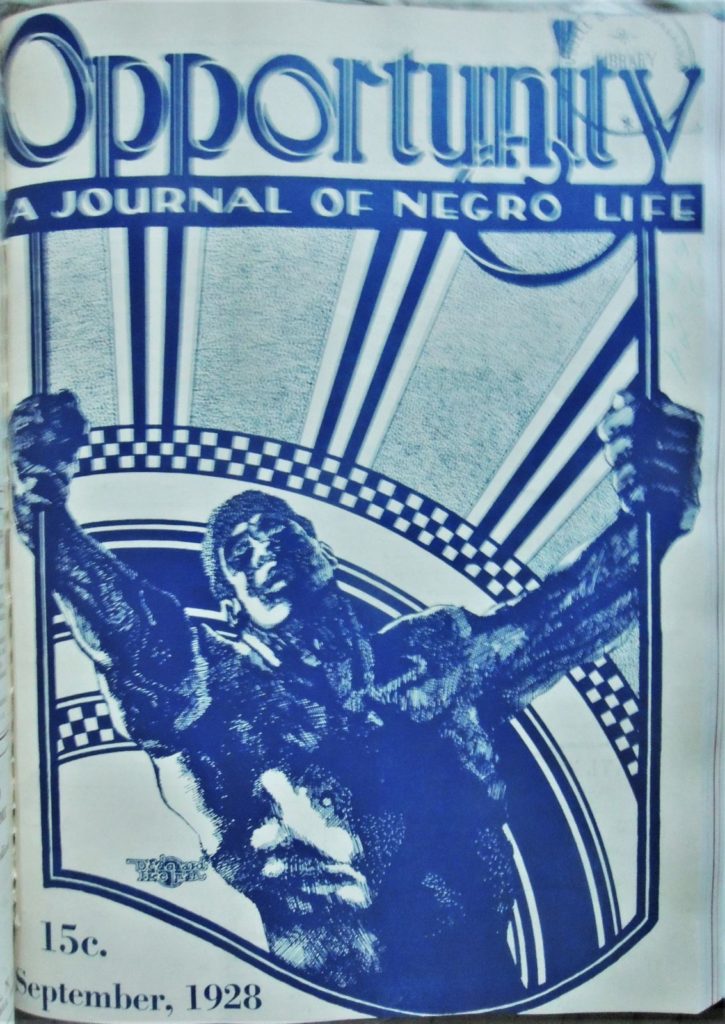

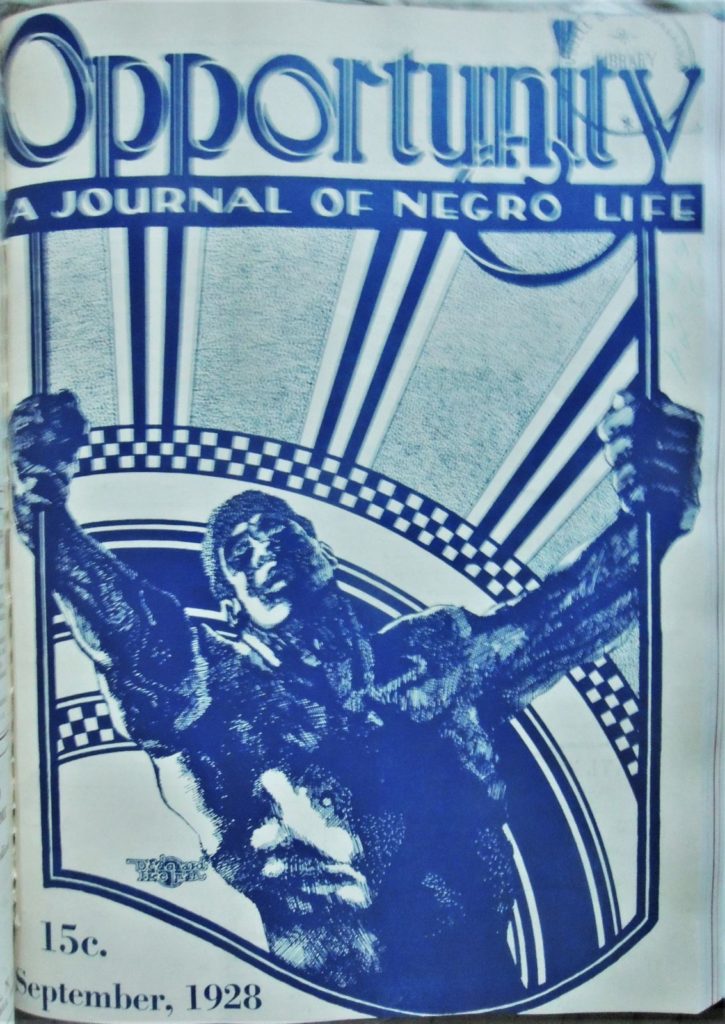

D. Edouard Freeman, [Untitled], Opportunity 6, no. 9 (September 1928).

D. Edouard Freeman, [Untitled], Opportunity 6, no. 9 (September 1928).

The artist is listed in Opportunity as an “Instructor in drawing at Tuskegee.” Nothing else is known.

Lois Jones, [Untitled], Opportunity 6, no. 10 (October 1928).

Lois Jones, [Untitled], Opportunity 6, no. 10 (October 1928).

Also included: Cornelius Marion Battey (1873-1927). Many of the early cover designs for Opportunity were created by photographer C.M. Battey, who, in his last years of life, turned to pen and brush. A short obituary is printed in Opportunity, May 1927, p. 126. Battey moved from Cleveland to New York City “where for six years he was superintendent of the Bradley Photographic Studio on Fifth Avenue. He went to work at the city’s most famous photographic company, Underwood and Underwood, where he was put in charge of the retouching department. Battey finally got the opportunity to work on his own. With a partner he opened the Battey and Warren Studio in New York. …Battey was one of the best pictorialists in New York City.

His work led him into a valuable friendship with black author and educator W. E. B. DuBois, one of the founders of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). DuBois was also editor of the NAACP’s official magazine, The Crisis. Soon Battey’s portraits of well-known black leaders were appearing regularly on the covers of The Crisis. In 1916, Battey was invited to take over the photography department of the Tuskegee Institute in Tuskegee, Alabama [where] Battey not only taught photography but also chronicled in pictures the life of the campus.” – Black Artists in Photography (1840-1940) by George Sullivan.

