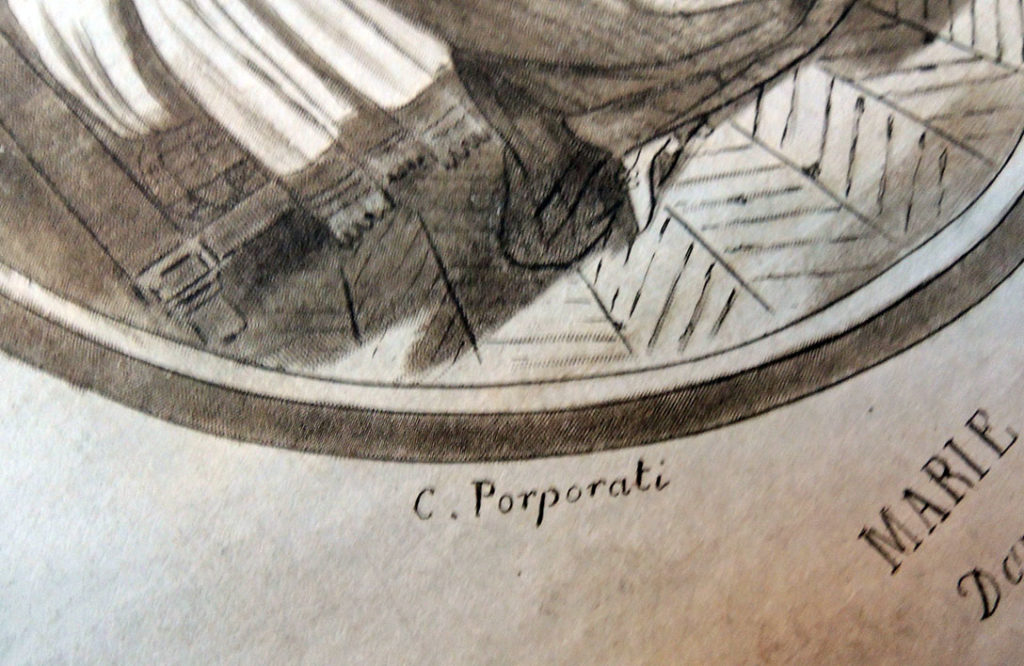

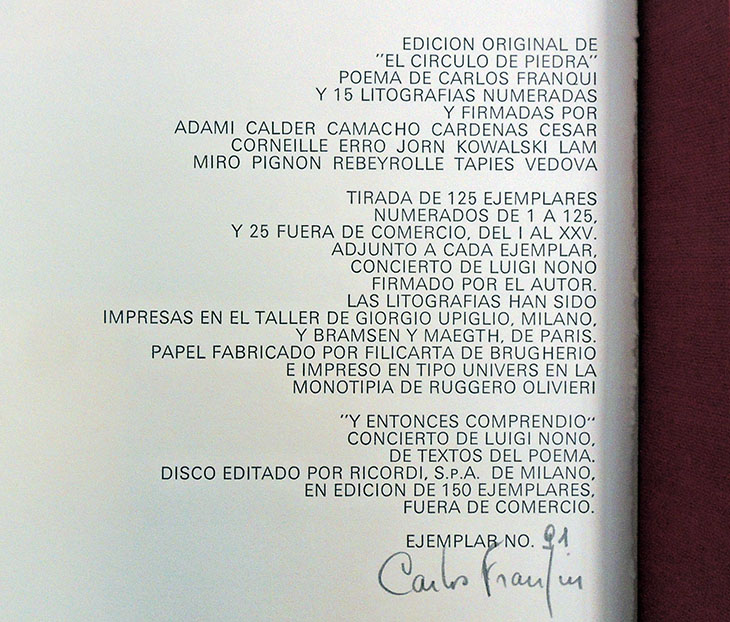

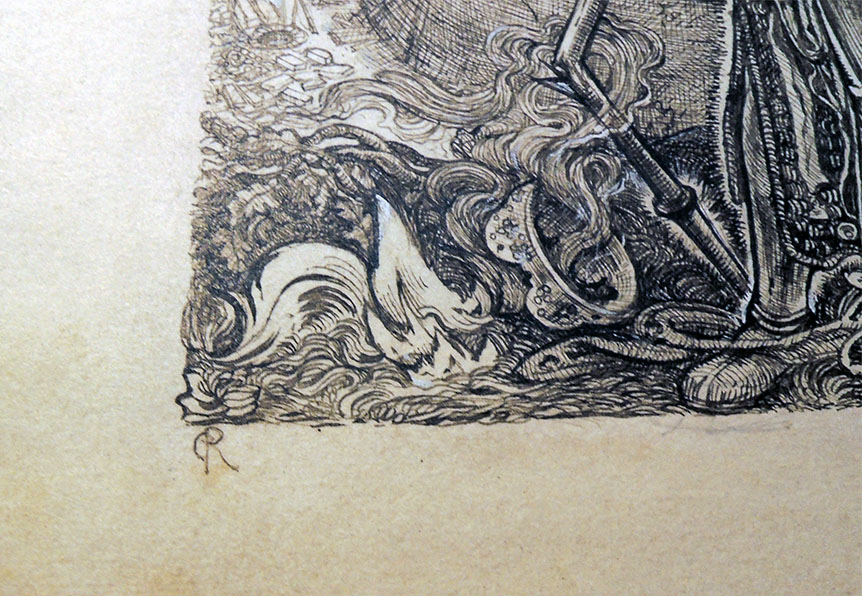

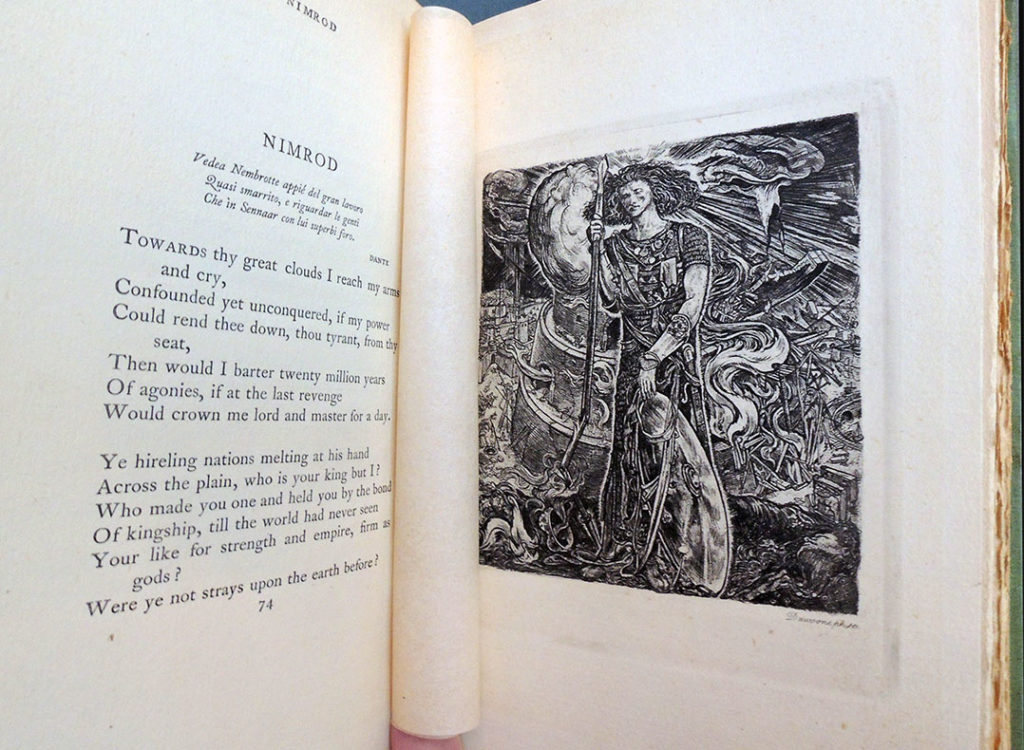

