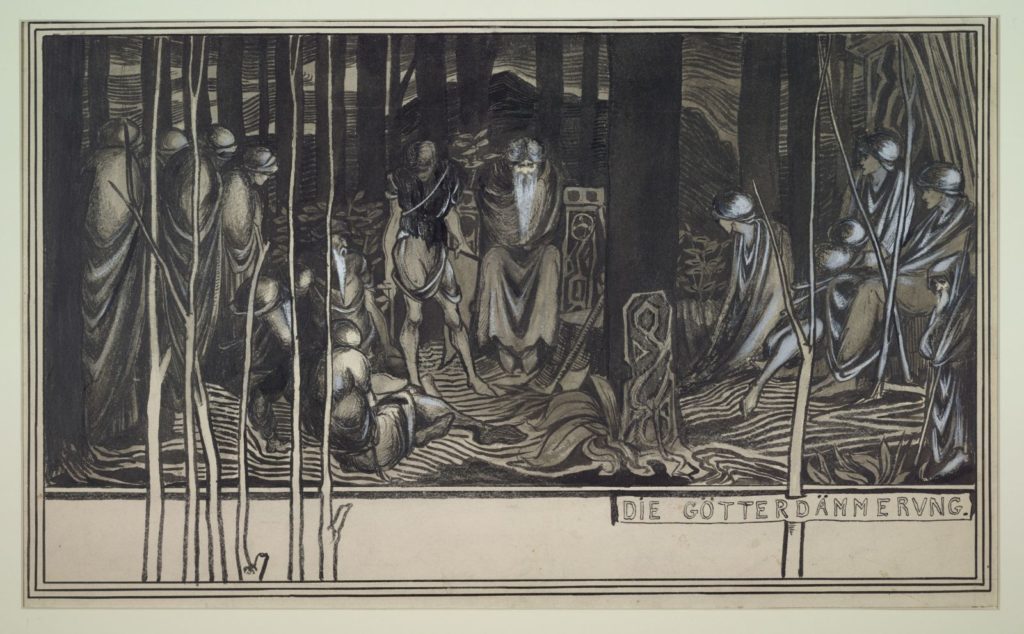

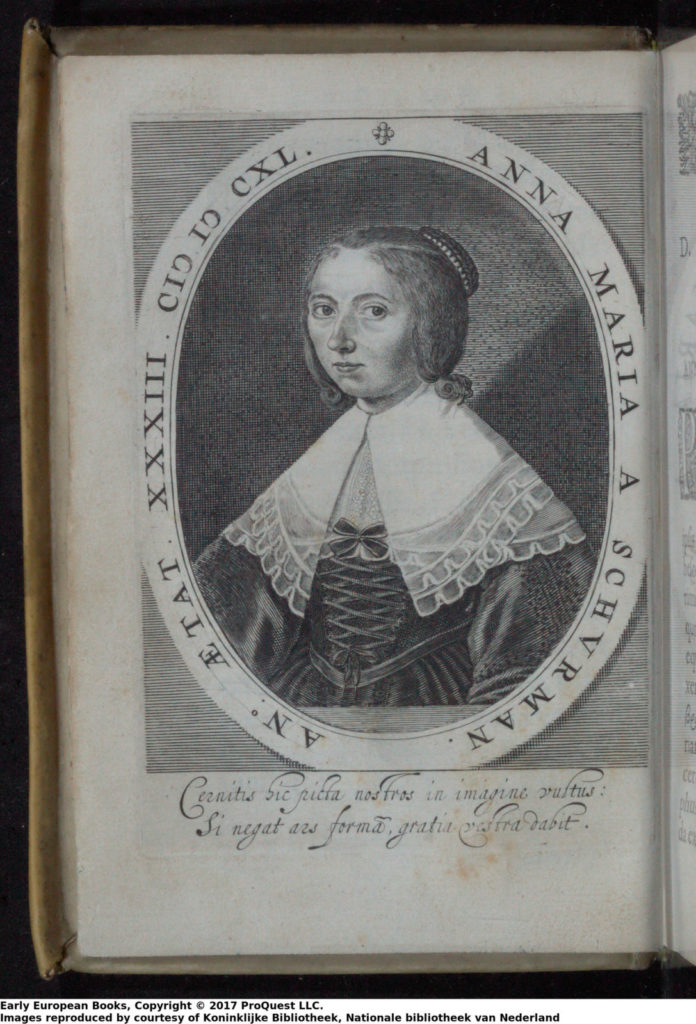

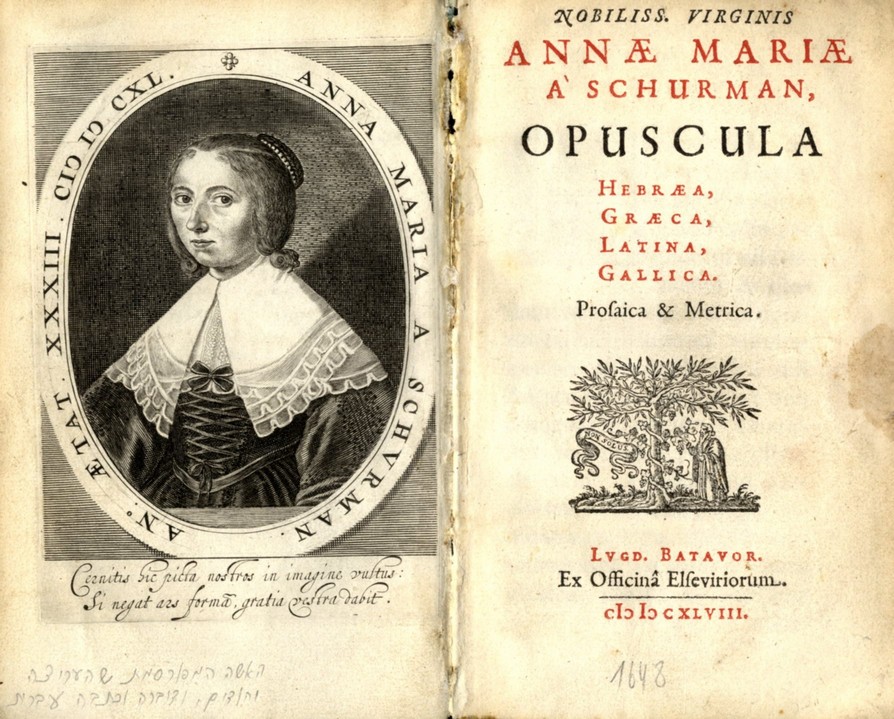

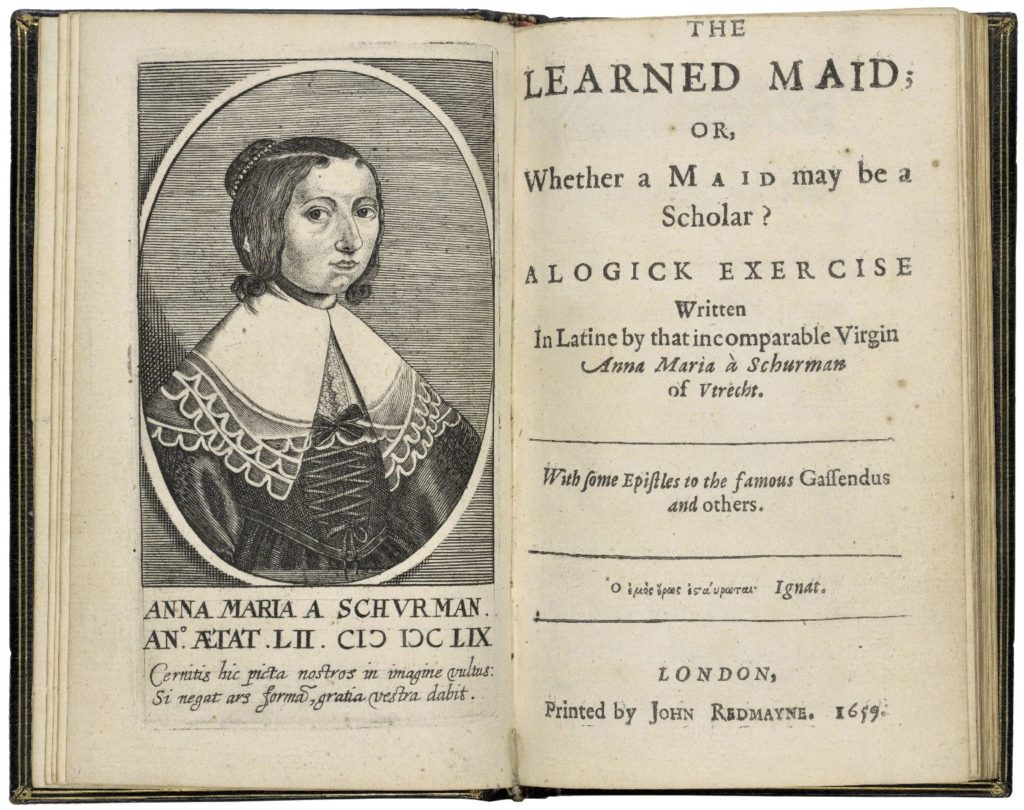

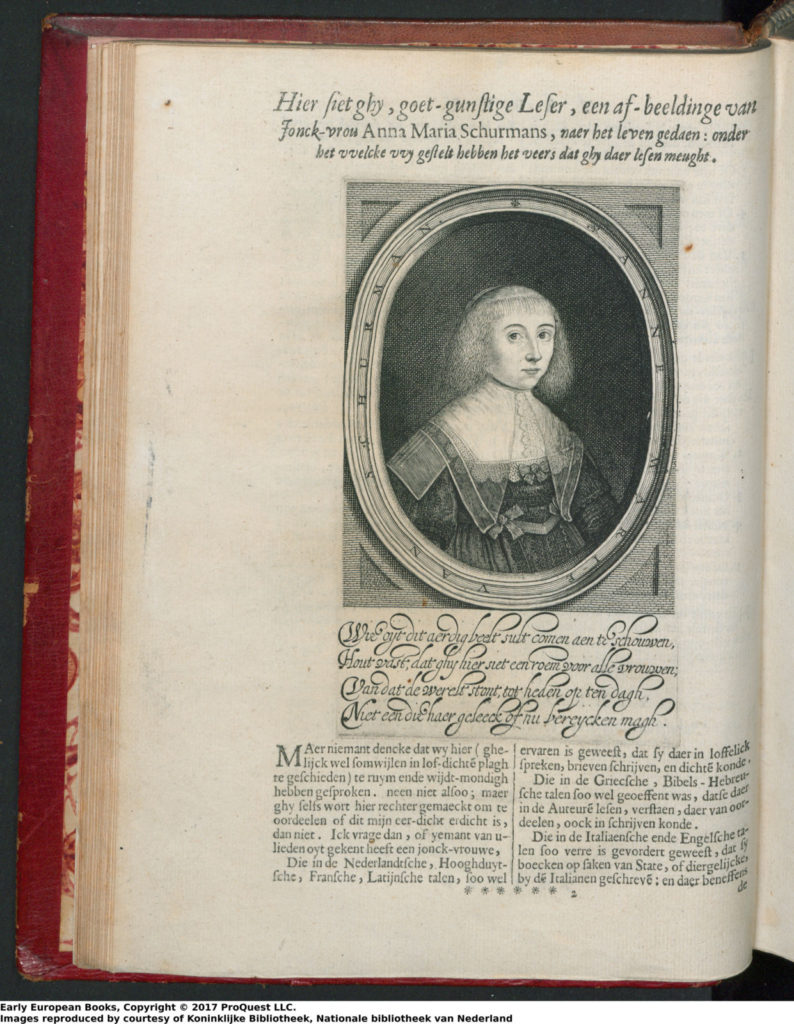

Over the last five weeks of posting projects for those of us at home, by far the most responses have been to a request for women’s history: Who was the first women to graduate from your school, college, or university? What began with the identification of a 1640 (III/IV (Hollstein Dutch and Flemish, v.26, p.113) engraving of the artist and scholar Anna Maria van Schurman (1607-1678), often identified as the first female student at a European university, led to a survey of other notable women who are recorded as being the first to graduate from universities across the United States (and a few outside the US, although that would be a much longer list. See: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Timeline_of_women%27s_education)

https://drive.google.com/a/princeton.edu/file/d/1Gx_g_fKBkQ_Ija-Ps4k_Dza0QPXJEMe2/view?usp=sharing Here is a six-page PDF list of women who were the first graduates from various colleges. The stories are wonderful.

