John Taylor Arms, Loop the Loop, 1920. Original aquatint printed directly from the copper plate, frontispiece, The Print Connoisseur December 1920.

John Taylor Arms, Loop the Loop, 1920. Original aquatint printed directly from the copper plate, frontispiece, The Print Connoisseur December 1920.

Frederick Reynolds, Castle of Vitre, 1920. Original mezzotint printed directly from copper plate, frontispiece The Print Connoisseur, October 1920

Frederick Reynolds, Castle of Vitre, 1920. Original mezzotint printed directly from copper plate, frontispiece The Print Connoisseur, October 1920

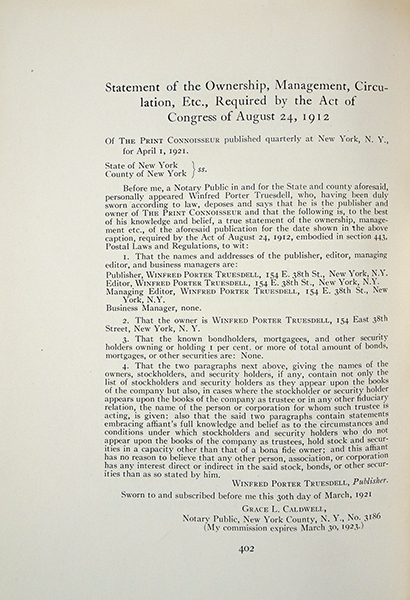

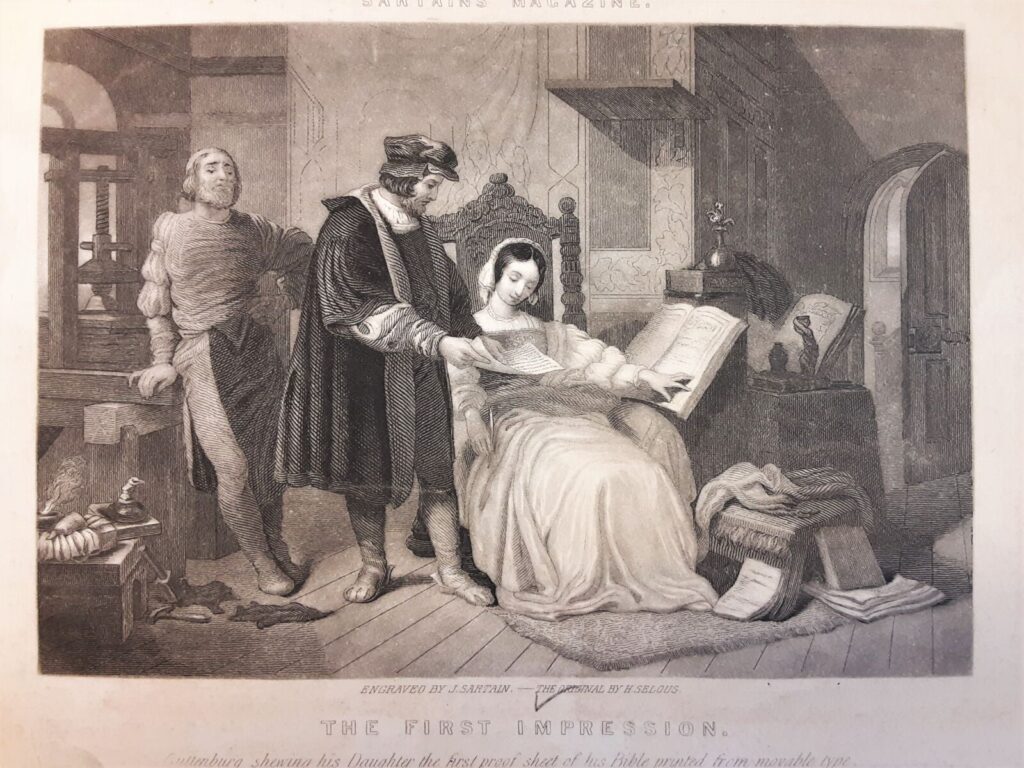

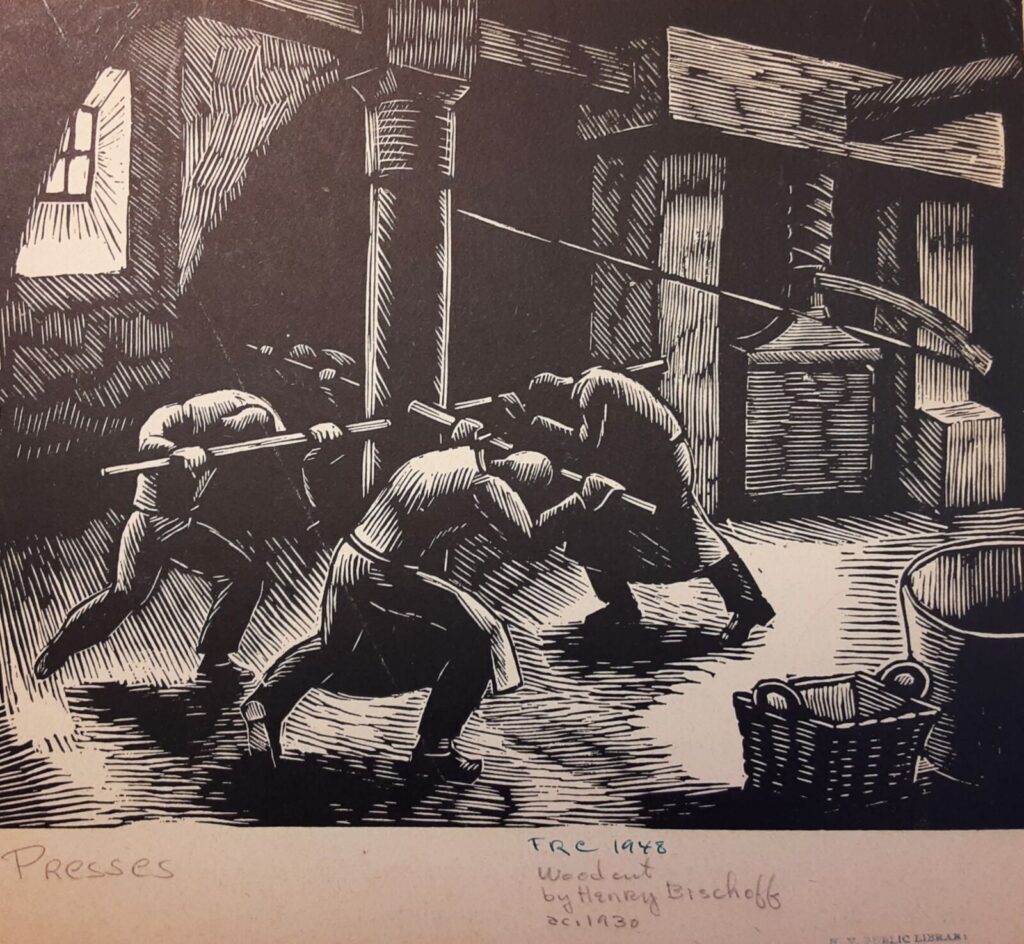

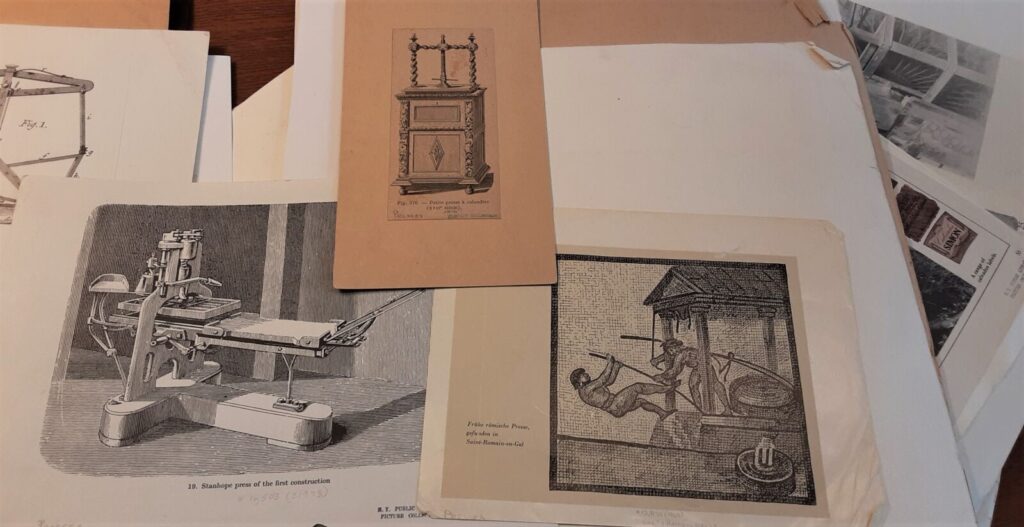

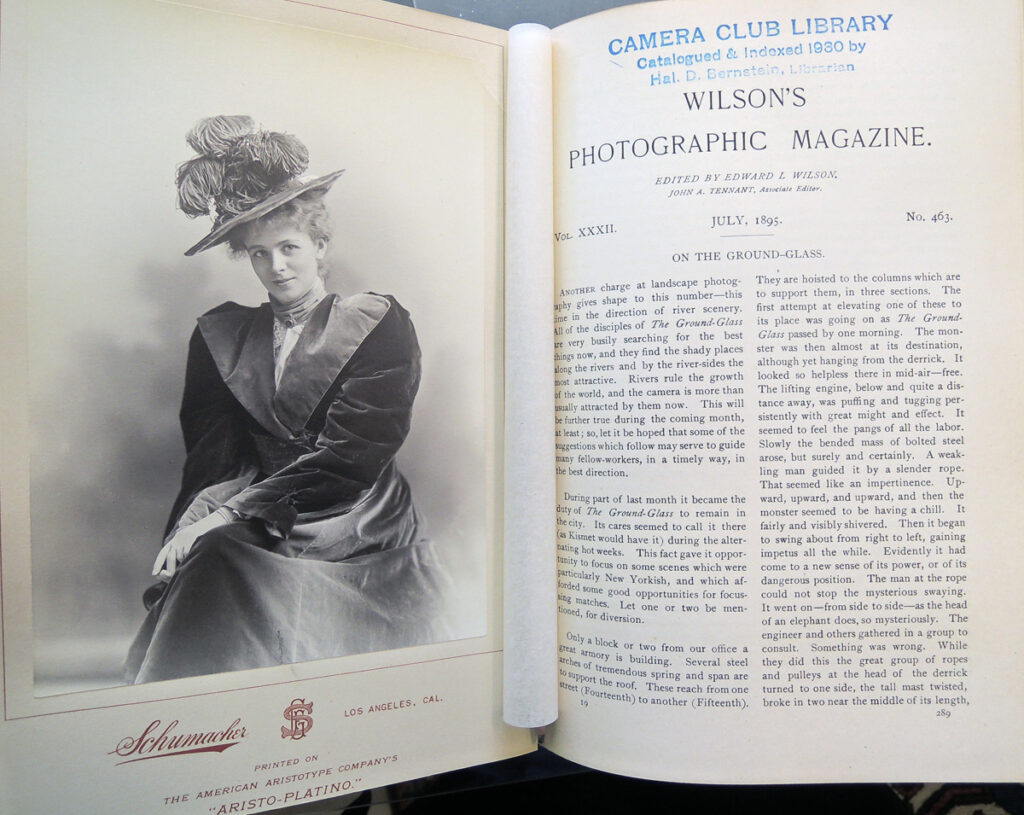

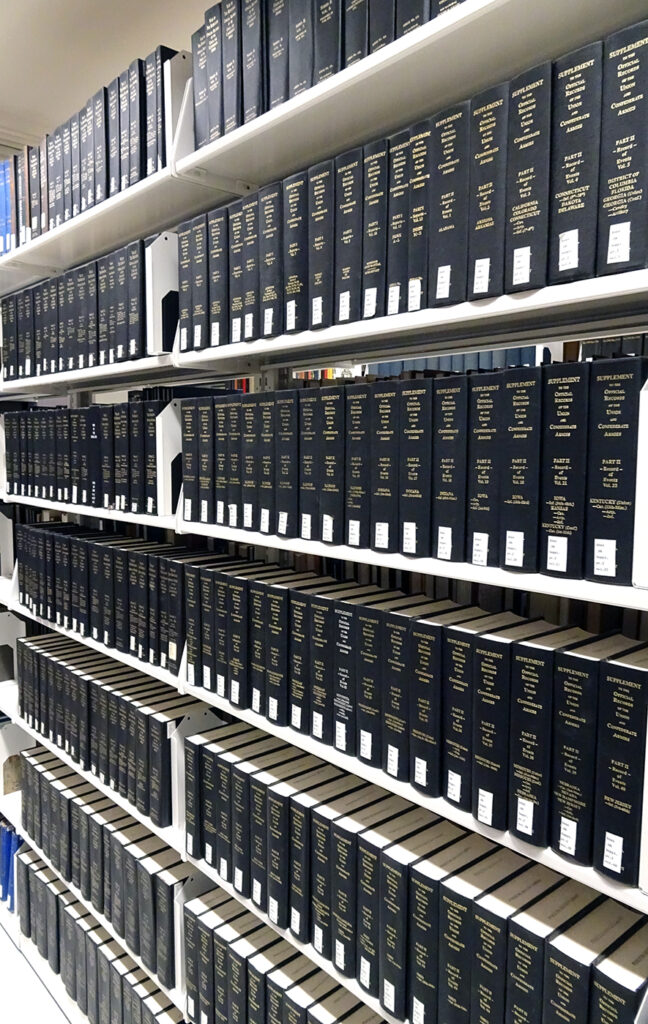

