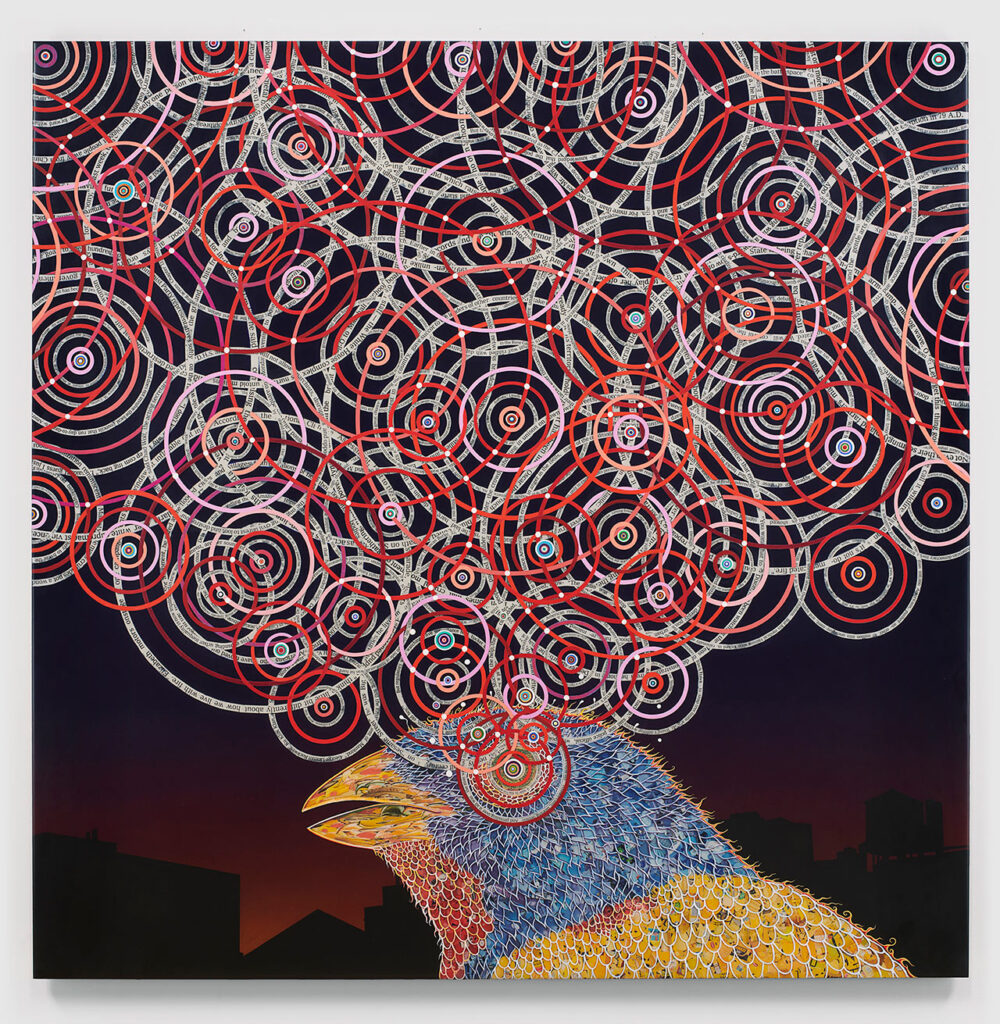

In honor of the 35th Biennial Congress of the International Association of Paper Historians (IPH) co-hosted by the Library of Congress, the National Gallery of Art, and the National Archives and Records Administration, currently in progress online, here is a reposting of the unusual collection of watermarks collected by Dawson Turner. This is physically in Princeton’s Graphic Arts Collection and digitized here: http://arks.princeton.edu/ark:/88435/k930bz393

