This week it’s hard to concentrate with the continuing inequities in the United States so blatantly exposed. While it is necessary for everyone to do better, here are just a few recent acquisitions that might help to highlight interesting and important Black lives, for upcoming classes.

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

Here is a small selection from a group of approximately 120 press and wire photographs dating from the early 1960s through 1980, recently acquired by the Graphic Arts Collection with the help of Steven Knowlton, Librarian for History and African American Studies. These heavily used prints all relate to the Civil Rights movement in the United States, documenting protests, marches, sit-ins, and police confrontations in Atlanta, Alabama, Chicago, Louisiana, Massachusetts, Mississippi, and Washington, D.C.

[left] “Selma, Ala., Mar. 12 — The ‘Wall’ is down — Jubilant demonstrators held aloft a rope barricade after it was cut down in Selma, Ala. today [by] public safety director Wilson Baker. The demonstrators had sung [unclear] referring to the barricade as the Berlin wall and Baker unexpectedly walked over and severed it. He said “nothing has changed” and still refused to allow the non-stop demonstrators to march. …1965.” Read more about 1965 events in Selma: https://www.cnn.com/2013/09/15/us/1965-selma-to-montgomery-march-fast-facts/index.html

[left] “Selma, Ala., Mar. 12 — The ‘Wall’ is down — Jubilant demonstrators held aloft a rope barricade after it was cut down in Selma, Ala. today [by] public safety director Wilson Baker. The demonstrators had sung [unclear] referring to the barricade as the Berlin wall and Baker unexpectedly walked over and severed it. He said “nothing has changed” and still refused to allow the non-stop demonstrators to march. …1965.” Read more about 1965 events in Selma: https://www.cnn.com/2013/09/15/us/1965-selma-to-montgomery-march-fast-facts/index.html

Read more about this photo-archive: https://graphicarts.princeton.edu/2018/02/23/the-civil-rights-movement-in-america/

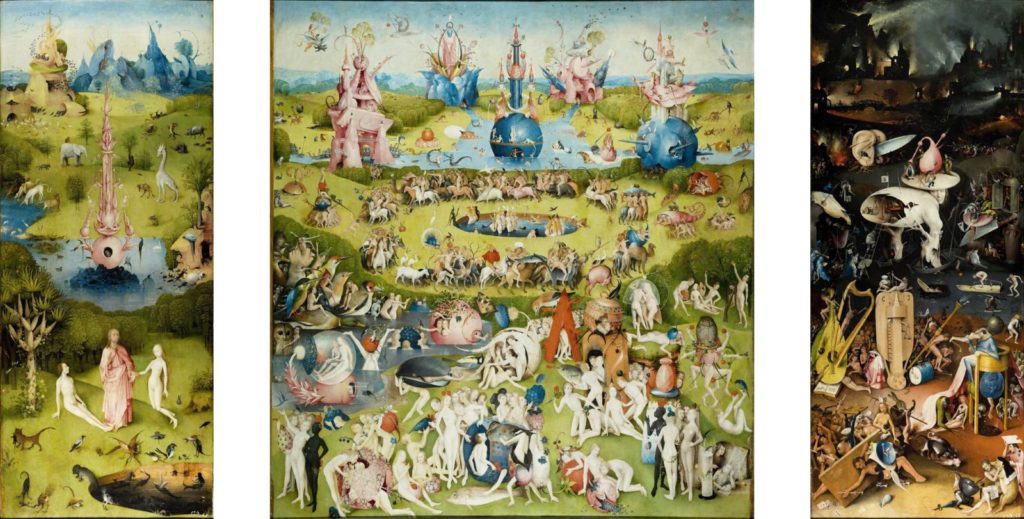

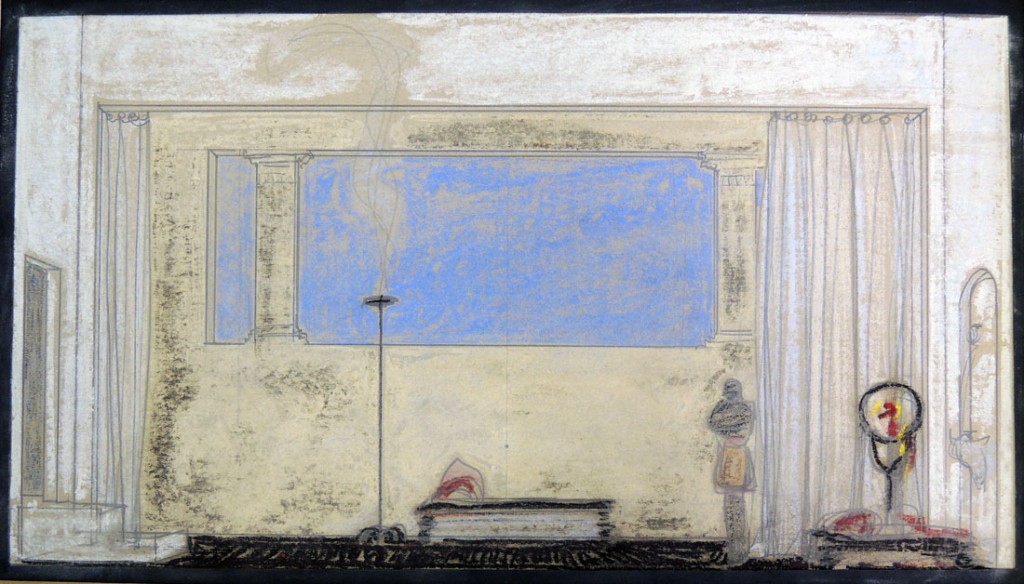

This beautiful design by Robert Edmond Jones (1887-1954), is for the production of Simon the Cyrenian, one of three short plays that opened April 5, 1917 at New York’s Garden Theater under the heading Three Plays for a Negro Theater. Jones not only designed but directed the three productions, which each featured all Black casts. As one of the first straight plays to feature Black actors exclusively, without melodrama or burlesque, this production is often cited as the beginning of the period we call the Harlem renaissance.

