Crispijn van den Queborn (1604-1652) after Isaac Oliver (ca.1556-1617), Elisabet D.G. Angliae Franciae, et Hiberniae, Regina, 1625. Engraving. Graphic Arts Collection

Crispijn van den Queborn (1604-1652) after Isaac Oliver (ca.1556-1617), Elisabet D.G. Angliae Franciae, et Hiberniae, Regina, 1625. Engraving. Graphic Arts Collection

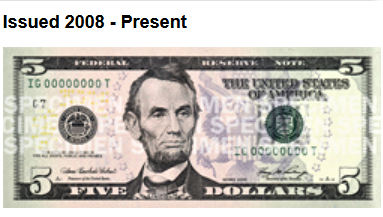

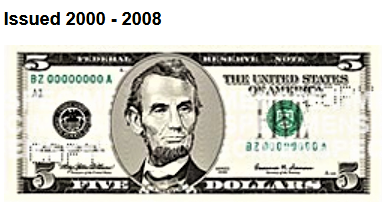

It was not difficult to identify this engraving of Elizabeth I, Queen of England (1533–1603), with the information inscribed on the plate below image: “Mortua Anno MiserI CorDI ae At 70 / Crisp: van queboren Sculp A:1625”

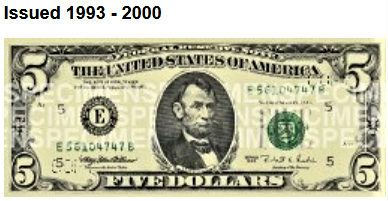

The half-length posthumous portrait shows Elizabeth I wearing an elaborate pearl adorned dress with a striking ruff and crown. According to O’Donoghue’s A Descriptive and Classified Catalogue of Portraits of Queen Elizabeth (1894): “It is a noteworthy fact that none of the engravings of Elizabeth published in or near her own time can be affiliated to existing oil paintings or miniatures, and (with the exception of the large plate by C. van de Passe and one of those by F. Delaram), none bear the name of the original artist.”

O’Donoghue continues “The most striking of all, and one peculiarly associated with Elizabeth, is the ruff, and almost the entire history of the rise and progress of that remarkable article of attire may be traced in her portraits; for this reason the various forms which it took at different periods have been used for the classification of the present catalogue.”

When researching the fashion of Elizabethan London, one of the first contemporaneous sources is Philips Stubbes’ The anatomie of abuses, published in 1583 and reprinted four times over the course of the next decade. While documenting both men and women’s dress, Stubbes did not hesitate to give his opinions, subtitling his study: “a discouerie, or briefe summarie of such notable vices and imperfections, as now raigne in many countreyes of the world: but (especiallye) in a famous ilande called Ailgna: together, with most fearefull examples of Gods iudgements, executed vppon the wicked for the same, aswel in Ailgna of late, as in other places, elsewhere. Very godly, to be reade of all true Christians: but most needefull to be regarded in Englande. Made dialogue-wise by Phillip Stubbes. Here is a segment on Ruffes:

They have great and monsterous ruffes, made either of Camericke, Holland, Lawne, or els of some other the finest cloth that can be got for money, whereof some be a quarter of a yard deep, yea, some more, very few lesse; So that they stand a full quarter of a yarde (and more) from their necks, hanging over their shoulder poynts, instead of a vaile. But if Aeolus with his blasts, or Neptune with his stormes chaunce to hit uppon the crafie bark of their brused ruffes, then they goe flip flap in the winde, like rags flying abroad, and lye upon their shoulders like the dishcloute of a slut. But wot you what? The devil, as he in the fulnes of his malice, first invented these great ruffes, so hath hee now found out also two great stayes to beare up and maintaine that his kingdome of great ruffs : the one arch or piller wherby his kingdome of great ruffes is underpropped, is a certaine kinde of liquide matter which they call Starch, wherin the devill hath willed them to wash and dive his ruffes wel, which when they be dry, wil then stand stiffe and inflexible about their necks. The other piller is a certain device made of wyers, crested for the purpose, whipped over either with gold, thred, silver or silk, and this hee calleth a supportasse, or underpropper. This is to be applyed round about their necks under the ruffe, upon the out side of the band, to beare up the whole frame and body of the ruffe from falling and hanging down….

