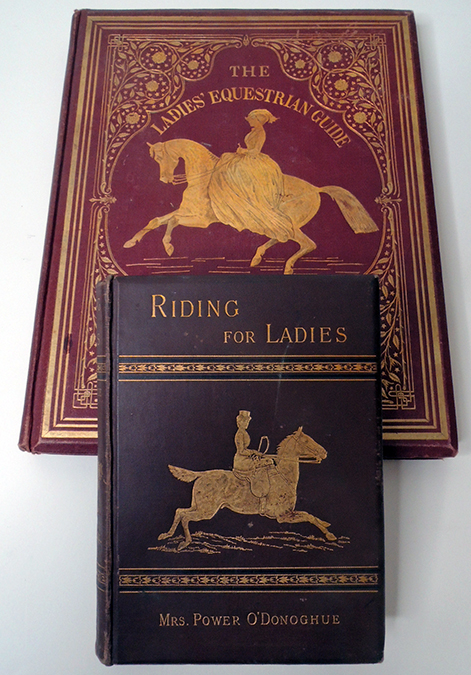

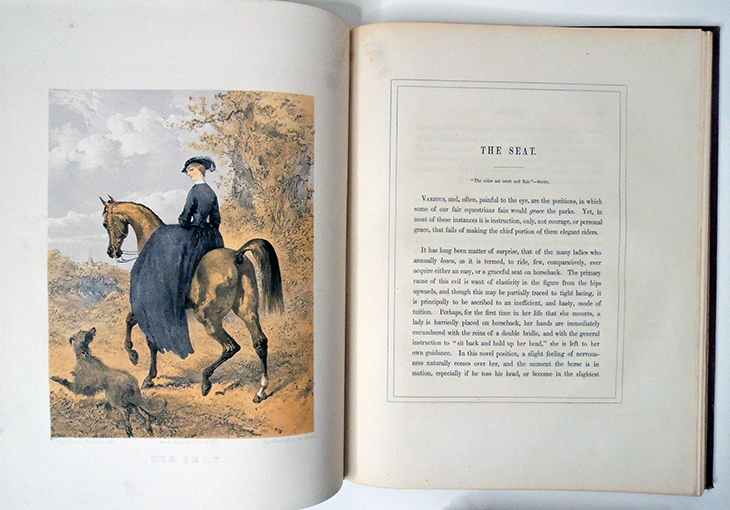

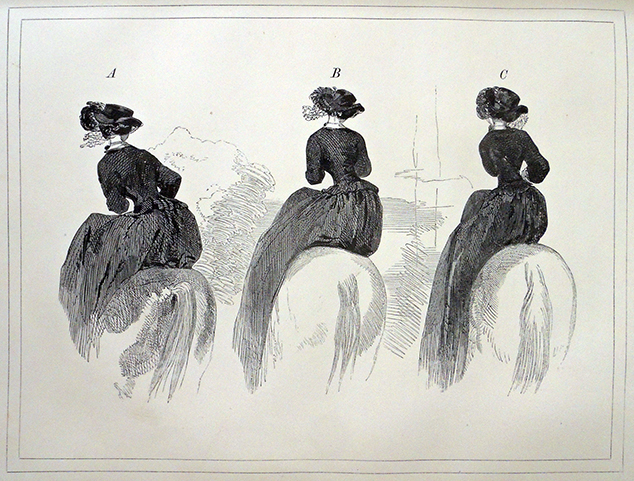

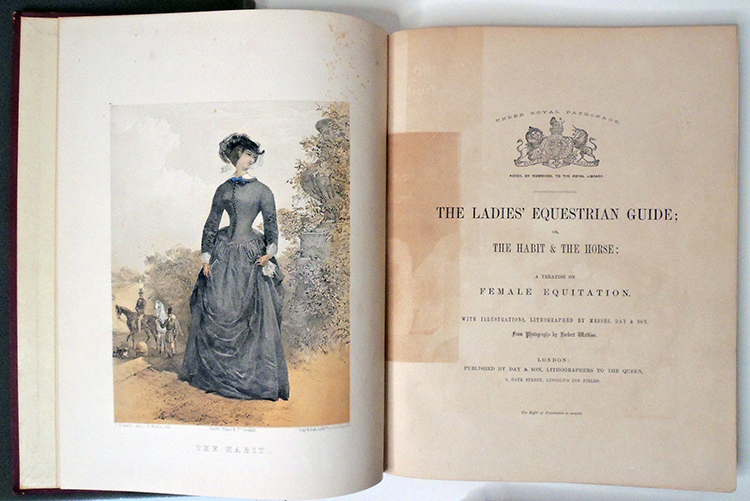

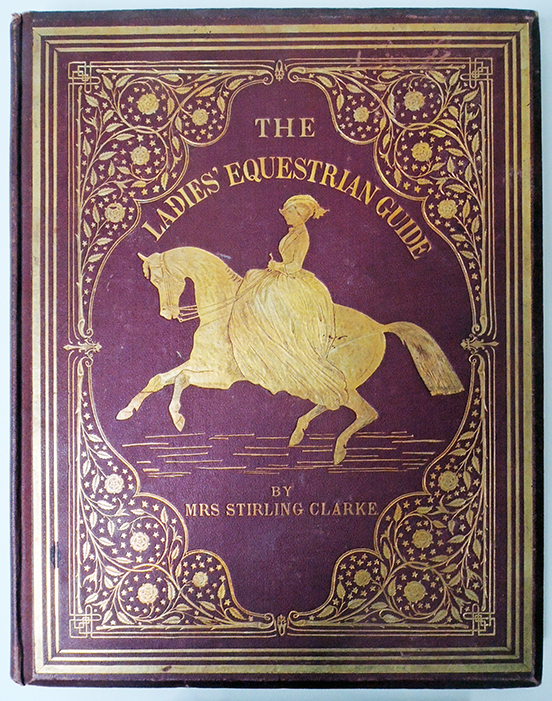

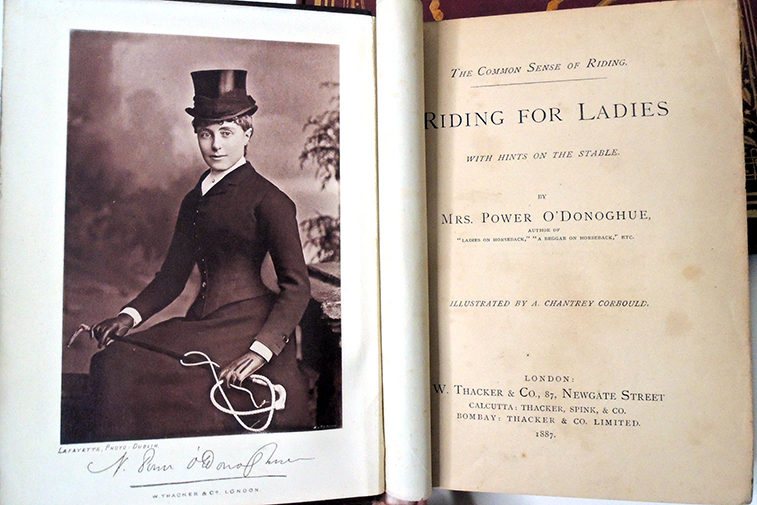

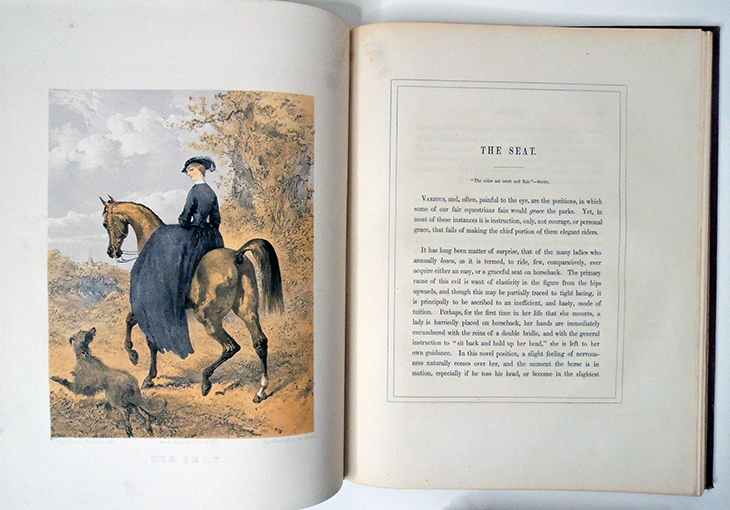

