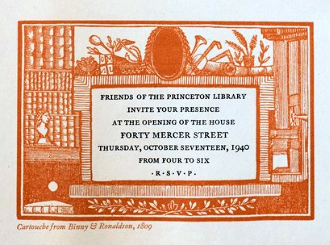

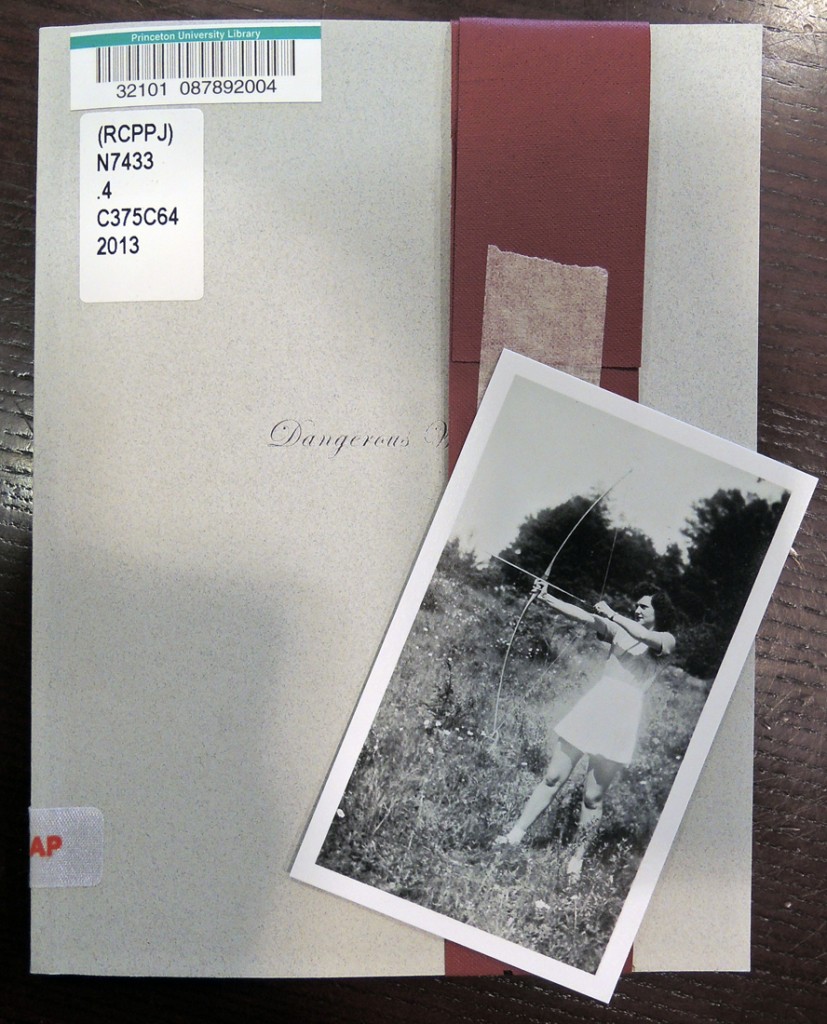

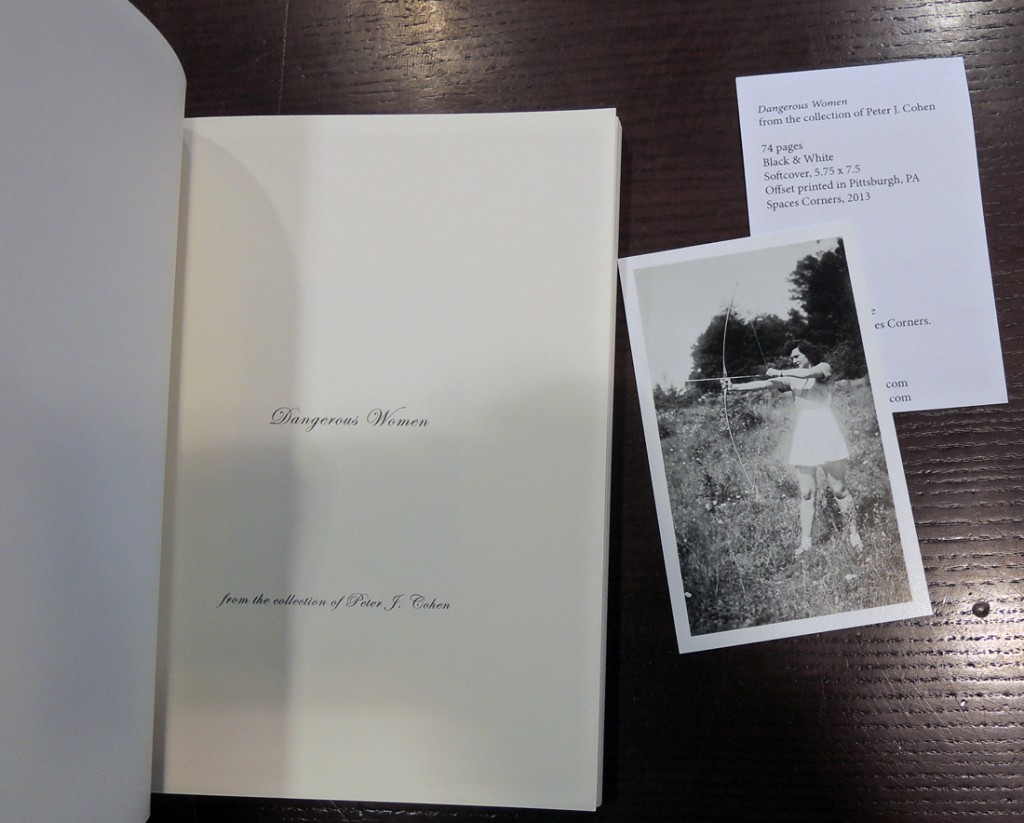

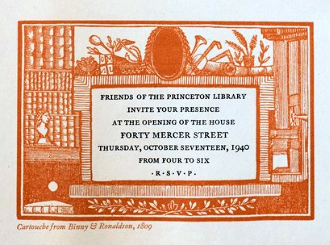

The first page of the Princeton Print Club scrapbook, now available online at http://arks.princeton.edu/ark:/88435/td96k526s, holds a small card that reads “Friends of the Princeton Library invite your presence at the opening of the house Forty Mercer Street Thursday, October seventeen, 1940 from four to six, R.S.V.P.”

The letterpress text is neatly set inside a decorative cartouche copied from a type specimen catalogue of Binny and Ronaldson owned by Elmer Adler (1884-1962). Around it on the page are placed no less than six articles announcing the opening of Alder’s printing library at Princeton along with a program of instruction in the graphic arts.

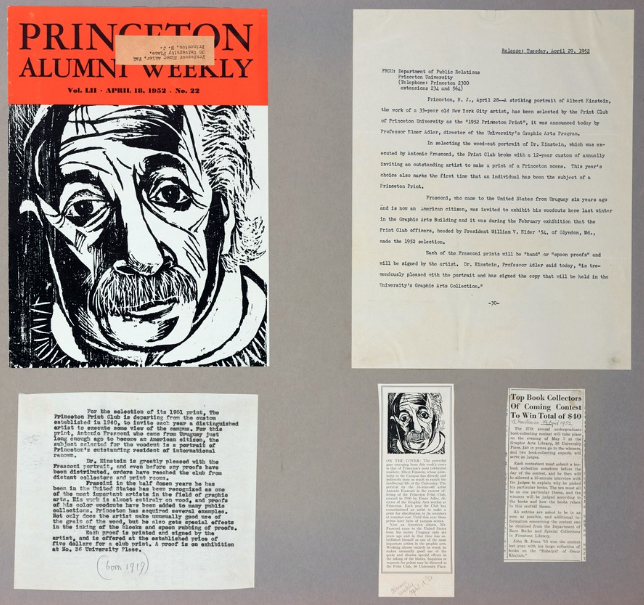

Writing in the Princeton Alumni Weekly, John F. Peckham, Class of 1940, noted that Princeton was not alone in recognizing a need for such a program. In 1938, the newly appointed librarian of Harvard University’s library, William Jackson (1905-1964), asked Philip Hofer (1998-1984) to head the Department of Printing and Graphic Arts, the first such department in the country. That same year, Massachusetts Institute of Technology established the Dard Hunter Paper Museum and hired Hunter (1883-1966) as its curator.

Adler’s earliest Princeton supporters and collaborators in this venture were Lawrance Thompson (1906-1973), professor of English and American Literature, and curator of the Library’s Treasure Room, along with Francis Adams Comstock, Class of 1919 (1897-1981) professor of architecture and a talented visual artist. Thompson introduced Adler to the other Friends of the Princeton University Library (FPUL) in a long piece for the Princeton University Library Chronicle, published in November 1940. “Those of us who have admired the adventurous spirit with which Mr. Adler has embarked on a variety of uncharted seas, in the past, feel confident that his voyage to Princeton is the beginning of another equally successful saga.”

Thanks to Robert Cresswell, Class of 1919, chairman of the FPUL, and a grant from the Carnegie Foundation, Adler was invited to Princeton for a period of three years with the understanding that the total cost of the program, budgeted at $18,000, would be covered by the FPUL, while the “University would not bear any of the responsibility for financing or continuance of the program; and while Mr. Adler would be attached to the staff of the library as research associate in the graphic arts, he would not be given faculty rank and students taking his courses would not be given curriculum credit.”

Once the contract was signed, an early suggestion was to locate Adler in one of the eating clubs along Prospect Avenue. Lawrence approached the Cottage Club in 1939 but wrote Adler of his disappointment when, “They voted against the housing of the collection in the library . . . [since] the library room and particularly the room beyond was needed for football weekends when the house overflows with luncheon and cocktail guests.”

Another plot would have placed the collection in the damp basement of 20 Nassau Street, with Adler residing at the Nassau Club. It was only after Adler had “worn to a frazzle several real-estate agents, who showed him practically every available house to rent in Princeton, did he settle on the dignified, hundred year old and vacant Miller house at Forty Mercer Street.”

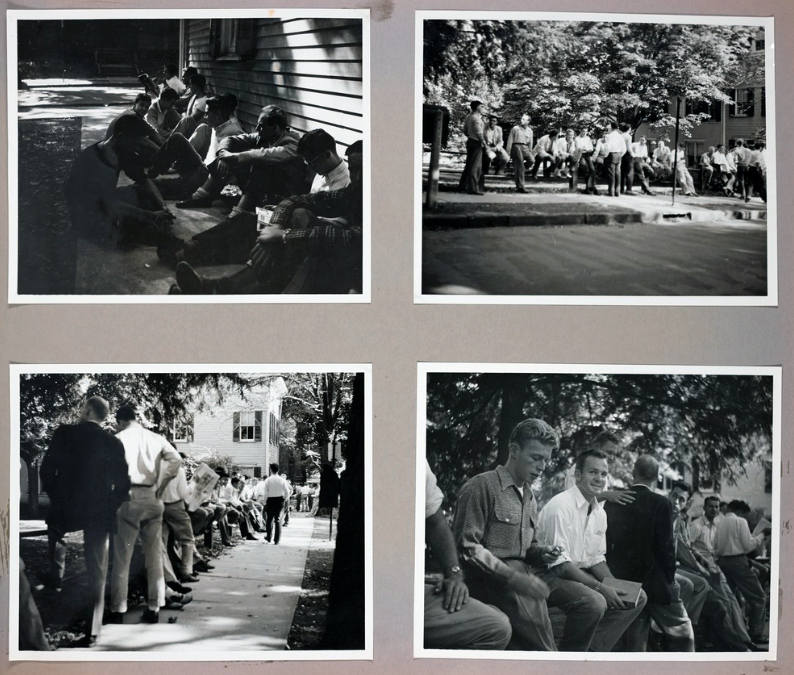

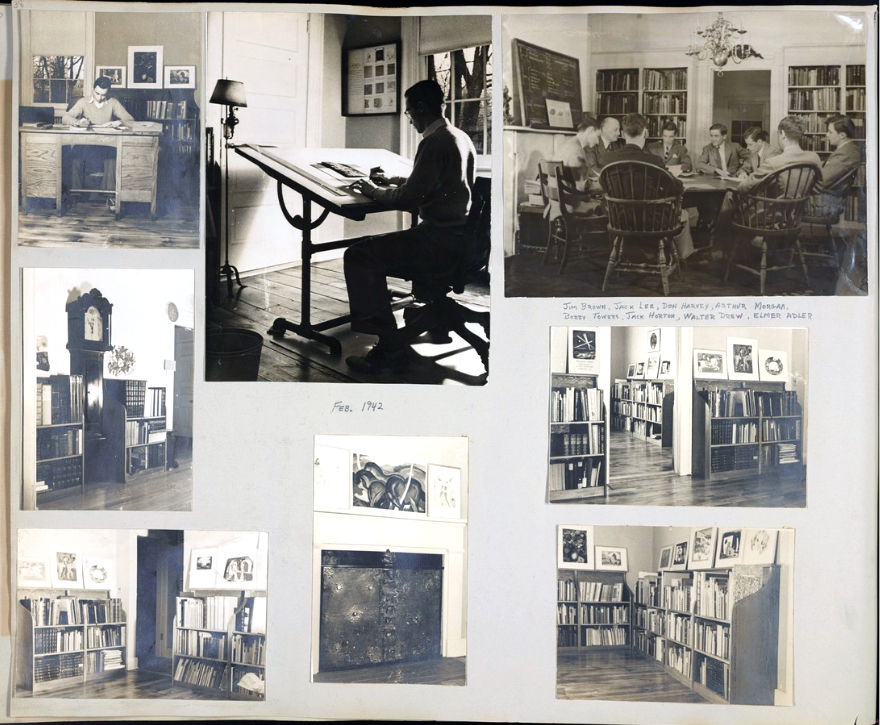

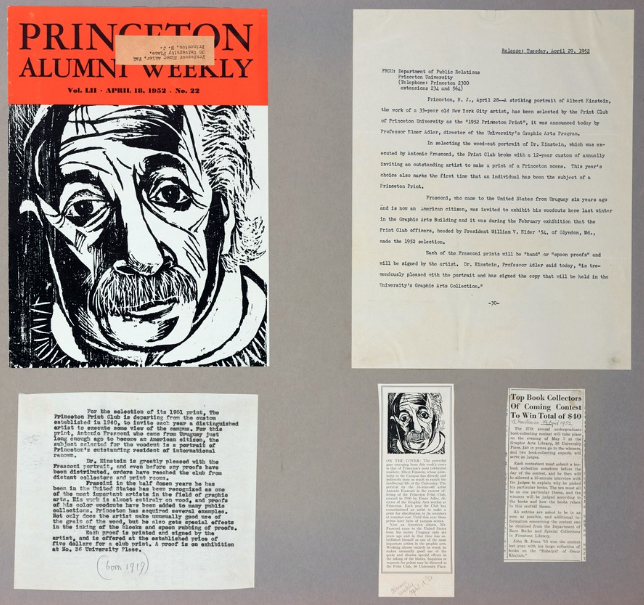

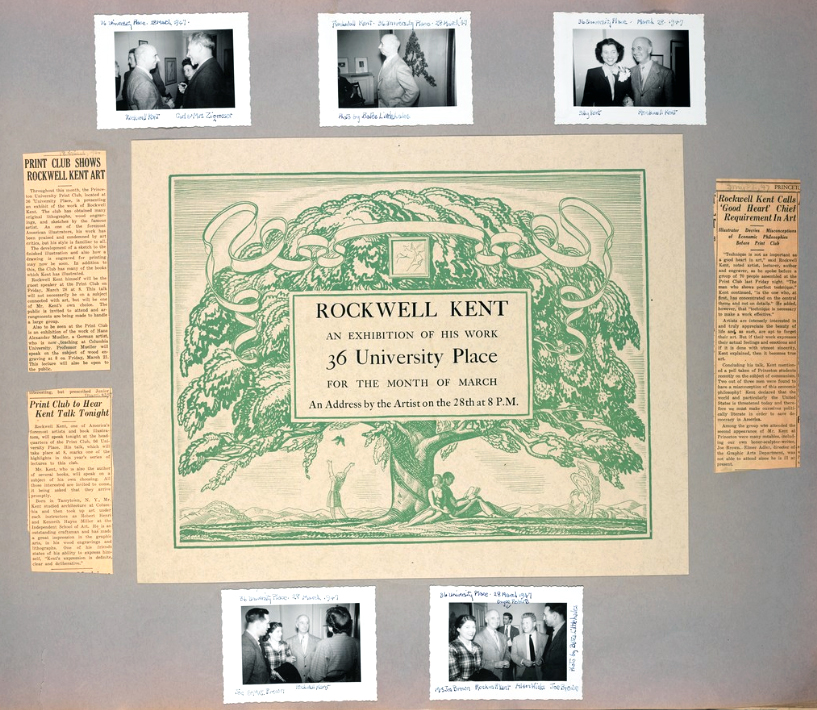

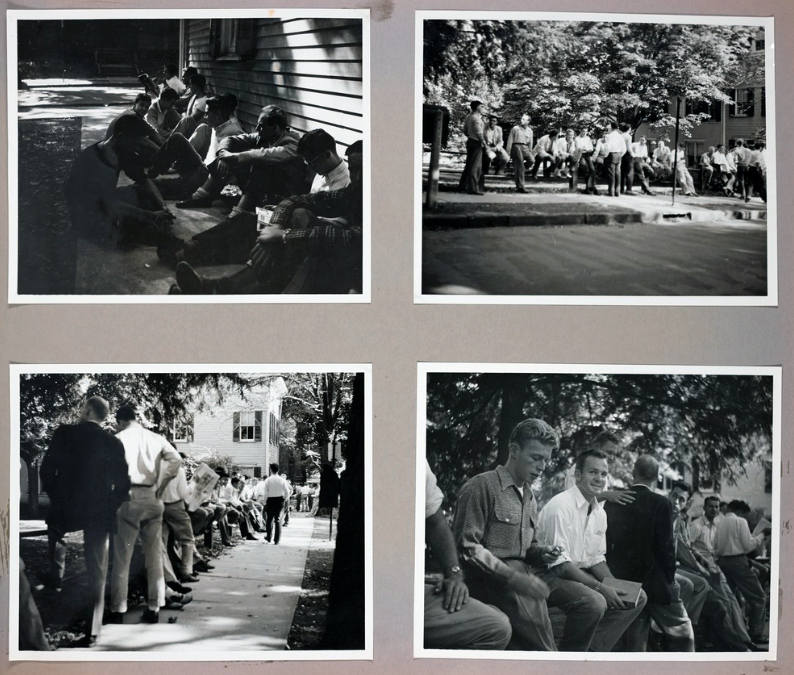

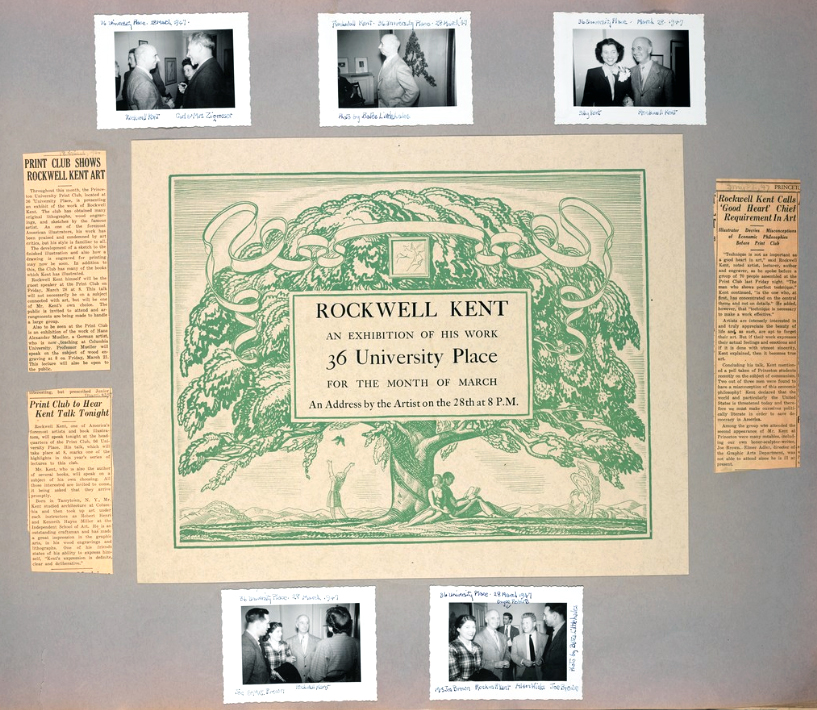

Within the first year of his tenure, Adler transformed the modest frame building on Mercer Street into a vibrant nucleus teeming with activities, displays, celebrated guests, and giveaways. Its most consuming project was The Princeton Print Club and 40 Mercer became known as its clubhouse. By the end of the 1940-1941 school year, the student’s monthly The Nassau Sovereign proclaimed Elmer Adler “an amazing man and his brilliant house—each a new nerve center of campus activity.”

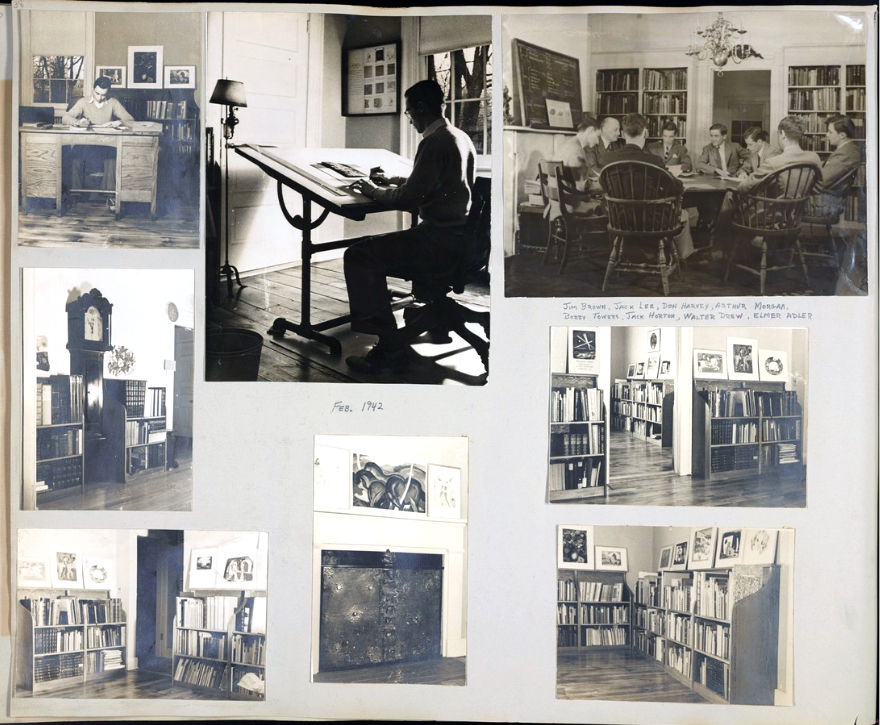

With the fall semester quickly approaching, Adler swung into action and had University carpenters, painters, electricians, plumbers, and others renovate the building into a series of small meeting rooms and galleries, along with an apartment where he would live during the week. The three floors included a working print shop, a library, an exhibition gallery, print room, and in the basement, a smoking room where the anti-smoking, anti-drinking Adler rarely appeared.

By October, the doors on Mercer Street opened with a selection of Adler’s personal collection of prints and printed books on view. “Faculty members, students, and Princeton residents yesterday turned out for the first formal showing of a collection of over 8,000 books and 4,000 prints belonging to Elmer Adler, a research associate on the staff of the University Library,” announced the Daily Princetonian.

“The collection which will provide the basis for informal courses on various aspects of the graphic arts is located at 40 Mercer St. and is open to the public. . . Individuals wishing to use the collection for study and research should obtain admission cards from Lawrance Thompson in the University Library Treasure Room. However, those interested in the collection as an exhibit may take advantage of the open invitations, which will be arranged serially by the Friends of the Princeton Library.”

To learn more about the Princeton Print Club, visit the digital scrapbook at: http://arks.princeton.edu/ark:/88435/td96k526s.

Although the book is inscribed: “Delivered August 14, 1947. Pasting through September 14, 1947 by Wm. G. McLaughlin Jr [Club President],” someone has added several more pages, including information on the new graphic arts curator Gillett Griffin in 1953.

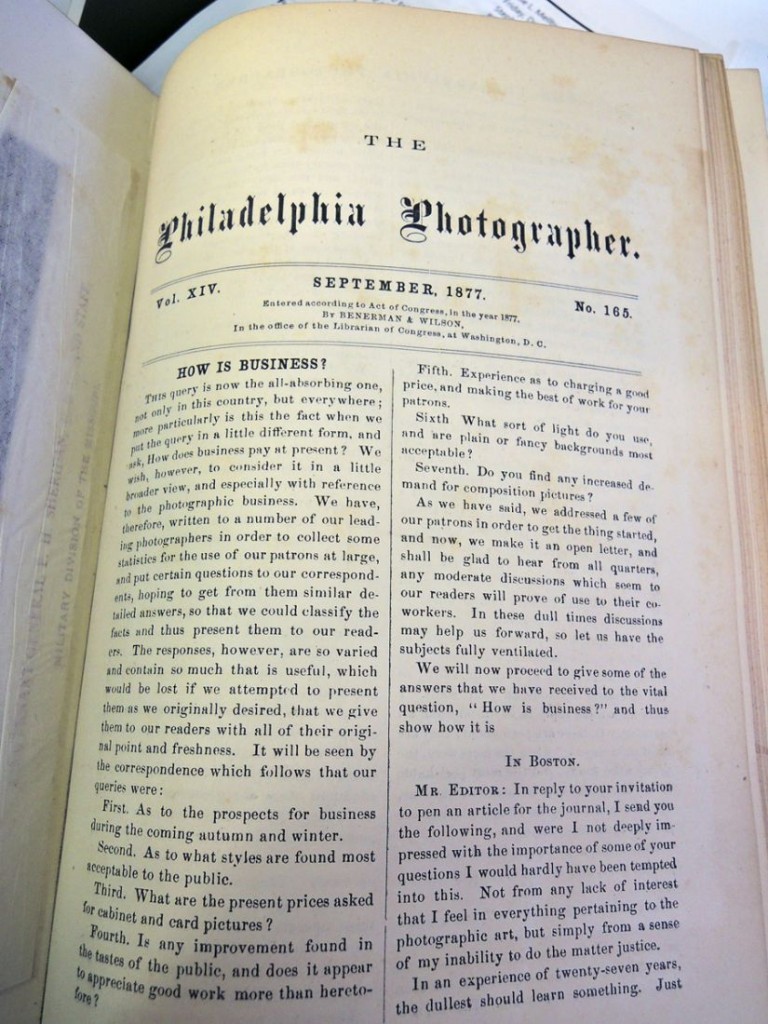

See also: https://graphicarts.princeton.edu/2014/05/27/photography-and-the-princeton-print-club/

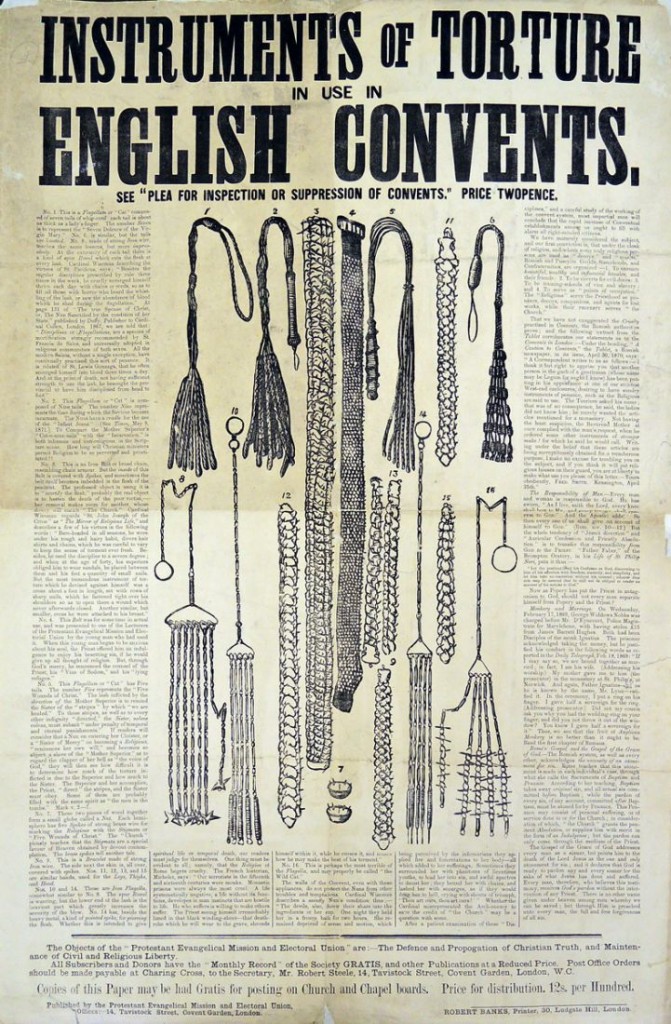

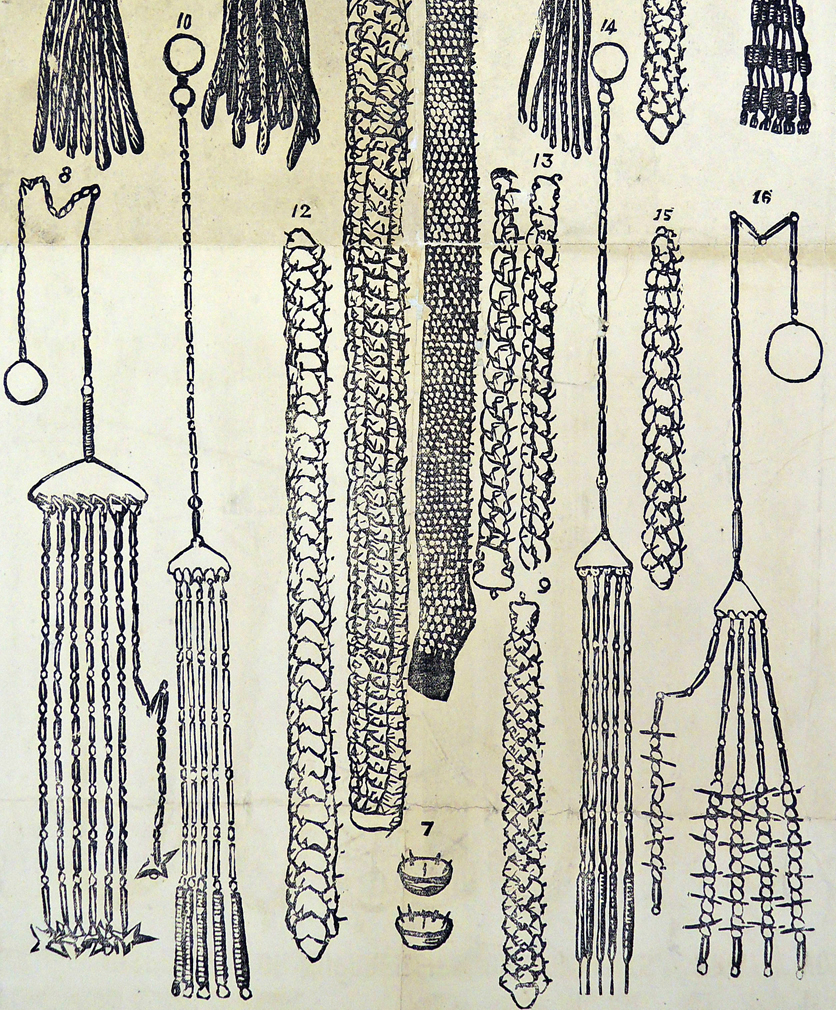

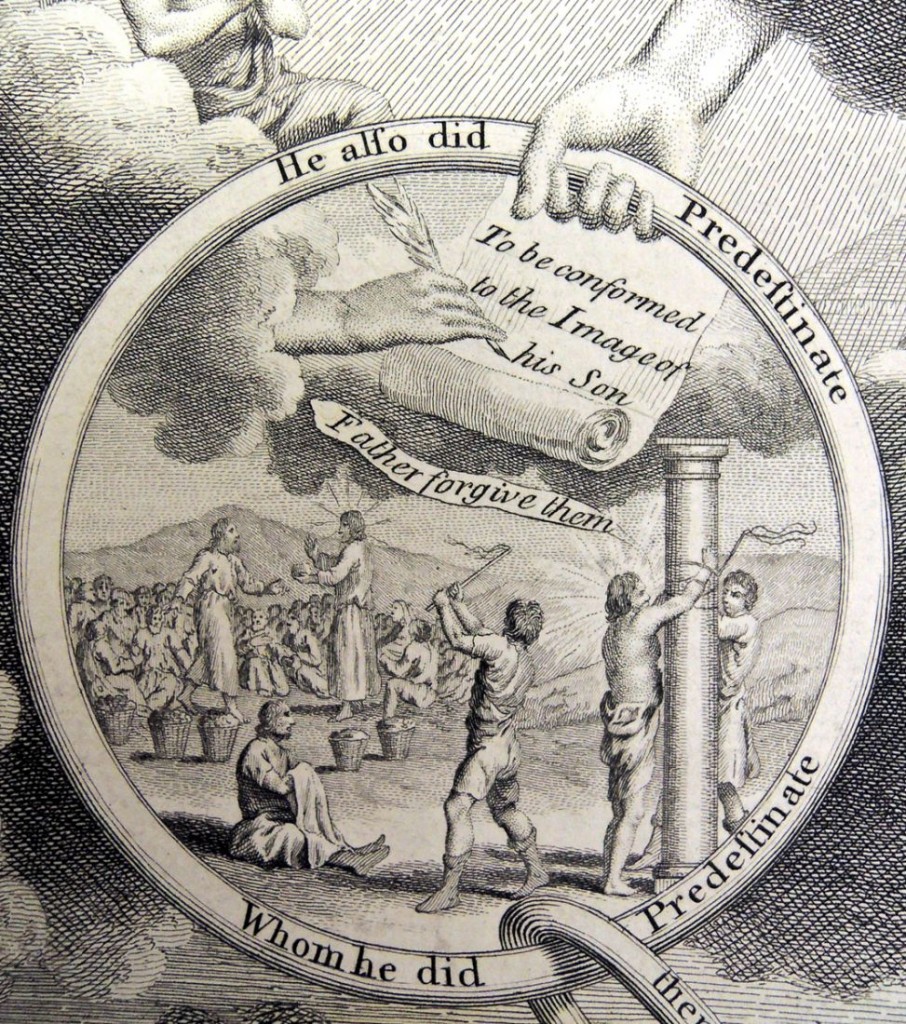

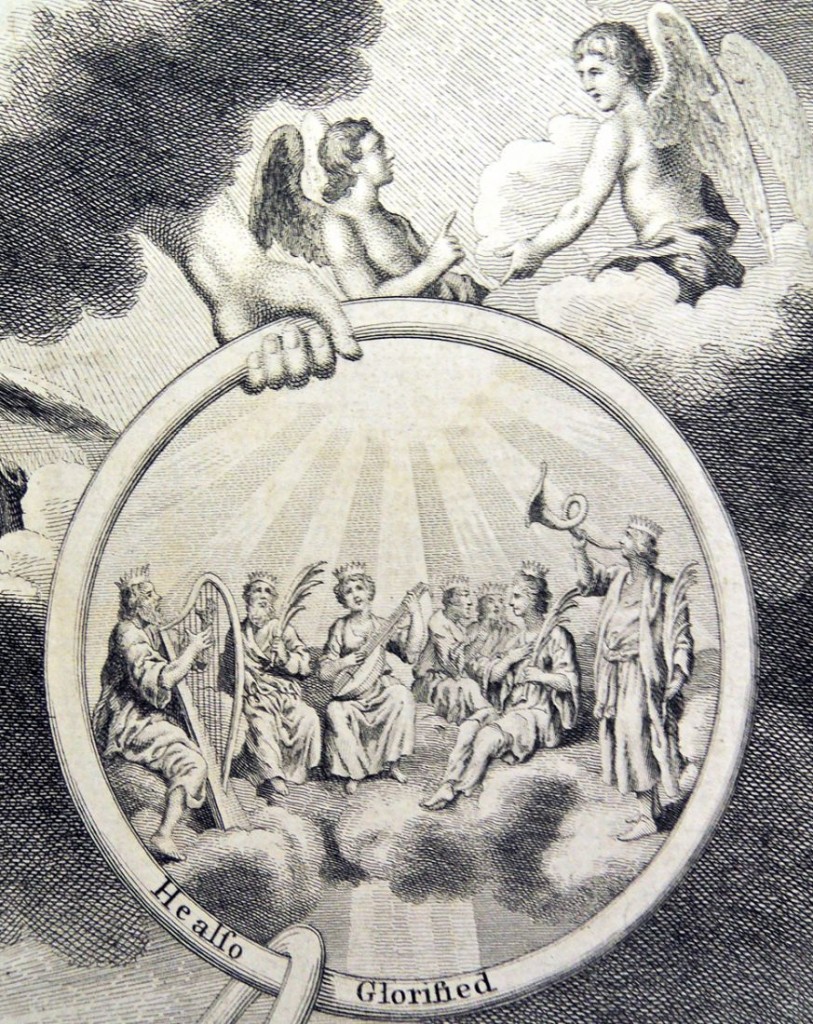

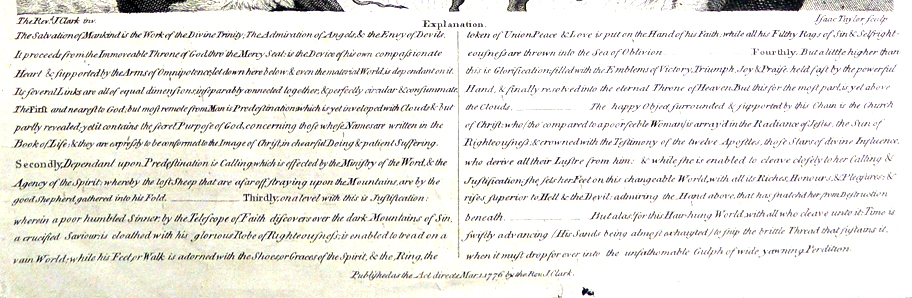

Copies of this Paper may be had Gratis for posting on Church and Chapel boards.

Copies of this Paper may be had Gratis for posting on Church and Chapel boards.