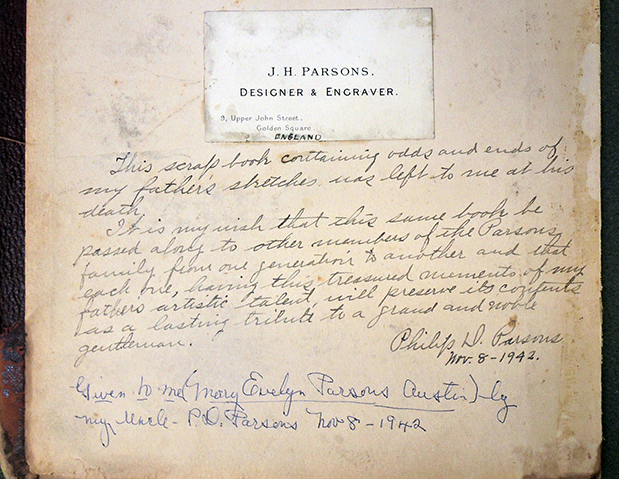

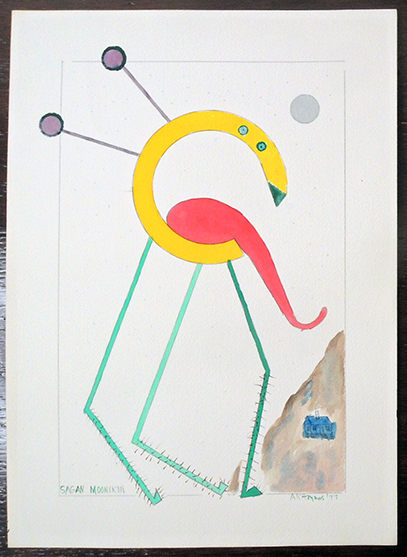

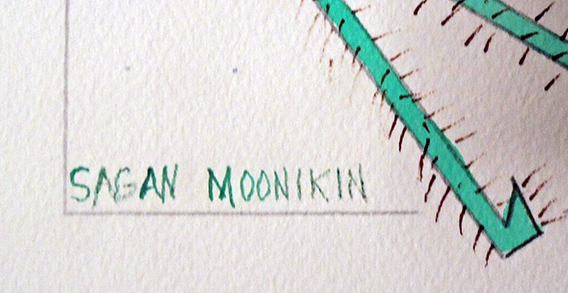

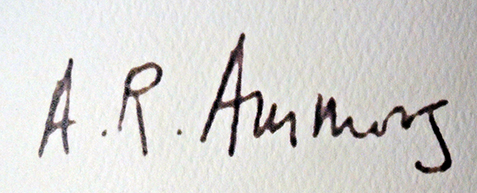

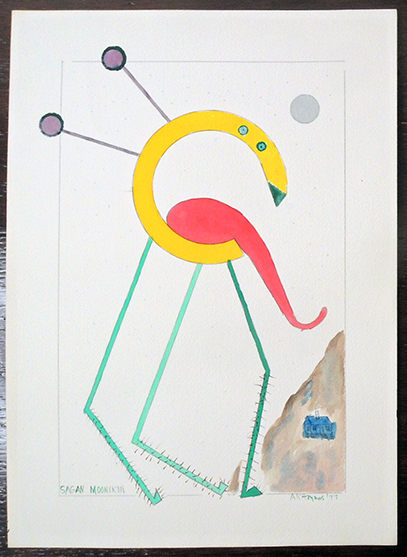

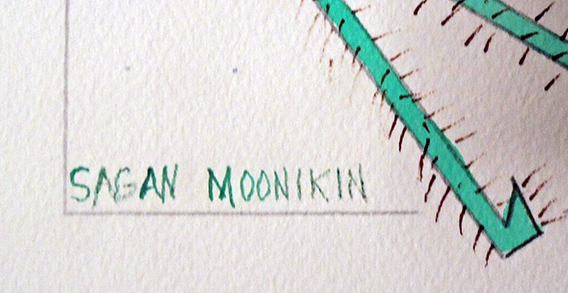

A.R. Ammons (1926-2001), Sagan Moonikin, ca. 1977. Signed by the artist. Graphic Arts Collection 2020- in process.

A.R. Ammons (1926-2001), Sagan Moonikin, ca. 1977. Signed by the artist. Graphic Arts Collection 2020- in process.