W. E. B. Du Bois (1868-1963) transcribed the outpouring of critical review in The Crisis, beginning with poet Percy MacKaye’s comment, “It is indeed an historic happening. Probably for the first time, in any comparable degree, both races are here brought together upon a plane utterly devoid of all racial antagonisms—a plane of art in which audiences and actors are happily peers, mutually cordial to each others’ gifts of appreciation and interpretation.” Read more; https://graphicarts.princeton.edu/2014/03/12/robert-edmond-jones-directs-an-all-black-cast/

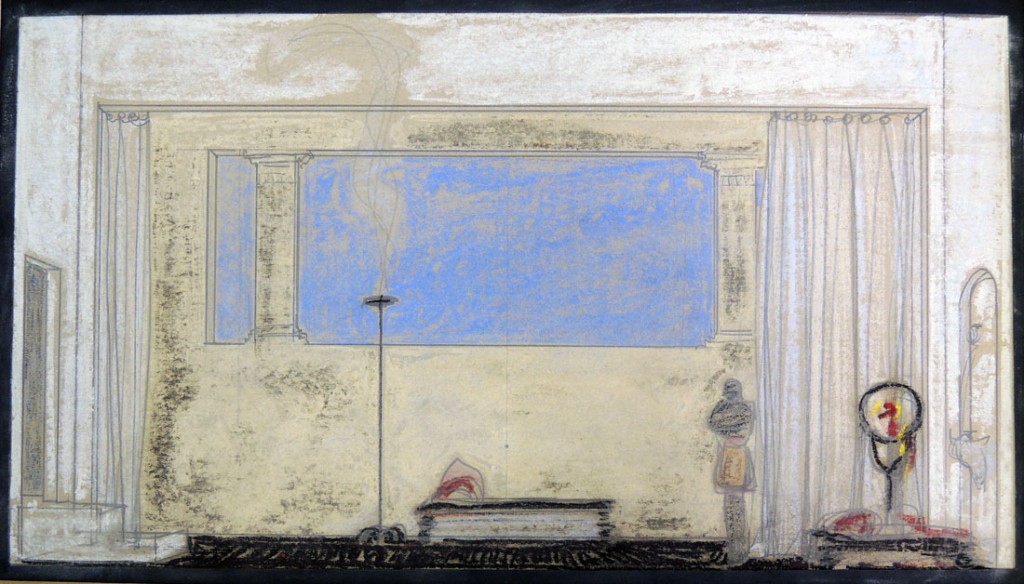

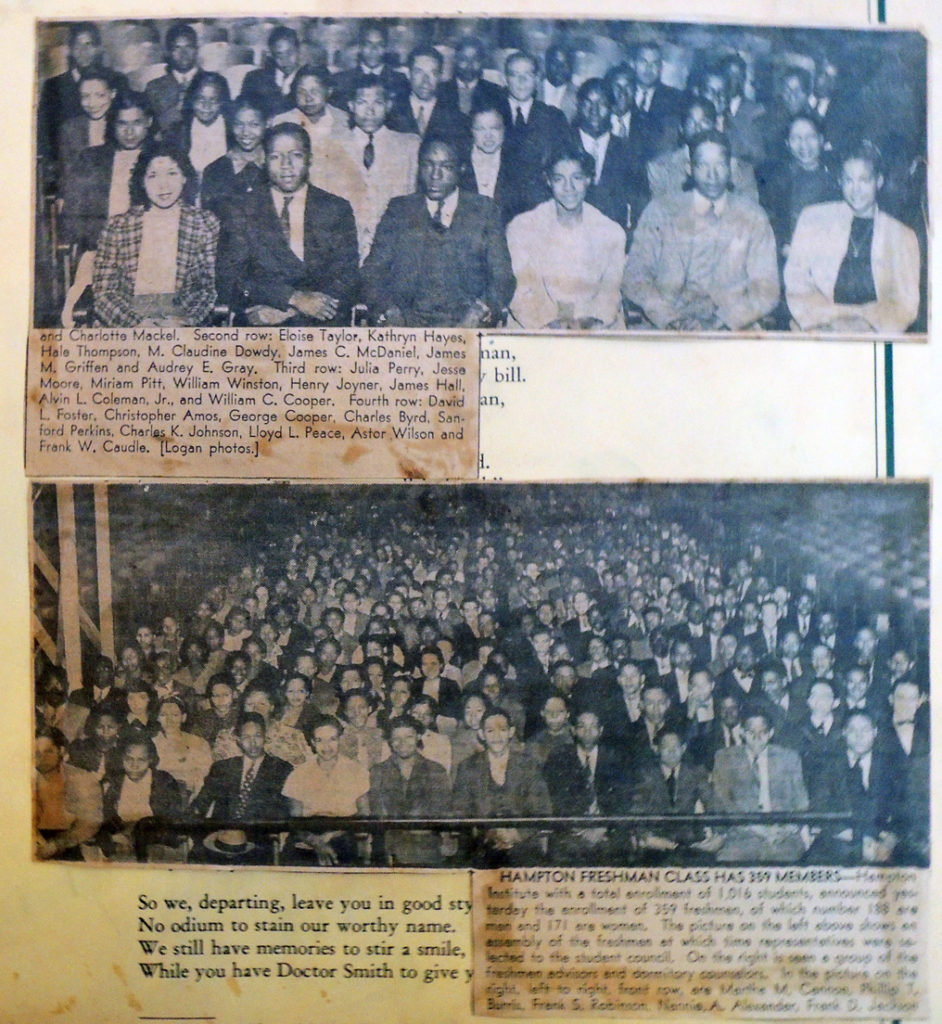

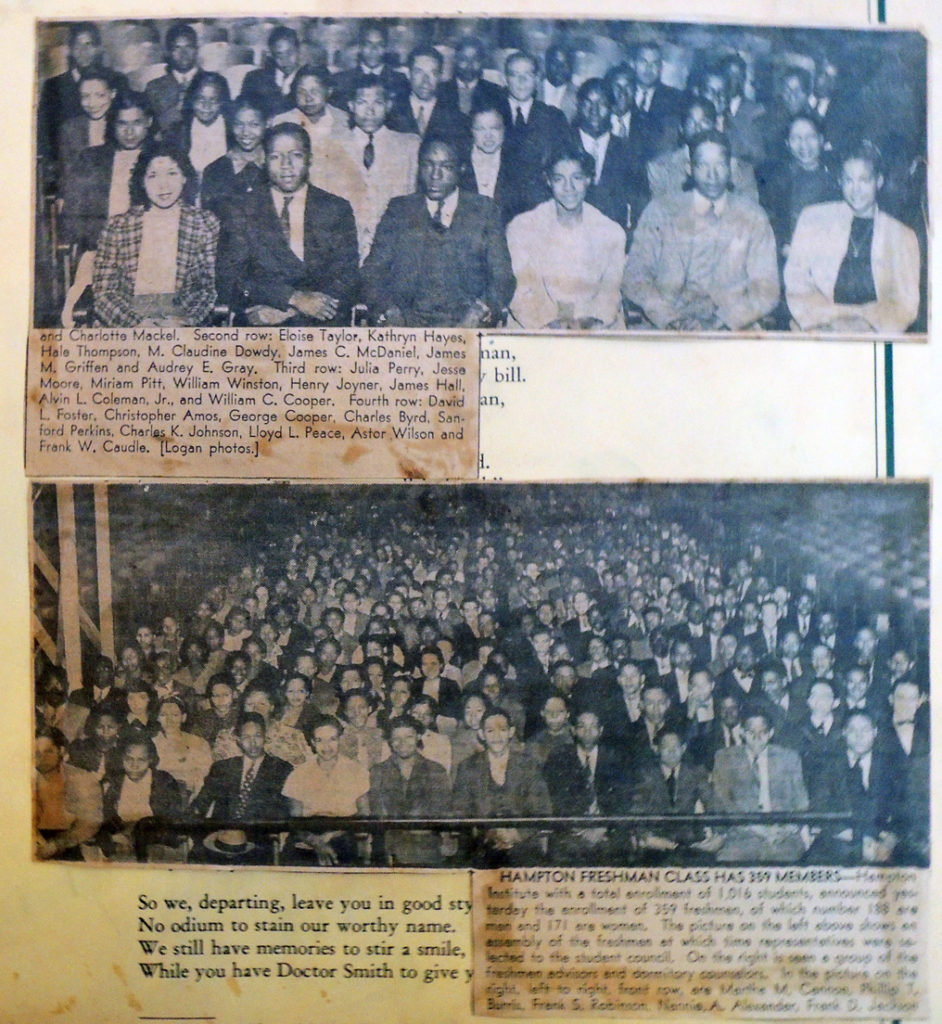

During his years as an undergraduate at the Hampton Institute, Willis J. Hubert (1919-2007) kept a scrapbook, filling it with programs, report cards, newspaper articles, and many informal photographs of his classmates. This enormous volume bound in carved wood boards, 30 x 46 x 7 cm, provides an intimate look at undergraduate life at this primarily black school from 1936 to 1940.

During his years as an undergraduate at the Hampton Institute, Willis J. Hubert (1919-2007) kept a scrapbook, filling it with programs, report cards, newspaper articles, and many informal photographs of his classmates. This enormous volume bound in carved wood boards, 30 x 46 x 7 cm, provides an intimate look at undergraduate life at this primarily black school from 1936 to 1940.

According to his obituary, published in The Atlanta Journal-Constitution from May 15 to May 17, 2007, Hubert went on to have a distinguished military career in which he achieved the rank of Lieutenant Colonel. Not long after he graduated from the Hampton Institute, he entered the U.S. Air Force and trained at Tuskegee Army Air Field, where Hubert was one of the original Tuskegee Airmen.