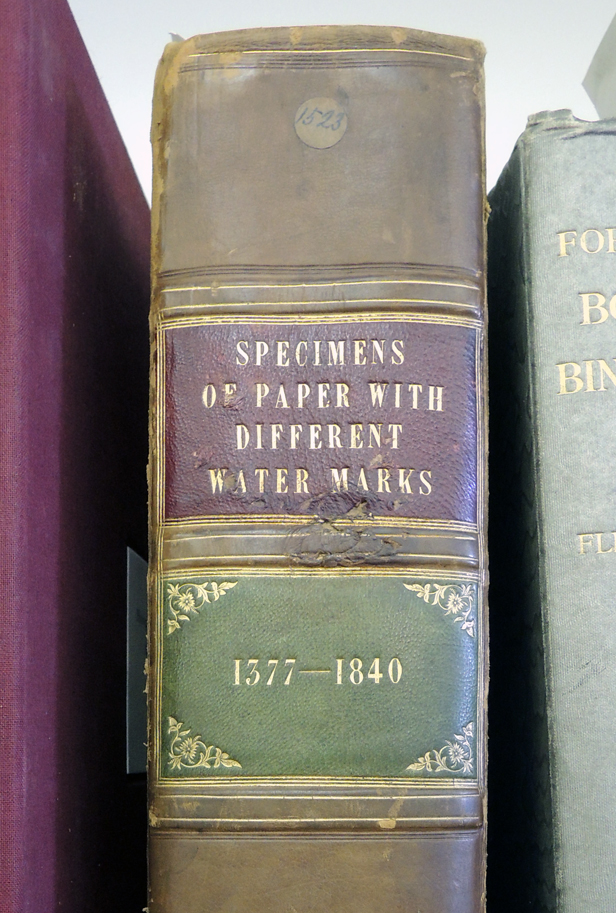

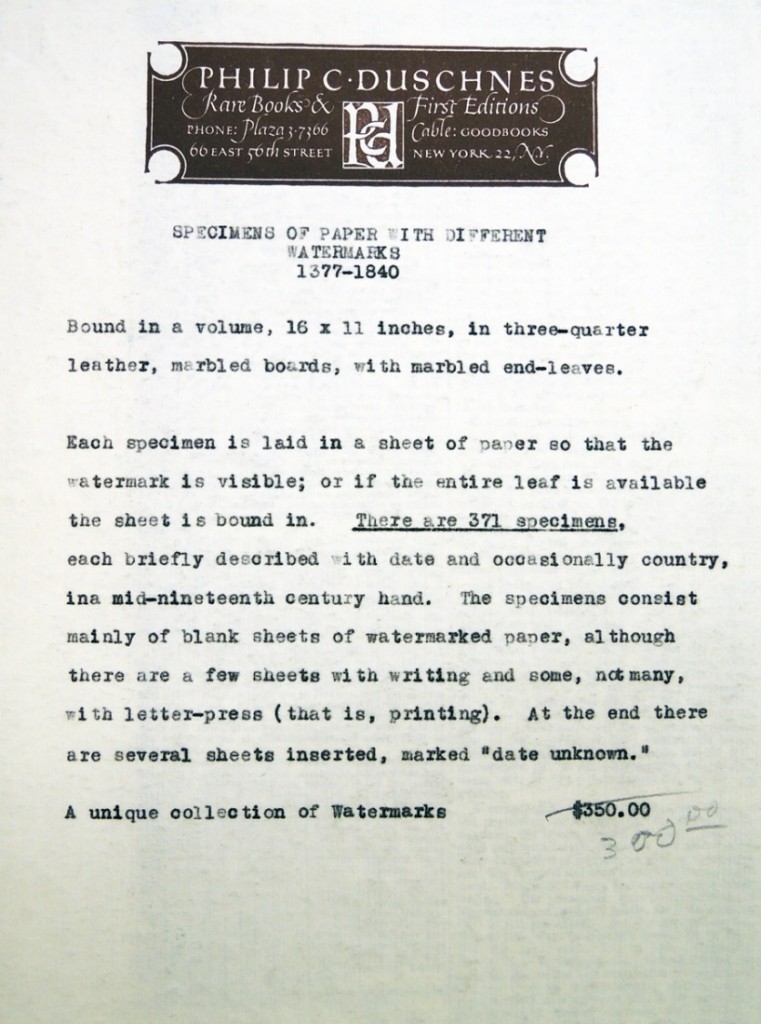

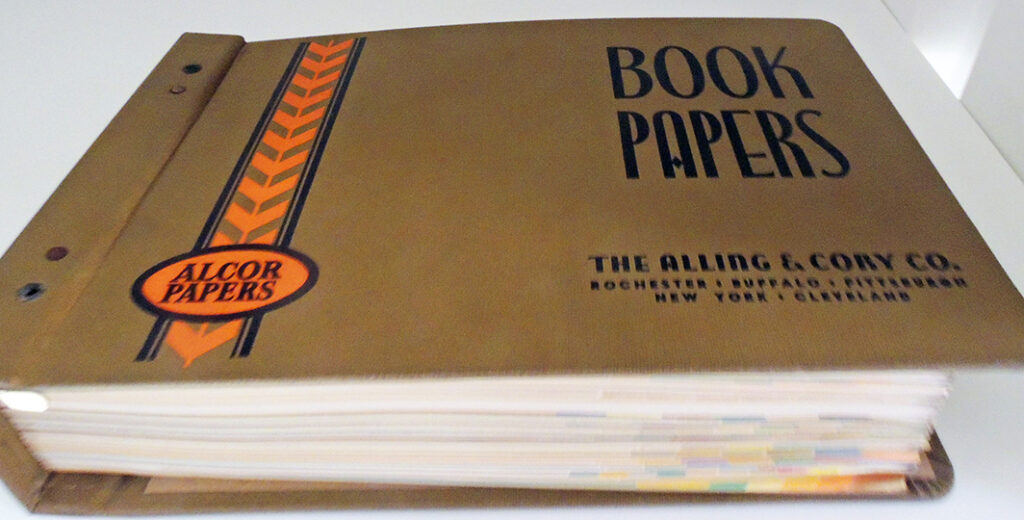

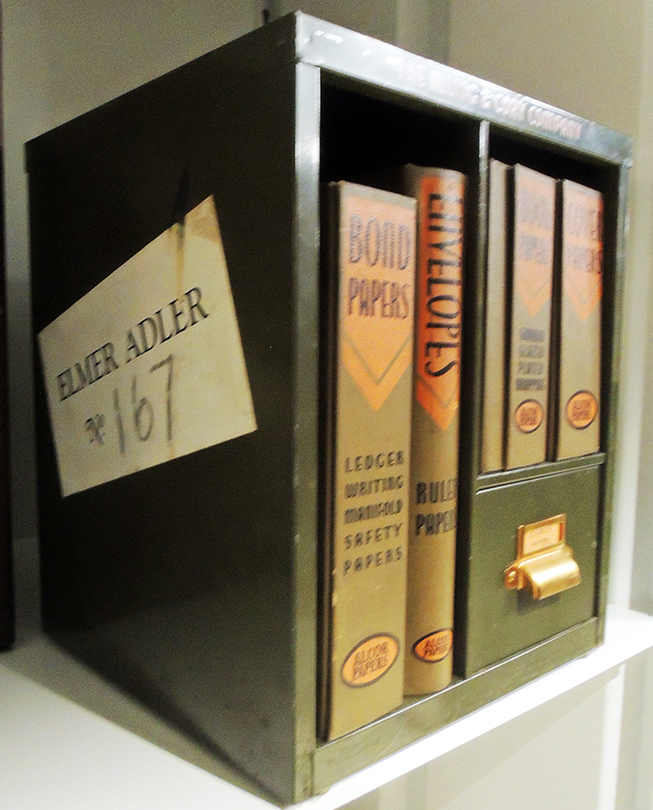

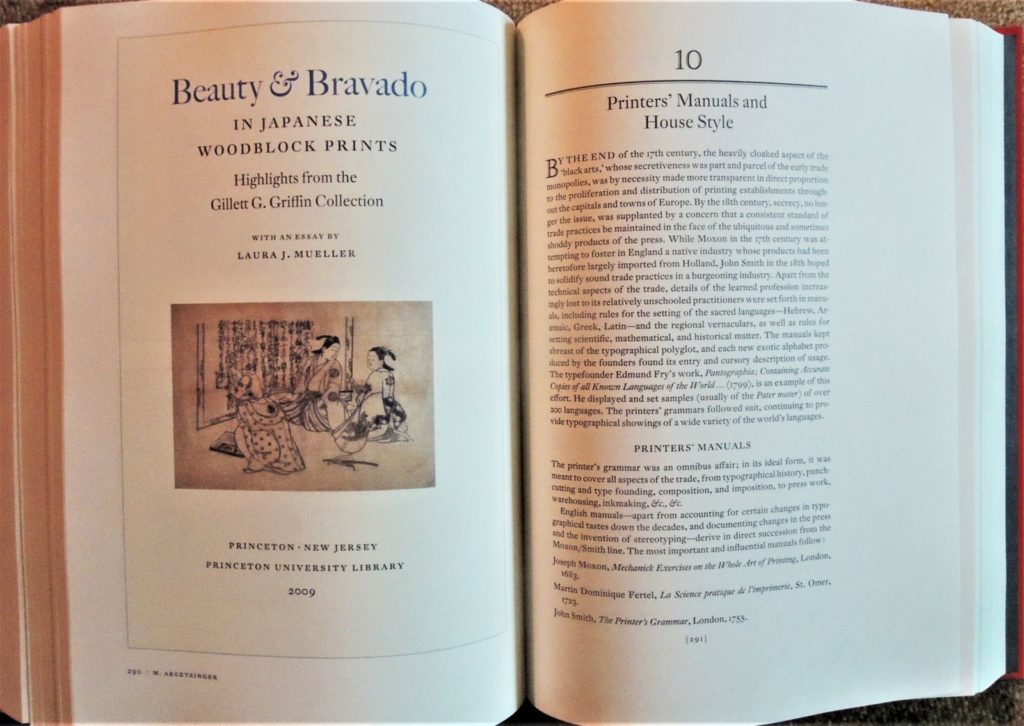

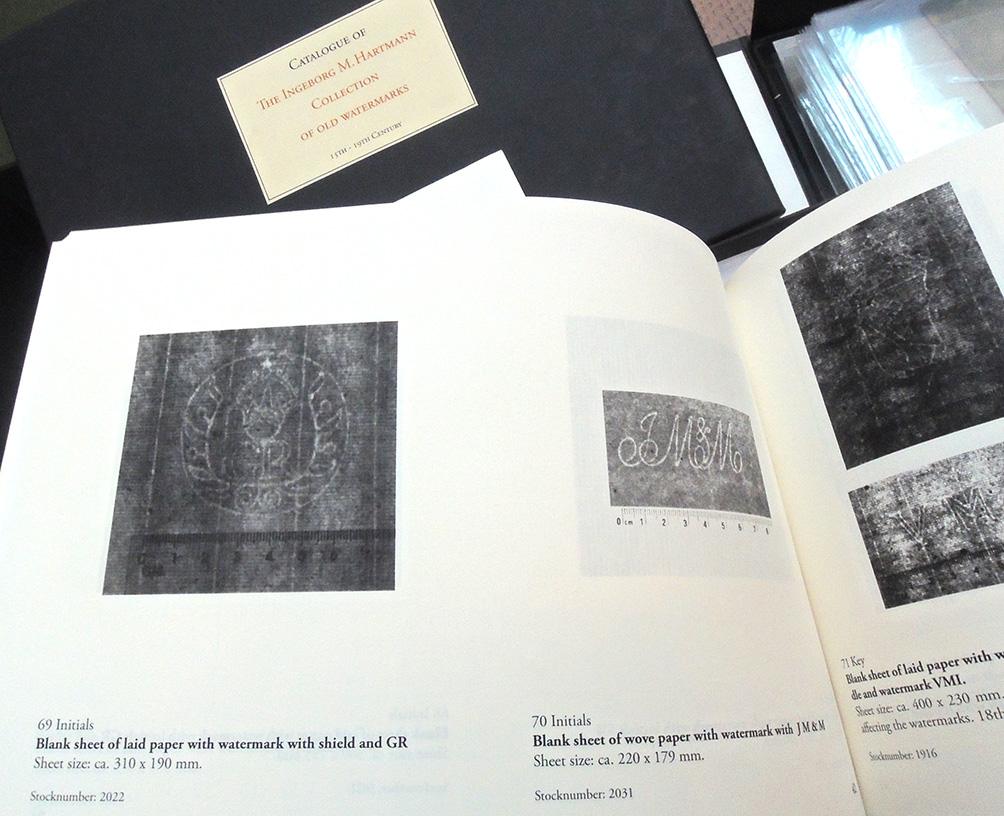

During the 1952-53 fiscal year, a unique collection of nearly 400 specimens of European papers with different watermarks (1377-1840) was acquired for the Graphic Arts Collection, at the suggestion of Elmer Adler (1884-1962) with a fund turned over to the Library by the Friends of the Princeton University Library (FPUL). Adler must have been a good negotiator, talking rare book dealer Philip Duschnes down from $350 to $300.

