(grainy image due to low light during hanging)

(grainy image due to low light during hanging)

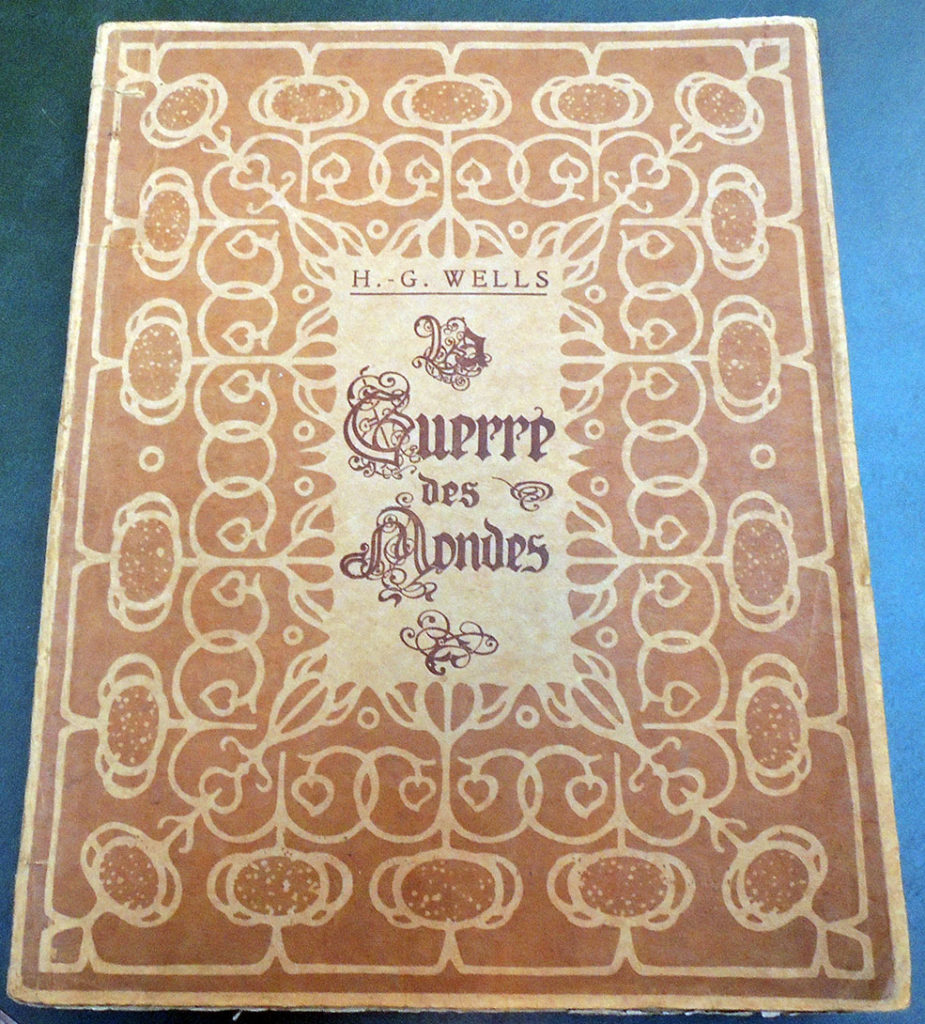

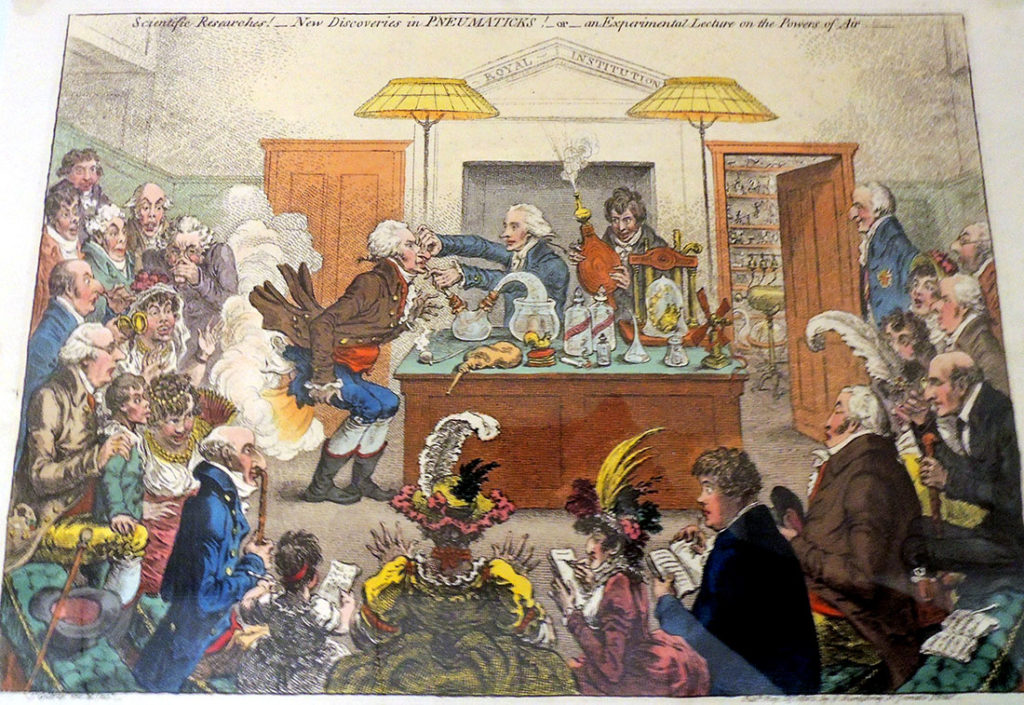

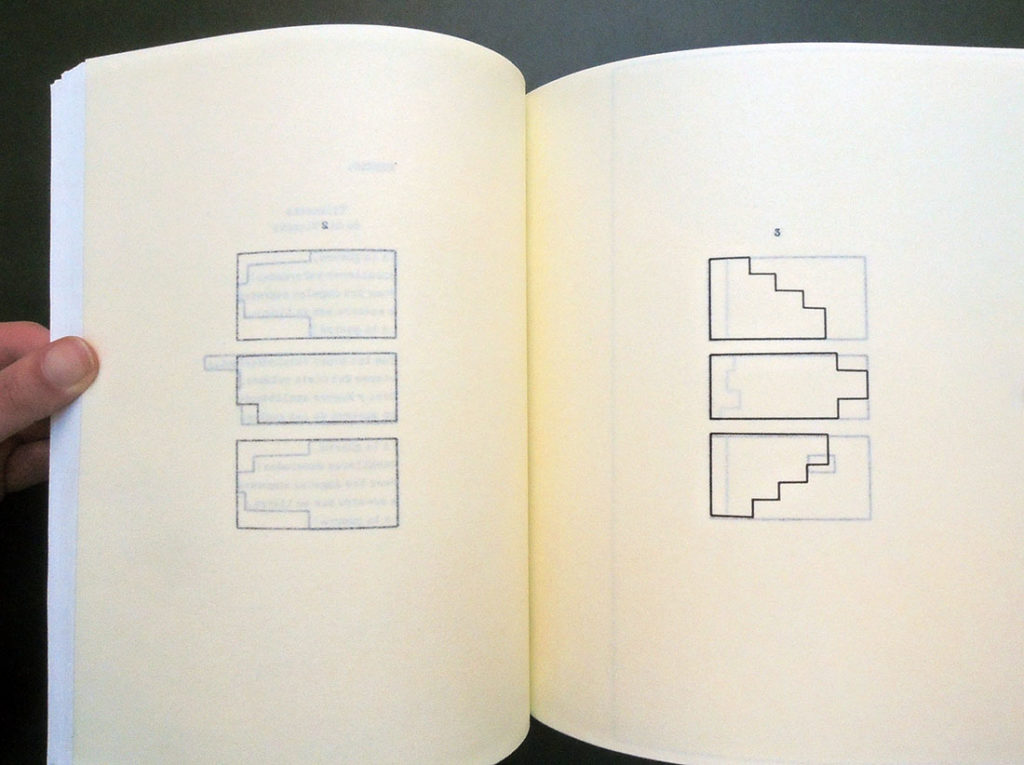

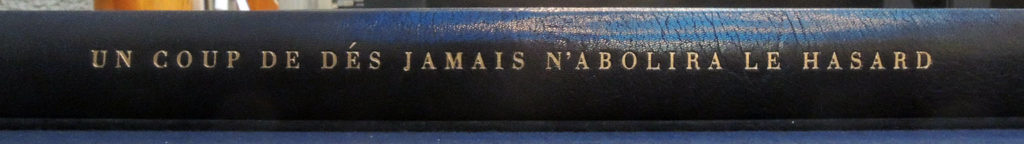

It is a great privilege to have work from the Graphic Arts Collection included in an exhibition at the Musée Rodin in Paris. Opening November 6, 2018, and running through February 24, 2019, the show entitled Rodin, Dessiner, Découper, includes nearly 250 drawings by Auguste Rodin (1840-1917), of which 90 are his rare and often surprising cut and assembled figures, 6 loaned by Princeton University’s Graphic Arts Collection. “Jouant de la mise en espace de ces corps,” writes curator Sophie Biass-Fabiani, “ce procédé révèle des silhouettes découpées audacieuses et un dynamisme d’une grande modernité. Cette exposition annonce un des modes d’expression novateurs du XXe siècle.”

http://musee-rodin.fr/fr/exposition/rodin-dessiner-decouper

The museum’s site goes on to quote Rodin, who said,

The museum’s site goes on to quote Rodin, who said,

“‘I have a great weakness for these little sheets of paper.’ This is how Rodin showed his attachment to his drawn work. From his beginnings, Rodin realized–independently of his sculptures–drawings that he executed according to the living model. He presents his drawings in all exhibitions devoted to him, first in Brussels, Amsterdam, Rotterdam, The Hague in 1899, then Paris in 1900, Prague in 1902 or Düsseldorf in 1904. The museum retains most of this drawn work, about 7500 leaves.

