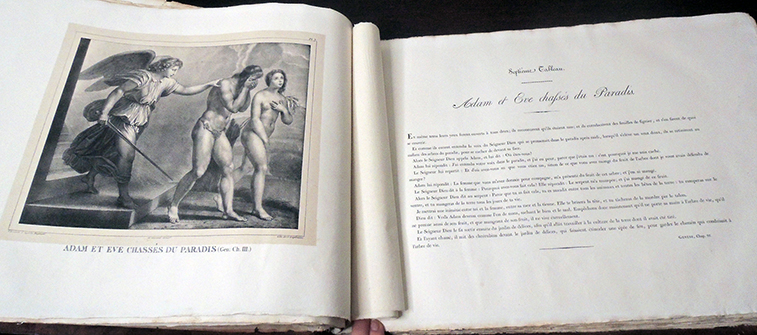

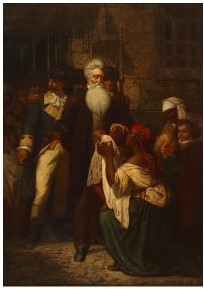

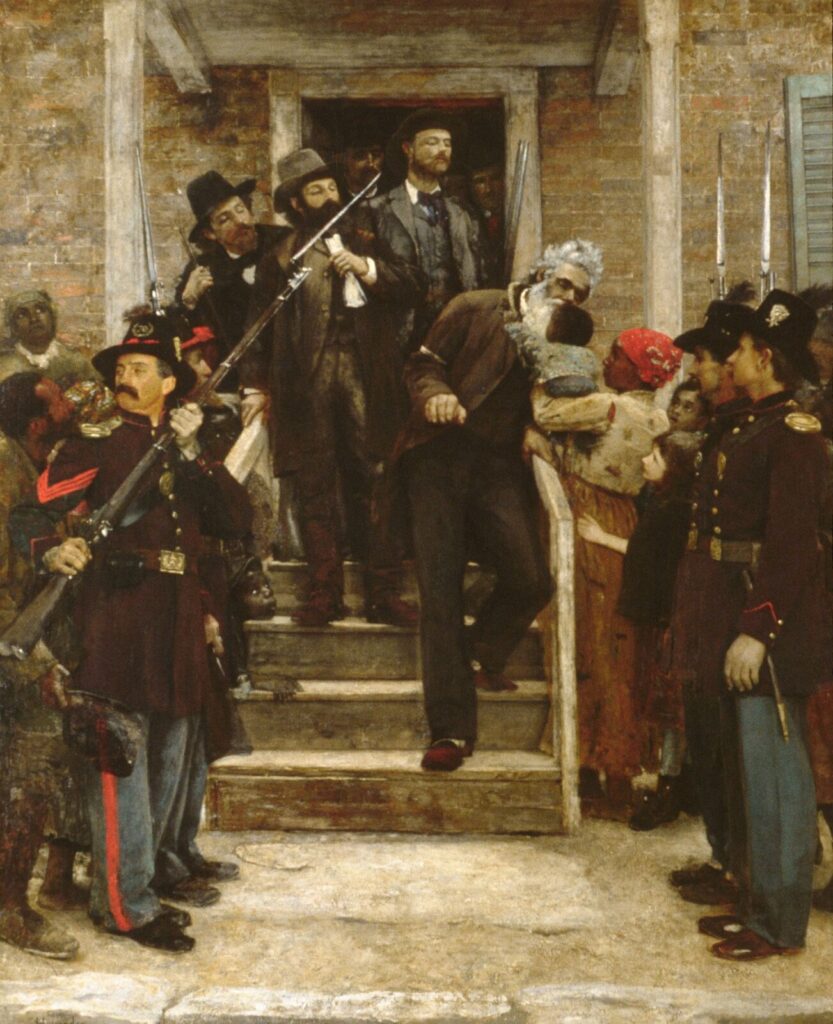

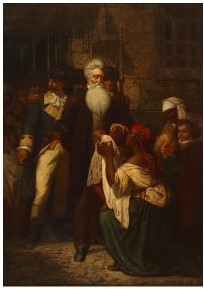

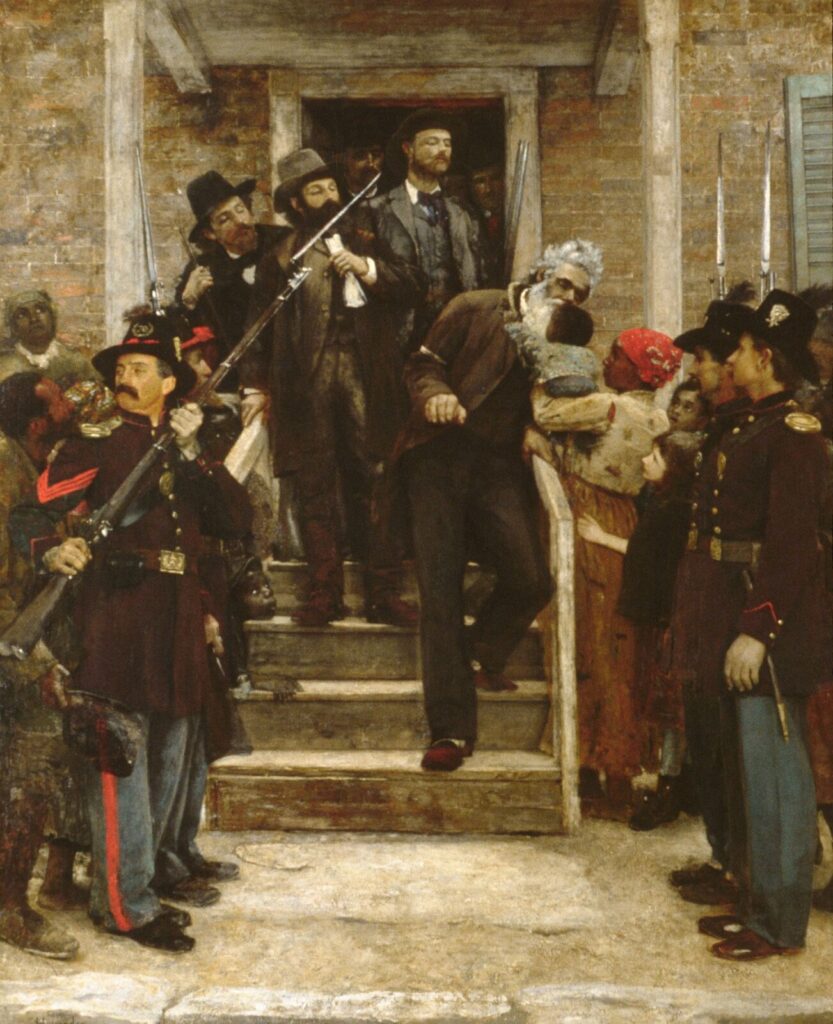

John Brown Meeting the Slave Mother and Her Child on the Steps of Charleston Jail on His Way to Execution, 1863. Published by Currier & Ives. Hand colored lithograph heightened with gum arabic. Graphic Arts Collection GAX 2020- in process

John Brown Meeting the Slave Mother and Her Child on the Steps of Charleston Jail on His Way to Execution, 1863. Published by Currier & Ives. Hand colored lithograph heightened with gum arabic. Graphic Arts Collection GAX 2020- in process

