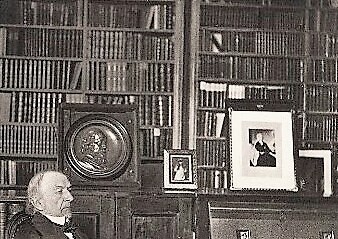

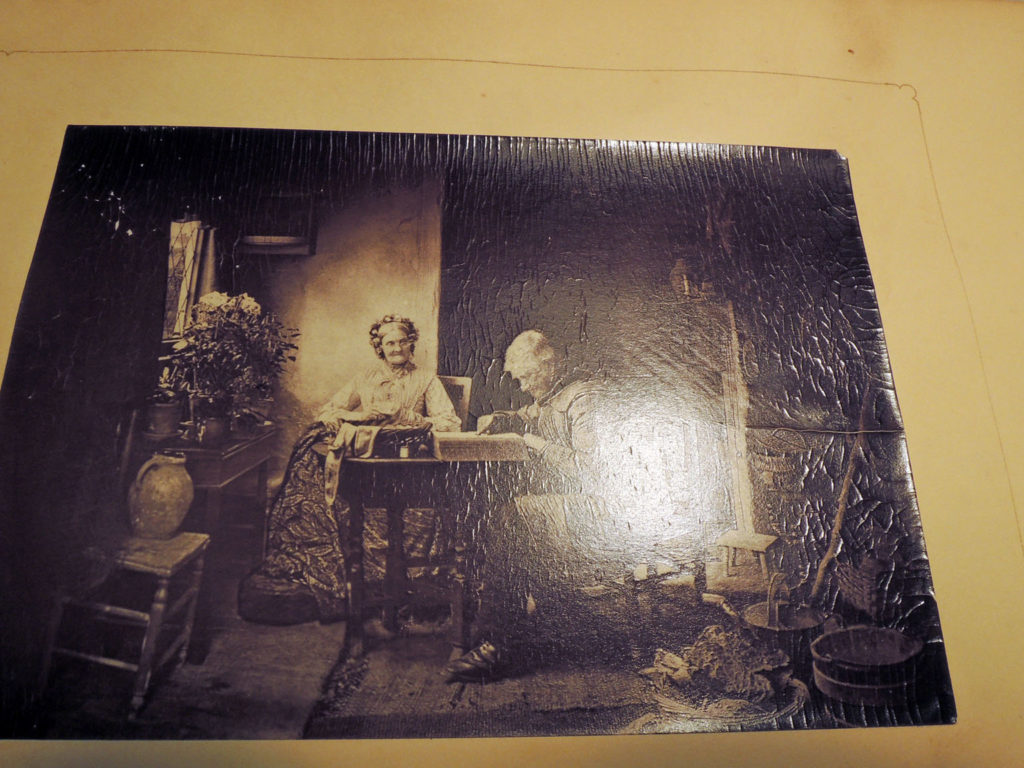

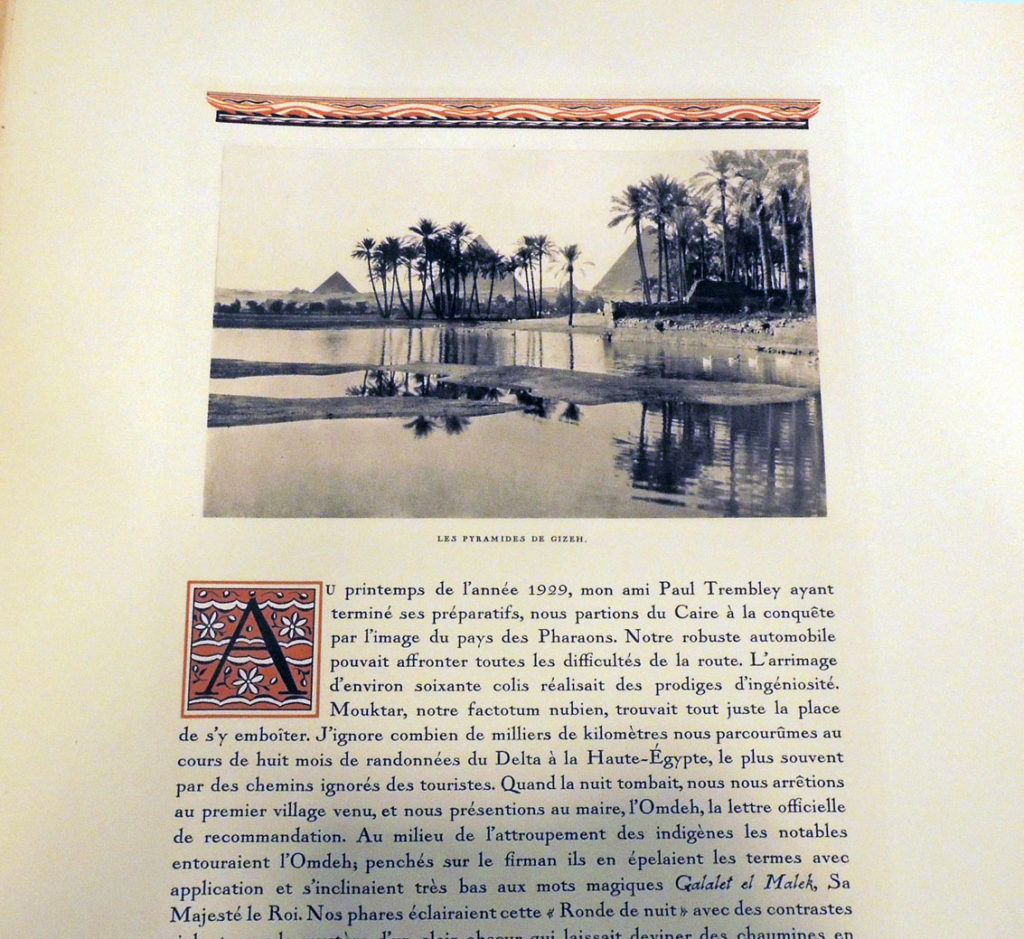

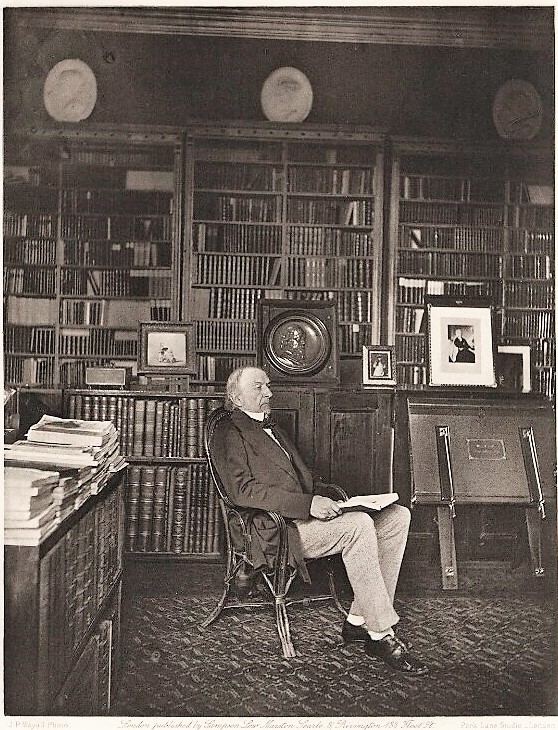

Joseph Parkin Mayall (1839-1906), William Ewart Gladstone, 1883. Photogravure. Published in Artists at Home, edited by Frederick George Stephens (London: Sampson Low, Marston, Searle and Rivington, 1884). Graphic Arts Collection GAX Oversize 2007-0028F

Joe Mayall was forty-three when he left work in the family business established by his father, daguerreotypist John Jabez Edwin Mayall (1813–1901), and opened his own photography studio at 548 Oxford Street, near the Marble Arch in 1882.

The following year, the firm Sampson Low, Marston, Searle, and Rivington proposed a series of luxury prints depicting prominent artists of the day in their homes, surrounded by their work. Equal weight was to be given to the men and the interiors, featuring “pictures, sculptures, and other objects of art which characterise those places,” according to the prospectus. Since Sampson Low had already retired from the firm, credit for the project might go to Edward Marston (1825-1914), who continued to publish luxury volumes.

Art critic George Stephens (1828-1907) was hired to write the biographies and Mayall secured the commission to make the portraits. Forty-eight men were photographed but only twenty-five appear in the final publication, issued monthly from March to August 1884. Each part cost five shillings, with the final bound volume priced at 42 shillings (£2.40). Mayall’s assistant Frank Dudman (1855-1918) filed his own name to the copyright on many of the negatives.

