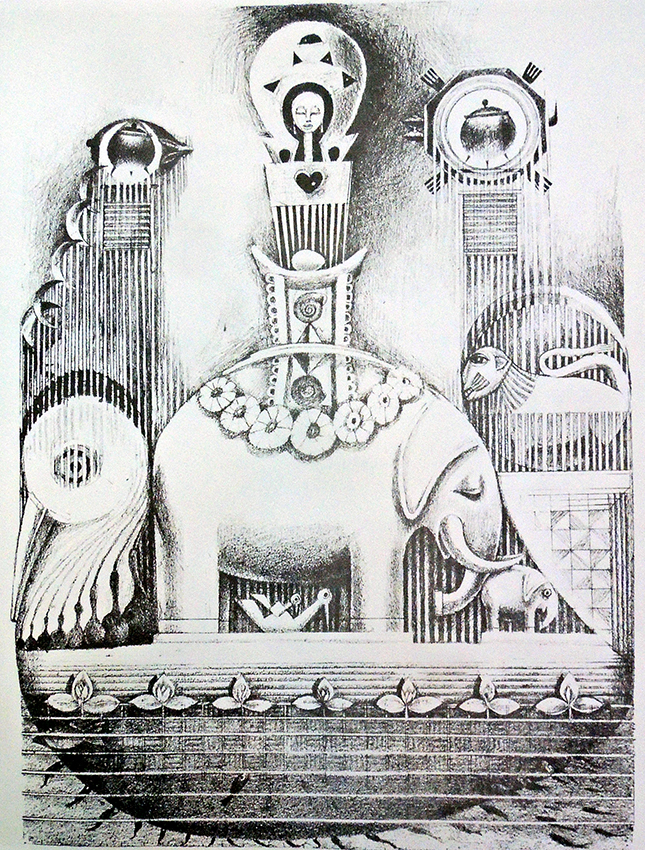

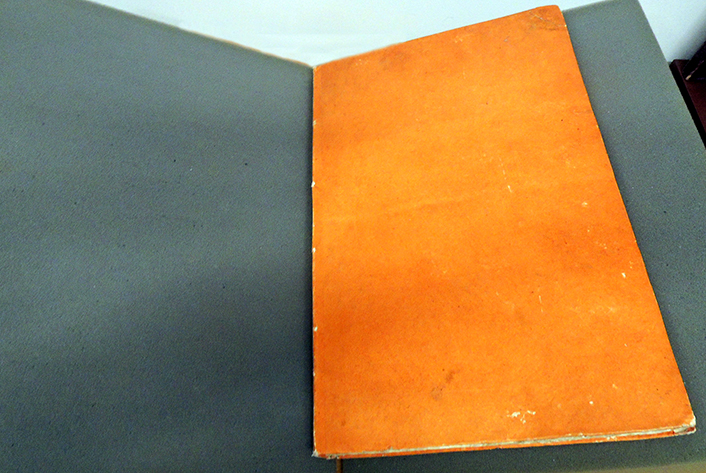

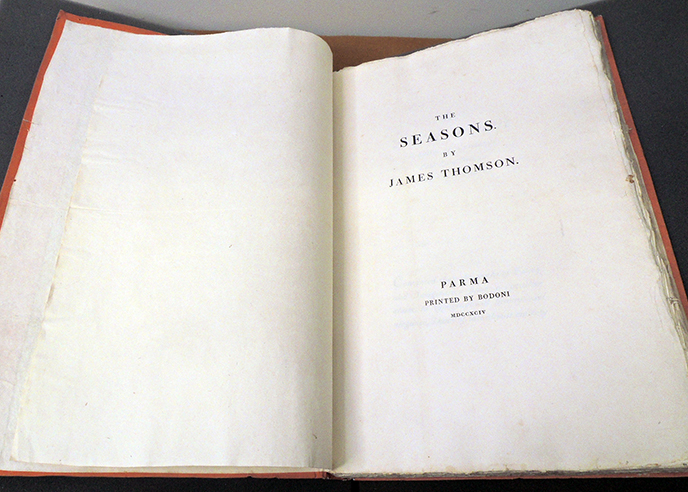

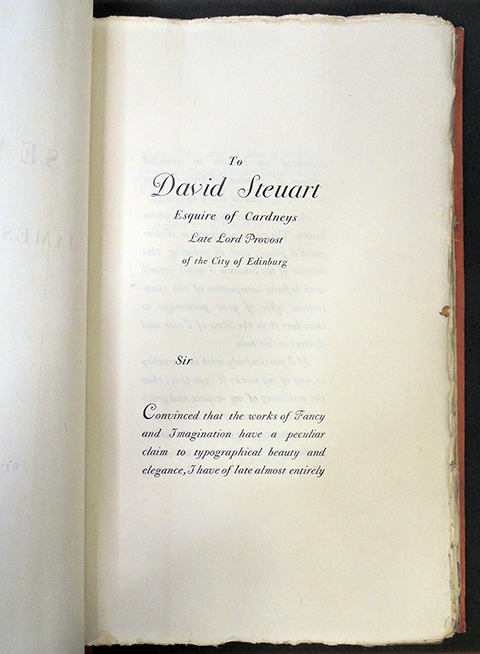

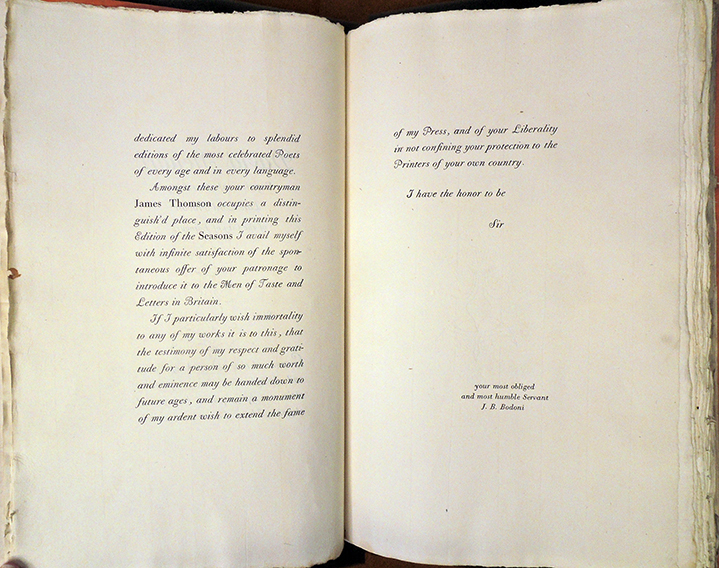