Hubert became the first African American to earn an M.A. and Ph.D. (New York University) while on active duty, as well as the first to complete the Harvard Business School (Military Co-op) Statistics Training Program. Read more: https://graphicarts.princeton.edu/2018/05/04/undergraduate-life-at-the-hampton-institute/

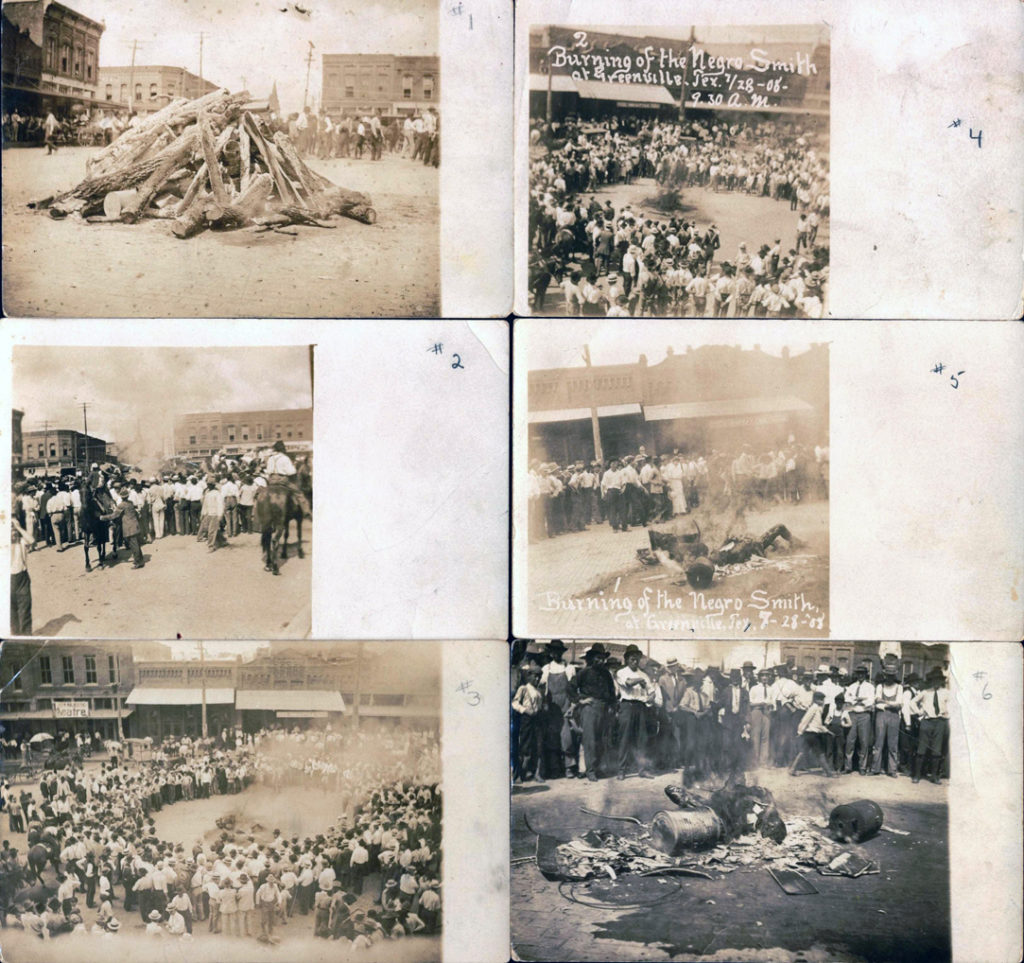

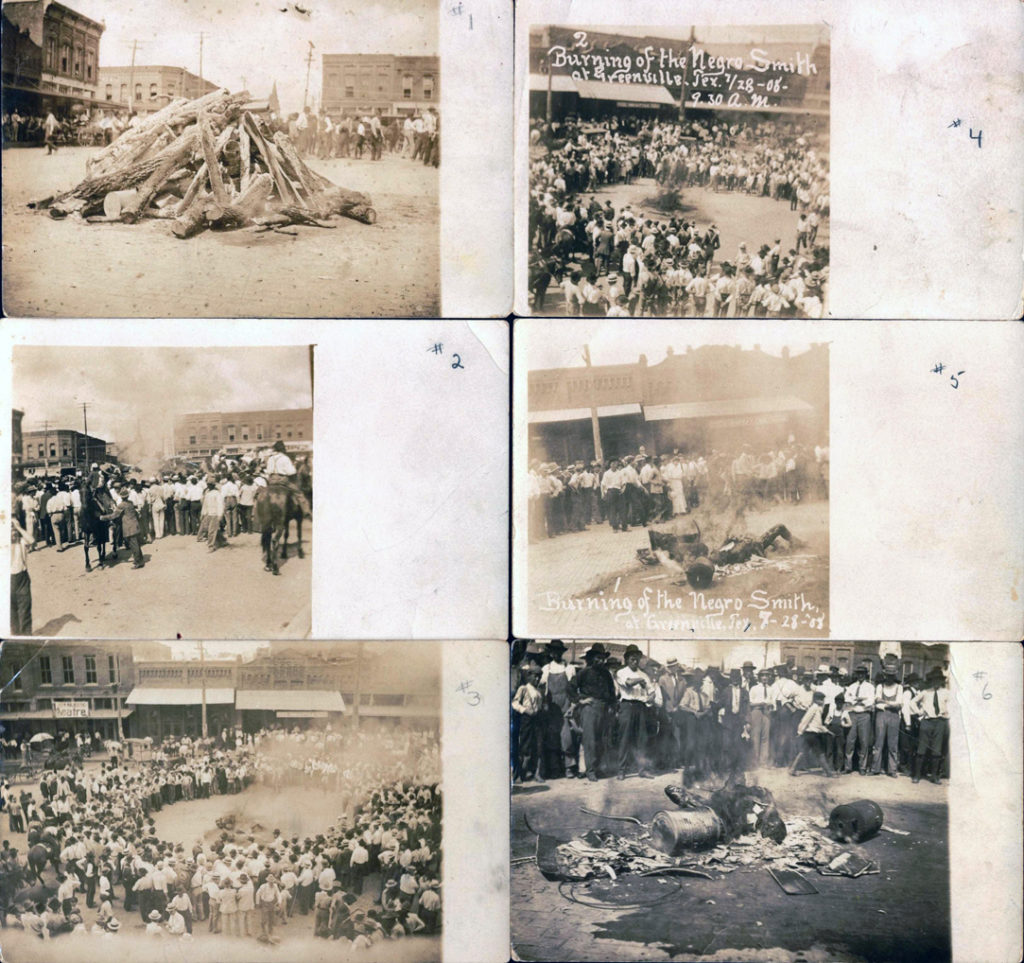

The Graphic Arts Collection recently acquired a set of photographic postcards documenting the “Burning of the Negro Smith.” Two are captioned in white ink. None of them were ever addressed or mailed. The postcards came in a plain envelope marked with the caption in pencil: “Greenville, TX, 28 July 1908”.

The Graphic Arts Collection recently acquired a set of photographic postcards documenting the “Burning of the Negro Smith.” Two are captioned in white ink. None of them were ever addressed or mailed. The postcards came in a plain envelope marked with the caption in pencil: “Greenville, TX, 28 July 1908”.

“Ted Smith, aged 18 years old, was accused of raping a young white woman in Clinton, Texas. He was arrested and brought to jail in nearby Greenville. A mob took him from his cell at eight the next morning. Rather than the usual hanging, they covered him under a pile of wood, doused him with kerosene, and burned him alive in the center of town, in front of a large crowd. The postcards depict the horrible scene, with the crowd gathered around the fire. Read more: https://graphicarts.princeton.edu/2018/05/03/the-murder-of-ted-smith-in-1908/

