Born on December 19, 1887, in LeRoy, New York (southwest of Rochester), surprisingly little is known about the American artist Charles Cullen. Here are a few more details. His father, Matthew Cullen, was born in Ireland in 1854 and moved to New York where he married a Canadian-born girl named Ellen. As the sixth of seven children, Charles was nearly 5-years-old when the family moved to Adelphi Street in Brooklyn so his father could take a job as an engineer. “Tall and blond with blue eyes” was what his WWI draft card said, excusing him from service due to poor eye sight. By 1917, he was living on East 31st Street, working as an artist at 1441 Broadway, possibly making designs the Hartford Textile Company in that building.

Born on December 19, 1887, in LeRoy, New York (southwest of Rochester), surprisingly little is known about the American artist Charles Cullen. Here are a few more details. His father, Matthew Cullen, was born in Ireland in 1854 and moved to New York where he married a Canadian-born girl named Ellen. As the sixth of seven children, Charles was nearly 5-years-old when the family moved to Adelphi Street in Brooklyn so his father could take a job as an engineer. “Tall and blond with blue eyes” was what his WWI draft card said, excusing him from service due to poor eye sight. By 1917, he was living on East 31st Street, working as an artist at 1441 Broadway, possibly making designs the Hartford Textile Company in that building.

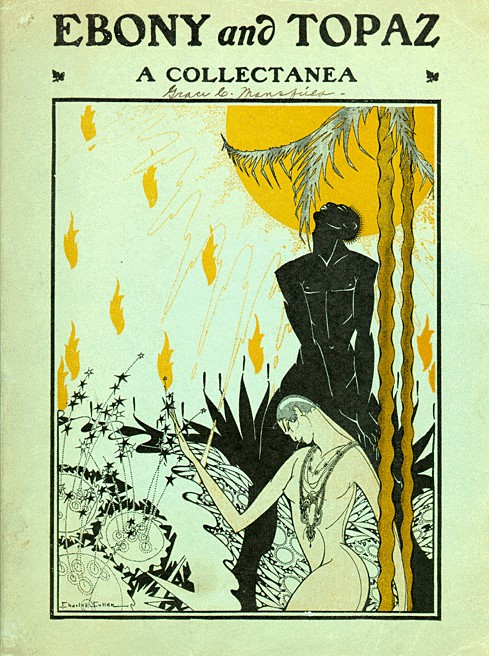

Around this time, Charles Cullen met the African American writer, performer, artist Bruce Nugent (1906-1987), who worked as a bellhop at the Martha Washington Hotel near Charles’ apartment. Bruce was gregarious and openly gay, while Charles was much more conservative with his sexuality (Bruce later called him insipid) but the two hit it off since they were both aspiring painters. It was certainly through Bruce that Charles began to make contact with members of the Harlem Renaissance. They collaborate several times, most notably with Aaron Douglas on the illustrations for Ebony and Topaz, A Collectanea (1927), an anthology of prose and poetry published by Opportunity magazine.

Around this time, Charles Cullen met the African American writer, performer, artist Bruce Nugent (1906-1987), who worked as a bellhop at the Martha Washington Hotel near Charles’ apartment. Bruce was gregarious and openly gay, while Charles was much more conservative with his sexuality (Bruce later called him insipid) but the two hit it off since they were both aspiring painters. It was certainly through Bruce that Charles began to make contact with members of the Harlem Renaissance. They collaborate several times, most notably with Aaron Douglas on the illustrations for Ebony and Topaz, A Collectanea (1927), an anthology of prose and poetry published by Opportunity magazine.

