William M. Notman (1857-1913), Helen Keller and Miss Sullivan, 1897. Gelatin silver print. Graphic Arts Collection GA 2009.00892. Gift of Laurence Hutton.

William M. Notman (1857-1913), Helen Keller and Miss Sullivan, 1897. Gelatin silver print. Graphic Arts Collection GA 2009.00892. Gift of Laurence Hutton.

During the two years I spent in New York I had many opportunities to talk with distinguished people whose names I had often heard, but whom I had never expected to meet. Most of them I met first in the house of my good friend, Mr. Laurence Hutton. It was a great privilege to visit him and dear Mrs. Hutton in their lovely home, and see their library and read the beautiful sentiments and bright thoughts gifted friends had written for them. It has been truly said that Mr. Hutton has the faculty of bringing out in every one the best thoughts and kindest sentiments. One does not need to read “A Boy I Knew” to understand him–the most generous, sweet-natured boy I ever knew, a good friend in all sorts of weather, who traces the footprints of love in the life of dogs as well as in that of his fellowmen.

Mrs. Hutton is a true and tried friend. Much that I hold sweetest, much that I hold most precious, I owe to her. She has oftenest advised and helped me in my progress through college. When I find my work particularly difficult and discouraging, she writes me letters that make me feel glad and brave; for she is one of those from whom we learn that one painful duty fulfilled makes the next plainer and easier.

Mr. Hutton introduced me to many of his literary friends, greatest of whom are Mr. William Dean Howells and Mark Twain. –Helen Keller, The Story of My Life, chapter 23

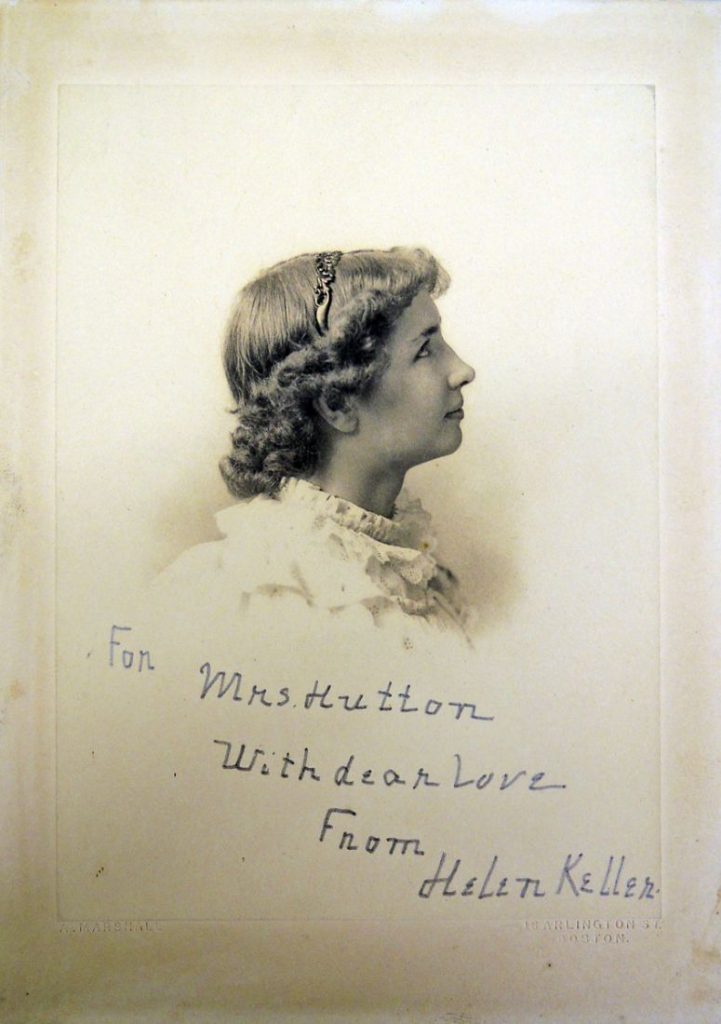

Augustus Marshall (died 1916), Helen Keller, no date. Gelatin silver print. Graphic Arts Collection GA 2009.00891. Gift of Laurence Hutton. Blind stamp on mount: “A. Marshall 16 Arlington St. Boston”. Dedication in pencil: “For Mrs. Hutton, With dear love, From, Helen Keller.”

Augustus Marshall (died 1916), Helen Keller, no date. Gelatin silver print. Graphic Arts Collection GA 2009.00891. Gift of Laurence Hutton. Blind stamp on mount: “A. Marshall 16 Arlington St. Boston”. Dedication in pencil: “For Mrs. Hutton, With dear love, From, Helen Keller.”