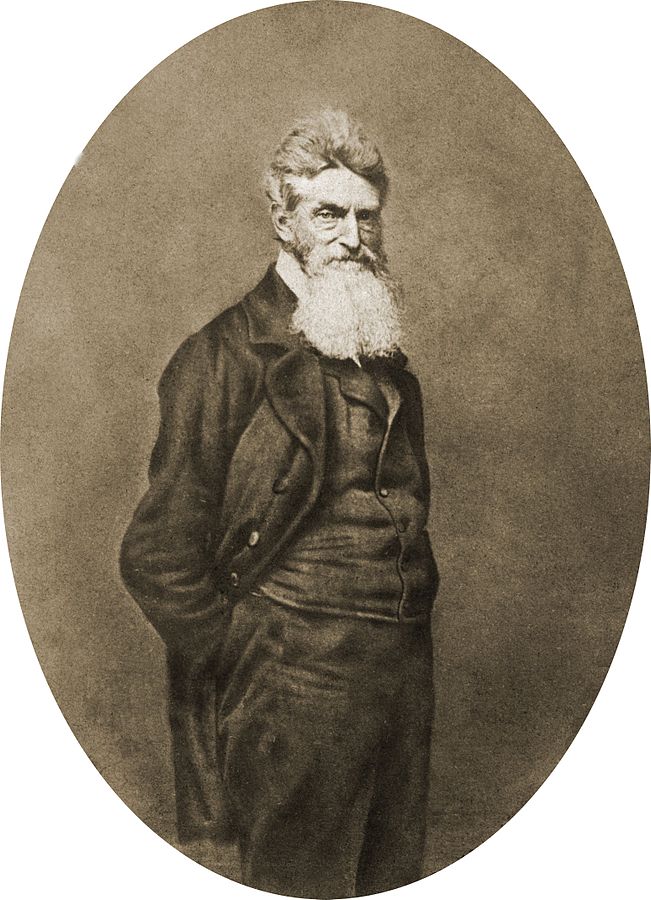

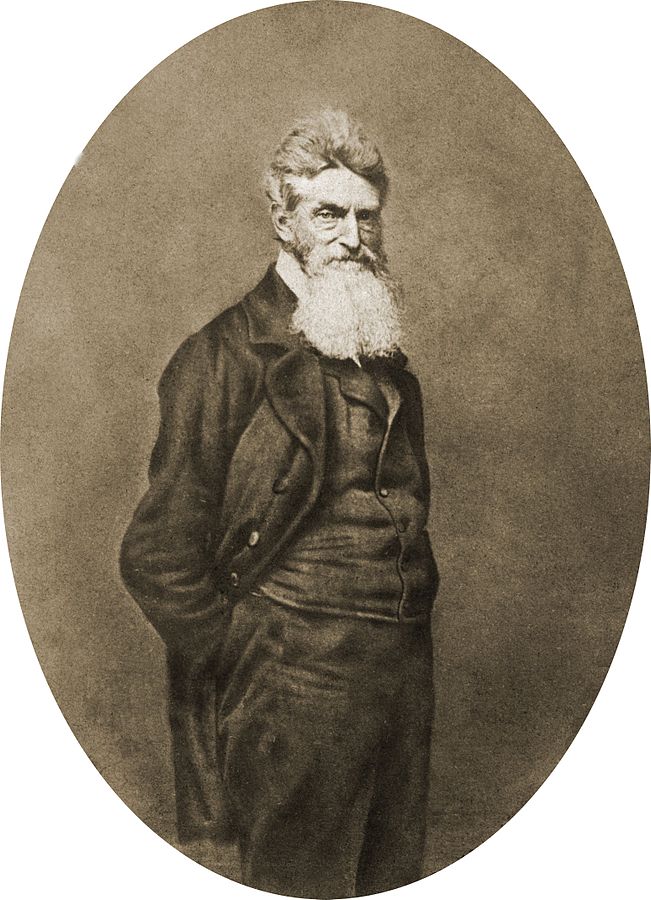

[left] Attributed to Martin M. Lawrence, John Brown in 1859. Salt print, reproduction of daguerreotype. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C.

[left] Attributed to Martin M. Lawrence, John Brown in 1859. Salt print, reproduction of daguerreotype. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C.