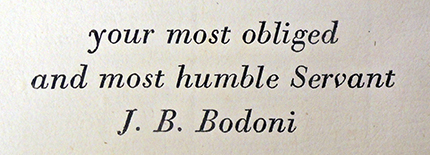

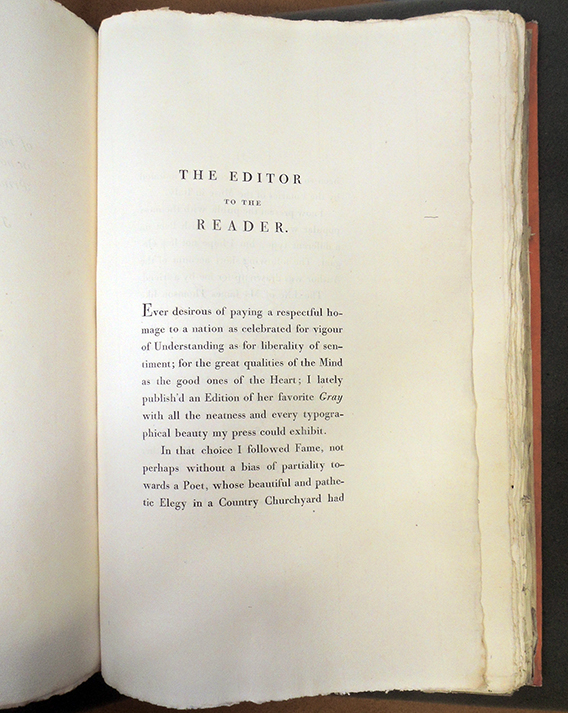

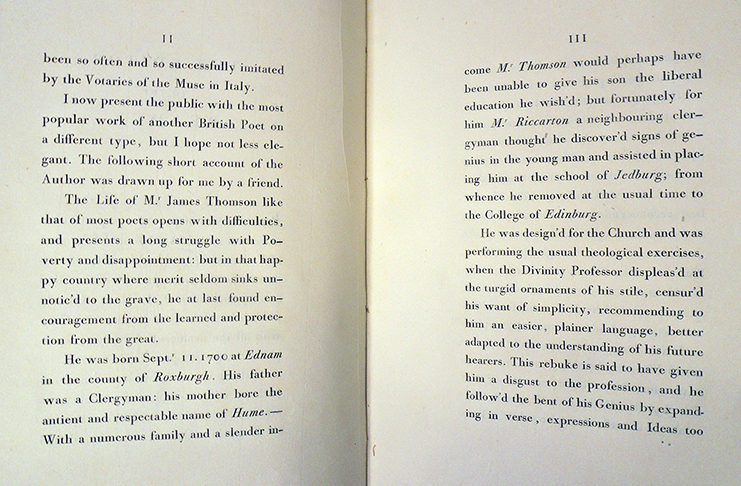

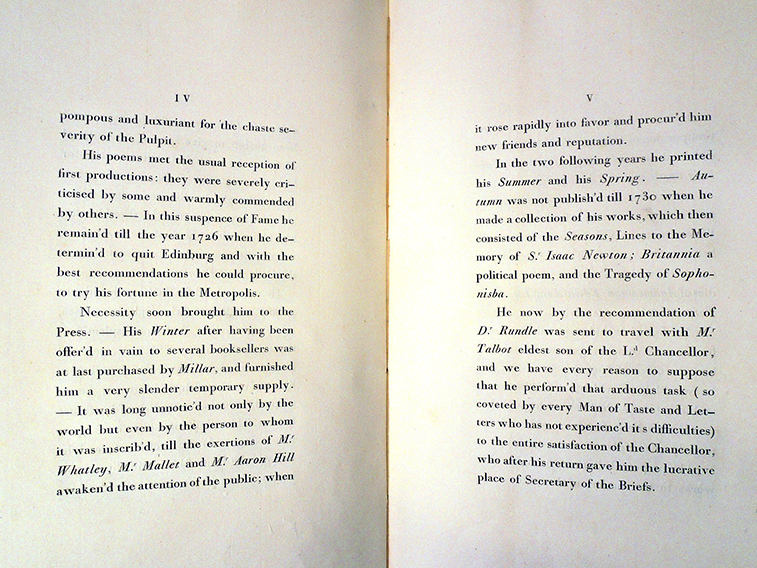

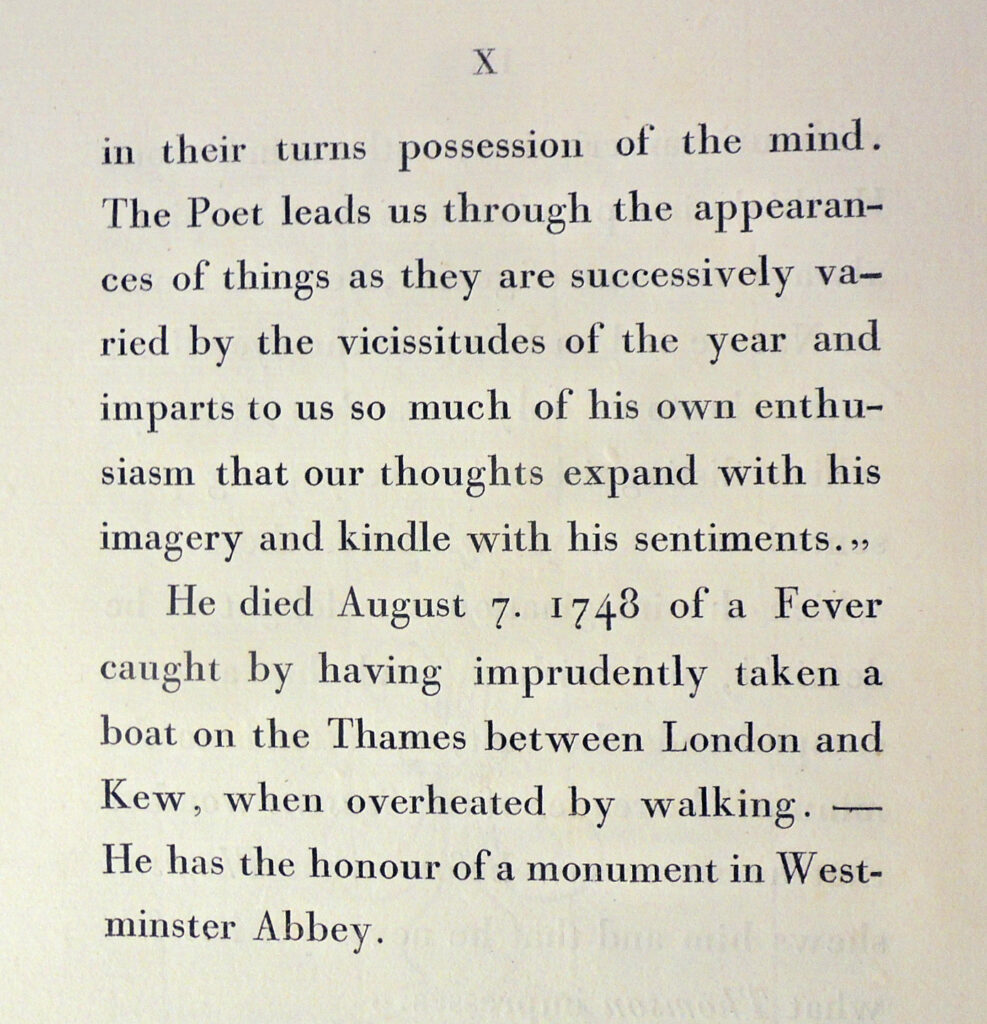

