South Korean author Han Kang, winner of the Man Booker international prize for her novel The Vegetarian, has been selected as the fifth writer for the Future Library project, conceived and launched by the Scottish artist Katie Paterson in 2014. Each year, one writer is asked to contribute a book, which will not be printed or read for 100 years. A forest of 1,000 Norwegian spruce trees has been planted outside Oslo to provide the paper for these books in 2114.

South Korean author Han Kang, winner of the Man Booker international prize for her novel The Vegetarian, has been selected as the fifth writer for the Future Library project, conceived and launched by the Scottish artist Katie Paterson in 2014. Each year, one writer is asked to contribute a book, which will not be printed or read for 100 years. A forest of 1,000 Norwegian spruce trees has been planted outside Oslo to provide the paper for these books in 2114.

Other authors who have contributed a book to the Future Library are Margaret Atwood, David Mitchell, Turkish novelist Elif Shafak, and Iceland’s Sjón. The Princeton University Library is proud to own a certificate entitling us to one copy of each paper book.

Speaking to the Guardian newspaper, Han said she considered the Future Library to be a project about time. “In Korea, when a couple gets married, people bless them to live together ‘for 100 years’. It sounds like almost an eternity,” she said. “I cannot survive 100 years from now, of course. No one who I love can survive, either. This relentless fact has made me reflect on the essential part of my life. Why do I write? Who am I talking to, when I write?” https://www.theguardian.com/books/2018/aug/31/han-kang-bury-book-100-years-norwegian-forest-future-library

Han will deliver her manuscript, which can be a length of her choosing, to Paterson at a ceremony in the Norwegian forest in May. It will be held in a room in the Deichman library, Oslo, alongside the unpublished and unread manuscripts by Atwood, Mitchell, Shafak and Sjón, until 2114, when it is finally printed.

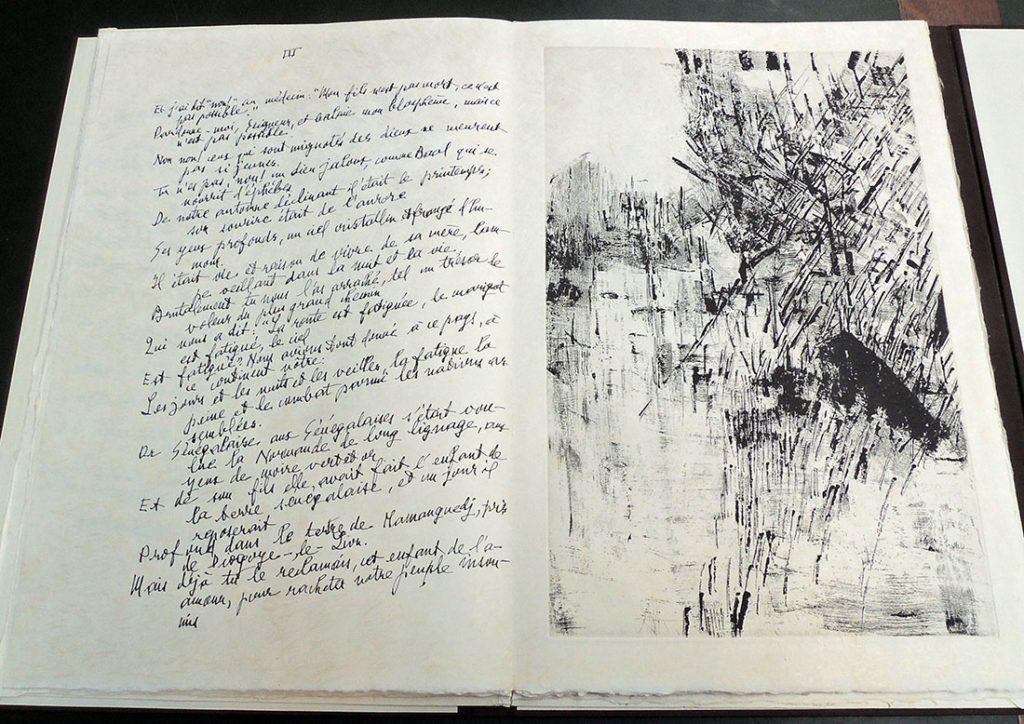

For now, read: Han Kang, The White Book, translated from the Korean by Deborah Smith (London: Portobello Books, 2017). East Asian Library–Western PL992.26.K36 H8413 2017