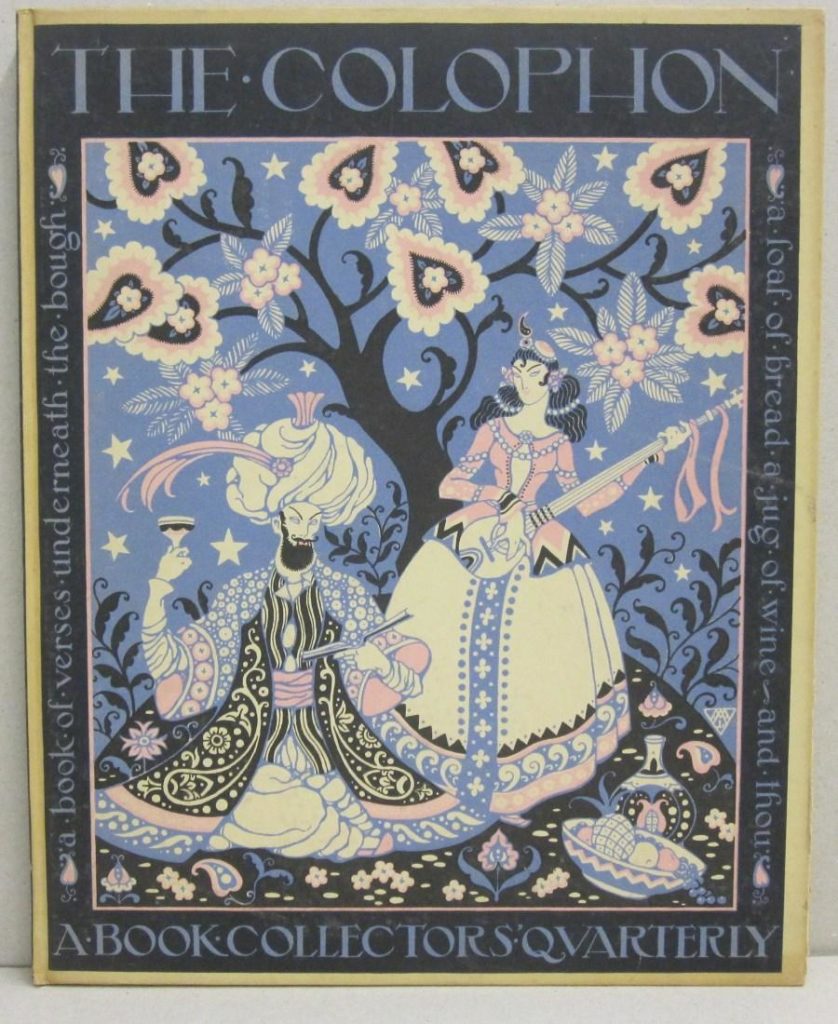

In 1922, bibliophile Elmer Adler (1884–1962) founded the private press Pynson Printers and in 1930, began publishing a quarterly journal for book collectors called The Colophon, which featured articles on publishing, printing, and collecting. The physical volumes were also meant to offer examples of contemporary fine press publishing, with articles designed and printed by various presses within the same issue. The driving forces behind The Colophon were Adler, Burton Emmett, and John T. Winterich along with an extended list of contributing editors named in each issue.

In 1922, bibliophile Elmer Adler (1884–1962) founded the private press Pynson Printers and in 1930, began publishing a quarterly journal for book collectors called The Colophon, which featured articles on publishing, printing, and collecting. The physical volumes were also meant to offer examples of contemporary fine press publishing, with articles designed and printed by various presses within the same issue. The driving forces behind The Colophon were Adler, Burton Emmett, and John T. Winterich along with an extended list of contributing editors named in each issue.

While the vast majority of writers, editors, designers, and printers were men, the publication was not exclusively male and a look at the women who contributed to The Colophon provides insight into the history of the book in America during the early twentieth century. Adler closed Pynson Printers and The Colophon in 1940 when he moved to Princeton University. Although there was an attempt to continue under new editorial leadership, it was never equal to the earlier publication and did not last.

Here are the women included in The Colophon. The attached pdf provides an index to each woman’s individual contributions.The Women of The Colophon

Myrta Lockett Avary (1857-1946), author and journalist. Her books include Dixie After the War, The Recollections of Alexander H. Stephens and Uncle Remus and the Wren’s Nest.

Esther Averill (1902–1992) editor, publisher, writer and illustrator best known for the Cat Club picture books.

Althea Leah (Bierbower) Bass (1892–1988), Western Americana historian. Publications include Young Inquirer, The Arapaho Way, Cherokee Messenger, and The Story of a Young Seneca Indian Girl and Her Family, among others.

