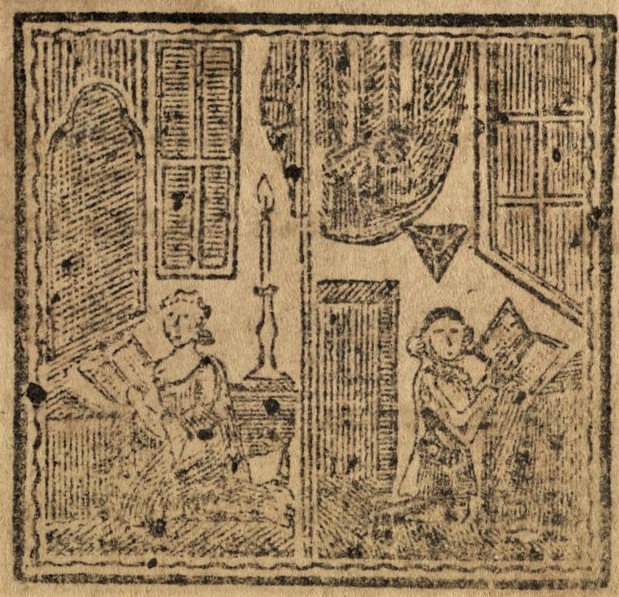

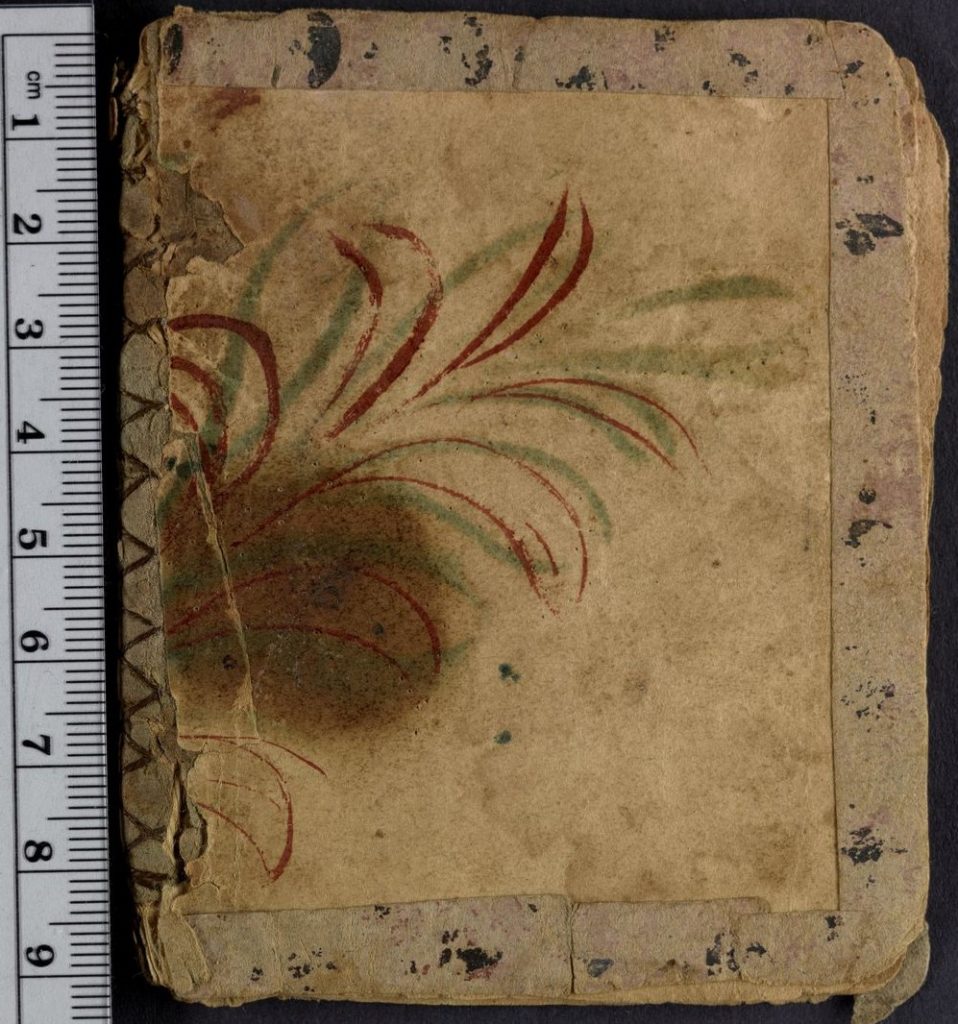

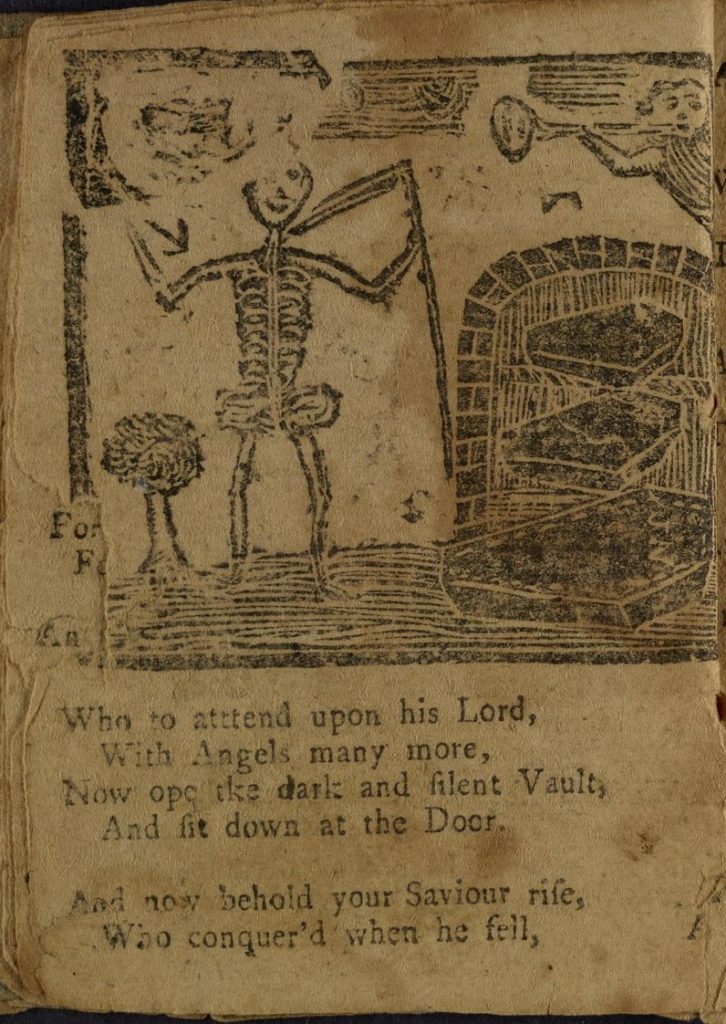

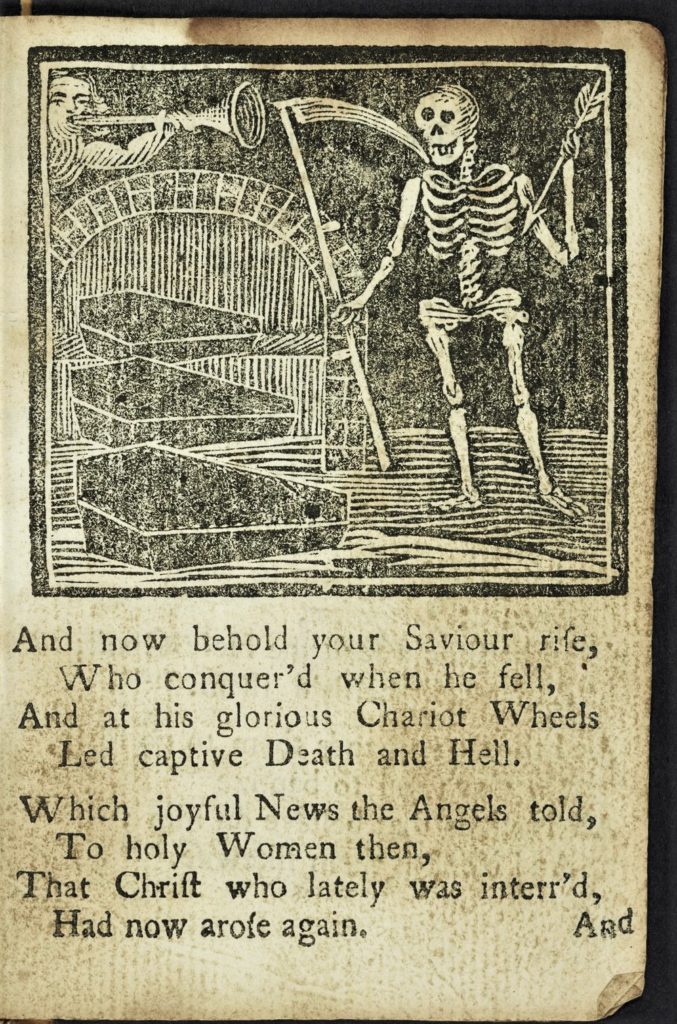

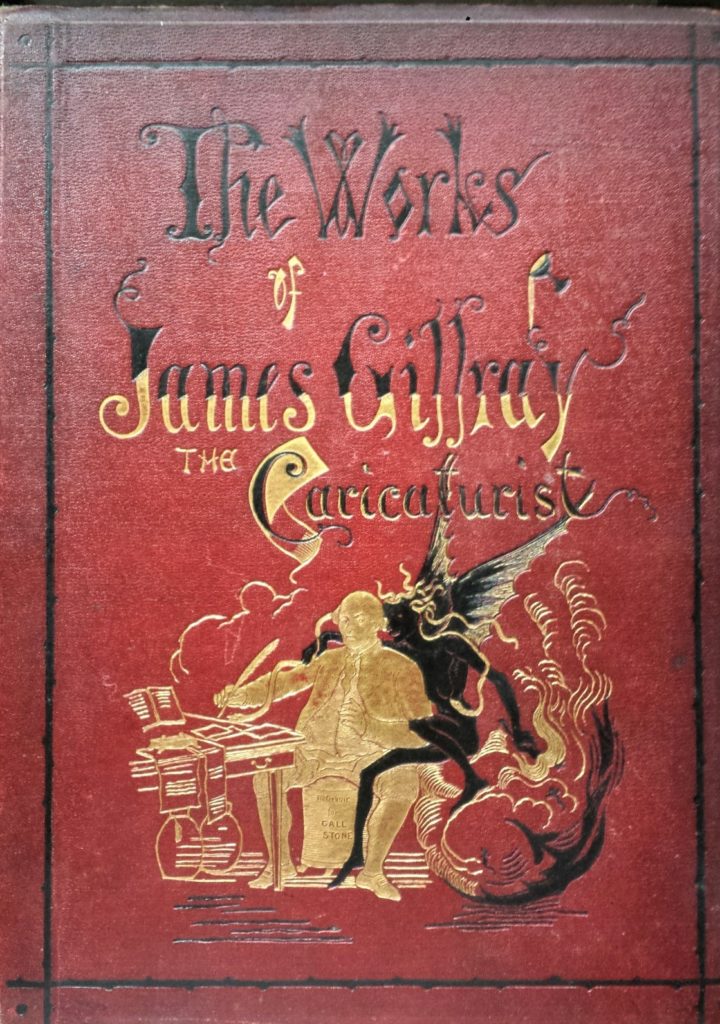

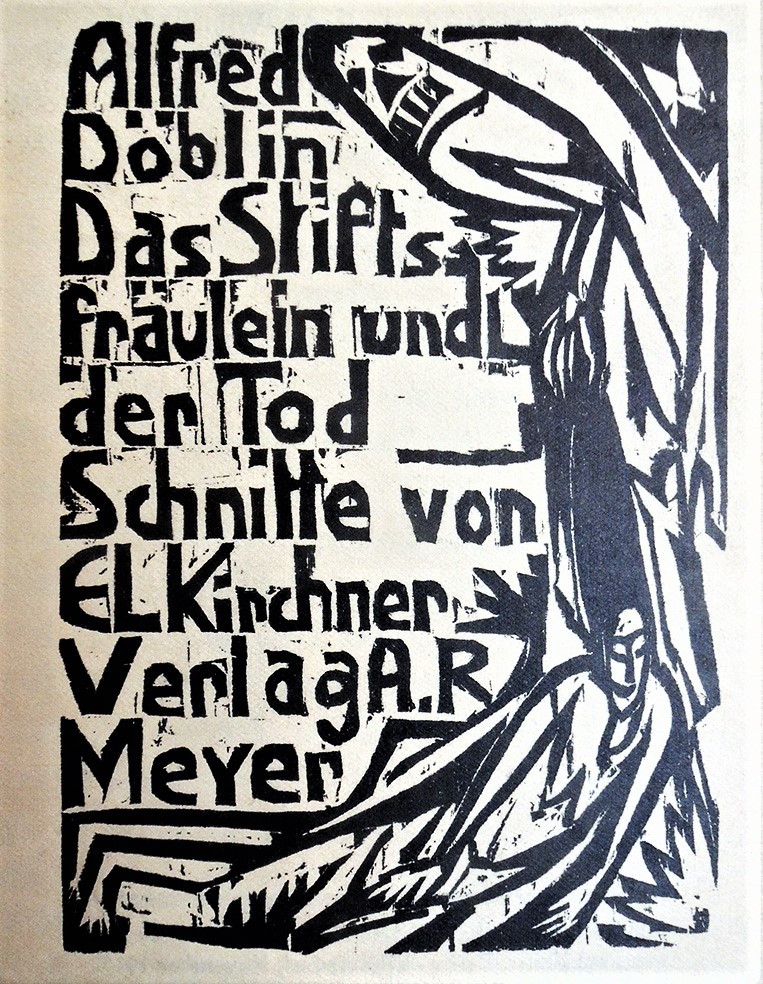

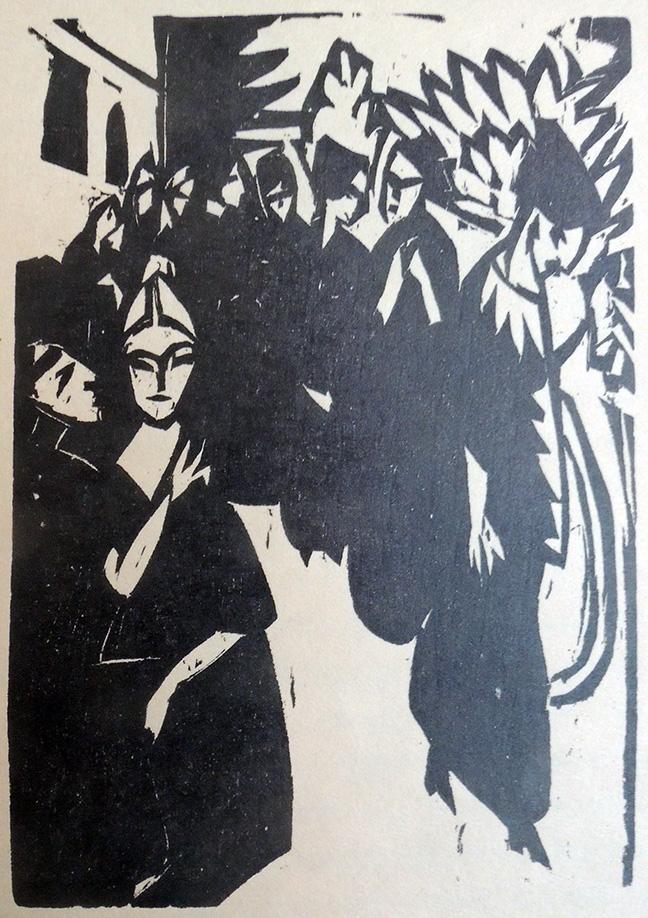

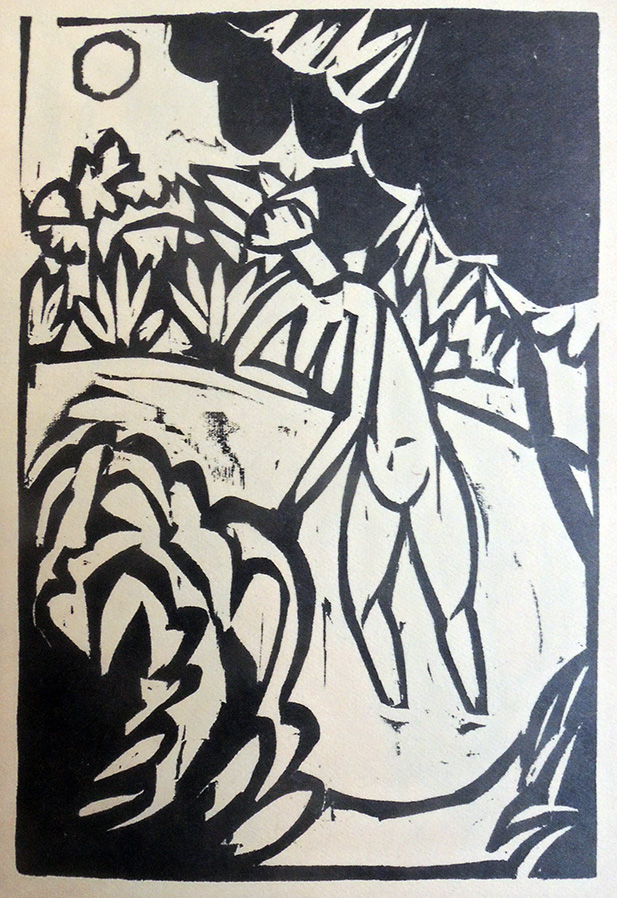

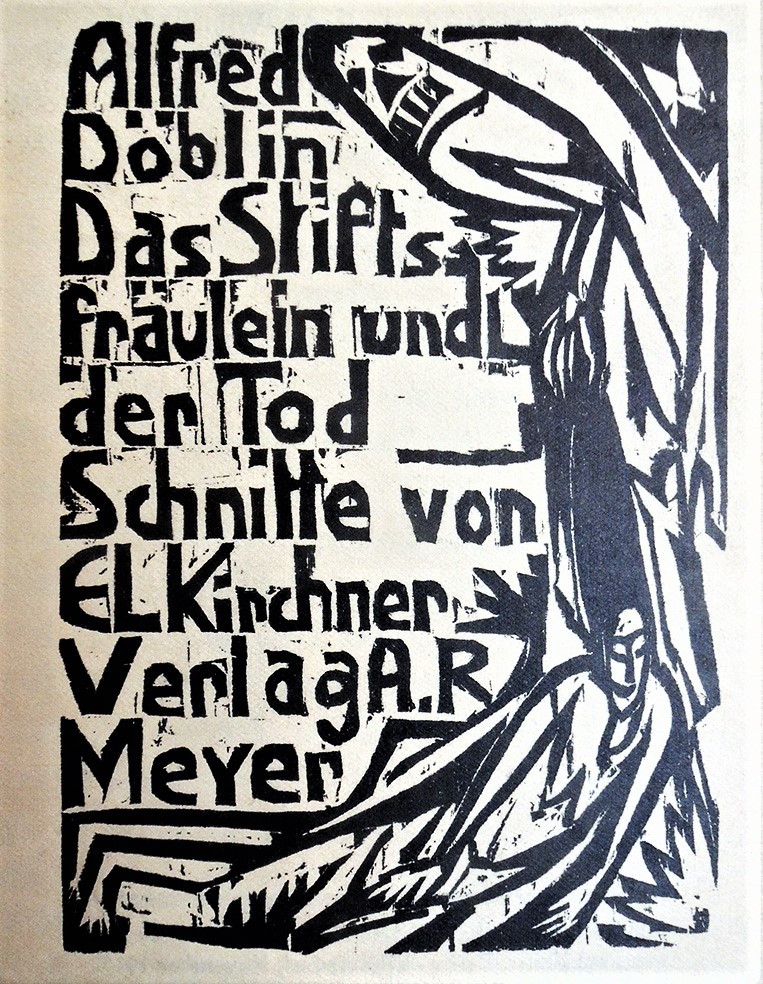

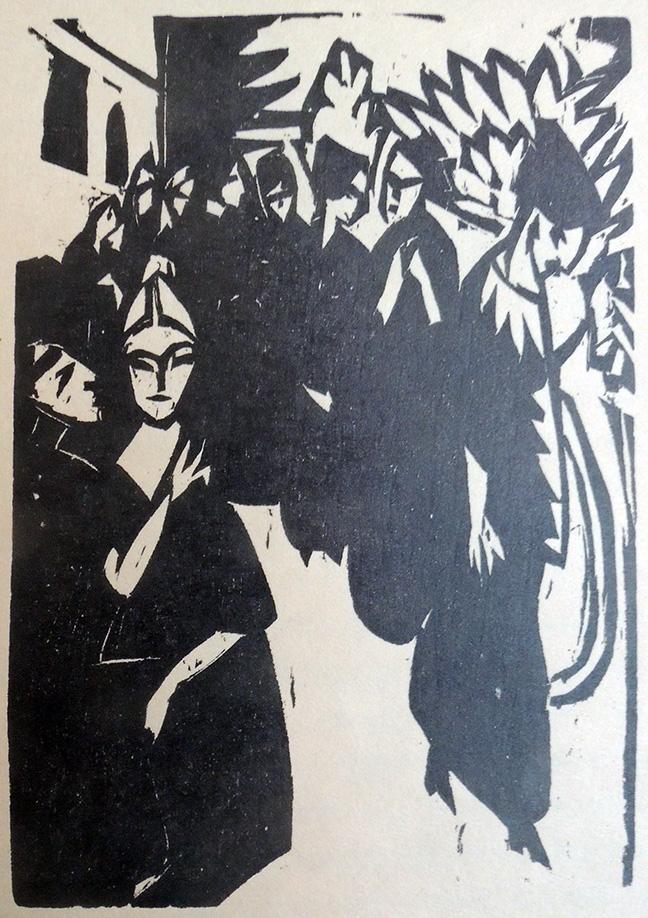

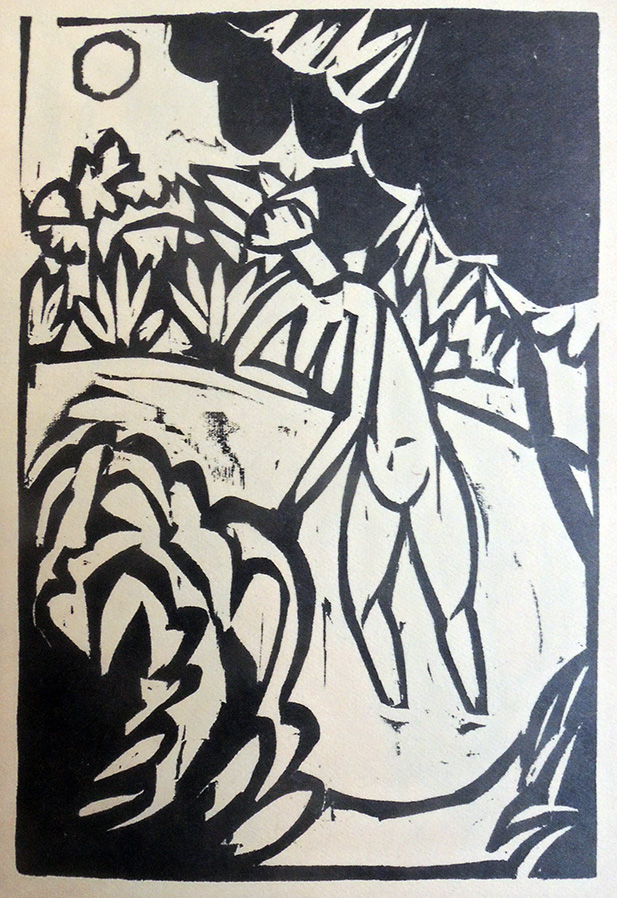

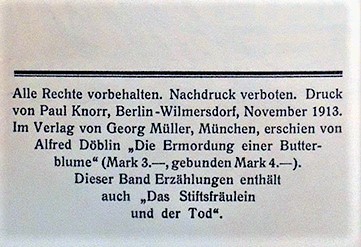