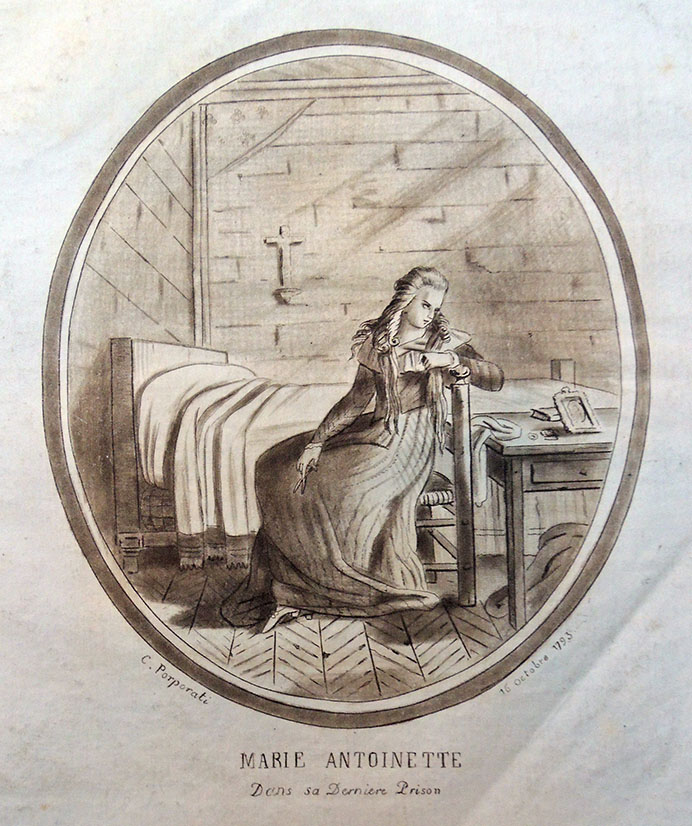

Carlo Antonio Porporati (1741-1816), Marie Antoinette dans sa derniere prison (Marie Antoinette in her prison), October 16, 1793. Etching with roulette. Graphic Arts Collection

Carlo Antonio Porporati (1741-1816), Marie Antoinette dans sa derniere prison (Marie Antoinette in her prison), October 16, 1793. Etching with roulette. Graphic Arts Collection

