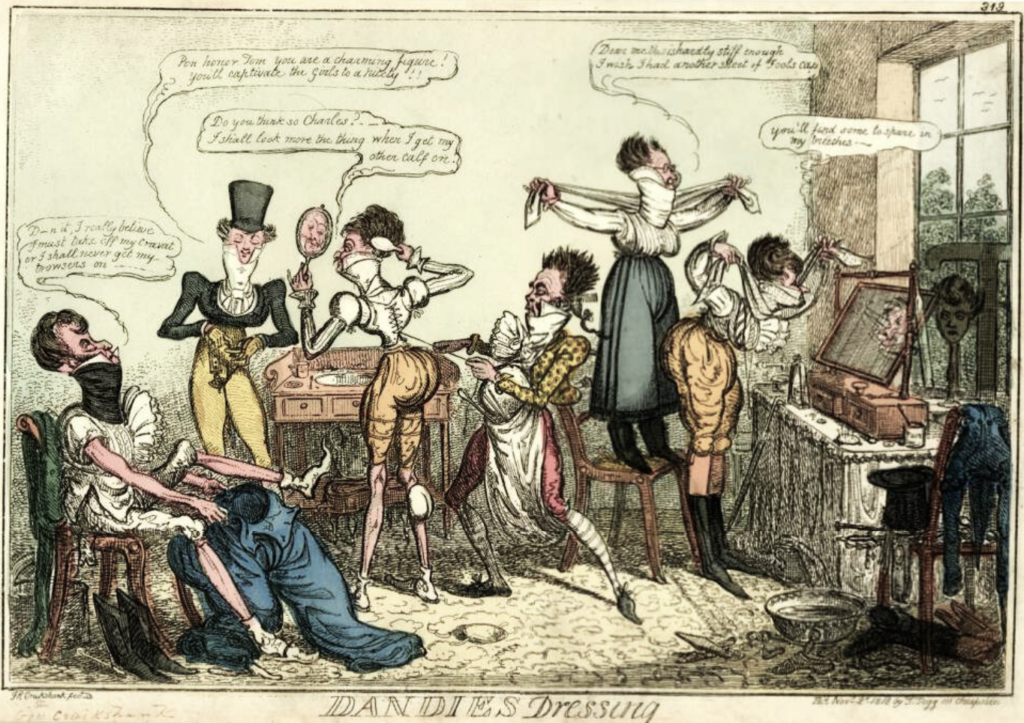

Born to the Manor (Mildenhall, Suffolk), young Henry William Bunbury left St Catharine’s College, Cambridge in 1769 to travel and experience life. From an early age, he showed a talent for drawing and by 1776, Bunbury was exhibiting his work at the Royal Academy. Although he never had much success as a serious painter, his satirical work was enjoyed throughout London. A day job with the army was the inspiration for Bunbury’s humorous books Hints to Bad Horsemen (1781) and An Academy for Grown Horsemen (Princeton has editions 1787, 1788, 1791, 1792, 1796, 1808, 1809, 1825).

