Madeline Gins (1941-2014) was an American poet, writer and philosopher. She grew up in Island Park, NY, and graduated from Barnard College in 1962 where she studied physics and philosophy. While studying painting at the Brooklyn Museum Art School in 1962, Gins met Arakawa and she would become one of the primary interpreters of Arakawa’s work.

Madeline Gins (1941-2014) was an American poet, writer and philosopher. She grew up in Island Park, NY, and graduated from Barnard College in 1962 where she studied physics and philosophy. While studying painting at the Brooklyn Museum Art School in 1962, Gins met Arakawa and she would become one of the primary interpreters of Arakawa’s work.

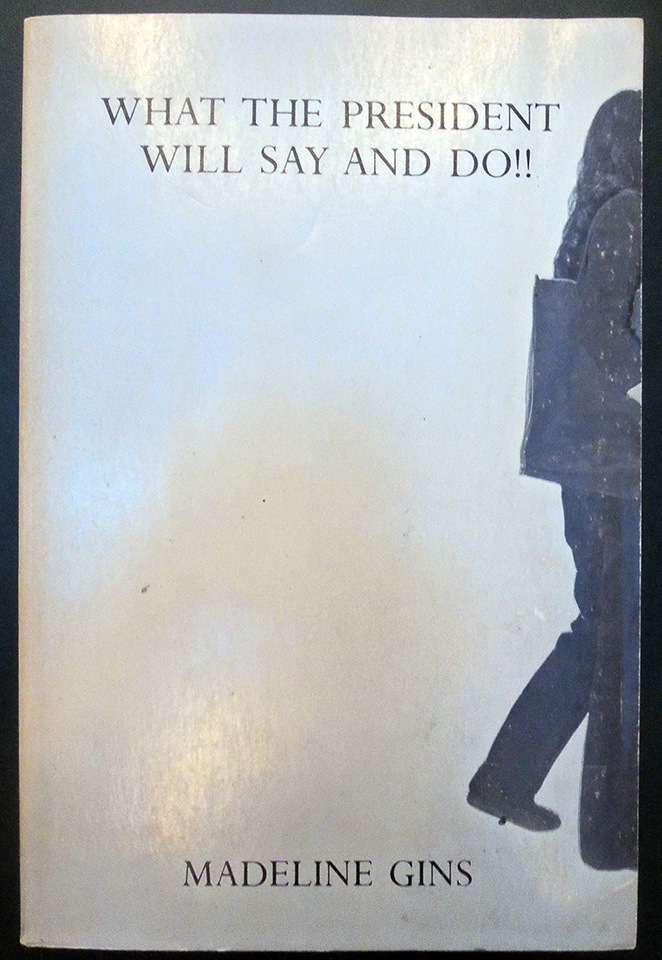

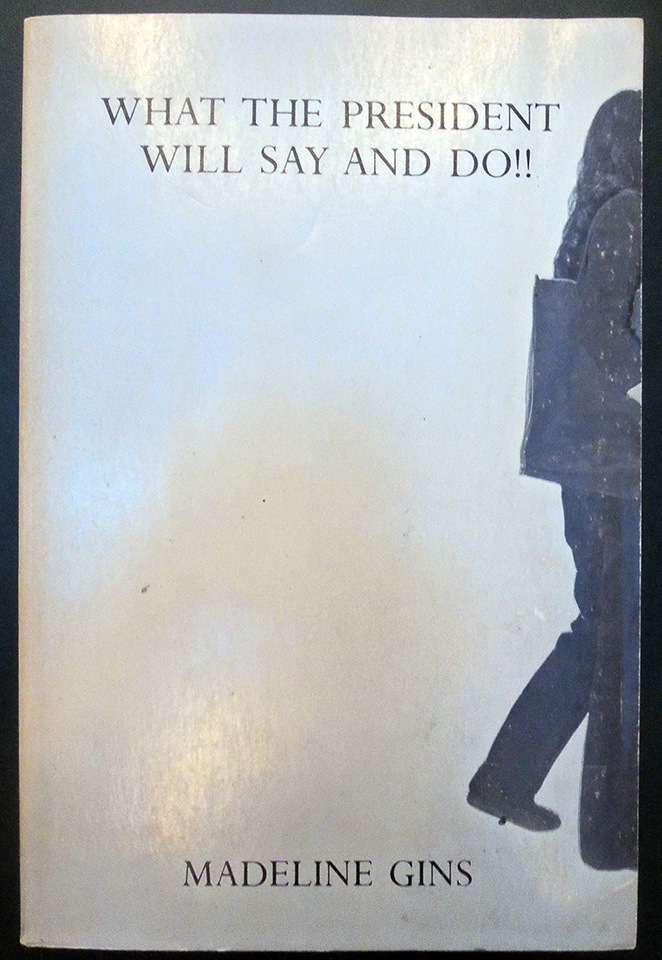

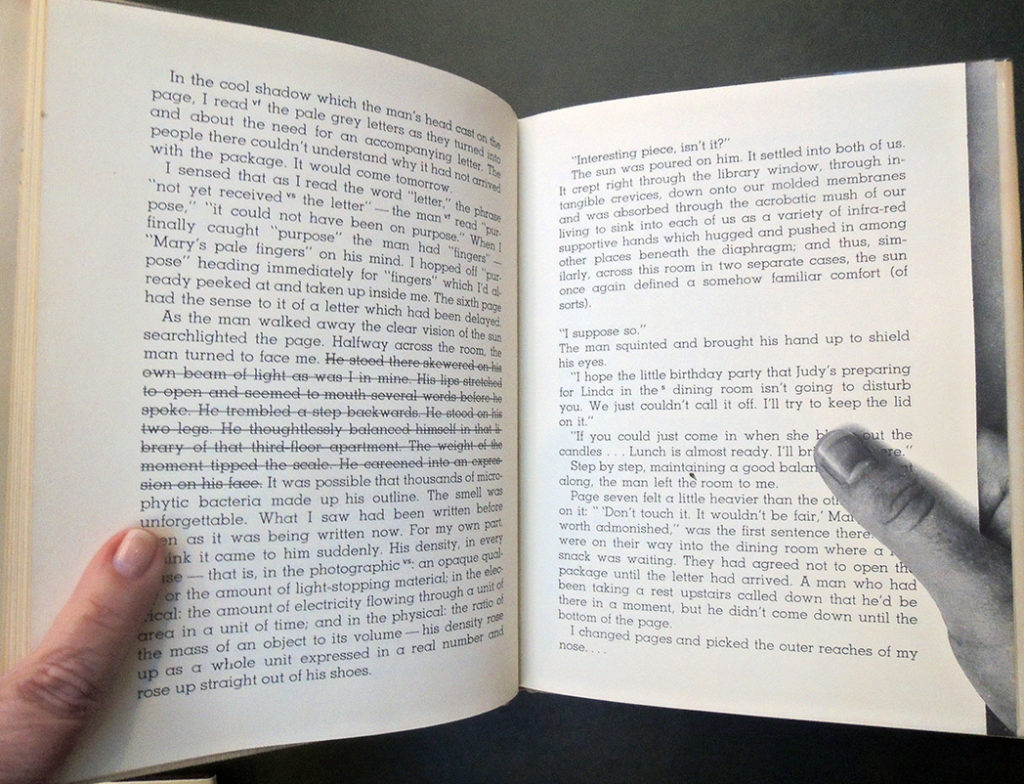

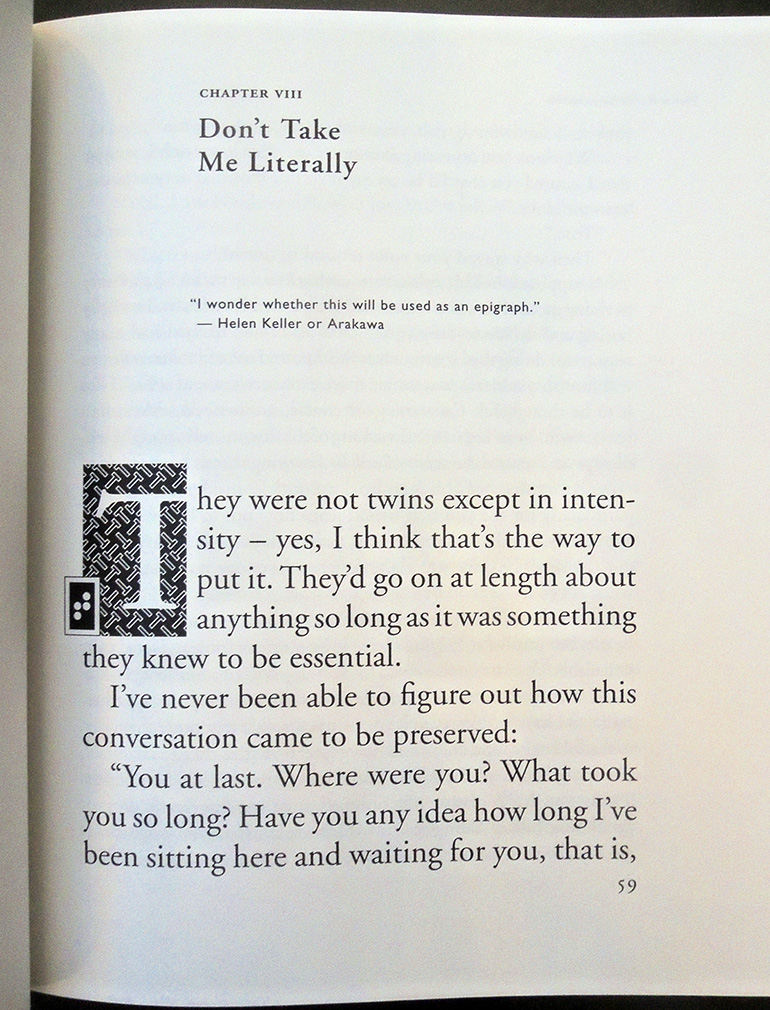

Gins published three books: the experimental novel Word Rain (or a Discursive Introduction to the Intimate Philosophical Investigations of G,R,E,T,A, G,A,R,B,O, It Says) (New York: Grossman Publishers, 1969); What The President Will Say and Do!! (New York: Station Hill, 1984), an excursion into identity, language and free speech using the devices of political rhetoric; and Helen Keller or Arakawa (Santa Fe: Burning Books with East/West Cultural Studies, 1994), an art-historical novel that took on a form of speculative fiction.

With Arakawa, Gins developed the philosophy of ‘procedural architecture’ to further its impact on human lives. These ideas were explored through three books that she co-authored with Arakawa: Pour ne Pas Mourir/To Not to Die (Éditions de la Différence, Paris 1987); Architectural Body (University of Alabama Press, 2002); and Making Dying Illegal – Architecture Against Death: Original to the 21st Century (Roof Books, New York, 2006). …Gins also completed the manuscript for Alive Forever and the illustrated version of her poem Krebs Cycle.–http://www.reversibledestiny.org/arakawa-and-madeline-gins/madeline-gins

http://www.reversibledestiny.org/arakawa-and-madeline-gins/madeline-gins/bibliography1

http://www.reversibledestiny.org/arakawa-and-madeline-gins/madeline-gins/bibliography1