Alfred Döblin (1878-1957) and Ernst Ludwig Kirchner (1880-1938), Das Stiftsfräulein und der Tod: eine Novelle (=The Canoness and Death) (Berlin-Wilmersdorf: A.R. Meyer; printed by Paul Knorr, 1913). Five woodcuts. Graphic Arts Collection 2007-0658N.

Alfred Döblin (1878-1957) and Ernst Ludwig Kirchner (1880-1938), Das Stiftsfräulein und der Tod: eine Novelle (=The Canoness and Death) (Berlin-Wilmersdorf: A.R. Meyer; printed by Paul Knorr, 1913). Five woodcuts. Graphic Arts Collection 2007-0658N.

As a student, Alfred Richard Meyer (1882-1956) made the unusual switch from the study of law to literature and philosophy. He moved to Berlin and joined a circle of intellectuals developing radical new forms of music, theater, painting, and poetry, later known as German Expressionism. Initially Meyer found work at the Otto Janke publishing house and wrote for the Berliner Neueste Nachrichten and the Berliner Allgemeine Zeitung but in 1907 he formed his own publishing company: Alfred Richard Meyer Verlag, Berlin Wilmersdorf.

Years later, Meyer remembered, “It is impossible to imagine our excitement in the evening, when at the Café des Westens or sitting out on the street in front of Gerold’s, at the Gedächtniskirche, we waited for Sturm or Aktion [to appear]. Who was in, who out? The stock market reports were not interesting. We ourselves were the quotations. Who was this new star?”—Stanley Corngold, Franz Kafka (2018).