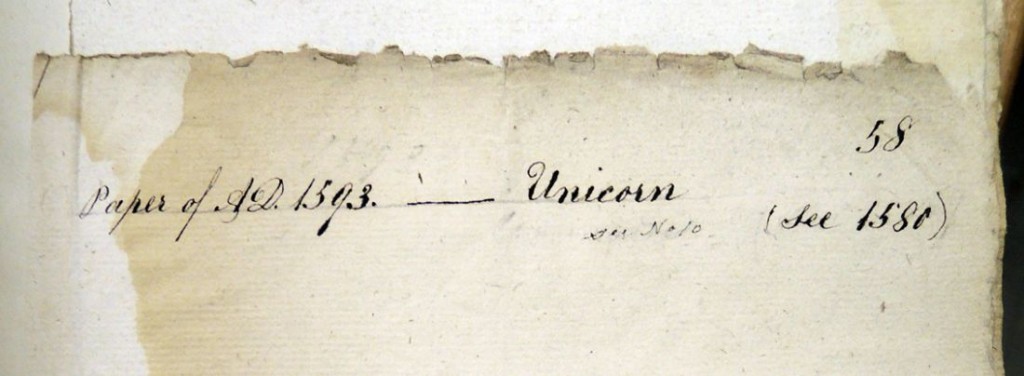

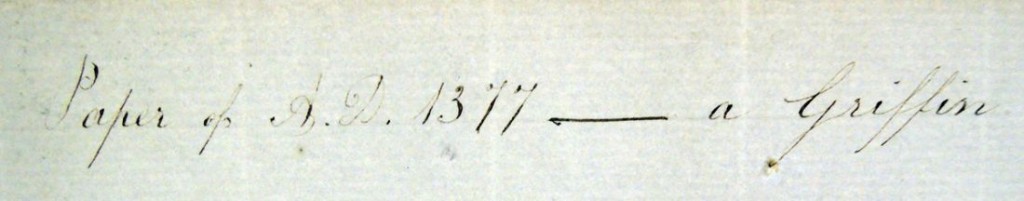

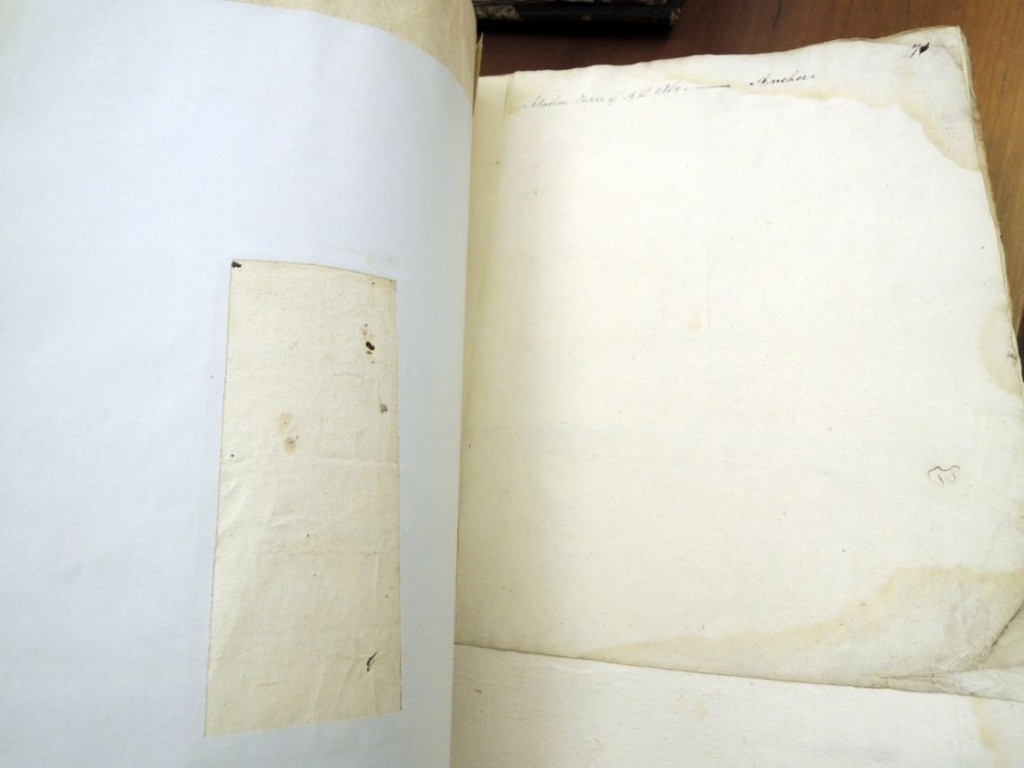

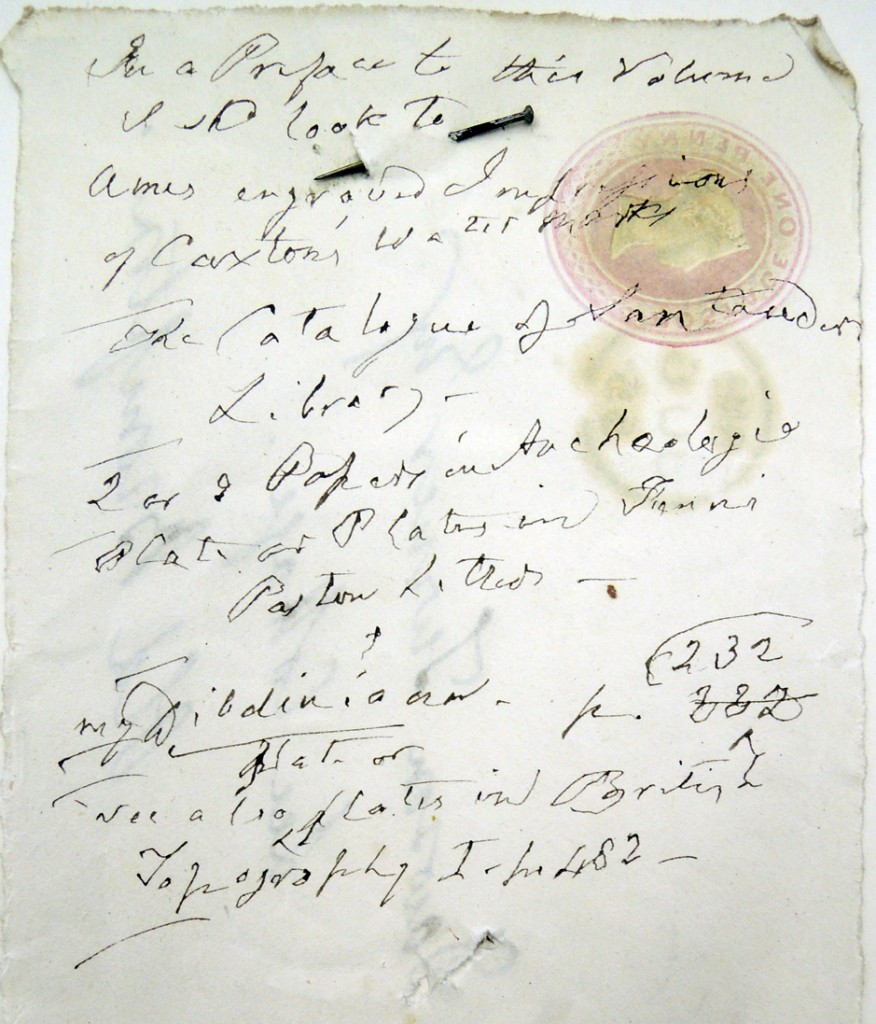

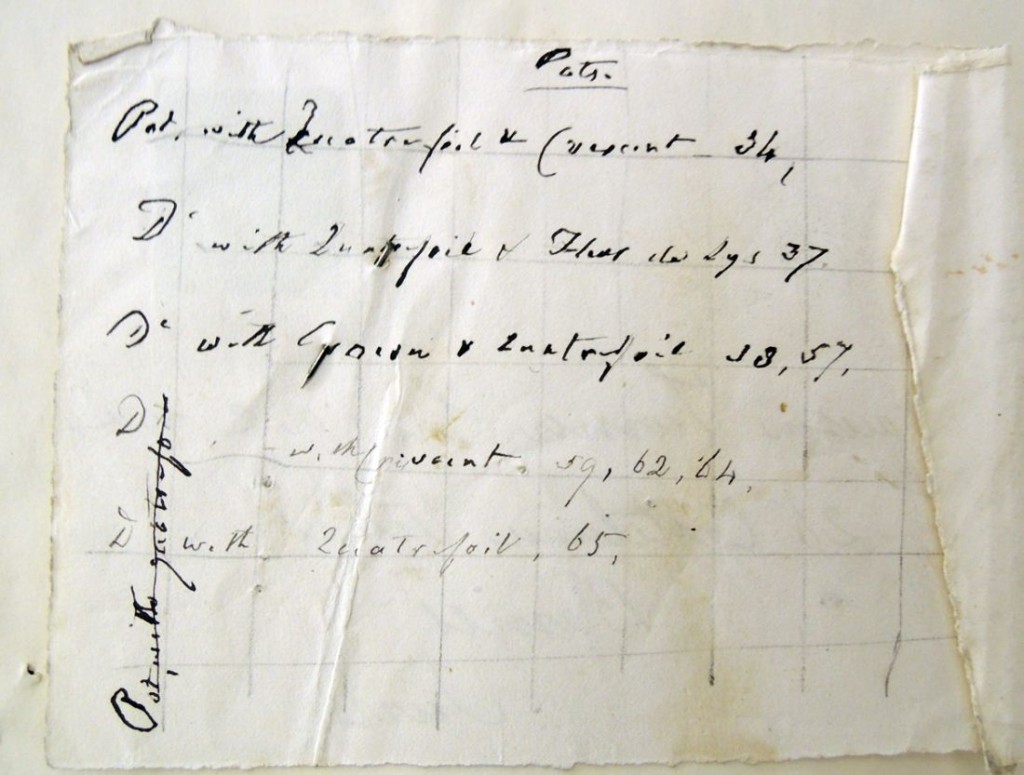

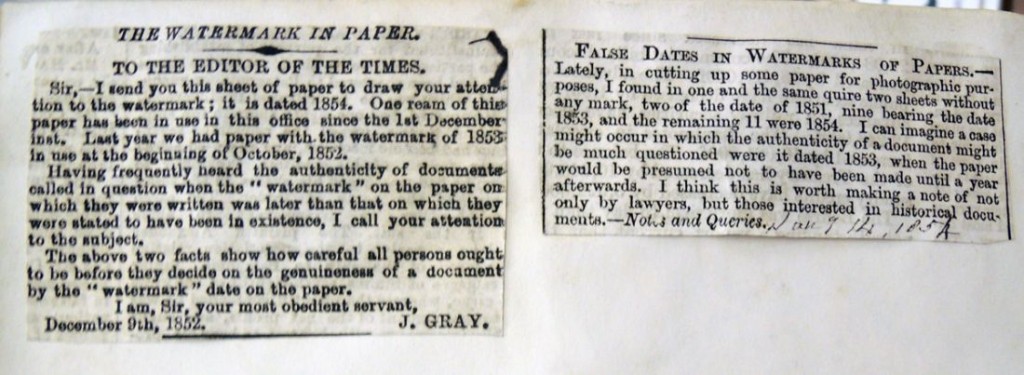

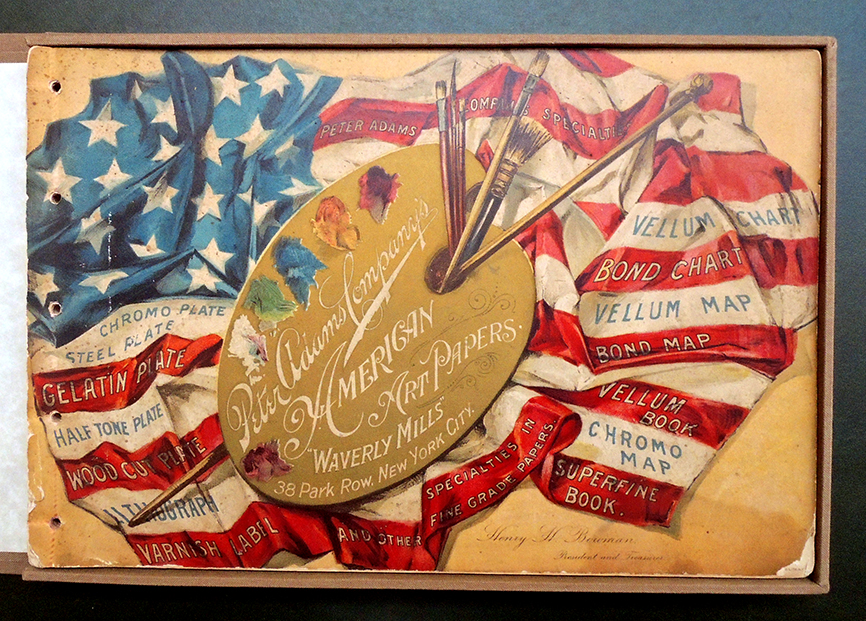

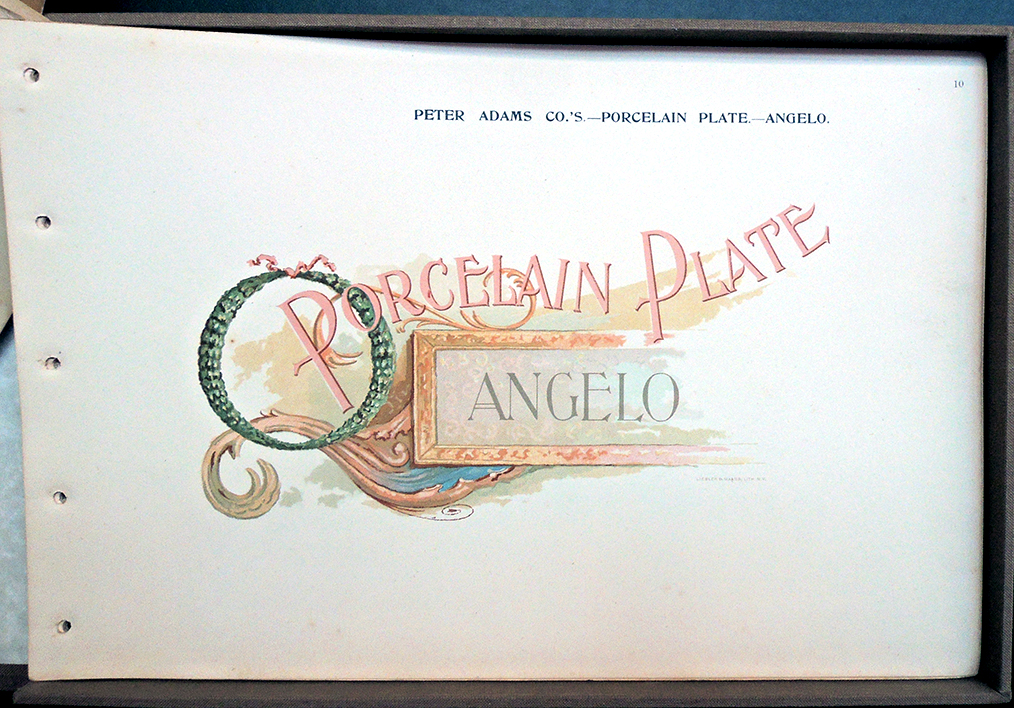

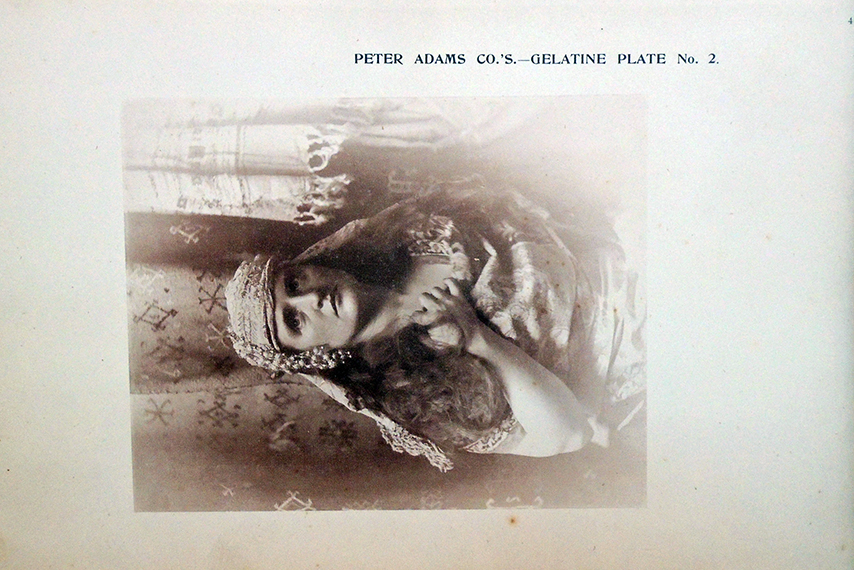

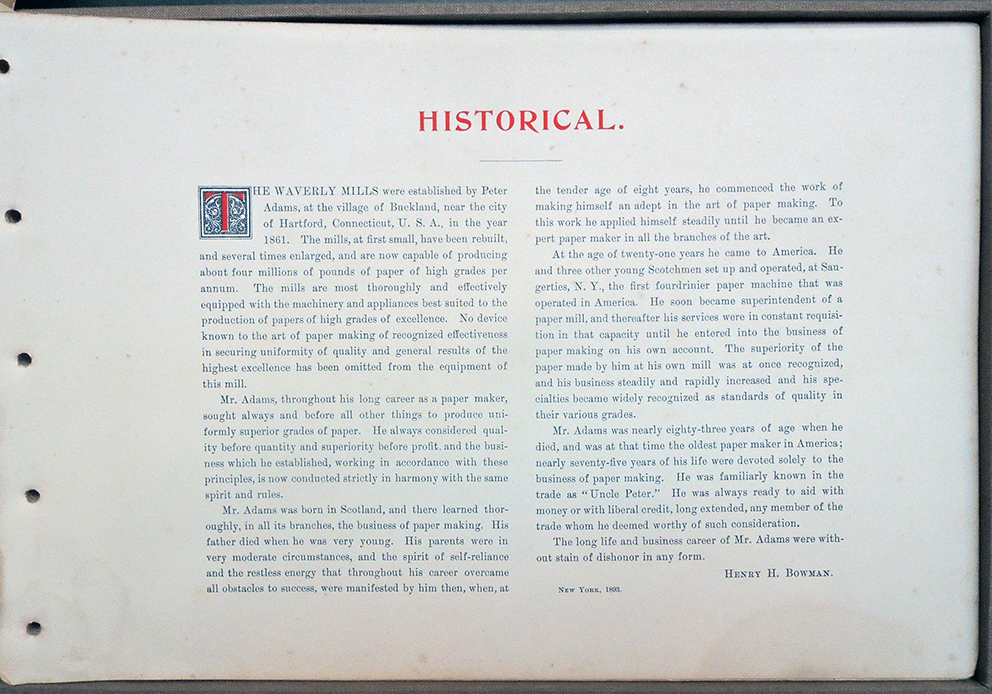