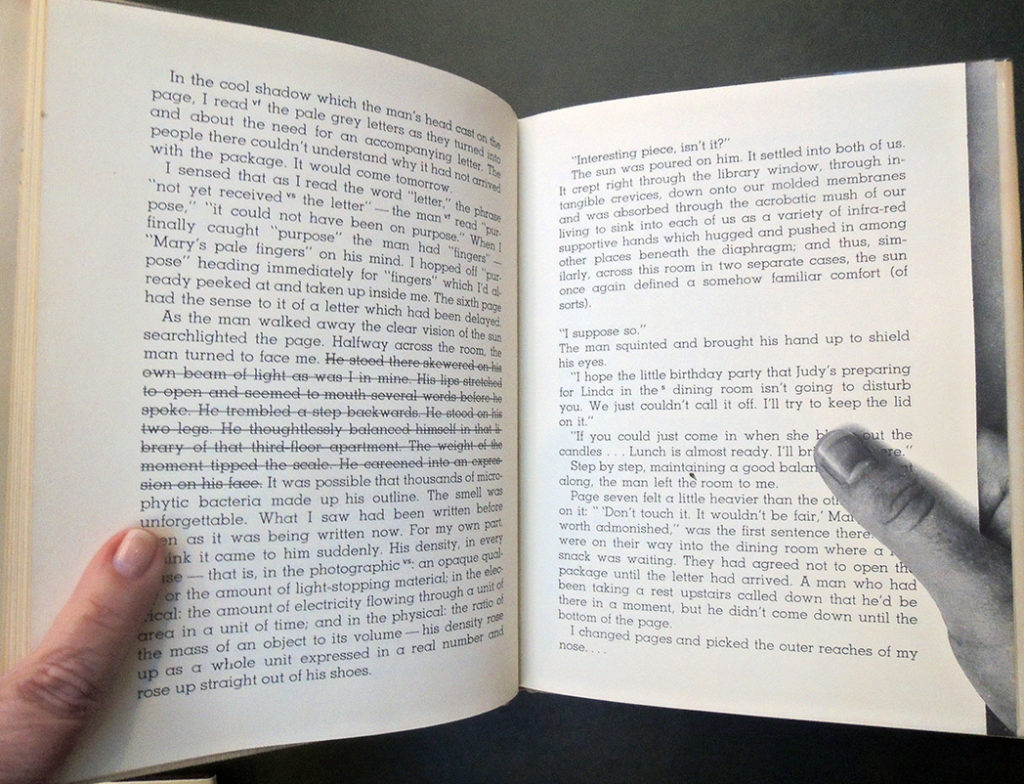

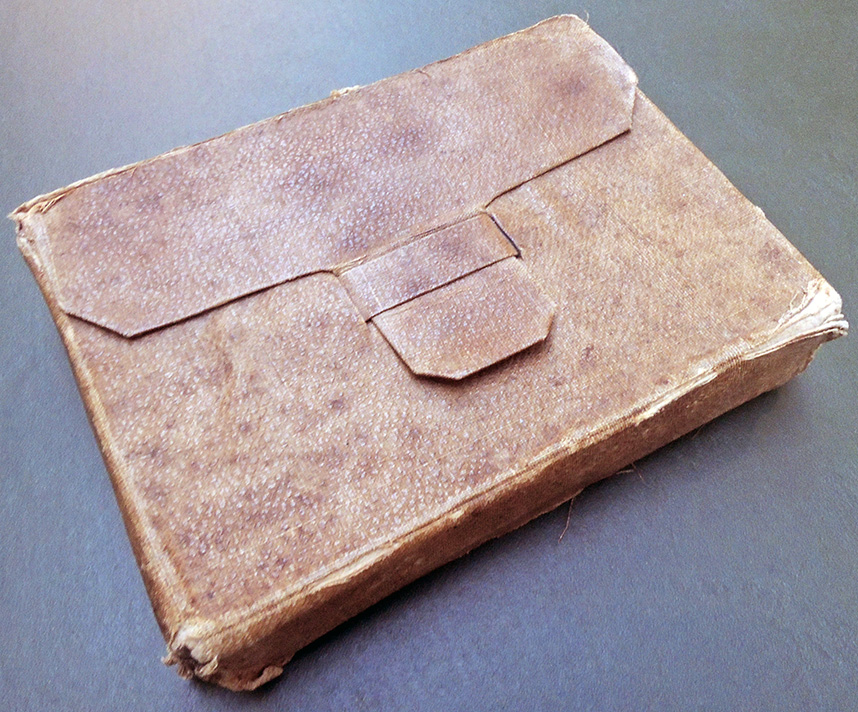

Word rain; or, A discursive introduction to the intimate philosophical investigations of G,r,e,t,a, G,a,r,b,o, it says. New York, Grossman Publishers, 1969. Firestone Library » PS3557.I5 W6 1969; Rare Books Off-Site Storage » RECAP-94763388

For example (a critique of never) = Par esempio (una critica del mai): a melodrama / by Madeline Gins and Arakawa (from The mechanism of meaning). [Place of publication not identified]: A. Castelli, [1974?]. Rare Books Off-Site Storage » RECAP-94765342