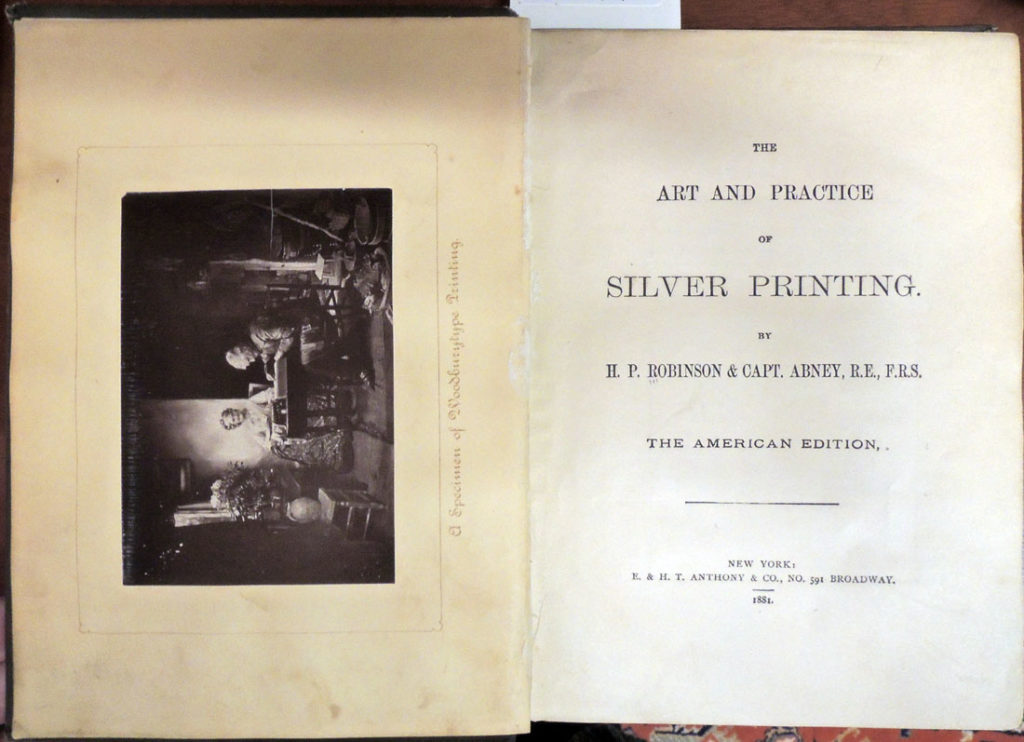

From the beginning, the portraits were planned as photogravures, advertised in the prospectus as the “entirely new and unquestionably permanent process of photoengraving.” When the book was later reviewed, it was called a “marvels of skill and workmanship.” Thanks to the exhibition at Emery College, we learn that “the first set of photogravures was printed in Paris, but something went awry with one of the plates, and although the March 1st publication date had been confidently announced for weeks, that initial installment was embarrassingly delayed.” Chiswick Press printed the rest of the volume but there is no information on the engraver who made and printed of the plates.