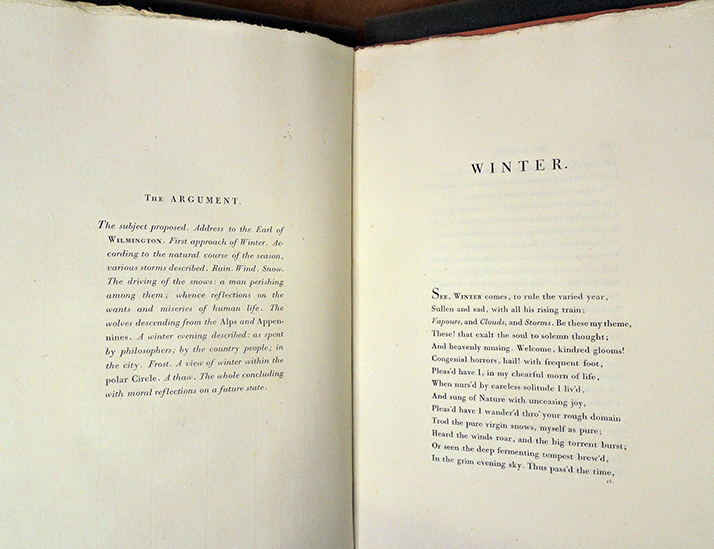

James Thomson (1700-1748), The Seasons (Parma, Bodoni, 1794). Printed by Giambattista Bodoni (1740-1813). In original orange boards. Graphic Arts Collection F-000132.