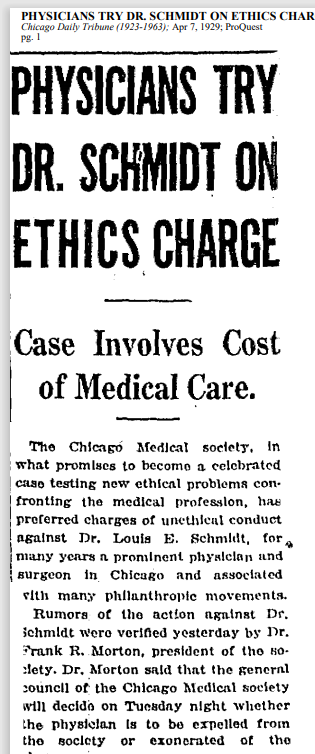

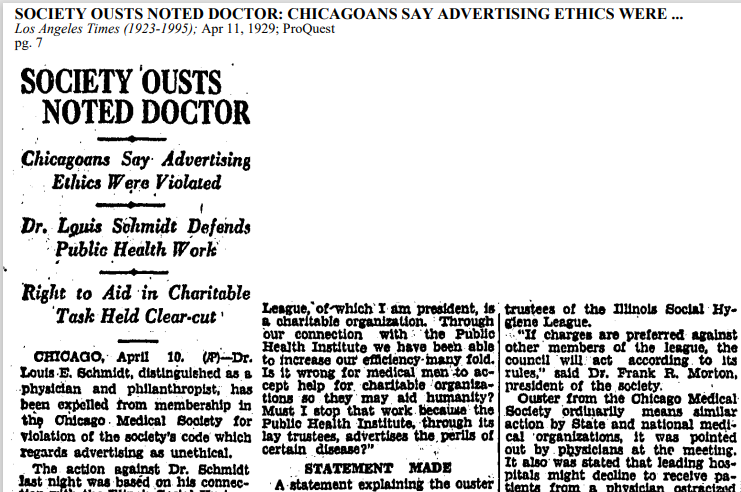

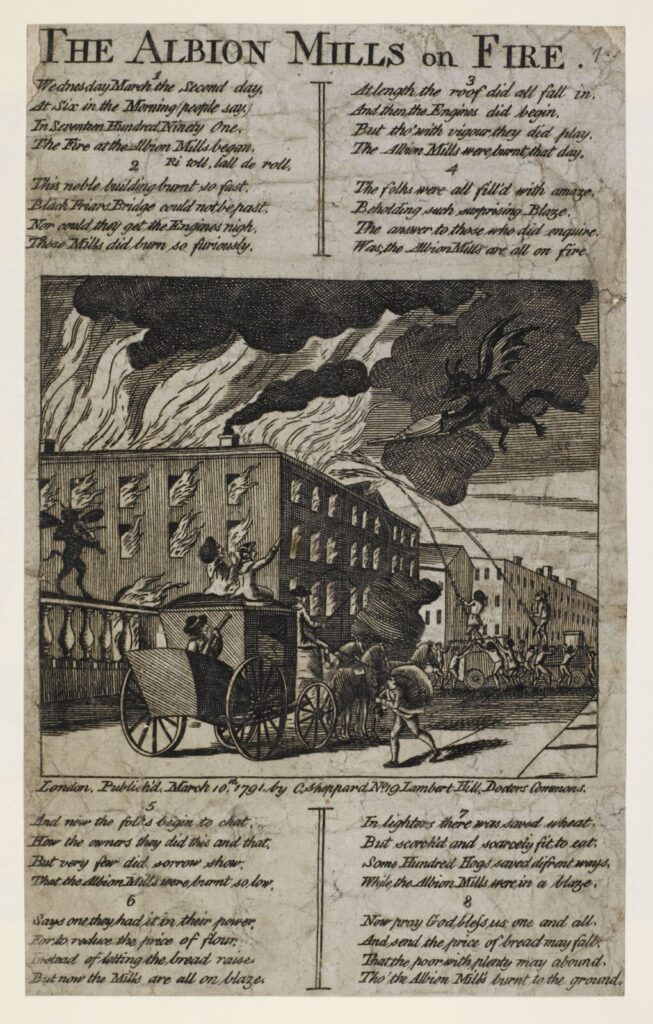

John Brown (1800-1859) led a raid on a federal armory in Harpers Ferry, Virginia (now West Virginia) in October 1859. He was arrested and after a brief trial, convicted and executed by hanging at Charles Town (Charleston), Virginia, on December 2. The anti-slavery New-York Daily Tribune editor Horace Greeley published more than 176 articles on these events, climaxing on December 5, with Edward H. House’s greatly embellished account of Brown’s last day.

“As he [John Brown] stepped out of the door a black woman, with her little child in arms, stood near his way. His thoughts at the moment none can know except as his acts interpret them. He stopped for a moment in his course, stooped over, and with tenderness of one whose love is as broad as the brotherhood of man, kissed it affectionately.”–“John Brown’s Invasion: John Brown’s Remains,” New-York Daily Tribune, December 5, 1859: 5.

This fictional account was reprinted in many other newspapers and in early Brown biographies, as well as in paintings, prints, songs, and poems. The Utica, New York, artist Louis Ransom (1831-1926) was so inspired by House’s story that he began painting a 7 x 10 foot canvas entitled “John Brown on His Way to Execution.” P.T. Barnum was the first to exhibit Ransom’s painting in 1863 at his American Museum in New York City. So incendiary was the scene, and so great was Barnum’s fear of violence due to the New York City draft riots, that he removed the painting in July 1863 (replaced by Tom Thumb).