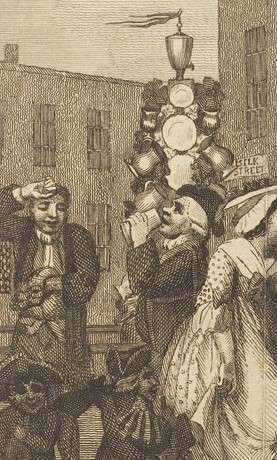

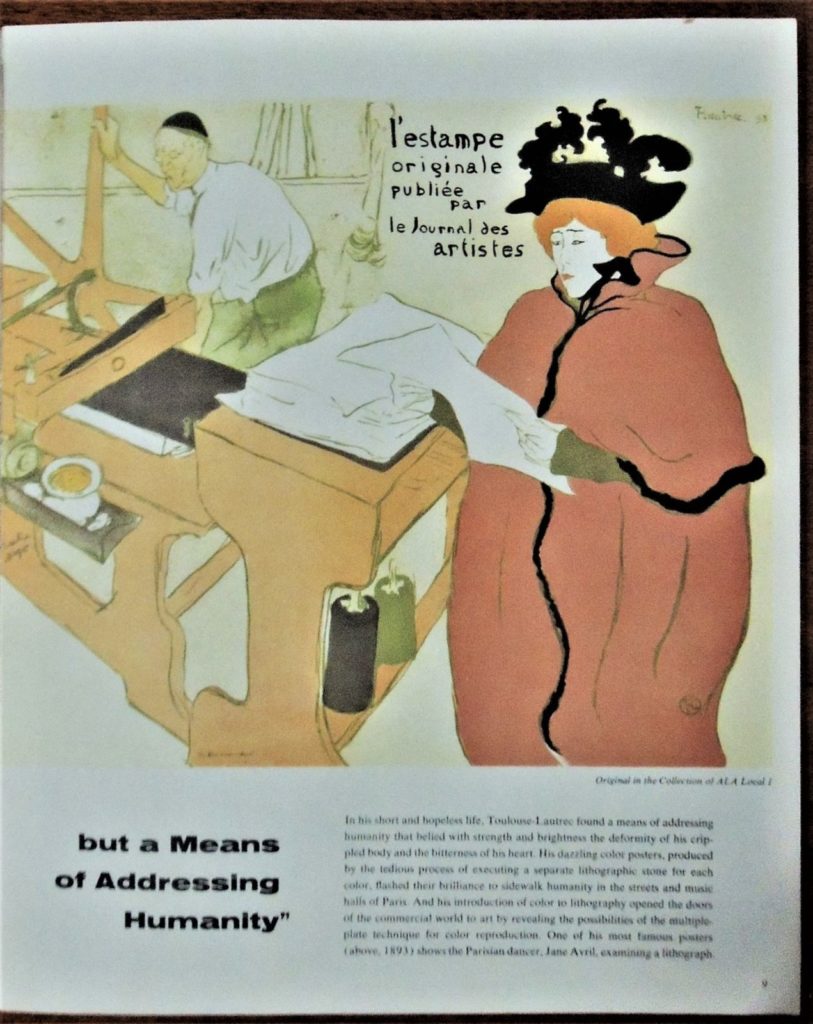

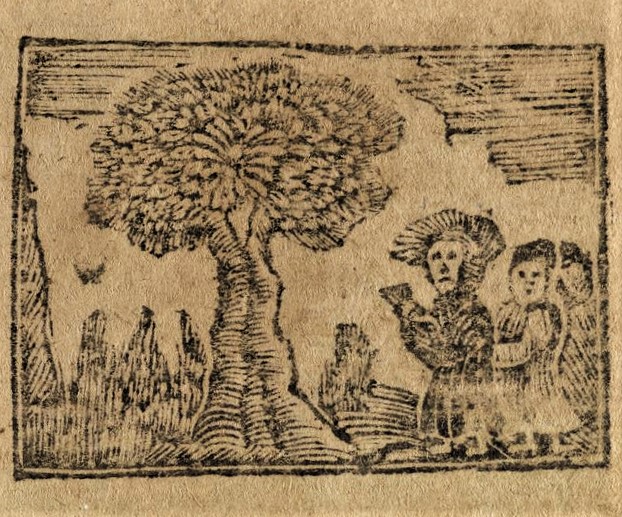

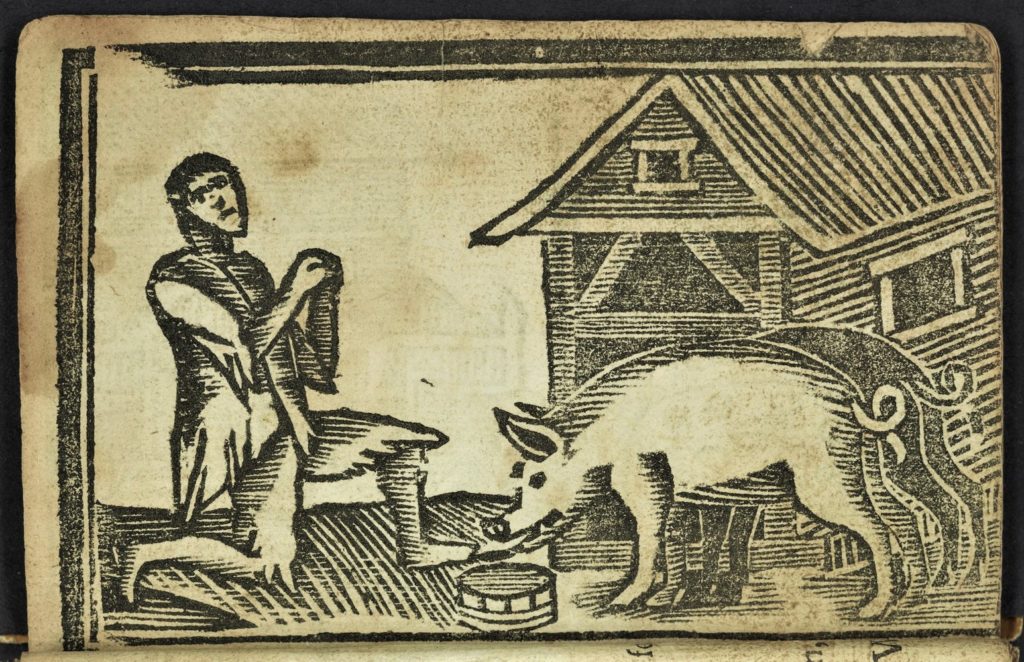

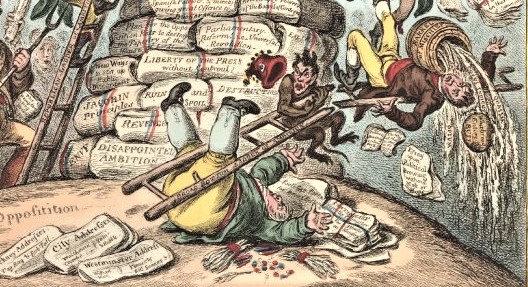

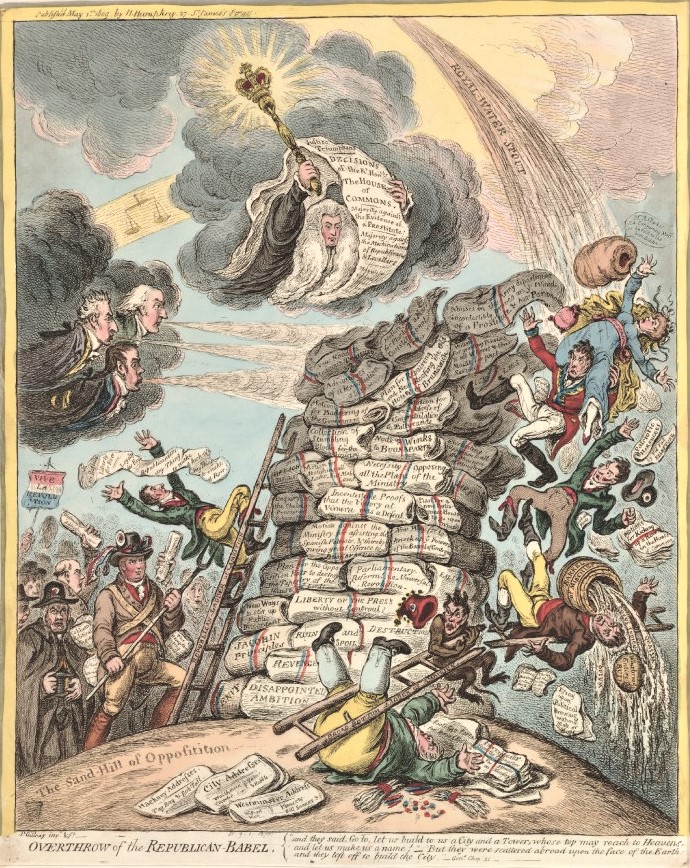

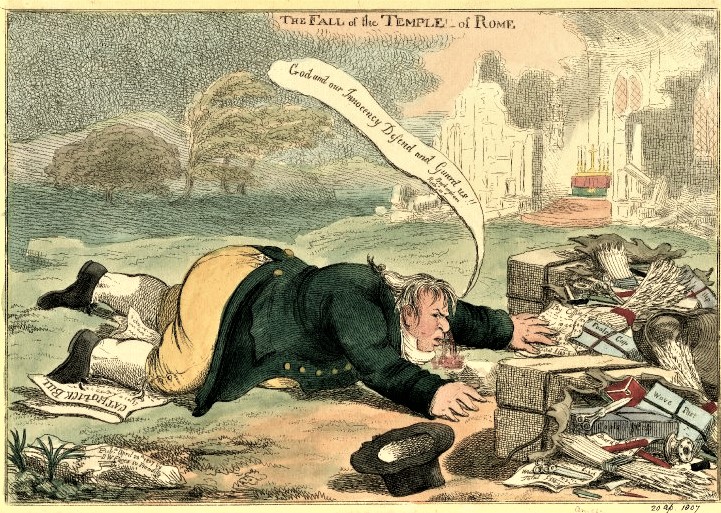

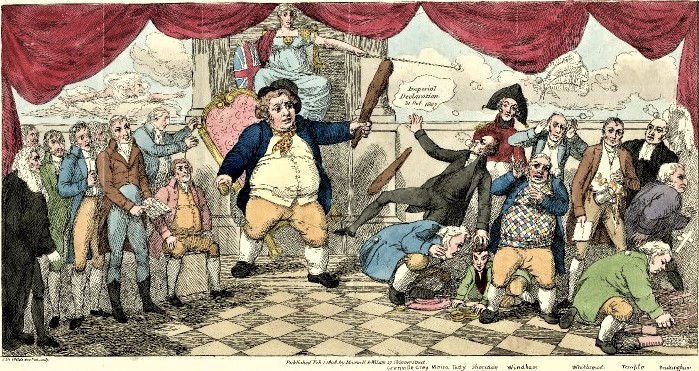

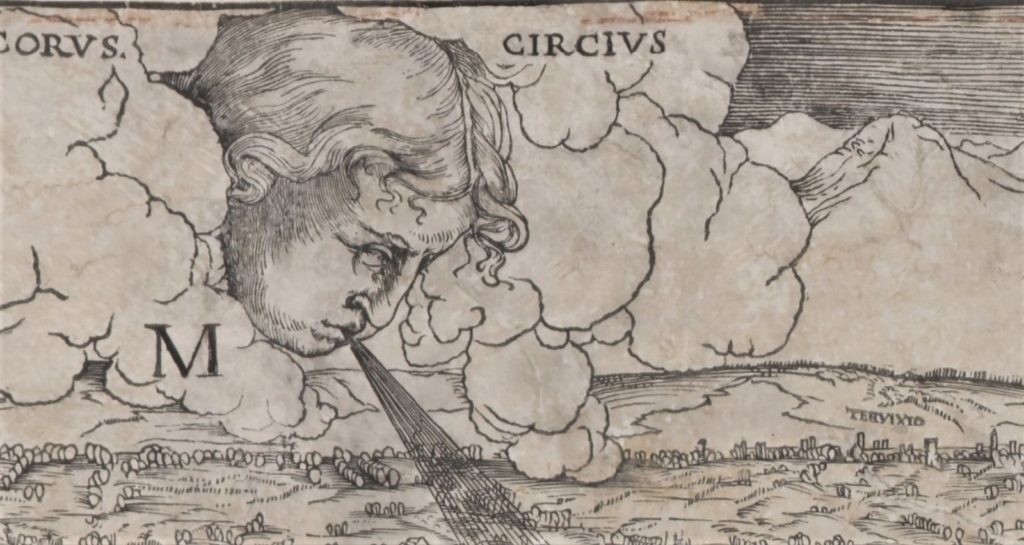

Meyer launched a series a small but seminal publications under the title: Lyrische Flugblätter (Lyrical leaflets) including some of the most important authors of the expressionist period. One of these, Alfred Döblin’s novella Das Stiftsfräulein und der Tod was also the first book that Ernst Ludwig Kirchner (1880-1938) illustrated.

“Kirchner had met Döblin in Berlin in 1912 through Herwarth Walden, the publisher of the avantgarde periodical Der Sturm. Döblin was a psychiatrist by profession but would go on to become one of the most successful writers of the Weimar Republic, best known for his 1929 novel Berlin Alexanderplatz.” https://www.moma.org/collection/works/107155

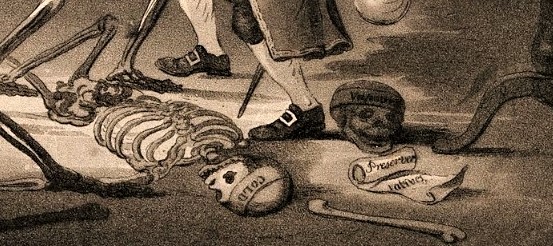

Like Meyer, Kirchner was drawn to Berlin, together with his own circle of artists known as Die Brücke. Around 1912, the group was quarreling (more than usual) and Kirchner looking for other outlets, when he met Alfred Döblin and painted several portraits of the author. They also worked together on a short story about an elderly women living an isolated, monastic life who becomes convinced that she was about to die. Over a tortured few days, her fear increases until “One night, death brutally climbs into her bed and forcibly grabs her body. Her lips were begging. A gag came. The tongue fell back into the throat. She stretched. Then Death got up and pulled the Missus out of the window by her cold hands behind her.”