Babette Ann Boleman (1900s), author and rare book researcher.

Pearl S. Buck (1892–1973), writer and novelist. As the daughter of missionaries, Buck spent most of her life before 1934 in Zhenjiang, China. Her novel The Good Earth was the best-selling fiction book in the United States in 1931 and 1932 and won the Pulitzer Prize in 1932.

Willa Cather (1873–1947), writer and novelist. Notable books on American frontier life include O Pioneers!, The Song of the Lark, and My Ántonia. Elmer Adler and Pynson Printers published her early poetry.

Bertha Coolidge (1880–1953) American portrait miniaturist and bibliographer. Notable compilations include Morris L. Parrish’s A List of the Writings of Lewis Carroll [Charles L. Dodgson]in the Library at Dormy House, Pine Valley, New Jersey (1928) and A Catalogue of the Altschul Collection of George Meredith in the Yale University Library (1931).

Bertha Jean Cunningham (1900s), author, married to a book collector living in Chicago.

Anne Goldthwaite (1869–1944), painter. Trained in Paris, Goldthwaite returned to New York in time to be included in the 1913 Armory Show. She was close friends of Kathrine Dreier, Edith Halpert, and Joseph Brummer, who each exhibited and sold her work at various stages of her career. She was also an active member of the New York Society of Women Artists and enthusiastic advocate for women’s rights.

Belle da Costa Greene (1883–1950), librarian to J. P. Morgan. After his death in 1913, Greene continued as librarian under his son, Jack Morgan. In 1924 the private collection was incorporated by the State of New York as a library for public uses and the Board of Trustees appointed Greene first director of the Pierpont Morgan Library.

Ruth Shepard Granniss (1872–1954), librarian to The Grolier Club, New York. Author of The Book in America, in collaboration with Lawrence C. Wroth, John Carter Brown Library (1939).

Jeanette Griffith (active 1920s–1930s), photographer.

Anne Lyon Haight (1895-1977), writer and bibliophile. Her books include Banned books, Notes on Some Books Banned for Various Reasons at Various Times and in Various Places; Morals, Manners, Etiquette and the Three R’s; and Portrait of Latin America as Seen by her Print Makers. Most notably, she was President of the Hroswitha Club, a women’s bibliophilic organization.

Helen O’Connor Harter (1905–1990), artist and illustrator. Married Thomas Harter, chief of the Los Angeles Examiner’s art department, and moved to New York City where they both worked as commercial illustrators. Eventually, they settled in Helen’s hometown of Tempe, Arizona, where she continued to teach and paint.

Victoria Hutson Huntley (1900–1971), artist and printmaker. Hutson studied under John Sloan and Max Weber, specializing in lithography and awarded prizes from the Chicago Art Institute and the Philadelphia Print Club. She painted murals for the post office in Greenwich, Connecticut, and in Springville, New York, under the Treasury Relief Art Project, part of the New Deal arts program.

Helen M. Knubel (1901-1992), historian. According to the New York Times, she was considered the foremost archivist of the history of the Lutheran Church in North America. She helped to organize the library and archives of the National Lutheran Council, of which she was the secretary of research and statistics from 1954 to 1966. She then became associate director of the Office of Research, Statistics and Archives of the Lutheran Council in the U.S.A., the successor of the NLC.