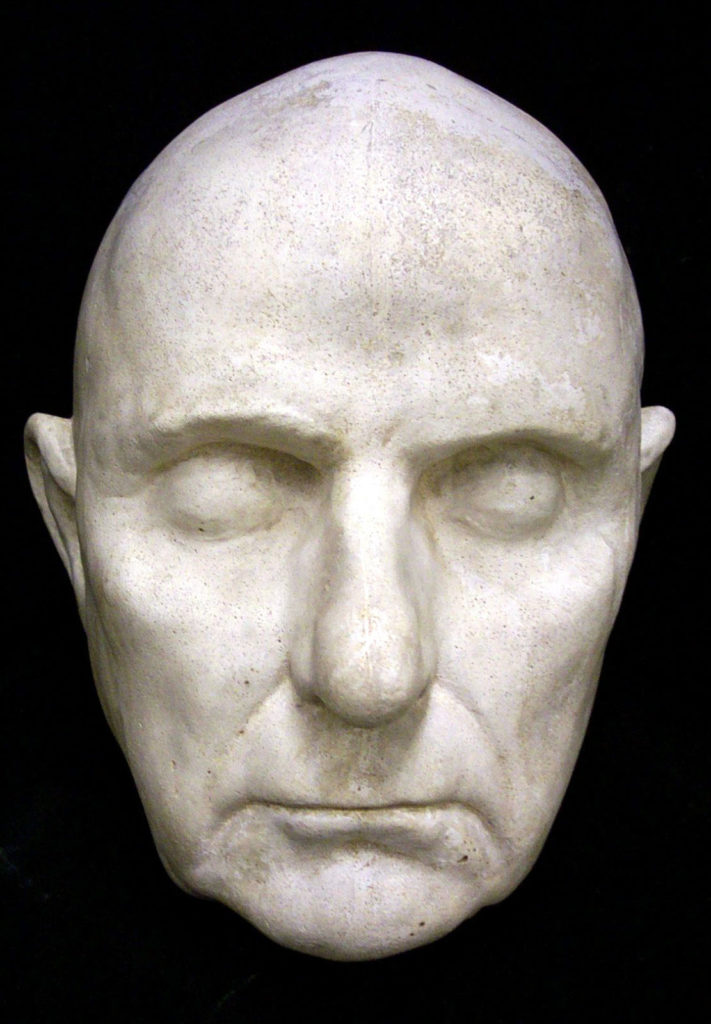

Before Ruth Bader Ginsburg there was Bettisia Gozzadini, who studied law at the Studium of Bologna, dressed as a man, graduating from the university in 1237 and teaching law at her home. There is a bust of Gozzadini at the Museum of the History of Bologna, sculpted by Casa Fibbia sometime between 1680 and 1690. An inscription on its base reads: “Loving daughter, in both rights highly eminent/ Public laws explained and in Bishop’s funeral prayed. Flourished 1242. Died 1261.” Thanks to Janna Brancolini for the image.

From Ohio, there were the “Oberlin Four.” http://www.womenhistoryblog.com notes “Oberlin College was founded in 1833 in Oberlin, Ohio, and became the first college in the United States to admit women as well as men. There were four courses of study: the Female, Teachers, Collegiate and Theological Departments. Women were allowed to study in the Female or Teachers Department. However, in 1837 four women – Mary Kellogg, Mary Caroline Rudd, Mary Hosford and Elizabeth Prall – entered the college degree program, the Collegiate Department. All but Kellogg graduated in 1841 and received the first Bachelor of Arts degrees earned by women in the United States. Kellogg, who had left school for lack of funds, later returned to Oberlin after marrying James Harris Fairchild, a future president of Oberlin College. Mary Caroline Rudd (later Allen) pictured below.

Ellen Swallow Richards (1842-1911) was the first woman admitted to MIT, receiving her S.B. degree in 1873 (the first graduating class of MIT was 1868). The title of her thesis [PDF file] was “Notes on Some Sulpharsenites and Sulphantimonites from Colorado.” In 1875 she appealed to the Women’s Education Association of Boston for help in establishing a laboratory at MIT for the instruction of women in chemistry. The Women’s Laboratory opened in 1876 with Professor John M. Ordway in charge, assisted by Richards. She held the position of instructor in chemistry and mineralogy in the Women’s Laboratory until it closed in 1883. From 1884 to her death in 1911, Richards was instructor in sanitary chemistry at MIT.–https://libraries.mit.edu/mithistory/community/notable-persons/ellen-swallow-richards/

Many schools closely followed the decisions made elsewhere, which influenced their own progress (or lack of). Here is The Harvard Crimson reporting on the decision at Dartmouth College to admit women beginning in the fall of 1972. : https://www.thecrimson.com/article/1971/11/22/dartmouth-to-admit-women-in-fall/

Dartmouth, like Harvard and others, has a complicated history that is not easy to record, given that women were allowed to study at the school long before they were given degrees. The attached PDF is a casual document and if you find mistakes, it can easily be corrected and updated.

