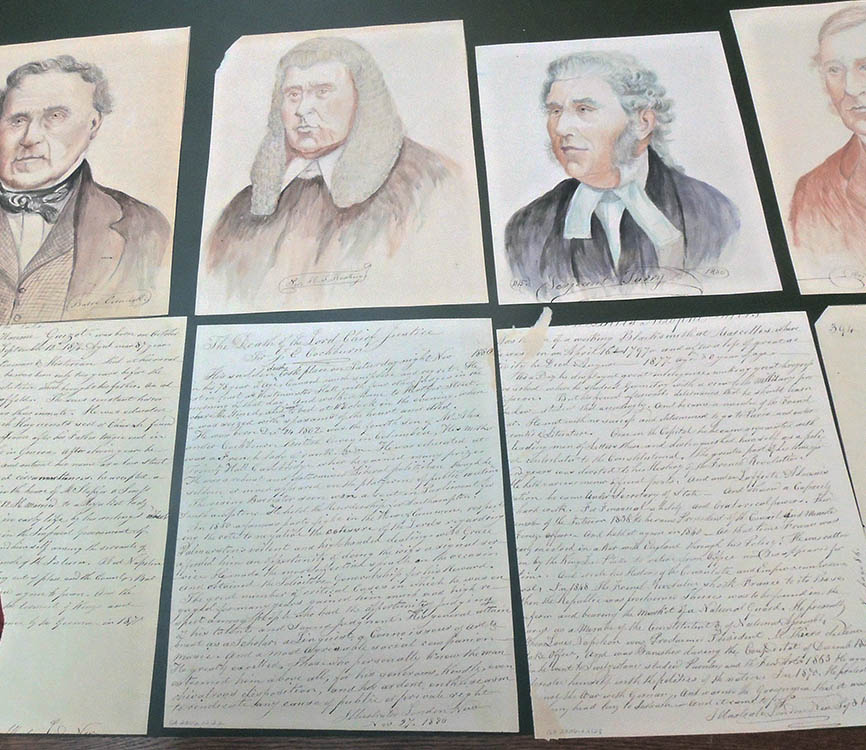

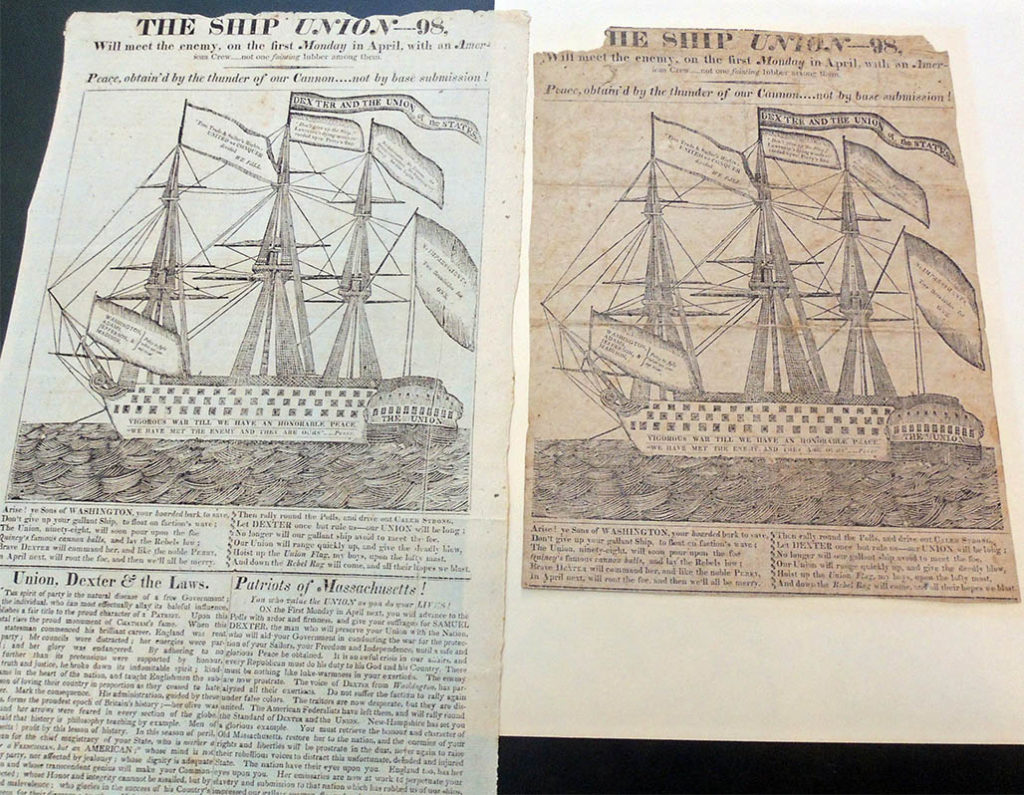

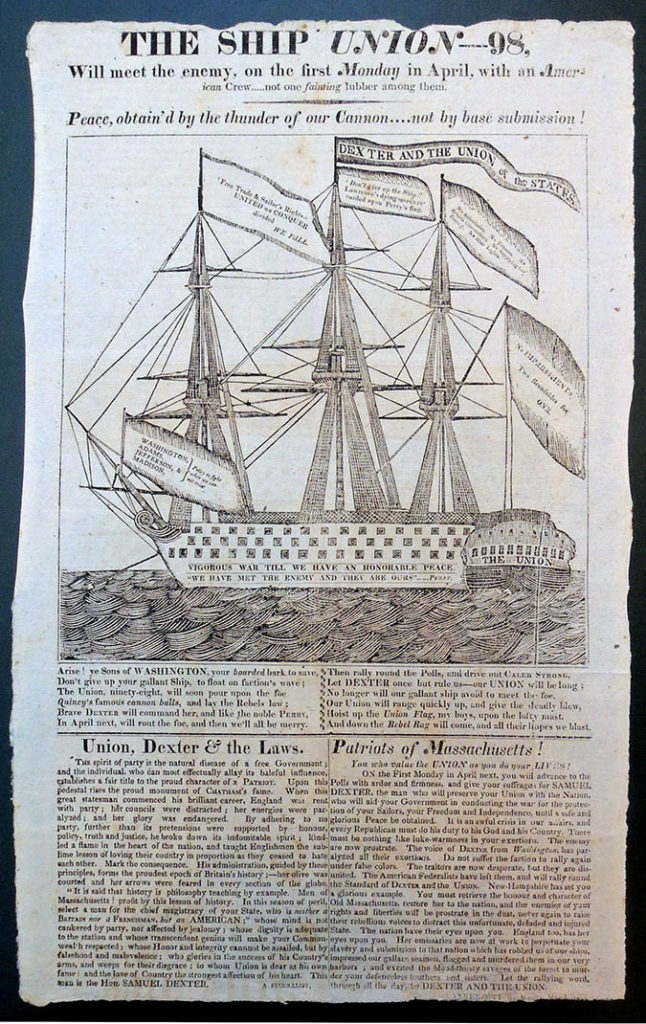

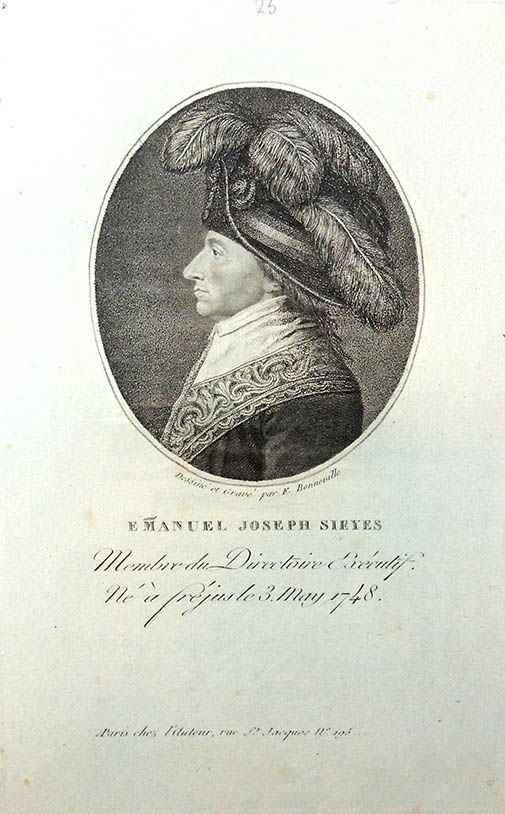

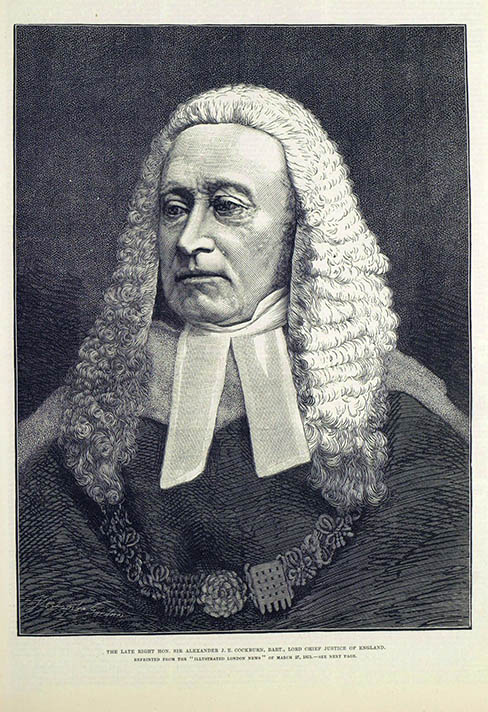

The Graphic Arts Collection has a series of portraits all done in the same unidentified hand. Was this a class assignment to copy 19th-century black and white sources, and then add color? Or were these actually connected to the source?

The Graphic Arts Collection has a series of portraits all done in the same unidentified hand. Was this a class assignment to copy 19th-century black and white sources, and then add color? Or were these actually connected to the source?