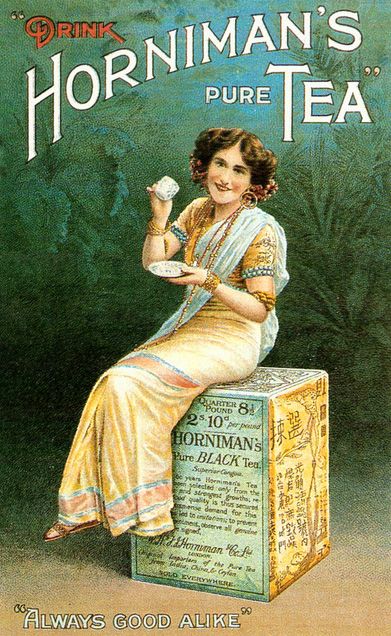

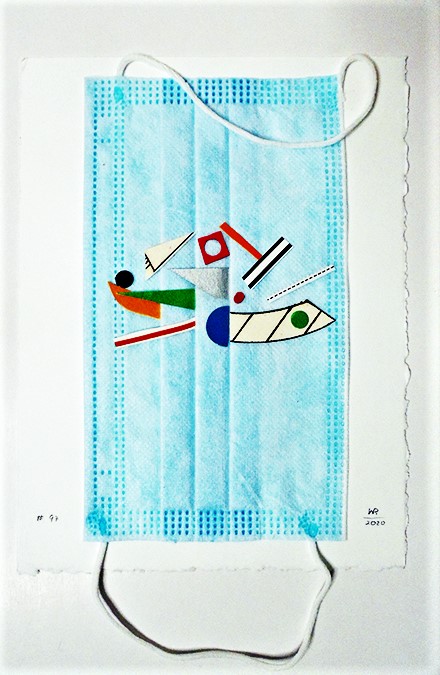

At the same time, two blocks east, the firm of Currier & Ives released a black and white lithograph (priced extra for hand coloring) reproducing Ransom’s painting, entitled John Brown Meeting the Slave Mother and Her Child on the Steps of Charleston Jail on His Way to Execution, 1863 (Gale 3514). Their excellent distribution system placed the print in homes and schools across the United States, where it was accepted as a true account of the events around Brown’s death. Meanwhile Ransom’s painting remained unsold and was eventually given to Oberlin College in exchange for $1.

The poem “Brown of Ossawatomie” by John Greenleaf Whittier (1807-1892) appeared in the New York Independent three weeks after Brown’s death and three years later Thomas Satterwhite Noble (1835-1907) painted John Brown’s Blessing (1867), [currently on view at The New-York Historical Society]. https://www.nyhistory.org/exhibitions/john-brown-the-abolitionist

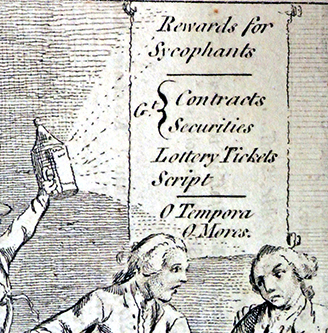

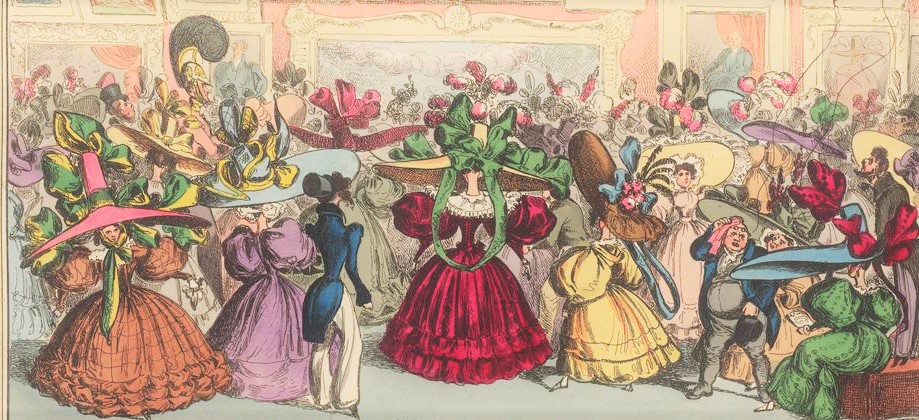

As the Civil War faded in the public conscience Currier & Ives issued a second version of the print in 1870 (Gale 3515), minus its political references [below].

Perhaps the most celebrated of all the artistic scenes was The Last Moments of John Brown (1884) by Thomas Hovenden (1840-1895) and it was the 1885 exhibition of this painting [left] that made historians question the John Brown legend. “How the Story About Kissing the Negro Child Originated,” appeared in New York Sun October 1885, reprinted in Daily Alta California, October 9, 1885, and other papers, reveling or at least confirming that House invented the story published in the Tribune:

“An interesting discussion about an alleged historical incident is now going forward in the columns of the Index of Boston. The question has been mooted before, but it has arisen in the present instance in consequence of a picture painted by Mr. Thomas Hovenden, now on exhibition in Philadelphia. The theme is The Last Moments of Old John Brown and the particular episode represented is that of the old man, while on his way to the scaffold, stooping to kiss a colored child lying in its mother’s arms.”