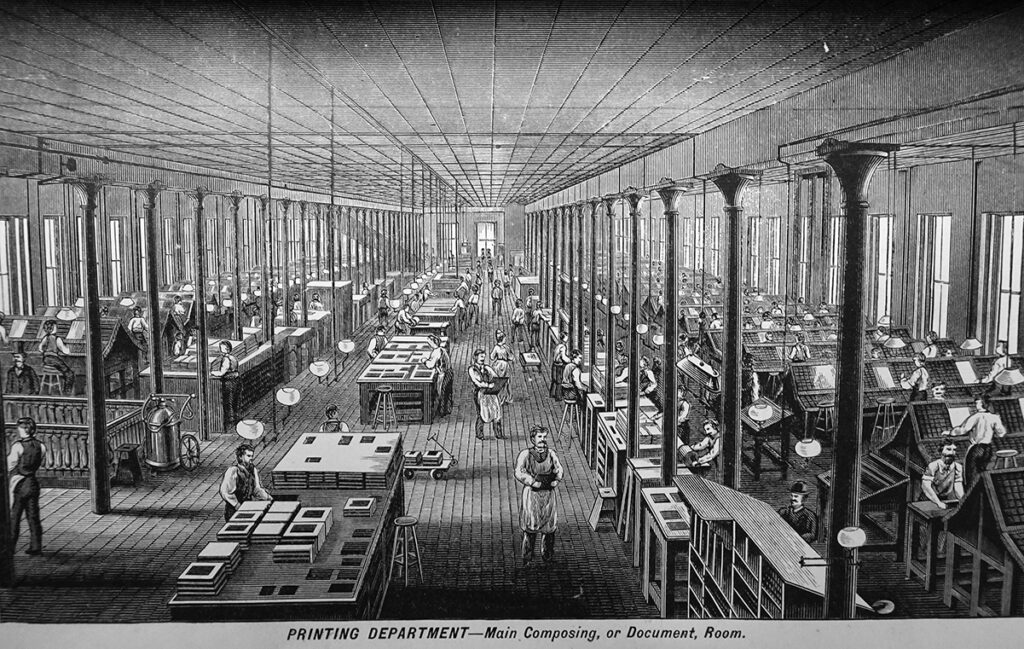

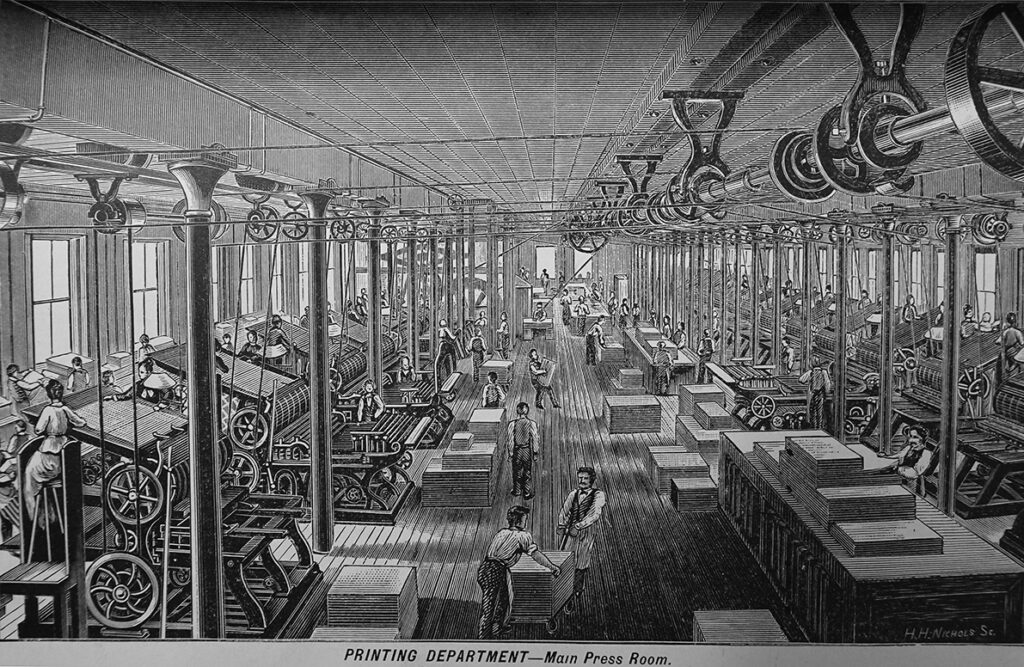

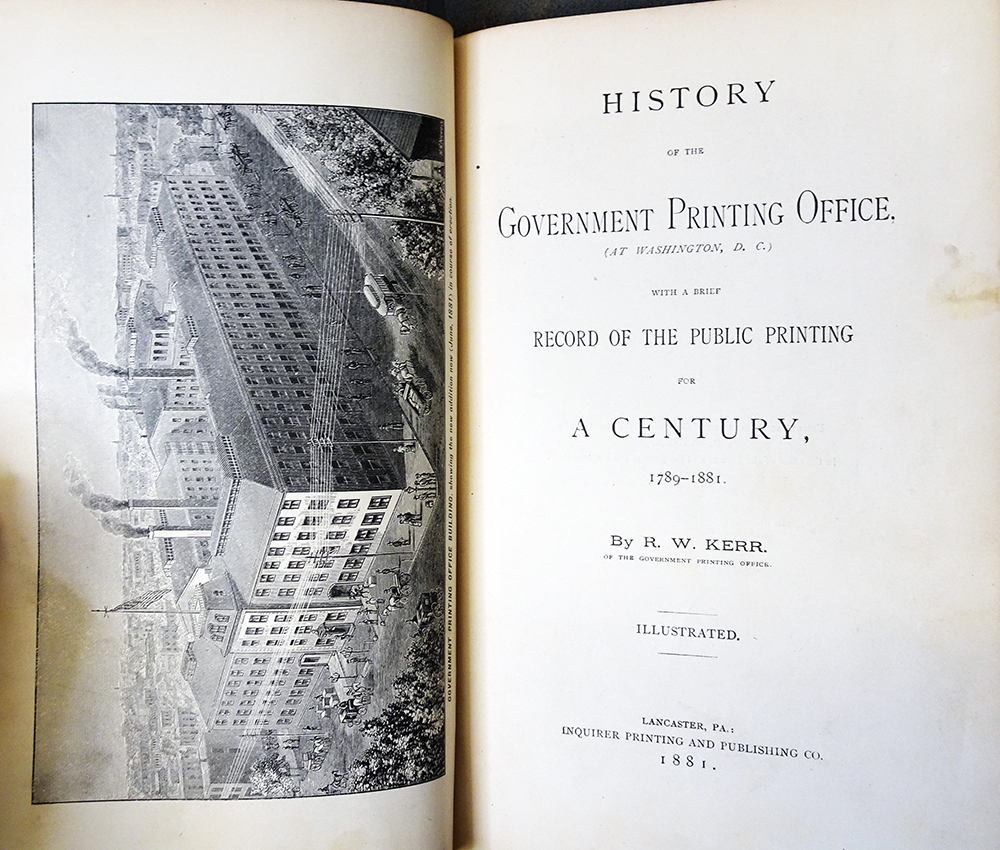

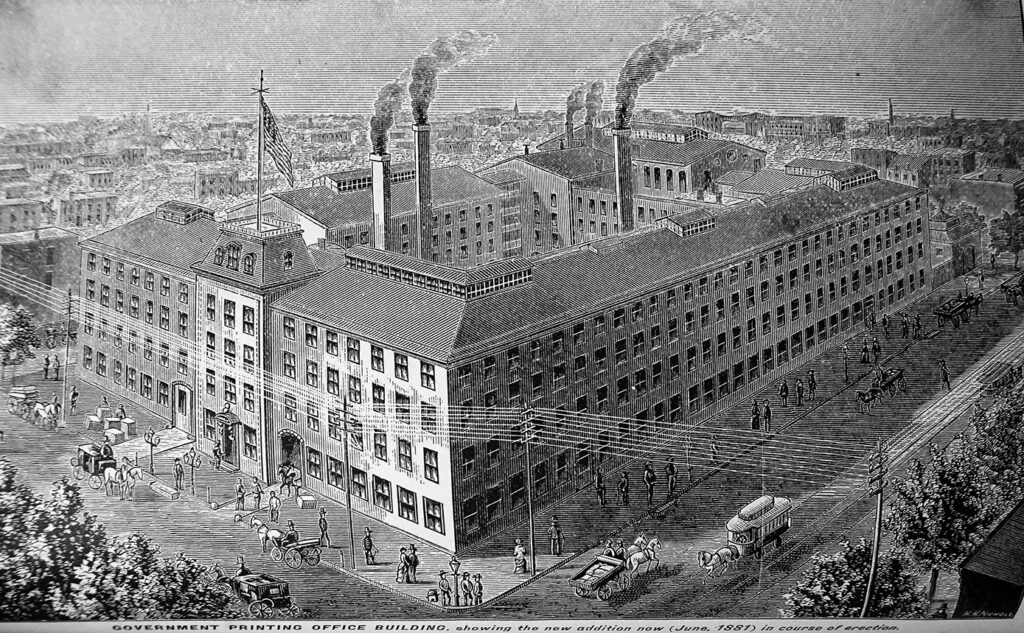

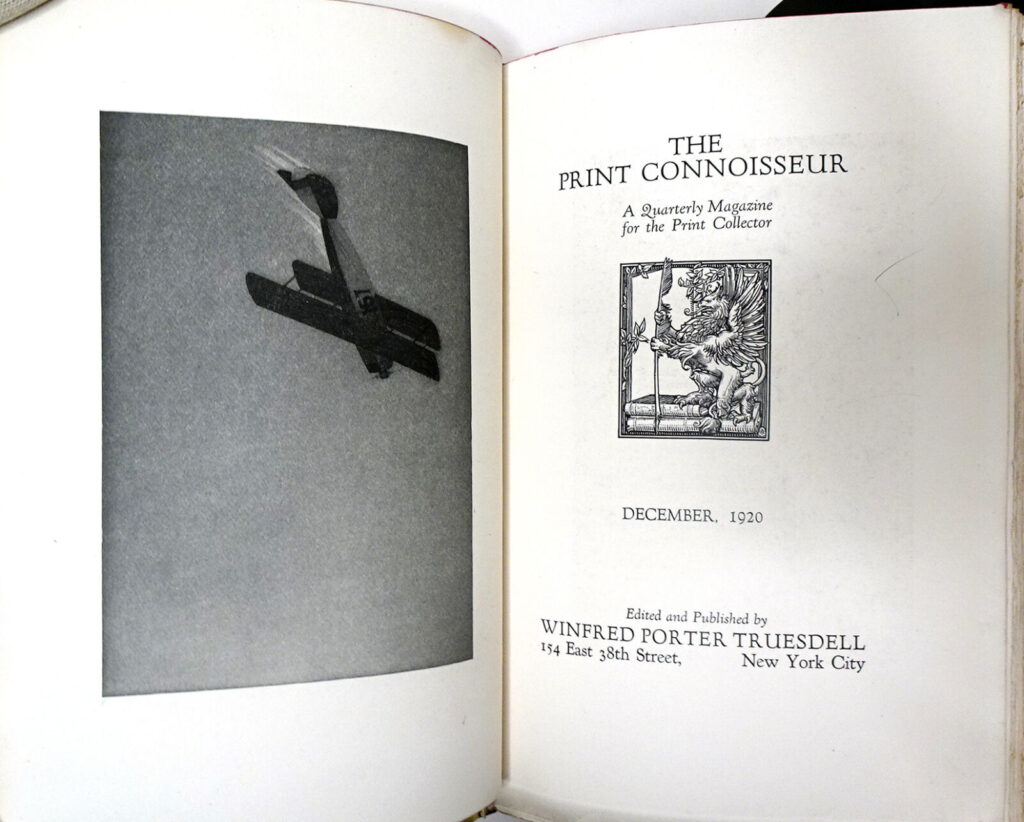

While clearing an office recently, several early volumes of The Print Connoisseur appeared. Published by Winfred Porter Truesdell (1877-1939) from 1920 to 1932, the quarterly magazine was distinguished by its frontispiece prints, printed directly from the original copper plates and bound into each issue. Truesdell did the printing for the first year himself from his New York studio, but the second and third year were printed at the Clinton Press in Plattsburgh, NY. During this time, Truesdell moved to Champlain, NY, where he joined Hugh McLellan’s Moorsfield Press, and from 1924 forward he and McLellan did the printing.