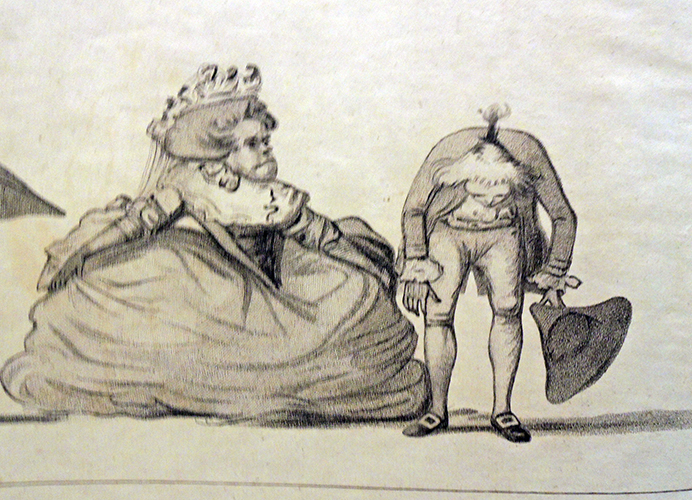

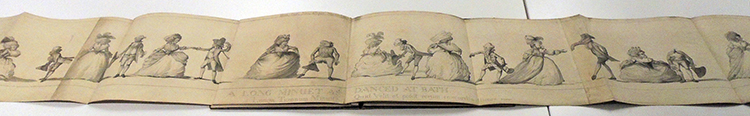

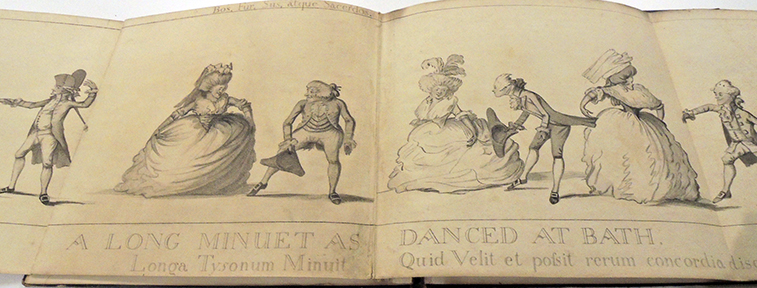

Also around that time, Bunbury drew a series of dancers attempting a minuet, which were pasted together to form a five-foot satirical panorama. The original drawing, now at the Yale Center for British Art, was engraved and published by William Dickinson under the title A Long Minuet as Danced at Bath.

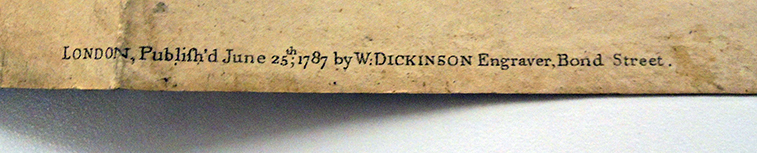

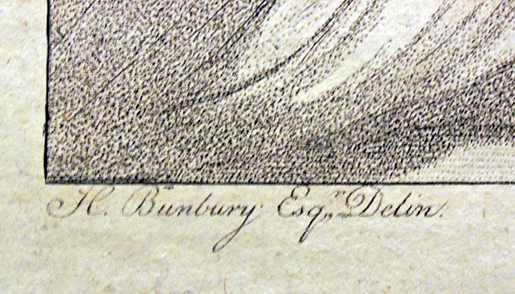

William Dickinson (1746-1823) after Henry William Bunbury (1750-1811), A Long Minuet as Danced at Bath, June 25, 1787. Stipple engraving on four attached plates, approximately 5 feet long. Published by Dickinson, London. Inscribed upper center: “Bos, Fur, Sus atque Sacerdos.”; lower center: “A Long Minuet As Danced At Bath. Longa Tysonum Minuit , Quid velit & possit rerum concordia discors. Horace.” Graphic Arts Collection GAX Oversize Rowlandson 1787.2f

Thanks to the British Museum we know who many of the dancers represent, beginning at the left:

The 1st Mrs Lewis Teissier; much like Anthony Aubert for whom it was done; Miss Vine; The Lord Mair; The Lady Maress; Lord North; Lady Guilford; Monsr Pereg… Bauquier of Paris… 1st Comm… chez Monsr Peuchant [?]; Miss North; Monsieur Pengtcent [?] private envoy to the P. of W. from the King of France; Lady North; Monsieur Grant a Banker at Paris; Miss Dyke; qry [query?] Stephen Teissier; Mrs Laste [?]; qry [query?] Mr. Matthew Purling. my son J Lewis says this however was intended for the Revd. Henry Bate. of turbulent political memory; [unidentified]; [unidentified]; Mrs. Bunbury. Mr. B_s Wife; Tyson – Master of Ceremoni[es].