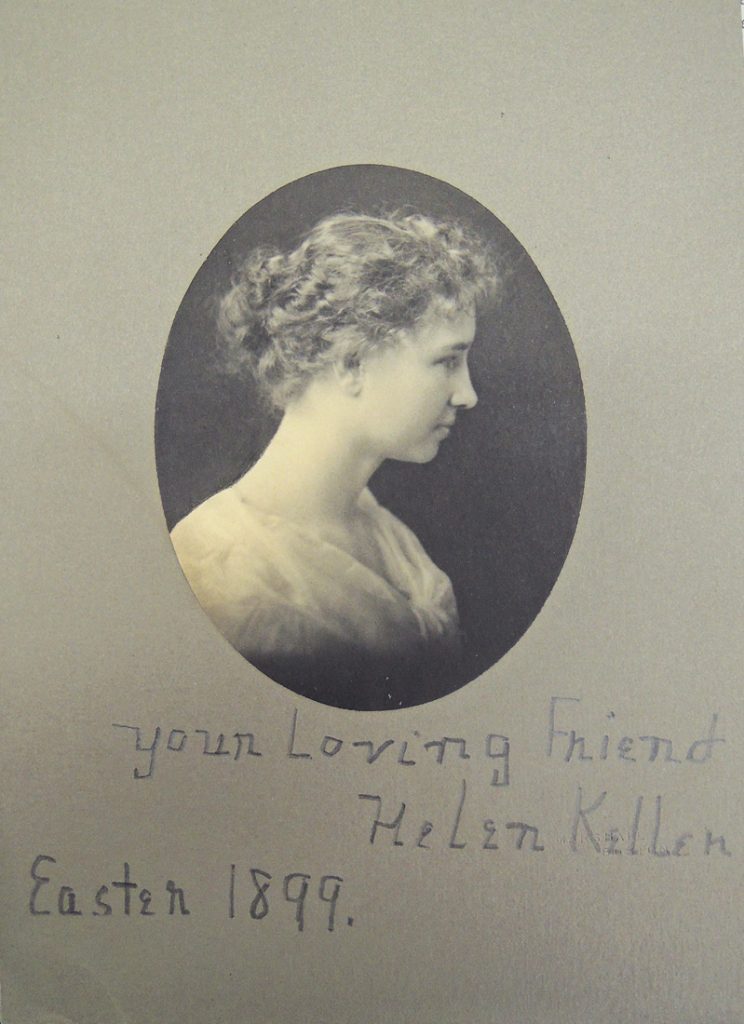

Augustus Marshall (died 1916), Helen Keller, no date [ca. 1899]. Gelatin silver print. Graphic Arts Collection GA 2009.00890. Gift of Laurence Hutton. Dedication in pencil: “Your loving friend, Helen Keller, Easter 1899.”

Augustus Marshall (died 1916), Helen Keller, no date [ca. 1899]. Gelatin silver print. Graphic Arts Collection GA 2009.00890. Gift of Laurence Hutton. Dedication in pencil: “Your loving friend, Helen Keller, Easter 1899.”