James Thomson (1700-1748), The Seasons (Parma, Bodoni, 1794). Printed by Giambattista Bodoni (1740-1813). In original orange boards. Graphic Arts Collection F-000132.

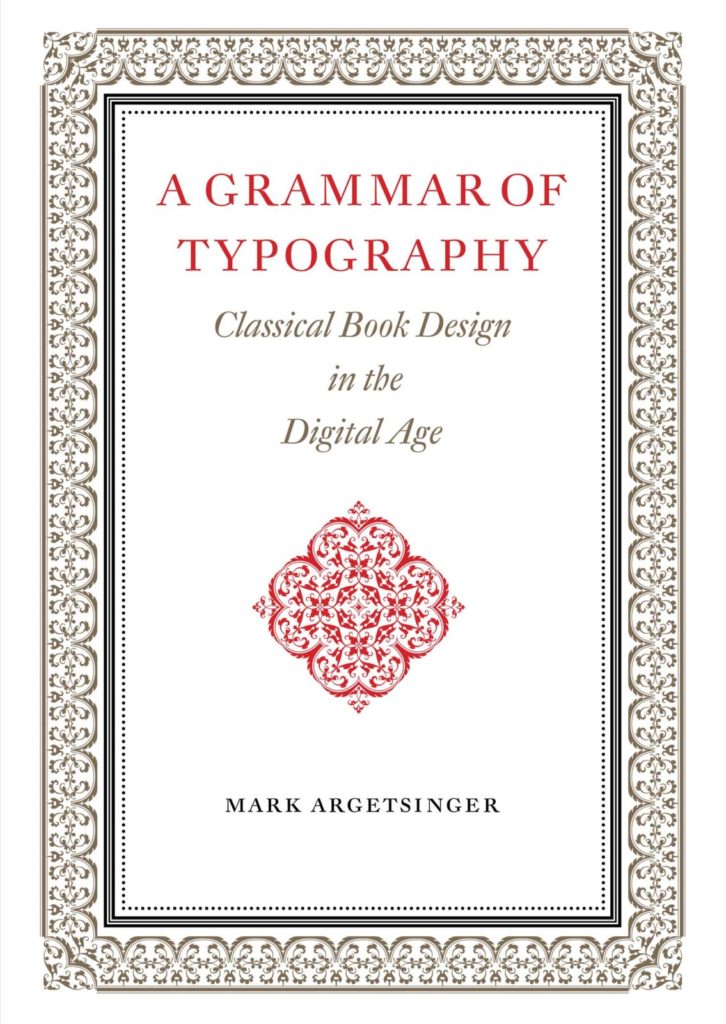

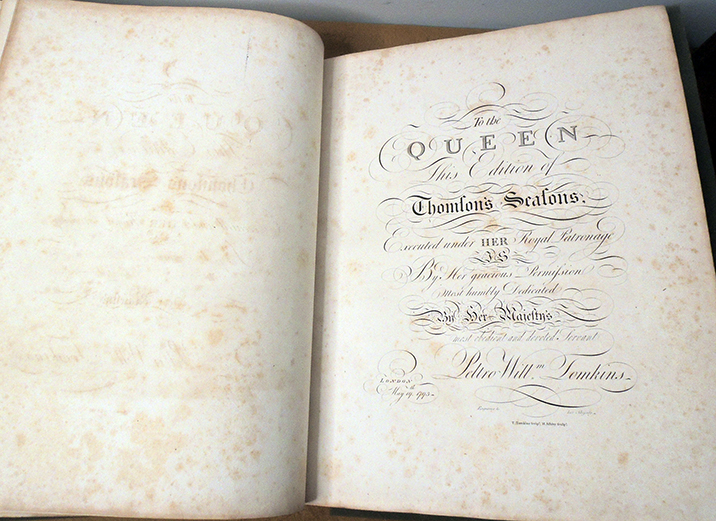

“Despite the general decline of the folio format in the second half of the century, it was revived for two editions of The Seasons, one of which was an elaborate subscription venture that took four years to complete; the other was commissioned and largely financed by Thomson enthusiast David Steuart, 11th Earl of Buchan. Catering to the upper end of the market, booksellers issued the lavishly illustrated 1797 folio edition, dedicated to the Queen, with engravings by Peltro William Tomkins and Francesco Bartolozzi.

