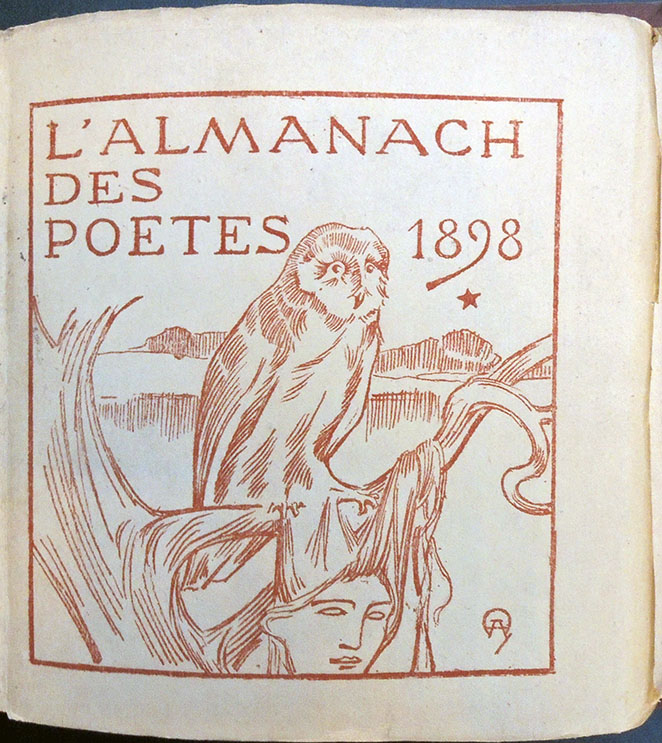

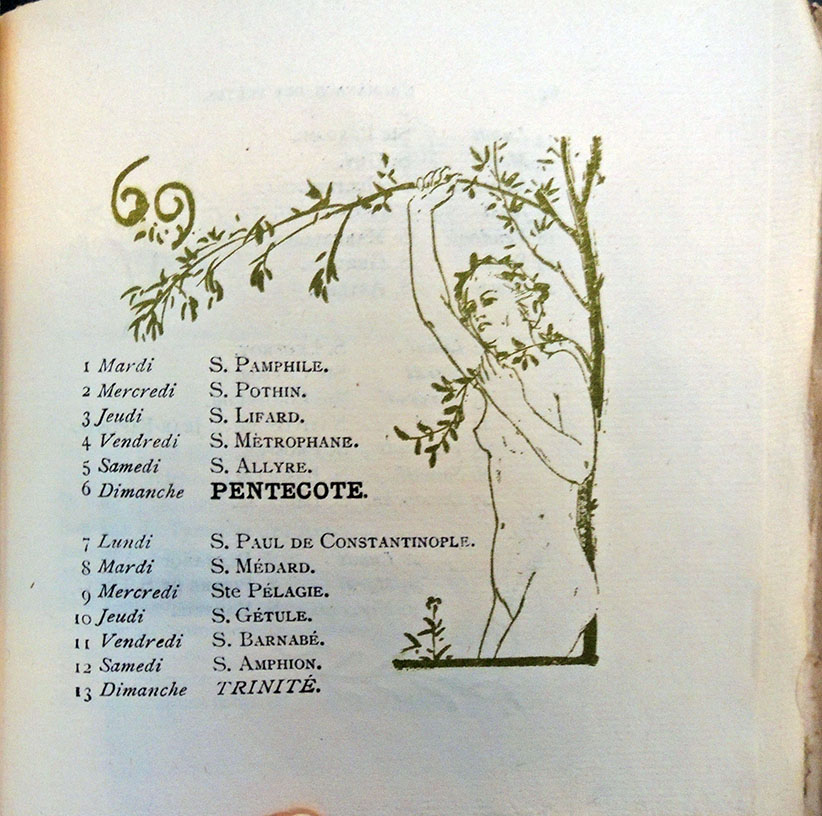

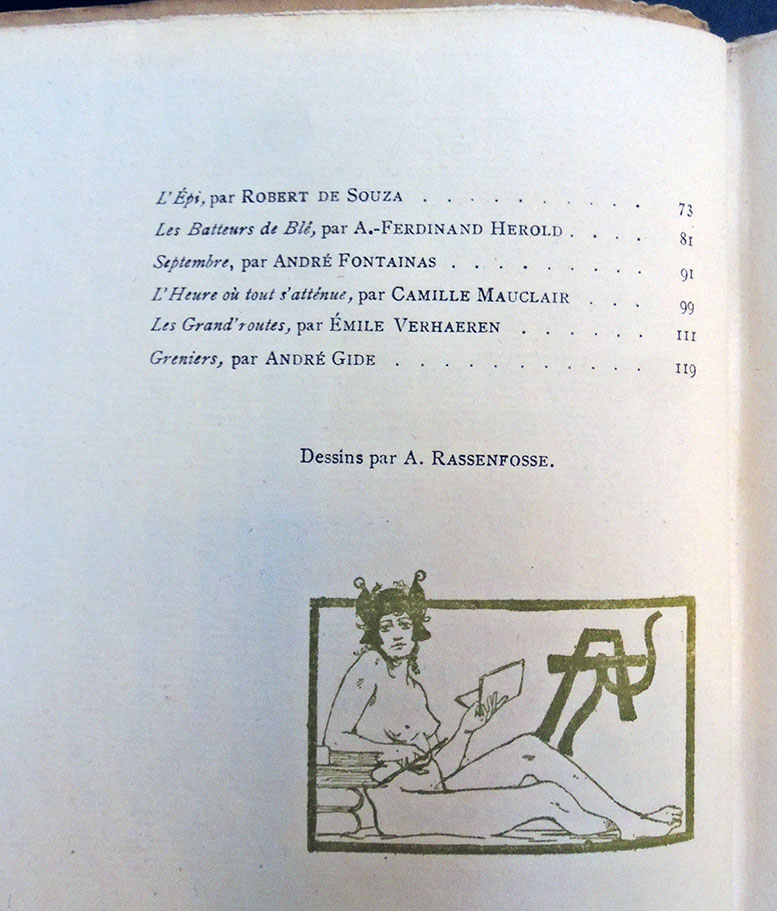

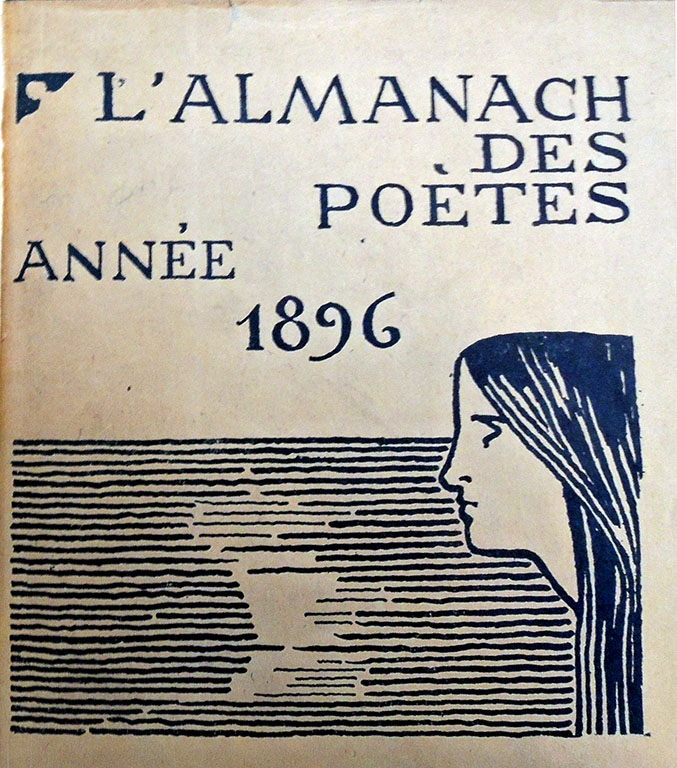

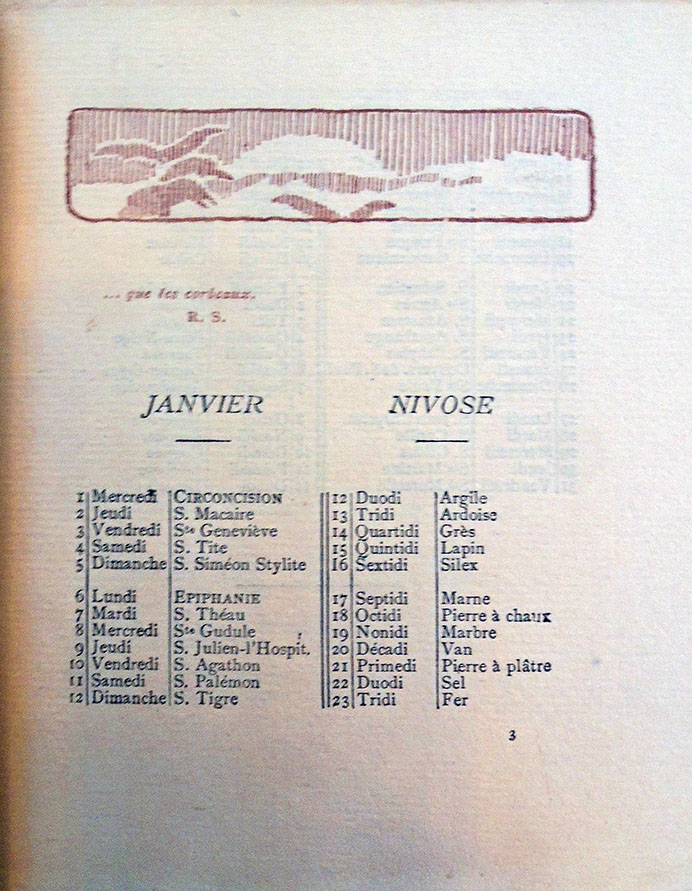

L’Almanach des poètes pour l’année ... (Paris: Edition du Mercure de France, 1896-1898). Volumes for 1896 and 1898 illustrated by Auguste Donnay; for 1897 by A. Rassenfosse. The editor for the series is R. de Souza. Graphic Arts Collection PQ1163 .A463 in process

L’Almanach des poètes pour l’année ... (Paris: Edition du Mercure de France, 1896-1898). Volumes for 1896 and 1898 illustrated by Auguste Donnay; for 1897 by A. Rassenfosse. The editor for the series is R. de Souza. Graphic Arts Collection PQ1163 .A463 in process

