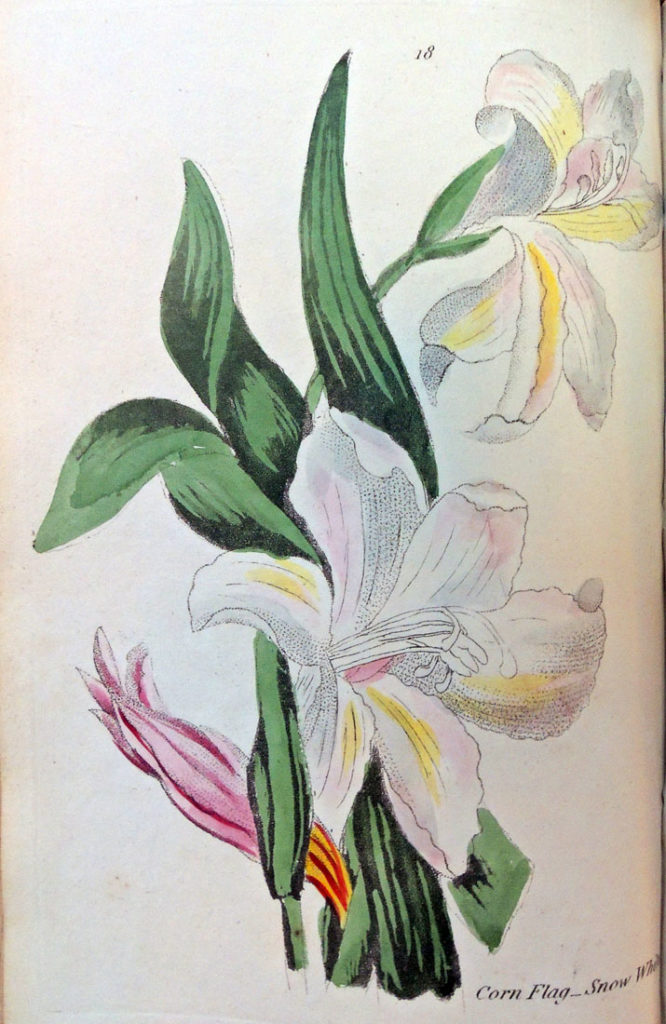

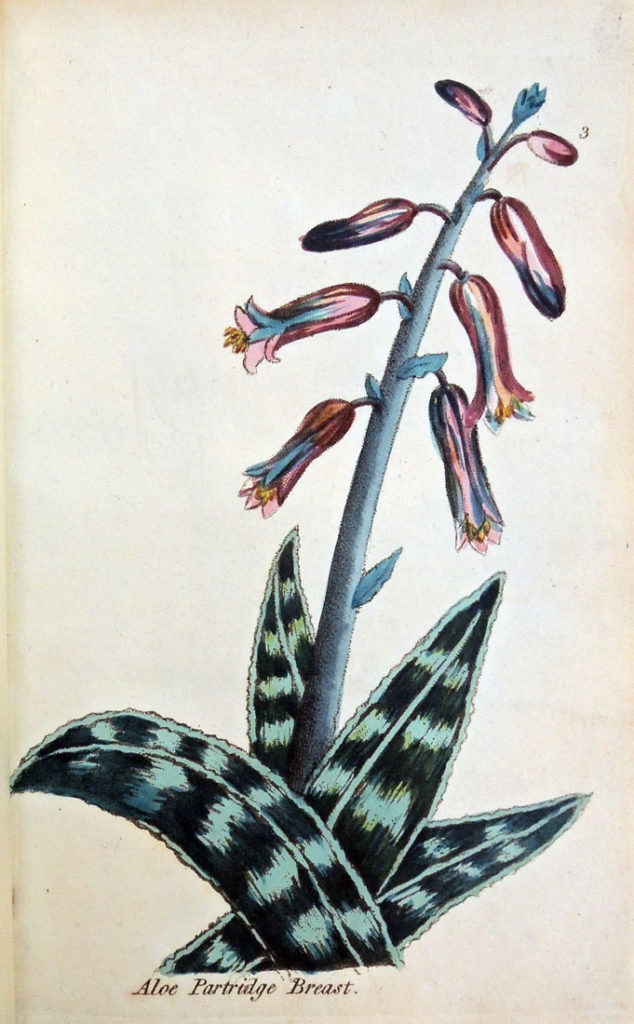

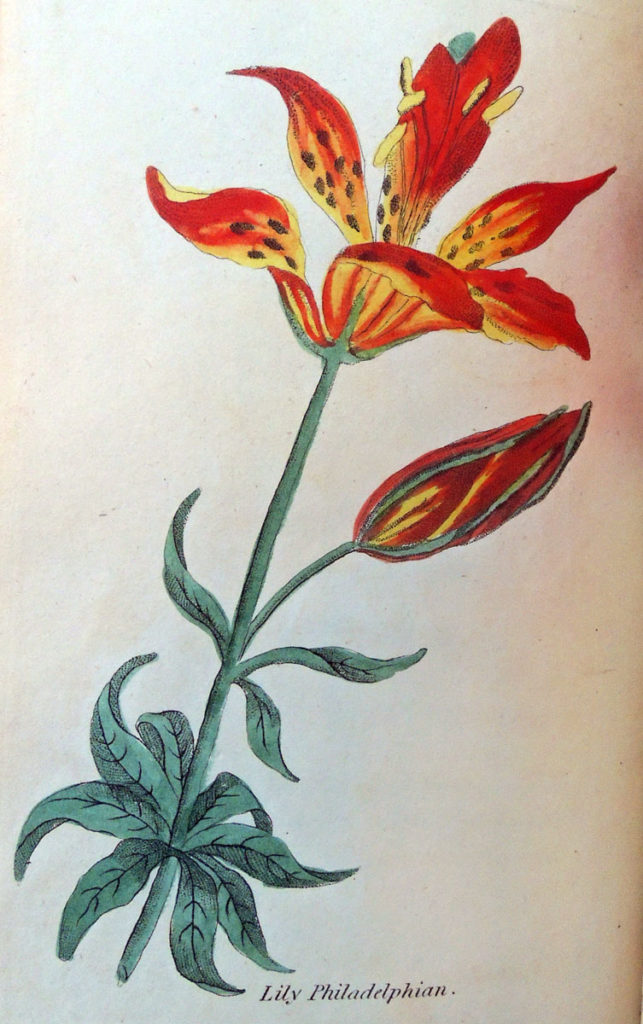

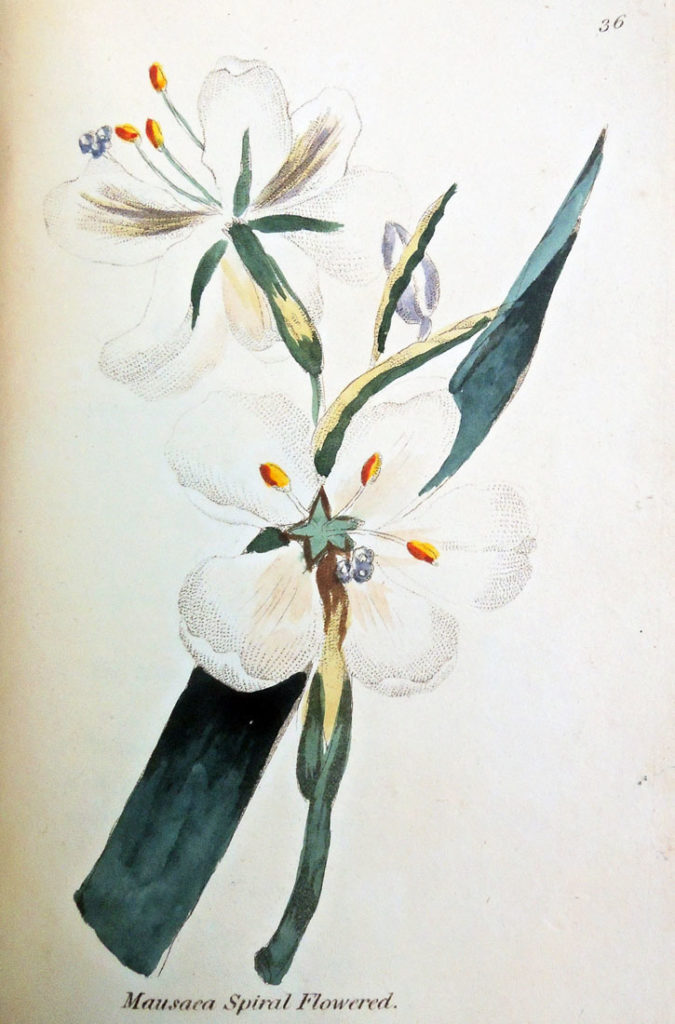

Henrietta Maria Moriarty (1781-1842), Viridarium: Coloured Plates of Greenhouse Plants, with Linnean Names, and with Concise Rules for Their Culture (London: Printed by Dewick & Clarke, Aldergate-Street, for the Author; and sold by William Earl, No. 47, Albemarle-Street, Piccadilly. 1806). First edition. 50 handcolored aquatint plates, each accompanied with a corresponding leaf of descriptive text. Graphic Arts Collection GAX 2018- in process.