Ammons’ friend Emily Wilson noted, “This is one of a few pictures that Ammons titled: Sagan Moonikin. It was made in a period in which Carl Sagan (1934-1996) had joined the Cornell faculty and was very much in the news of the scientific community. Ammons includes in this modernist watercolor the image of a small farmhouse, which he uses in a number of pictures as a reference to his North Carolina home [not Sagan’s], but he sets it in the granite landscape of Ithaca. Sagan moved to his house on the gorge after Ammons had made this picture and that requires more discussion and research.”

Ammons’ friend Emily Wilson noted, “This is one of a few pictures that Ammons titled: Sagan Moonikin. It was made in a period in which Carl Sagan (1934-1996) had joined the Cornell faculty and was very much in the news of the scientific community. Ammons includes in this modernist watercolor the image of a small farmhouse, which he uses in a number of pictures as a reference to his North Carolina home [not Sagan’s], but he sets it in the granite landscape of Ithaca. Sagan moved to his house on the gorge after Ammons had made this picture and that requires more discussion and research.”

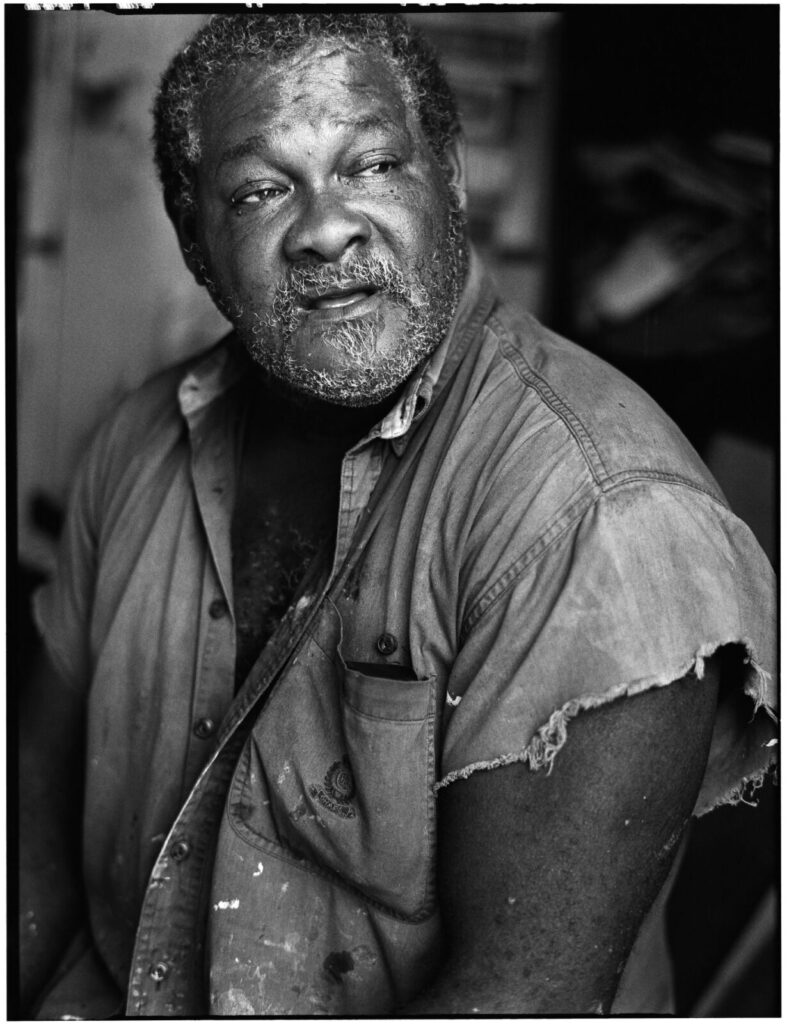

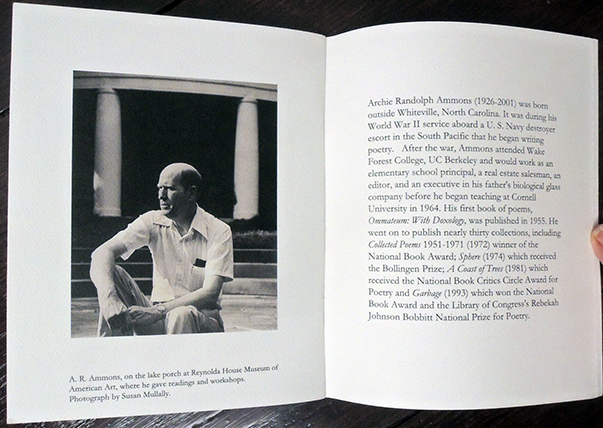

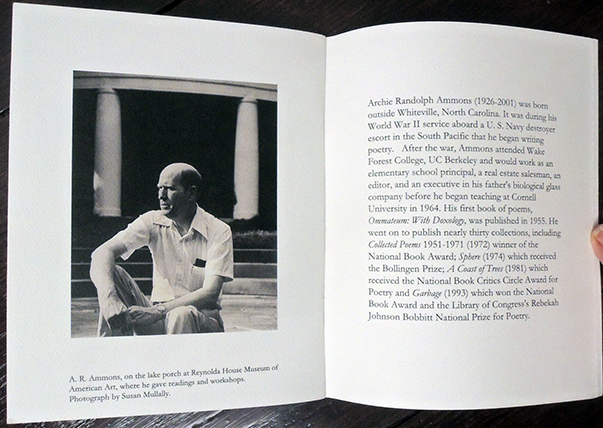

A.R. “Archie” Ammons (1926–2001) was among the first recipients of the MacArthur Fellows Program, unofficially known as the “Genius Grant,” when it was established in 1981. The poet, who taught at Cornell University from 1964 to 1998, received many awards for his writing, among them two National Books Awards, a National Book Critics Circle Award, the Library of Congress’s Rebekah Johnson Bobbitt National Prize for Poetry, and the Bollingen Prize for Poetry. Less known or celebrated were Ammons visual arts, including the six watercolors recently acquired by Princeton’s Graphic Arts Collection.

Our continuing thanks to Susan Stewart, Avalon Foundation University Professor in the Humanities and Professor of English at Princeton University and to Emily Herring Wilson, longtime friend of Ammons, for their help with this acquisition. In her remembrance of the poet, Wilson noted the year he took up painting with a vengeance:

“Moving back into their house on Hanshaw Road, Archie set up a table in the upstairs bedroom looking out into the backyard he loved so much and had written about so often, and he began painting water-colors. In 1977 he was painting as many as six or eight hours a day. In 1981, he described the process in one of the most revealing statements he ever made about the sources of his creativity:

‘The is a poetics of tears, of smiles, of ecstasy (sensual joy and the harsh inspirations of the religious heights): there is a poetics of quietude and deep study, a poetics of fear—and a poetics of anger. During Christmas vacation in 1976, I got the notion which I had had passingly but often before, to try watercolors. I’m sure I was attracted to the possibility of bringing together in one visual consideration the arbitrariness of pure coincidence with the necessity of the essential, the moving form the free, as the work of art begins, through the decisions of pattern and possibility, and into and through the demands of the necessary, the unavoidable, the inevitable. This “change” is in another from the oldest of journeys, that from exile to community.

Having had dozens of tries at real pictures, I began to feel what events on the paper “meant”—that is, I began to learn the joining of what happened on the paper to its emotional counterpart, the feelings generated and expressed by the events. I discovered that I was stirred by the thin, loud, and bright, the utterly blatant effect like a smack in the face, the anger felt, expressed, reacted to. And then I thought that not a very nice thing to be into. But I was angry, sizzlingly angry for whatever reasons, and I found myself, when I could endure the emotions at all, released by letting the anger go and become the splatters and the sheer control of the paint. And then I thought that since we must after all at times be angry, how fortunate we are that art allows us to transform blistering feelings int the brilliance, the sweep and curve, the dash and astonishment (along with the cool definition, judgment, and knowledge) of still completed things.’” –Emily Herring Wilson, When I go back to my home country: a remembrance of Archie Ammons (Fountain, NC: R.A. Fountain, 2019).