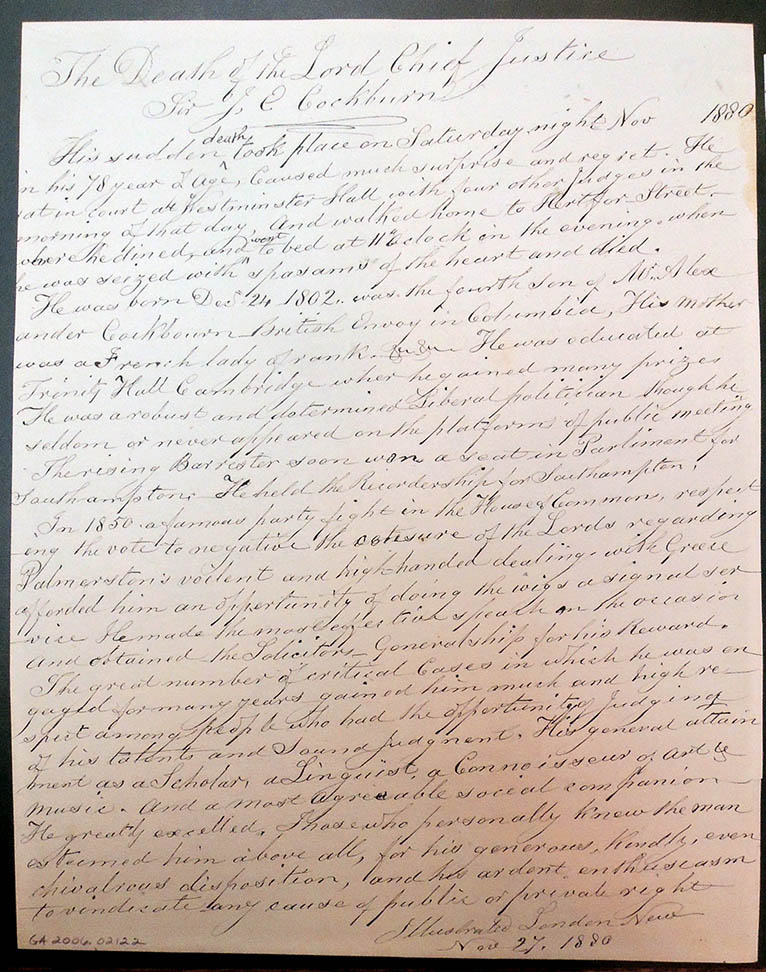

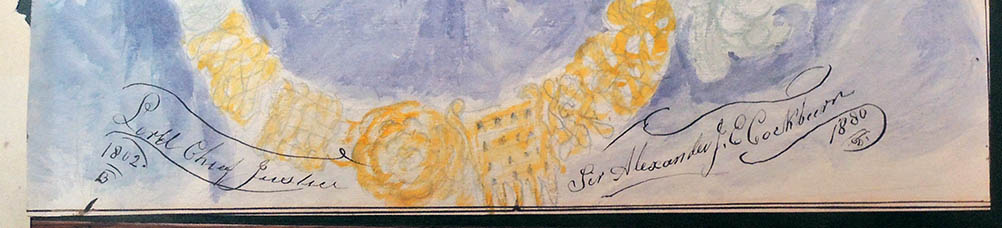

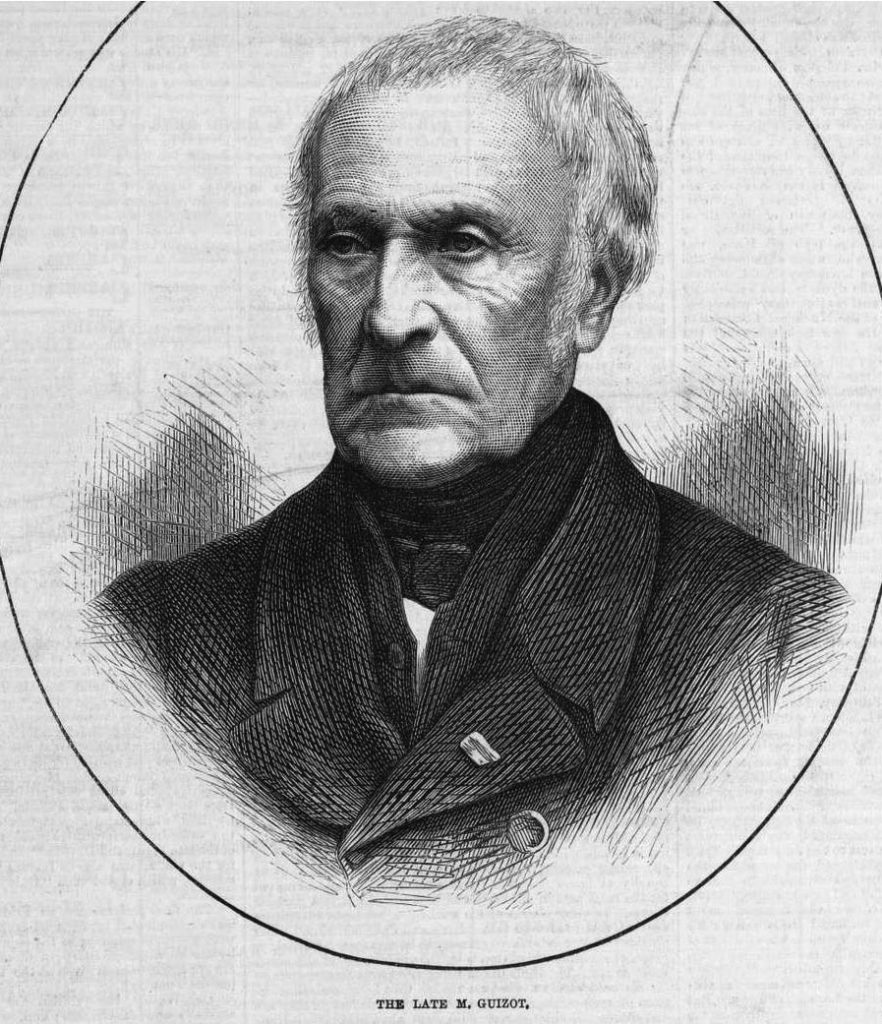

Each portrait has an ink transcription on the back taken from the Illustrated London News obituary for these men: Justice Field; Sir Thomas Henry; M. Thiers, Fitzroy Kelley, Sergeant Parry, Alexander J.E. Cockburn, G.H. Lewes-Litera, and F.P.G. Guizot. Neither the portrait nor the text are exact copies.