Among the “Lyrische Flugblätter” series held at Princeton University Library are:

Among the “Lyrische Flugblätter” series held at Princeton University Library are:

1. Hebräische Balladen / von Else Lasker-Schüler. Berlin-Wilmersdorf: A.R. Meyer, [between 1900 and 1999]

2. Ahrenshooper Abende: fünf lyrische Pastelle / von Alfred Richard Meyer. Berlin: Privatdruck der Verfassers, 1907. Cover image by Richard Scheibe.

3. Fünf Gedichte / Heinrich Lautensack. Berlin-Wilmersdorf: A.R. Meyer, 1907.

4. Sechs Sonette: Städte und Menschen / Sophie Hoechstetter. Berlin: A.R. Meyer, 1907.

5. Stella mystica: Traum eines Toren / Hans Carossa; Leo Greiner zugeeignet. Berlin-Wilmersdorf: A.R. Meyer, 1907.

6. Verse / Toni Schwabe. Berlin: A.R. Meyer, 1907.

7. Fünf Gedichte / Ernst Bartels. Berlin: A.R. Meyer, 1907.

8. Jud und Christ, Christ und Jud: ein poetisches Flugblatt / von Heinrich Lautensack. Berlin-Wilmersdorf: A.R. Meyer, 1908.

9. Lieder der Liebe / von Edmund Harst. Berlin-Wilmersdorf: A.R. Meyer, 1908.

10. Lieder eines Knaben / Hans Brandenburg. Berlin-Wilmersdorf: A.R. Meyer, 1908.

11. Rote Nacht: Ballade / von Waldemar Bonsels; für Detlev von Liliencron. Berlin-Wilmersdorf: A.R. Meyer, 1908.

12. Von einer Toten: Herrn und Frau Karl Wolfskehl in Verehrung / Maximilian Brantl. Berlin-Wilmersdorf: A.R. Meyer, 1908.

13. Das frühe Geläut: Gedichte / von Paul Zech, Christ. Gruenewald-Bonn, L. Fahrenkrog, Julius August Vetter. Berlin-Wilmersdorf: A.R. Meyer, 1910.

