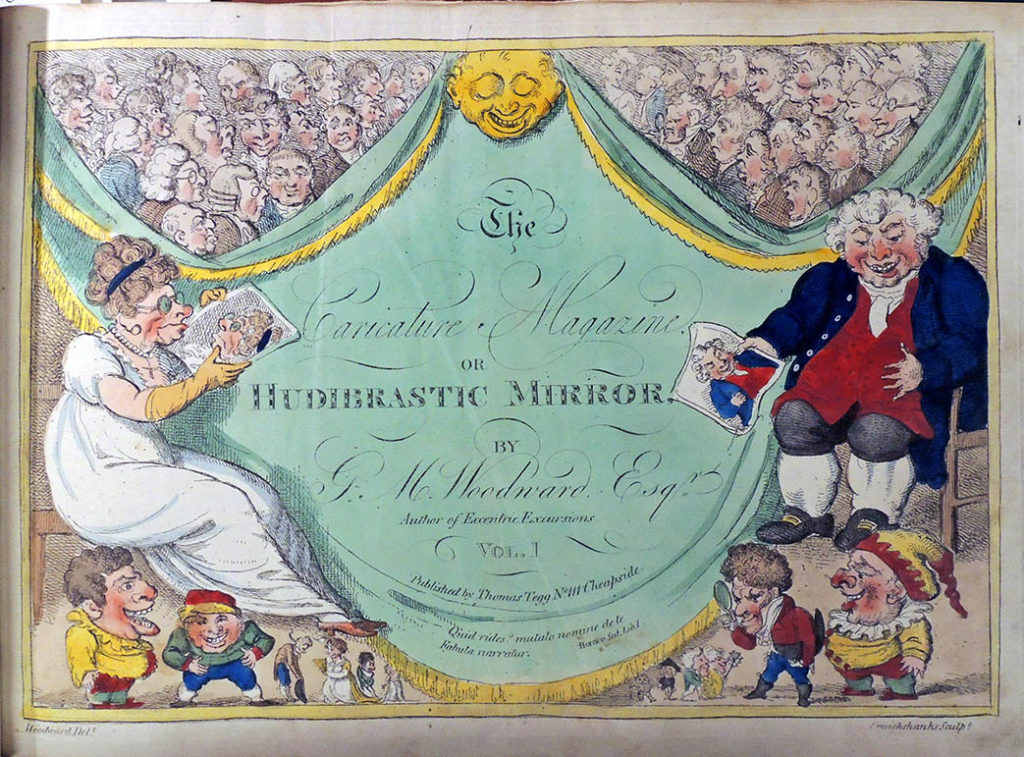

John Syme, John James Audubon (White House)

John Syme, John James Audubon (White House)

January 12, 1861, The Brooklyn Daily Eagle

“The following apocryphal item is going the rounds of the papers:

Among the subscribers to Audubon’s magnificent work on ornithology, the price of which was 1,000 dollars a copy, appeared the name of John Jacob Astor. During the progress of the work, the prosecution of which was exceedingly expensive, M. Audubon, of course, called upon several of his subscribers for payment. It so happened that Mr. Astor (probably that he might not be troubled about small matters) was not applied to before the delivery of the letterpress and plates.

Then, however, Audubon applied for his thousand dollars; but he was put off with one excuse or another. “Ah, M. Audubon,” would the owner of millions observe, “you have come at a bad time; money is very scarce; I have nothing in the bank; I have invested all my funds.”

At length, for a sixth time, Audubon called on Astor for his thousand dollars. As he was ushered into his presence he found Wm. B. Astor, the son, conversing with his father. No sooner did the rich man see the man of art, then he began, “Ah, M. Audubon, so you have come again after your money. Hard times, M. Audubon—money scarce.”

But just then, catching an inquiring look from his son, he changed his tone: “However, M. Audubon, I suppose we must contrive to let you have some of your money if possible. William,” he added, calling to his son, who had walked into an adjoining parlor, “have we any money at all in the bank?”

“Yes, father,” replied the son, supposing that he was asking an earnest question pertinent to what they had been talking of when the ornithologist came in, “we have two hundred and seventy thousand dollars in the Bank of New York, seventy thousand dollars in the City Bank, ninety thousand in the Merchants, ninety-eight thousand four hundred in the Mechanics, eighty three thousand—” “That’ll do, that’ll do,” exclaimed John Jacob, interrupting him; “it seems that William can give a cheque for your money.”

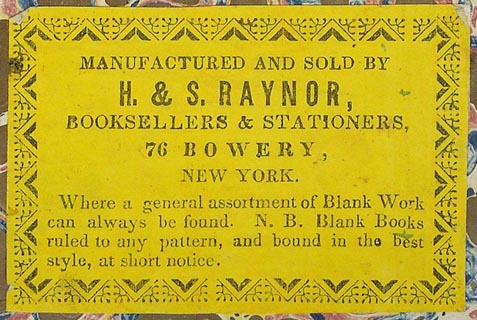

John James Audubon (1785-1851), The Birds of America: from original drawings by John James Audubon … (London: Pub. by the author, 1827-38). Oversize EX 8880.134.11e. The Princeton copy “was presented … in 1927 by Alexander van Rensselaer (Princeton, class of 1871), a charter trustee of the University. It had formerly belonged to Stephen van Rensselaer (Princeton, class of 1808) of Albany, New York, one of the original subscribers to the work. The latter’s name appears as no. 32 in Audubon’s list of subscribers.”