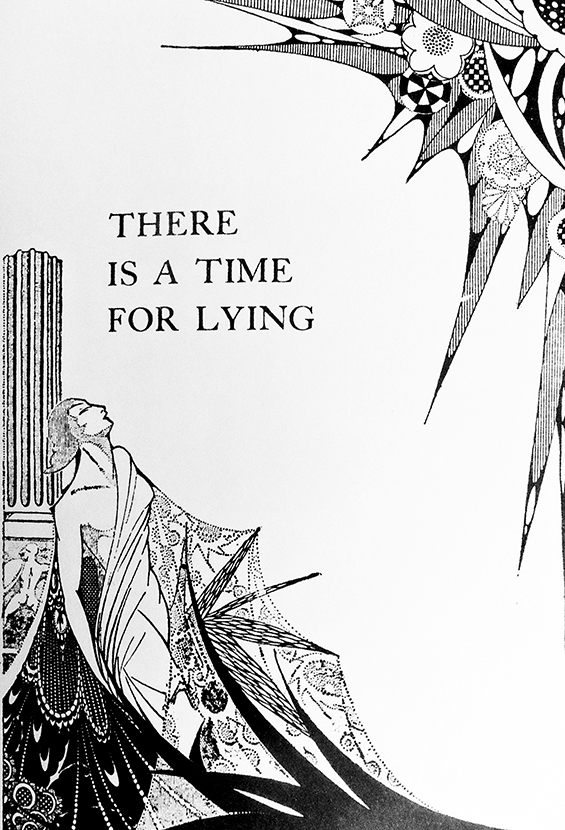

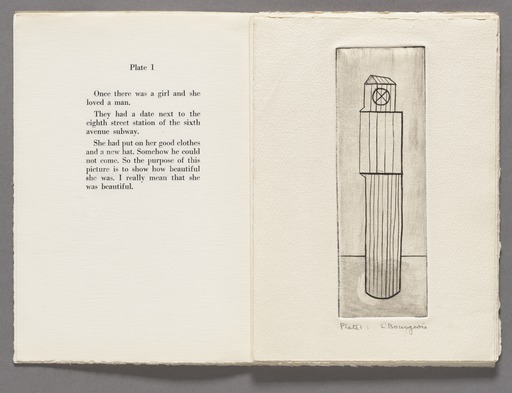

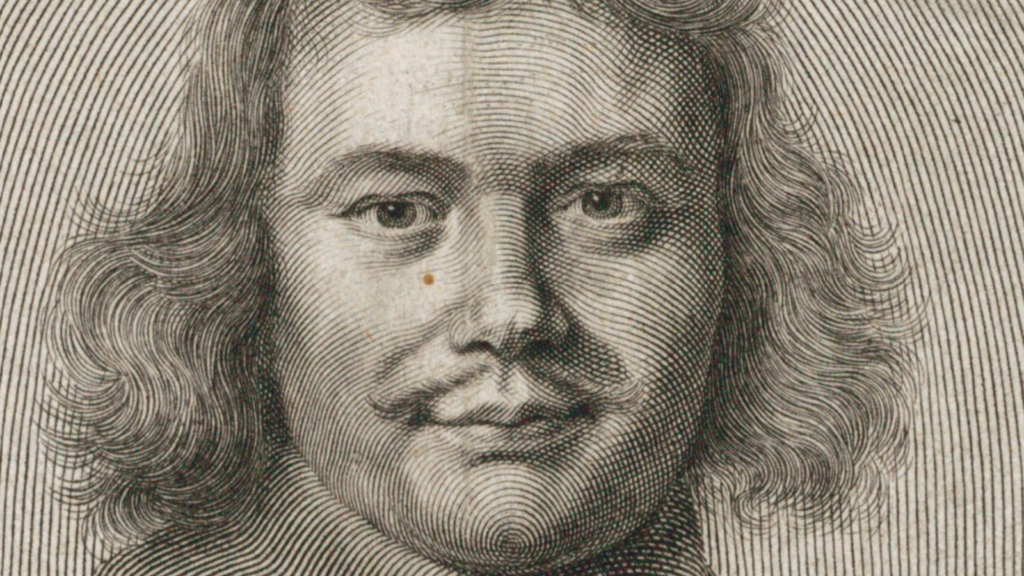

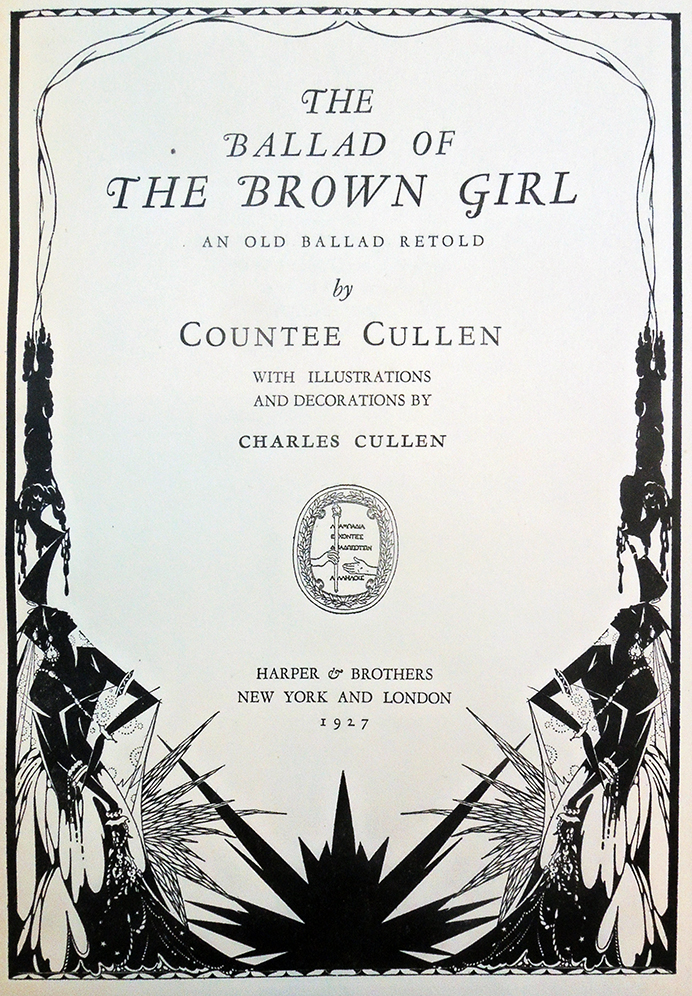

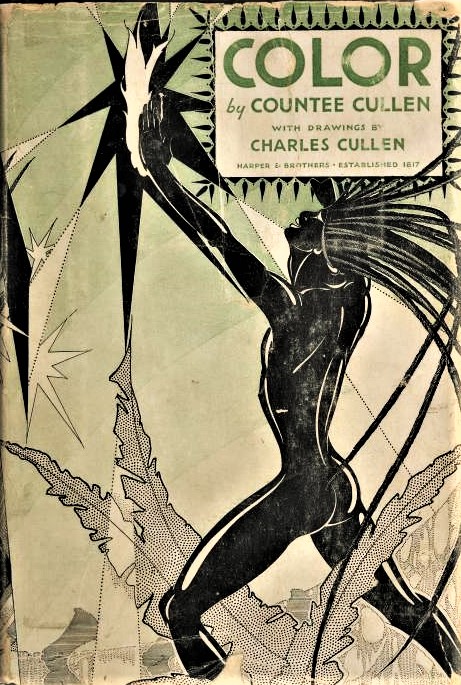

According to Gwendolyn Bennett (Opportunity September 1927), it was Matthew Cullen who gave his son a poetry book by Countee Cullen (1903-1946) entitled Color (1925). Written while still in school, Countee finished his master’s degree at Harvard and then, moved back to New York City.  Charles arranged an introduction to the young Black poet, who strangely had the same family name, and showed him some drawings he had made styled after Aubrey Beardsley’s erotic black and white designs. Enticed, Countee arranged to have Charles illustrate his next book, Copper Sun (1927), followed by The Ballad of the Brown Girl (1927), an illustrated second edition of Color (1928), and The Black Christ and Other Poems (1929).

Charles arranged an introduction to the young Black poet, who strangely had the same family name, and showed him some drawings he had made styled after Aubrey Beardsley’s erotic black and white designs. Enticed, Countee arranged to have Charles illustrate his next book, Copper Sun (1927), followed by The Ballad of the Brown Girl (1927), an illustrated second edition of Color (1928), and The Black Christ and Other Poems (1929).