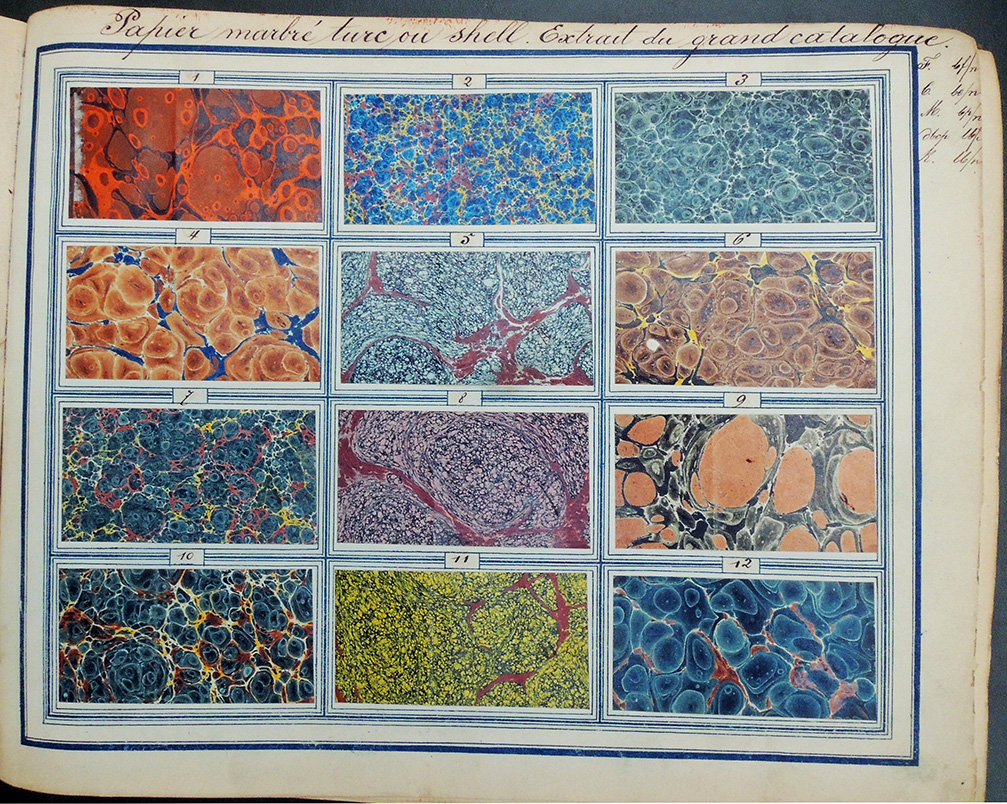

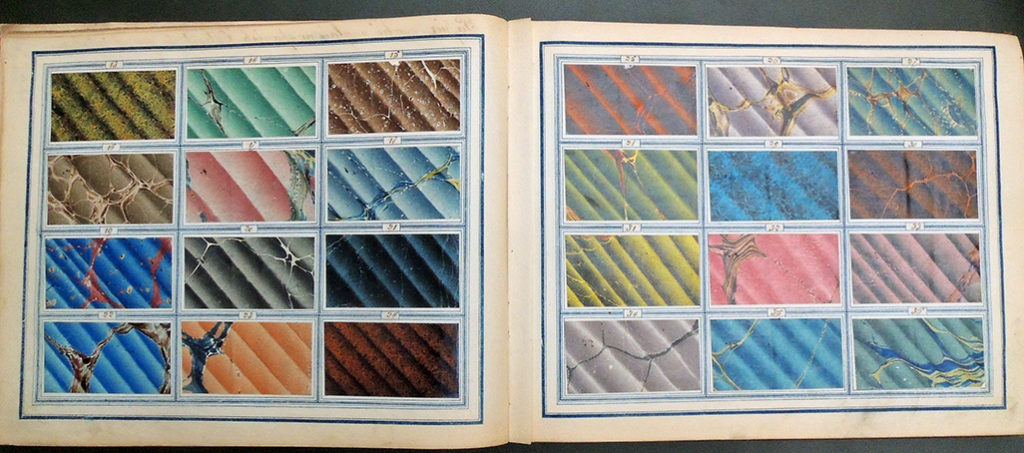

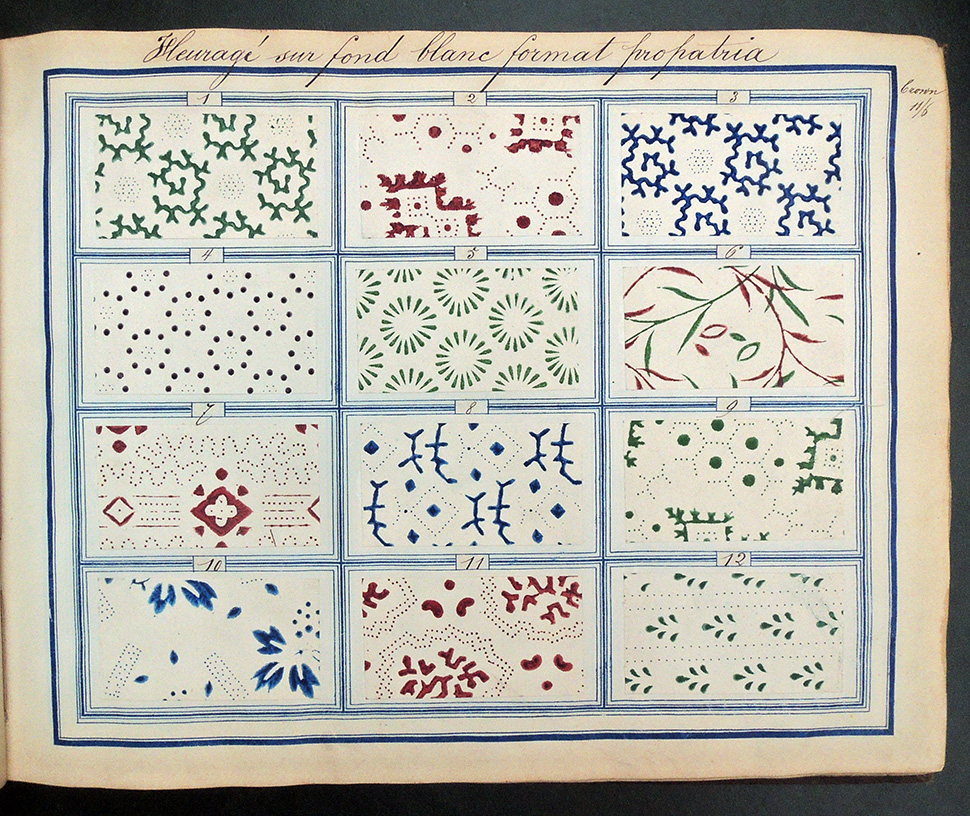

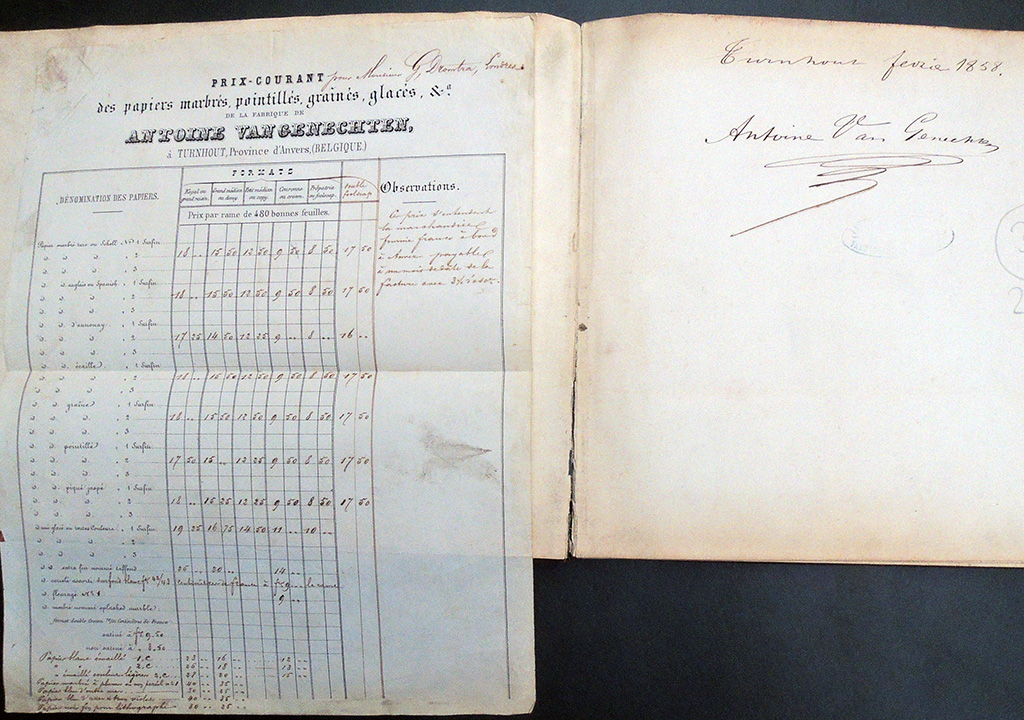

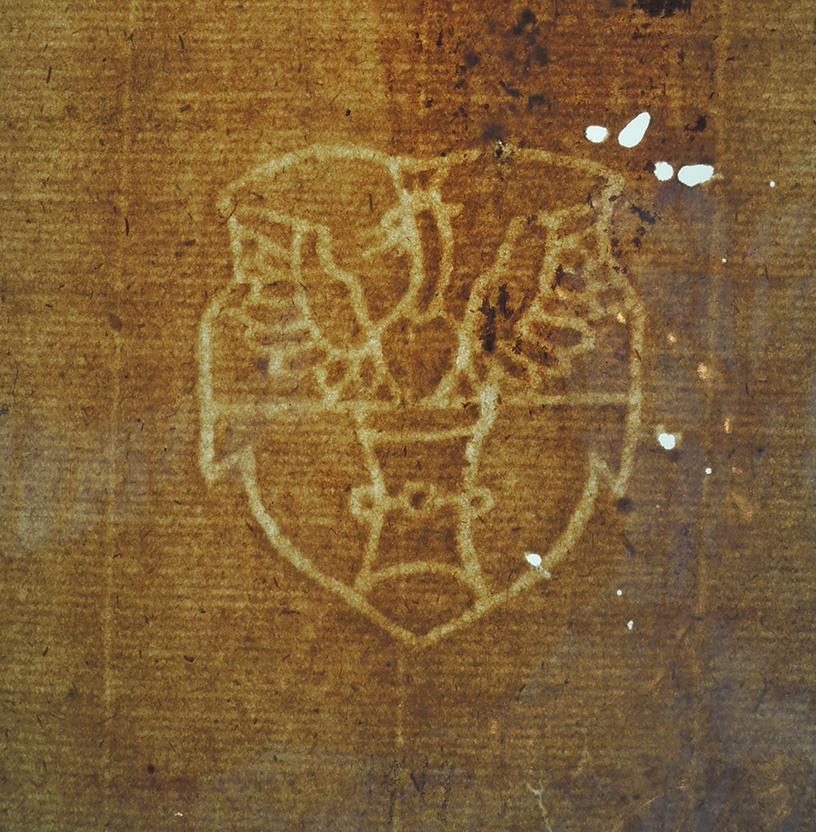

The album was elaborately created with sheets of many shapes and sizes bound in various layers, with a brief description written at the top of each sheet. I have included the front matter pinned to the endpapers.