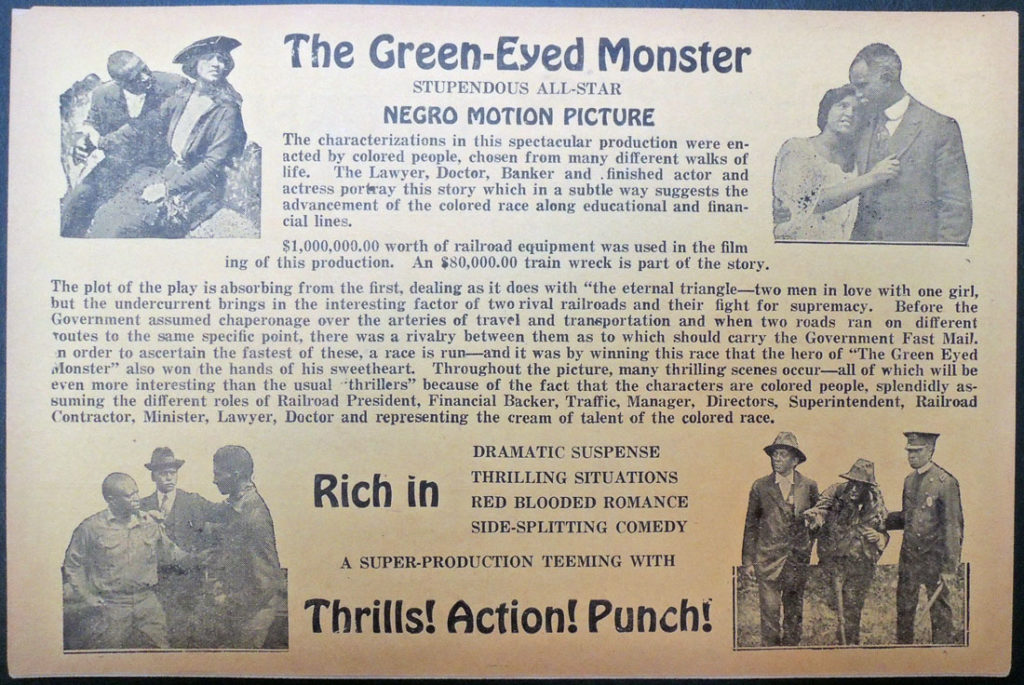

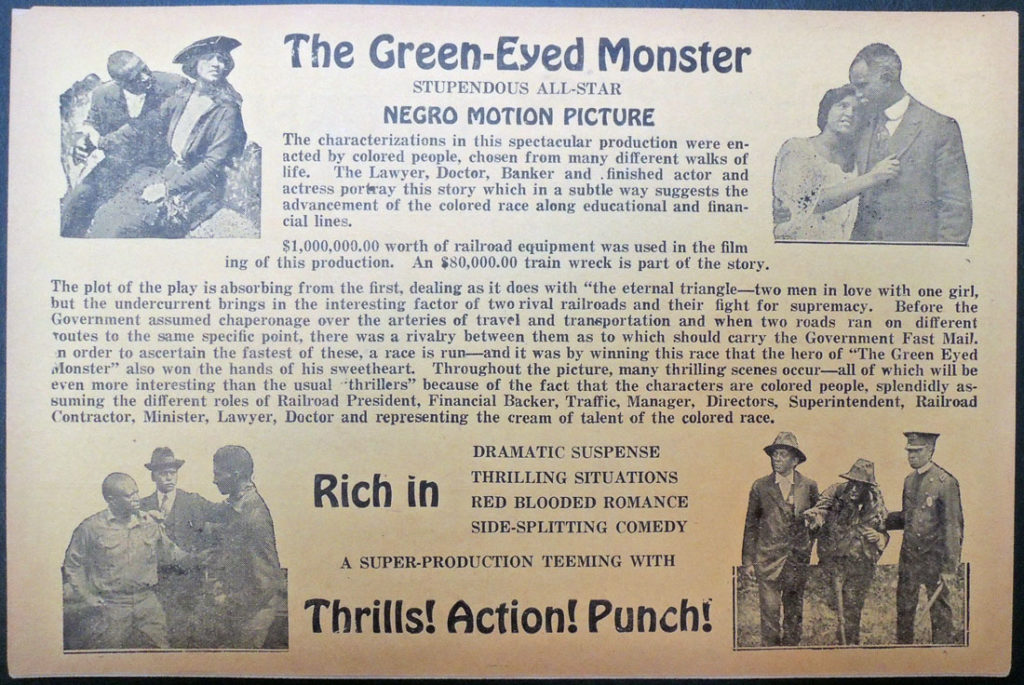

The Graphic Arts Collection acquired a rare promotional brochure for the Norman Film Company’s 1919 silent movie, The Green Eyed Monster, its first production with an all Black cast. Billed as a “Stupendous All-Star Negro Motion Picture,” audiences found it long and so, Norman had the film cut from eight-reels to five-reels. A second release in 1920 led to great success. Although no portion of the film survives, reviews list the actors as Jack Austin, Louise Dunbar, Steve Reynolds, and Robert A. Stuart.

“The first film company devoted to the production of race movies was the Chicago-based Ebony Film Company, which began operation in 1915. The first black-owned film company was The Lincoln Motion Picture Company, founded by the famous Missourian actor Noble Johnson in 1916. However, the biggest name in race movies was and remains Oscar Micheaux, an Illinois-born director who started The Micheaux Book & Film Company in 1919 and went on to direct at least forty films with predominantly black casts for black audiences.”–The New Encyclopedia of Southern Culture: Volume 18 (2011).

Read more: https://graphicarts.princeton.edu/2018/01/24/brochure-for-all-colored-cast-silent-film/