Henrietta Maria Moriarty (1781-1842), Viridarium: Coloured Plates of Greenhouse Plants, with Linnean Names, and with Concise Rules for Their Culture (London: Printed by Dewick & Clarke, Aldergate-Street, for the Author; and sold by William Earl, No. 47, Albemarle-Street, Piccadilly. 1806). First edition. 50 handcolored aquatint plates, each accompanied with a corresponding leaf of descriptive text. Graphic Arts Collection GAX 2018- in process.

In his post Avoiding sex with Mrs Moriarty, garden historian Dr. David Marsh writes that facts concerning Moriarty’s life have been elusive. She traveled in high class circles: the book’s subscription list is headed by Prince Augustus, the Duke of Sussex and the younger brother of George IV and William IV. The work is dedicated to Lady de Clifford, who also bought five copies.

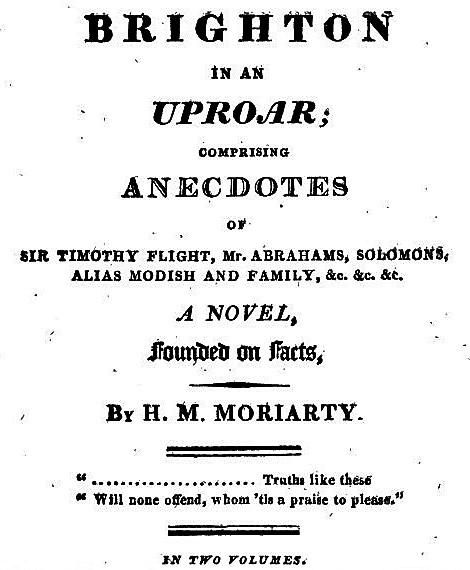

The plates are mainly copied from Curtis’s Botanical Magazine so it leaves open the question of why this work came to press. Thanks to research by our friends at Marlborough Books, we now have answers about who Moriarty really was. They found a novel by Moriarty, published in 1811 under the title Brighton in an Uproar, and writes:

“This is very clearly an autobiographical work in which she uses the nom de plume of ‘Mrs Mortimer.’ Unfortunately this ‘novel’ also seems to have caused her downfall and imprisonment for slander. This connection has apparently eluded research so in case anyone wants to delve further into the mystery of Mrs Moriarty we thought to give at least an outline of her life.”

In Brighton in an Uproar, Moriarty relates why Viridarium came to be written.

Mrs. Mortimer advertised for two or three ladies to board with her: she succeeded in procuring one; and the aunt of one of the officers belonging to the corps in which her husband had served also came to reside with her. Mrs. Forth was a lady of great accomplishments, aid most pleasing manners: her behaviour to Hubertine and her children was such as rendered her an invaluable friend, and meeting with such an inmate was a great blessing to Mrs. Mortimer in her present distressed situation.

. . . Drawing had always been a favourite occupation with her; and she was advised to publish a botanical work by subscription. She was averse to this as she knew her abilities were not equal to such a task; but as it was expected of her, she immediately set about it . . . Another strong inducement to publish by subscription was the ardent desire which she had to liquidate her late husband’s debts; and in this she succeeded as from her exertion’s she paid them all within two year’s amounting to the sum of four hundred and eighty pounds.

Marlborough’s research continues,

“Henrietta Maria was christened on the 22 February 1781 at Romsey in Hampshire. She was the daughter of Major Benjamin Godfrey of the Inniskilling Dragoons and his wife Henrietta. On the 9th July 1796 she married Matthew Moriarty, Esq., of Chatham in Kent and then a Major in the Marines, she would have been barely 15 at the time of her marriage and presumably this was through the consent of her now widowed mother. Unfortunately he was not a good husband, he left a trail of debt and died somewhat dissolute, and worse leaving his widow and children unprovided for.

In order to clear the debts she wrote Viridarium and later also two novels. . . As a widow Henrietta was not reconciled to her Irish relatives and despite trying to make ends meet by writing she was clearly in financial trouble, worse she seems to have slandered someone and was committed to the King’s Bench prison in December 1813. Her occupation as a boarding house keeper, seems slightly desperate and maybe it is not surprising that she is not acknowledged in print from this time forth except the sad record contained in the 1841 census that she was a ward of the Kensington Union Workhouse followed by her death a year later.”