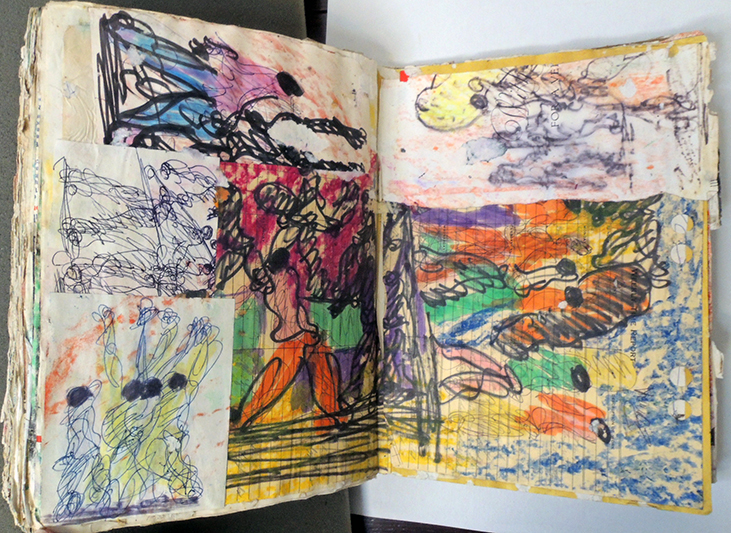

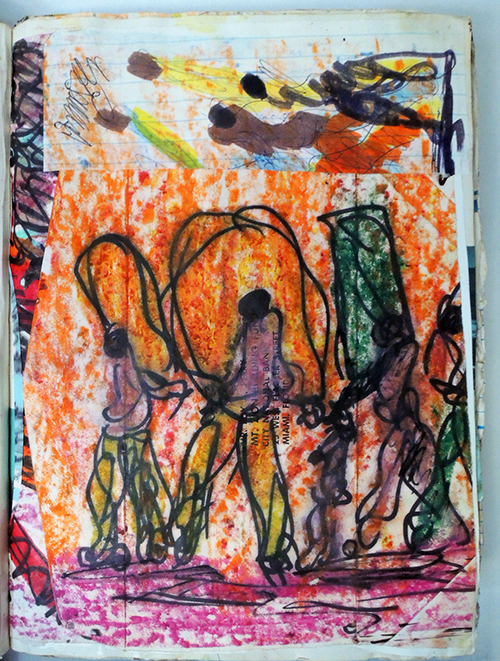

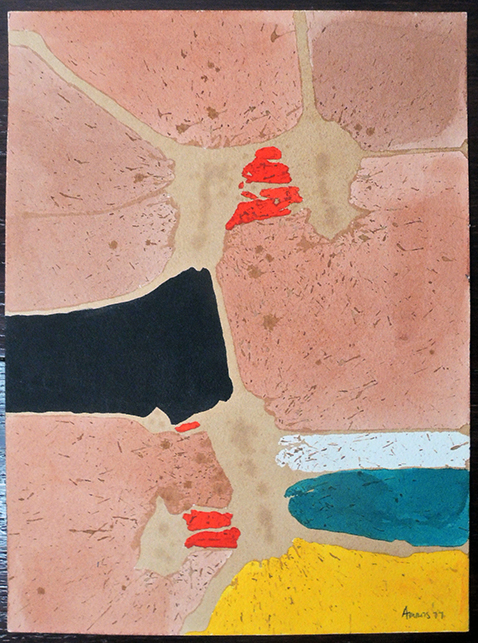

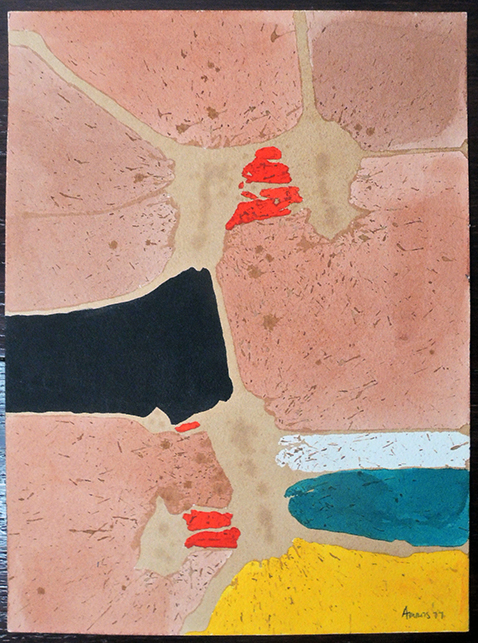

A.R. Ammons, Untitled [Abstraction in sections with pink, red, green, and yellow], ca. 1977. 9 x 12 inches. Signed by Ammons. Graphic Arts Collection 2020- in process.