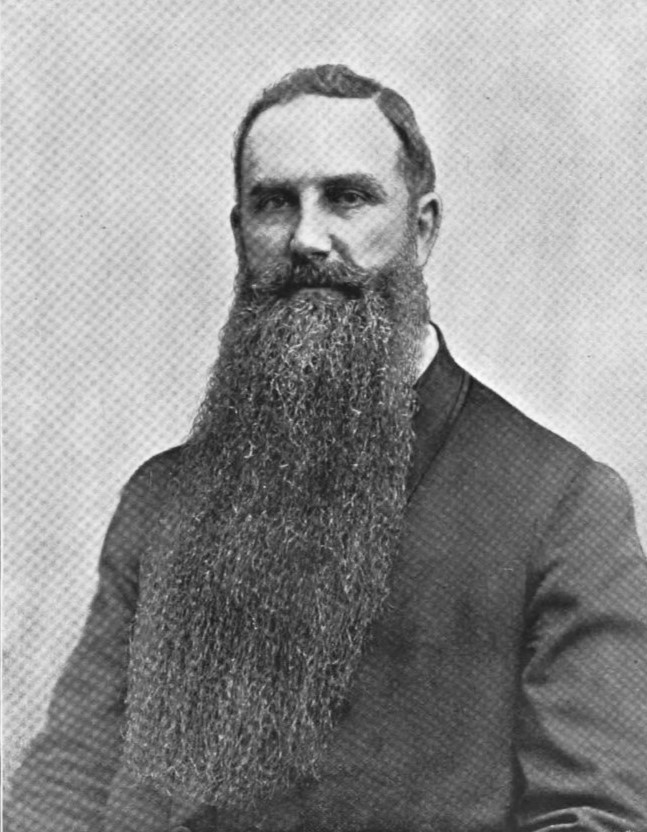

Originally in the collection of Dawson Turner (1775–1858), the auction catalogue description reads: ’Watermarks on Paper. A very curious collection of upwards of three hundred and seventy specimens of paper with various Watermarks, for A.D. 1377 to A. D. 1842, collected with a view to assist in ascertaining the age of undated manuscripts, and of verifying that of dated ones, by Dawson Turner, Esq. and bound in 1 vol. half calf.’

See also: Catalogue of the Remaining Portion of the Library of Dawson Turner, Esq., M.A., F.R.S., F.S.A., F.L.S., etc., etc. formerly of Yarmouth: which will be sold by auction by Messrs. Puttick and Simpson … Leicester Square … on Monday, May 16th, 1859, and seven following days (Sunday excepted). [London, 1859], item 1523.