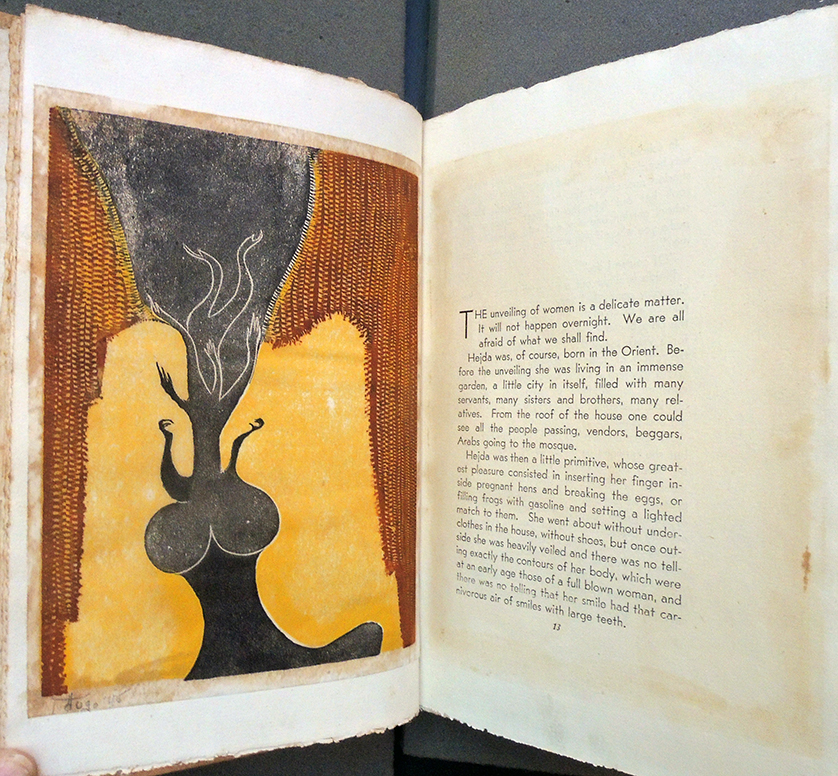

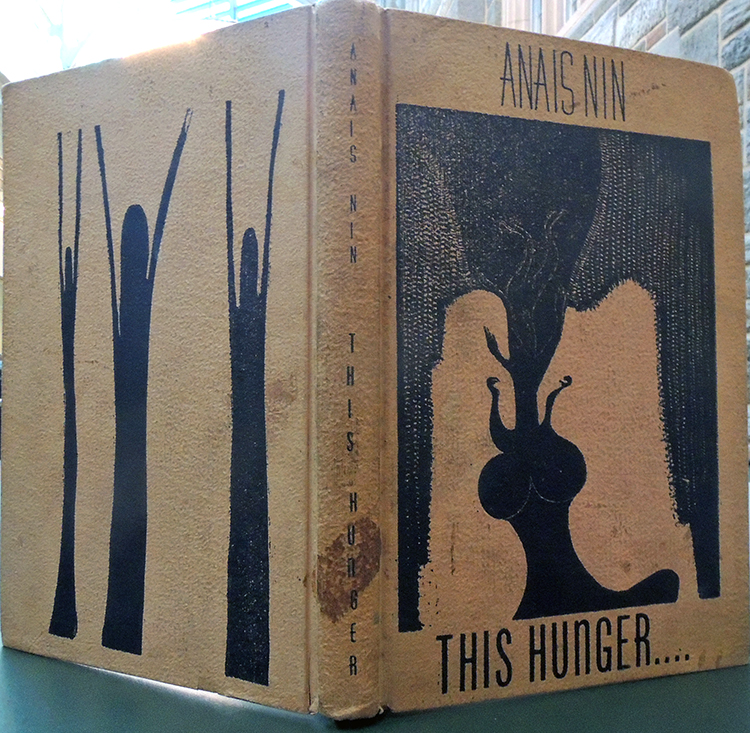

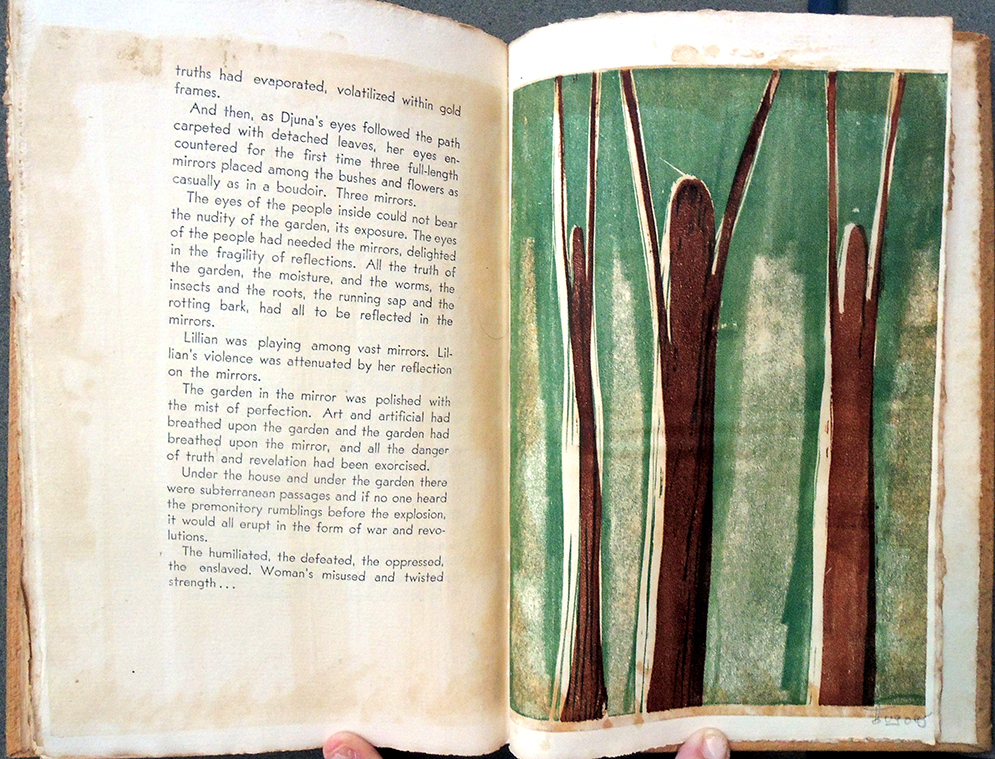

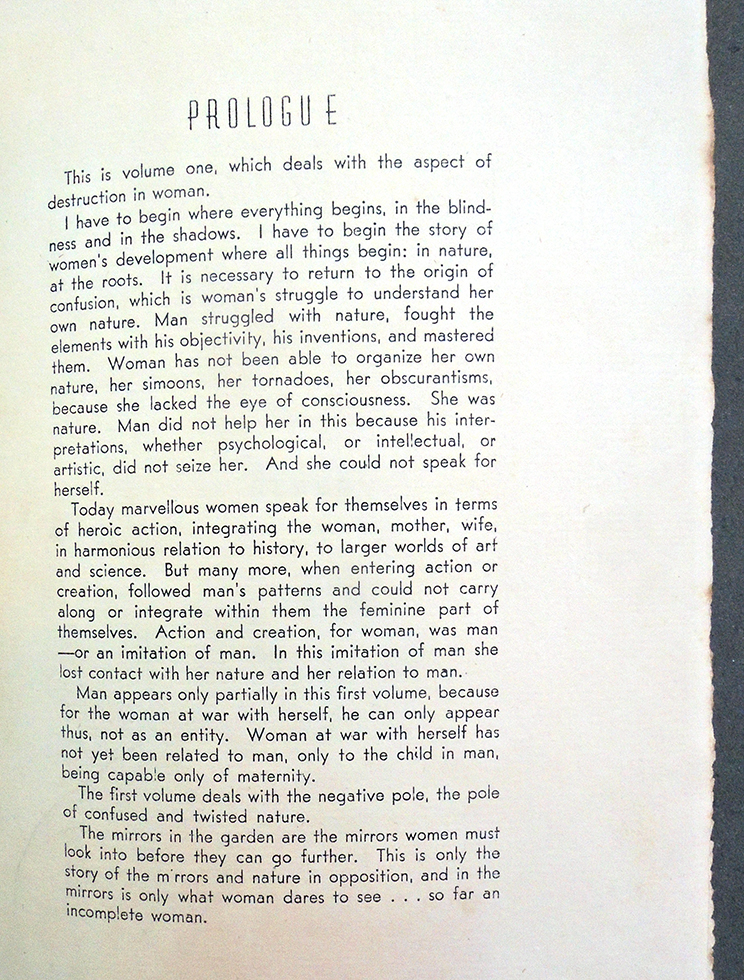