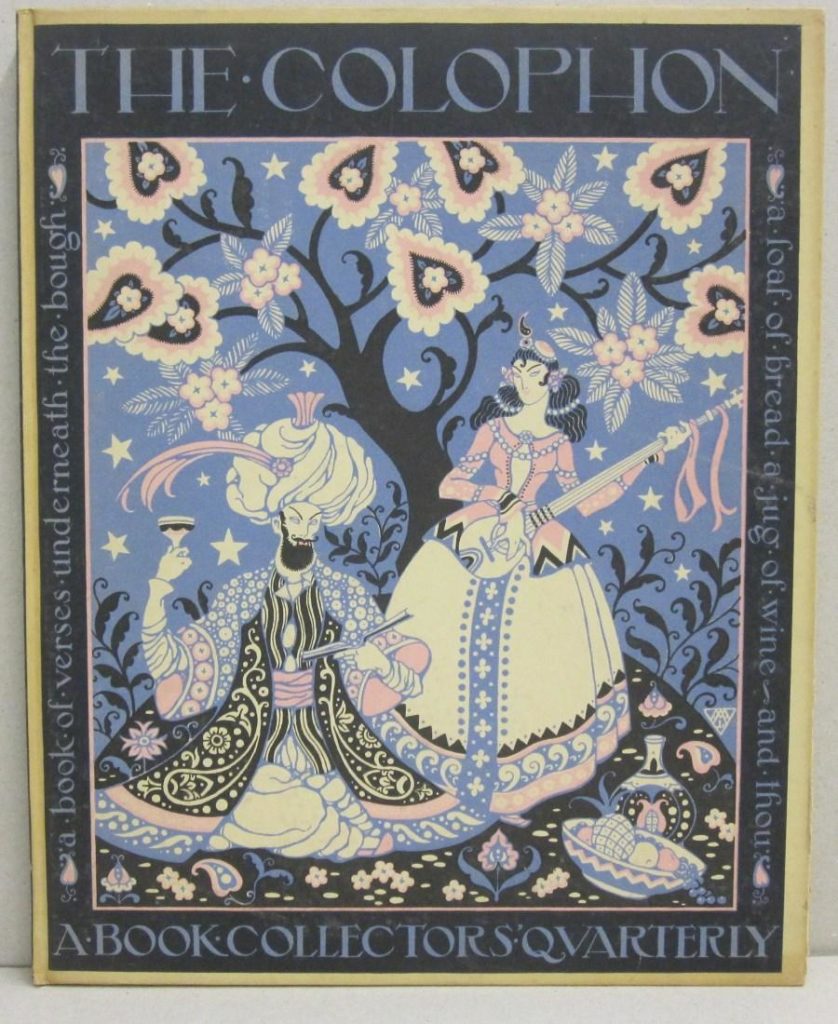

Marie Abrams Lawson (1894–1956), author and illustrator. The only woman asked to design a cover of The Colophon, Lawson primarily wrote and illustrated children’s books. She was married to Robert Lawson, also a children’s book author and illustrator.

Vera Liebert (1900s), actress and theater historian.

Flora Virginia Milner Livingston (1862–1962), librarian and bibliographer. She was named curator of Harry Elkins Widener collection at Harvard College Library, following the death of her husband Luther S. Livingston, the first librarian of the Widener collection. She completed bibliographies for Rudyard Kipling, Henry James, John Gay and others.

(Emma) Miriam Lone (born ca. 1873), bibliographer and chief cataloguer for New York dealer Lathrop Harper. Author of A Selection of Incunabula Describing One Thousand Books Printed in the XVth Century.

Dorothy McEntee (1902-1990) artist and printmaker.

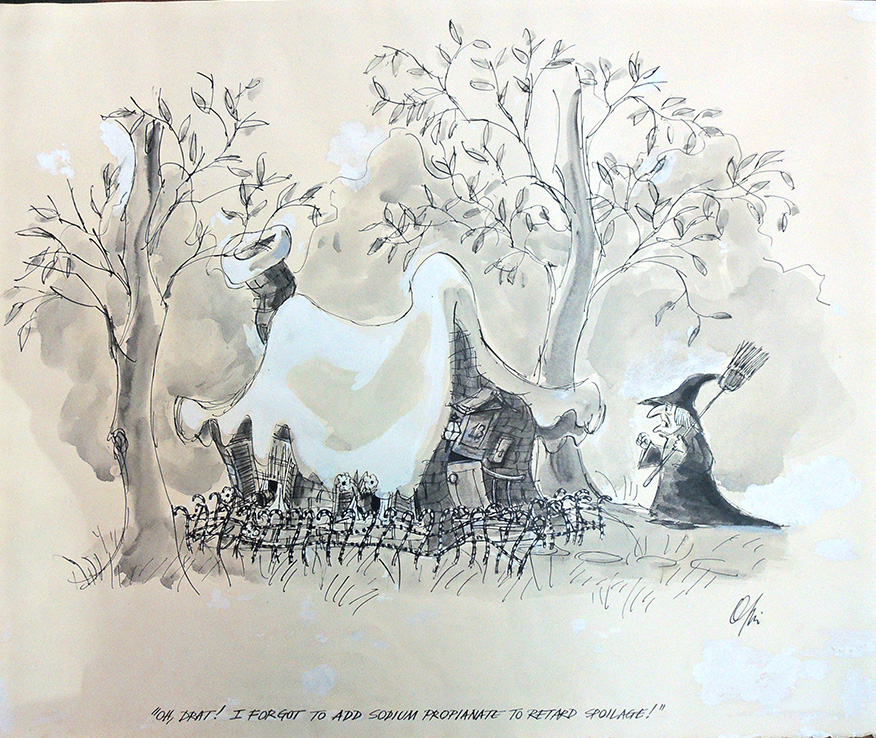

Dorothy McKay (1902–1972), artist and cartoonist. McKay drew for various magazines including The New Yorker, Esquire, and Life, among others.

Edith Whittlesley Newton (1878–1964), painter and printmaker. Newton lived in New Milford, Connecticut, where she specialized in landscape painting and lithographs.