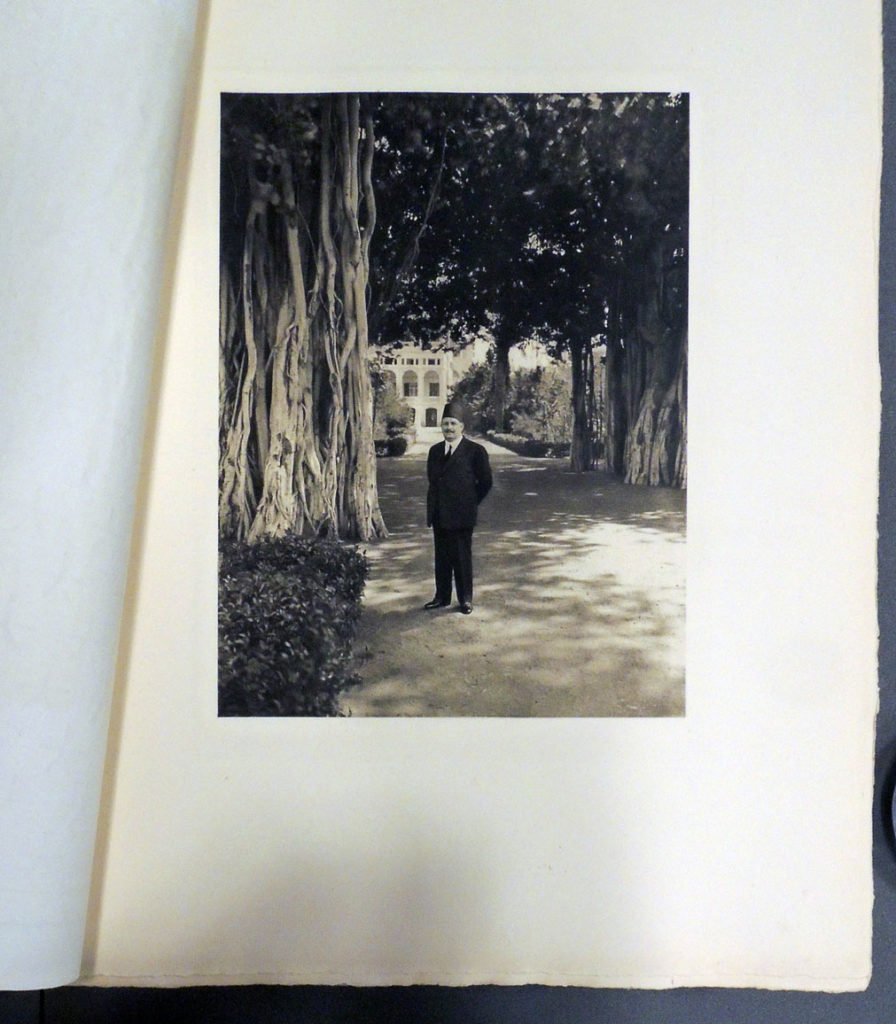

The book is dedicated to Frederic Leighton (1830-1896) [below] but he was pushed aside at the last minute to feature Prime Minister William Ewart Gladstone (1809-1898) as the frontispiece. Although not a painter, he was an Honorary Professor of Ancient History at the Royal Academy. Photographed in his library at Hawarden Castle, Gladstone later became the subject of an article Mayall published describing the two days spent photographing; “Mr. Gladstone at Home. The Whole-Hearted Homage of a Hero-Worshipper,” Pall Mall Gazette no. 7600 (July 27, 1889).

“I packed up my apparatus and started off with my assistant on January 15, 1883, by the 5:15 A.M. train, from Euston. We arrived at Broughton Hall in due course, distant about two miles from Hawarden Castle, which was visible from the railway station. We drove over in a trap. The day was dull and unpromising for photography.”

“Now came the technical and other difficulties to be surmounted in taking a photograph of Mr. Gladstone in his sitting-room [known as the] ‘Temple of Peace.’ . . . Mrs. Gladstone suggested to me that if I found the books in the way they could be removed. I said, ‘No! madam, don’t touch them. I am somewhat of a bookworm myself, and am jealous of any one disturbing my books. I will bring that much-treasured bookcase in view when I photograph Mr. Gladstone,’ which I afterwards did.”

“…All the preparations being made and ready, the camera in site, double slides charged, and a good solid head-rest placed behind the chair, Mr. Gladstone was seated and I exposed the plate 120 seconds. Mrs. Gladstone and her son, who were in the library at the time, thought that I had exposed the plate five minutes, the time seemed so long. I said no, I had counted 120 long seconds, so Mr. Gladstone very good naturedly said, “Photographic seconds,” which I explained must be lengthened out if possible, as every photographer dreads under- exposure.”