“…Mr. House was present during the entire trial of John Brown and remained at Charlestown until after the execution. His correspondence was, upon the whole, the most valuable, as it was the most copious that appeared respecting the whole affair. …[but] there was no truth in the published statement of the old man kissing the colored child, and that he (Redpath) had been informed by ” Ned House” that he had ‘invented it.’”

Mr. Edward F. Underhill, who was then attached to the Tribune assigned to the duty of eliciting the occurrences which Mr. McKim had learned, and putting them into the form of correspondence . . . Mr. McKim told the story in question, not as an incident that he had himself seen, for he had not been in Charlestown, but one that he had heard …, had got it by hearsay. …But in 1861 [Underhill] had an opportunity at the Jail in Charlestown of investigating the matter, and was informed by the jailer then in charge that there was no foundation whatever for the story; and he further said that from his own knowledge of the surroundings at the time that it was impossible for the incident to have occurred.”

Published Currier & Ives, 1870.

Published Currier & Ives, 1870.

Brown of Ossawatomie by John Greenleaf Whittier (1807-1892)

John Brown of Ossawatomie spake on his dying day:

‘I will not have to shrive my soul a priest in Slavery’s pay;

But let some poor slave-mother whom I have striven to free,

With her children, from the gallows-stair put up a prayer for me!’

John Brown of Ossawatomie, they led him out to die;

And lo! a poor slave-mother with her little child pressed nigh:

Then the bold, blue eye grew tender, and the old harsh face grew mild,

As he stooped between the jeering ranks and kissed the negro’s child!

The shadows of his stormy life that moment fell apart,

And they who blamed the bloody hand forgave the loving heart;

That kiss from all its guilty means redeemed the good intent,

And round the grisly fighter’s hair the martyr’s aureole bent!

Perish with him the folly that seeks through evil good!

Long live the generous purpose unstained with human blood!

Not the raid of midnight terror, but the thought which underlies;

Not the borderer’s pride of daring, but the Christian’s sacrifice.

Nevermore may yon Blue Ridges the Northern rifle hear,

Nor see the light of blazing homes flash on the negro’s spear;

But let the free-winged angel Truth their guarded passes scale,

To teach that right is more than might, and justice more than mail!

So vainly shall Virginia set her battle in array;

In vain her trampling squadrons knead the winter snow with clay!

She may strike the pouncing eagle, but she dares not harm the dove;

And every gate she bars to Hate shall open wide to Love!

Read more: “The John Brown Legend in Pictures. Kissing the Negro Baby” by James C. Malin in Kansas Historical Quarterlies November, 1940 (Vol. 9, No. 4), pages 339 to 341. https://www.kancoll.org/khq/1939/39_4_malin.htm

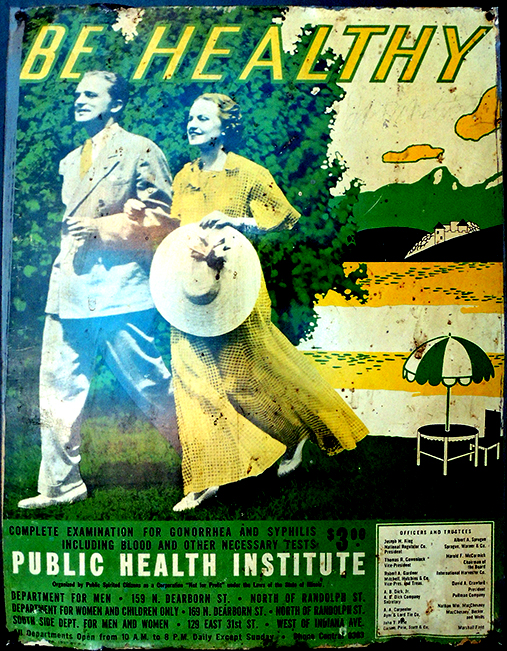

Public Health Institute. Be Healthy. Chicago, 1937. Color enamel silkscreen on metal. Graphic Arts Collection GAX 2020- in process

Public Health Institute. Be Healthy. Chicago, 1937. Color enamel silkscreen on metal. Graphic Arts Collection GAX 2020- in process