A.R. Ammons, Untitled [Abstraction in sections with pink, red, green, and yellow], ca. 1977. 9 x 12 inches. Signed by Ammons. Graphic Arts Collection 2020- in process.

Note from Wilson “I love this. Because it seems to me to be the North Carolina landscape we have near black lakes in eastern NC and lots of red/pink clay used by potters. Also sandy coasts and sunshine and lots of creeks. For me he has his sizzling anger under control with the beautiful reds.”

See also: Literary Vision. November 1988, A.R. Ammons, John Ashbery, William Blake, William Burroughs, E.E. Cummings, Robert Duncan, Allen Ginsberg, Brion Gysin, D.H. Lawrence, Henri Michaux, Henry Miller, Kenneth Patchen, and Kenneth Rexroth (New York: Jack Tilton Gallery, 1988).

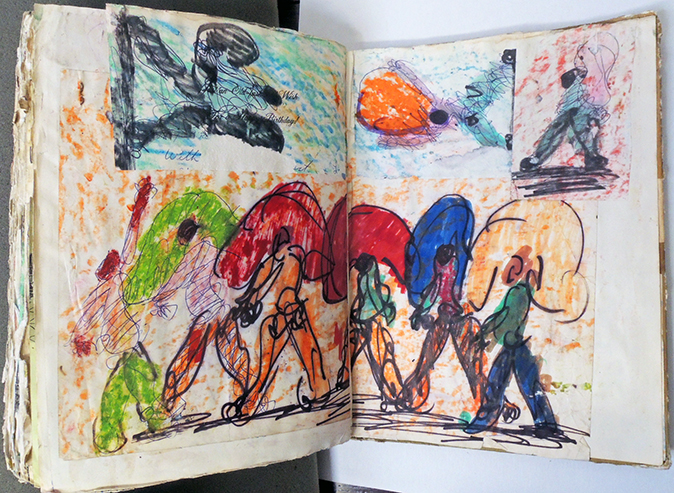

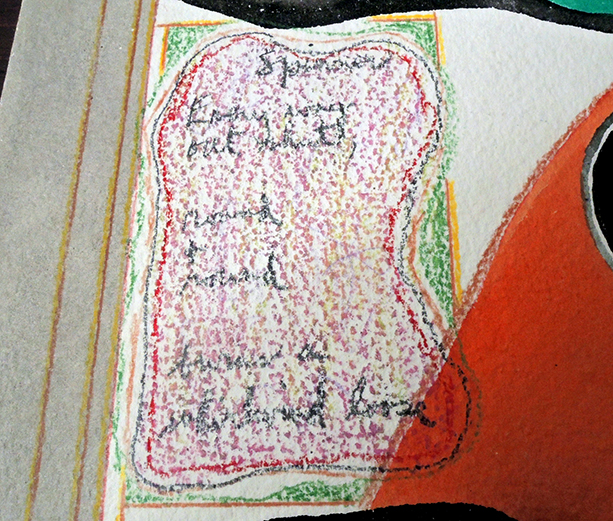

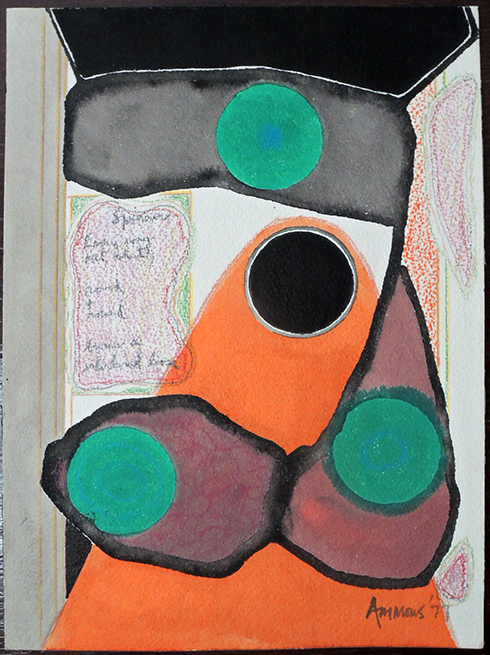

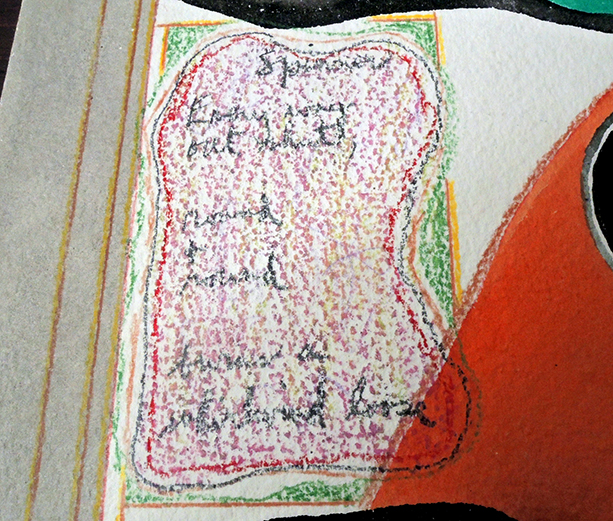

A.R. Ammons, Untitled [Abstraction with verse], 1977. Signed and dated by Ammons. Graphic Arts Collection 2020- in process.

A.R. Ammons, Untitled [Abstraction with verse], 1977. Signed and dated by Ammons. Graphic Arts Collection 2020- in process.