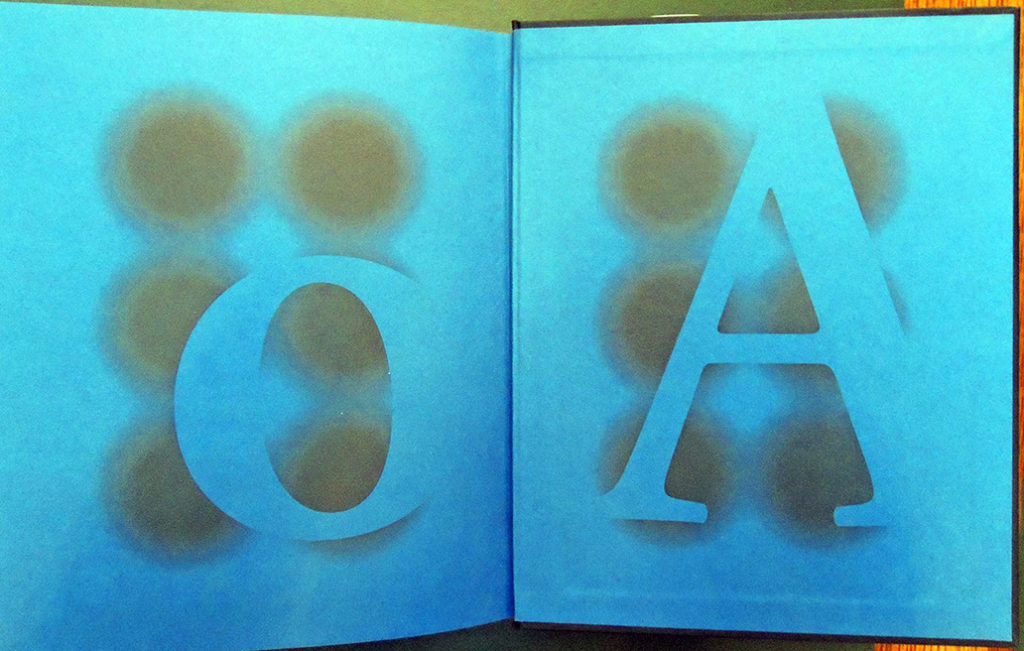

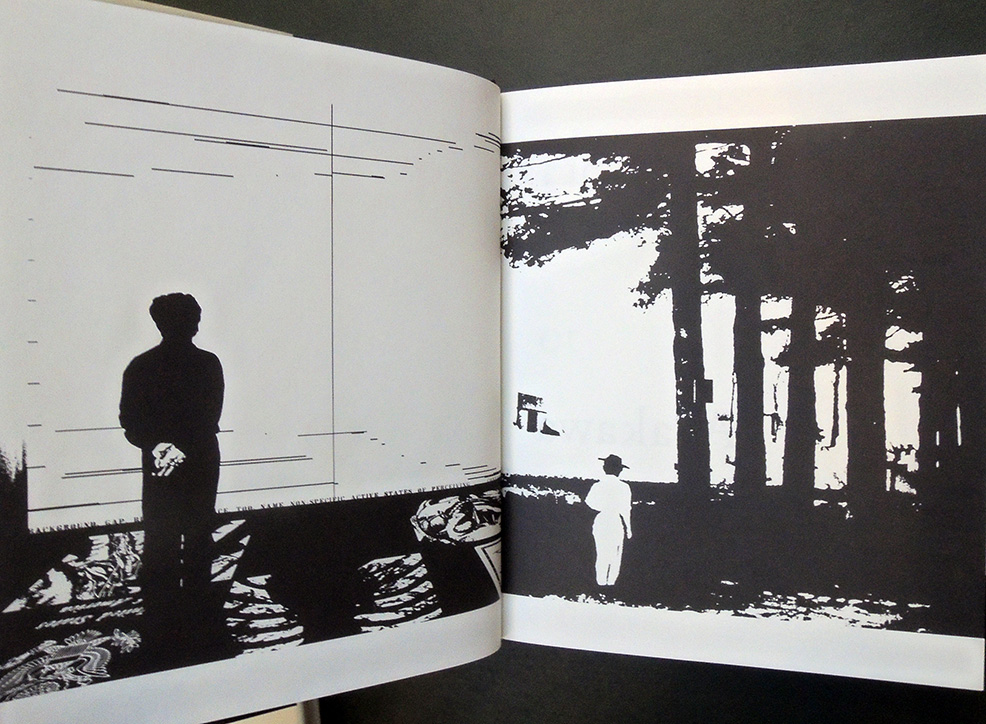

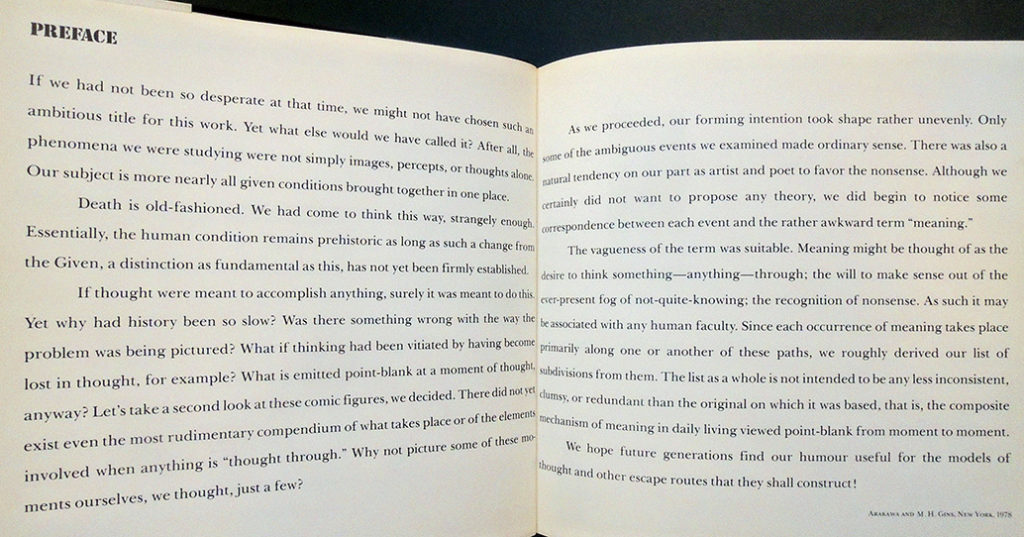

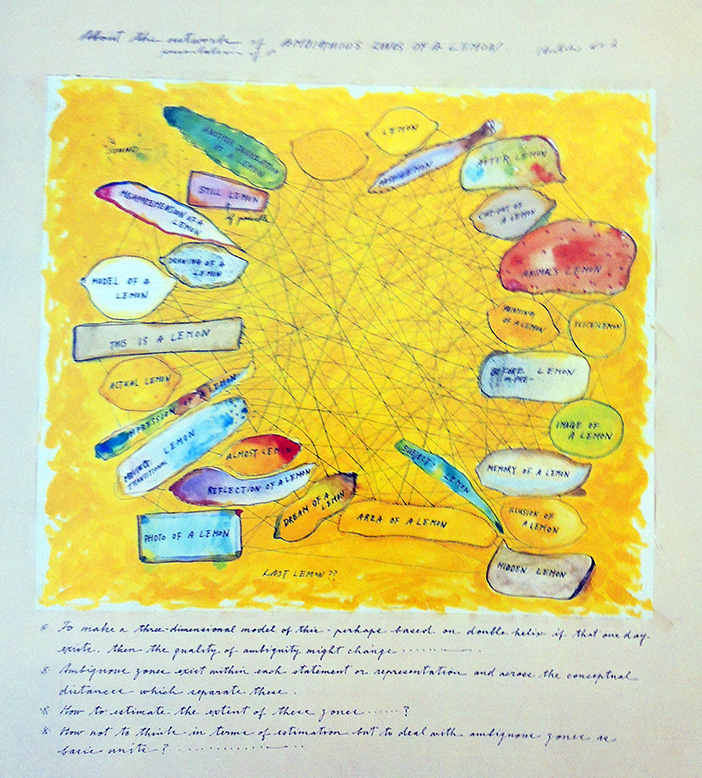

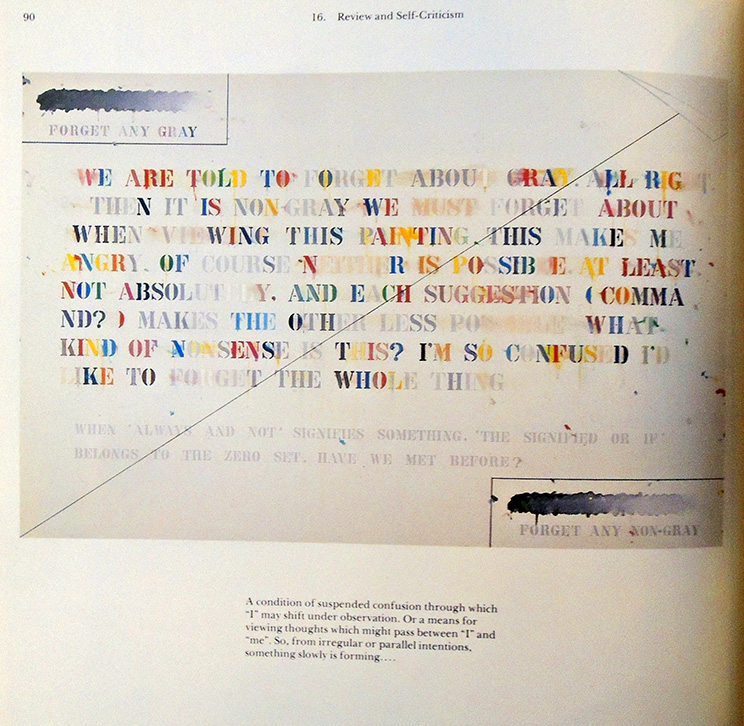

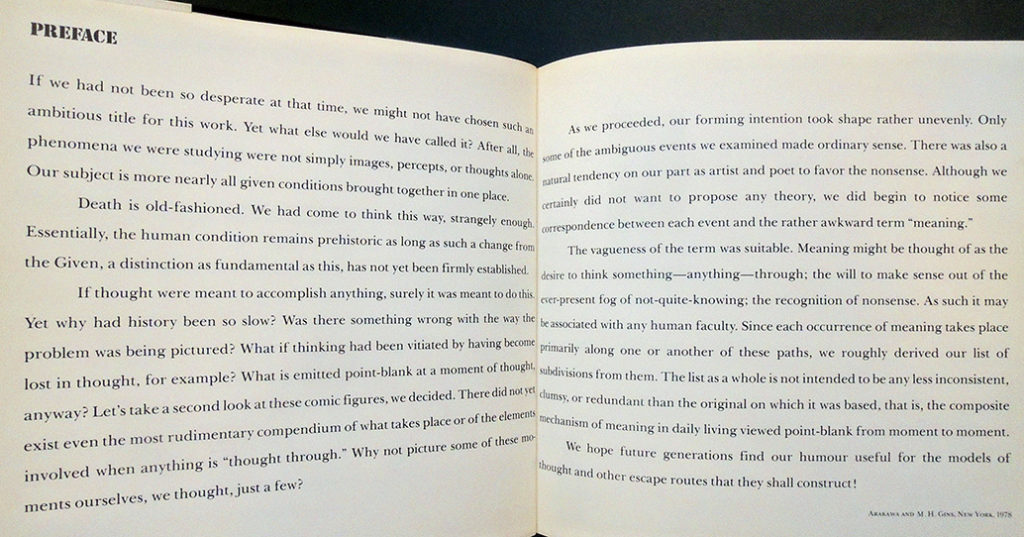

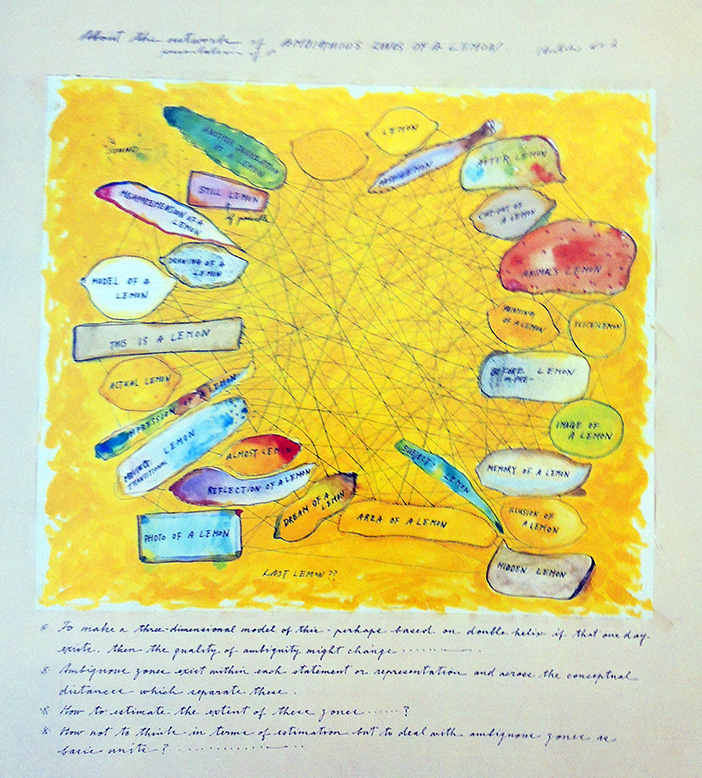