Lucy Eugenia Osborne (1879–1955), librarian, bibliographer, and historian of rare books at the Chapin Library, Williams College from 1922 to 1947.

Elizabeth Robins Pennell (1855–1936), American writer. She wrote art criticism, travelogues, memoirs, and biographies of Mary Wollstonecraft, Charles Godfrey Leland, and James Abbott McNeill Whistler. She was also a collector of cookbooks, which was given to the Library of Congress along with her husband, Joseph Pennell’s library.

Carlotta Petrina (1901–1997), artist and printer. Best known for her 1933 illustrations to John Milton’s Paradise Lost and the John Dryden translation of Virgil’s Aeneid (1944). The Carlotta Petrina Museum and Cultural Center in Brownsville, Texas, exhibits her art and memorabilia.

Fanny (Fannie Elizabeth) Ratchford (1887–1974), librarian and historian. Ratchford served as librarian of rare books at the University of Texas, Austin. She wrote numerous books and articles, beginning with Some Reminiscences of Persons and Incidents of the Civil War (1909). She received Guggenheim fellowships for 1929–1930, 1939–1940, and 1957–1958 and, late in life, assisted in editing the Oxford edition of the complete works of the Brontës.

Elizabeth Ridgway (1900s), book collector.

Ethel Dane Roberts (1900s), librarian and curator of the Frances Pearsons Plimpton Library of Italian Literature, Wellesley College, Wellesley, Massachusetts.

Dorothy Leigh Sayers (1893–1957), English crime writer, poet, playwright, and humanist. Best known for her mysteries, especially the character of amateur sleuth Lord Peter Wimsey.

Lillian Gary Taylor (1865–1961), collector. Taylor’s library of best-selling American fiction included over 1900 volumes published between 1787 and 1945 and was donated to the University of Virginia in 1945.

Eleanor M. Tilton (1913-1991?), professor and authority on Ralph W. Emerson.

Olivia H. D. Torrence (1900s), author and wife of the poet Ridgely Torrence.

Janet Camp Buck Troxell (1897–1987), collector. Between 1930 and 1965 she amassed over 800 printed items and more than 3,000 manuscripts relating to the Rossettis and their friends (now at Princeton University Library). Names relate to three marriages: Wilder Hobson, New York publisher; Dr. Albert W. Buck, superintendent of New Haven Hospital; and Gilbert McCoy Troxell, curator of American literature, Yale University Library.

Eunice Wead (1881–1969), librarian and curator. A graduate of Smith College, Wead became Smith’s reference librarian in 1906. She moved to Ann Arbor, Michigan, serving as a curator of rare books in the general library, in the William L. Clements Library, and as one of the first teachers in the Department of Library Science. On her retirement from Michigan, she returned to Smith to give a course in book history and book arts.

Carolyn Wells (1862–1942), writer and collector. Wells was a prolific author, including mystery novels, poetry, humor, and children’s books. Her collection of Walt Whitman poetry was donated to the Library of Congress.

Blanche Colton Williams (1879–1944) author and professor of English literature. Williams earned a master’s degree from Columbia University in 1908 and a doctorate in 1913. She went on to teach in the English Department at Hunter College and eventually head of the department. The first editor of the O. Henry Prize Stories, she also collected George Eliot first editions, donated to the Mississippi University for Women library.

Edith Wharton (1862–1937), novelist and playwright. Wharton was the first woman to win the Pulitzer Prize for Literature in 1921. She is best remembered for her books The Age of Innocence, The House of Mirth, Ethan Frome, and her manual The Writing of Fiction.

