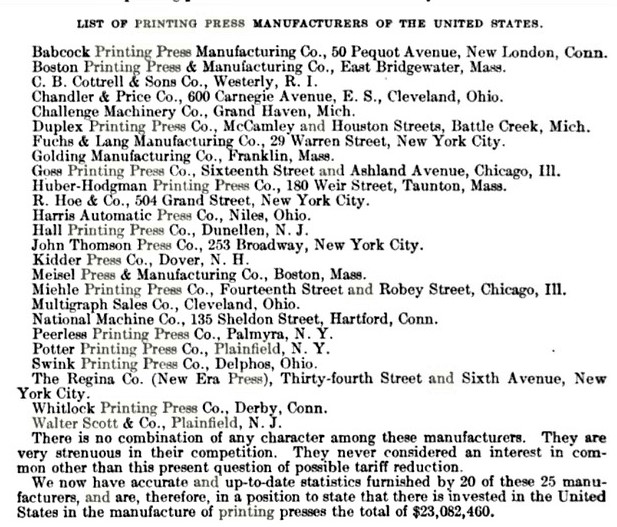

After Chauncey Bradley Ives (1810–1894), Bust of Noah Webster, ca.1840. Plaster cast. (ex) 4766. Gift of Mrs. Theodore L. Bailey.

After Chauncey Bradley Ives (1810–1894), Bust of Noah Webster, ca.1840. Plaster cast. (ex) 4766. Gift of Mrs. Theodore L. Bailey.