14. Nasciturs: ein lyrisches Flugblatt / von Alfred Richard Meyer. Berlin-Wilmersdorf: A.R. Meyer, 1910.

15.Wir alarmieren uns: lyrische Funksprüche / von Fritz Wilhelm Schönfeld ; [den Titel zeichnete Bruno Krauskopf]. Berlin: A.R. Meyer, 1910.

16. Felix und Galathea / Frank Wedekind. Berlin-Wilmersdorf: A.R. Meyer, 1911.

17. Die frühe Ernte: Gedichte / von Christian Gruenewald-Bonn. Berlin-Wilmersdorf: A.R. Meyer, 1911.

18. Kleine Balladen / von Leo Sternberg. Berlin-Wilmersdorf: A.R. Meyer, 1911.

19. Das Schlafzimmer: ein neues poetisches Flugblatt / von Heinrich Lautensack.

Berlin-Wilmersdorf: A.R. Meyer, [1911?]

20. Ailleurs / Léon Deubel. Berlin-Wilmersdorf: A.R. Meyer, 1912.

21. Ballhaus: ein lyrisches Flugblatt / von Ernst Blass … [et al.]; mit einem Prolog von Rudolf Kurtz und einem Titelblatt von Walter Roessner. Berlin-Wilmersdorf: A.R. Meyer, [1912]

22. Entelechieen / von Paul Paquita. Berlin-Wilmersdorf: A.R. Meyer, 1912.

23. Die Dämmerung: Gedichte / von Alfred Lichtenstein (Wilmersdorf). Berlin-Wilmersdorf: A.R. Meyer, 1913.

24. Frauen: ein Zyklus Gedichte / von Robert R. Schmidt; in Verehrung für Paul Zech. Berlin-Wilmersdorf: A.R. Meyer, 1913.

25. Rokoko; ein lyrisches Flugblatt anonymer Autoren, von Resi Langer. Berlin; Wilmersdorf, A.R. Meyer [1913]

26. Das schwarze Revier / Paul Zech. Berlin-Wilmersdorf: A.R. Meyer, [1913]. Titelblatt mit Zeichnung von Ludwig Meidner.

27. Das Stiftsfräulein und der Tod / Alfred Döblin; Schnitte von E.L. Kirchner. Berlin-Wilmersdorf: A.R. Meyer, 1913.

28. Und schöne Raubtierflecken–: ein lyrisches Flugblatt / von Ernst Wilhelm Lotz; [das Titelbild zeichnete R. Scheibe, Wilmersdorf]. Berlin-Wilmersdorf: A.R. Meyer, 1913.

29. Leonardo … / Meinke, Hanns. [Pritzwalk, Merlin-presse, 1918]

30. An allegra; gedichte aus dem jahrzehnt 1908-18 … [Pritzwalk] Merlin-presse, 1919.

31. Bibergeil: pedantische Liebeslieder / von Edgar Firn. Berlin: A.R. Meyer, [1919]

32. Wir alarmieren uns: lyrische Funksprüche / von Fritz Wilhelm Schönfeld; [den Titel zeichnete Bruno Krauskopf]. Berlin-Wilmersdorf: A.R. Meyer, [1919?]