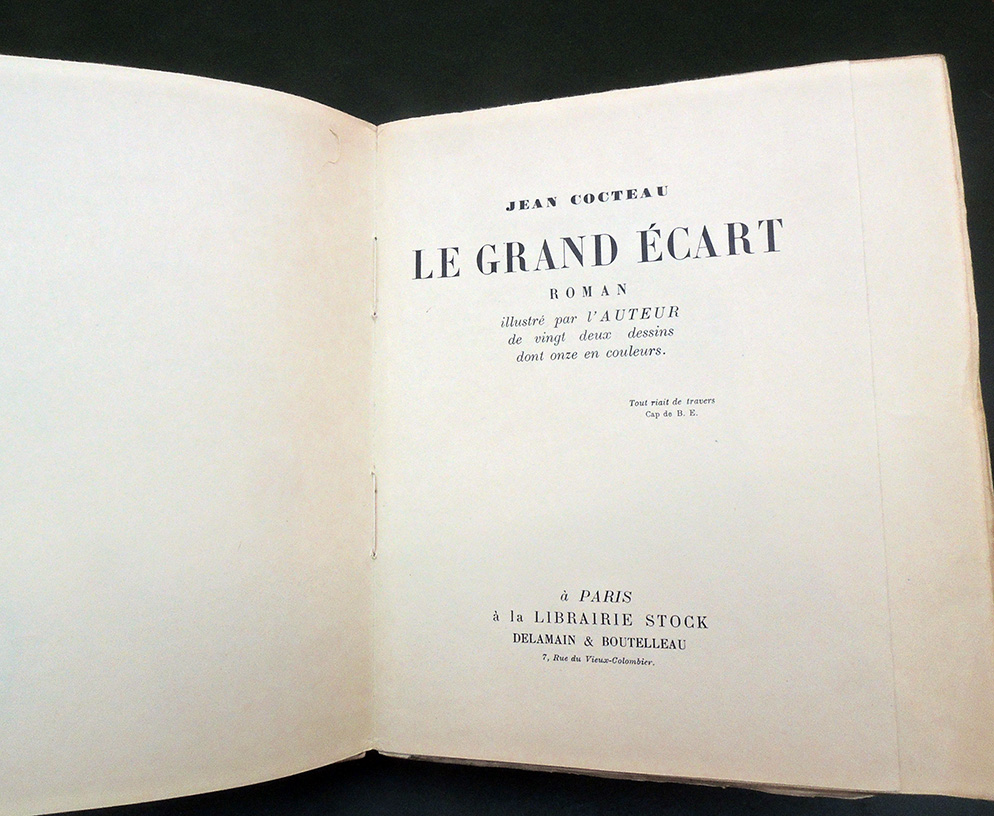

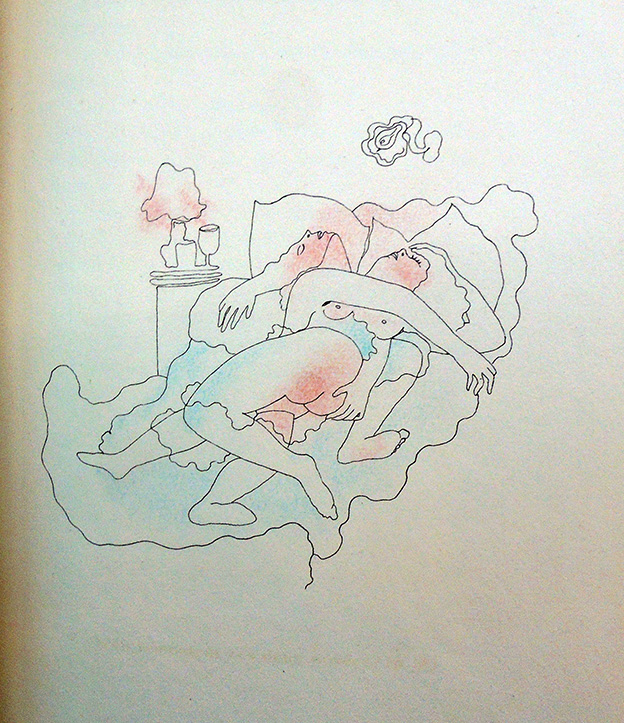

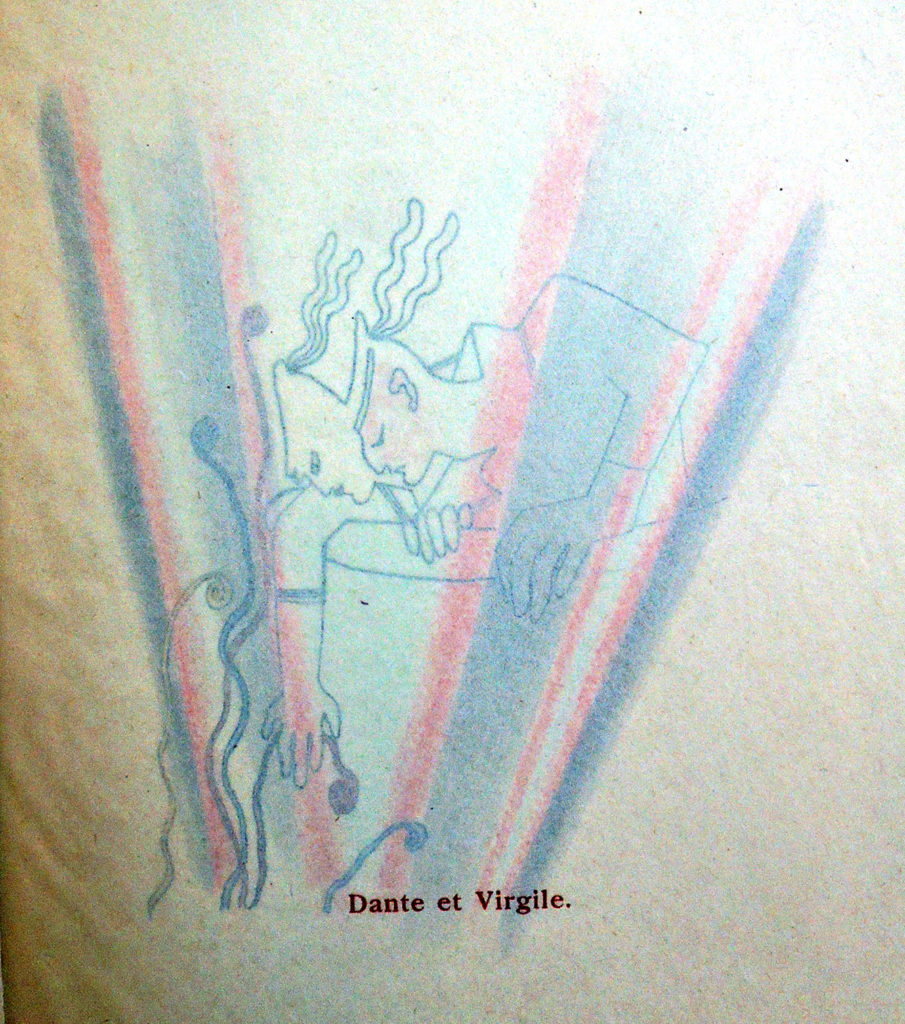

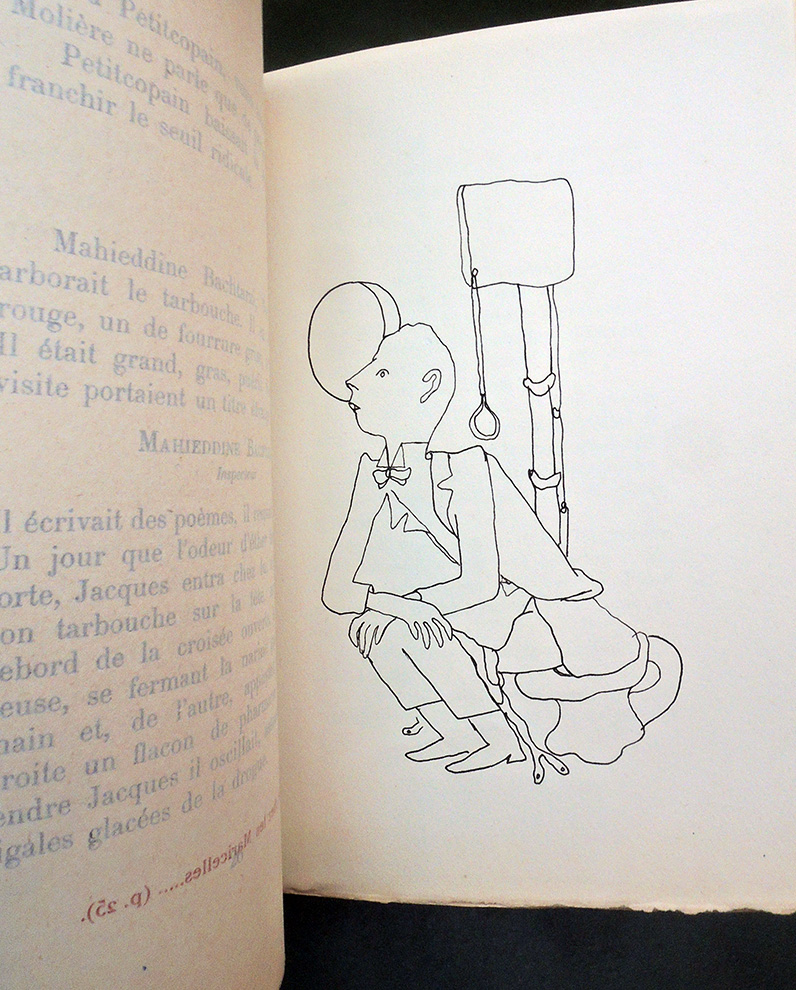

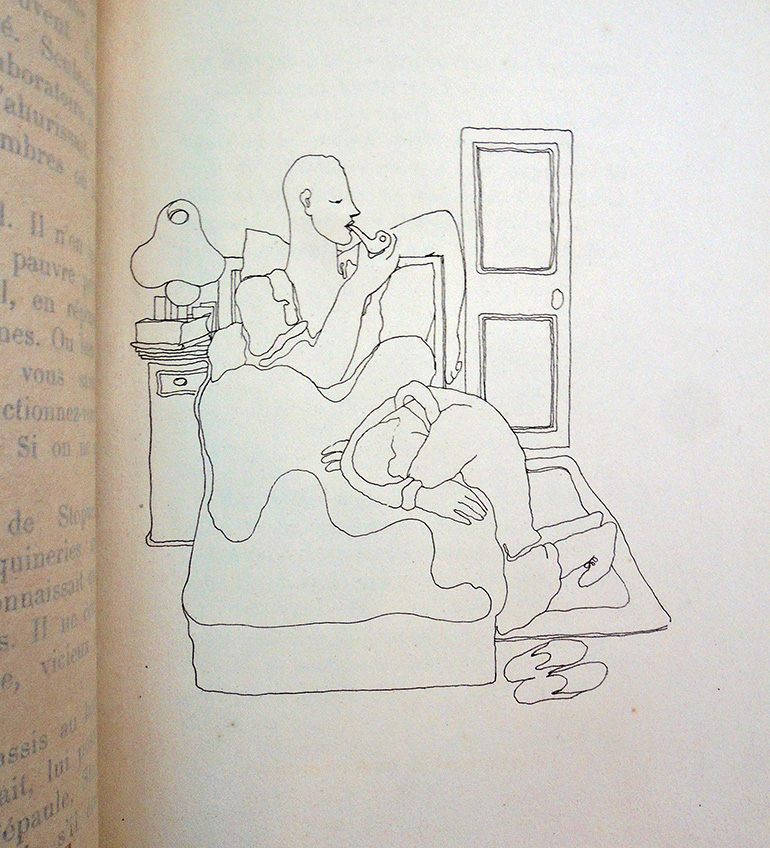

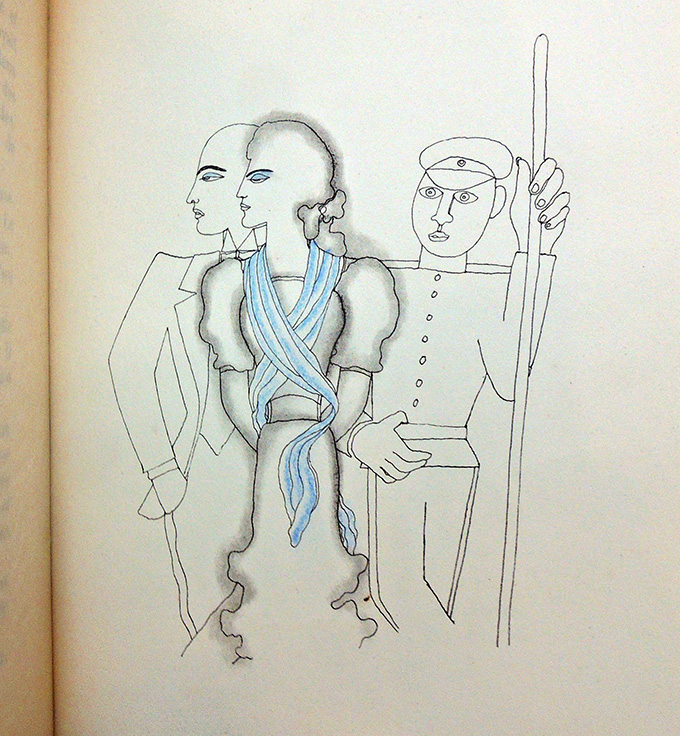

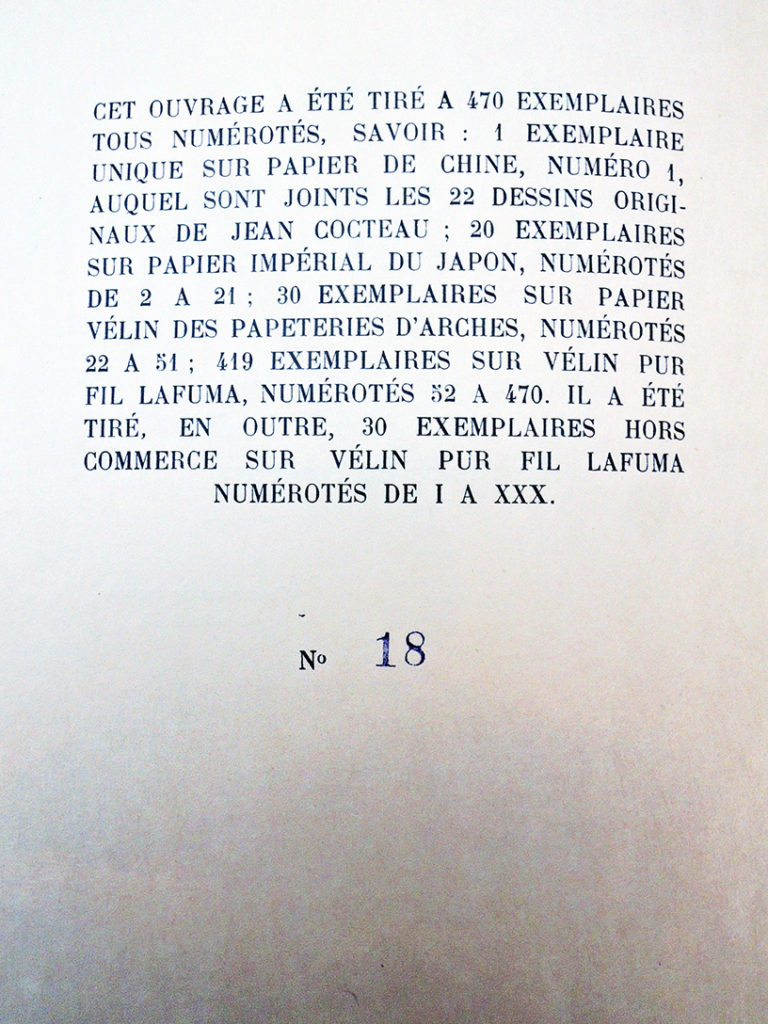

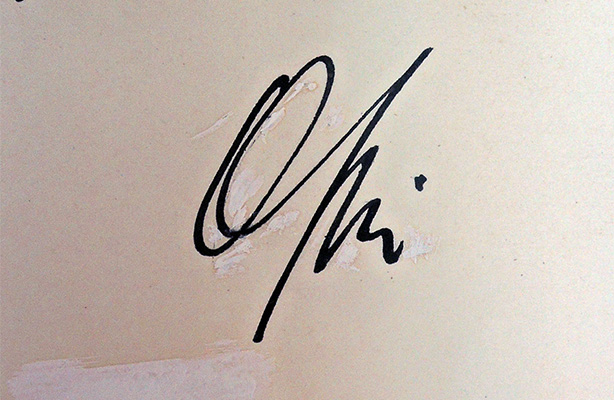