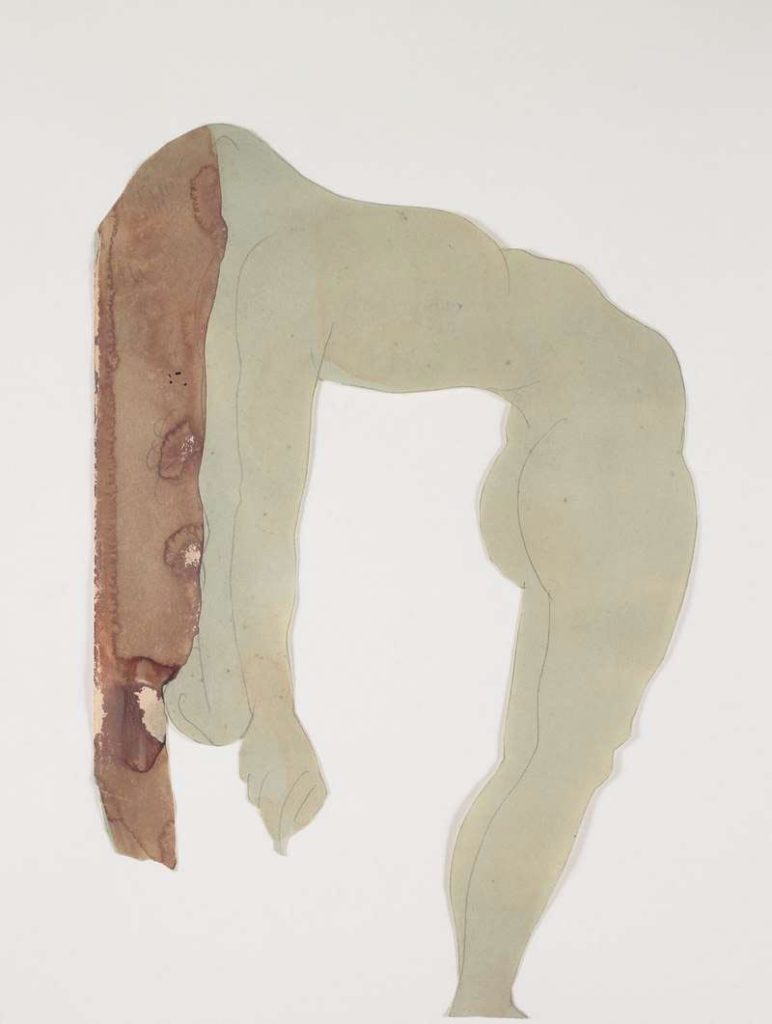

An unprecedented mode of operation: drawing, cutting. Rodin submits his drawings made from a first throw to various metamorphoses. He decodes his drawings, identifies the line that suits him, sets the color using watercolor, cuts out his figures, puts them back, assembles them to other figures and gradually builds an unexpected device. In his early years, Rodin cut drawings and sketches that he pasted into albums. Between 1900 and 1910, he cut a hundred drawings of watercolor nudes which are the heart of this exhibition. By cutting them out, Rodin likes to manipulate them, to situate them in space in multiple ways, to cut them off voluntarily.”

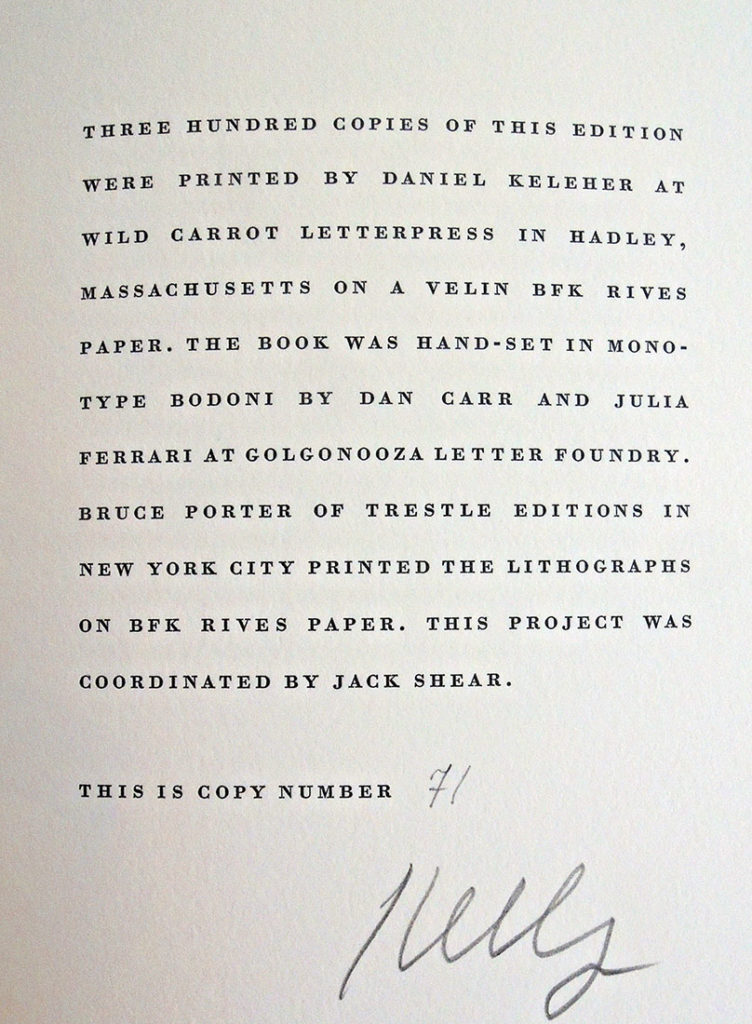

More information on how Rodin’s work made it to Princeton can be found here: https://graphicarts.princeton.edu/2018/03/10/auguste-rodin-cutouts/. Hanging and lighting will be completed this week and their beautiful exhibition catalogue with full color images will be available at Princeton next Monday.

“He plays with the small figures of paper which are the equivalent of his plaster figures. By relating these carvings to the three-dimensional character of the sculpture, the carved figures appear as a new “object” between the two-dimensional design and the sculpture. In another series, Rodin executes from his cut-out figures real assemblages that he fixes himself on a new support, interweaving the bodies in a new composition. Drawn and cut, these drawings are not mere technical accessories: they have conquered their status as full-fledged works. The dynamism of the silhouettes announces the modernity of Matisse.” –Sophie Biass-Fabiani, curator

http://www.musee-rodin.fr/fr/visiter/informations-pratiques-paris