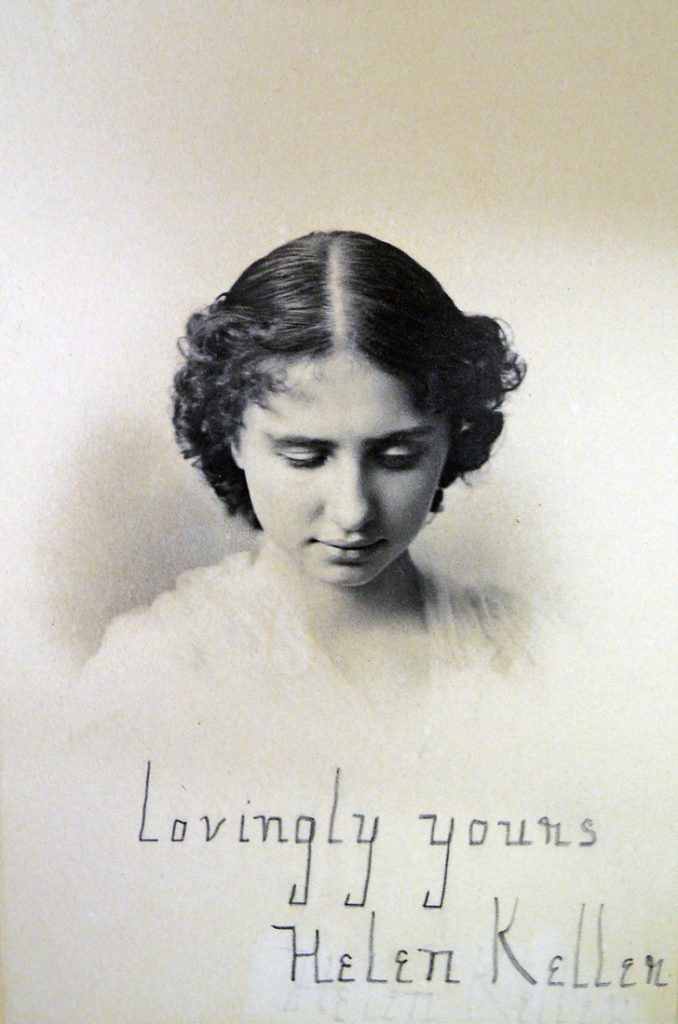

Benjamin J. Falk (1853-1925), Helen Keller, no date. Platinum print. Graphic Arts Collection GA 2009.00831. Gift of Laurence Hutton. Dedication in pencil: “Lovingly yours, Helen Keller.” Signed in imprint: “Print in Platinum – Falk, N.Y.”

Benjamin J. Falk (1853-1925), Helen Keller, no date. Platinum print. Graphic Arts Collection GA 2009.00831. Gift of Laurence Hutton. Dedication in pencil: “Lovingly yours, Helen Keller.” Signed in imprint: “Print in Platinum – Falk, N.Y.”

Benjamin J. Falk (1853-1925), Helen Keller and Anne Sullivan, [no date]. Platinum print. Graphic Arts Collection GA 2009.00832. Gift of Laurence Hutton. Signed by sitter in pencil: “Helen and Teacher.” Signed by sitter in ink: “Annie M. Sullivan.”

Benjamin J. Falk (1853-1925), Helen Keller and Anne Sullivan, [no date]. Platinum print. Graphic Arts Collection GA 2009.00832. Gift of Laurence Hutton. Signed by sitter in pencil: “Helen and Teacher.” Signed by sitter in ink: “Annie M. Sullivan.”