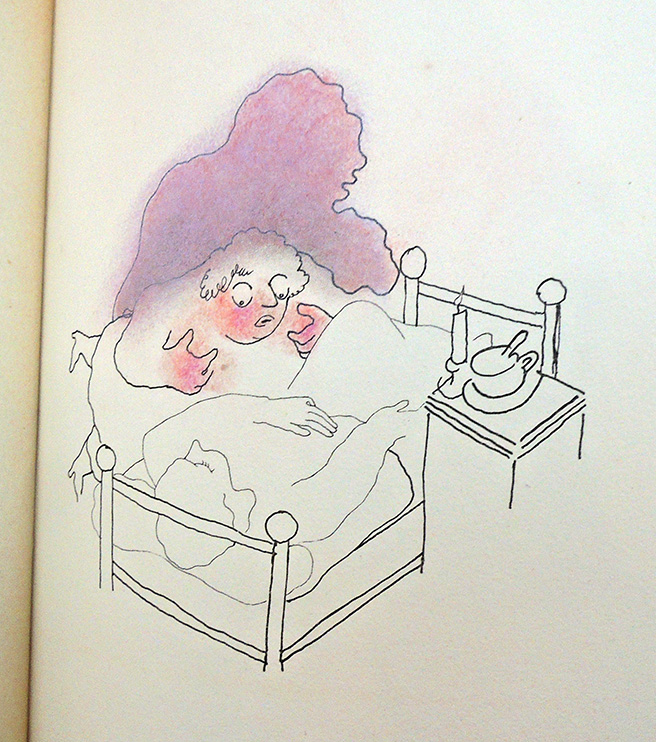

Jean Cocteau (1889-1963). Le Grand Ecart. Roman illustré par l’auteur de vingt deux dessins dont onze en couleurs (Paris: Librairie Stock, 1926). First illustrated edition, with reproductions of 22 drawings by Cocteau, 11 in color. Copy 18 of 20 on imperial Japan paper. A fine inscribed copy with a large original drawing by Jean Cocteau (profile of a male head): “à Parisot Souvenir très amical de Jean Cocteau.” Graphic Arts Collection GAX 2019- in process

Jean Cocteau (1889-1963). Le Grand Ecart. Roman illustré par l’auteur de vingt deux dessins dont onze en couleurs (Paris: Librairie Stock, 1926). First illustrated edition, with reproductions of 22 drawings by Cocteau, 11 in color. Copy 18 of 20 on imperial Japan paper. A fine inscribed copy with a large original drawing by Jean Cocteau (profile of a male head): “à Parisot Souvenir très amical de Jean Cocteau.” Graphic Arts Collection GAX 2019- in process