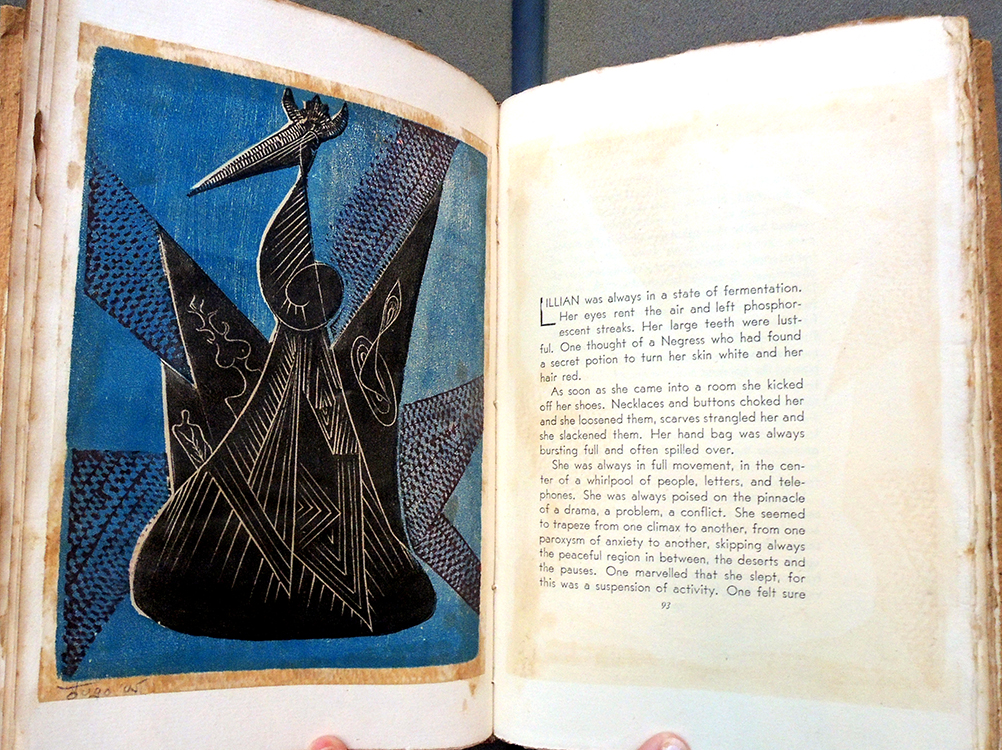

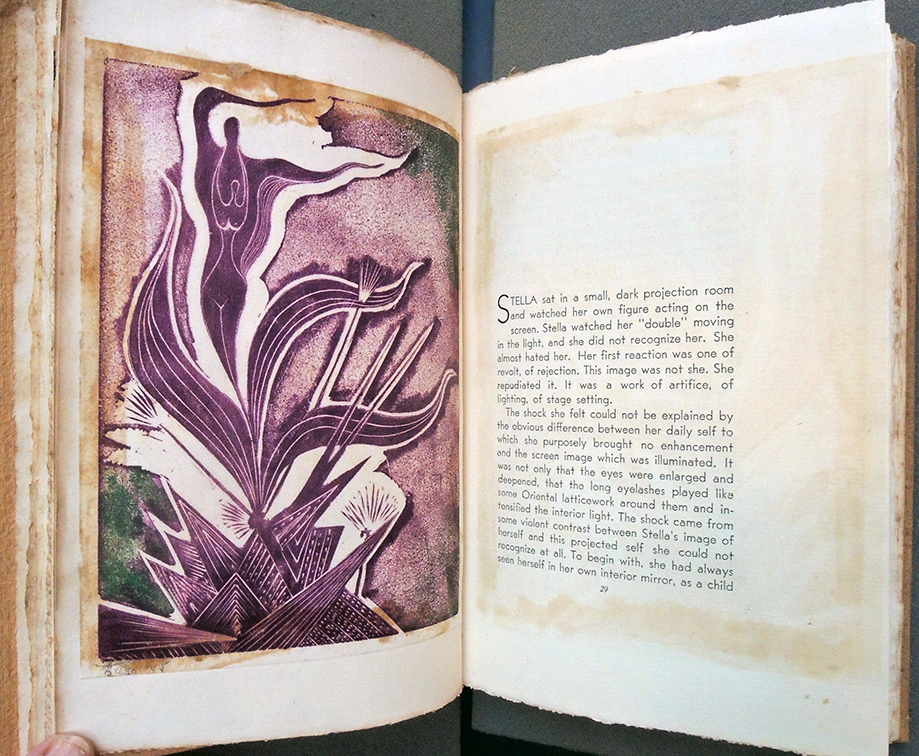

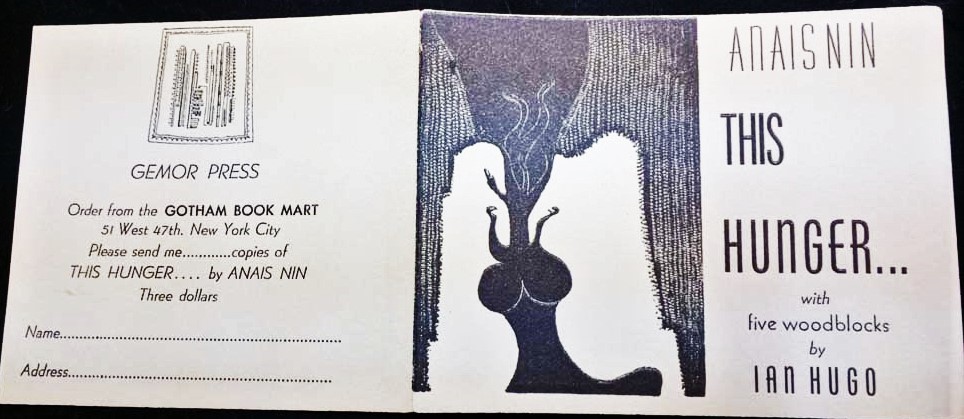