Eric Avery, USA Dishonor and Disrespect (Haitian Interdiction 1981-1994), 1991. Linoleum block print on a seven-color lithograph printed on mold made Okawara paper. 46½ x 34 inches. Edition: 30. Graphic Arts Collection 2014- in process.

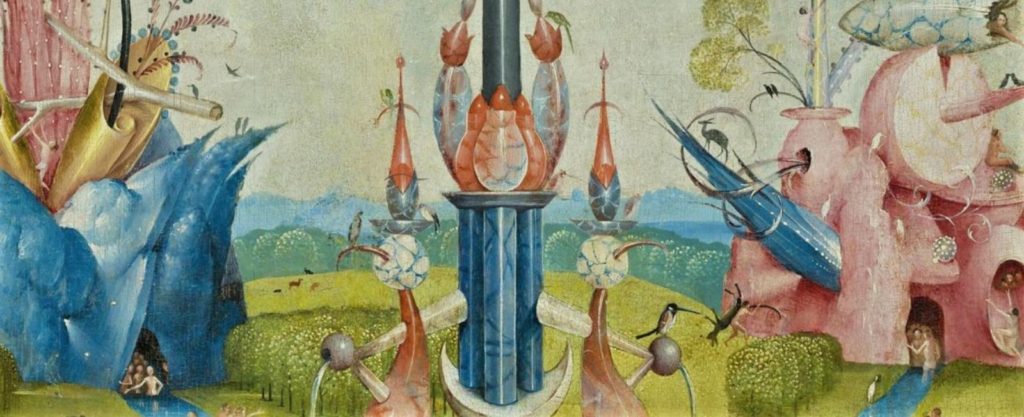

Dr. Eric Avery incorporates his medical practice with his activist art, delving into such themes as infectious diseases, human rights abuse, and the death penalty, among others. Many of his complex prints appropriate one or more iconic art historical images into contemporary events. A few examples are now at Princeton University.

On July 14, 1990, The New York Times reported, “Bahamas Facing More Questions As It Buries 39 Drowned Haitians.” The story continued “Thirty-nine Haitians fleeing their impoverished Caribbean island drowned when their sailboat capsized and sank in choppy seas while being towed by Bahamian authorities, Government officials said. No explanation for what caused the sinking was given.” Published by the Tamarind Institute, Avery’s complex linocut incorporates the facts of the 1990 tragedy with three separate art historical paintings: Theodore Gericault’s The Raft of the Medusa, 1824; John Singleton Copley’s Watson and the Shark, 1778; and Rembrandt’s Christ in the Storm on the Sea of Galilee, 1633.