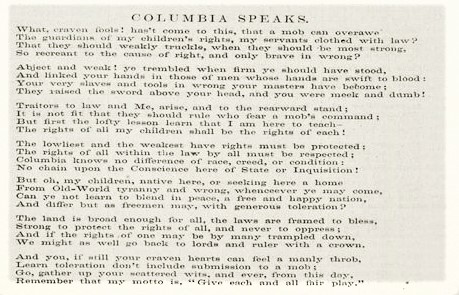

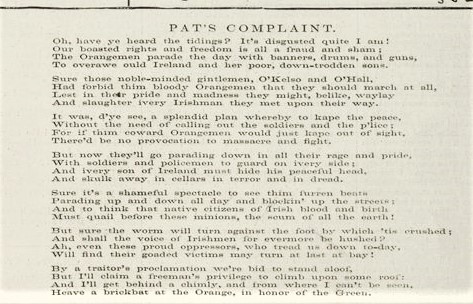

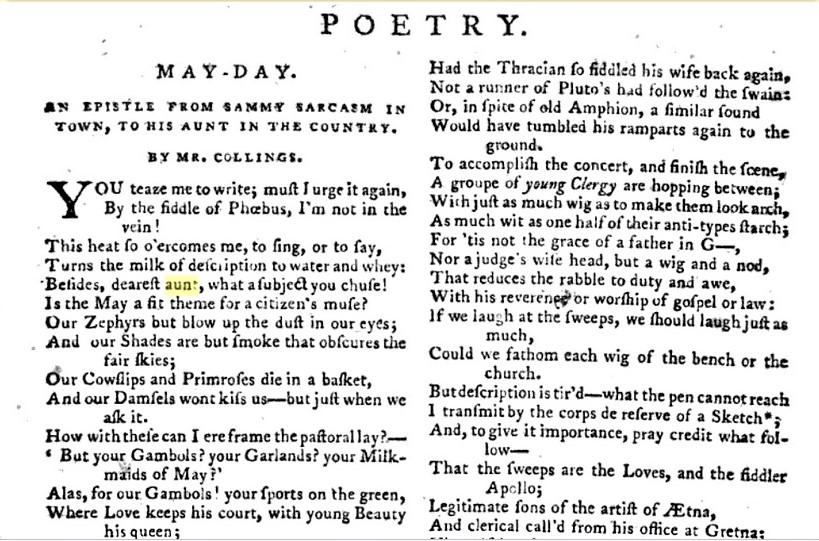

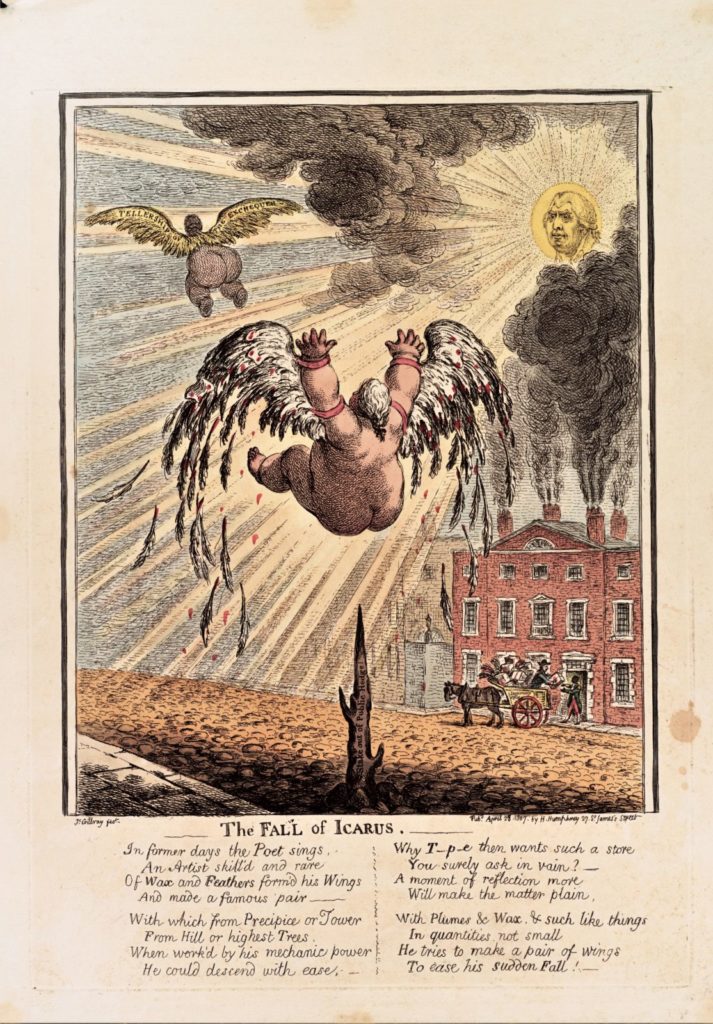

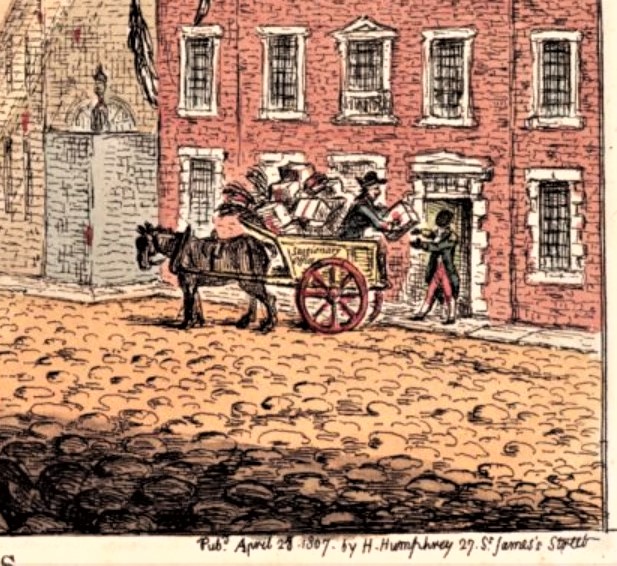

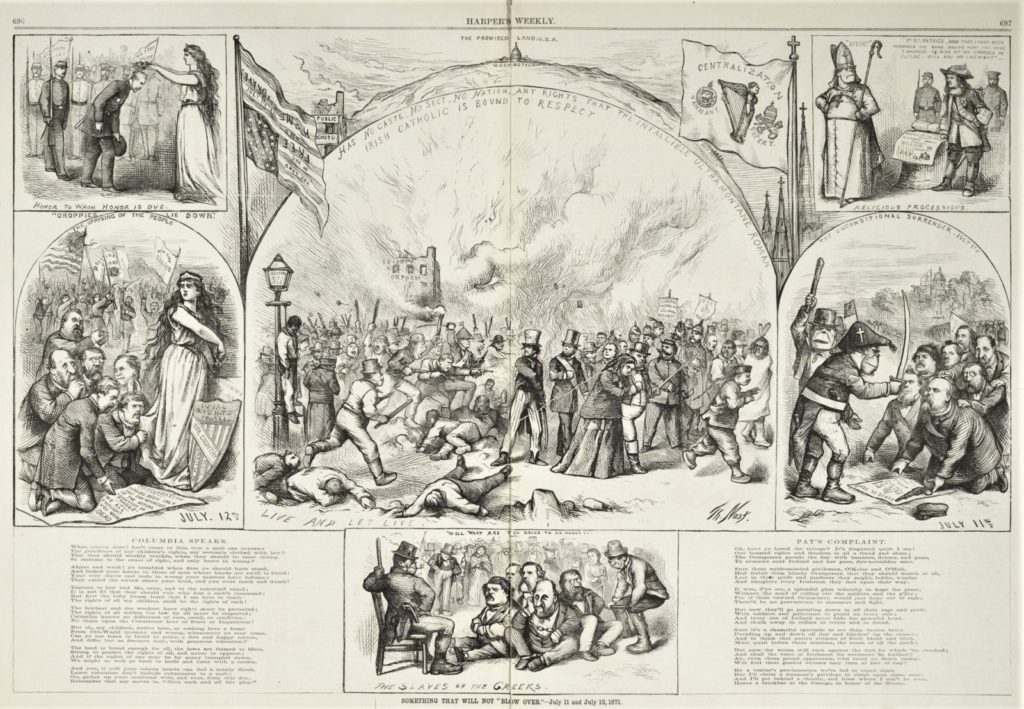

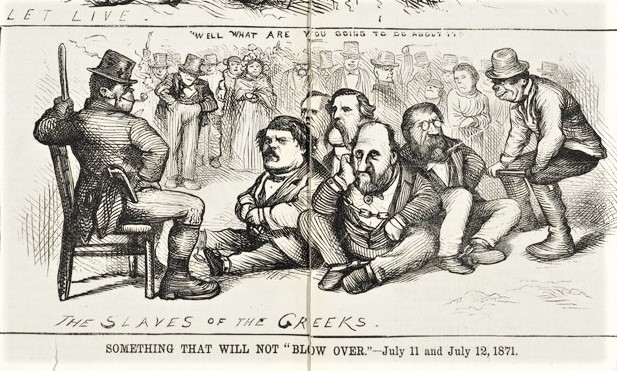

When the Irish Protestant Orange Day parade kicked off on July 12, 1871, in New York City, artist Thomas Nast was one of 5,000 National Guardsmen called out to protect the marchers from hundreds of Irish Catholic protestors. Shots were fired and the resulting Orange Day Riots left 60 civilians and three guardsmen dead, along with many others wounded. Nast recorded a first-hand account in a double-page wood engraving published July 29, 1871 in Harper’s Weekly.

When the Irish Protestant Orange Day parade kicked off on July 12, 1871, in New York City, artist Thomas Nast was one of 5,000 National Guardsmen called out to protect the marchers from hundreds of Irish Catholic protestors. Shots were fired and the resulting Orange Day Riots left 60 civilians and three guardsmen dead, along with many others wounded. Nast recorded a first-hand account in a double-page wood engraving published July 29, 1871 in Harper’s Weekly.

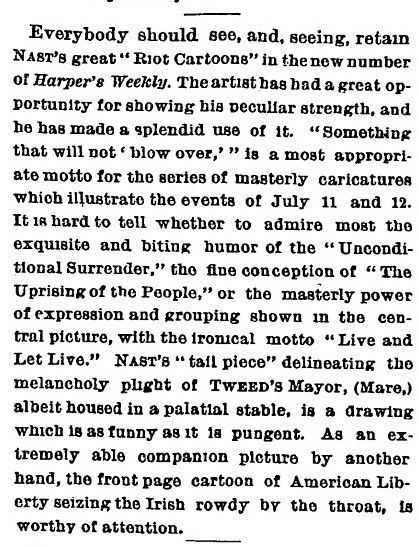

Nast’s work drew such attention that a New York Times editorial was printed, urging readers to see the Harper’s Weekly issue. “Everybody should see, and seeing, retain Nast’s great ‘Riot Cartoons’ on the New Number of Harper’s Weekly.”

Nast’s work drew such attention that a New York Times editorial was printed, urging readers to see the Harper’s Weekly issue. “Everybody should see, and seeing, retain Nast’s great ‘Riot Cartoons’ on the New Number of Harper’s Weekly.”