So few have them, as almost none is without them; for every one, how meane or simple soever they bee otherwise, will have of them three or foure apeece for sayling. And as though Cambrick, Holland, Lawne, and the finest cloth that maye bee got any where for money, were not good inough, they have them wrought all over with silke woorke, and peradventure laced with golde and silver, or other costly lace of no small price. And whether they have Argente to mayntaine this geare withall, or not, it forceth not much, for they will have it by one meane or another, or else they will eyther sell or morgage their Landes (as they have good store) on Suters hill & Stangate hole, with losse of their lives at Tiburne in a rope. & in sure token thereof, they have now newly found out a more monstrous kind of ruffe of xii. (12) , yea, xvi (16) lengthes a peece, set 3 or 4 times double, & is of some, fitlie called: “Three steppes and a halfe to the Gallowes”.

The women there [in Ailgna] use great ruffes, & neckerchers of holland, lawne, camerick, and such cloth, as the greatest thred shall not be so bigge as the least haire that is: then, least they should fall down, they are smeared and starched in the devils liquore, I meane Starch: after that, dryed with great diligence, streaked, patted and rubbed very nicely, and so applyed to their goodly necks, and, withall, underpropped with supportasses (as I tolde you before) the stately arches of pride: beyond all this they have a further fetch, nothing inferiour to the rest; as, namely, three or foure degrees of minor ruffes, placed gradatim, step by step, one beneath the other, and all under the Maister devil ruffe. The skyrts, then, of these great ruffes are long and wide every way, pleted and crested ful curiously, God wot. Then, last of all, they are either clogged with golde, silver, or silk lace of stately price, wrought all over with needle woork, speckled and sparkled heer and there with the sonne, the moone, the starres, and many other antiquities straunge to beholde. Some are wrought with open woork down to the midst of the ruffe and further, some with purled lace so cloyd, and other gewgawes so pestered, as the ruffe is the least parte of it self. Sometimes they are pinned up to their eares, sometimes they are suffered to hang over their shoulders, like windmil sayles fluttering in the winde; and thus every one pleaseth her self with her foolish devices, for suus cuiusque crepitus sibi bene olet, as the proverb saith: “every one thinketh his own wayes best”.

The women there [in Ailgna] use great ruffes, & neckerchers of holland, lawne, camerick, and such cloth, as the greatest thred shall not be so bigge as the least haire that is: then, least they should fall down, they are smeared and starched in the devils liquore, I meane Starch: after that, dryed with great diligence, streaked, patted and rubbed very nicely, and so applyed to their goodly necks, and, withall, underpropped with supportasses (as I tolde you before) the stately arches of pride: beyond all this they have a further fetch, nothing inferiour to the rest; as, namely, three or foure degrees of minor ruffes, placed gradatim, step by step, one beneath the other, and all under the Maister devil ruffe. The skyrts, then, of these great ruffes are long and wide every way, pleted and crested ful curiously, God wot. Then, last of all, they are either clogged with golde, silver, or silk lace of stately price, wrought all over with needle woork, speckled and sparkled heer and there with the sonne, the moone, the starres, and many other antiquities straunge to beholde. Some are wrought with open woork down to the midst of the ruffe and further, some with purled lace so cloyd, and other gewgawes so pestered, as the ruffe is the least parte of it self. Sometimes they are pinned up to their eares, sometimes they are suffered to hang over their shoulders, like windmil sayles fluttering in the winde; and thus every one pleaseth her self with her foolish devices, for suus cuiusque crepitus sibi bene olet, as the proverb saith: “every one thinketh his own wayes best”.

Seen above:

Francis Delaram. From Annales: The True and Royal History, of the Famous Empresse Elizabeth, Queene of England, France and Ireland, &c., by William Camden. 1625.

The Ermine Portrait [Elizabeth I] by Nicholas Hilliard (1585).