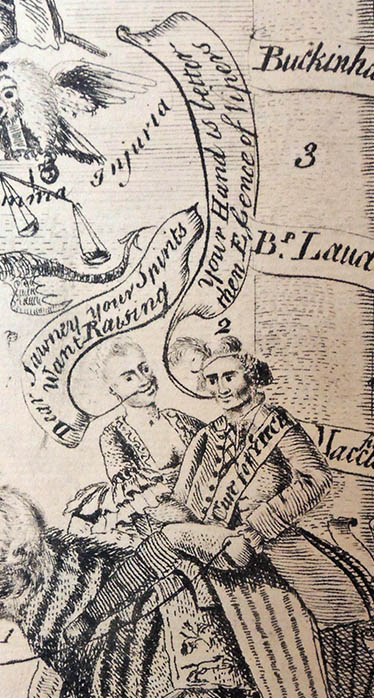

When you go back to the original portrait and put the two faces side-by-side, the amateur style of the watercolor becomes apparent but the numbering on many and elaborate caption seem to indicate a serious project.

Source Citation: “Death of the Lord Chief Justice.” Illustrated London News [London, England] 27 Nov. 1880: 522+. Illustrated London News. Web. 25 June 2019. URL:http://find.galegroup.com/iln/infomark.do?&source=gale&prodId=ILN&userGroupName=prin77918&tabID=T003&docPage=article&docId=HN3100108866&type=multipage&contentSet=LTO&version=1.0

Source Citation: “Death of the Lord Chief Justice.” Illustrated London News [London, England] 27 Nov. 1880: 522+. Illustrated London News. Web. 25 June 2019. URL:http://find.galegroup.com/iln/infomark.do?&source=gale&prodId=ILN&userGroupName=prin77918&tabID=T003&docPage=article&docId=HN3100108866&type=multipage&contentSet=LTO&version=1.0

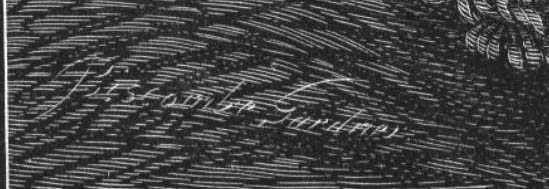

Several of the wood engraved originals (but not all) are signed by Biscombe Gardner, a regular contributor to the Illustrated London News, portraiture a specialty.

Several of the wood engraved originals (but not all) are signed by Biscombe Gardner, a regular contributor to the Illustrated London News, portraiture a specialty.

William Biscombe Gardner (1847–1919) was a British painter and wood-engraver. Working in both watercolour and oils, he exhibited widely in London in the late 19th century at venues such as the Royal Academy and the Grosvenor Gallery.[1] From 1896 he lived at Thirlestane Court. He illustrated a number of books featuring the British landscape (see below), notably Kent, Canterbury, and The Peak Country. He also drew scenes from the Welsh Elan Valley in the 1890s, before it was flooded to form the Elan Valley Reservoirs, which appeared in two books by Grant Allen (see “illustrated Books” below). However, it was as a fine wood-engraver that he was mainly known, providing illustrations (sometimes large) for British magazines of the day such as The Pall Mall Gazette, The Illustrated London News, The English Illustrated Magazine and The Magazine of Art. He was a firm advocate of traditional wood-engraving considering it to be the most versatile in comparison to the more conventional methods of engraving and etching, or more recent methods including “process illustration”–DNB

Source Citation: “This Eminent French Statesman and Historian Died on Saturday Night, at His Rural Mansion of Val Richer, Ner Lisieux, in Normandy.” Illustrated London News [London, England] 19 Sept. 1874: 277+. Illustrated London News. Web. 25 June 2019. URL: http://find.galegroup.com/iln/infomark.do?&source=gale&prodId=ILN&userGroupName=prin77918&tabID=T003&docPage=article&docId=HN3100093116&type=multipage&contentSet=LTO&version=1.0

Source Citation: “This Eminent French Statesman and Historian Died on Saturday Night, at His Rural Mansion of Val Richer, Ner Lisieux, in Normandy.” Illustrated London News [London, England] 19 Sept. 1874: 277+. Illustrated London News. Web. 25 June 2019. URL: http://find.galegroup.com/iln/infomark.do?&source=gale&prodId=ILN&userGroupName=prin77918&tabID=T003&docPage=article&docId=HN3100093116&type=multipage&contentSet=LTO&version=1.0

In the end, it is most likely a copy assignment or personal exercise. Why the watercolors stayed together and came to Princeton is still a mystery.