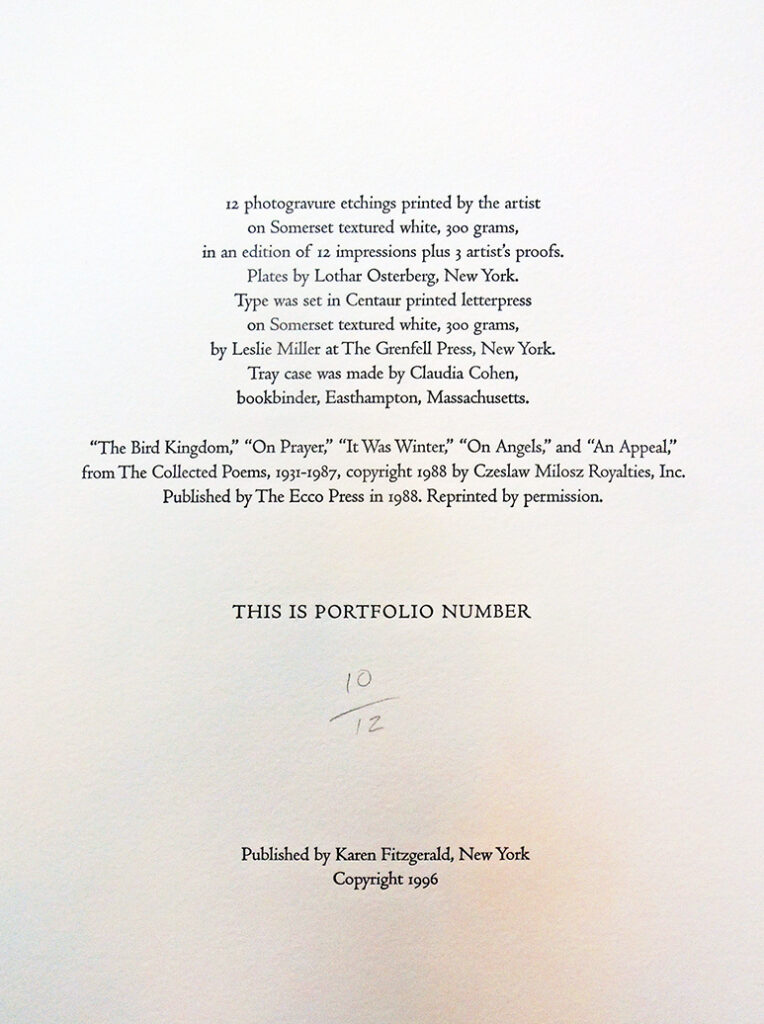

In Italy, Giambattista Bodoni published another luxurious English-language folio edition for an elite clientele in Britain, using his superb type but no illustrations; he primarily targeted a Scottish market for the work because of the growing cult of Thomson that Steuart had fostered early in the 1790s, and aimed at book collectors to purchase his edition. –Brian Hillyard, “David Steuart and Giambattista Bodoni: On the Fringes of the British Book Trade,” in Worlds of Print: Diversity in the Book Trade, edited by John Hinks and Catherine Armstrong (2006), 113-25. 8.

To prepare for a virtual student visit this week, both folio editions of Thomson’s The Seasons were pulled and some pages photographed.