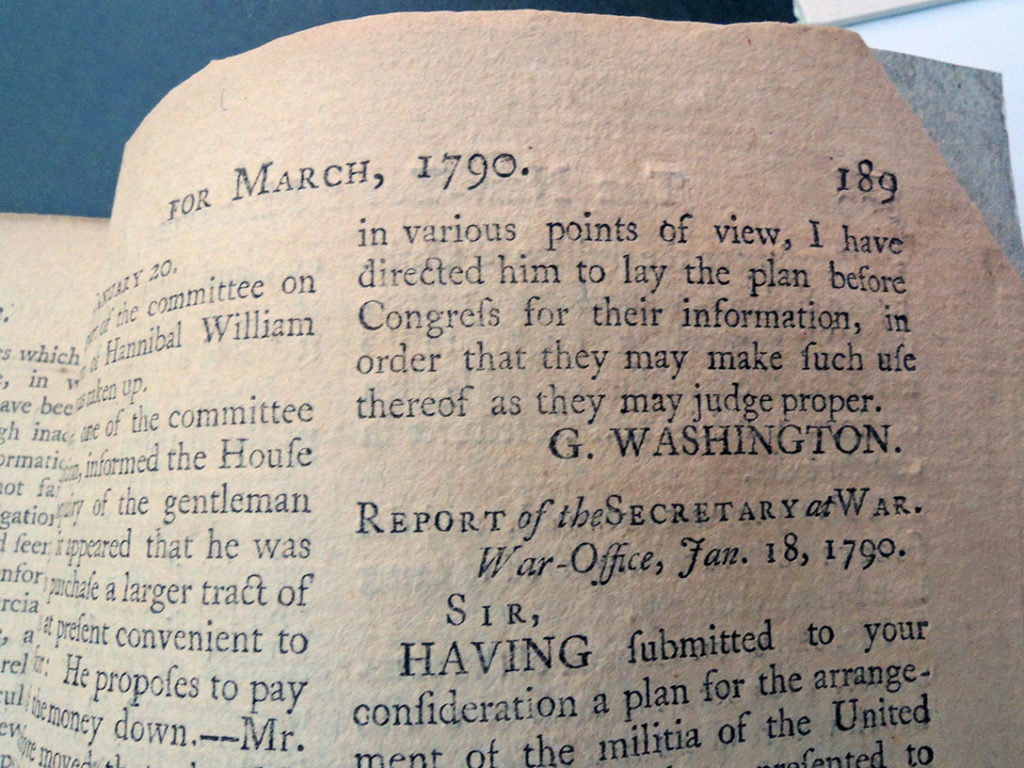

At 11am the next morning, on 16 October 1793, the executioner Sanson appeared. Madame Bault confirmed that he cut the queen’s hair and that the queen, looking back, saw the executioner place the locks of hair in his pocket. “This I saw,” said Madame Bault, “and I wish I had never seen that sight.” At 12.30pm, Marie Antoinette was taken to the guillotine at the Place de la Revolution. After the queen’s head fell it was shown to the crowd, who cried: “Vive la République!”

—https://www.historyextra.com/period/georgian/the-final-days-of-marie-antoinette/

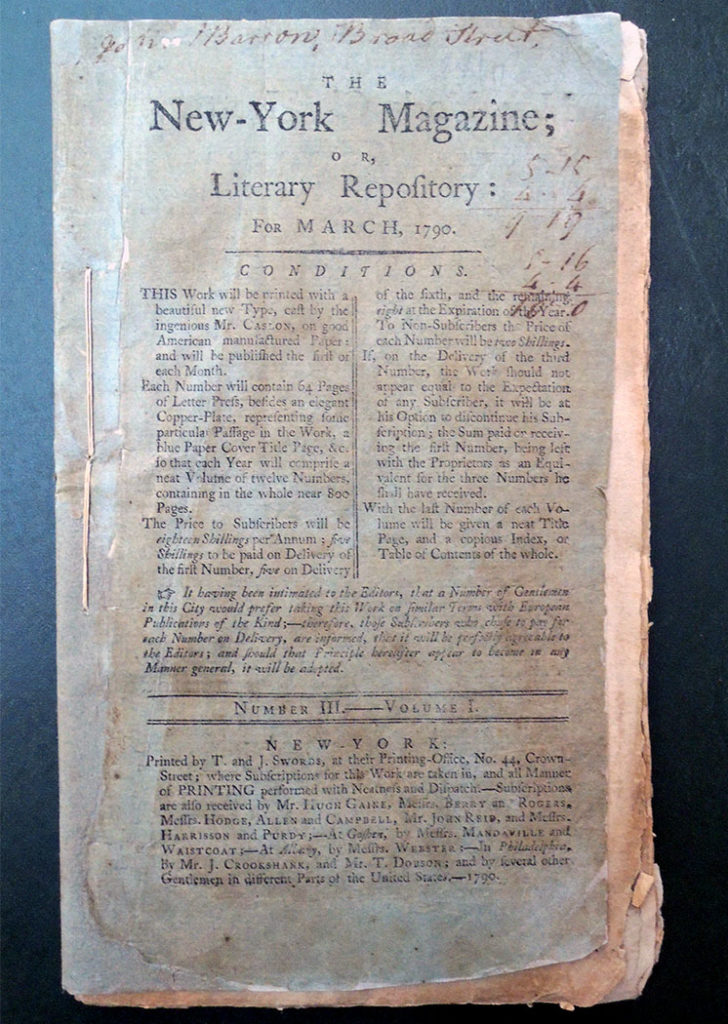

When a recent class asked to see material around Marie Antoinette (1755-1793), this unusual Italian print was pulled. Unusual because the Queen of France is more often depicted in lavish costumes with her hair elaborately styled (see below).

When a recent class asked to see material around Marie Antoinette (1755-1793), this unusual Italian print was pulled. Unusual because the Queen of France is more often depicted in lavish costumes with her hair elaborately styled (see below).

In October 1789, the royal family was placed under house arrest in the Tuileries Palace but it was four years before the Queen’s trial began on October 14, 1793. After only two days, Marie Antoinette was convicted and executed by guillotine on the Place de la Révolution.