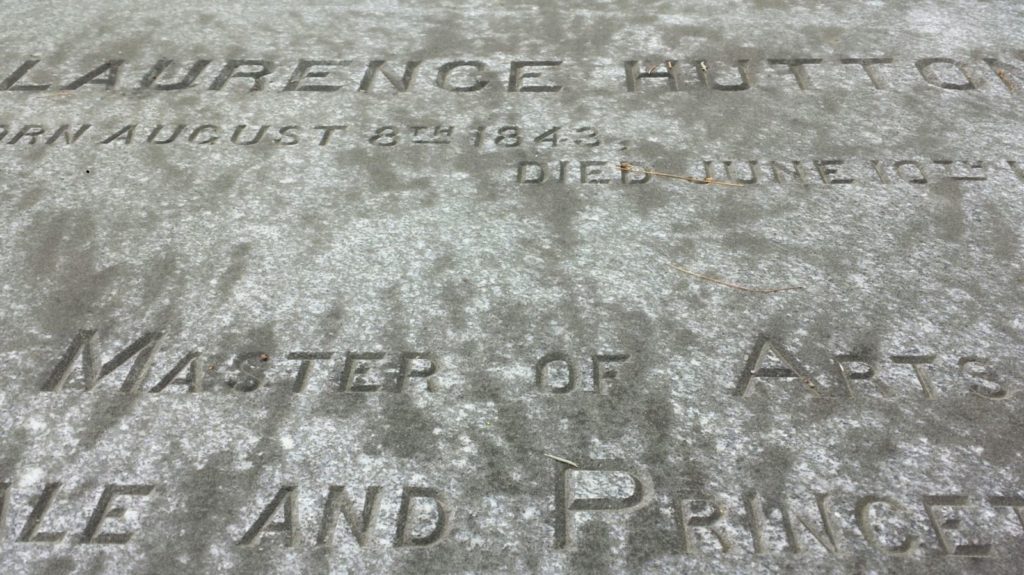

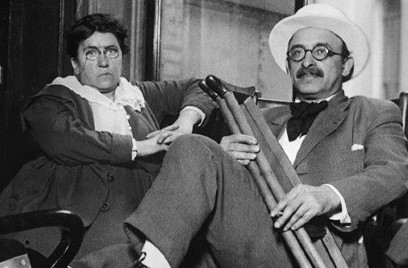

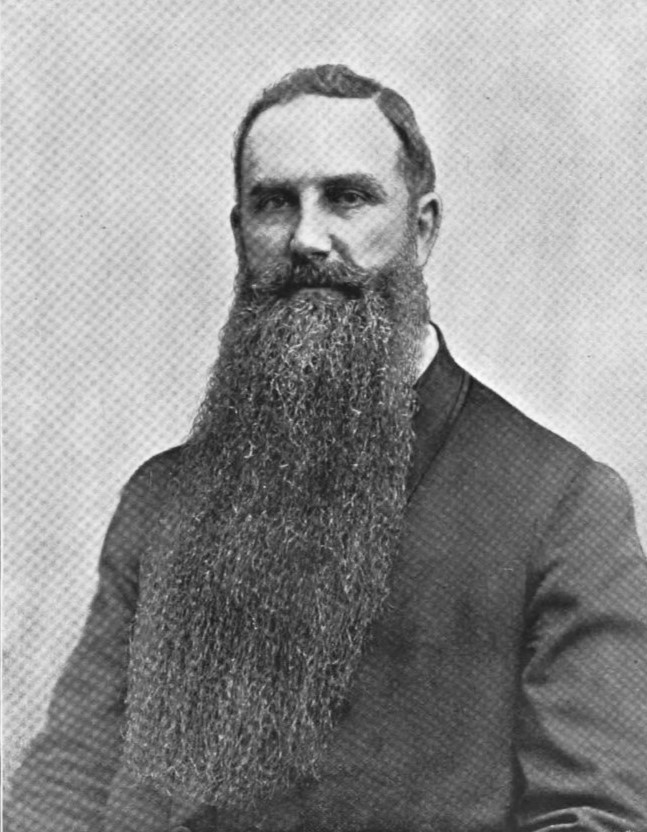

During the 21st-century renovation of Firestone Library, a cast plaster bust of Noah Webster (1758-1843) was relocated from the library tower to the newly constructed special collection vaults. It came with a possible attribution to the 19th-century sculptor John Henri Isaac Browere (1792-1834).

We can now confidently re-attribute the bust to Chauncey Bradley Ives (1810-1894), an American sculptor who worked primarily in the Neo-classic style. Today he is remembered for his portraits of celebrated Americans, both full-length statues and busts, including Noah Webster completed in 1840. Our bust was donated to Princeton by (or in honor of) Mrs. Theodore L. Bailey (died 1961). Mr. and Mrs. Bailey also donated a bronze cast of Ives’ Webster bust to Yale University in 1964, where the University also owns a painted cast plaster version of the bust.

In 1964, a New York Times reporter attended an outdoor auction of the household possessions and furnishings of the late Mrs. Theodore L. Bailey (died 1961). The sale included pieces belonging to Noah Webster, of whom Mrs. Bailey was a direct descendant.–“Picnicking’s Half the Fun at Auction,” New York Times November 14, 1964. This may explain their interest in having Webster’s likeness at the universities. Mr. Theodore Bailey, Jr. was a member of the Princeton Class of 1926 and he also presented a bronze bust of Webster to the Mead Art Museum, Amherst College.