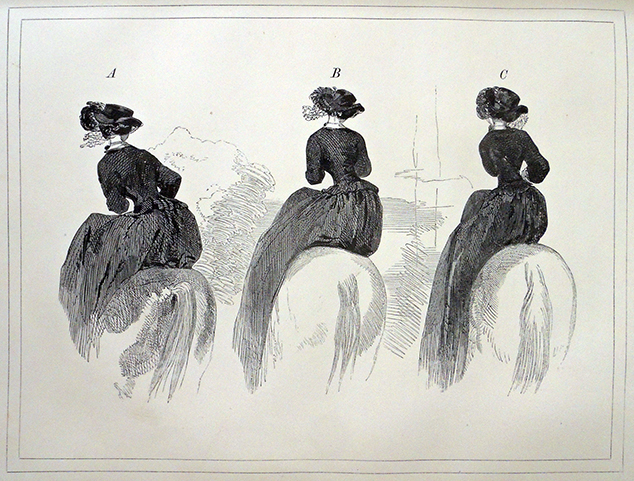

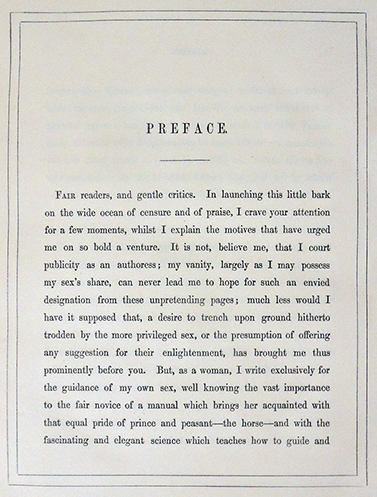

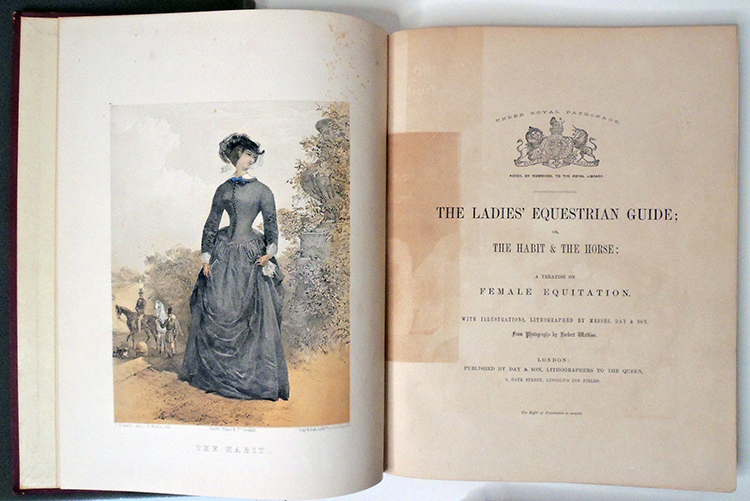

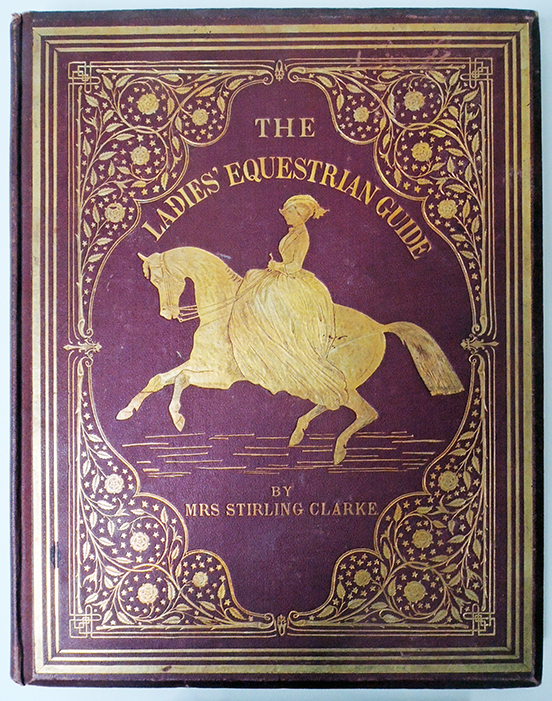

Mrs. Stirling Clarke, The Ladies’ Equestrian Guide, or, The Habit & the Horse: a treatise on female equitation, with illustrations lithographed by Messrs. Day & Son, from photographs by Herbert Watkins (London: Day & Son, [1857]). 9 plates, tinted lithographics by Day & Son after photographs by Herbert Watkins (1828-1916). Graphic Arts Off-Site Storage 2021- in process.