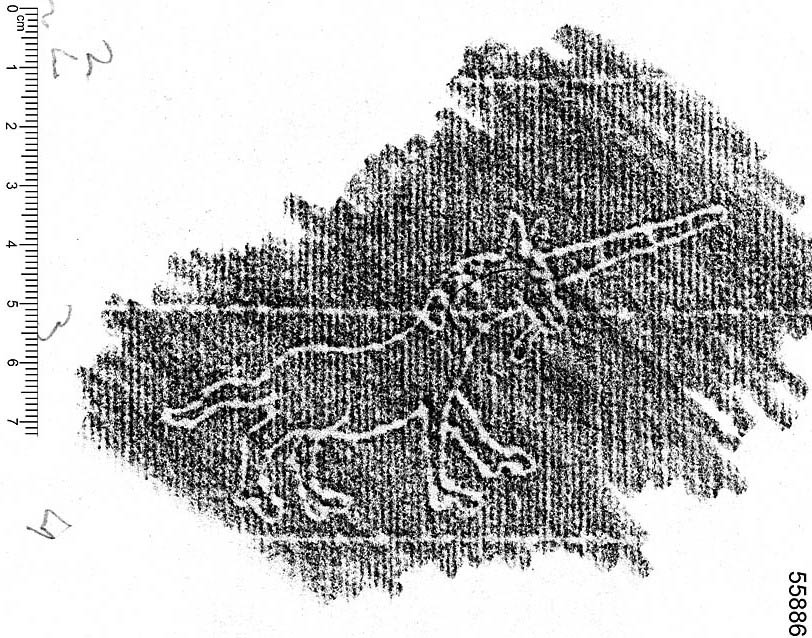

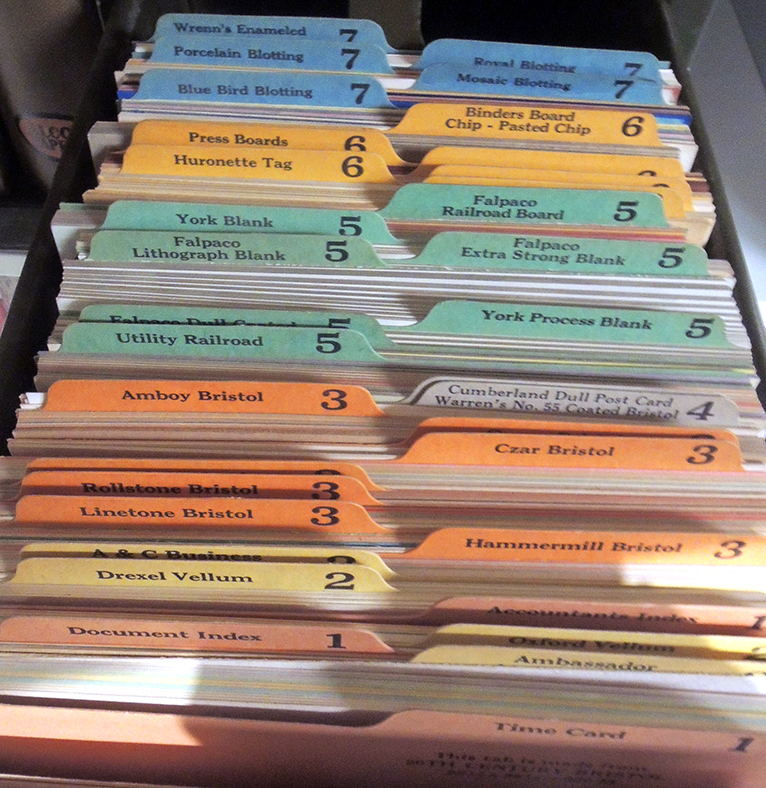

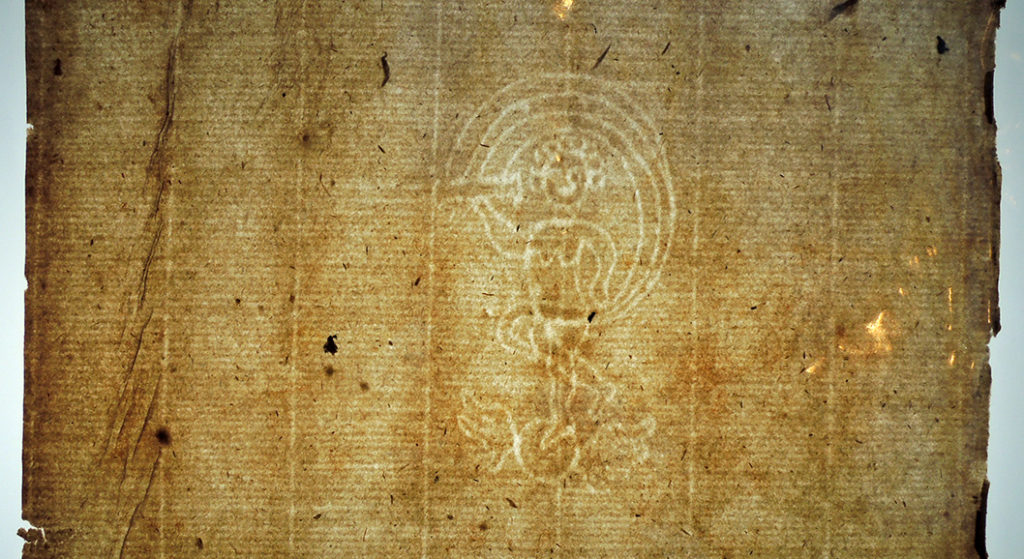

Specimens of Paper with Different Water Marks, 1377-1840. 1 v. (unpaged); 40 cm. 371 specimens of watermarked paper, together with brief descriptions of each in a mid-nineteenth century ms. hand. The specimens are mainly blank leaves, though some leaves feature writing and letterpress. Specimen 334 is stamped sheet addressed to Dawson Turner (1775-1858), Yarmouth. Purchased with funds from the Friends of the Princeton University Library. Graphic Arts: Reference Collection (GARF) Oversize Z237 .S632f

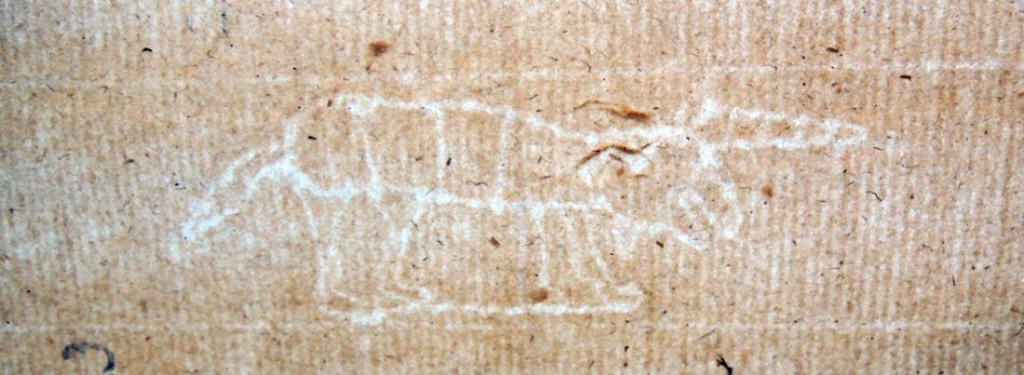

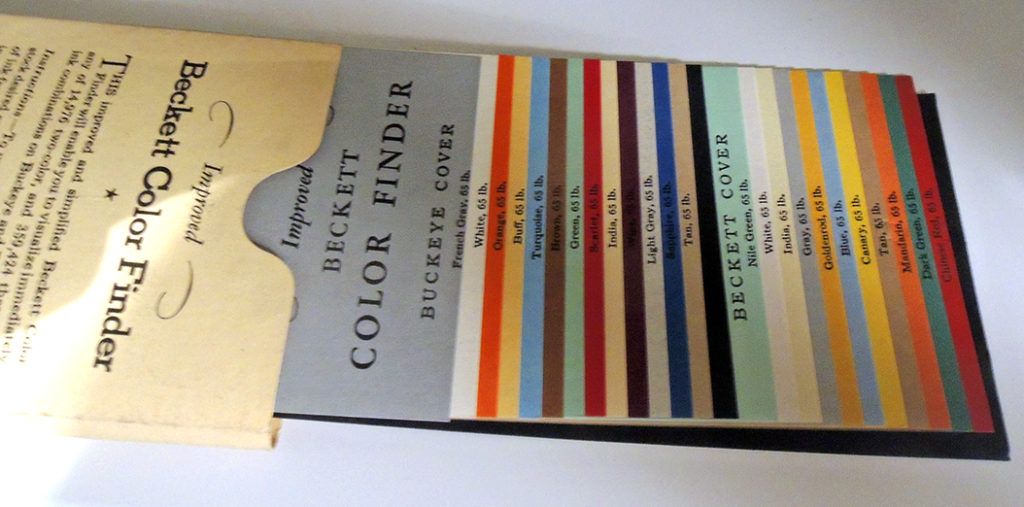

Dawson Turner may have seen a goat, but this is a definitely a Unicorn, specifically a “bearded unicorn”, with its horn removed by Victorian scissors. The date c.1440 is almost certainly wrong; a much more plausible date is mid-1470s.

Thanks very much to Paul Needham for the correction.