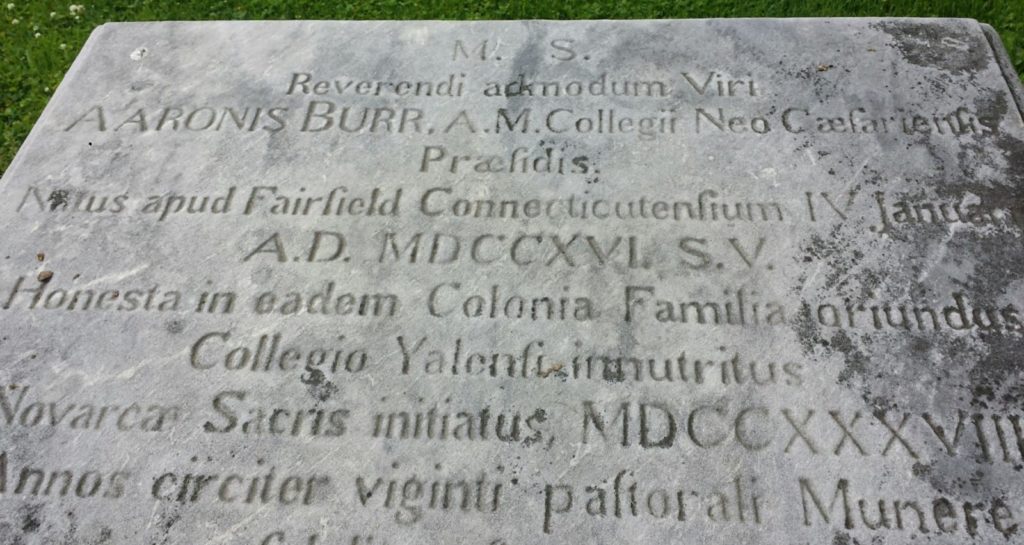

Noah Webster, Jr. (1758-1843), a graduate of Yale, wrote the first American dictionary, entitled A Compendious Dictionary of the English Language (1806) and followed it with An American Dictionary of the English Language (1828). Before the age thirty, Webster had already published a three volume study: A Grammatical Institute of the English Language, including a speller (1783), a grammar (1784), and a reader (1785). See more: https://www.merriam-webster.com/about-us/americas-first-dictionary

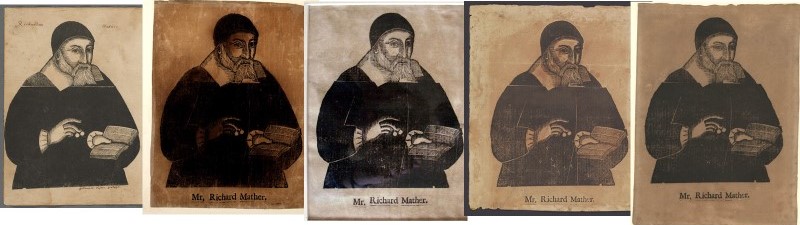

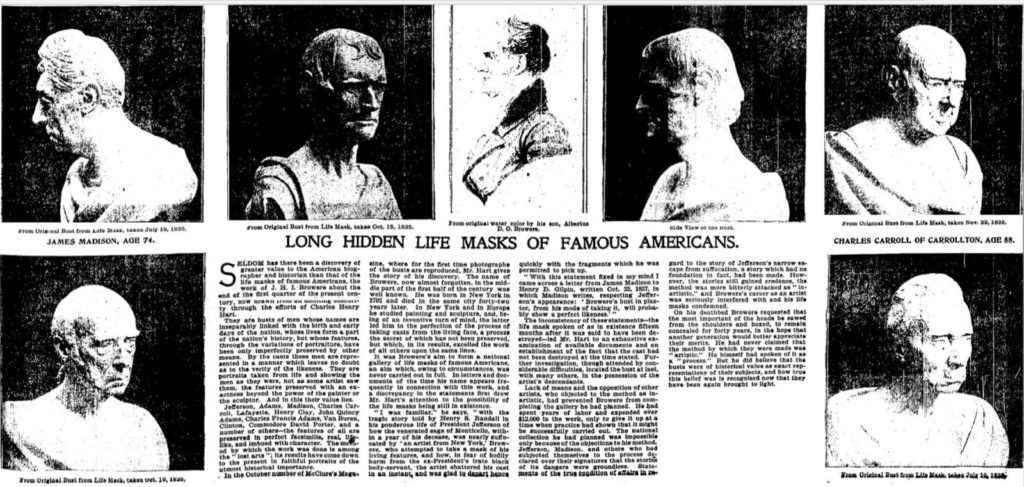

The former attribution was not a bad guess. In 1825, John Henri Isaac Browere (1792-1834) began using plaster life masks to create full three-dimensional busts of noted Americans, such as Thomas Jefferson, John Adams, De Witt Clinton, and Dolley Madison. It was his hope to establish a National Gallery of Notable Americans, but critics were divided on the merits of his technique, dubbing him a mechanic and calling his New York studio a “plaster factory.”

At his death, Browere’s collection of plasters was hidden from view until 1897, when McClure’s reporter Charles Henry Hart tracked them down and published “Unknown Life Masks of Great Americans…The Story of Their Production, Concealment from the Public, and Recent Recovery,” —McClure’s Magazine 9 1897. The Chicago Daily Tribune followed this with a front page article “Long Hidden Life Masks of Famous Americans” and the plaster busts were exhibited at the Chicago World’s Fair. Later, most of the collection was donated to the Fenimore Art Museum in Cooperstown, New York (formerly the New York State Historical Association). Browere’s work in plaster was not unlike the bust of Webster.

See: Life Masks of Noted Americans of 1825 by John H. I. Browere (Cooperstown, N.Y., The New York State Historical Association [1951?]). Firestone Library NB1293.N49