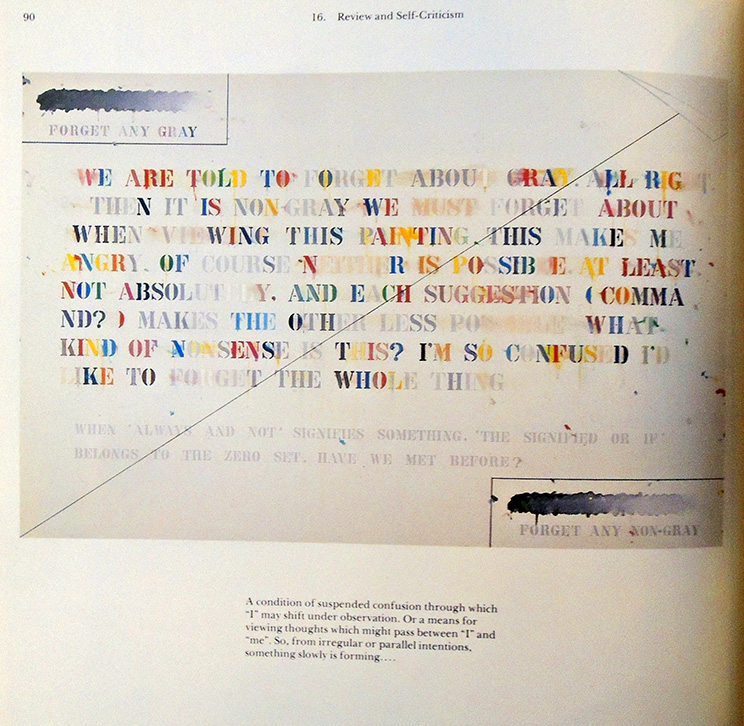

The mechanism of meaning: work in progress (1963-1971, 1978) based on the method of Arakawa / Arakawa and Madeline H. Gins; [editor, Ellen Schwartz]. New York: H. N. Abrams, 1979. N7359.A7 G56; Rare Books Off-Site Storage » RECAP-97151300