Read more: https://graphicarts.princeton.edu/2014/10/01/eric-avery/

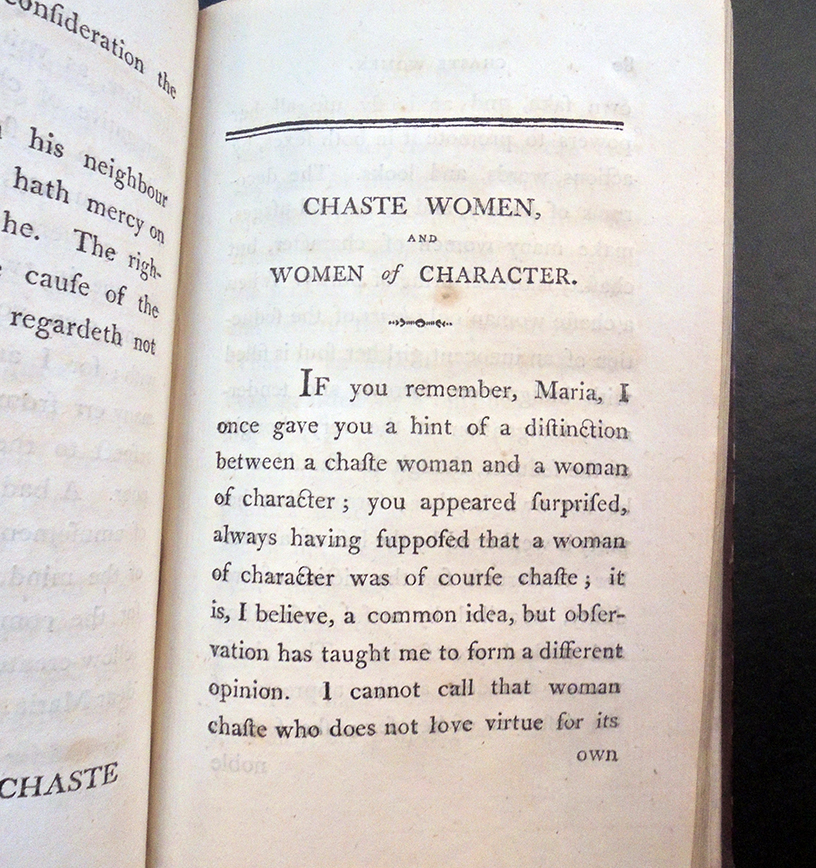

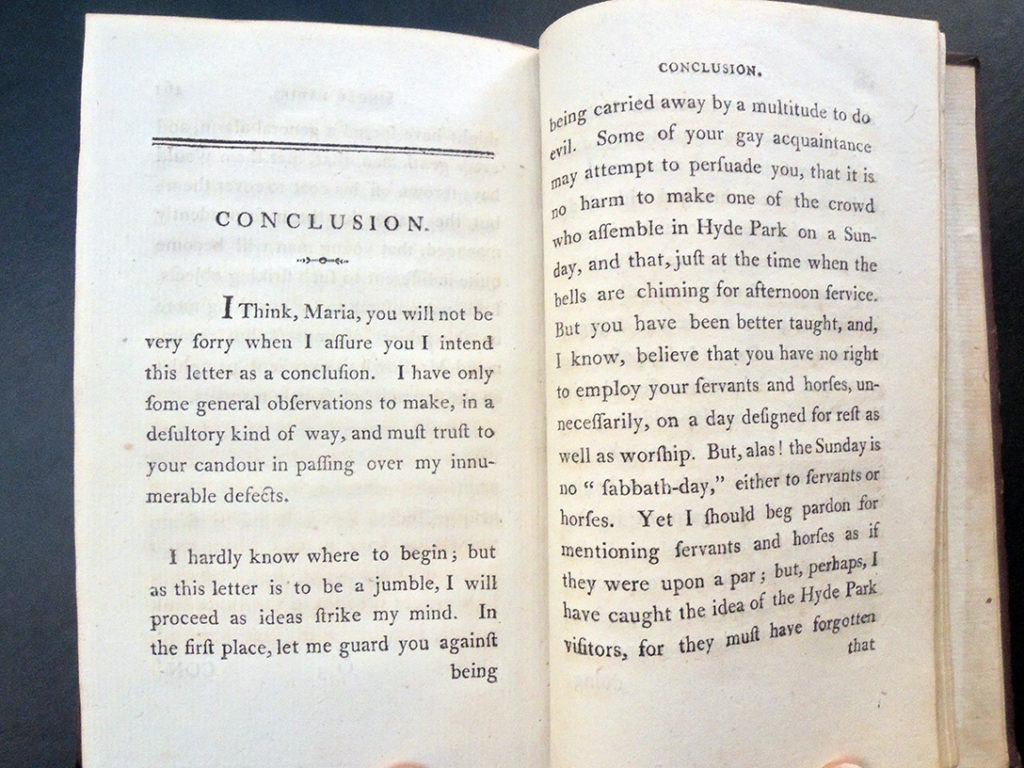

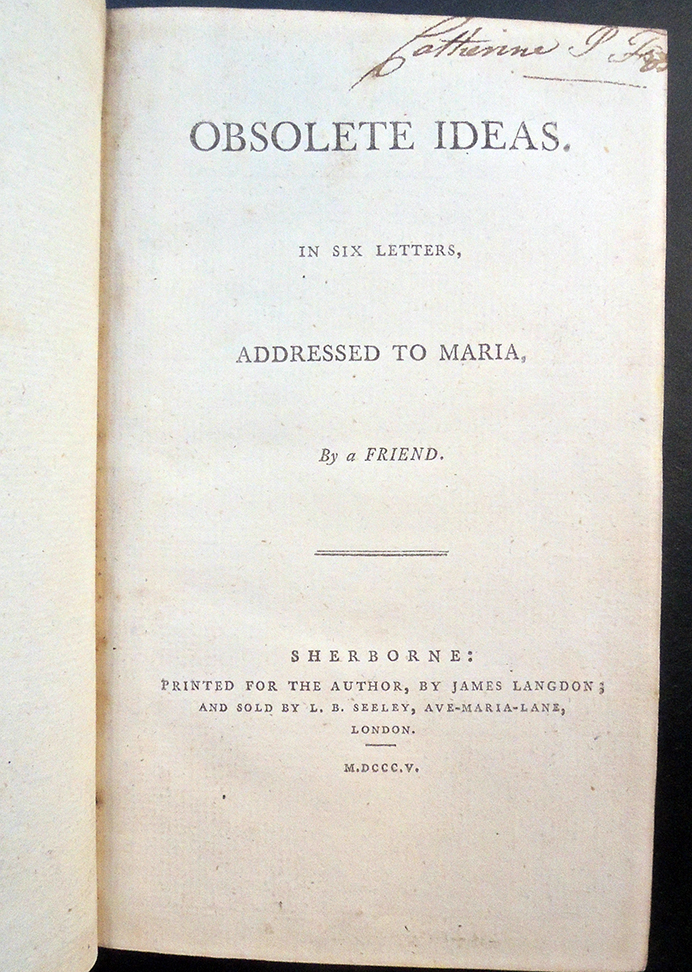

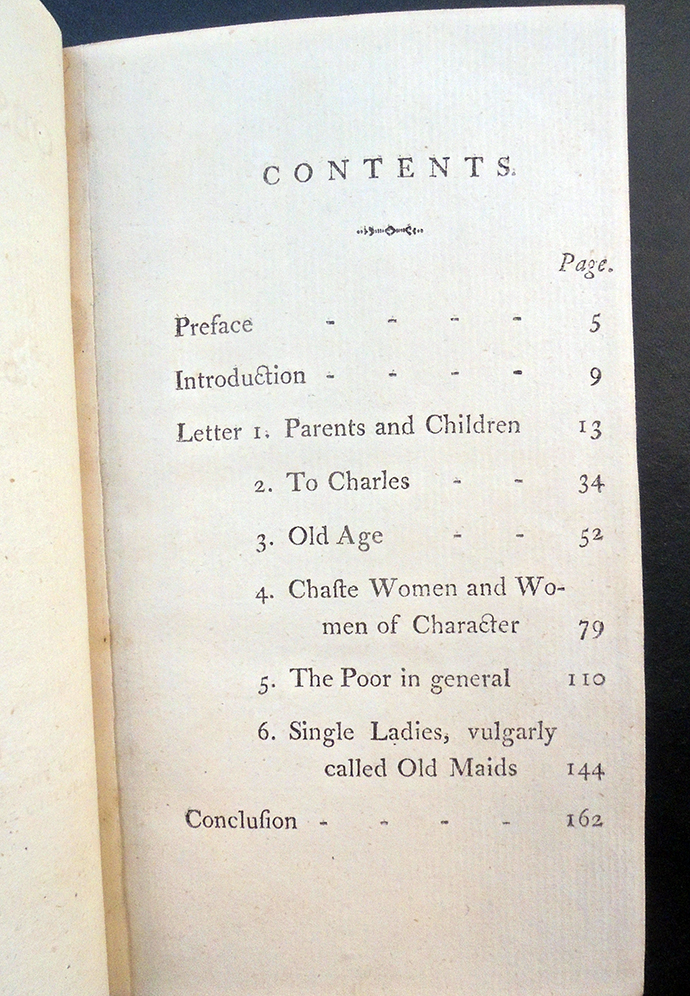

Eliza Browne, Obsolete Ideas, in Six Letters Addressed to Maria By a Friend (Sherborne: for the author by James Langdon, 1805). Graphic Arts Collection GA 2020- in process.

Eliza Browne, Obsolete Ideas, in Six Letters Addressed to Maria By a Friend (Sherborne: for the author by James Langdon, 1805). Graphic Arts Collection GA 2020- in process. The fourth edition of this book introduces yet another women to the mix. It is dedicated to the Viscountess Cremorne, probably Philadelphia Hannah Freame, the daughter of Thomas Freame and Margaretta Penn, fourth daughter of William Penn (1644-1718), the founder of Pennsylvania.

The fourth edition of this book introduces yet another women to the mix. It is dedicated to the Viscountess Cremorne, probably Philadelphia Hannah Freame, the daughter of Thomas Freame and Margaretta Penn, fourth daughter of William Penn (1644-1718), the founder of Pennsylvania. Gilbert Stuart, Portrait of ‘Philadelphia Hannah’, ca. 1785. Oil on canvas. Philadelphia Academy of the Fine Arts 1999.11

Gilbert Stuart, Portrait of ‘Philadelphia Hannah’, ca. 1785. Oil on canvas. Philadelphia Academy of the Fine Arts 1999.11