Mrs. Stirling Clarke, The Ladies’ Equestrian Guide, or, The Habit & the Horse: a treatise on female equitation, with illustrations lithographed by Messrs. Day & Son, from photographs by Herbert Watkins (London: Day & Son, [1857]). 9 plates, tinted lithographics by Day & Son after photographs by Herbert Watkins (1828-1916). Graphic Arts Off-Site Storage 2021- in process.

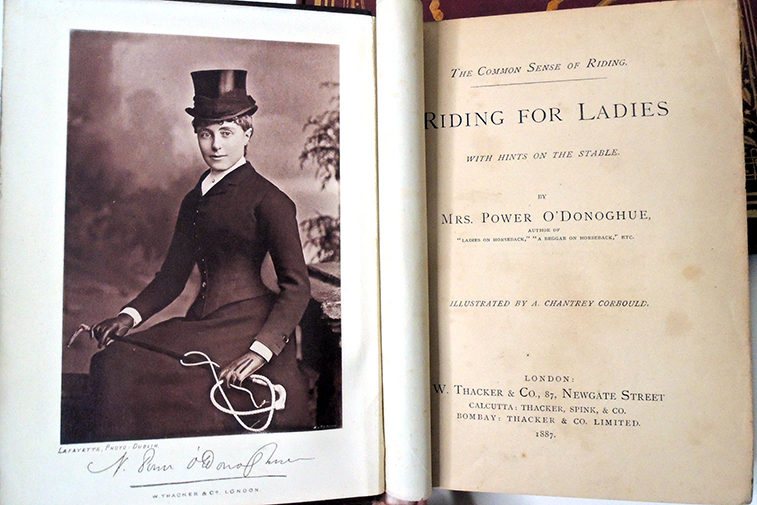

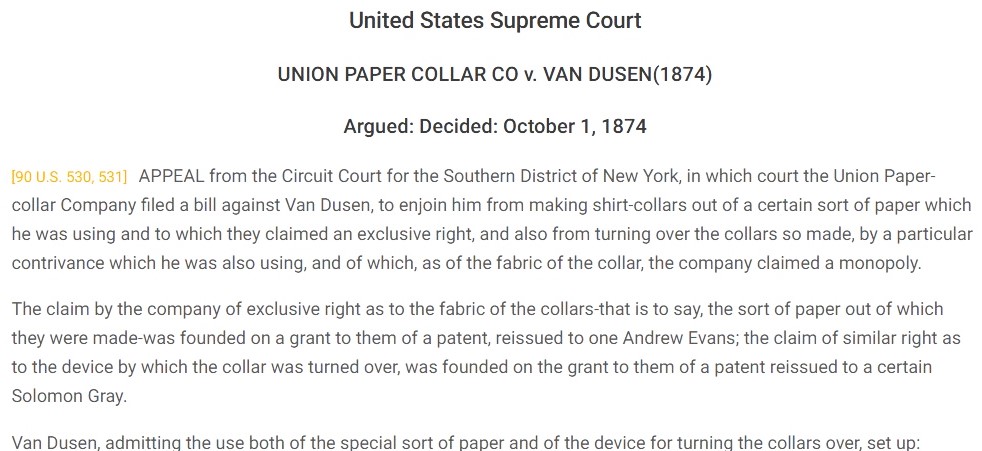

Nannie Lambert Power O’Donoghue (1843-1940) and A. Chantrey Corbould (1852-1920), Riding for Ladies, with Hints on the Stable (London: William Clowes & Sons for W. Thacker & Co., Calcutta, Thacker, Spink, & Co., and Bombay, Thacker & Co., 1887). Woodburytype frontispiece. Graphic Arts Off-Site Storage 2021- in process