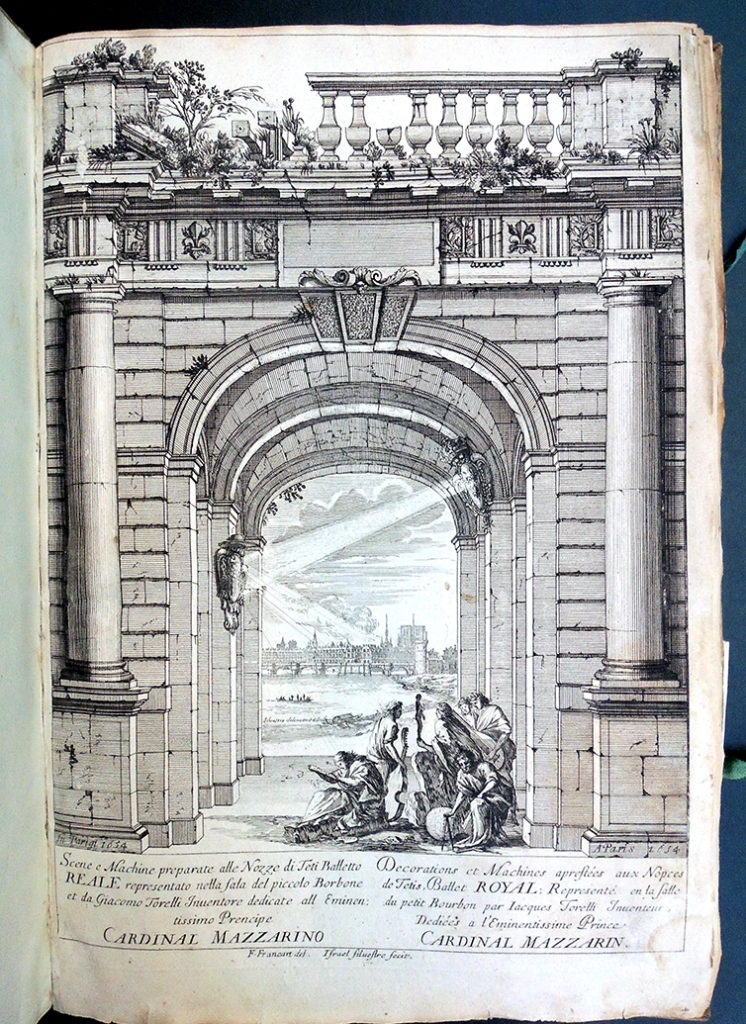

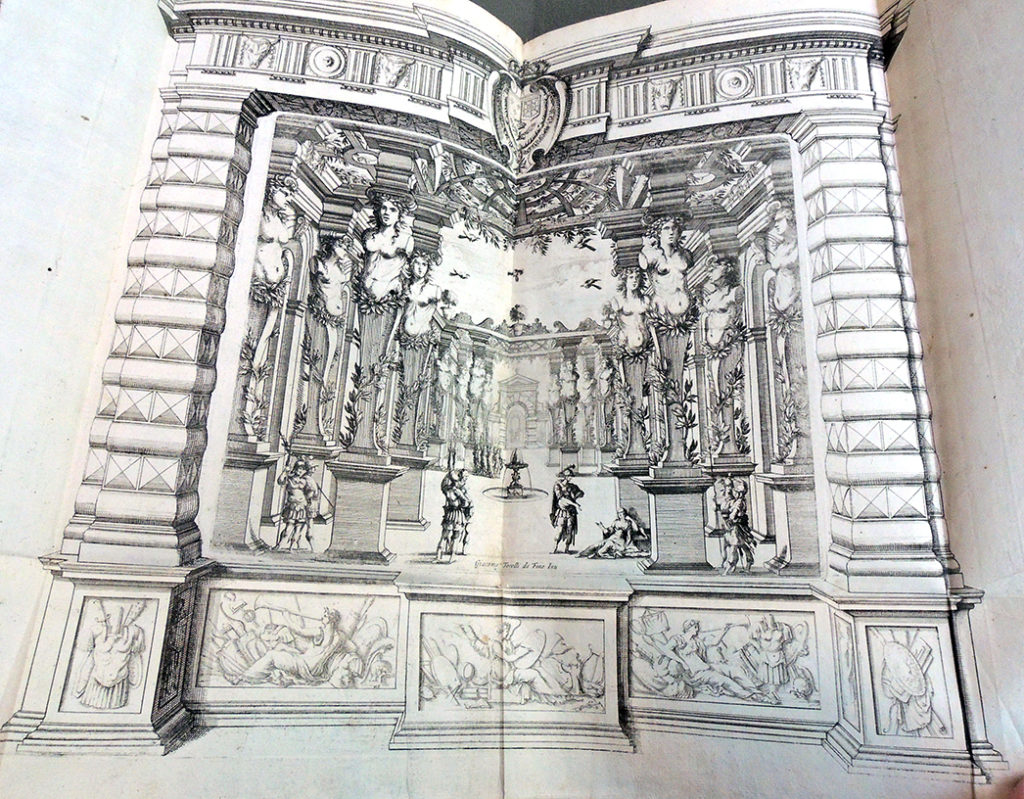

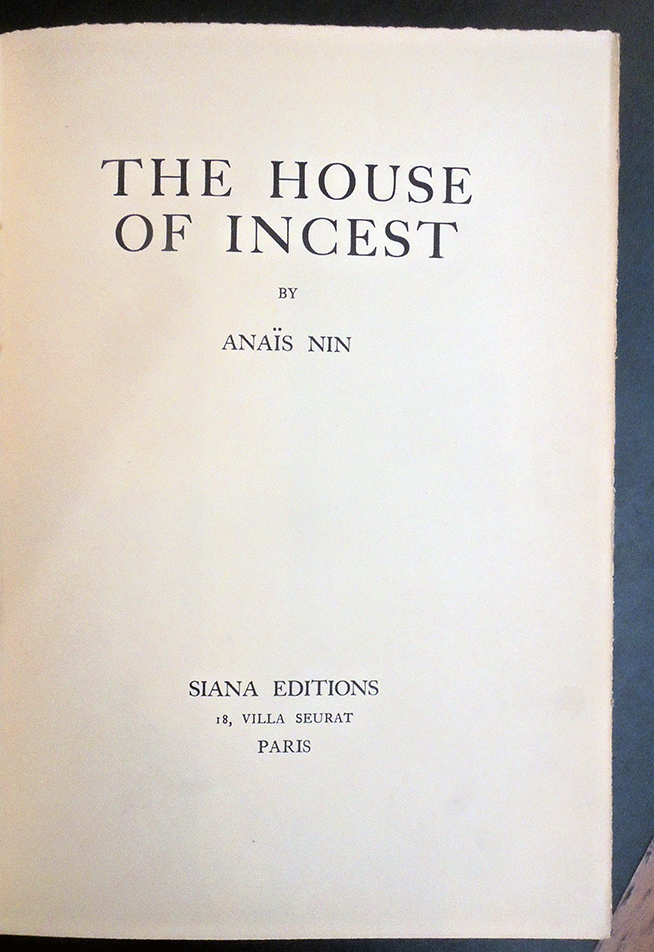

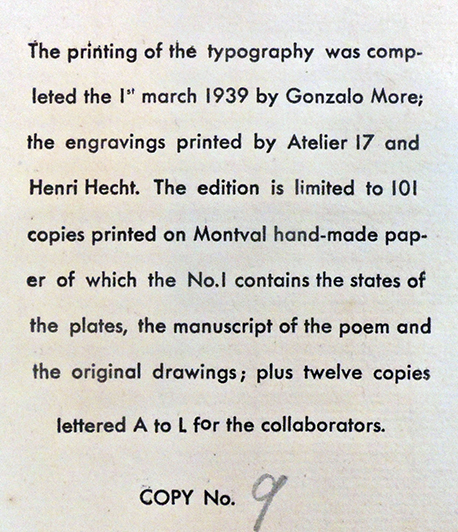

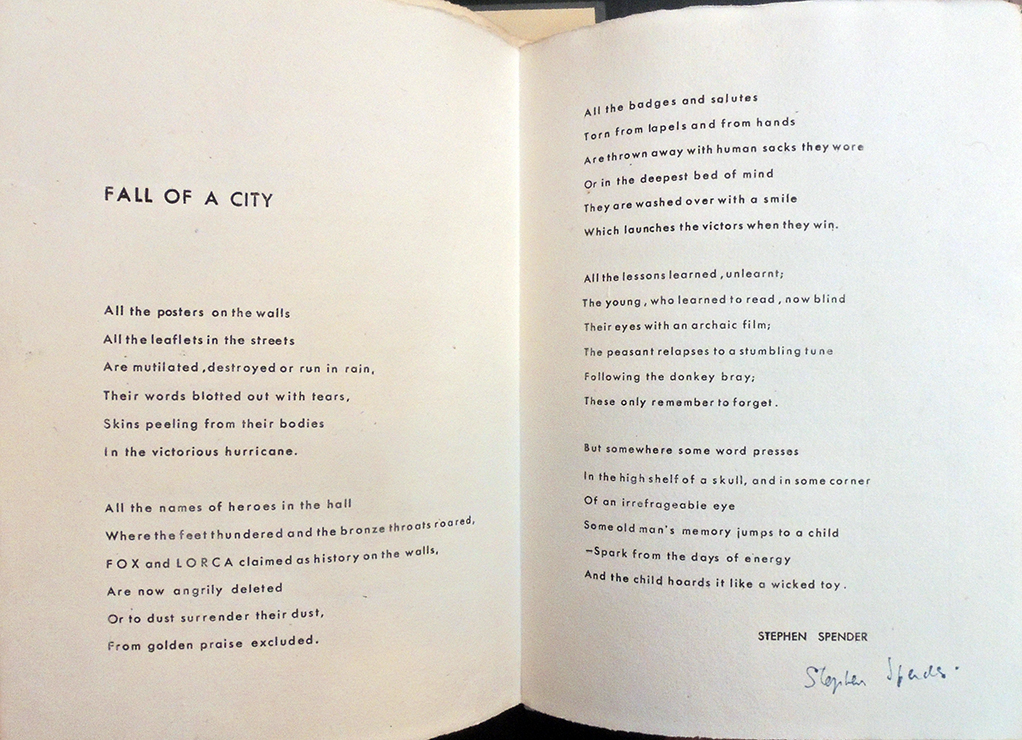

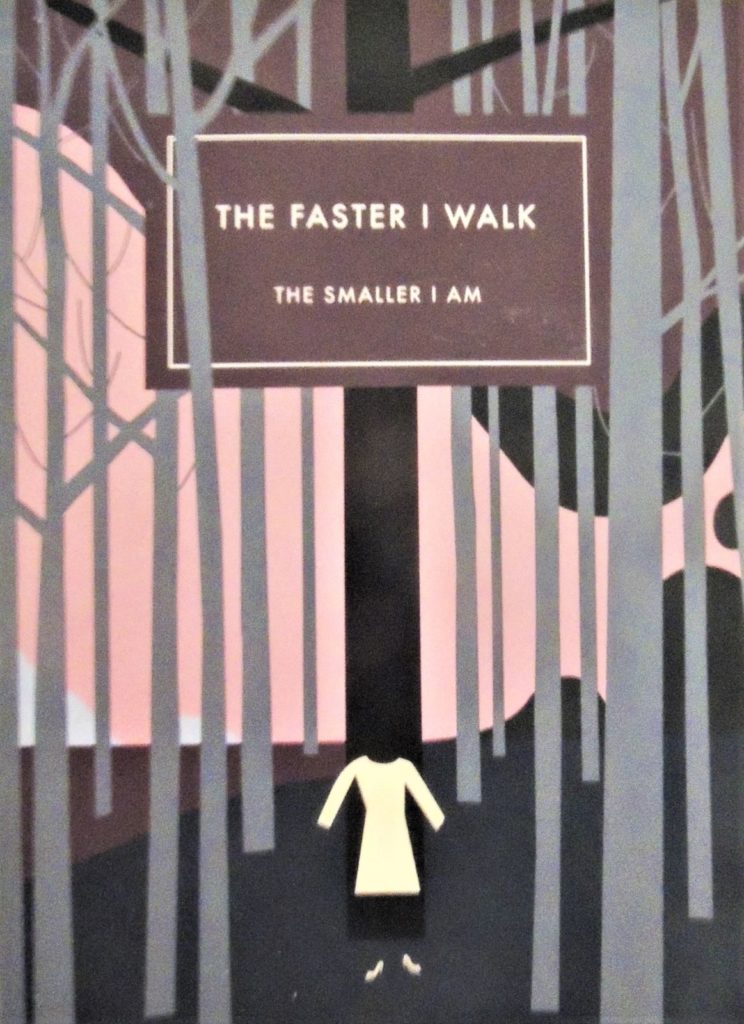

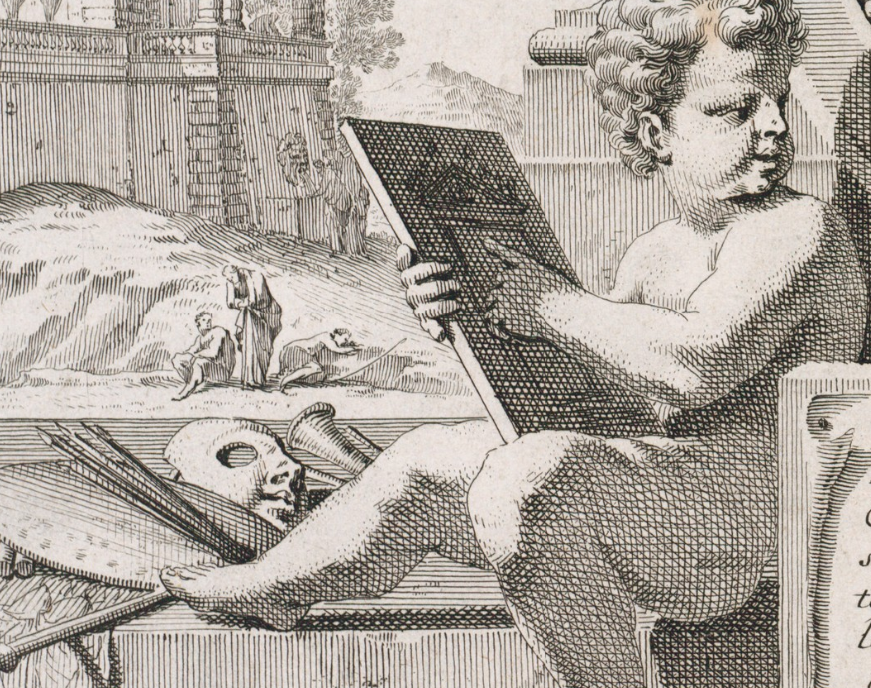

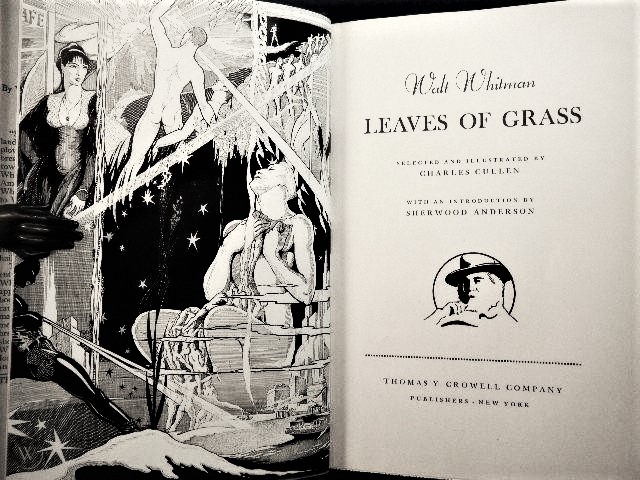

At this point, Charles and Countee end their literary partnership. This may have had something to do with the artist’s next project, privately printed for Rarity Press, which was Dialogues of the Courtesans, an illustrated collection of erotic texts by Lucian of Samosata, with chapters that include “The Pleasure of Being Beaten,” “The Terror of Marriage,” and “The Lesbians,” among others. Another overtly sexual volume appeared in 1933, when Charles selected and illustrated sections of Leaves of Grass by Walt Whitman, with an introduction by Sherwood Anderson. Charles received only one more commission, illustrating Contemporary American Men Poets in 1937 and then work dried up.

Three years later, when Charles filled out the 1940 census form, he had been without work for 156 weeks, living with a young social worker named Torlyn Perstholdt. Little else is known about Charles Cullen’s later years. A small illustrated “Life of Christ” published out of Nashville, Tennessee, must have helped pay the rent. When he died, there was no obituary.