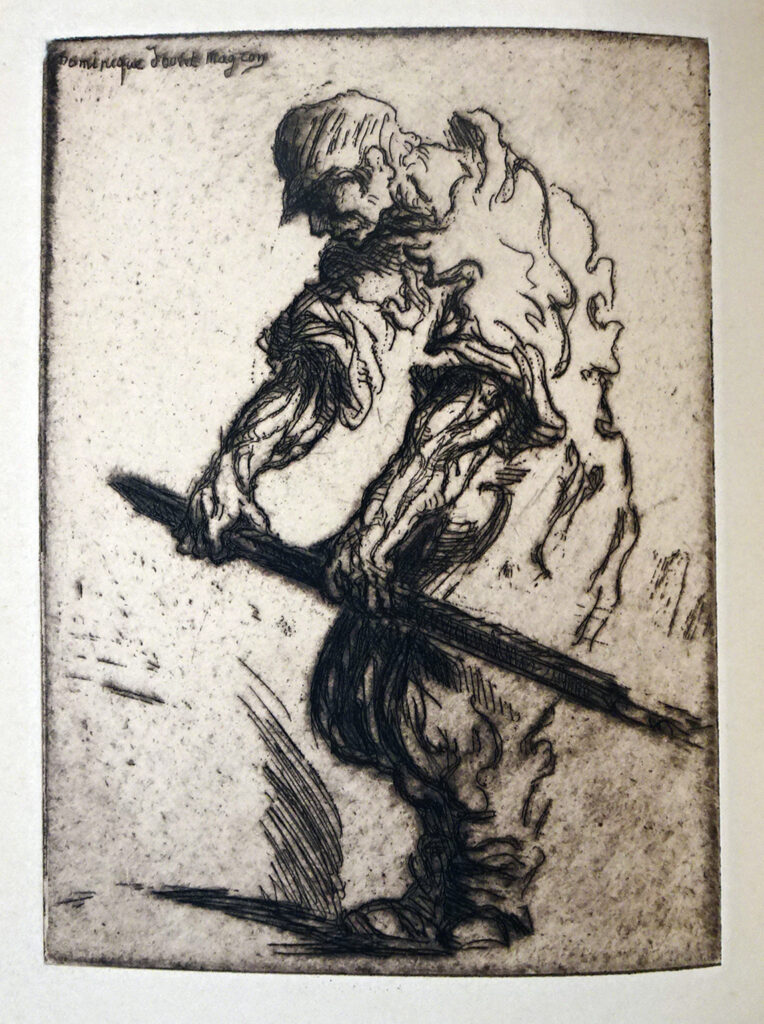

Dominique Jouvet-Magron, Le Manoeuvre au Levier, 1923. Original etching printed directly form the copper plate, frontispiece The Print Connoisseur April 1923.

Dominique Jouvet-Magron, Le Manoeuvre au Levier, 1923. Original etching printed directly form the copper plate, frontispiece The Print Connoisseur April 1923.

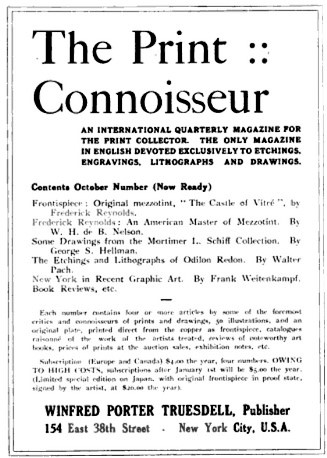

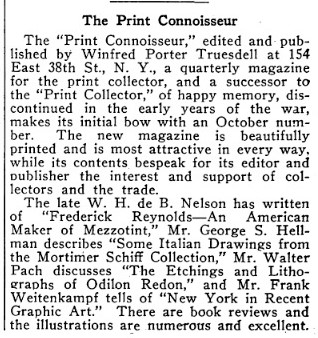

“The Print Connoisseur,” American Art News 19, no. 4 (November 6, 1920), p. 4. Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/25589698

“The Print Connoisseur,” American Art News 19, no. 4 (November 6, 1920), p. 4. Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/25589698