The print is the work of the Italian engraver Carlo Antonio Porporati (1741-1816) who spent his early years in Paris and was inducted into the Royal Academy of Artists in 1773. Equally active in French and Italian portraiture, at the time of this print Porporati was living in Naples where he established a school for engravers. —https://doi.org/10.1093/benz/9780199773787.article.B00144687

He dates the print October 16, 1793, the morning of the execution. Like many others, he followed the imprisonment and trial with interest, preparing this image in advance without worrying about the actual likeness.

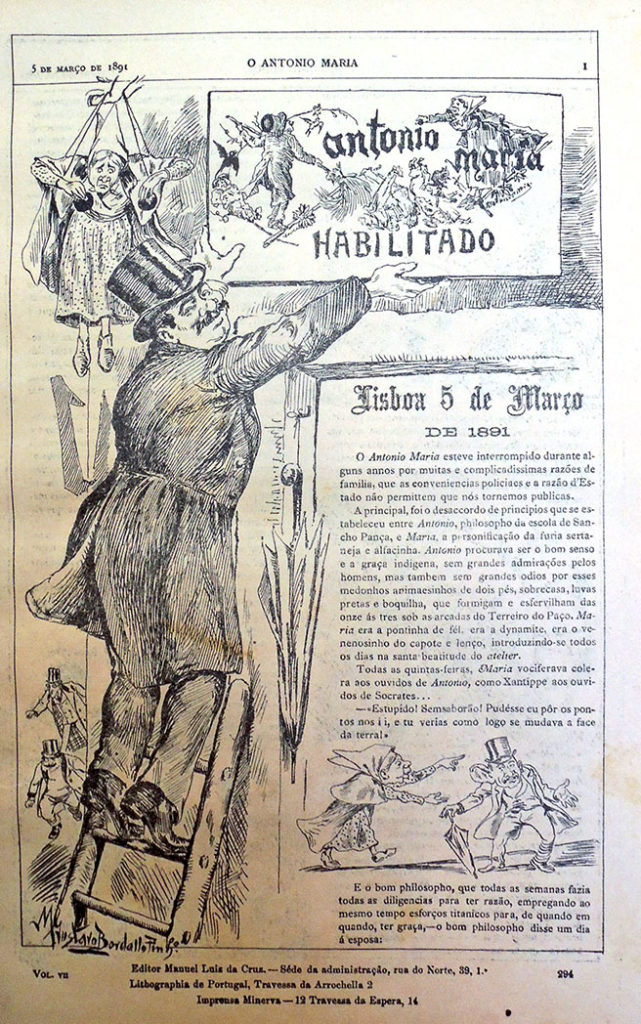

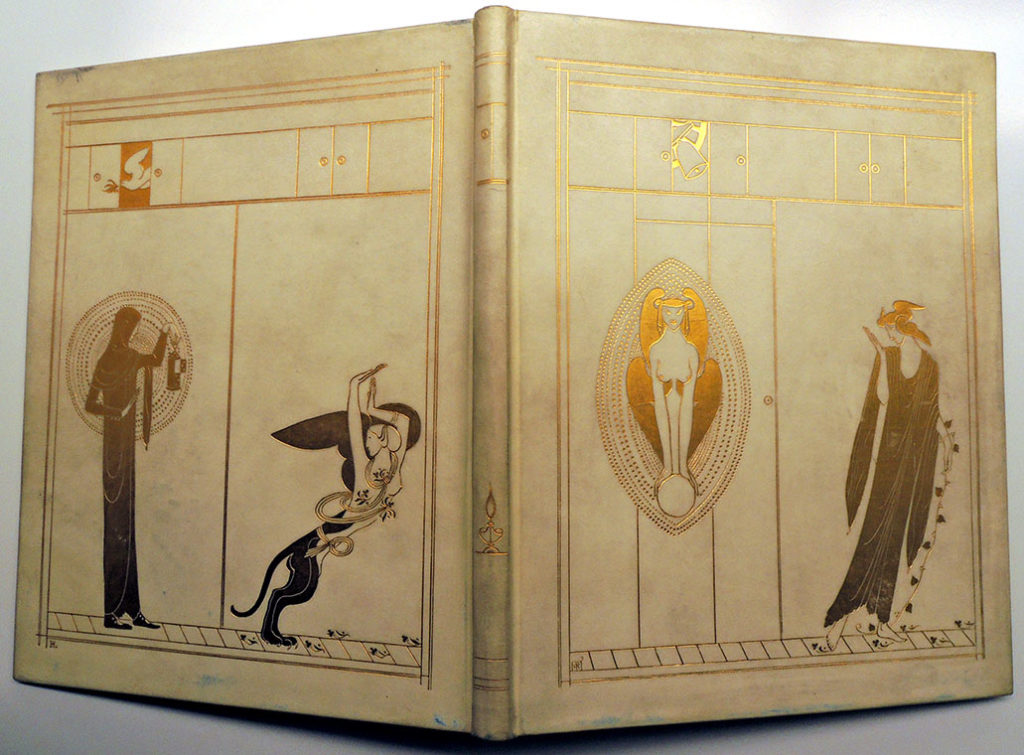

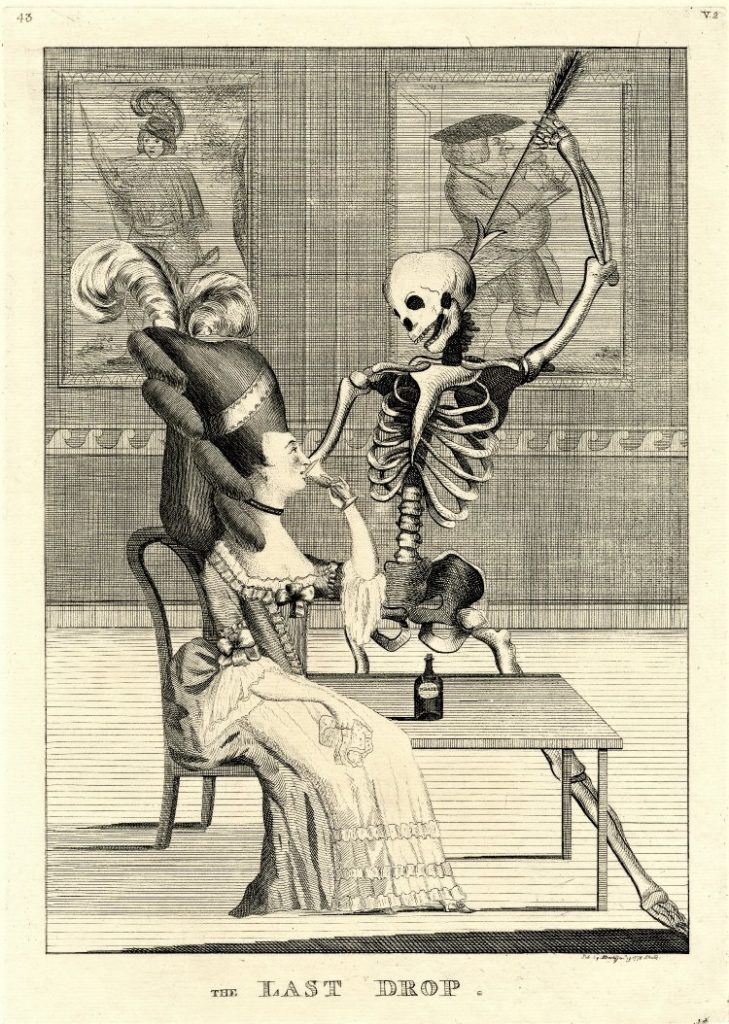

Marie Antoinette Josèphe Jeanne d’Autriche, etched by Pierre Duflos, after Jacques Louis Touzé in Recueil d’estampes représentant les grades, les rangs et les dignités, 1778-1795. (https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b55003867c)

Marie Antoinette Josèphe Jeanne d’Autriche, etched by Pierre Duflos, after Jacques Louis Touzé in Recueil d’estampes représentant les grades, les rangs et les dignités, 1778-1795. (https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b55003867c)