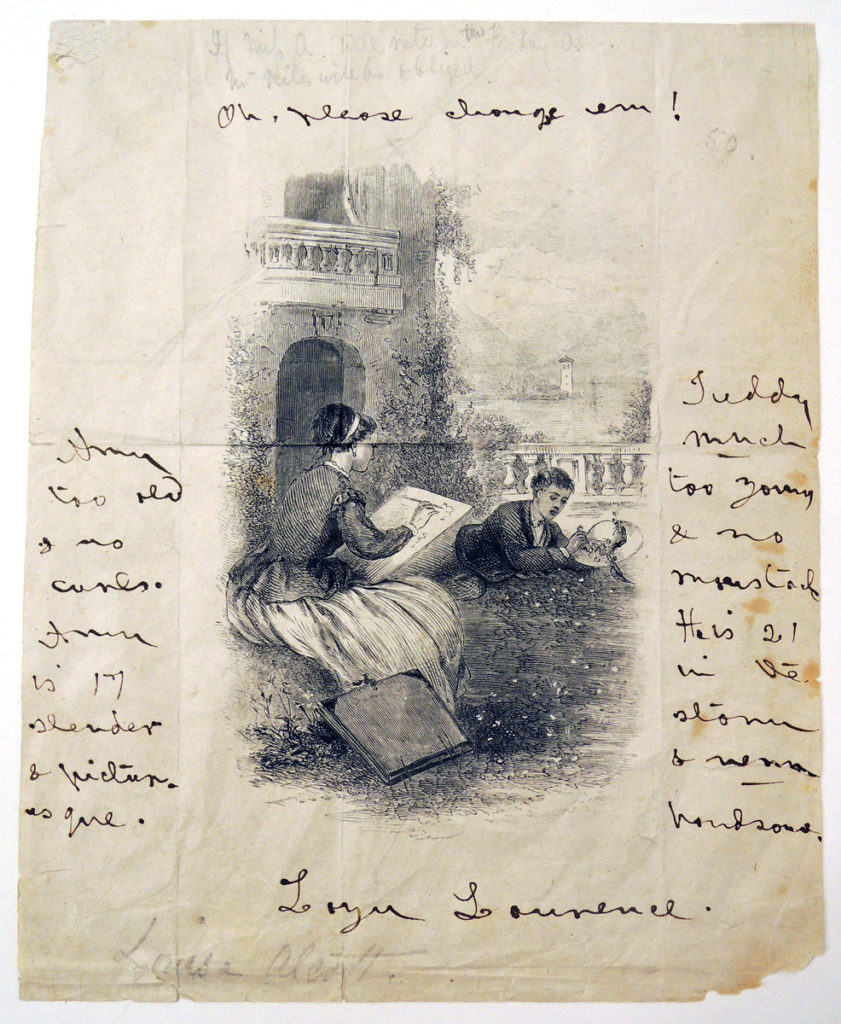

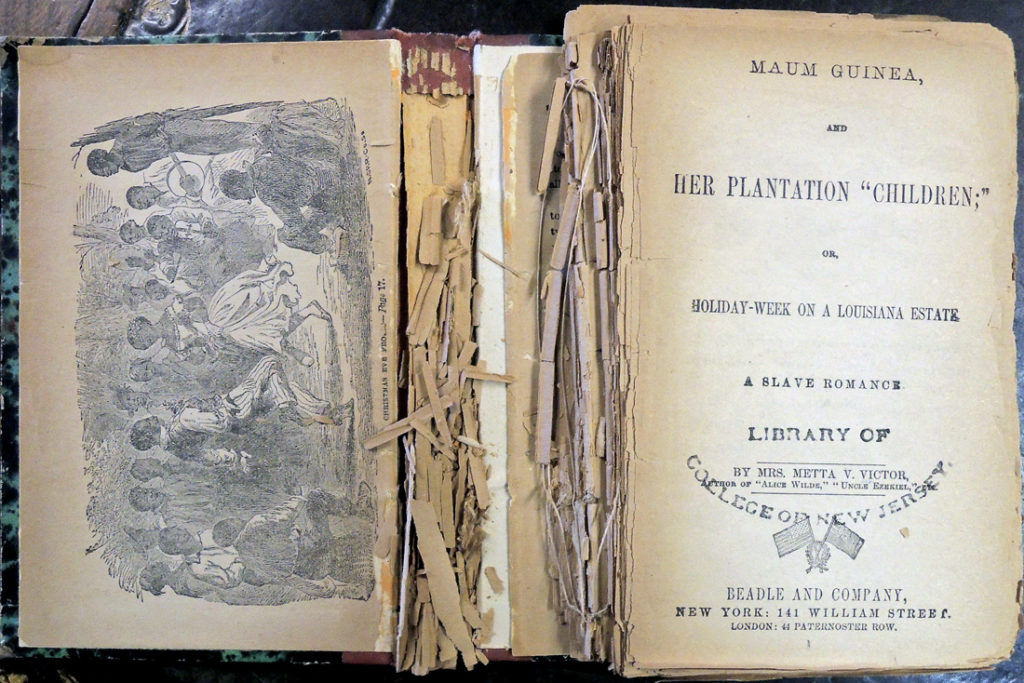

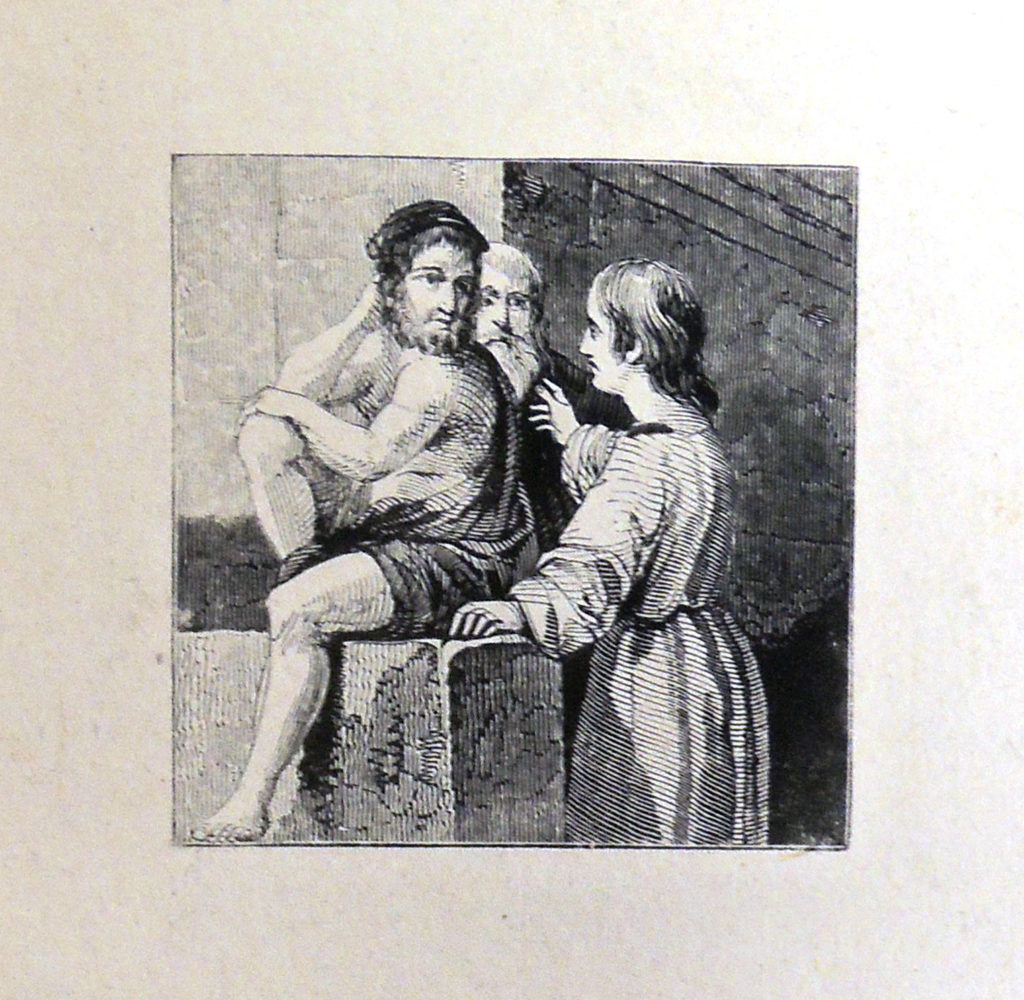

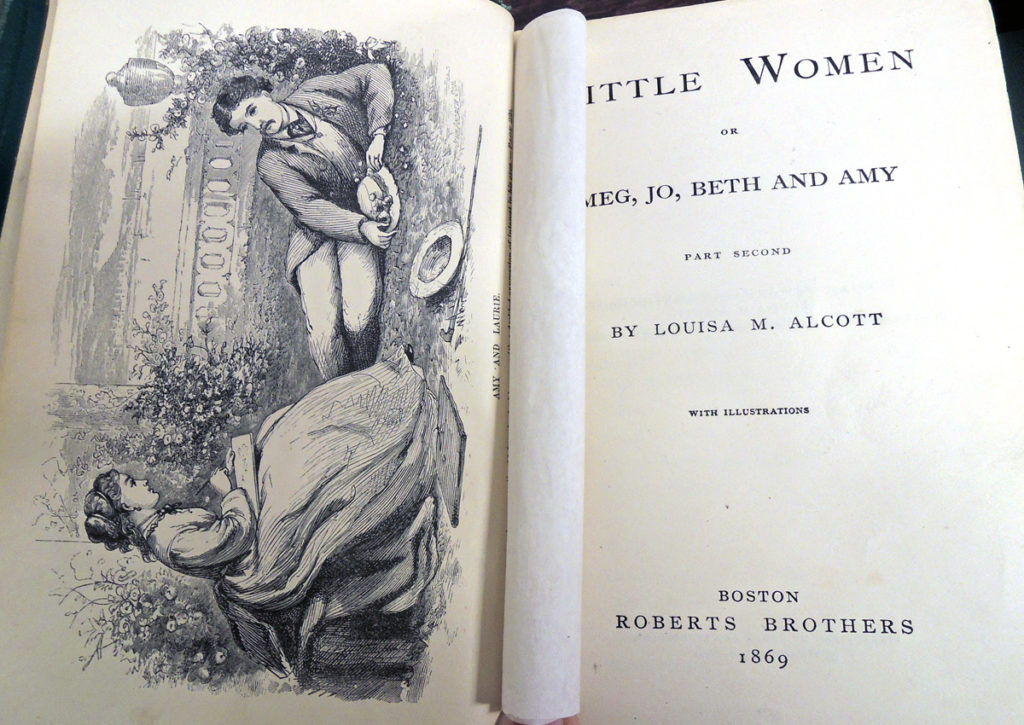

The Graphic Arts Collection holds a proof of a wood engraving after a drawing by Hammatt Billings (1818-1874), which Billings intended as the frontispiece to the Second Part of Little Women. As the collector Sinclair Hamilton notes, Louisa May Alcott (1832-1888) disliked it intensely, as is made evident by her letter to Elizabeth B. Greene:

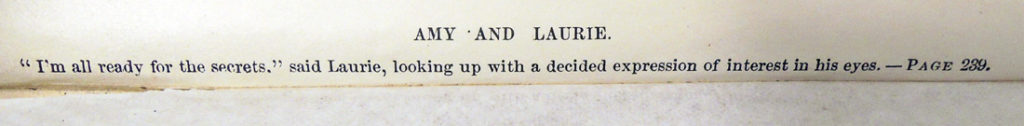

“Oh, Betsy! Such trials as I have had with that Billings no mortal creter [sic] knows! He went & drew Amy a fat girl with a pug of hair, sitting among weedy shrubbery with a lighthouse under her nose, & a mile or two off a scrubby little boy on his stomach in the grass looking cross, towzly, & about 14 years old! It was a blow, for that picture was to be the gem of the lot. I bundled it right back & blew Niles [of Roberts Brothers] up to such an extent that I thought he’d never come down again. But he did, oh bless you, yes, as brisk & bland as ever, & set Billings to work again. You will shout when you see the new one for the man followed my directions & made (or tried to) Laurie ‘a mixture of Apollo, Byron, Tito & Will Green.’ Such a baa Lamb! Hair parted in the middle, big eyes, sweet nose, lovely mustache & cunning hands; straight out of a bandbox & no more like the real Teddy than Ben Franklin. I wailed but let go for the girls are clamoring & the book can’t be delayed. Amy is pretty & the scenery good but—my Teddy, oh my Teddy!”

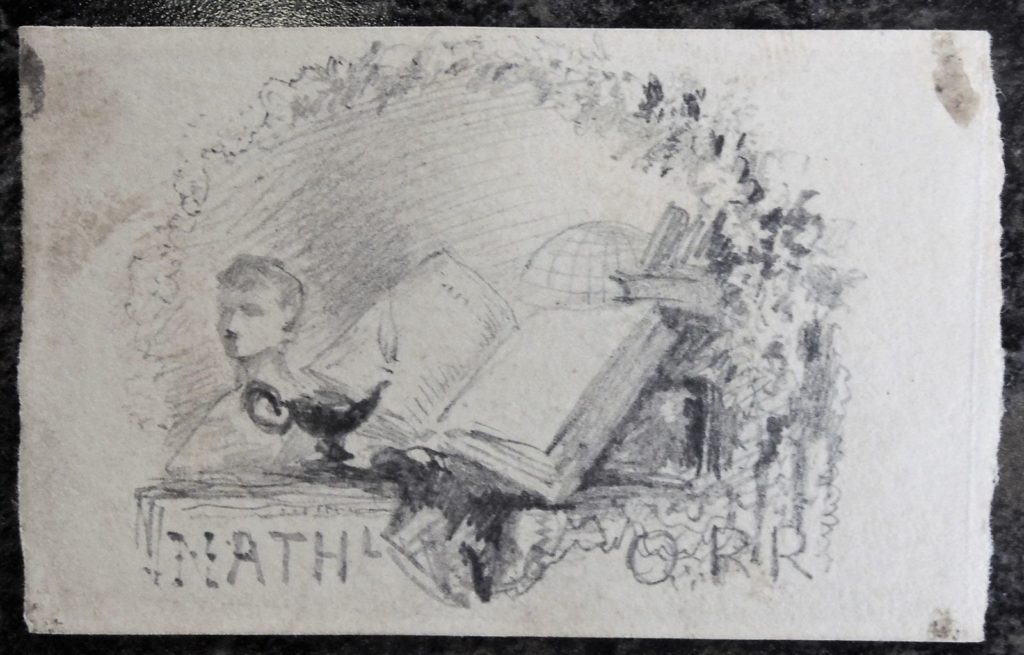

At the top of the proof is a penciled note from the publishers: “If Miss A. will return this Friday A.M. Mr. Niles will be obliged.” Under this, in ink, in Miss Alcott’s handwriting is written “Oh, please change em!” and, on the sides of the engraving, also in her handwriting, are the words: “Amy too old & no curls. Amy is 17, slender & picturesque. Teddy much too young and no mustache. He is 21 in the story & very handsome.”

At the bottom of the engraving Miss Alcott has written “Lazy Laurence.”

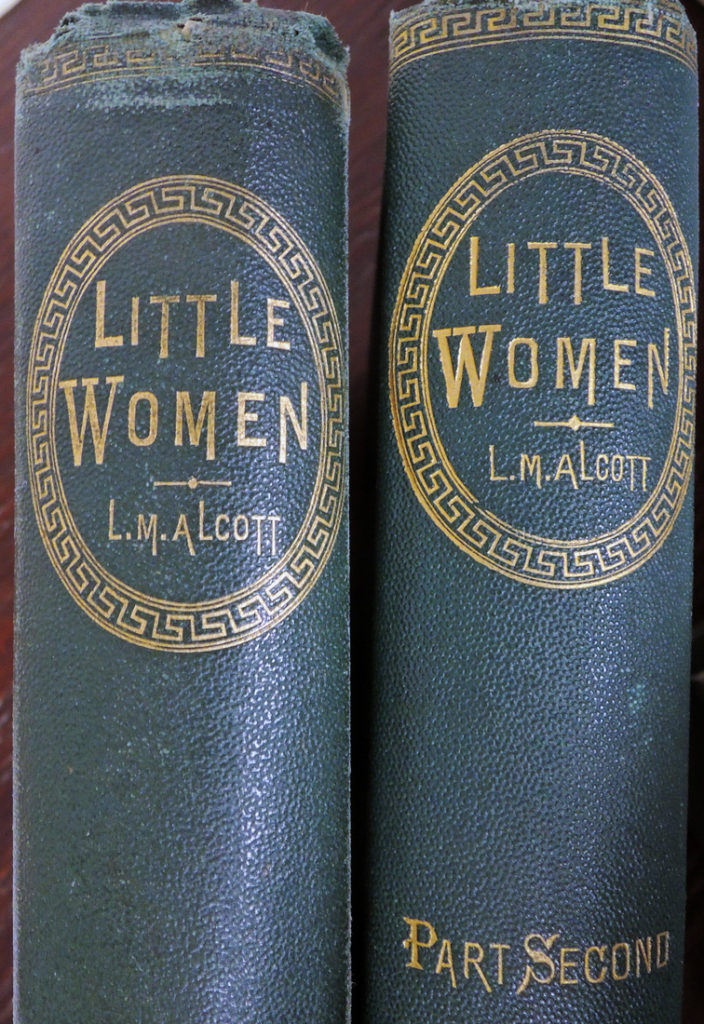

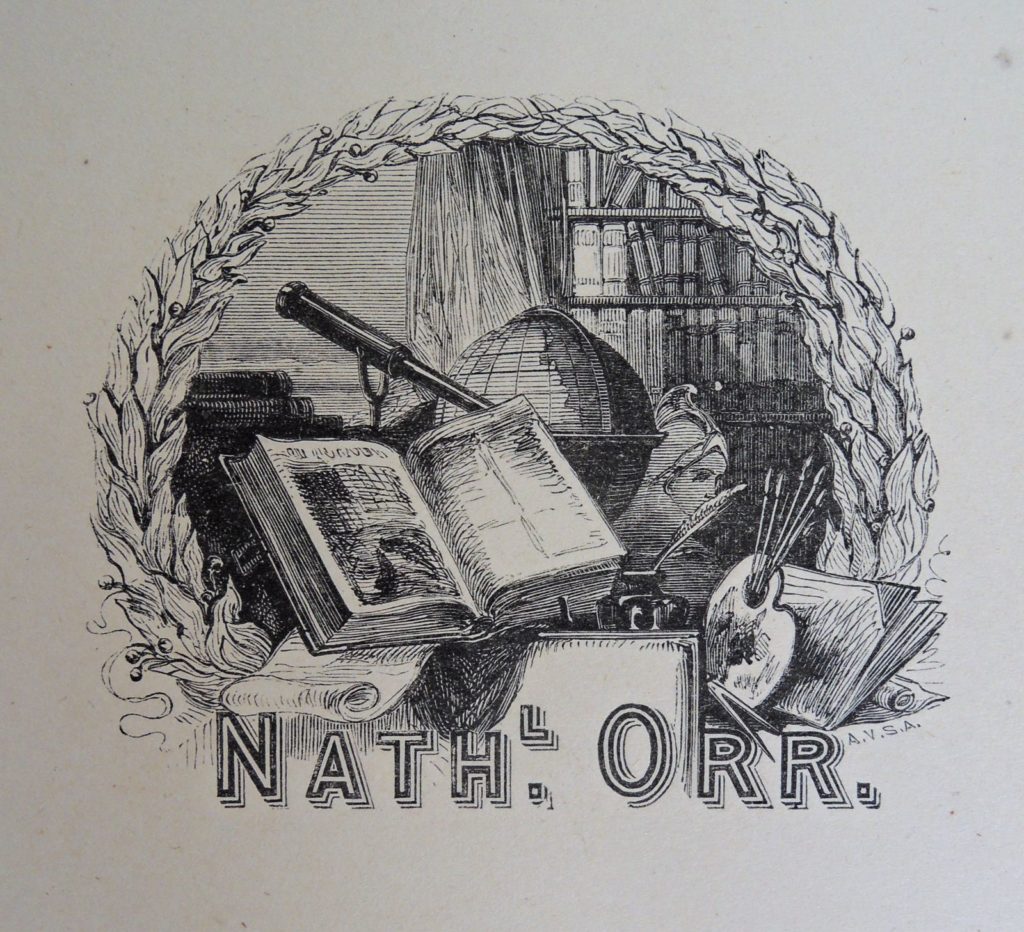

Hamilton’s second attempt is the one found as the frontispiece to “Part Second” of Little Women.

Hamilton’s second attempt is the one found as the frontispiece to “Part Second” of Little Women.

Louisa May Alcott (1832-1888), Little Women, or, Meg, Jo, Beth, and Amy. Part second (Boston: Roberts Brothers, 1869). Graphic Arts Collection (GAX) Hamilton 206(2)

Thanks to Ananya A. Malhotra, Class of 2020, for her help in locating this on her last day in RBSC.