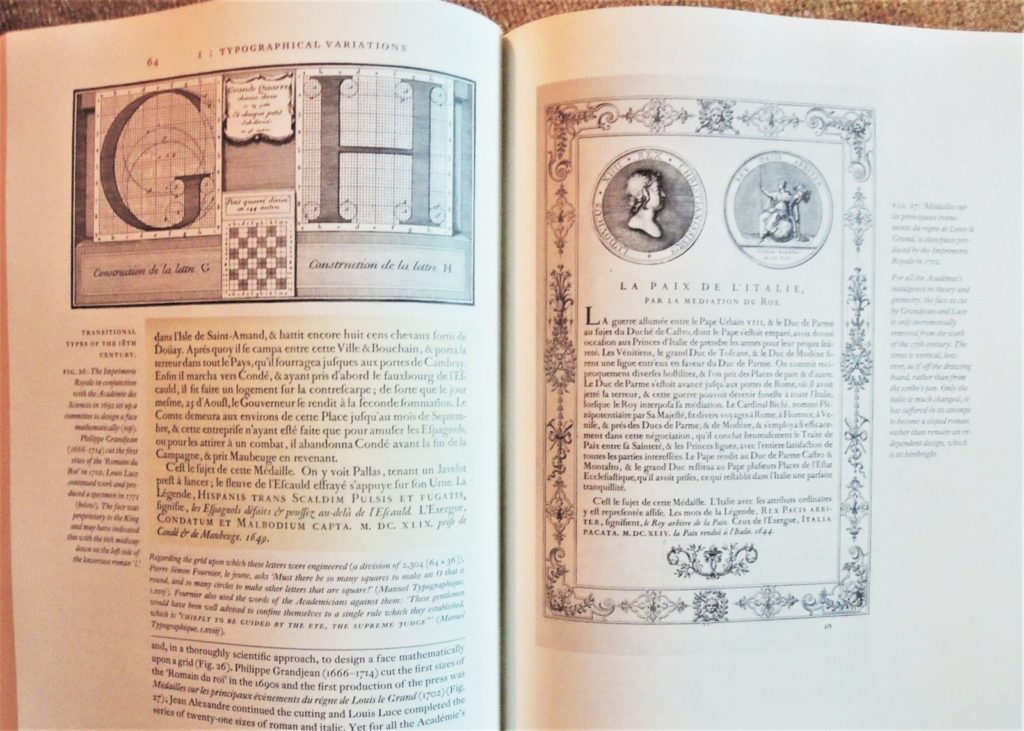

Warren E. Preece wrote a brief commentary on Bodoni, noting “In Italy, Giambattista Bodoni enthusiastically took up the principle of page design as worked out by Baskerville, though not his typefaces. Further modifying the Aldine roman of Garamond, he mechanically varied the difference between the thick and thin strokes of his letters to achieve the ultimate contrast possible in that direction. His letters are rather narrower than those of either Caslon or Baskerville. He exaggerated his thick lines and reduced the thin ones almost—it seems at times—to the point of disappearance. Like Baskerville, he used opulent papers and inks blended for special brilliance.

His pages were not easy to read, but he became, in the words of Stanley Morison, the typographical idol of the man of taste, and his “plain”—though deliberately and artfully contrived—designs were an important factor in the decline in importance of the édition de luxe and its replacement by works more austere in feeling, more modern even to today’s eyes. He set what was, in general, to be the standard book style of the world until the appearance of William Morris. Warren E. Preece, “Typography,” Encyclopædia Britannica

As is widely noted, William Morris considered Bodoni’s mechanical typography an example of “modern ugliness.”

Bodoni also set the standard for printing the alphabet with his Manuale tipografico (1818). The two-volume set features 142 sets of roman and italic typefaces, a wide selection of borders, ornaments, symbols, and flowers, as well as Greek, Hebrew, Russian, Arabic, Phoenician, Armenian, Coptic, and Tibetan alphabets (Graphic Arts Collection Q-000122).