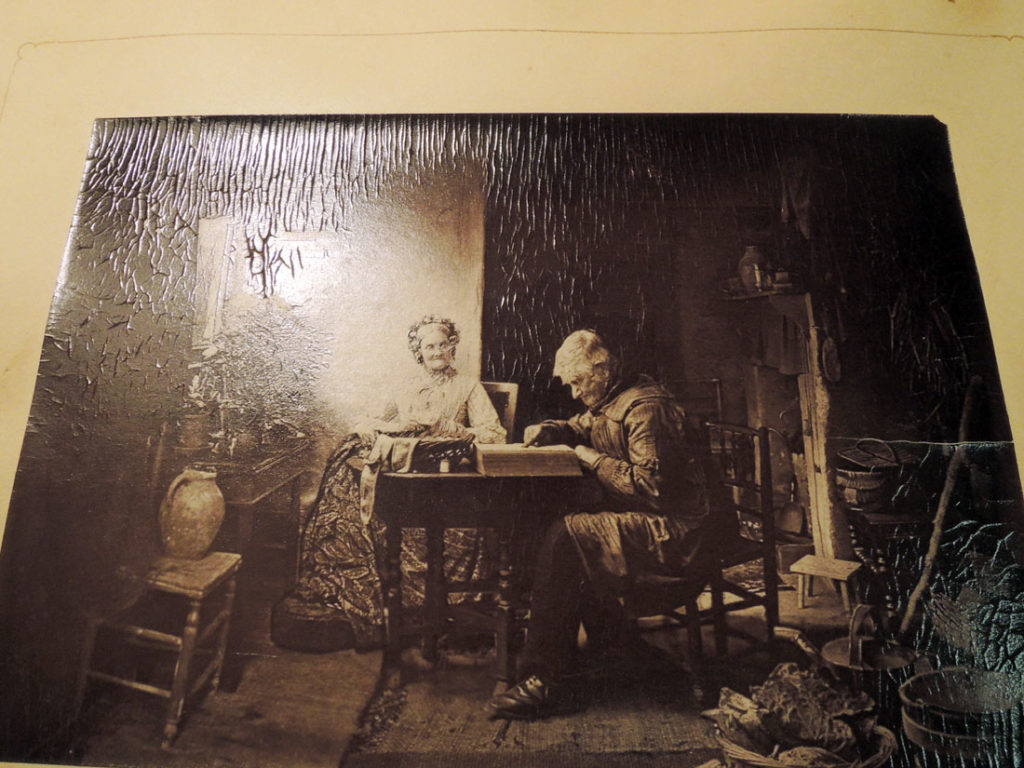

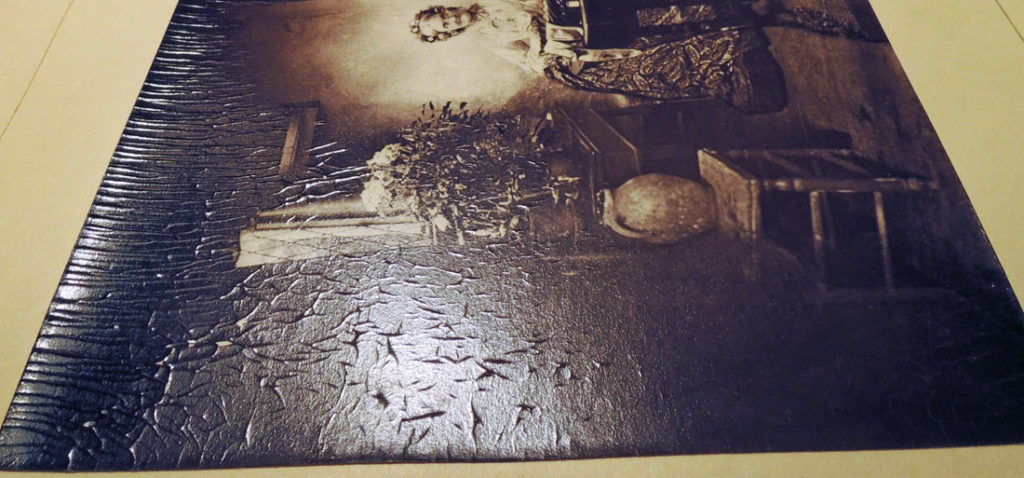

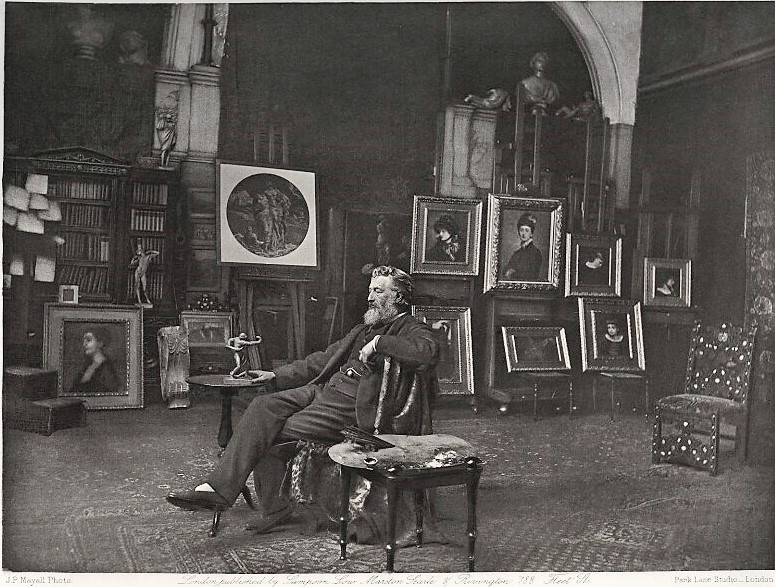

Joseph Parkin Mayall (1839-1906), Frederic Leighton, Baron Leighton, ca. 1883. Photogravure. Published in Artists at Home, edited by Frederick George Stephens (London: Sampson Low, Marston, Searle and Rivington, 1884). Graphic Arts Collection GAX Oversize 2007-0028F

Joseph Parkin Mayall (1839-1906), Frederic Leighton, Baron Leighton, ca. 1883. Photogravure. Published in Artists at Home, edited by Frederick George Stephens (London: Sampson Low, Marston, Searle and Rivington, 1884). Graphic Arts Collection GAX Oversize 2007-0028F