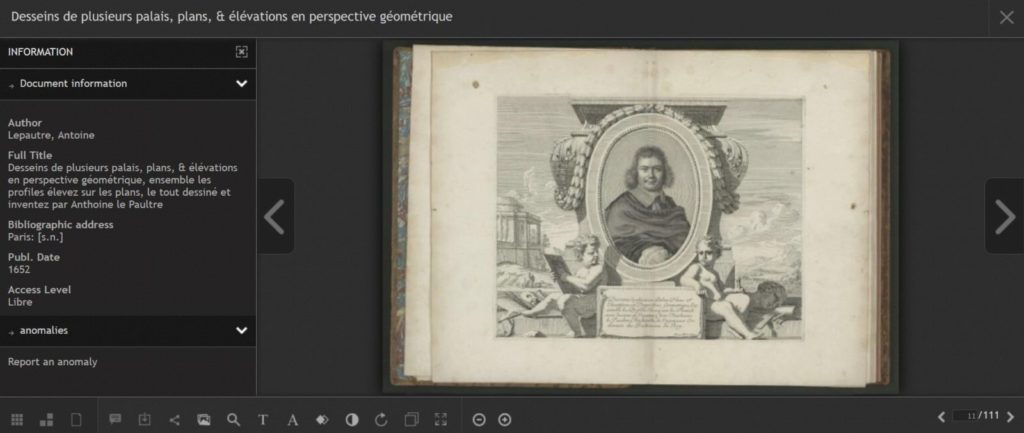

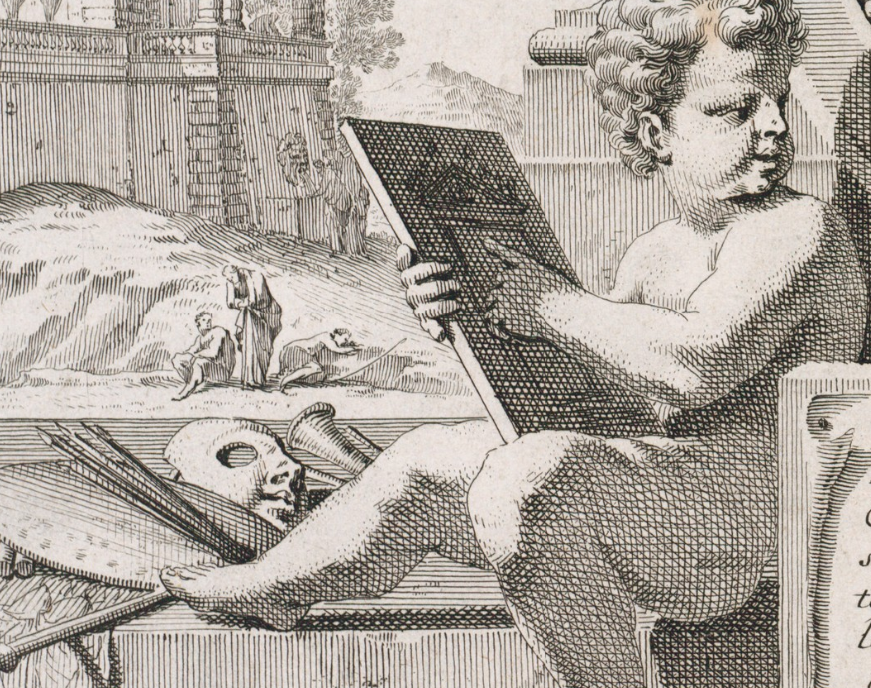

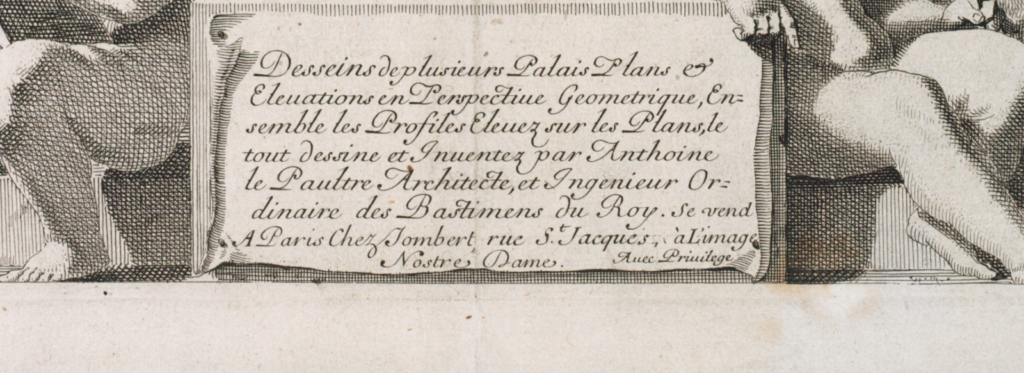

Robert Nanteuil (1623-1678), Antoine Le Pautre, architecte et ingenieur, 1652. Engraving. Graphic Arts Collection 2005.01080. Dumesnil no. 127. Gift of John Douglas Gordon, Class of 1905. Permanent Link: http://arks.princeton.edu/ark:/88435/r781wg115

Robert Nanteuil (1623-1678), Antoine Le Pautre, architecte et ingenieur, 1652. Engraving. Graphic Arts Collection 2005.01080. Dumesnil no. 127. Gift of John Douglas Gordon, Class of 1905. Permanent Link: http://arks.princeton.edu/ark:/88435/r781wg115