One of the most interesting small presses to come out of Paris in the 1920s was Hours Press, run by Nancy Cunard (1896-1965), with the assistance of Henry Crowder (1890-1955). Details about the press are recorded by Cunard herself in These were the Hours: memories of my Hours Press, Reanville and Paris, 1928-1931, edited with a foreword by Hugh Ford (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, [1969]).

One of the most interesting small presses to come out of Paris in the 1920s was Hours Press, run by Nancy Cunard (1896-1965), with the assistance of Henry Crowder (1890-1955). Details about the press are recorded by Cunard herself in These were the Hours: memories of my Hours Press, Reanville and Paris, 1928-1931, edited with a foreword by Hugh Ford (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, [1969]).

The British heiress was a popular jazz age beauty, well over six feet tall, she was sought after by many artists including Constantin Brancusi whose bronze sculpture La jeune fille sophistiquée (Portrait de Nancy Cunard) sold in 2018 for $71,000,000.

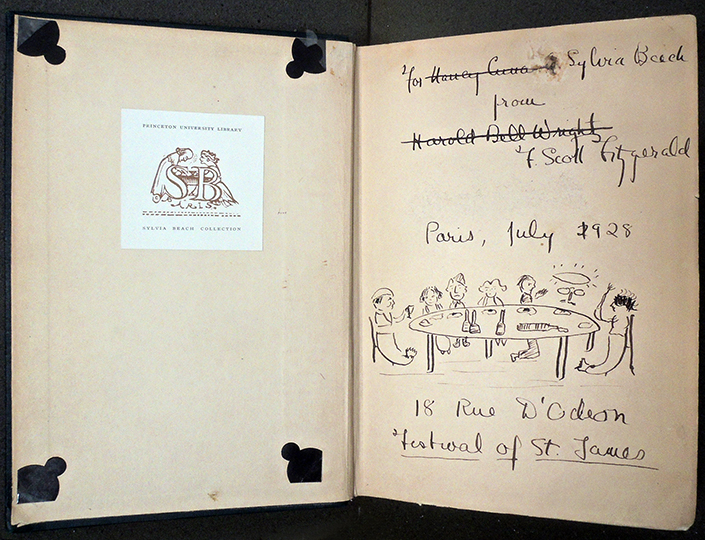

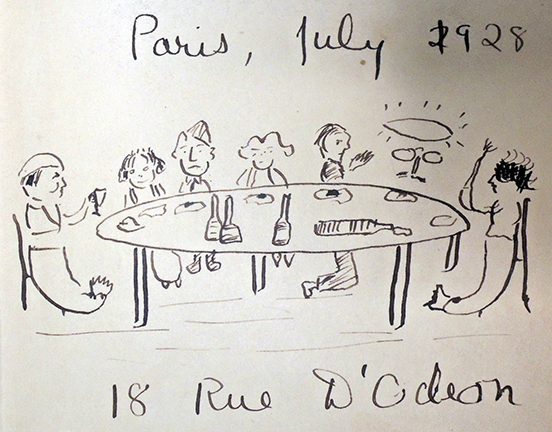

Cunard settled in Paris at the age of 24, where she published three volumes of poetry in quick succession: Outlaws in 1921, Sublunary in 1923, and Parallax in 1925. Convinced that she could print and publish her own books, Cunard left Paris in 1927 for a house in Réanville, Normandy. There she installed a 200-year-old Belgian Mathieu hand press purchased from Bill Bird of Three Mountains editions. It came with plenty of Caslon Old Face type and Vergé de Rives paper that she happily used for most of her early books. As a printer Cunard was chiefly self-taught although she had some lessons in setting type from Leonard and Virginia Woolf. Her imprint was to be called Hours Press, perhaps a suggestion from Virginia.

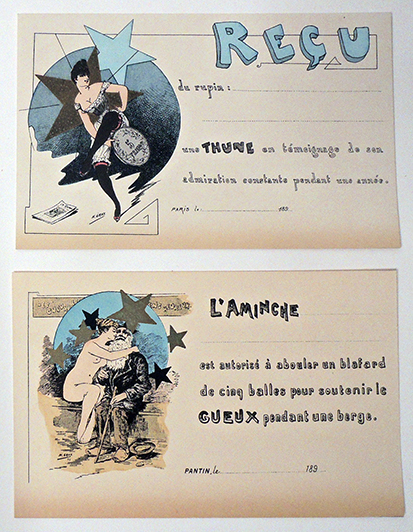

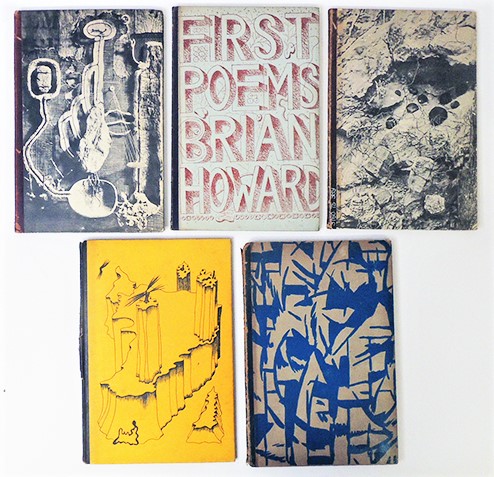

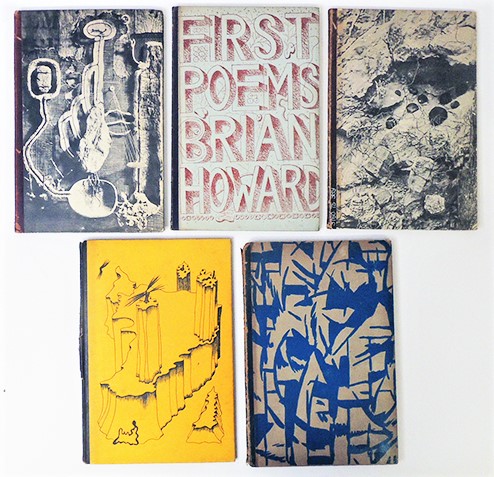

Front covers above. Back covers below.

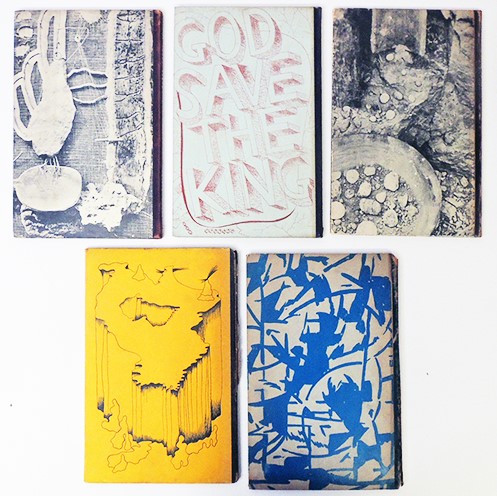

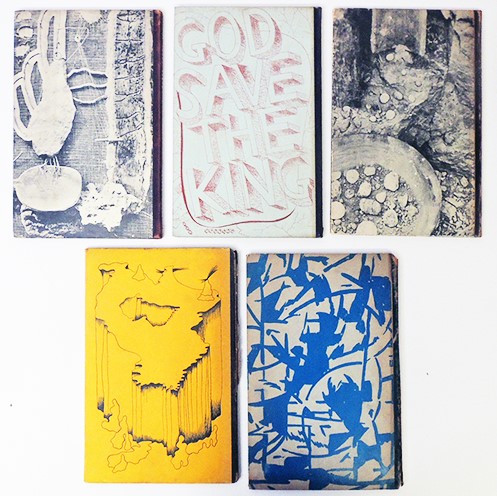

Front covers above. Back covers below.

Around this time, she also fell in love with Henry Crowder (1890-1955), a Black American jazz musician and lived with him for the next eight years, building the printshop together. “Henry Crowder, . . . had helped in many different ways already . . . Together we folded the sheets into pages as they came off the new Minerva press I had just bought to increase the tempo of our work.” Many friends offered to let Hours Press publish their manuscripts and artists such as Man Ray and Yves Tanguy agreed to design the covers.

In January 1930, they moved their home and printshop back to Paris where Crowder could both print and perform with his jazz band. Under his direction, they also worked on an anthology of African American writing to be called Negro, which soon became an obsession for Cunard. While vacationing in the south of France that summer, Cunard and Crowder turned over the management of the press to Mrs. Wyn Henderson and her young printer John Sibthorpe. This freed Cunard for research and travel to collect work for their anthology but eventually, she had to choose between projects. Hours Press was closed in early 1931 having completed 25 publications.

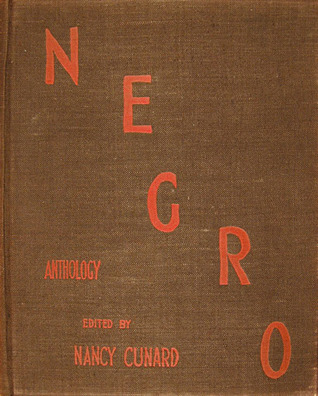

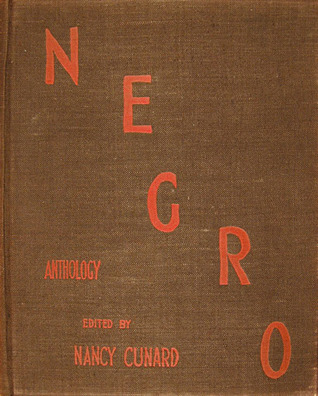

Cunard published her Negro anthology in 1934, collecting poetry, fiction, and nonfiction primarily by African-American writers, including Langston Hughes and Zora Neale Hurston along with writing by George Padmore and her own essay on the Scottsboro Boys.

Cunard published her Negro anthology in 1934, collecting poetry, fiction, and nonfiction primarily by African-American writers, including Langston Hughes and Zora Neale Hurston along with writing by George Padmore and her own essay on the Scottsboro Boys.

Hours Press books:

1928

Douglas, Norman. Report on the Punice-Stone Industry of the Lipari Islands. June 1928. 80 letterpress copies set in 11 pt. Caslon Old Face. Not for sale.

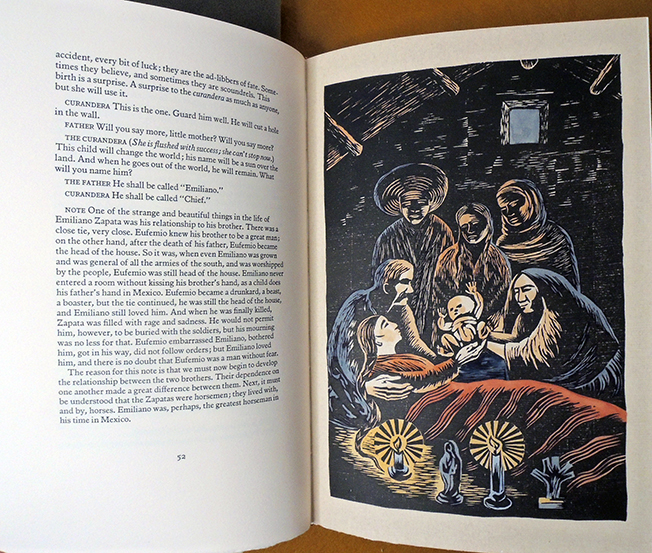

Moore, George. Peronnik the Fool. December 1928. 200 letterpress signed copies on Vergé de Rives paper set in 11 pt. Caslon Old Face. Sold for £2.

Aldington, Richard. Hark the Herald. December 1928. 100 letterpress signed copies on Vergé de Rives paper, set in 17 pt. Caslon Old Face. Mary blue wrappers. Not for sale.

1929

Guevara, Alvaro. St George at Silene. January 1929. 150 letterpress signed copies on Velin de Rives paper set in 16 pt. Caslon Old Face. Designed by the author. Sold for 10s, 6d.

Douglas, Norman. One Day. July 1929. 200 signed copies on Velin de Rives, set in monotype. Sold for 3 £3, 3 s. Also 300 copies, Vergé de Vidalon sold £1. 10s

Symons, Arthur. Mes Souvenirs. July 1929. 200 signed copies on Velin de Rives paper. Sold for £2, 2s.

Aragon, Louis. La Chasse au Snark. Early winter. 300 letterpress signed copies on Alfa paper set in 16 pt. Caslon Old Face. Title on front designed and composed by Aragon. Also 5 copies on Japan paper. 300 copies sold at £1. 1s; 5 copies at £5, 5s.

Aldington, Richard. The Eaten Heart. Late winter 1929. 200 letterpress signed copies on Canson-Montgolfier set in 16pt. Caslon Old Face. Sold for £1, 1s.

1930

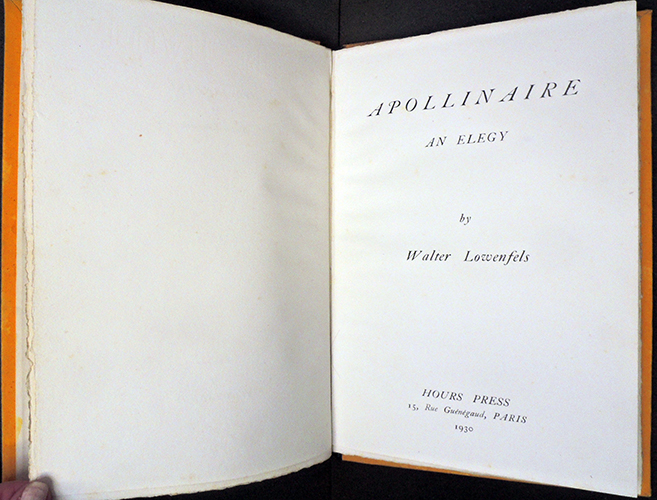

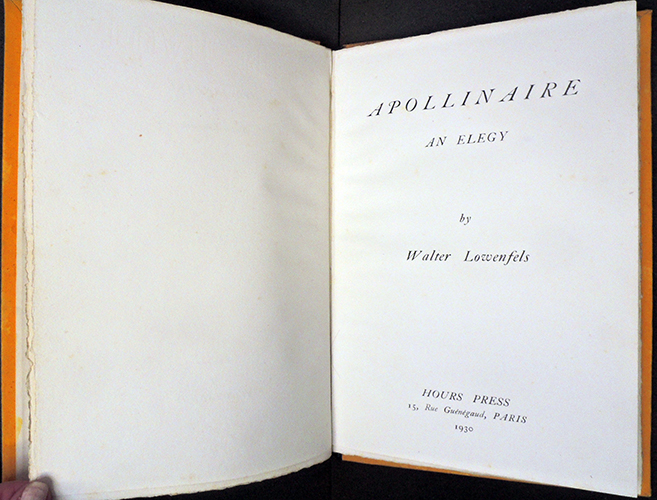

Lowenfels, Walter. Apollinaire. Early 1930. 150 copies signed letterpress copies on Canson-Montgolfier paper set in 16 pt. Caslon Old Face. Cover front and back designed by Yves Tanguy, printed black on daffodil paper boards. Sold for £1, 10s.

MacCown, Eugene. Catalogue of Paintings, Drawings, and Gouaches. Early 1930. 1000 copies set in Caslon old Face Italics on Vergé de Rives paper. Not for sale.

Graves, Robert. Ten Poems More. Early spring 1930. 200 signed letterpress copies on Canson-Montgolfier paper set in 16 pt Caslon Old Face. Cover photomontage by Len Lye. Sold for £1. 10s.

Riding, Laura. Twenty Poems Less. Spring 1930. 200 signed letterpress copies on Canson-Montgolfier paper set in 16 pt. Caslon Old Face. Front and back cover photomontage designed by Len Lye. Sold for £1. 10s.

Riding, Laura. Four Unposted Letters to Catherine. Early summer. 200 signed copies on Haut Vidalon paper set in Garamond Italic type. Front and back cover photomontage by Len Lye. Sold for £2.

Campbell, Roy. Poems. July 1930. 200 letterpress signed copies on Canson-Montgolfier paper set in 16 pt. Caslon Old Face. Two drawings by the author. Sold for £1. 10s.

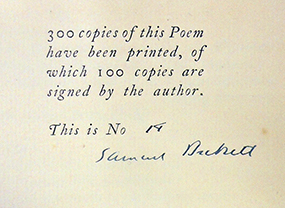

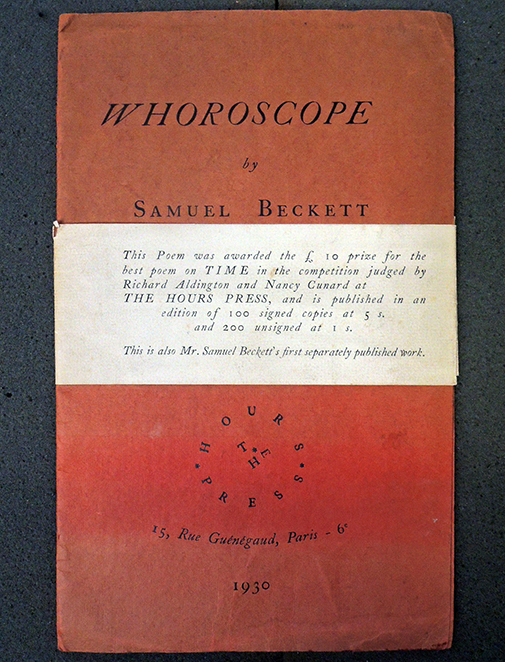

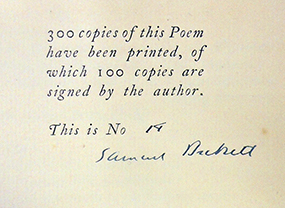

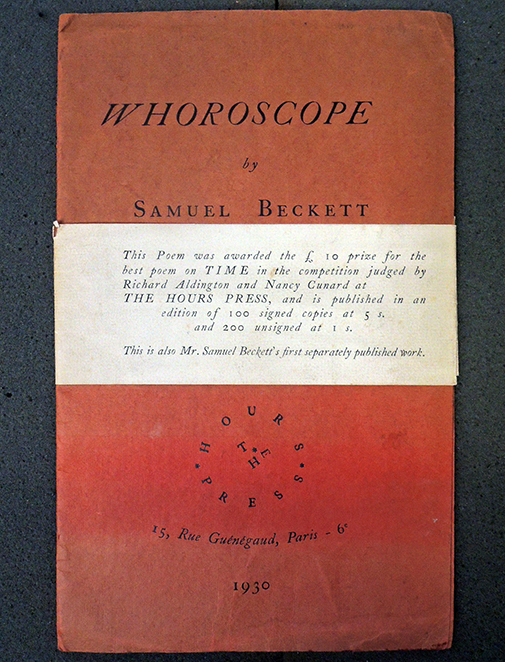

Beckett, Samuel. Whoroscope. Midsummer 1930. 100 signed letterpress copies and 200 not signed, both on Vergé de Rives paper set in 11 pt. Caslon Old Face. Won £10 prize for the best poem on ‘Time.’ Signed sold for 5s; not signed sold for 1s.

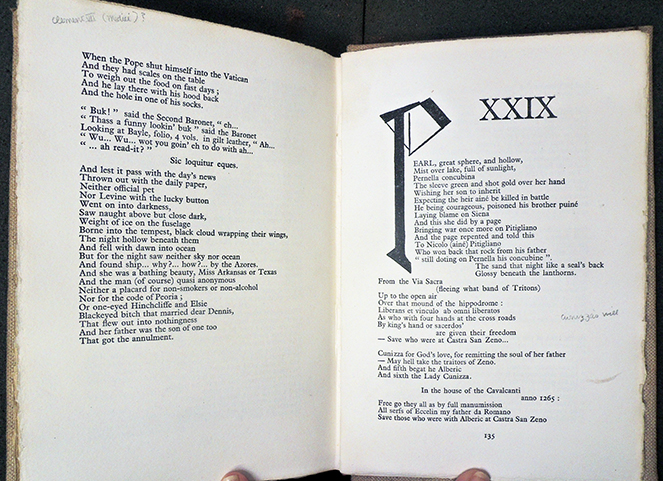

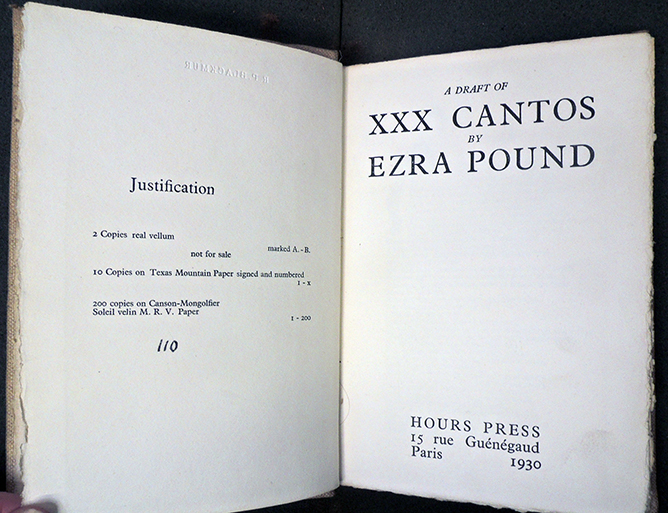

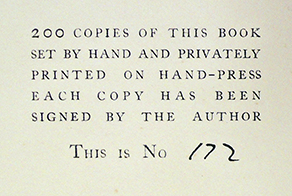

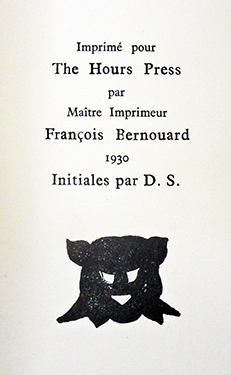

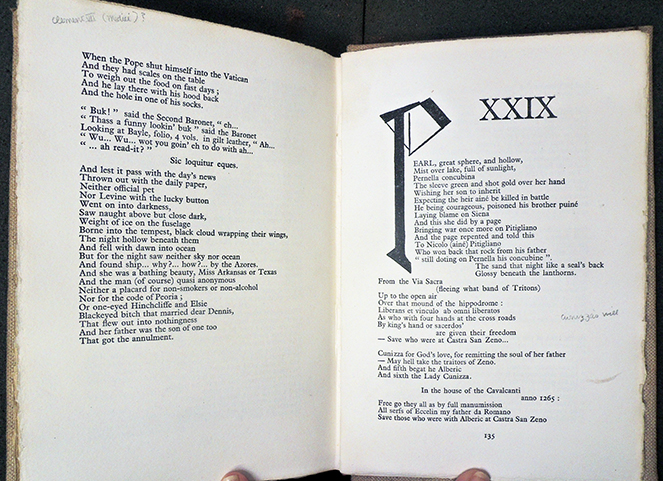

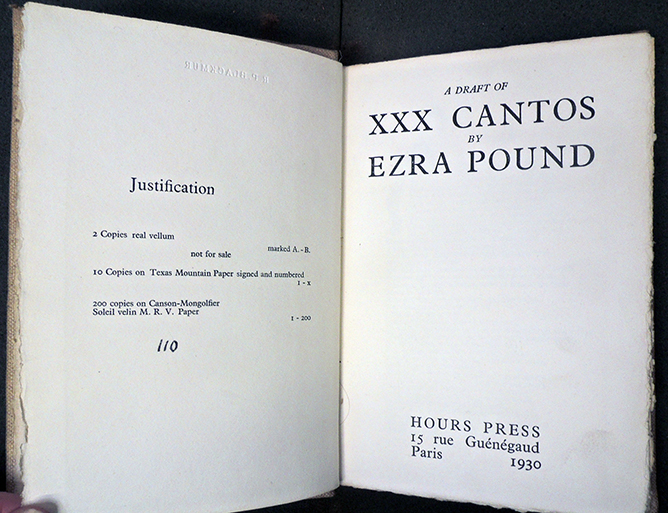

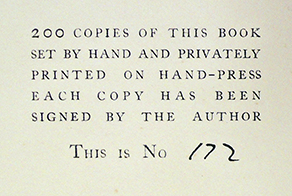

Pound, Ezra. A Draft of XXX Cantos. Midsummer 1930. 200 copies not signed on Canson-Montgolfier-Soleil Velin paper and 10 signed (2 of these on vellum) on Texas Mountain paper bound in red leather. Initial letters by Dorothy Shakespear (wife of Pound). 200 copies sold for £2; 10 copies sold for £5, 5s.

Rodker, John. Collected Poems. August 1930. 200 signed copies hand-made paper. Initial lettering by Edward Wadsworth. Front and back cover photomontage by Len Lye. Sold for £1, 10s.

Crowder, Henry. Henry-Music. December 1930. 150 copies signed. Cover photomontage by Man Ray. Sold for 10s, 6d.

1931

Acton, Harold. This Chaos. January 1931. 150 letterpress signed copies on Canson-Montgolfier paper set in 16 pt. Caslon Old Face. Front and back cover designed and printed in blue by

Elliott Seabrooke. Sold for £1, 10s.

Aldington, Richard. Last Straws. January 1931. 200 signed copies in green suede cloth boards. 300 not signed copies in grey-brown paper boards. Designed by Douglas Cockerell. Signed copies sold for £2; unsigned copies sold for 7s, 6d.

Howard, Brian. First Poems. January 1931. 150 signed letterpress copies on Canson-Montgolfier paper set in 16 pt. Caslon Old Face. Covers designed by John Banting. Sold for £1. 10s.

Brown, Bob. Words. January 1931. 150 signed letterpress copies on Canson-Montgolfier paper set in 16 pt. Caslon Old Face. Upper cover designed by John Sibthorpe. Sold for £1, 10s.

Moore, George. The Talking Pine. Early 1931. 500 copies. Not for sale.

Ellis, Havelock. The Revaluation of Obscenity. Spring 1931. 200 signed copies. Blue cloth boards. Sold for £2.

See: https://www.the-tls.co.uk/articles/more-than-a-muse-nancy-cunard/