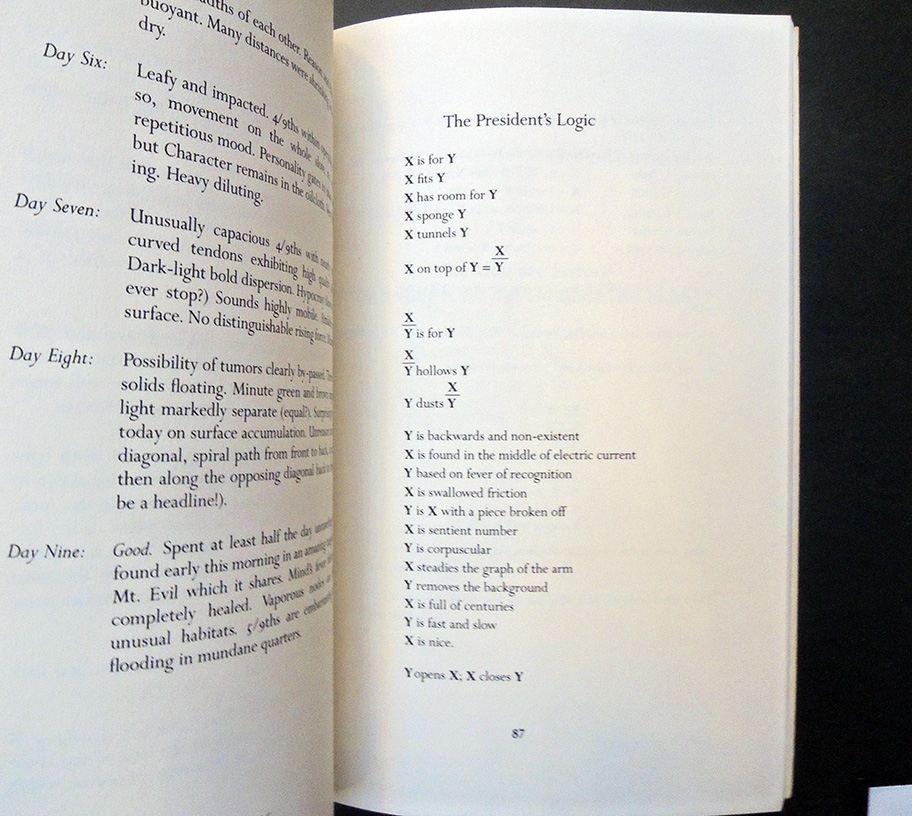

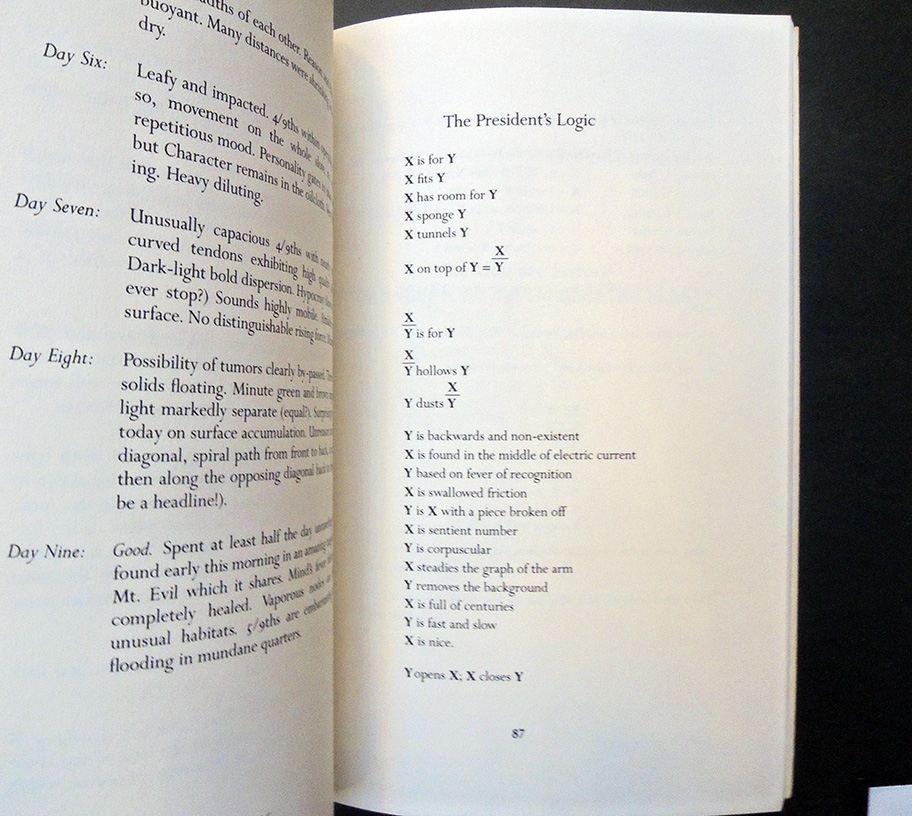

What the president will say and do!! / Madeline Gins. Barrytown, N.Y.: Station Hill, c1984. Rare Books Off-Site Storage » RECAP-33922780

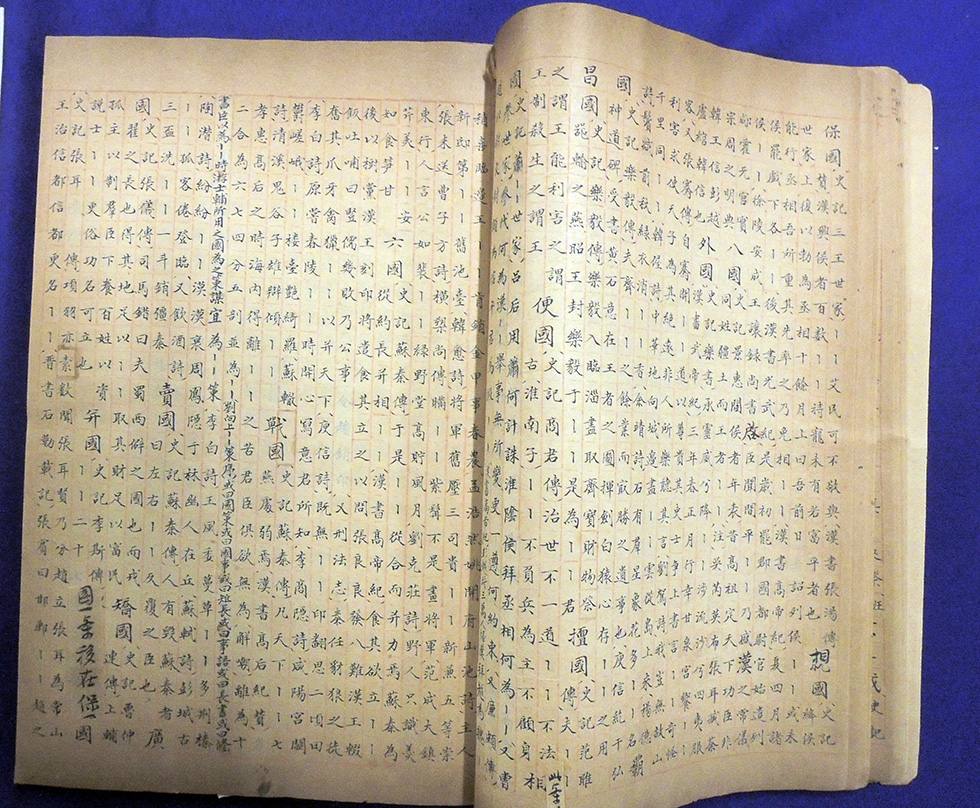

To not to die / Arakawa, Madeline Gins = Shinanai tame ni / Arakawa Shūsaku, Madorin Ginzu; Miura Masashi yaku. Tōkyō: Riburo Pōto, 1988. PS3557.I5 T66 1988

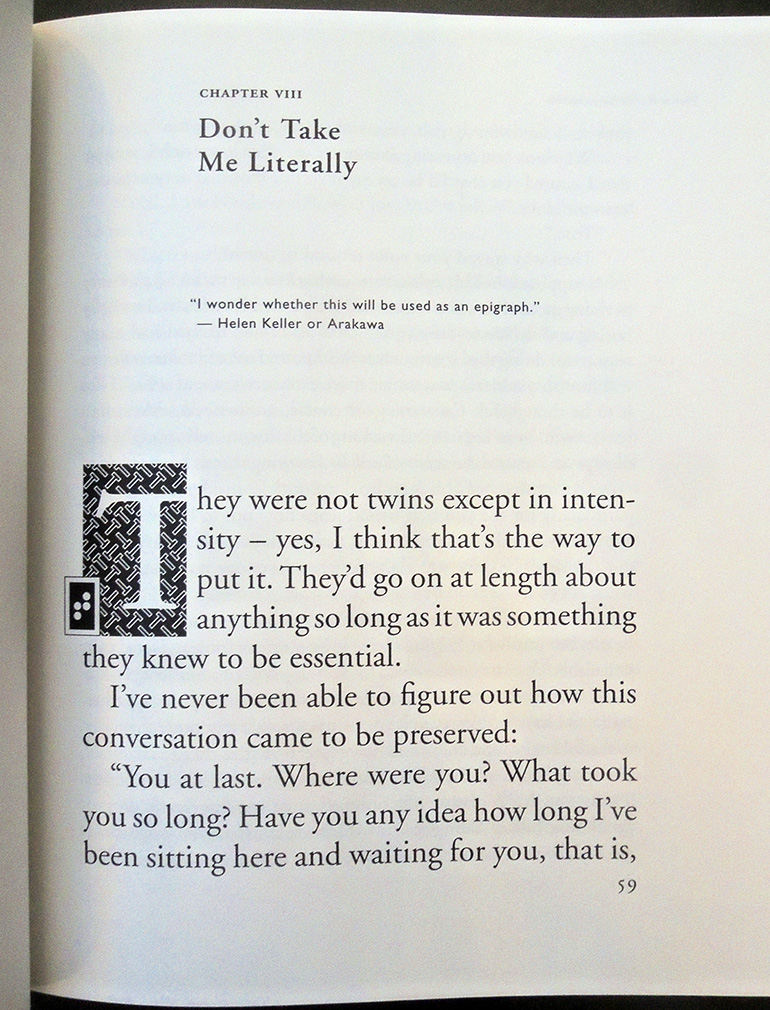

Helen Keller or Arakawa / Madeline Gins. Santa Fe, N.M.: Burning Books; New York: East-West Cultural Studies: D.A.P., distributor, c1994. PS3557.I5 H44 1994; Rare Books Off-Site Storage » RECAP-94763370

Reversible destiny: Arakawa/Gins / [organized by Michael Govan]. New York: Guggenheim Museum: Distributed by H.N. Abrams, c1997. Marquand Library » Oversize N7359.A7 G562 1997q