“Over a forty-five year span, A. R. Ammons gained readers, recognition, financial reward, and international acclaim for his verbal creations, not his visual ones. Although longtime subscribers to EPOCH may re member that one of his watercolors graced the 1986–87 cover of the magazine (35:3), most readers of Ammons’s twenty-five poetry collections remain unaware that he also painted more than one thousand watercolors. He did not hide that pursuit; in fact he was proud of his paintings, and from time to time, he promoted them.

From 1977 until 1993, he entered his work in twelve separate exhibits at sites from the Johnson Art Museum at Cornell to the Jack Tilton Gallery in New York City, where four of his paintings appeared in the show “Literary Vision,” along with [others]. He also exhibited his paintings in North Carolina, at the Reynolda Museum of American Art in Winston-Salem and at the University of North Carolina’s Morehead Gallery in Chapel Hill. More recently, in October 2002, The Charlotte and Philip Hanes Art Gallery at Wake Forest University, Ammons’s alma mater, presented an exhibit of fifty of the poet’s paintings; watercolors from that show subsequently appeared on the March and August 2003 covers of Poetry.” — Elizabeth M. Mills, “An Image for Longing,” Epoch 52 no.3 (2003).

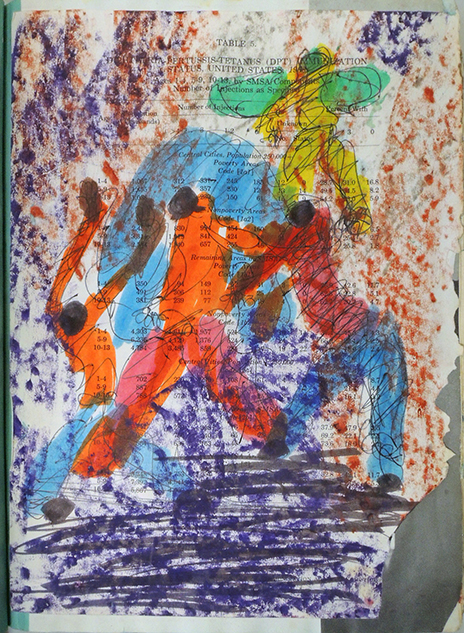

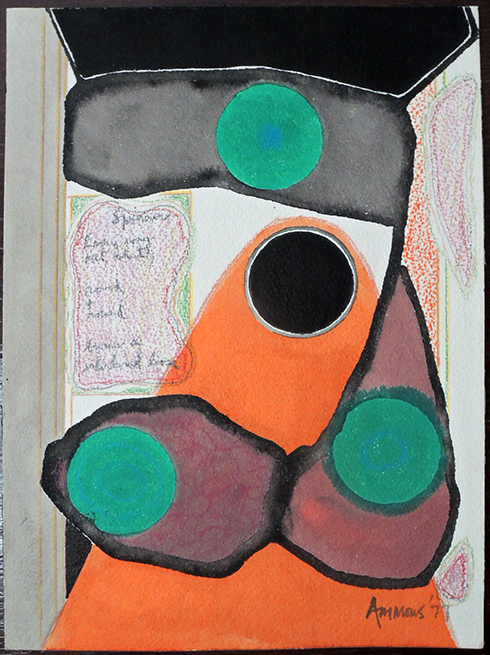

A.R. Ammons, Untitled [Self-portrait, abstract], 1977. Signed and dated by Ammons. Graphic Arts Collection 2020- in process.