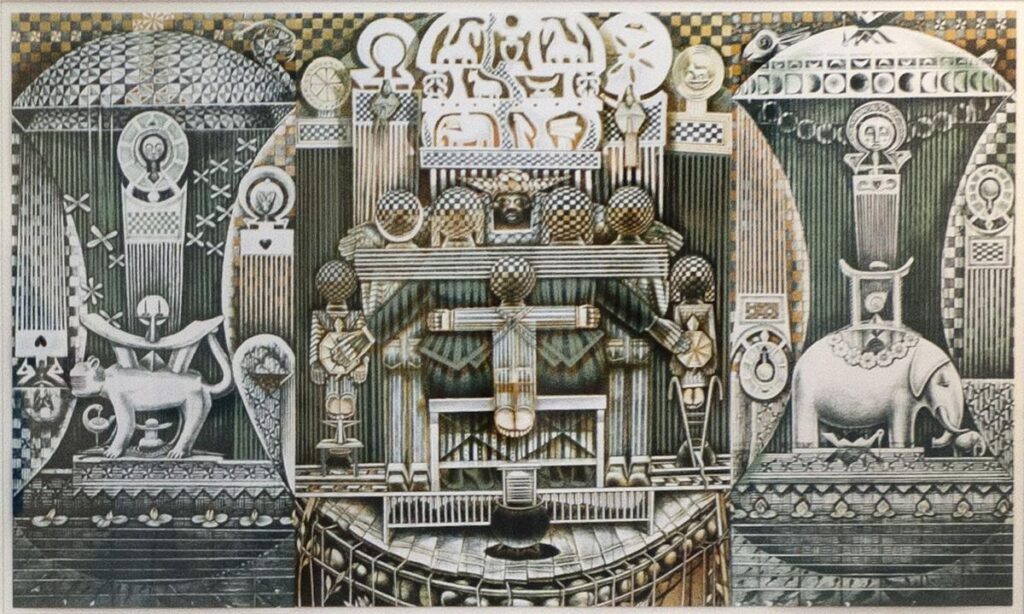

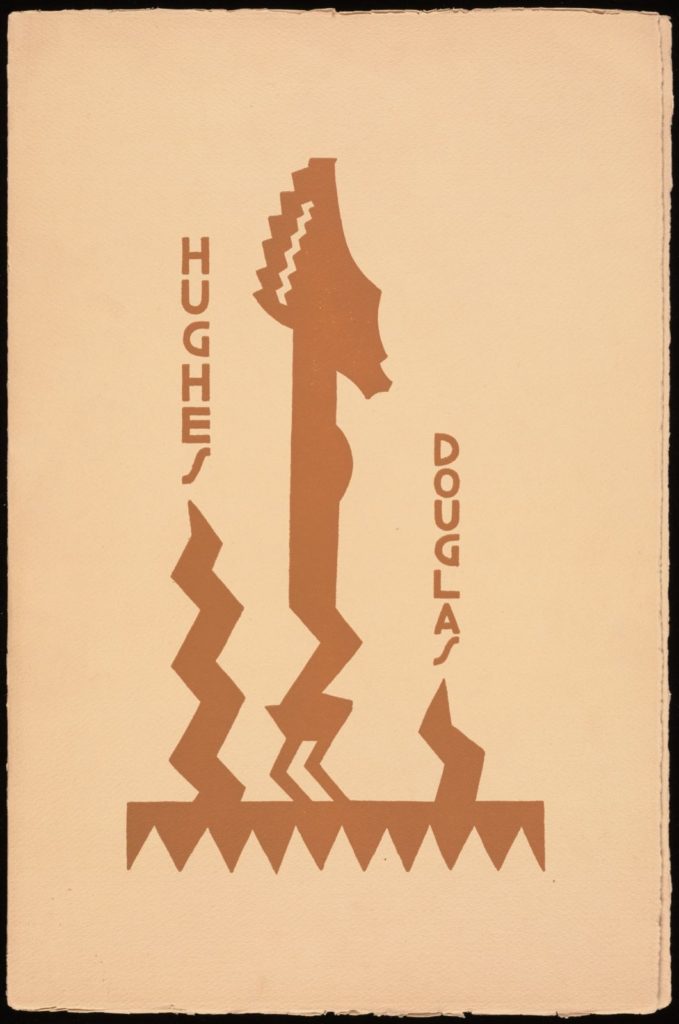

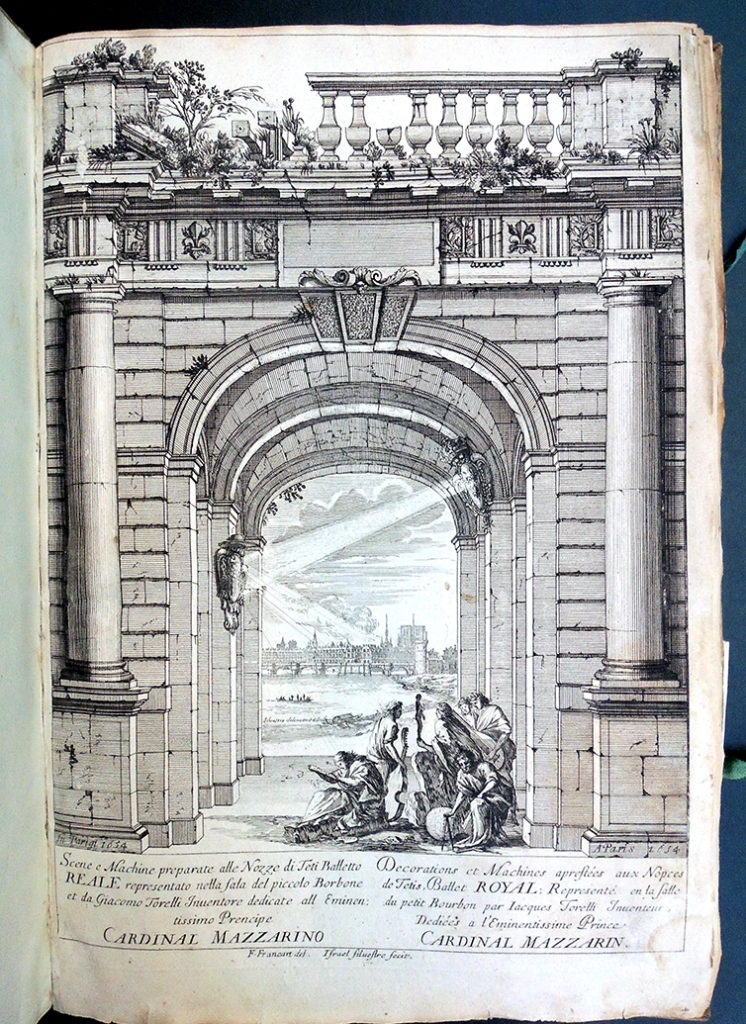

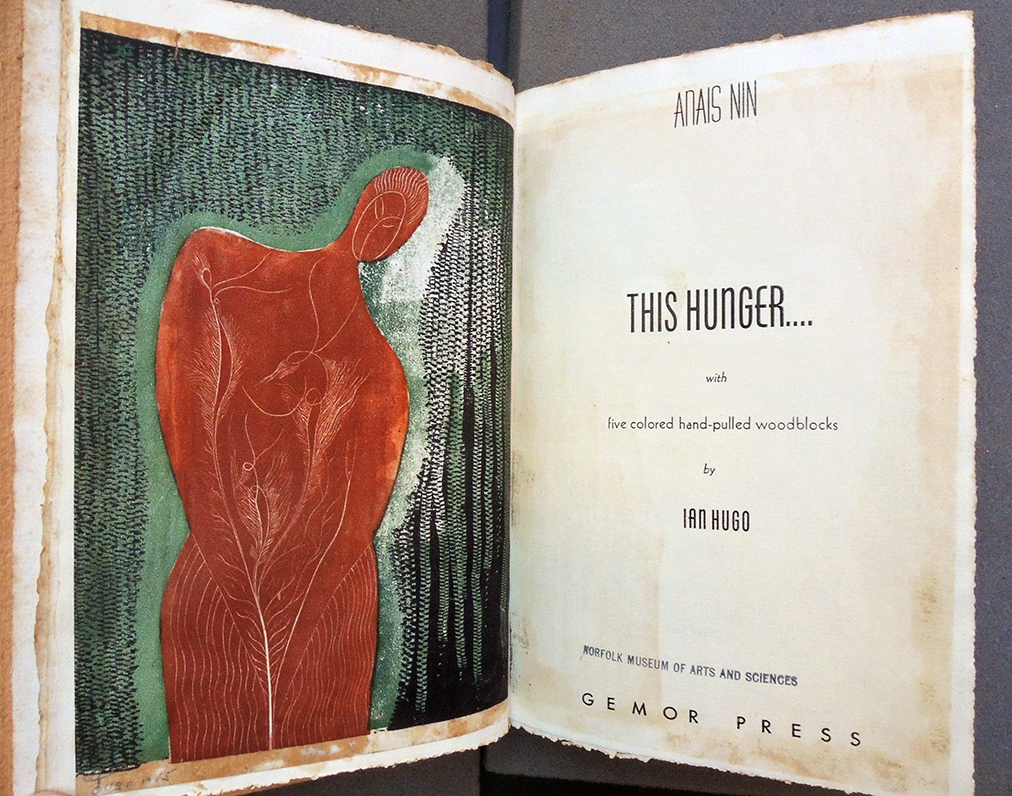

Anaïs Nin (born Neuilly, France, 1903-1977), This Hunger (New York: Gemor Press, 1945). No. 28 of 50 with 5 color woodcuts by Ian Hugo (Hugh Parker Guiler, born Puerto Rico, 1898-1985). Graphic Arts Collection GAX 2020- in process.

Anaïs Nin (born Neuilly, France, 1903-1977), This Hunger (New York: Gemor Press, 1945). No. 28 of 50 with 5 color woodcuts by Ian Hugo (Hugh Parker Guiler, born Puerto Rico, 1898-1985). Graphic Arts Collection GAX 2020- in process.