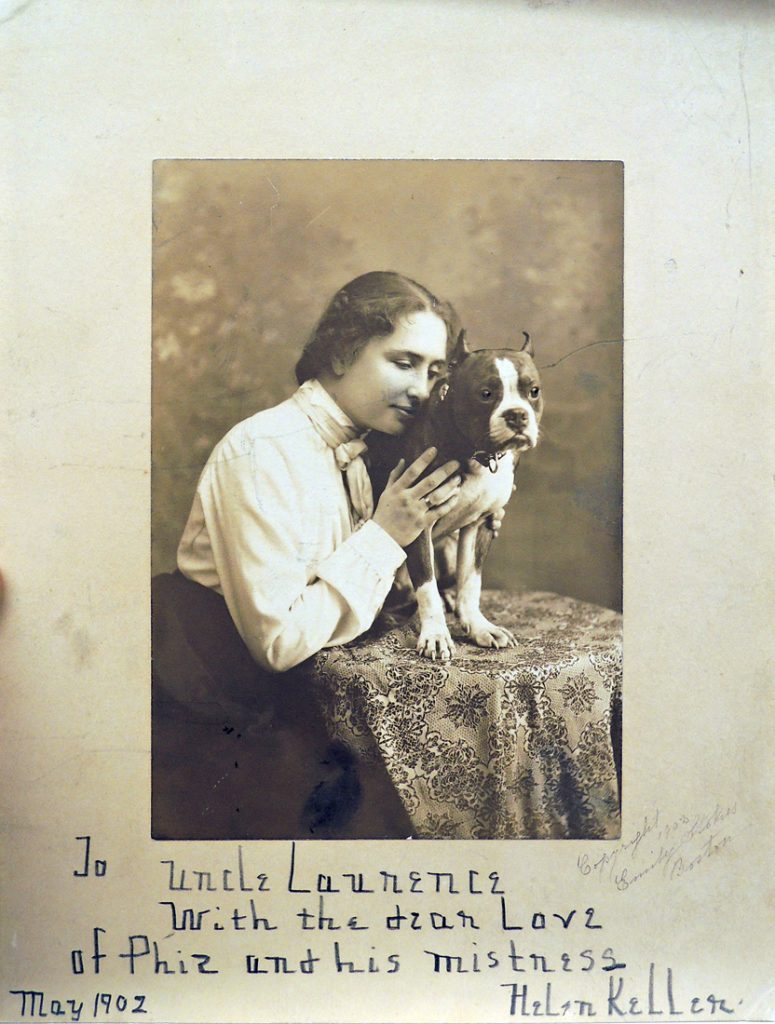

Emily Stokes, Helen Keller with Her Terrier, Phiz, 1902. Albumen silver print. Graphic Arts Collection GA 2010.01663. Gift of Laurence Hutton. Dedication in pencil: “To Uncle Laurence, with the dear love of Phiz and his mistress, May 1902, Helen Keller.”

Emily Stokes, Helen Keller with Her Terrier, Phiz, 1902. Albumen silver print. Graphic Arts Collection GA 2010.01663. Gift of Laurence Hutton. Dedication in pencil: “To Uncle Laurence, with the dear love of Phiz and his mistress, May 1902, Helen Keller.”

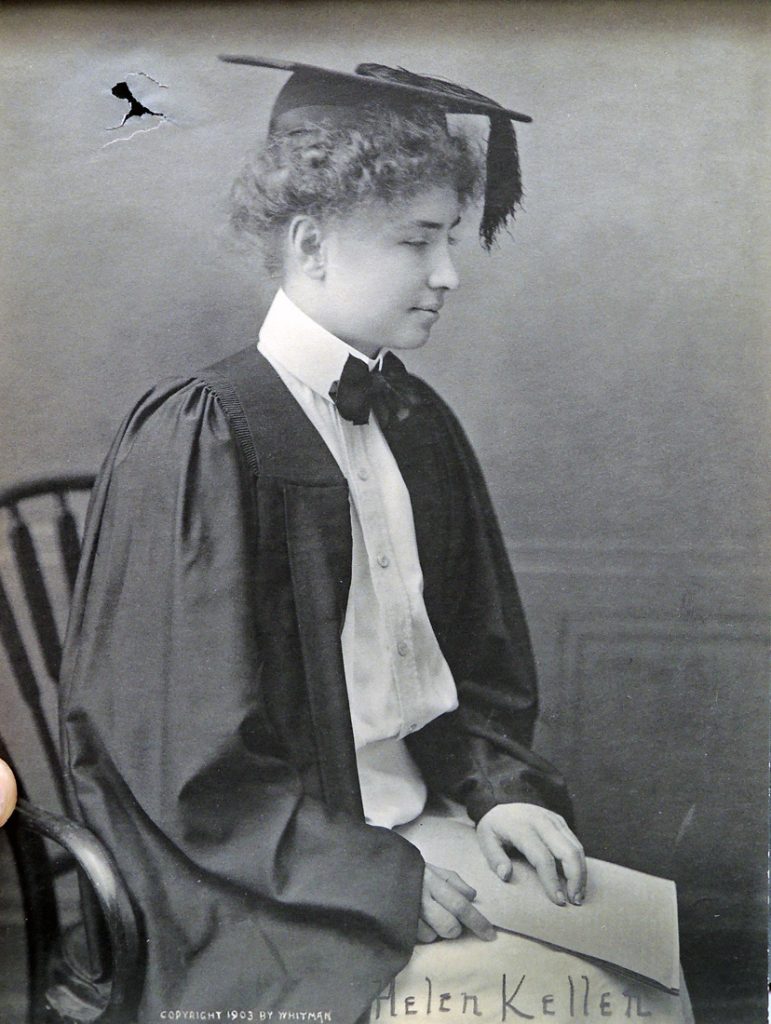

Unidentified artist, Helen Keller in Academic Attire, 1903. Gelatin silver print. Signed in negative: “Copyright 1903 by Whitman” Graphic Arts Collection GA 2010.01794. Gift of Laurence Hutton. Signed in pencil: “Helen Keller.”

Unidentified artist, Helen Keller in Academic Attire, 1903. Gelatin silver print. Signed in negative: “Copyright 1903 by Whitman” Graphic Arts Collection GA 2010.01794. Gift of Laurence Hutton. Signed in pencil: “Helen Keller.”

Unidentified artist, Helen Keller, no date [ca. 1899]. Albumen silver print. Graphic Arts Collection GA 2010.02226. Gift of Laurence Hutton.

Unidentified artist, Helen Keller, no date [ca. 1899]. Albumen silver print. Graphic Arts Collection GA 2010.02226. Gift of Laurence Hutton.