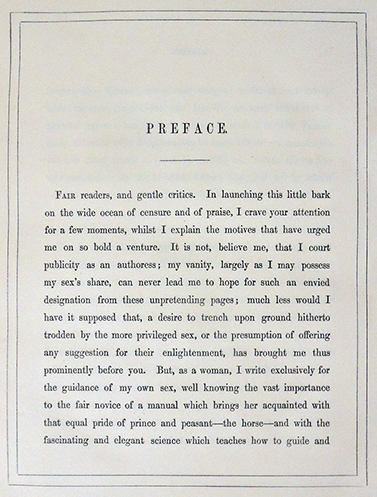

The Graphic Arts Collection is fortunate to have acquired two works by female authors concerning horsemanship for upper class women in the 19th century. It is unfortunate that the earliest by a Mrs. Clarke cannot be identified with her own name but only by her husband’s. Written in 1857, Clarke’s book comes a full twenty year before that of Nannie Power O’Donoghue’s work. It is a thorough discussion of horsemanship including notes on stabling, training, shoeing, and doctoring, by and for women.

Mrs. Stirling is a mystery beyond her marriage, she even leaves her name off the title page, preface, or introduction. Her preface begins by assuring any man reading the book that he need not worry. She has no desire to “trench upon ground hitherto trodden by the more privileged sex” nor does she offer “any suggestion for their enlightenment.” So, if you are of the male sex, shut your computer and stop reading.

Stirling continues, “I write exclusively for the guidance of my own sex, well knowing the vast importance to the fair novice of a manual which brings her acquainted with that equal pride of prince and peasant—the horse—and with the fascinating and elegant science which teaches how to guide and govern him, and how to guide and govern herself with respect to this noble creature.” Riding well needs training, as Stirling quotes, “True knowledge comes from study, not by chance, As those move easiest who have learned to dance.”

Riding was in the mid-nineteenth century a regular activity among women, as she comments: “Some years ago, riding was by no means general amongst the fair sex; then ladies on horseback were the exception and not, as now, the rule, but “grace à notre charmante Reine,”

“Whose high zeal for healthy duties

Set on horseback half our beauties,”

there is now scarcely a young lady of rank, fashion, or respectability, but includes riding in the list of her accomplishments; and who, whether attaining her end or not, is not ambitious of being considered by her friends and relatives, “a splendid horsewoman.’ Yet how few can really claim this envied appellation! Habit may do much, and, coupled with science, a great deal more; but good riding, with very few exceptions, is neither a habit nor an instinct. Dancing we all know to be an instinctive motion, a natural expression of joy ; but mark the dancing of the rustic milkmaid, and that of the educated and accomplished lady; the one is an untutored, clumsy bound, the other the very poetry of motion ; and the latter should riding be.”

The second acquisition by a woman for women is Nannie Lambert Power O’Donoghue‘s Riding for Ladies [top] with illustrations by A. Chantrey Corbould (1852-1920). Perhaps it was her athleticism that allowed Power O’Donoghue, also known as Ann Stewart Lyster Lambert, to live to be 97 years old. While she wrote many books, she was best known for Ladies on Horseback, followed a few years later by Riding for Ladies (1887).

Originally published in a series of articles in the Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News and Lady’s Pictorial, Riding for Ladies brought her writing together in a book so popular it is recorded as selling “more than 94,000 copies.” Unlike Stirling, her name is proudly announced on the title page and the book is filled with her many achievements and personal stories.