Architectural body / Madeline Gins and Arakawa. Tuscaloosa, Ala.; London: University of Alabama Press, c2002. Architecture Library » NA2500 .G455 2002. Marquand Library » NA2500 .G455 2002

Making dying illegal: architecture against death: original to the 21st century / Arakawa and Madeline Gins; introduction by Jean-Jacques Lecercle. New York: Roof Books, 2006. HQ1073 .A73 2006g

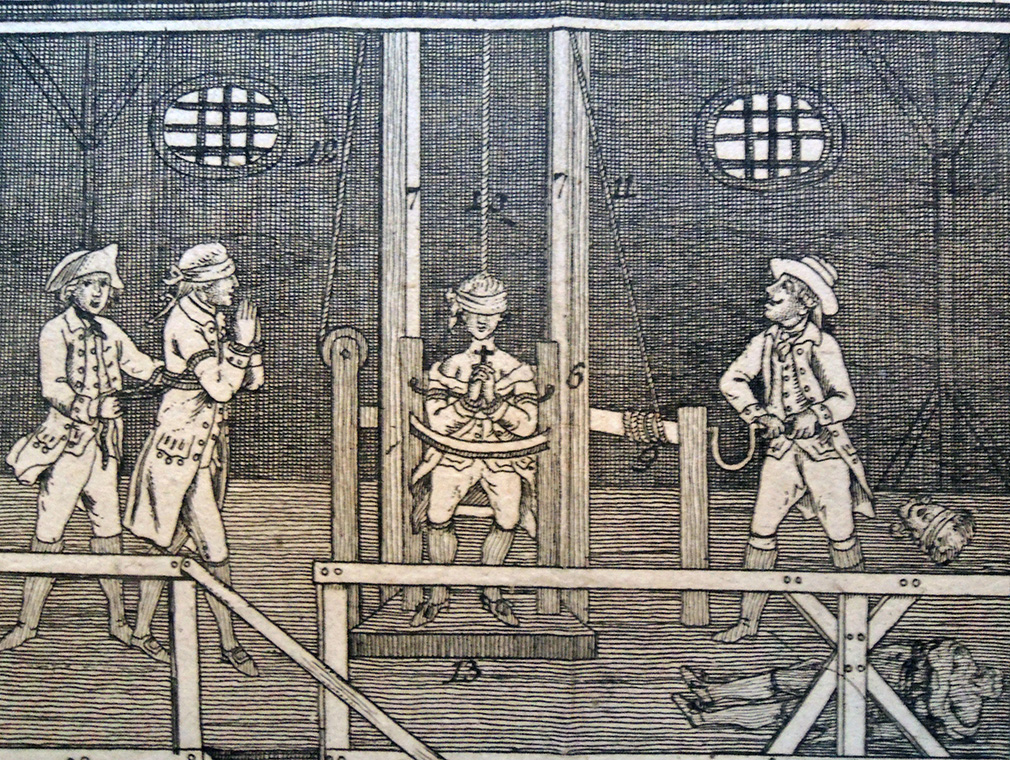

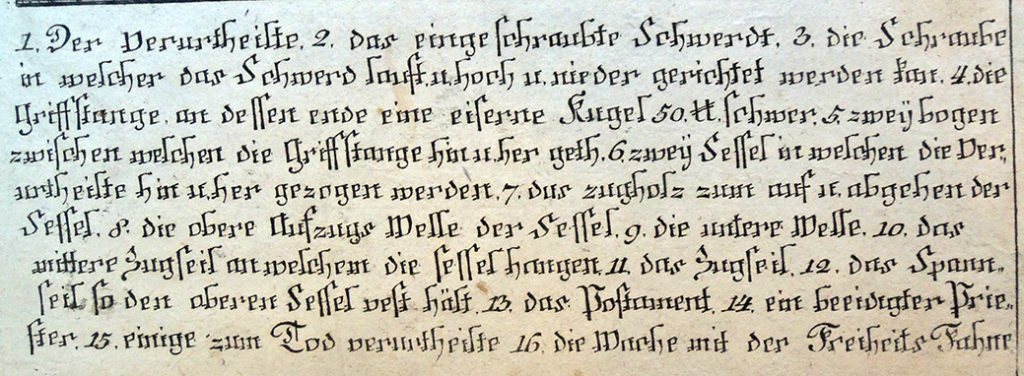

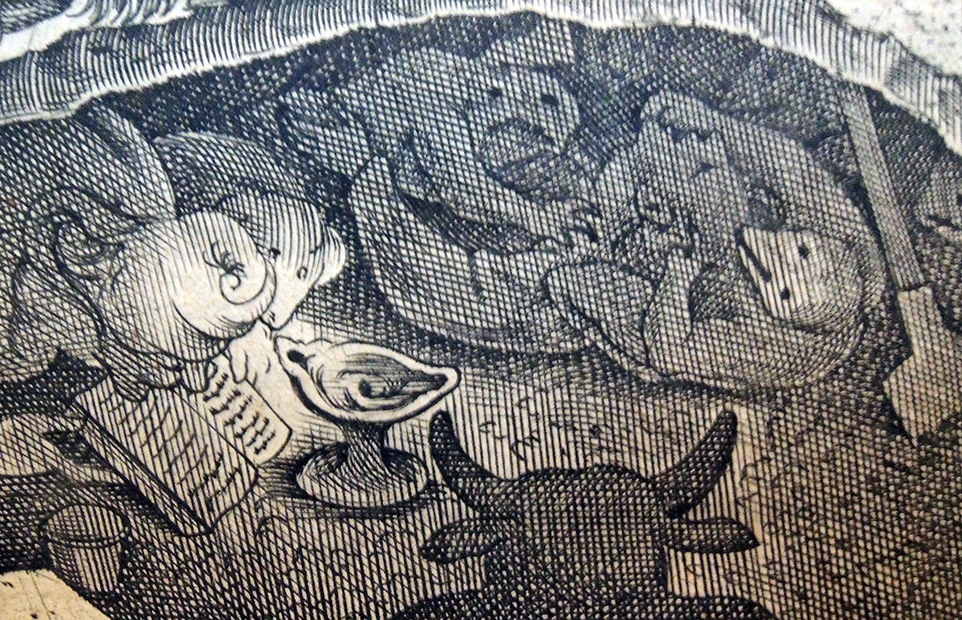

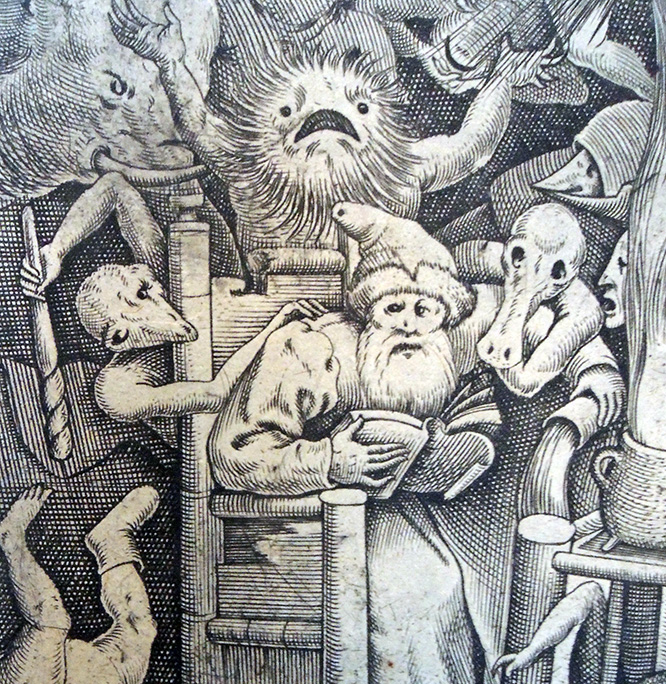

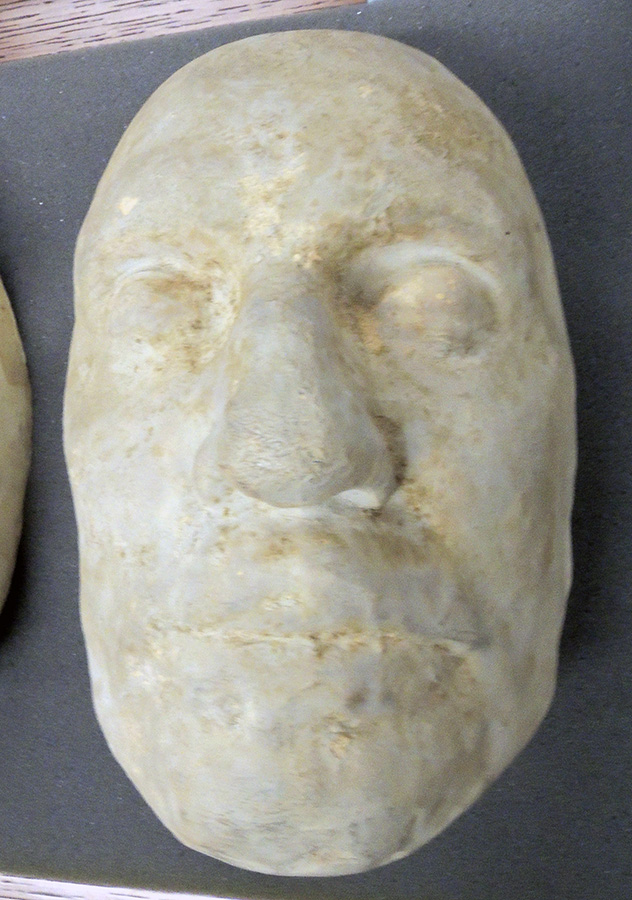

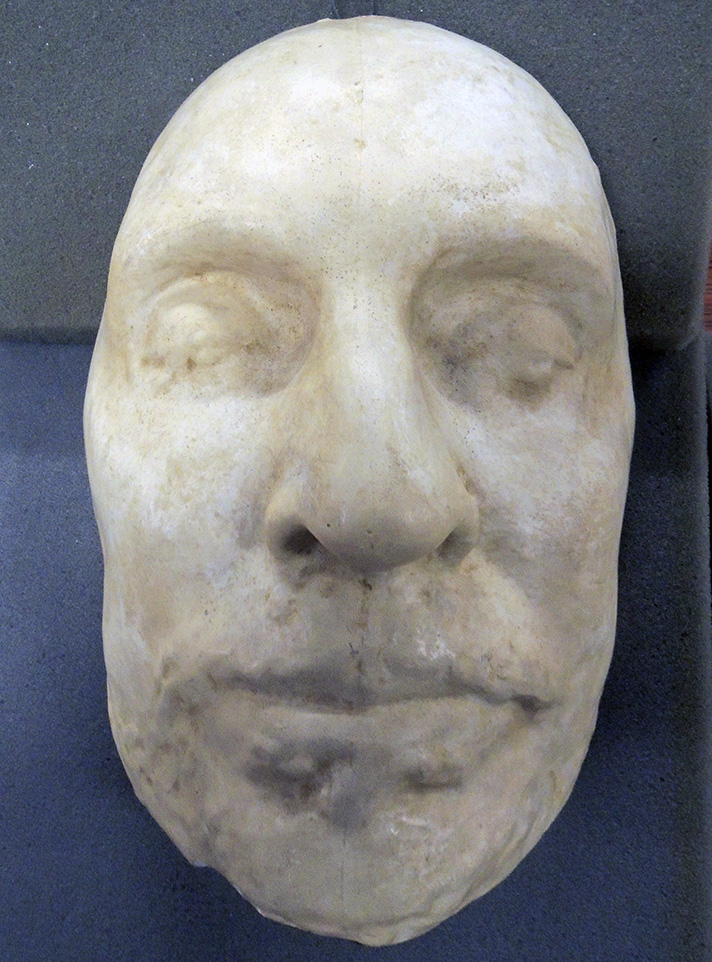

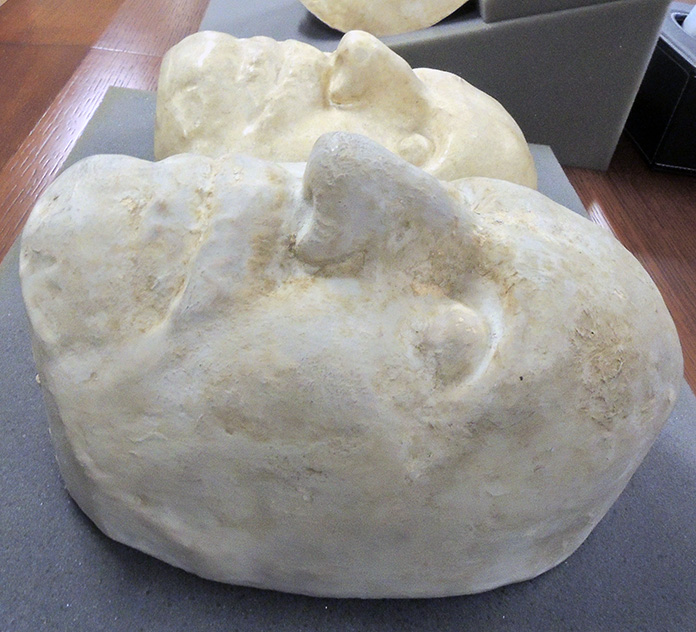

Johann Martin Will (1727 -1806), Vorstellung der Kopf Maschiene in Paris. Vermöge welcher in einer viertelstund 25 Personen könen enthauptet werden [Representation of the Head Machine by which 25 persons can be beheaded every quarter of an hour] [Augsburg: Johann Martin Will], 1792. Etching with engraving, engraved text in German and French. Graphic Arts Collection GAX 2019-in process

Johann Martin Will (1727 -1806), Vorstellung der Kopf Maschiene in Paris. Vermöge welcher in einer viertelstund 25 Personen könen enthauptet werden [Representation of the Head Machine by which 25 persons can be beheaded every quarter of an hour] [Augsburg: Johann Martin Will], 1792. Etching with engraving, engraved text in German and French. Graphic Arts Collection GAX 2019-in process