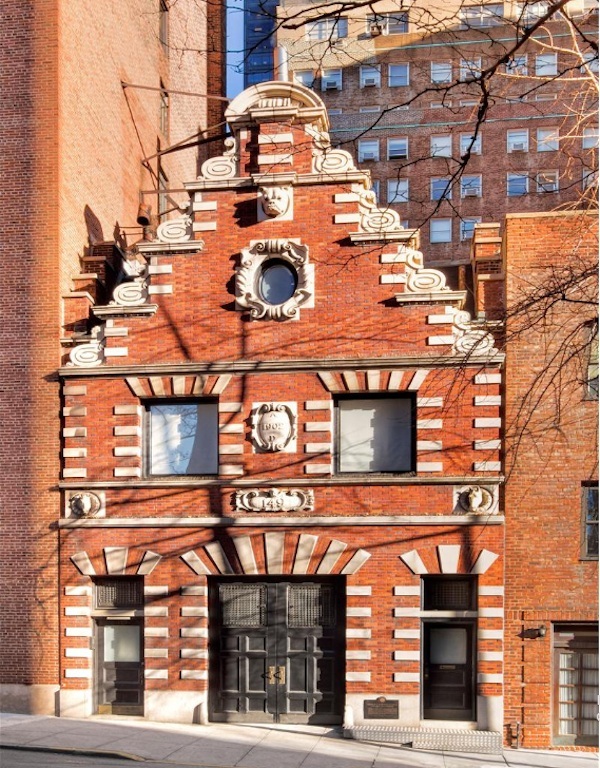

Truesdell’s New York City studio was located in the fashionable east side, not far from J.P. Morgan’s home and library. The studio at 154 East 38th Street was shared with British print maker Frederick Thomas Reynolds (1882-1945) and also served as the meeting place for the Brooklyn Society of Etchers.

Today the address leads to an empty lot, but a sense of the neighborhood can be had thanks to the building directly across the street, owned in the 1920s by Edith Bowdoin, daughter of financier George S. Bowdoin. Although Bowdoin had her father’s carriage house converted to accommodate her automobiles, the façade remained untouched. In the 21st century, the building housed the Gabarron Foundation’s Carriage House Center for the Arts, which hosted exhibitions and lectures until 2011.

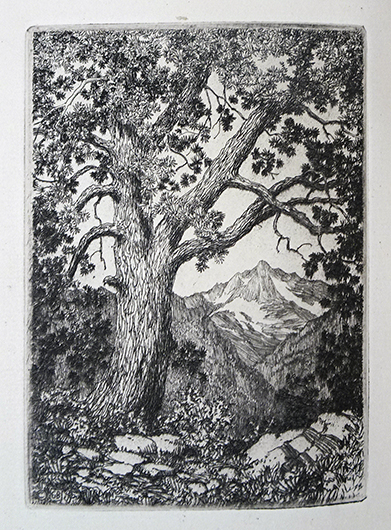

George Elmer Burr, Moraine Park, Colo., 1921. Original etching printed directly from copper plate, frontispiece The Print Connoisseur June 1921.

George Elmer Burr, Moraine Park, Colo., 1921. Original etching printed directly from copper plate, frontispiece The Print Connoisseur June 1921.

The Print Connoisseur is available digitally through Hathi Trust and has been indexed by David Patrick at: http://www.moorsfieldpress.com/truesdell/the_print_connoisseur_by_winfred_porter_truesdell.html

The Print Connoisseur is available digitally through Hathi Trust and has been indexed by David Patrick at: http://www.moorsfieldpress.com/truesdell/the_print_connoisseur_by_winfred_porter_truesdell.html

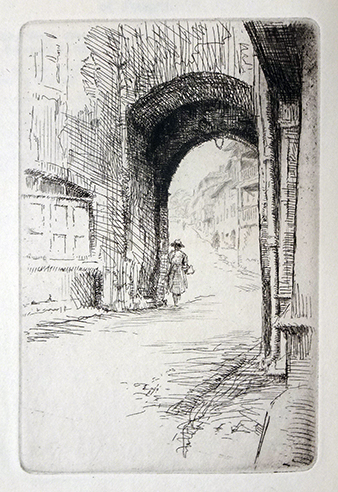

Maurice Victor Achener (1881-1963), Annecy, Porte Perriere, 1923. Original etching printed directly from the copper plate, frontispiece The Print Connoisseur October 1923.

Maurice Victor Achener (1881-1963), Annecy, Porte Perriere, 1923. Original etching printed directly from the copper plate, frontispiece The Print Connoisseur October 1923.

George C. Wales, Outbound, 1923. Original etching printed directly from the copper, frontispiece The Print Connoisseur January 1923.

George C. Wales, Outbound, 1923. Original etching printed directly from the copper, frontispiece The Print Connoisseur January 1923.