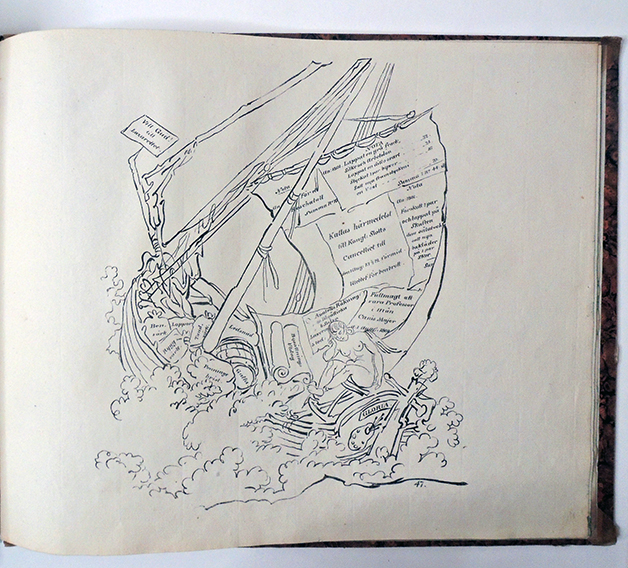

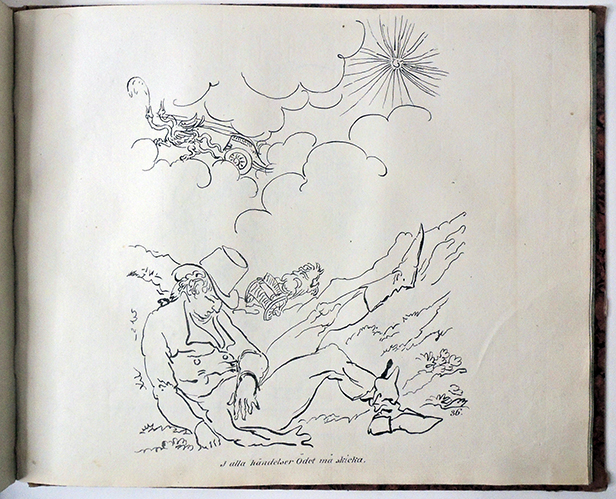

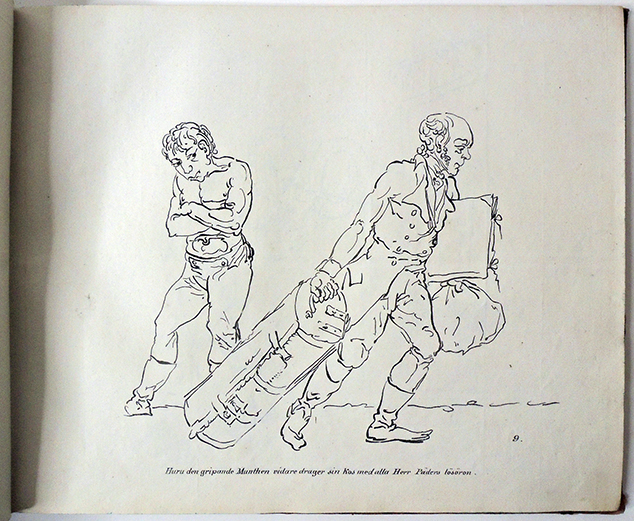

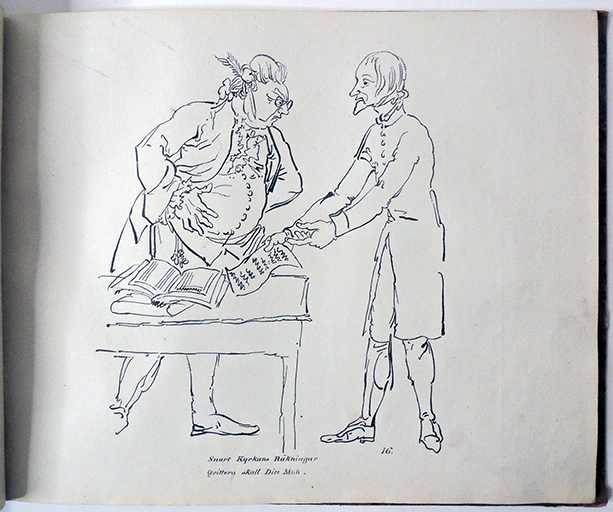

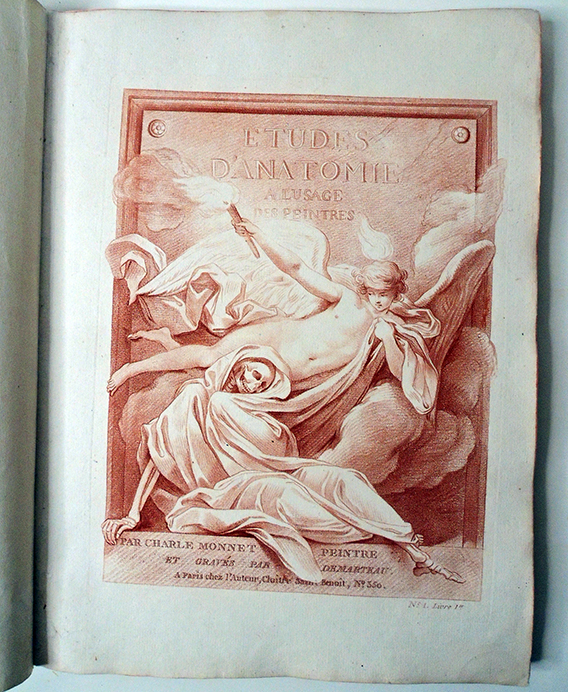

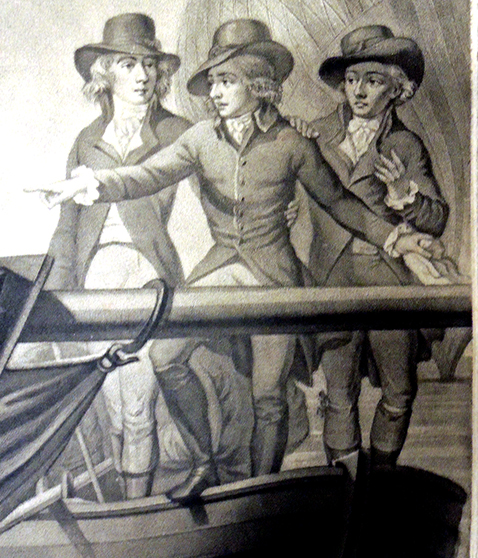

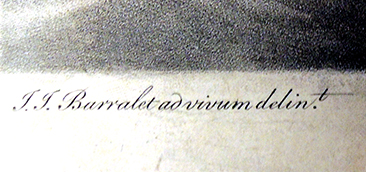

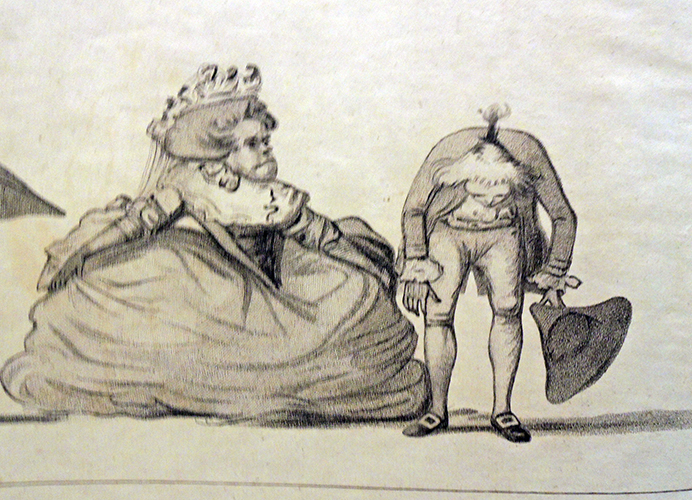

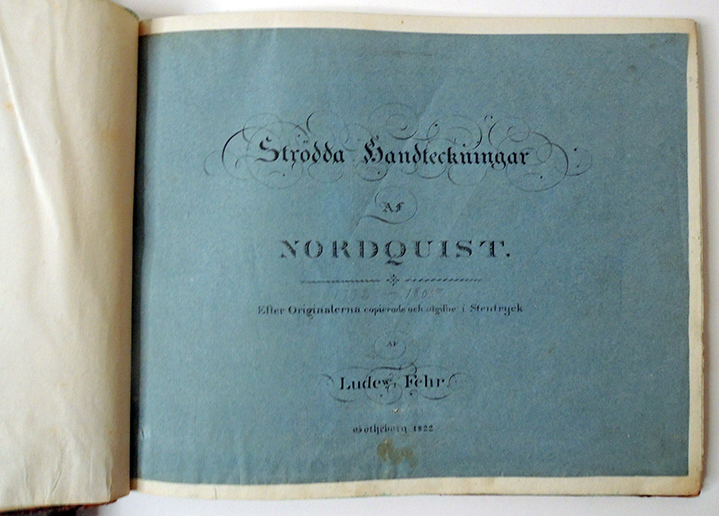

Ludwig Fehr after drawings by Pehr Nordqvist (1771–1805), Strödda handteckningar … Efter originalernacopierade och utgifne i stentryck … [Scattered drawings…after the originals, copied and published in lithography] (Gothenburg: Ludwig Fehr, 1822). 48 lithographs. Graphic Arts Collection GA2021- in process

Ludwig Fehr after drawings by Pehr Nordqvist (1771–1805), Strödda handteckningar … Efter originalernacopierade och utgifne i stentryck … [Scattered drawings…after the originals, copied and published in lithography] (Gothenburg: Ludwig Fehr, 1822). 48 lithographs. Graphic Arts Collection GA2021- in process