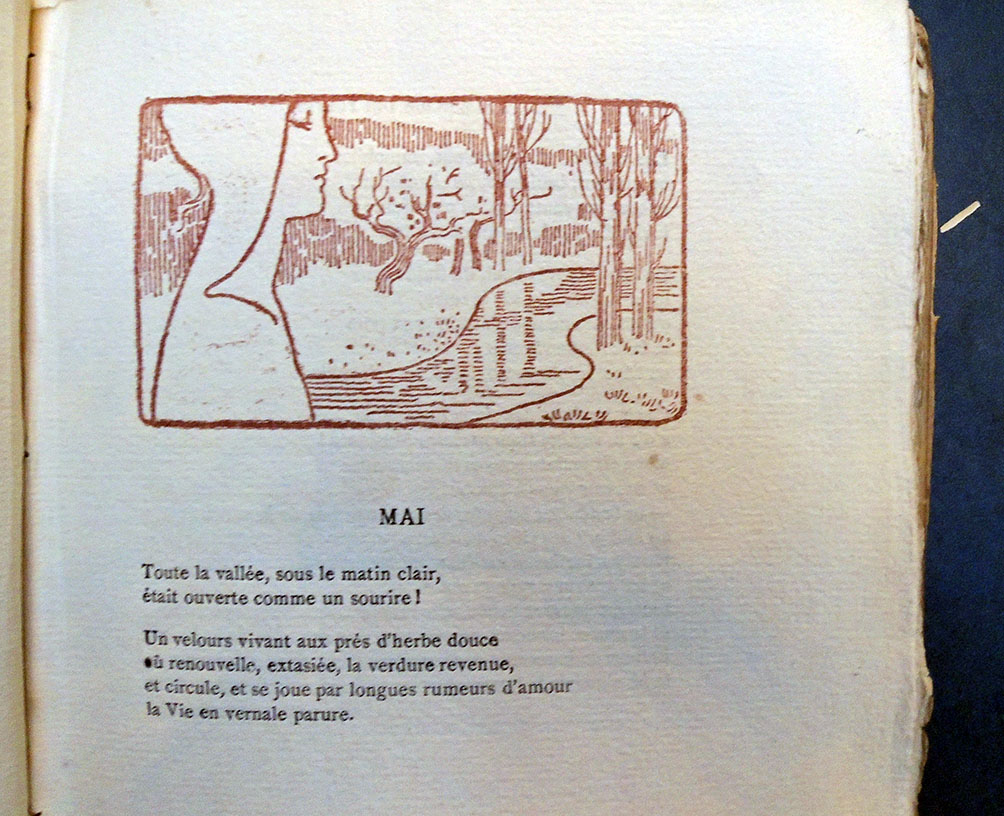

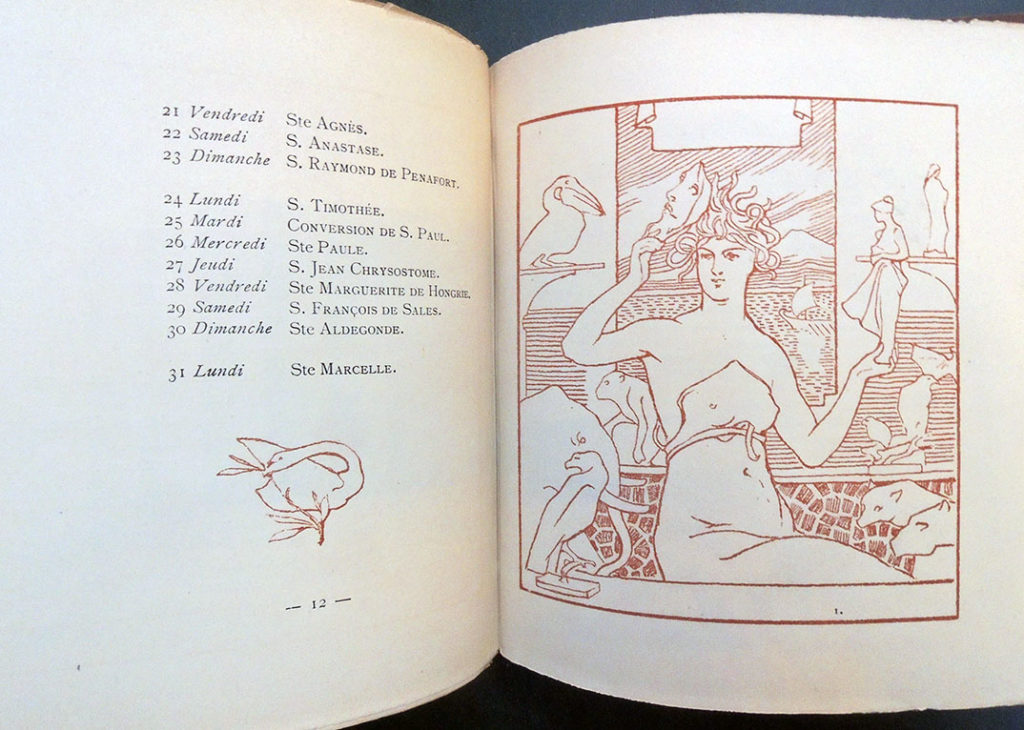

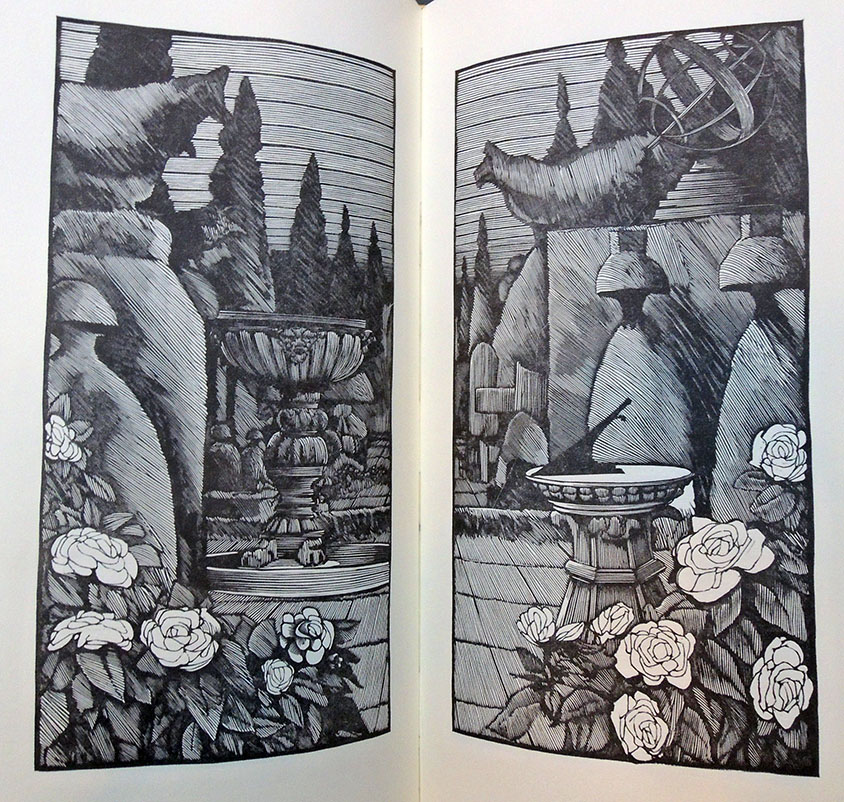

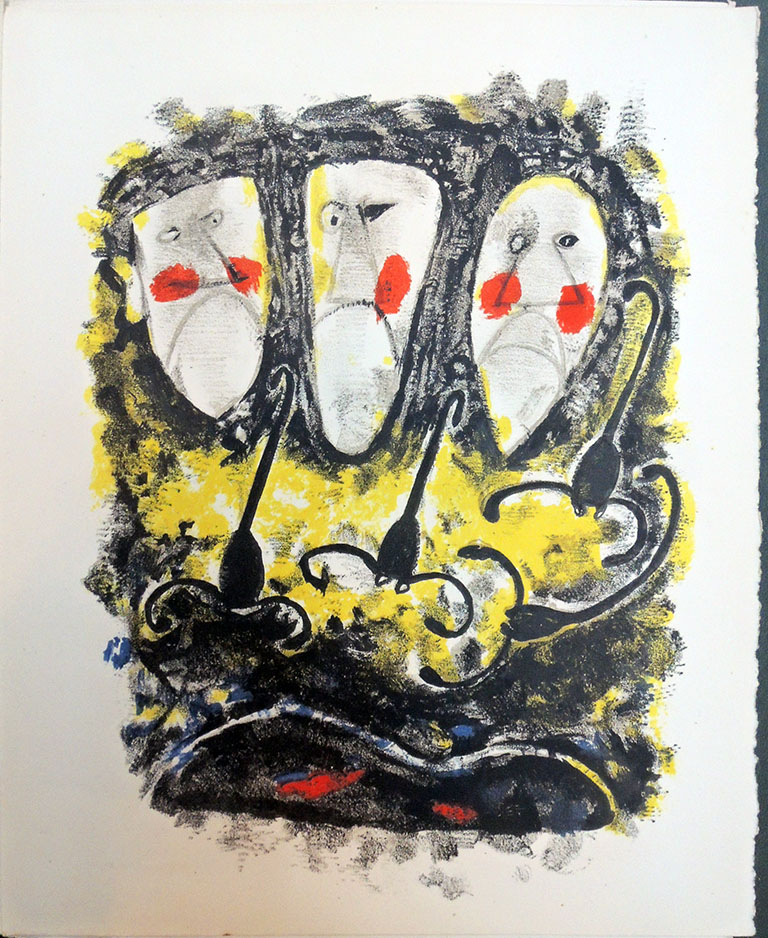

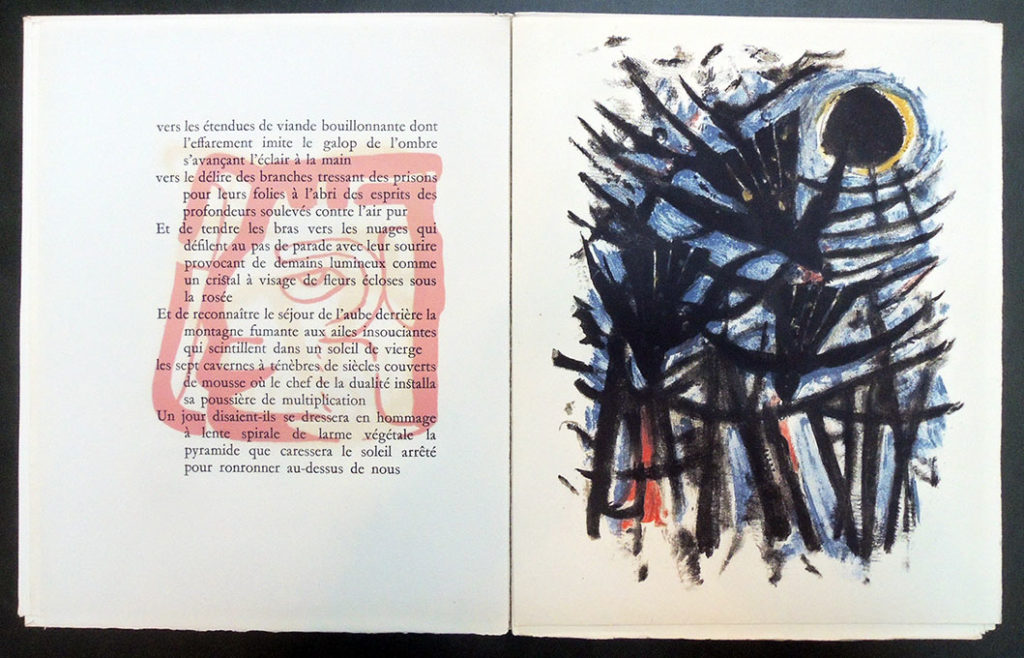

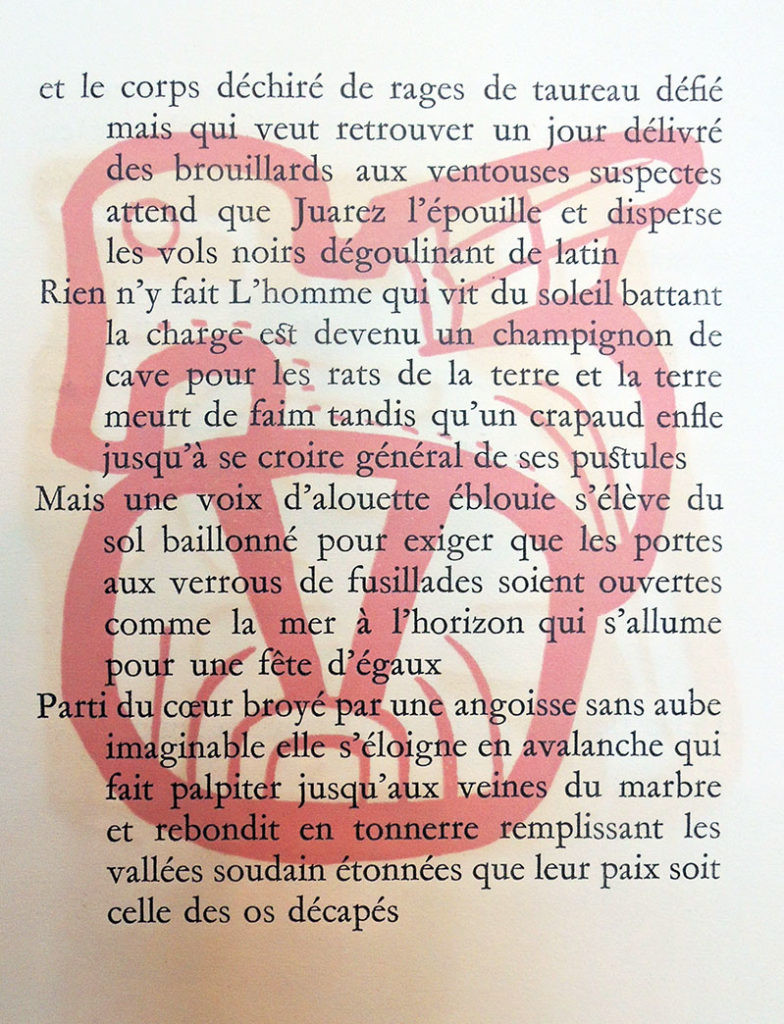

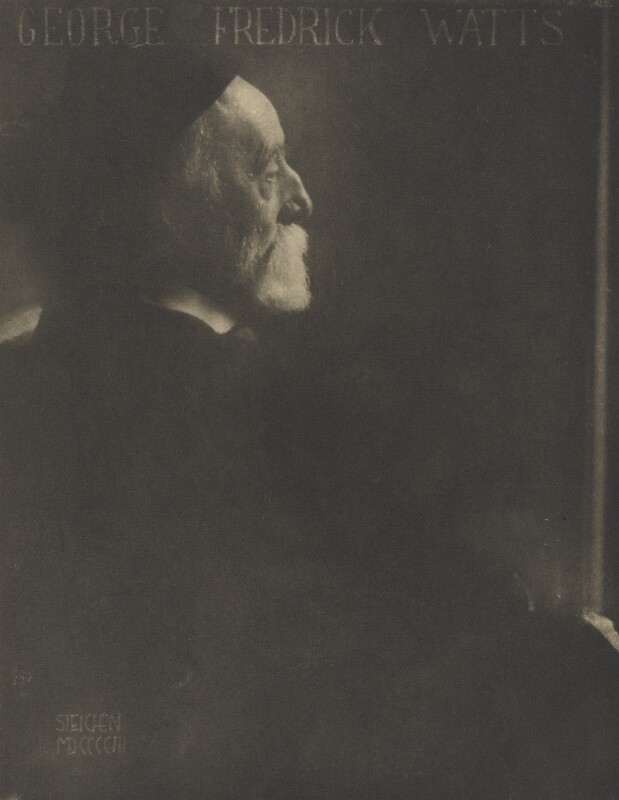

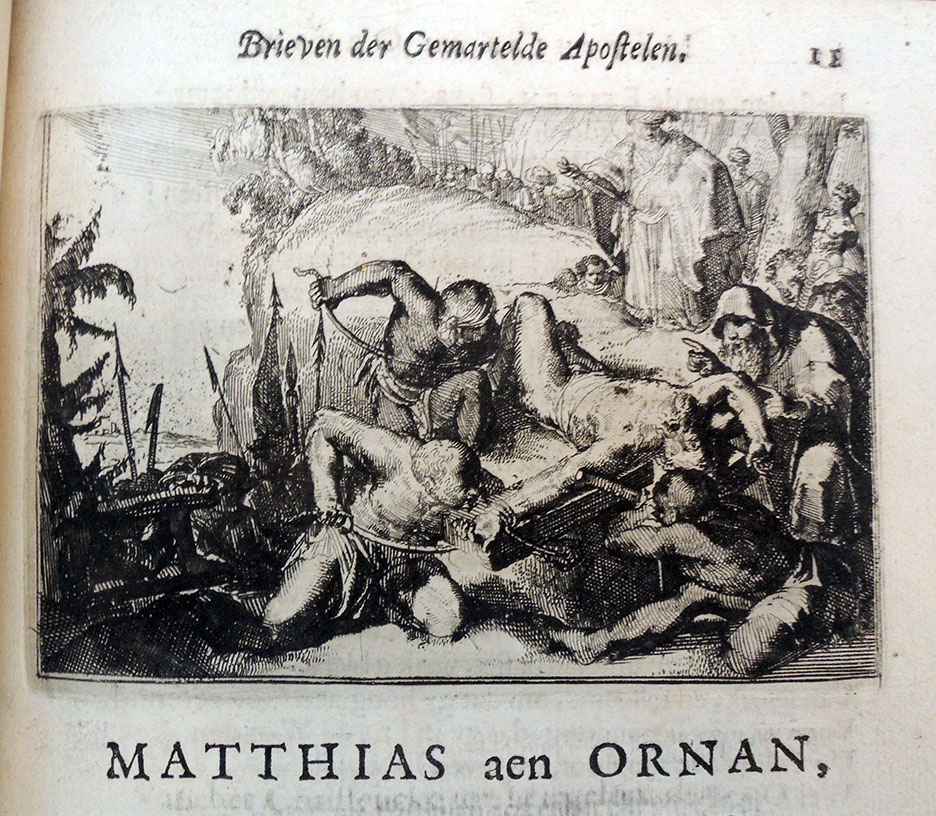

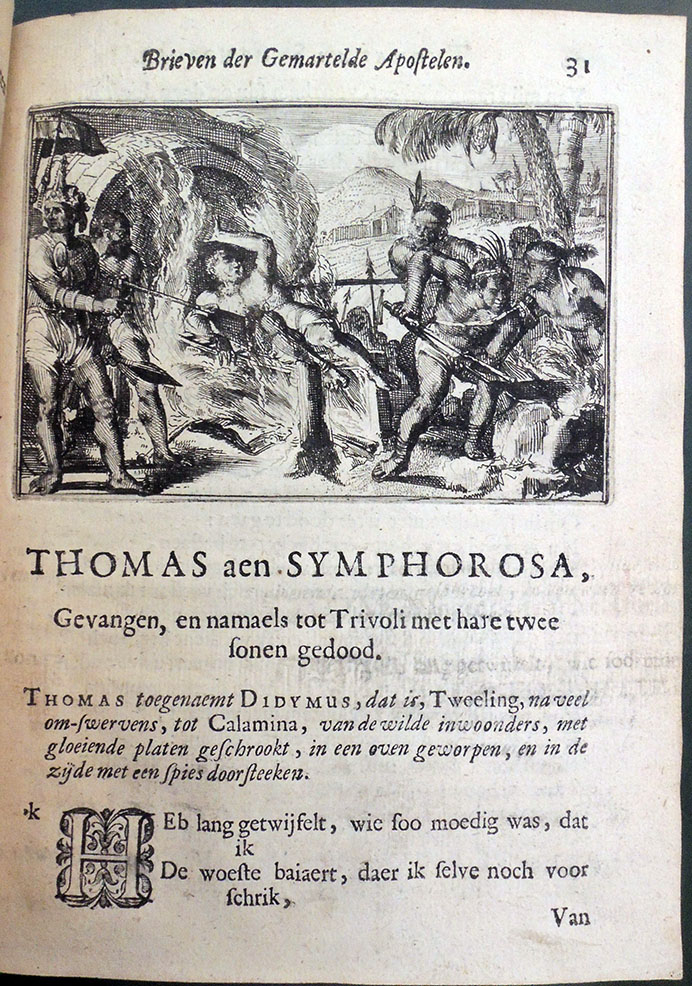

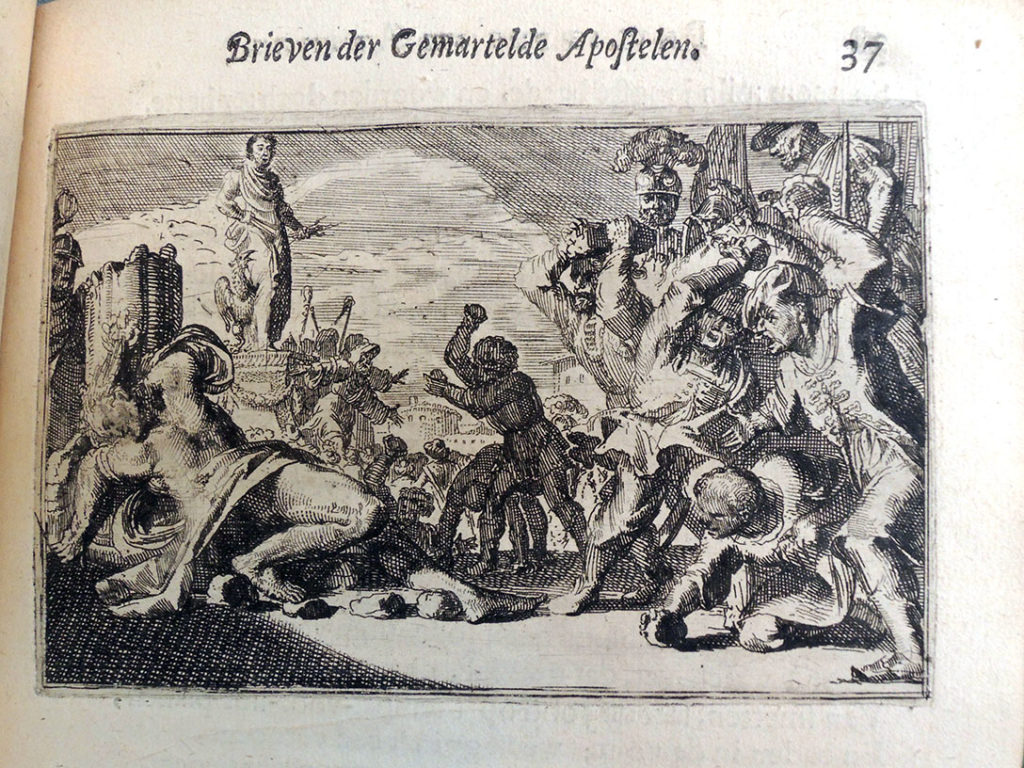

These rare fin-d-siècle almanacs were designed by the Belgian artists Auguste Donnay (1862-1921) and A. [André] Rassenfosse (1862-1934) under the watchful supervision of poet and editor Robert de Souza (1864-1946), a disciple of Stéphane Mallarmé. Small and unassuming, they include poems by such celebrated authors as André Gide, Gustave Kahn, Henri de Regnier, Emile Verhaeren, Stuart Merrill, Camille Mauclair, and many others.

These rare fin-d-siècle almanacs were designed by the Belgian artists Auguste Donnay (1862-1921) and A. [André] Rassenfosse (1862-1934) under the watchful supervision of poet and editor Robert de Souza (1864-1946), a disciple of Stéphane Mallarmé. Small and unassuming, they include poems by such celebrated authors as André Gide, Gustave Kahn, Henri de Regnier, Emile Verhaeren, Stuart Merrill, Camille Mauclair, and many others.

Benezit Dictionary of Art mentions that as a young artist Donnay spent “five months in Paris, where he got to know the Nabis. However, he was particularly attracted to Egyptian statuary, Japanese art and the Italian primitives, before he discovered the work of Puvis de Chavannes.

In 1894 he participated in the first Salon de la Libre Esthétique, and in 1896 he took part in the Salon de l’Art Indépendant in Paris. In 1901 he was appointed to teach at the Académie de Liège and gave lessons in ornamental composition. He left Liège in 1905 and went to live in Méry-sur-Ourthe.” Donnay was equally interested in art and poetry, illustrating many books and magazines throughout his life, including the issues of this Almanach.

Rassenfosse was the same age as Donnay and involved with many of the same people and projects. He spent time in Paris and became friends with Félicien Rops, together perfecting ‘Ropsenfosse,’ a soft varnish for paintings. By 1934, he was appointed the director of Fine Arts at the Belgian Académie Royale des Beaux Arts.

See also: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=gri.ark:/13960/t8hf0gd5q;view=thumb;seq=1