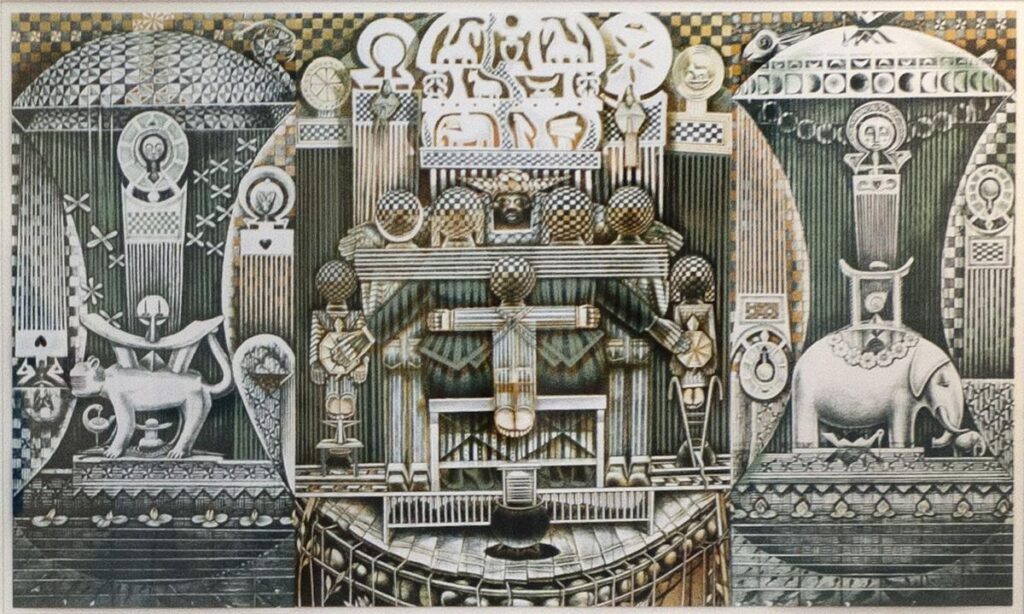

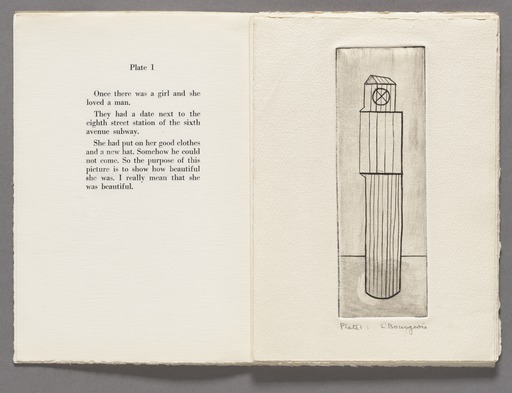

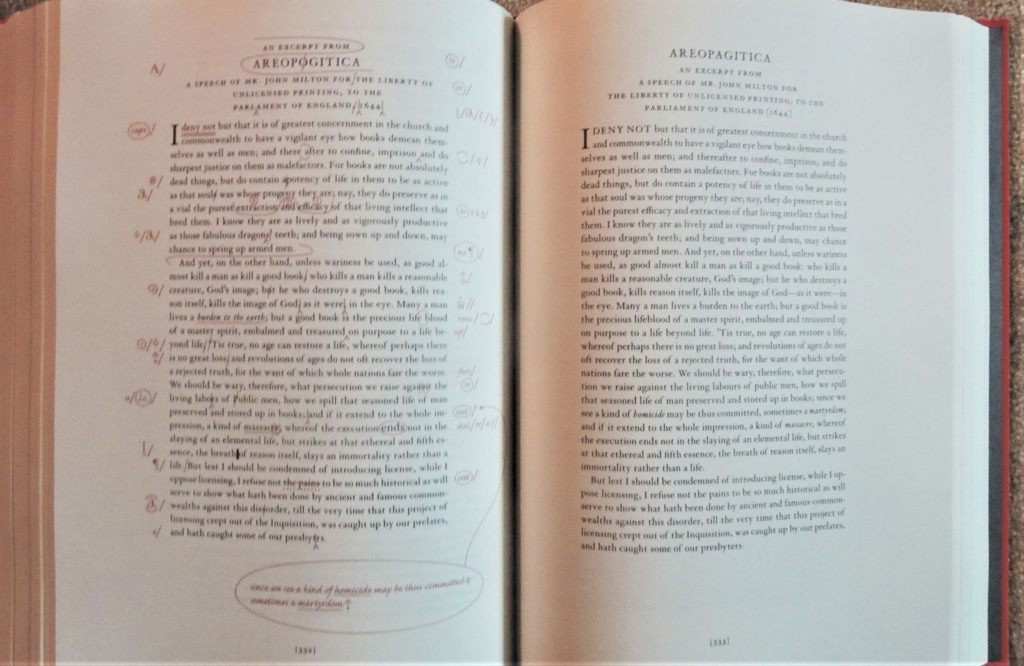

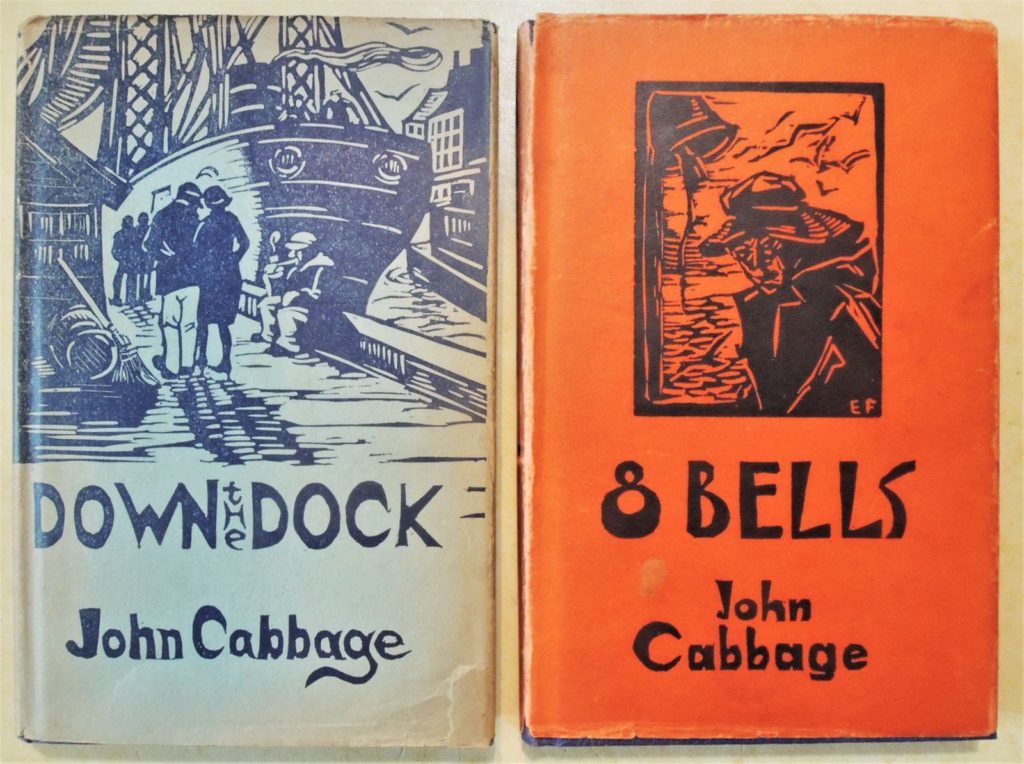

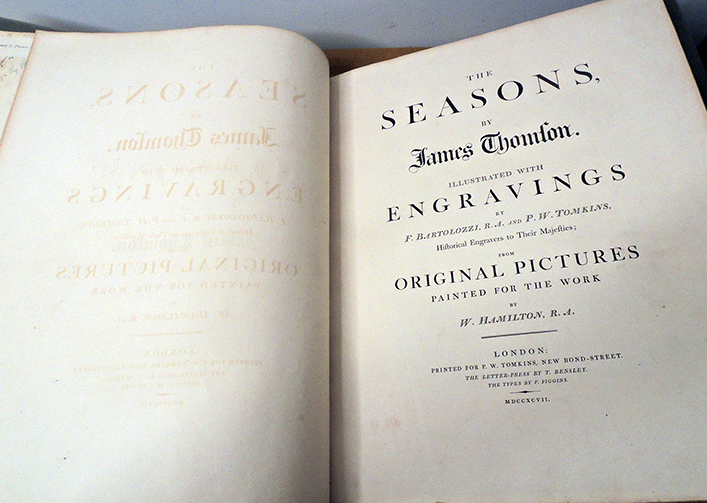

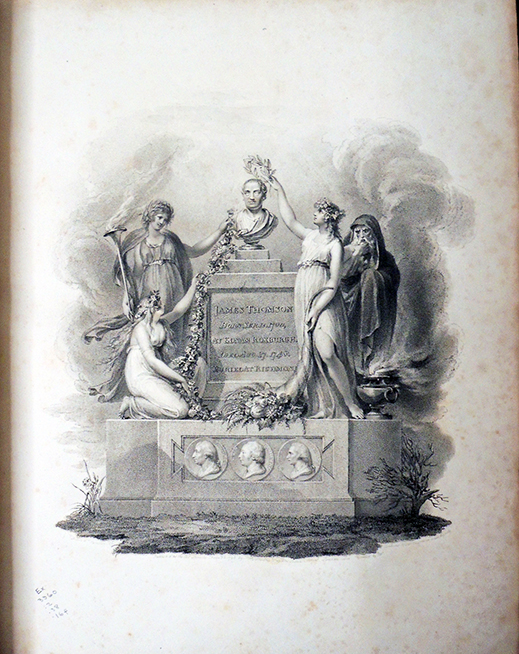

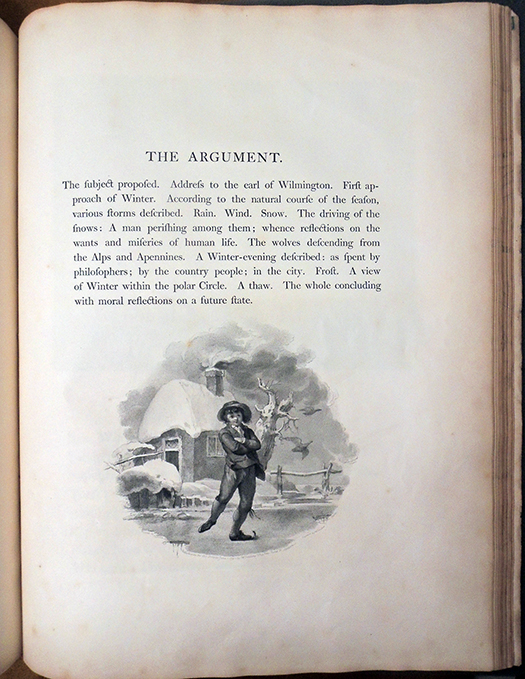

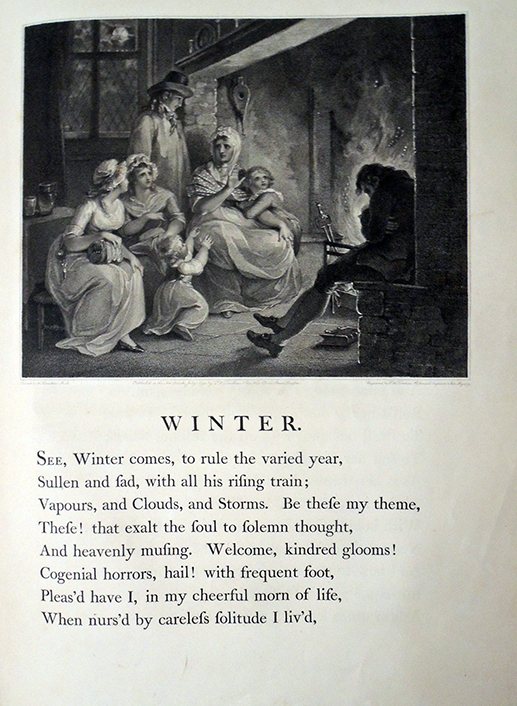

James Thomson (1700-1748), The Seasons. Illustrated with engravings by F. Bartolozzi, R.A. and P.W. Tomkins, historical engravers to Their Majesties; from original pictures painted for the work by W. Hamilton, R.A. (London: Printed for P.W. Tomkins, 1797). Rare Books Oversize 3960.2.38.16f

James Thomson (1700-1748), The Seasons. Illustrated with engravings by F. Bartolozzi, R.A. and P.W. Tomkins, historical engravers to Their Majesties; from original pictures painted for the work by W. Hamilton, R.A. (London: Printed for P.W. Tomkins, 1797). Rare Books Oversize 3960.2.38.16f

In contrast with Bodoni’s Seasons, a lavish edition of The Seasons was prepared by Peltro William Tomkins, who commissioned paintings by William Hamilton (1751-1801), which were translated to engravings by Francesco Bartolozzi (1727-1815) and Peltro William Tomkins (1759-1840). Targeted at the Scottish market, this edition was enthusiastically promoted and sold well into the early 19th century.

Natashia Troubetskoia, Anaïs Nin, ca. 1932. Oil on canvas. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution

Natashia Troubetskoia, Anaïs Nin, ca. 1932. Oil on canvas. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution