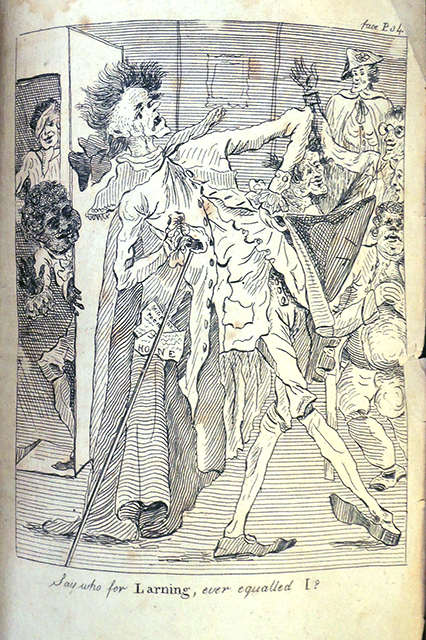

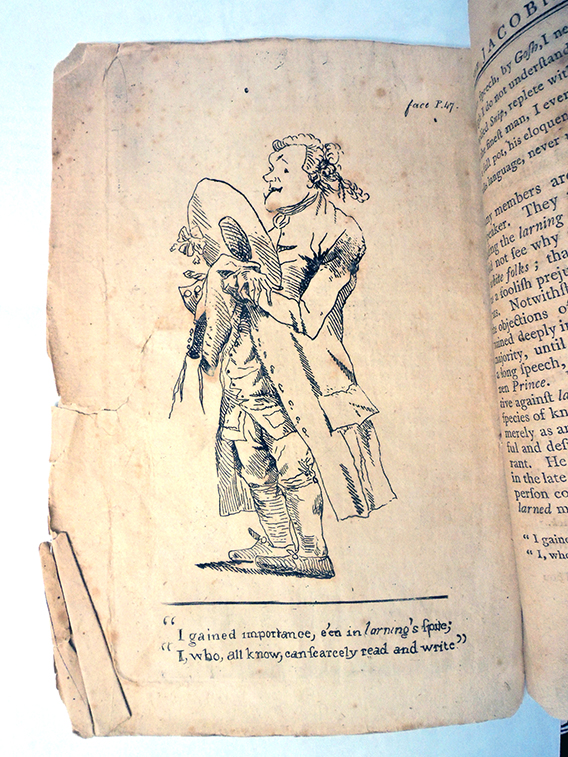

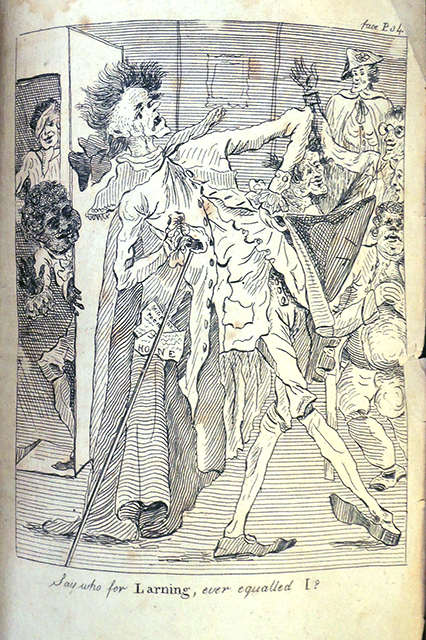

“Say who for Larning, ever equalled I?” Slightly photoshopped

“Say who for Larning, ever equalled I?” Slightly photoshopped

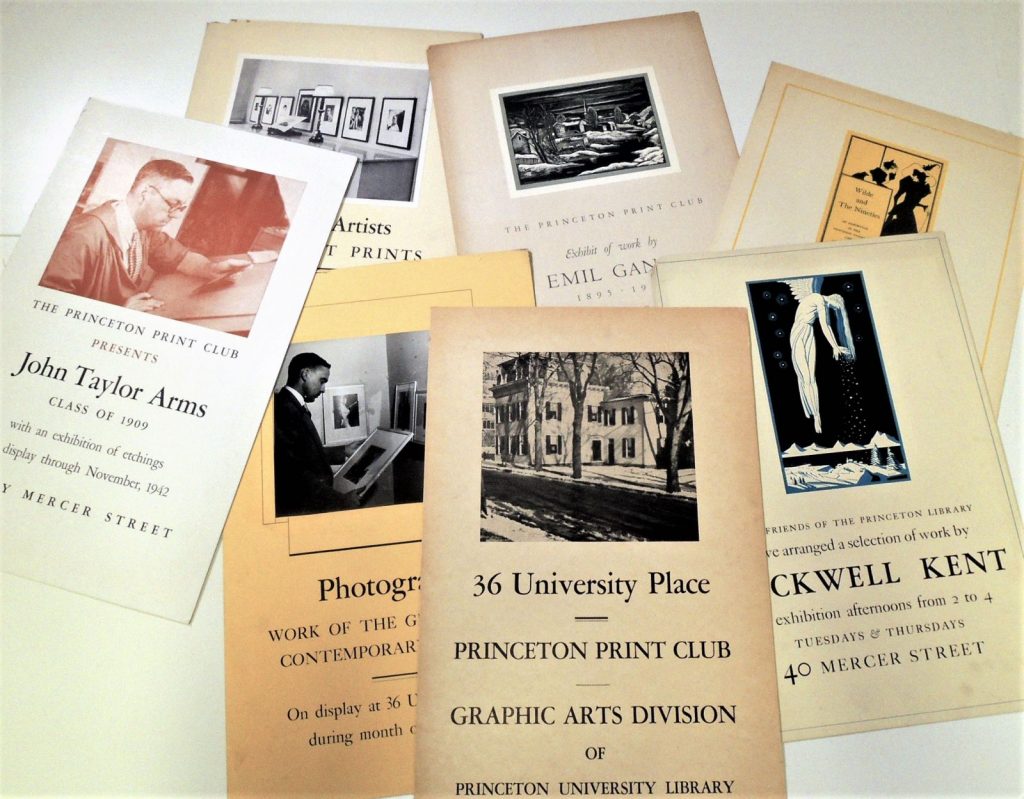

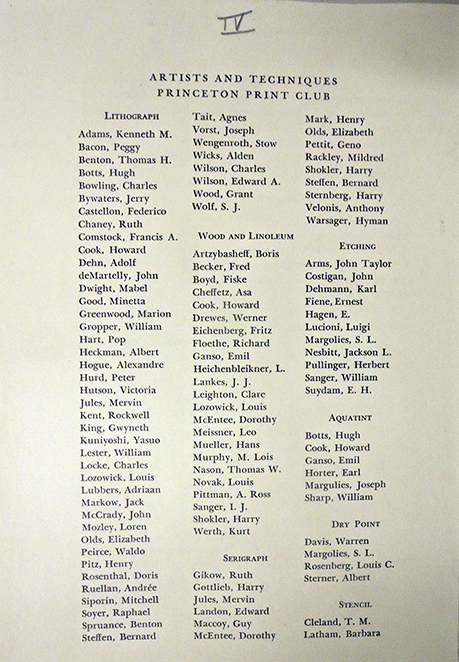

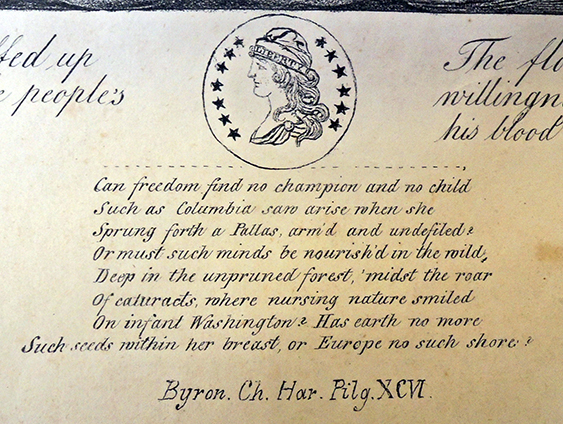

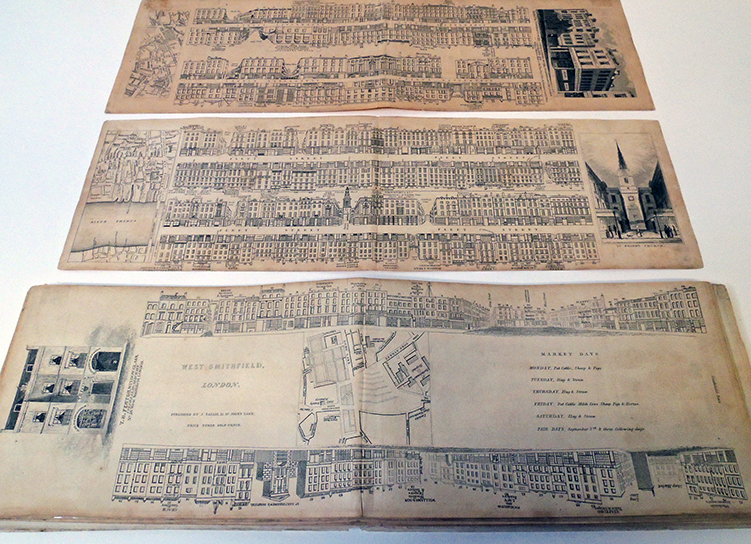

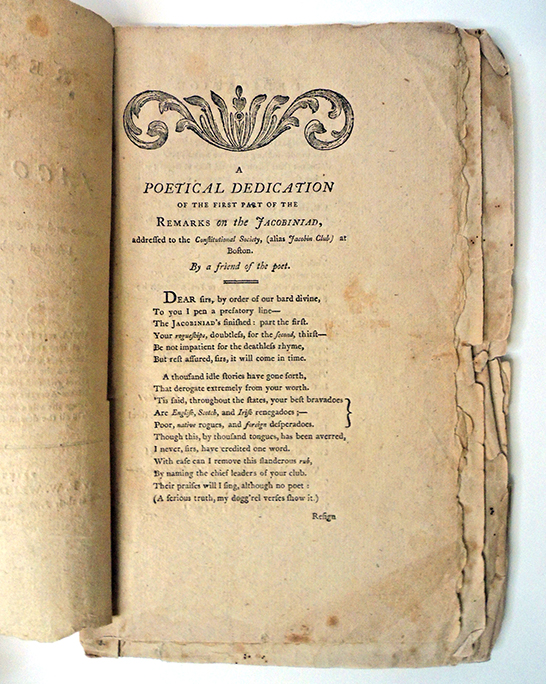

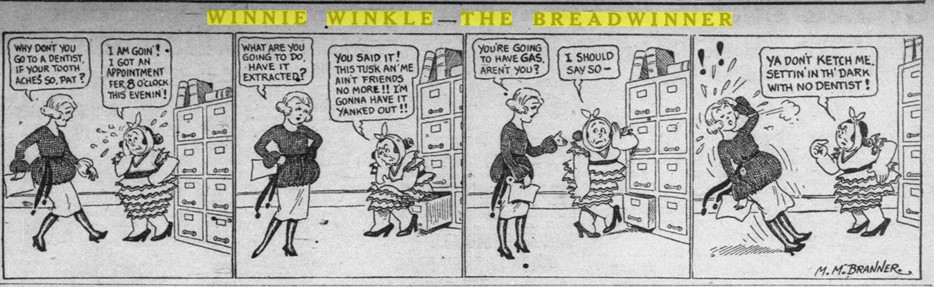

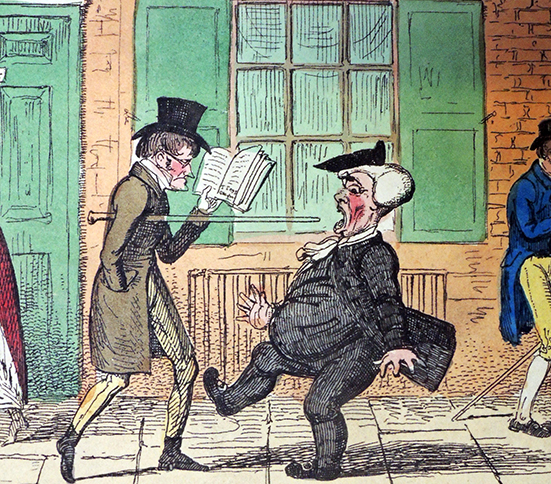

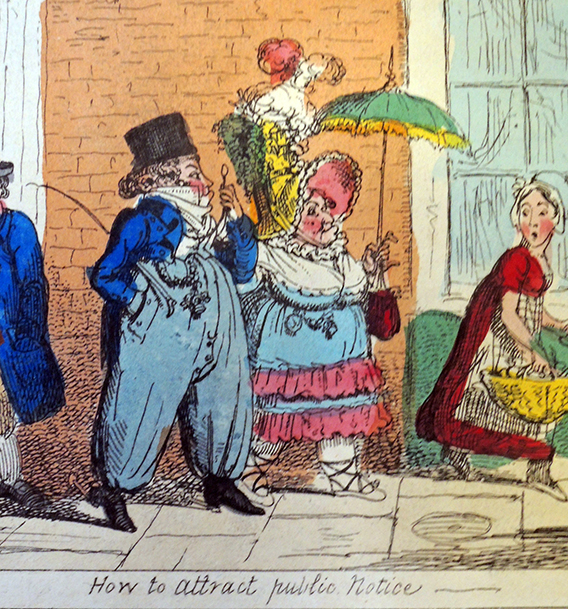

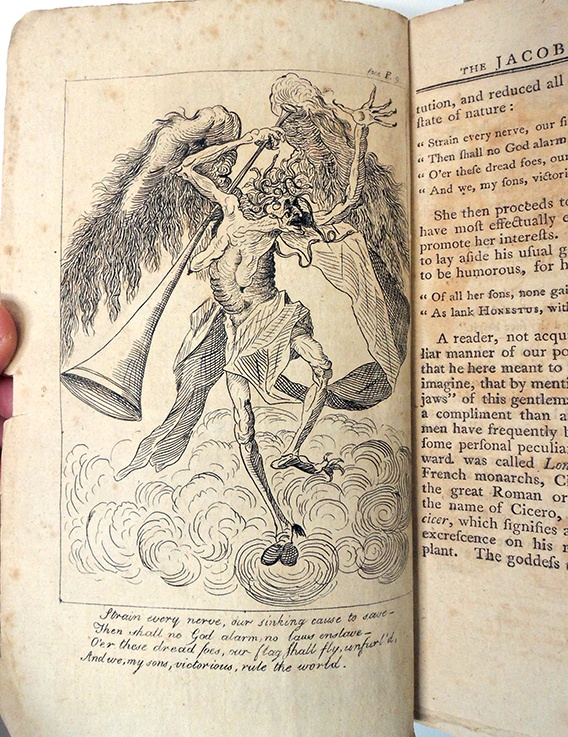

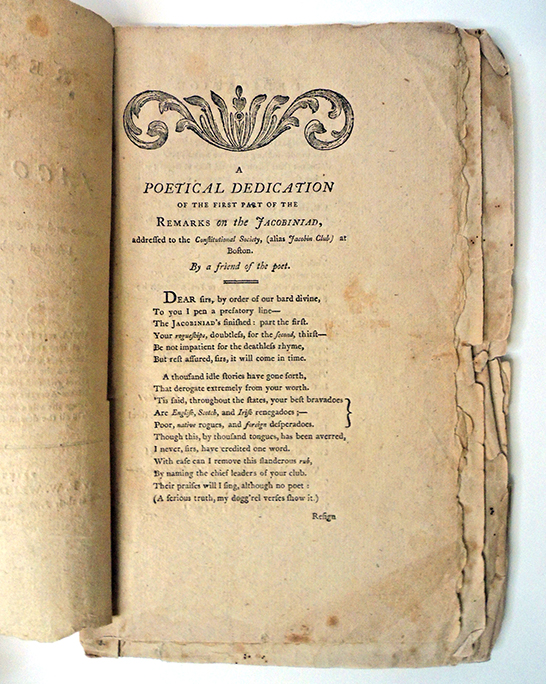

Remarks on the Jacobiniad was a ten-part series published in the Boston Federal Orrery between Dec. 8, 1794 and Jan. 22, 1795, satirizing the Democratic-Republican societies in Boston. Disguised as a serious literary review of a fictitious poem, “The Jacobiniad,” the parts were later published in pamphlet form and attributed to John Sylvester John Gardiner (1765–1830), an Episcopal priest and rector at Trinity Church, Boston (DAB).

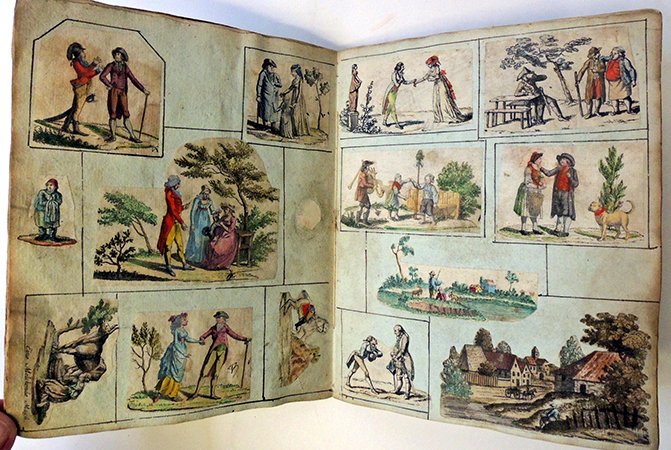

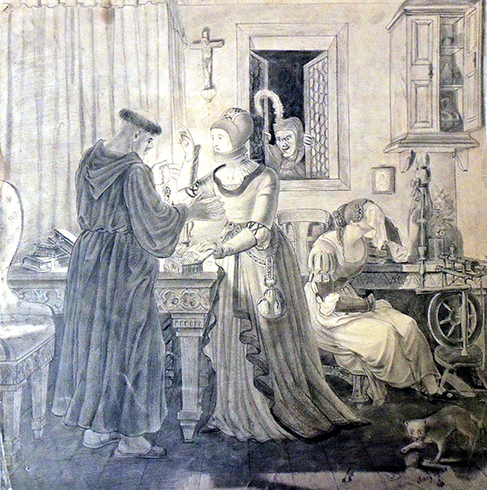

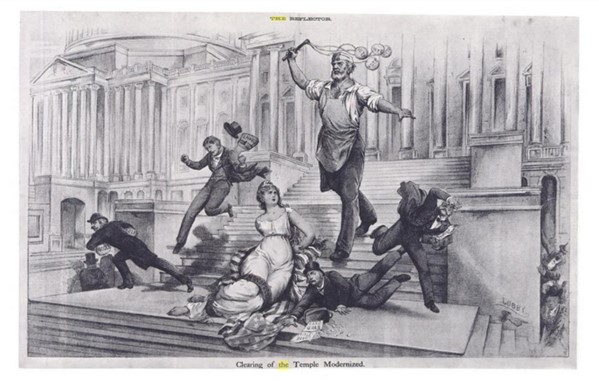

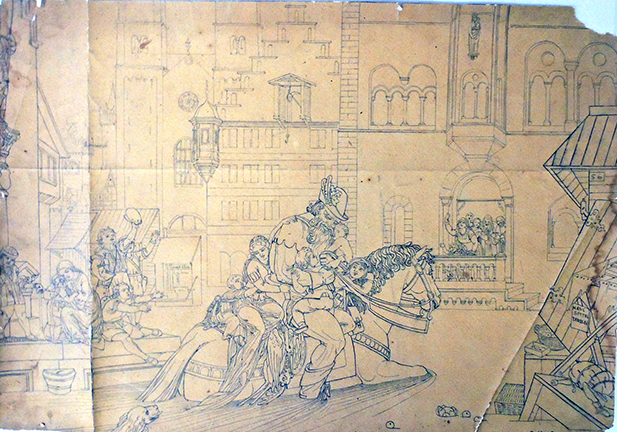

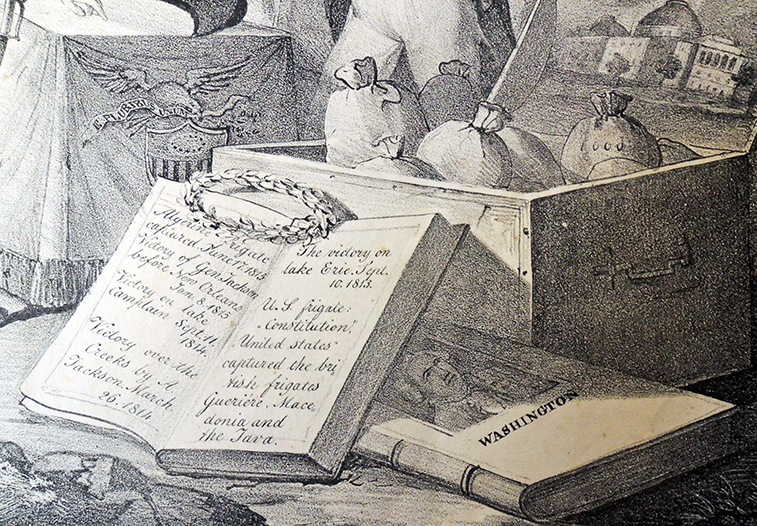

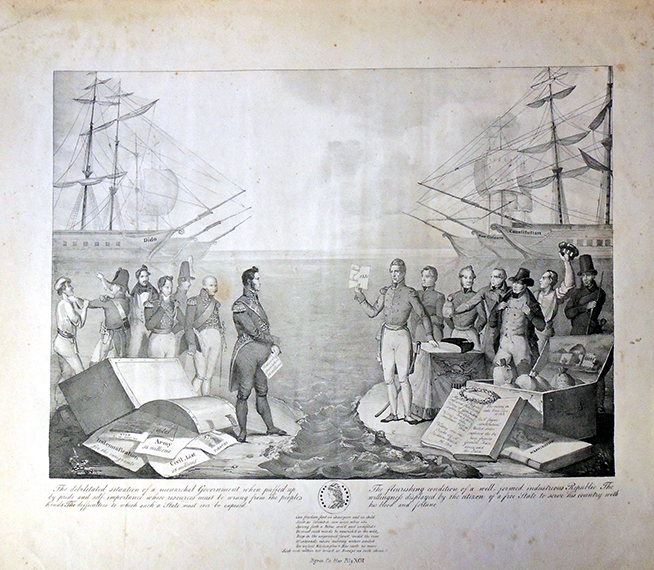

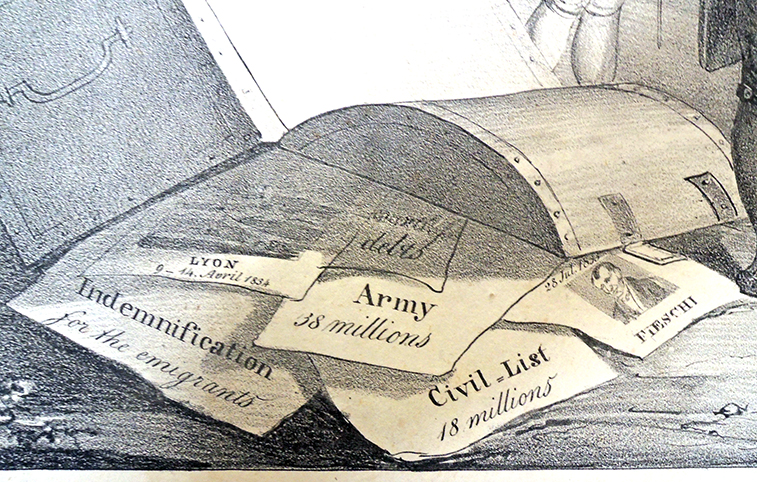

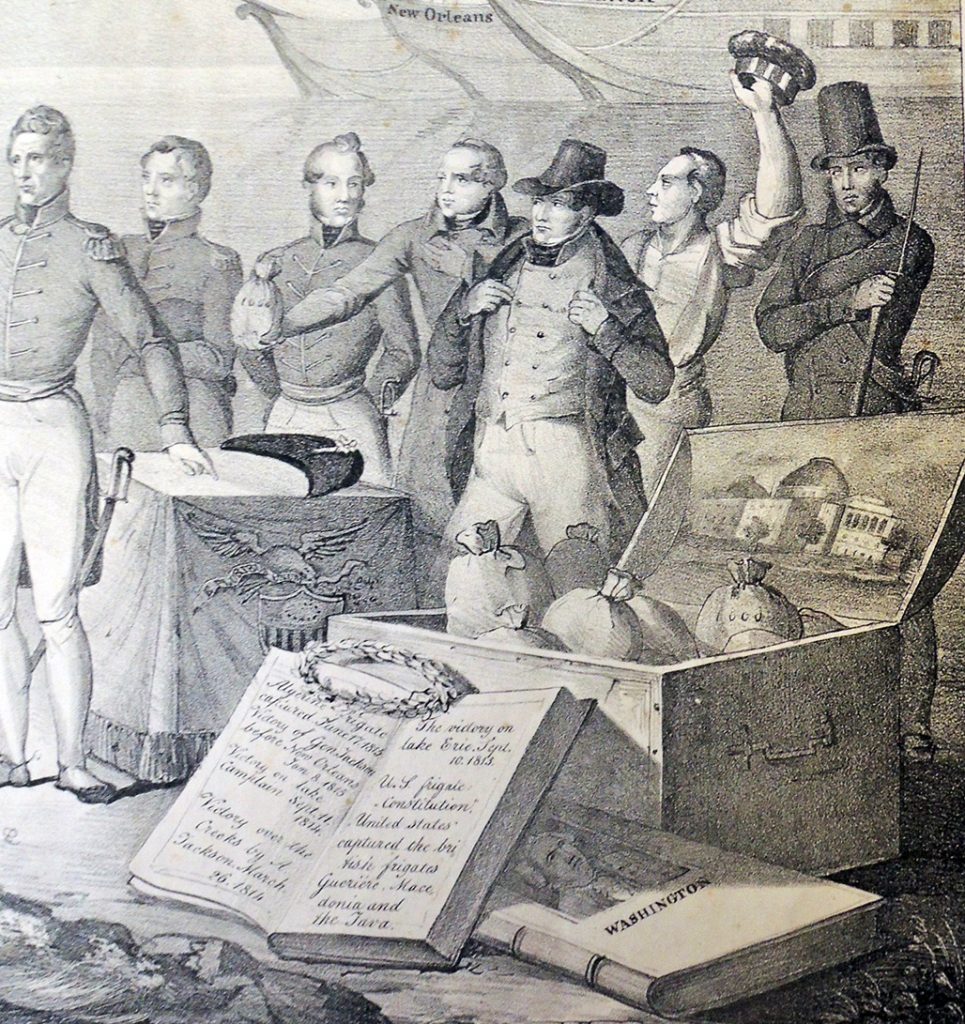

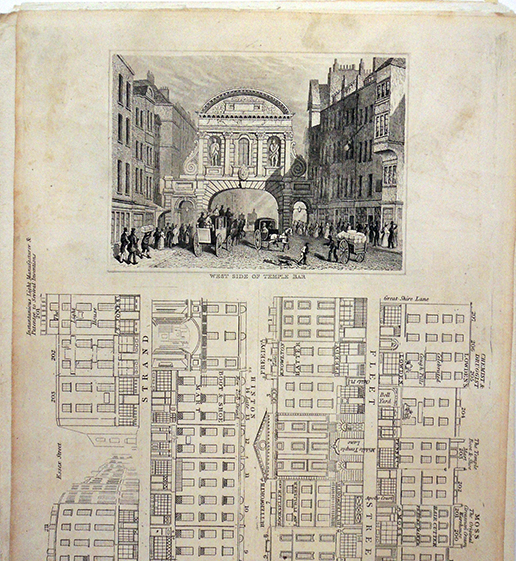

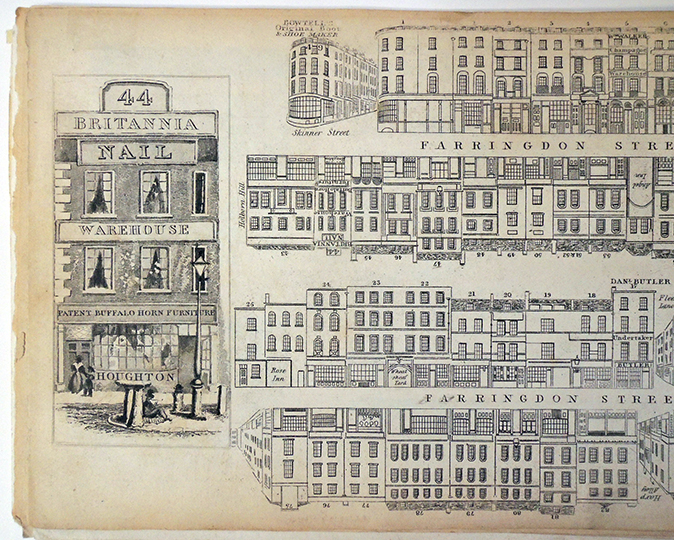

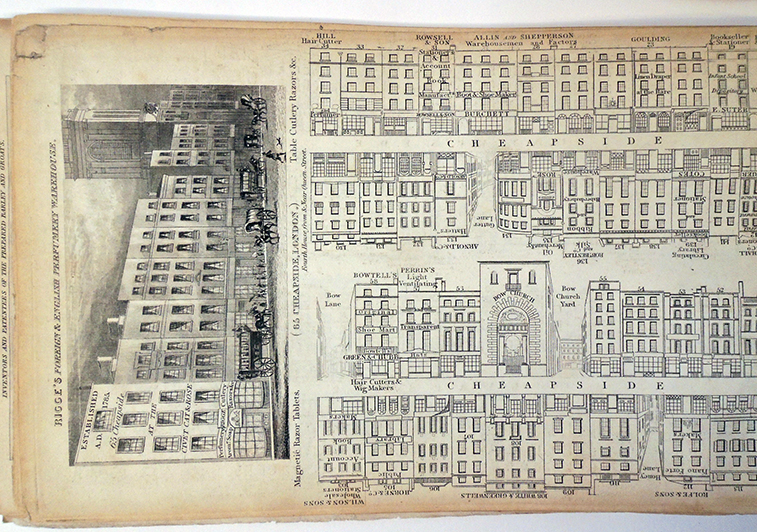

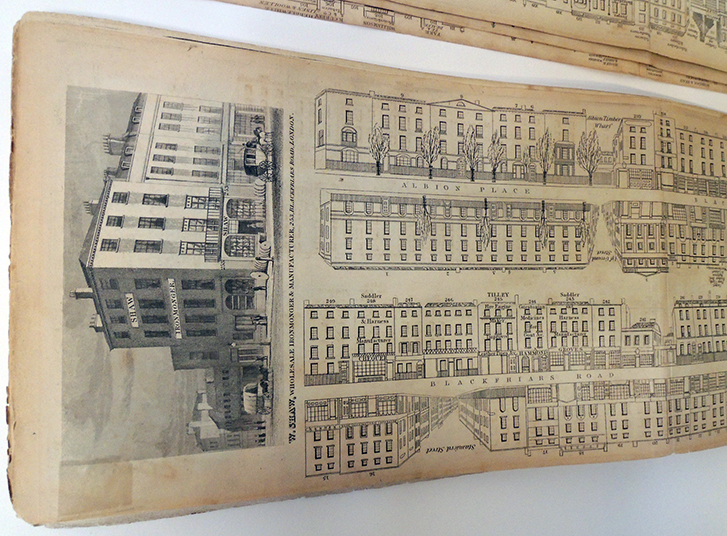

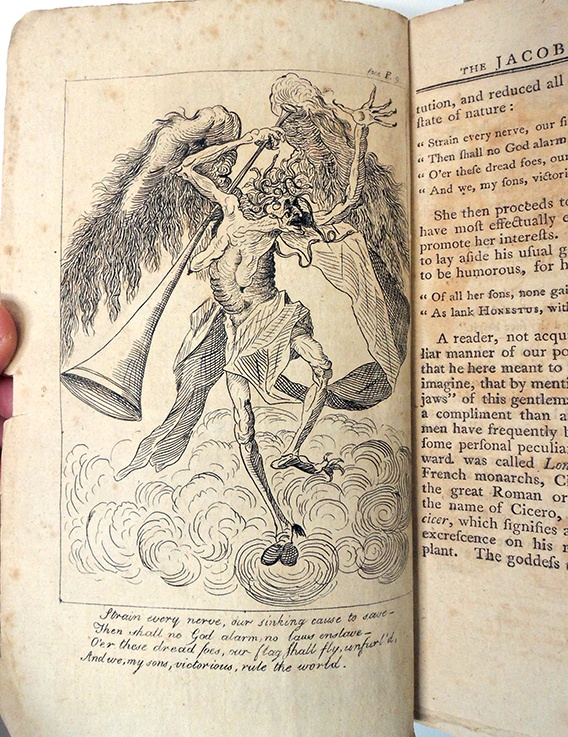

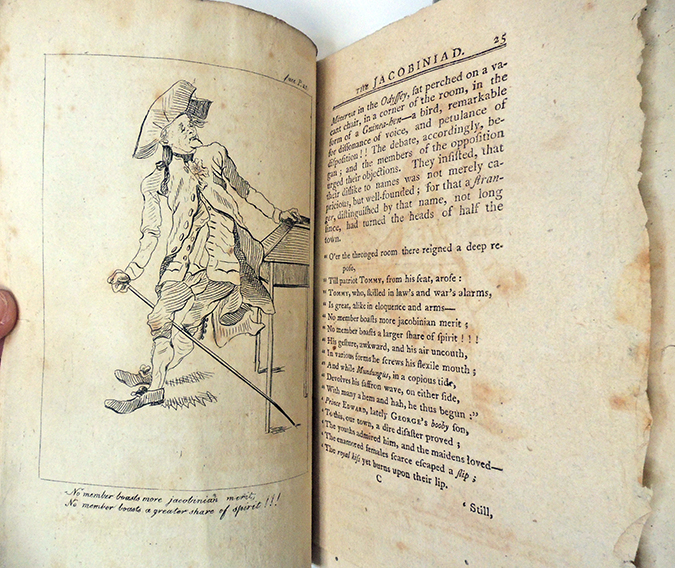

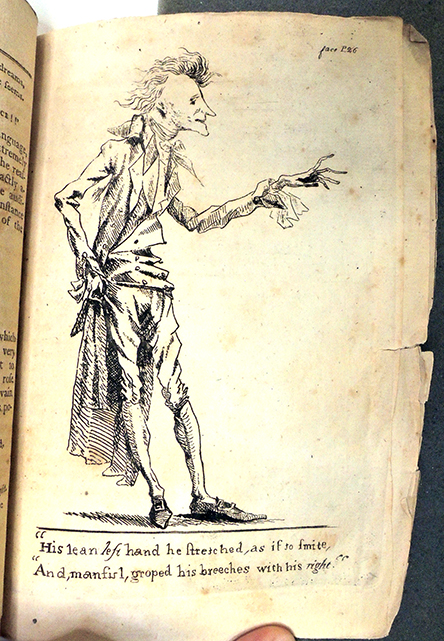

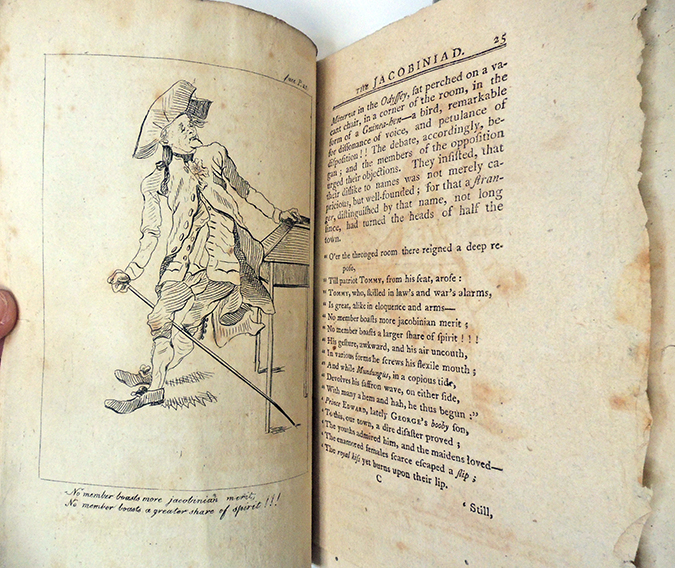

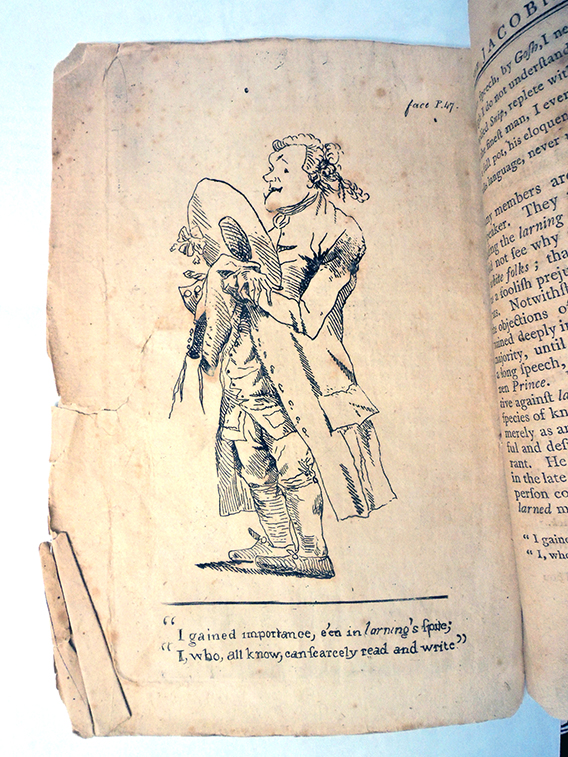

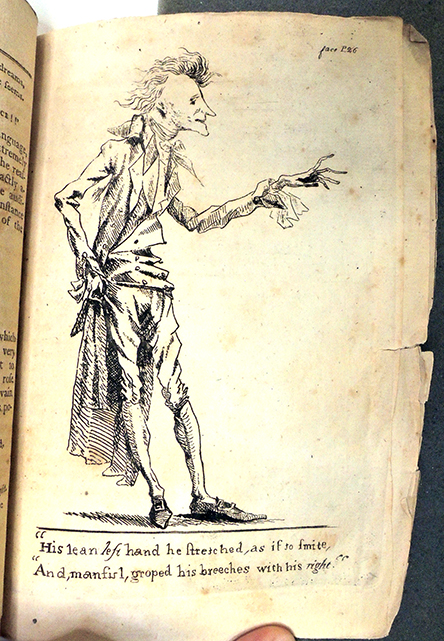

While not the earliest American political caricatures, the six engraved plates in Remarks on the Jacobiniad are rare examples of 18th-century colonial American satire. Various almanacs of the period also contain plates making fun of political figures, such as “Washington with Federal Constitution and Benjamin Franklin in chariot pulled by thirteen freemen, representing the original thirteen states,” from Bickerstaff’s Boston Almanack, or Federal calendar for 1788. Graphic Arts Collection Oversize Hamilton 44.

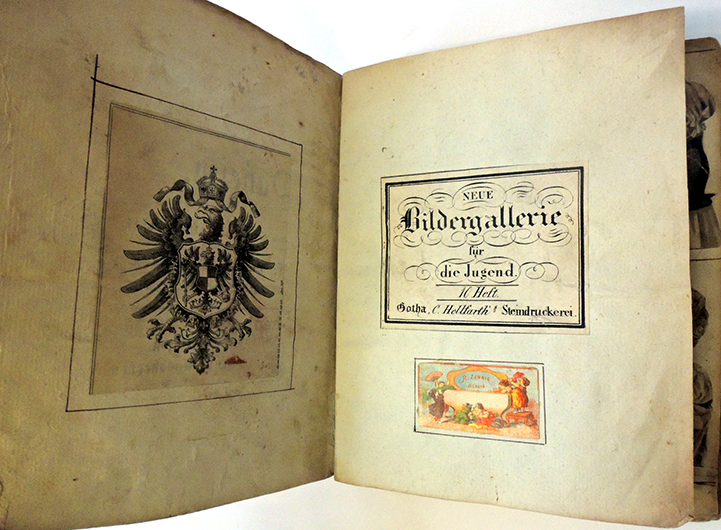

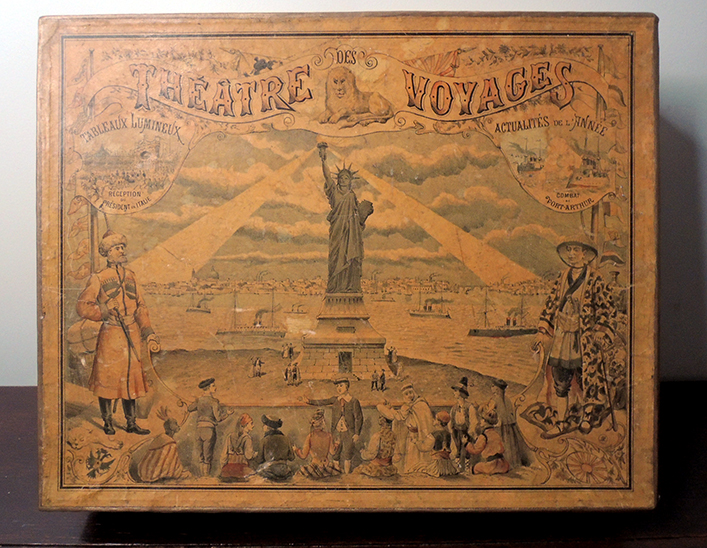

John Sylvester John Gardiner (1765-1830).] Remarks on the Jacobiniad: Revised and corrected by the author; and embellished with Carricatures [sic]. Part First. Boston: E. W. Weld and W. Greenough, 1795. 6 engraved plates. Graphic Arts Collection GAX 2021- in process

John Sylvester John Gardiner (1765-1830).] Remarks on the Jacobiniad: Revised and corrected by the author; and embellished with Carricatures [sic]. Part First. Boston: E. W. Weld and W. Greenough, 1795. 6 engraved plates. Graphic Arts Collection GAX 2021- in process

“Inspired by the political clubs of revolutionary France (the Jacobins being the most famous), American Democratic clubs formed in the early 1790s in most major cities, often boasting among their members some of the most prominent political names of the period (Sam Adams in Boston, the Livingston family in New York). Their increasingly vocal reaction to the Federalist administration prompted a series of mock-epic responses in 1794 and 1795, including Lemuel Hopkins’s The Democratiad, Boston poet John Sylvester John Gardiner’s Remarks on the Jacobiniad, and Democracy: An Epic Poem (Franklin 1970, vi).

In each case, the object of satire is not merely the political views of the Democrats but their preferred mode of discourse, the open “town-meeting”-style forum. Recasting such debates as travesties of the grand debates found in serious epics like The Iliad and Paradise Lost, the Federalist Wits portrayed their Democratic opponents as disorderly buffoons, wholly incapable of governing even their own meetings, much less the nation as a whole.”

–Colin Wells, “Revolutionary Verse,” The Oxford Handbook of Early American Literature Edited by Kevin J. Hayes Mar 2008. DOI: 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195187274.013.0023

“[George] Washington, disturbed by the strong political disagreements of his era and eager to retire to his home, Mount Vernon, eliminated himself as a candidate in 1796. A vigorous campaign between John Adams and Thomas Jefferson ensued, resulting in the election of Adams. These cartoons are caricatures of Democratic-Republicans from a pamphlet containing the satirical poem Remarks on the Jacobiniad. The Republicans were nicknamed Jacobins after the Parisian radicals, reflecting the Republicans’ general support of the French Revolution. Federalists, on the other hand, upheld Washington’s strict course of neutrality and feared the spread of Jacobinism in the country.”

— Laurel Grunat, Mitchel Grunat, and Robert Goehlert, Presidential Campaigns, a Cartoon history, Indiana University Libraries Bloomington, 1976

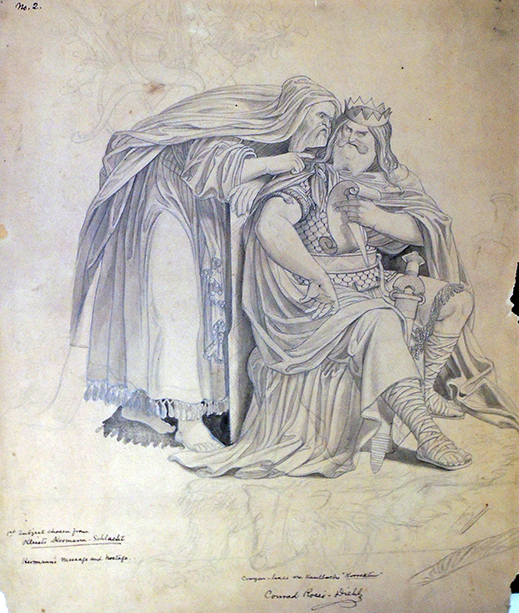

Gilbert Stuart (1755-1828), John Sylvester John Gardiner (1765-1830), c. 1810-1820. Oil on panel. Boston Athenaeum.

Gilbert Stuart (1755-1828), John Sylvester John Gardiner (1765-1830), c. 1810-1820. Oil on panel. Boston Athenaeum.

John Gardiner was born in Wales but spent much of his youth in the West Indies, where his father served for the British government as attorney-general. He was sent to Boston for his education, returning to Britain only at the outbreak of the American Revolution. In 1783, however, he moved permanently to Boston and was eventually named rector of Trinity Church. He was a published author and a founder of the Boston Athenaeum.

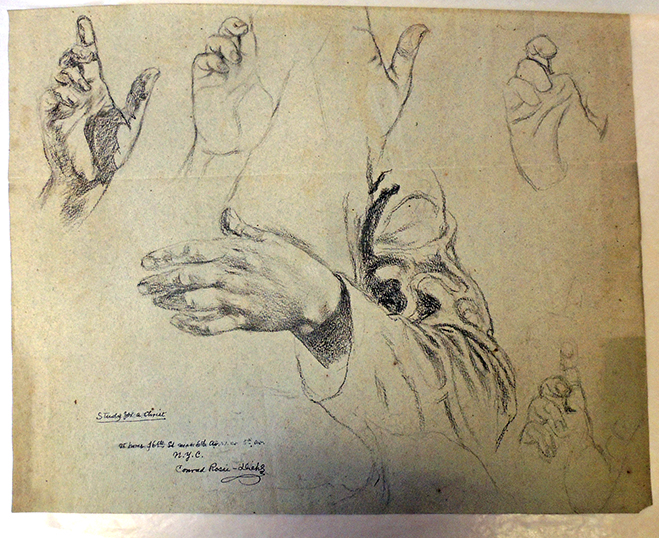

His lean left hand he stretched, as if to smite / And, mansir l, groped his breeches with his right.

His lean left hand he stretched, as if to smite / And, mansir l, groped his breeches with his right.