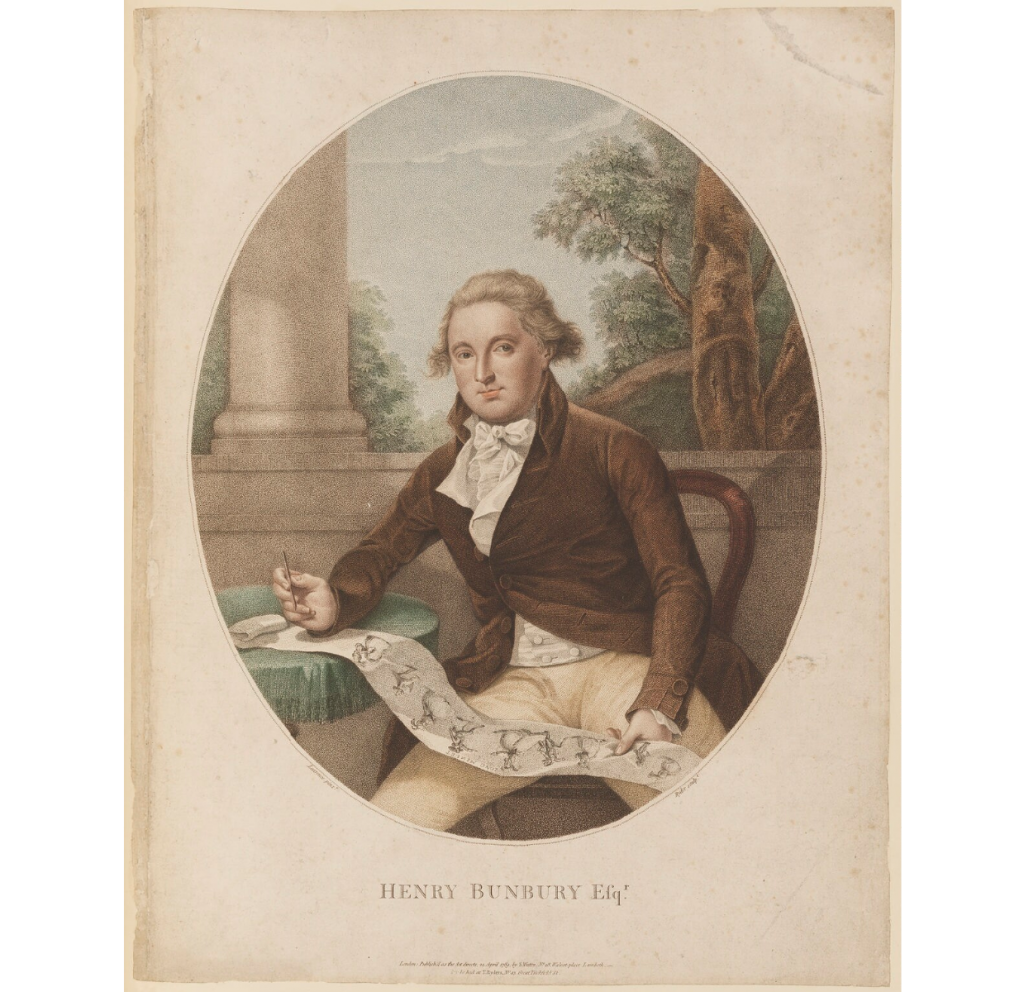

So loved was Bunbury and his humorous work that when he sat for a portrait by Sir Thomas Lawrence (1769-1830), he was asked to pose holding “The Long Minuet.” And if that were not enough, Lawrence’s pastel, now at the National Portrait Gallery, London, was engraved by Thomas Ryder (1746-1810) and distributed by multiple print sellers.

Sir Thomas Lawrence (1769-1830), Henry William Bunbury, ca. 1788. Pastel. National Portrait Gallery, UK 4696

Sir Thomas Lawrence (1769-1830), Henry William Bunbury, ca. 1788. Pastel. National Portrait Gallery, UK 4696

Thomas Ryder (1746-1810) after Sir Thomas Lawrence (1769-1830), Henry William Bunbury Drawing His ‘Long Minuet’, April 24, 1789. Stipple engraving with hand coloring. Published by S. Watts, London. National Portrait Gallery, London, D15022

Thomas Ryder (1746-1810) after Sir Thomas Lawrence (1769-1830), Henry William Bunbury Drawing His ‘Long Minuet’, April 24, 1789. Stipple engraving with hand coloring. Published by S. Watts, London. National Portrait Gallery, London, D15022