A.R. Ammons, Untitled [Self-portrait, abstract], 1977. Signed and dated by Ammons. Graphic Arts Collection 2020- in process.

Wilson notes “Ammons painted a number of these faces, which seem to be self-portraits but require more study to have a clearer understanding.”

See also: Jonathan Dembo, A.R. Ammons’s poetry and art : a documentary exhibit : exhibit catalog (Greenville, N.C. : J.Y. Joyner Library, East Carolina University, 2008).

and

Donald Friedman and John Wronoski, The writer’s brush : an exhibition of artwork by writers (New York, NY : Anita Shapolsky Art Foundation, 2014)

A.R. Ammons, Untitled [Abstraction with nature in blue, red, and brown], 1977. Signed by Ammons. Graphic Arts Collection 2020- in process.

A.R. Ammons, Untitled [Abstraction with nature in blue, red, and brown], 1977. Signed by Ammons. Graphic Arts Collection 2020- in process.

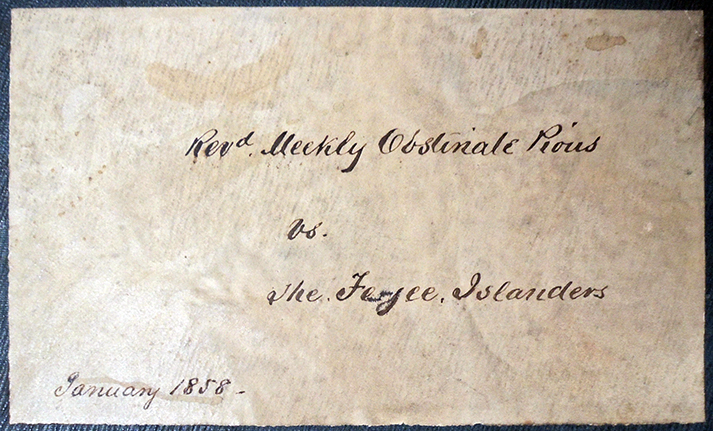

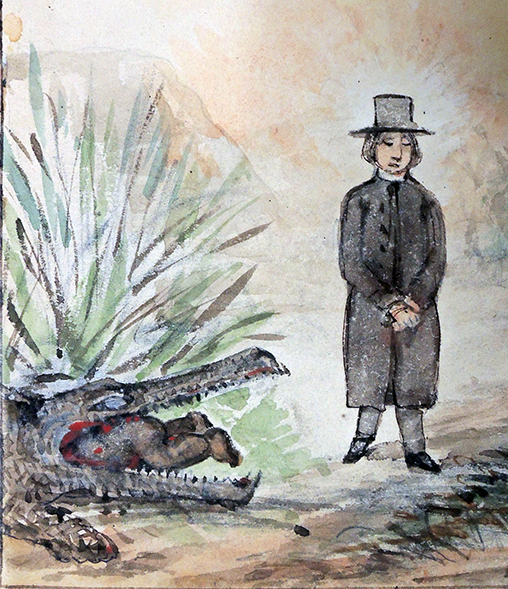

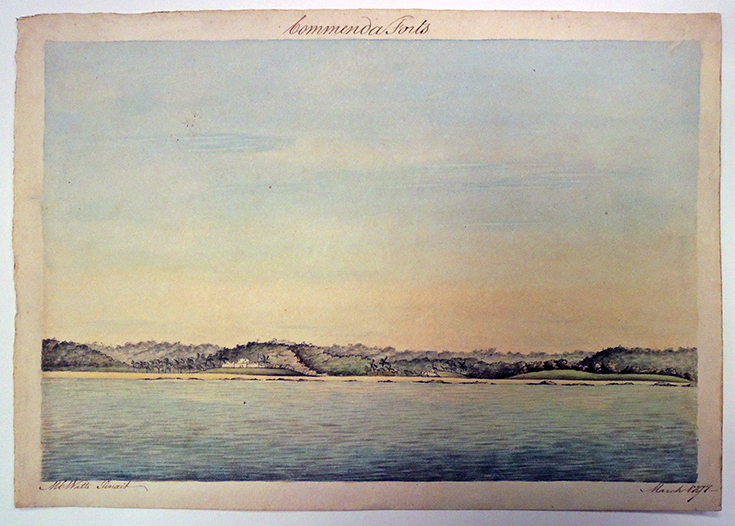

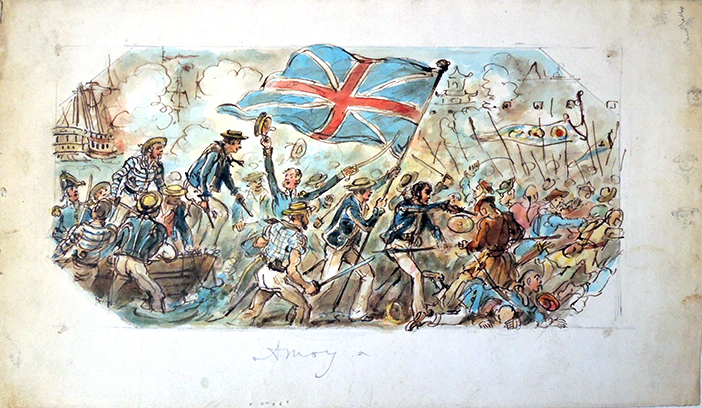

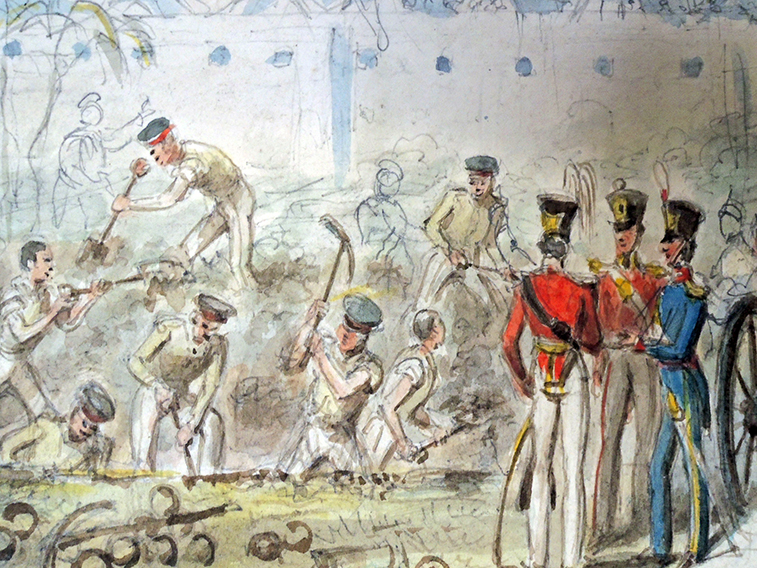

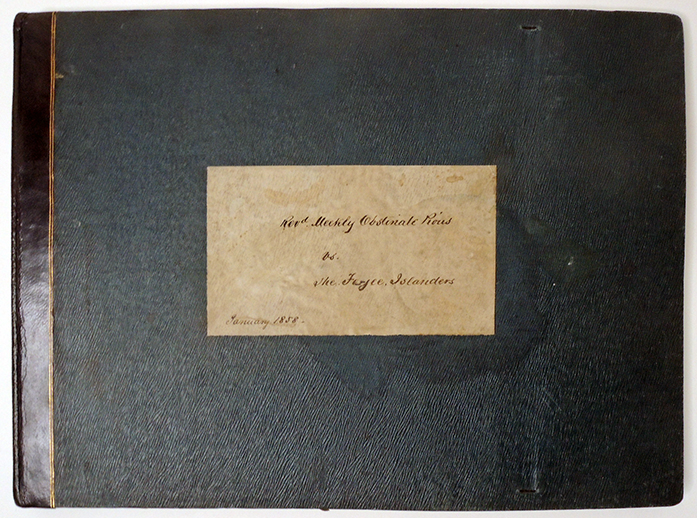

Unidentified artist, Rev’d Meekly Obstinate Pious vs. the Fegee Islanders. January 1858 [England, mid-19th century]. Fourteen watercolors in oblong album. Graphic Arts Collection GAX 2021- in process

Unidentified artist, Rev’d Meekly Obstinate Pious vs. the Fegee Islanders. January 1858 [England, mid-19th century]. Fourteen watercolors in oblong album. Graphic Arts Collection GAX 2021- in process