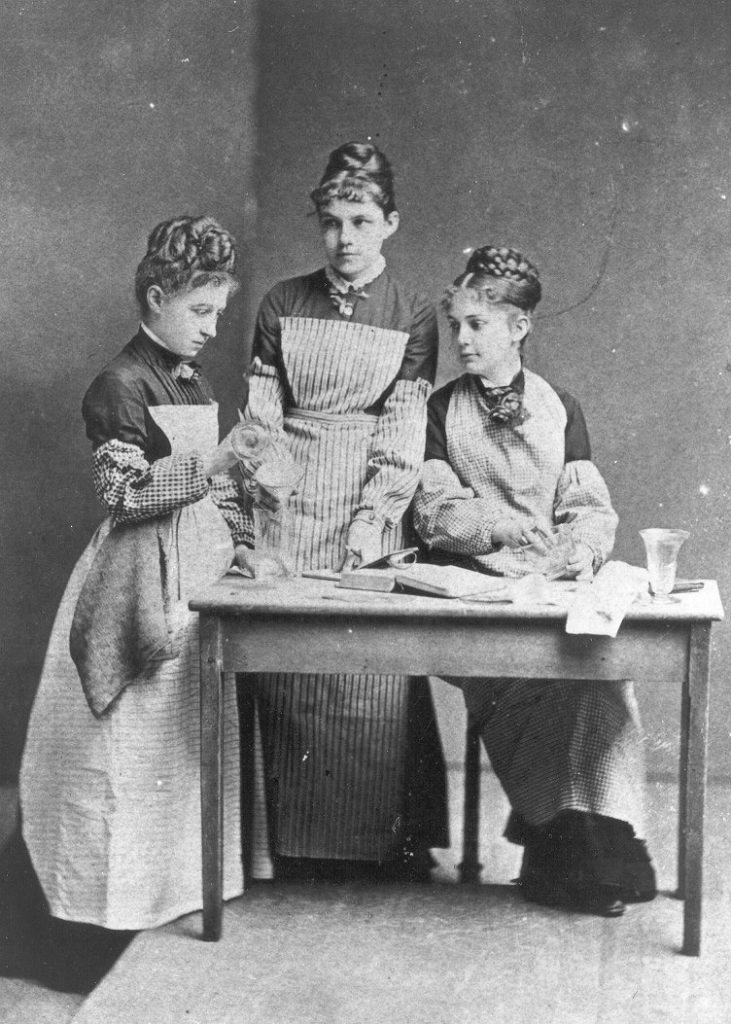

The University of Pennsylvania archives posted this image of the first women to matriculate at UPenn, working in the chemistry laboratory, 1878 (L to R: Gertrude K. Peirce, Anna L. Flanigen, and Mary T. Lewis). “Gertrude Klein Peirce and Anna Lockhart Flanigen met at Women’s Medical College. The two women were the first female students admitted to the University of Pennsylvania. Miss Peirce earned a certificate of proficiency in Chemistry in 1878. She continued her studies in a post-graduate course in 1878 and 1879….”–https://archives.upenn.edu/exhibits/penn-people/notables/women

The University of Pennsylvania archives posted this image of the first women to matriculate at UPenn, working in the chemistry laboratory, 1878 (L to R: Gertrude K. Peirce, Anna L. Flanigen, and Mary T. Lewis). “Gertrude Klein Peirce and Anna Lockhart Flanigen met at Women’s Medical College. The two women were the first female students admitted to the University of Pennsylvania. Miss Peirce earned a certificate of proficiency in Chemistry in 1878. She continued her studies in a post-graduate course in 1878 and 1879….”–https://archives.upenn.edu/exhibits/penn-people/notables/women

Of course, they are not all success stories. On May 21, 1897, men and women, young and old, gathered to protest the admission of women to Cambridge University, as seen in Thomas Stearn’s photograph above. Here’s more: https://graphicarts.princeton.edu/2018/02/22/cambridge-boys-celebrate-when-women-are-refused-degrees/.

Of course, they are not all success stories. On May 21, 1897, men and women, young and old, gathered to protest the admission of women to Cambridge University, as seen in Thomas Stearn’s photograph above. Here’s more: https://graphicarts.princeton.edu/2018/02/22/cambridge-boys-celebrate-when-women-are-refused-degrees/.

If your story is missing, you can still send notes to jmellby@princeton.edu and I will add them. Thank you to everyone who participated.